Traces Of Peter Rice E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Lilliput Press is delighted to be reissuing Traces of Peter Rice for the first time in paperback. This book is a collaborative enterprise, British, French and Irish, representing the countries where Peter Rice passed most of his life and the cultures that formed him. These essays and cameos range widely across his career and legacy. Family, friends, scholars and colleagues write about his work, his solutions to intractable problems and his aesthetic sense, seeking to provide an understanding of his works and days. On the books original publication in 2012, Arup Phase 2 in London, the Centre Culturel Irlandais in Paris and Farmleigh Gallery in Dublin developed a series of exhibitions, workshops and conferences dedicated to Peter Rice, for which the essays in this volume provide an indispensable foundation. Peter Rice (1935-1992), a native of Dundalk, was educated at Newbridge College, Queens University, Belfast and Imperial College, London. He joined Ove Arup & Partners in 1956 becoming a director in 1978. Widely regarded as the most distinguished structural engineer of the late twentieth century, his innovations in materials and design hugely advanced the nature of modern architecture. After early work on the Sydney Opera House, he defined the structural elements of buildings like the Centre Pompidou, the Menil Collection museum, Lloyd's of London, the Gare TGV at Roissy, the Pyramide Inversée of the Louvre, Kansai International Airport and the Full-Moon Theatre in the Languedoc. His posthumous An Engineer Imagines (1994) became a byword amongst students and his peers. His influence shaped a new generation of architects and engineers, through his commitment to the integrity of a structure, his refusal of precedent and courage as a designer. He has imprinted les traces de la main on material culture and the built environment with a use of cast steel, ductile iron, stone, glass and ferro-cement. Whether adapting nature's patterns to build flexible structures or transforming our experience of the ecology of light, his public spaces delight and surprise with their sensual mathematics and triumphant integration of the human and the monumental.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 143

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Traces of Peter Rice

.

edited by Kevin Barry

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

Gerberette being lifted into position, Centre Pompidou (Piano & Rogers), Paris 1974. (Bernard Vincent)

Contents

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

1. Memories of Peter –Maurice Rice

2. Peter Rice, engineer –Jack Zunz

CAMEO I: Amanda Levete

3. Renzo Piano in conversation –Kevin Barry & Jennifer Greitschus

4. Peter Rice, lighting engineer –Andy Sedgwick

CAMEO II: Henry Bardsley

5. Richard Rogers in conversation –Jonathan Glancey

6. An engineer imagined –Kevin Barry

CAMEO III: Ed Clark

7. The Peter Rice I knew –Ian Ritchie

8. Working with Peter Rice and Frank Stella –Martin Francis

CAMEO IV: Vivienne Roche

9. Commodious vicus of recirculation –Seán Ó Laoire

CAMEO V: Barbara Campbell-Lange

10. Listening to the idea –Sophie Le Bourva

CAMEO VI: Peter Heppel

CAMEO VII: Hugh Dutton

11. On first looking into Rice’s engineering notebooks –J. Philip O’Kane

NOTES

SELECT PROJECTS

SELECT PUBLICATIONS

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

.

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Peter Rice was inspiring not just because of his brilliance as an analyst, but because he was driven by a commitment to pushing the boundaries of his discipline of structural engineering. Never satisfied with the status quo, he continued to explore the innovative use of materials throughout his life: ‘the search for the authentic character of a material is at the heart of any approach to engineering design’ (An Engineer Imagines, p. 78). Although he described himself as a dreamer with a love of numbers – a label that could safely be used for a lot of engineers – his approach to projects was also collaborative and humanistic.

Rice established his reputation during the late 1970s and through the 1980s at a time when engineers were working with increasingly sophisticated computer technology. Were it not for his untimely death in 1992, he would no doubt have continued to integrate state-of-the-art systems into his own practice. Yet he also had an understanding and love of craftsmanship, whether the work of the Moroccan stonemasons who constructed the dry stone walls of the Full-Moon Theatre at Gourgoubès, in the Languedoc – a project which used no mechanized processes – or the skill of the master plasterer who shaped the sprayed ferro-cement leaves in a single, continuous application for the roof profile of the Menil Collection museum, Houston, or the cast steel of the gerberettes, finished by hand, which were to become the icon of the design for the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Throughout his career Rice valued testing and prototyping, often using handmade models, including for the three aforementioned projects. This element of Peter Rice’s work as well as the collaborative process of evolving a design are explored in the exhibitionTraces of Peter Rice.

The exhibition is complemented by a film and this book, which brings together memories by friends and associates of Peter Rice, who, twenty years after his death, have opportunity to reflect upon his life and work. Rice’s close working relationships with colleagues like Tom Barker at Arup, as well as the extraordinary partnership with his peers in the field of architecture Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, and the later establishment of his own firm Rice Francis Ritchie (RFR) in Paris with Ian Ritchie and Martin Francis, are well documented. Less well known is that he enjoyed working with young graduates whom he gathered around him to cut their teeth on major projects. ‘It was sink or swim, probably like his own experience on the Sydney Opera House’, said Sophie Le Bourva, who first started working with Rice at the age of twenty-three years and who went on to engineer the second Pompidou Centre in Metz designed by Shigeru Ban. ‘But Peter ensured that most of us swam.’

Rice had, in his early career, been on the design team for the Sydney Opera House. He persuaded Jack Zunz, Senior Partner at Arup, to send him to Sydney as site engineer where Jørn Utzon, architect of the Opera House, was to have a lasting impact on the young engineer: ‘I would follow him around site and listen to him reasoning and explaining why he had made certain decisions. The dominant memory was of the importance of detail in determining scale, in deciding the way we see buildings.’

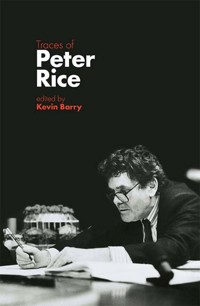

The photograph on the jacket of this book shows Peter Rice at a meeting in 1990 with Japanese architect Yutaka Saito. By this time, Rice was renowned in the world of architecture, with stars of that firmament clamouring for his attention. The model in the background of the photograph was nicknamed ‘the hairy wok’ because of the steel roof sprouting bushes as hair. The project for a studio was relatively modest and small scale (no more than 20m x 10m), but that that did not deter Rice from giving his time to participate in the design session. For him, ideas were key.

Traces of Peter Riceopens in London in November 2012 and tours in May 2013 to Paris and the following autumn to Dublin. Its form and content will respond anew to the character of each venue. Workshops and conferences will be organized in all three cities. This is the last exhibition of the current programme at Arup in London by Phase 2, which presents and produces multi-disciplinary exhibitions and events globally. Since 2008 the London space has been used for the exploration of innovative ideas and cross-disciplinary exchange between the fields of architecture, engineering, art and design.Traces of Peter Riceis a fitting exhibition for the Phase 2 programme since Peter Rice personified its agenda through the way he worked, the boldness of his projects and his passion for life.

The three parts of this project, exhibition, film and book, owe much to Peter Rice’s family: Sylvia, Kieran, Julia, Heidi, Nemone and Nicki, and to his siblings Maurice Rice and Kitty Gibney. I am indebted to them for their generosity and willingness to share memories and personal collections.

The contributors to this book have created a fantastic tribute to Peter Rice. I thank Kevin Barry, who has edited this diverse range of texts so capably, Henry Bardsley, Barbara Campbell-Lange, Ed Clark, Hugh Dutton, Martin Francis, Jonathan Glancey, Peter Heppel, Sophie Le Bourva, Amanda Levete, J. Philip O’Kane, Seán Ó Laoire, Renzo Piano, Ian Ritchie, Vivienne Roche, Richard Rogers, Andy Sedgwick, and Jack Zunz. Thanks also to Antony Farrell and all at The Lilliput Press, Dublin, for pulling out the stops to meet our publishing deadline, and to Niall McCormack for the elegant book design.

The film, which offers an illuminating new portrait of Peter Rice and a valuable record for future studies, is the work of Ben Richardson. Its completion would not have been possible without the assistance of Taghi Amirani, Piers Dennis, Kelsey Eichhorn, Will Fewkes and Chris Wanklyn. Thanks to all who gave their time to be interviewed.

Invaluable to our project was the advice of many of Peter Rice’s past associates: Laurie Abbott, Henry Bardsley, André Brown, Humbert Camerlo, Barbara Campbell-Lange, Mike Davies, Mike Dowd, Hugh Dutton, Martin Francis, Lennart Grut, Shunji Ishida, Peter Morice, Nicolas Prouvé, Ian Ritchie, Yutaka Saito, Alan Stanton, John Stanton, Frank Stella and Jane Wernwick.Traces of Peter Ricealso benefitted from the guidance and help of the following colleagues at Arup: John Batchelor, Tristram Carfrae, Ed Clark, Bruce Danziger, Alistair Guthrie, Mitsuhiro Kanada, Keiko Katsumoto, Sophie Le Bourva, Rory McGowan, Andy Sedgwick and Pauline Shirley as well as that of former Arupians: Tom Barker, Brian Carter, Bob Cather, Bob Emmerson, John Thornton and Jack Zunz.

The exhibition was made possible through the close cooperation and generosity of the following lenders: Humbert, Viviane and Alexandre Camerlo; Mike Dowd; Martin Francis; Fondazione Renzo Piano; Sylvia Rice and Kieran Rice; Ian Ritchie and Frank Stella. Thanks also to Vicki MacGregor, Curator of Exhibitions at Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners, and Jo Murtagh, assistant to Richard Rogers, for enabling access to archive material and liaising on our behalf with key people at the crucial time of planning the exhibition. Rozenn Samper atRFRand Stefania Canta and Chiara Casazza at the Renzo Piano Building Workshop provided excellent support in gathering together visual material.

Producing an exhibition likeTraces of Peter Ricerequires an intense collective effort. I am most grateful to Jeremy Leahy, Toria Richardson, Richard Roberts, Rob Updegraff and Nick Westby, who have been a terrific team to work with on exhibition design, build and installation over the four years of the Phase 2 programme and who have excelled in their work for this show. The beautiful pod, inspired by Peter Rice’s collaboration with Humbert Camerlo on the Full-Moon Theatre, has been designed by Tristan Simmonds. Wolfram Wiedner has provided an inventive and captivating graphic design to weave the elements together. Diana Kovacheva, Ralph Wilson and Eva Xie deserve special thanks for assisting on the project with enthusiasm and resourcefulness. Jane Joyce, Ruby Kitching and Mark Whitby have been meticulous in their research towards creating a digital profile of Peter Rice for an online engineering timeline. I also thank Francesco Anselmo for adapting and reconfiguring the timeline software for the exhibition and for his computer programming for Phase 2 since 2008, and Philip O’Kane for taking on the task of digitizing Peter Rice’s notebooks.Traces of Peter Ricewould not have been possible without the encouragement and continuous support of Martin Ansley-Young, Chris Luebkeman, Andy Sedgwick and David Whittleton at Arup. I thank Philip Dilley, Chairman of Arup Group, under whose auspice Phase 2 was initiated.

This project is a collaboration between Arup, Culture Ireland, the Centre Culturel Irlandais, and the Irish Office of Public Works. I am immensely grateful to Sheila Pratschke, Director of the Centre Culturel Irlandais, to Mary Heffernan of National Historic Properties, to the team at Farmleigh Gallery, and to Kevin Barry, Professor Emeritus at the School of Humanities, National University of Ireland, Galway, whose dedication ensured that our collective endeavour was brought to fruition.

It is thanks to you all that the traces of Peter Rice endure.

Jennifer Greitschus

Head of Exhibitions, Arup

1. Memories of Peter

Maurice Rice

I was born in Dundalk shortly before the Second World War, some three and a half years after Peter. Life in an Irish provincial town was of course restricted during the war years and for some time after, but we were spared the terrible consequences that occurred elsewhere. My memories of this time are fragmentary. Our father was proud of the car that he bought shortly before the war. It sat in the garage on brick piles for many years. Peter and I would sneak in from time to time and pretend to drive it. When finally petrol became available, our father used it regularly to get out of the town and take walks in the countryside. Peter has written inAn Engineer Imaginesabout these excursions to the woods near Ravensdale and the Irish Sea at Gyles Quay. We would spend the time building sand castles and competing on whose could withstand the incoming tide the longest. Driving in rural Ireland had other excitements like threading through flocks of cows or sheep and holding one’s breath as chickens scurried home across the road when a car approached. These trips also allowed us to observe the Irish ability to accommodate all sides. As we passed a rural pub on a holiday, the front doors would be shuttered and closed in accordance with the law, but the car park would be occupied, indicating there were customers who had gone in through the back door.

Peter Rice at fancy dress paradec.1942.(Maurice Rice)

This Irish trait was also very much in evidence during our schooling. Peter and I went to the Irish Christian Brothers School, which put emphasis on discipline and learning to do well in the state examinations. The Marist fathers ran the other nearby school. It had a more relaxed approach with pupils drawn from the sons of the local merchants etc. Peter started school there. However, we were from a family of teachers and our mother was determined that we would have a strict education, since there was no family business to inherit. So when she quizzed young Peter to see what he had learned, she was disturbed and the school was changed. The Christian Brothers went beyond the government’s policy of one class per day of compulsory Gaelic for all schoolchildren and used Gaelic for all subjects, except English. The result was a disconnect between school in Gaelic and daily life in English. The outcome was predictable and the Gaelic revival did not spread beyond a committed minority. Neither Peter nor I developed much enthusiasm for the study of ancient sagas and mournful poems lamenting the sorrowful history of our country.

Thomas ‘Dada’ Quinn with daughters and grandchildren at his home in Inishkeen,1946: Peter Ricefront left, Maurice Ricefront centre, his sister Kitty on ‘Dada’ Quinn’s right; Maureen Rice stands behind her father, her husband James to her left with cigarette.(Maurice Rice)

When the time came for university, our father made the unusual decision, especially for the 1950s, to send Peter to study engineering at the Queen’s University in Belfast. He felt that Belfast, being an industrial city with a tradition in aeronautical and marine engineering, was a more appropriate choice than Dublin. Belfast at that time was a rather dreary place that largely shut down on Sundays in conformance with its dominant Presbyterian culture. Peter, however, was undaunted and had no reservations about entering fully into university life. He joined the rowing club and the university Air Squadron – a programme sponsored by the Royal Air Force to gain access to university undergraduates. When he visited home, he would regale us with stories about his adventures learning to fly in Chipmunk trainers. As the younger brother I was very impressed when he talked about his flying escapades, before being rescued each time by the instructor sitting behind him. As his studies drew to an end, the trainees went to anRAFbase to be exposed to jet fighters etc. However, Peter decided not to pursue a career in theRAFand preferred engineering, much to the relief of our mother. Thinking back, the choice of Queen’s was surely a good one as it exposed Peter to aeronautical engineering and opened him to a wider approach to novel and light structures than was available in standard civil engineering.

Peter Rice, ‘Dada’ Quinn, Aunt Nora, Kitty, Mauricec.1945(Maurice Rice)

Peter and Maurice Rice, Dundalk 1942.(Maurice Rice)

After Peter moved to London and I was studying in Dublin, our paths didn’t cross until I moved to Cambridge in 1960. Shortly thereafter Peter and Sylvia married and I was an inexperienced best man. But the wedding went off well. It was not a big affair, in keeping with the modest salaries paid to engineers. They moved into a flat in Notting Hill Gate, which at that time was starting to be gentrified. Peter was excited to be working with Ronald Jenkins who he said was the best at Arup. In the years that followed we lived far apart, he and his family moved to Sydney and I to the United States.

Our next overlap was in theUSA. After leaving Sydney he spent a year decompressing at Cornell University from the stress of working on the Sydney Opera House. I was living not too far away in New Jersey, newly married. I remember well a weekend together in Ithaca. It was winter and very cold in upstate New York. Peter and Sylvia had three young children by then and were living in a large old wooden house. Helen and I were overwhelmed by the activity level of young children and were taken aback when Peter took all three out for a walk in the bitter cold. Later when we had our own kids, we understood. Peter had by then developed a passion for gourmet living, or more accurately a combination of gourmet and gourmand.

In the years that followed we would meet mostly in London when I was passing through. Many times we went down to Berwick St John, a small village in Wiltshire where Peter and Sylvia had a cottage. Peter always tried to arrange his crowded schedule in London, Paris and Genoa so as to spend his weekends there. He loved to go running and kept very fit. That was the place where he could turn off, relax and hone his cooking skills. We sometimes talked about engineering and physics, my profession, and found that both of us were stronger on ideas than on the technical calculations.

Peter and Sylvia on their wedding day, London 1961.(Maurice Rice)

Peter was always so healthy and full of life that the brain tumour came as a great shock to all and especially to him. The combination of a deadly prognosis and great restrictions on his sight were hard blows, at a time when he was in his fifties and his professional life was flourishing. But he did not withdraw and feel bitter about his cruel fate. He set about making the most of his remaining time. He produced the bookAn Engineer Imagines