Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

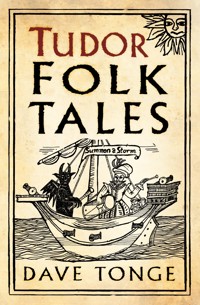

In Tudor times the 'common sort' were no different from us, laughing together, mocking each other and sharing bawdy tales in tavern yards, marketplaces and anywhere else that people came together. These stories were later collected in the cheap print of the period, and professional storyteller Dave Tonge has sought them out to assemble here. Within these pages hide smooth-talking tricksters, lusty knaves, wayward youths and stories of the eternal struggle to wear the breeches in the family, for a sometimes coarse but often comic telling of the everyday ups and downs in Tudor life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 301

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Kim Voisey,whose wonderful illustrations adorn my book

First published 2015

This paperback edition published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Dave Tonge, 2015, 2019

The right of Dave Tonge to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 6673 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

Chapter I: The Struggle for the Breeches

Of the Mute Wife

Of the Contrary Wife

Of the Gentlewoman Who Had the Last Word

Of the Knight and the Widow

Chapter II: The World Turned Upside Down 1‘The Wit and Wisdom of Women’

Of the Goodwife of Orléans

Of He Who Painted a Lamb

Of the Hunchbacks Three and One Other

Of the Partridges and the Priest

Of the Lady Prioress and the Three Lusty Knaves

Of the Poor Gentleman and His Hawk

Chapter III: The World Turned Upside Down 2‘Masterless Youth’

Of the Brother Who Found a Chest

Of the Father Who Bequeathed a Gallows

Of the Friar, the Boy and His Stepmother

Of the Best Forgotten

Chapter IV: The World Turned Upside Down 3‘Poor Men Will Speak One Day’

Of Adam Bell, Clim of the Clough and William of Cloudesley

Of the King and the Radish

Of the Village of Fools

Of the Village Where Insults Flowed Freely

Chapter V: A Caveat for Common Cursitors

Of the Miller Who Stole the Nuts

Of Howleglas and the Ceiling Cunningly Painted

Of Howleglas and the Village Without Sin

Of Howleglas and the Miracle Cure

Of Judgements Well Made

Chapter VI: The Many-Headed Monster

Of the Yeoman’s Wife

Of the Man Who Paid With Naught

Of He Who Said Ne’er a Penny

Chapter VII: The Commotion Time

Of the Friar and the Butcher

Of the Friars and the Merchant

Of the Last Will and Testament

Of Friar Bacon’s Choice

Chapter VIII: Fact or Fiction, Truth or Lies?

Of Drake the Wizard

Of Merry Master Skelton

Of the Reward for Lying

Notes

Glossary

Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

ong before I ever became a storyteller I was a historian, burrowing into sixteenth-century court records, researching the relationships between men and women and looking at how they were dealt with in courts and how they interacted with each other. It was a revelation to me that we could know so much about our ancestors and I soon realised that Tudor people were not that different from us. They reacted to crises and related to each other much as we still do today. Their problems were different, but they were not.

When I became a storyteller, I found that there was a wealth of sixteenth-century ‘chap books’ and other cheap print available to me. From moral works to ‘gest’ books, as soon as I read the tales I realised that their themes and characters reflected those I had already found in my historical research. Yet again they show us that Tudor people were not that different from us!

More importantly, both the records and stories show us something of the reality of Tudor life, not the idealised version as seen in Acts of State and sermons of the time. Evidence often used to paint a picture of an oppressive society, where everyone knew their place. But that is an oversimplification of life long ago and although it was a patriarchal and hierarchical society, these were complicated times.

There were conflicting ideas and attitudes that can be seen in the records and stories I have included in this book. Long ago publishers were desperate to sell their wares to as big an audience as possible and included titles that would appeal to all, which means that for every story mocking a certain group there is also a reply, redeeming them.

The stories were adapted from older medieval sources such as the Decameron and Heptameron and were also taken directly from oral culture by printers who were always looking for new material to feed a growing audience for cheap print. Even though literacy levels were low, the stories could be read out in tavern yards and other public places, thus returning to the oral culture from whence they came.

Some of the medieval material appealed to people of higher status, focusing as it did on nobility, chivalry and adventure, but the old stories had little to offer the lower orders who preferred comic and often bawdy tales that still reflected something of their dreams, fears and desires. That said, cheap print was just that and some of the humour was coarse and unsubtle, while the ideas and attitudes within do not always sit well with modern tastes. They were, however, a welcome release from the tensions created by the conflict between idealised expectations and the reality of Tudor life, but more of that below.

As for this book, it is a work of two halves. First, the historical introductions, with a variety of records including many from the consistory courts, the church courts held in Norwich and also the city’s mayor’s court (all records are from the city sessions unless otherwise cited). Tudor Norwich was second only to London in size and wealth and so the examples from there are representative of any major town or city of the time. In addition, the court regulated many aspects of daily life, from what a person wore to the price of grain, family life, sanitary practices, moral lapses and even entertainment; thus it gives us a wonderful insight into Tudor society. This is me writing with my academic head on, although when it comes to the records, some of the spelling and punctuation has been changed for the ease of the modern reader.

The second half consists of the stories themselves and it is here that I write as the storyteller. Many of the tales were printed as short anecdotes in the sixteenth century, for the ease of the printer as well as to make them accessible to a semi-literate audience. Once storytellers got their hands on them, though, it was a different matter. Then, as now, storytellers ‘grew new corn from old fields’, padding stories out with their own experiences and adapting them to suit their audience. That’s exactly what I do as a teller of tales and what I have tried to do with the stories below. Because many of the tales were drawn from oral culture and told aloud in Tudor times, I have attempted to give a feel of the telling in my versions.

I have also amalgamated some of the smaller stories into larger ones and created new titles where necessary in this, my book of two halves. Two halves, yes, but they come together to show something of the ideas, attitudes and beliefs of our Tudor ancestors.

Thanks to Helen James and Debbie Handford for amending my terrible grammar. Also to Colin Howey for the use of his Norwich records and to Stewart Alexander for introducing me to the wonder of storytelling!

Dave Tonge, 2019

CHAPTER I

THE STRUGGLE FOR THE BREECHES

OF THE MUTE WIFE

n 1571, the author of A Homily Against Disobedience and Willful Rebellion denounced all kinds of rebellion including in families and households, stating that ‘the wife should be obedient unto her husband’.1 A few years earlier in 1568 the courtier Edmund Tilney had written: ‘It is the office of the husband to deal and bargain with men, of the wife to make and meddle with no man.’2

Both these examples present an idealised image of women long ago, but statements such as these did not reflect the reality for many Tudor women who clearly took no notice of such advice; women such as Mary Wyer, the wife of Edmund, who was ordered to be ‘sent to Bridewell and from there to the duck stool and there to be ducked three several times for scolding with her neighbours and other outrageous behaviour’. Also Alice Cocker, who was to be ‘set in the cuckingstool as a common scold and brawler and a women of disquiet among her neighbours for that she did beat Ellen Dingle and Joanne Tymouth’. Both women were of course punished, but not for their scolding ways, rather for the antisocial behaviour that accompanied it.

Tudor society was a patriarchal society, but that does not mean that women did not have a voice, a fact that some men used to their advantage. As, for example, when John Elwyn was sent to serve a warrant on Henry Symonds, who ‘did stay back and animate his wife who tore the warrant up and with lewd and unseemly speeches said, a turd in thy teeth, I thought the Mayor had more wit’.

Symonds was all too willing to exploit a woman’s subordinate position within the household and clearly many Tudor women were happy to speak their minds, a reality that’s also reflected in stories from the time. Stories like the one below, a comic tale that deals with the troubles between husband and wife, or what was often termed ‘the struggle for the breeches’ …

In the fair and fine city of Norwich where I come from there lived a rich merchant, a man who made his coin by buying and selling wool. A thriving trade in the time of King Henry and his children and the merchant was skilled at his profession. So crafty was he that he had many great chests of gold in his counting house, but this rich merchant of Norwich was no miser. He loved to spend the chinks and so he bought a fair and fine house in the shadow of Norwich Castle. In that house he had fair and fine tapestries upon the wall and many not so fair and fine servants to do his bidding. The rich merchant wore fair and fine clothes, certainly much finer than any of you reading this story today! And that rich merchant also had himself a fair and fine young wife called Elizabeth.

Ahhh, Elizabeth! She was beautiful. Some said she was the most beautiful woman in the whole of Norwich, while others said no, she was the most beautiful woman in the whole of Norfolk, ‘and you can’t get fairer or finer than that!’ The merchant, however, knew better, for he felt certain that she was the most beautiful young woman in the whole of Merry Old England. Perhaps he was right, for her hair was the colour of the brightest summer sun on the brightest of summer days. Her skin was as soft as duck down and as smooth as marble. Her lips were redder than the reddest ruby ever plucked from the earth, or the reddest rose ever plucked from the bush, and she smelt just as sweet.

Alas though, there was a problem with Elizabeth and the problem was this … she was mute. Never had a word passed her lips, which bothered the merchant greatly and he longed to hear her speak. He felt certain that if his fair and fine young wife could speak, then surely her voice would also be fair and fine. He felt certain that if Elizabeth could talk, her voice would match the birds singing in the trees, or even the very angels singing to the glory of God in heaven above. And so it was that he was sad that she had never uttered a word.

He was not, however, sad all of the time, for the merchant was a haunter of alehouses and loved a strong pot of ale when the working day was done. Each and every night you would find him in the alehouse with his many friends, but on this evening he arrived at the alehouse early and there was no one else about except for the alehouse keeper and a stranger to the city. A very strange stranger indeed, for when he thought about it later, the merchant could remember no detail of the man, save only that he wore a dark cloak and a dark hood which covered his face. And so they sat, the rich merchant on one side of a table, the stranger on the other and now they caught each other’s gaze. The stranger glimpsed the sadness just in the corner of the merchant’s eye and he asked him what ailed him, what had brought the merchant so low? The merchant said, ‘I have the most beautiful wife in the whole of Merry Old England. Her hair is the colour of the brightest summer sun on the brightest of summer days. Her skin is as soft as duck down and as smooth as marble. Her lips are redder than the reddest ruby ever plucked from the earth, or the reddest rose ever plucked from the bush, and she smells just as sweet. But,’ said the merchant, ‘she is mute, she cannot speak and I wish that she could talk, for I feel certain that if she could talk her voice would match the birds singing in the trees, or the very angels singing to the glory of God in heaven above. That,’ said the merchant, ‘is why I am sad.’

Well, the hooded stranger began to laugh. ‘Is that your problem?’ asked he. ‘Why, that’s no problem at all.’ And now the stranger reached into his pouch and pulled out a small bone, which looked like a human bone, perhaps from a finger or even a toe, but the merchant thought it better not to ask. ‘Take this bone home and bind it with a lock of your own hair,’ said the stranger, ‘then place it beneath your sleeping wife’s tongue for one hour before midnight, till exactly one hour after midnight. No more, no less!’

The merchant was so desperate to hear his young wife speak that he followed the stranger’s instructions to the letter. At one of the clock in the morning he plucked the bone from beneath his sleeping wife’s tongue. He kissed her gently and tried to settle down to sleep. But this night sleep would not find him, for he was desperate to know if his wife had won her voice. He was desperate to know if that voice was finer than the birds singing in the trees, or the very angels singing to the glory of God in heaven above. And so it was he sat up in bed and kissed his wife a second time upon the cheek. ‘Wake, Elizabeth,’ he whispered. ‘Rouse yourself, Elizabeth, and talk to me.’ Well, slowly, oh so very slowly, the merchant’s young wife began to awaken in a most fair and fine fashion. Her eyelids fluttered in a fair and fine fashion. She sat up in bed and she stretched and yawned in a very fair and fine fashion. Slowly, oh so very slowly, Elizabeth turned to her husband and she spoke. It was the first time that the beautiful young woman had ever, ever spoken.

‘WHAT DO YOU THINK YOU ARE DOING WAKING ME UP AT THIS TIME?’ she screeched. And now she chided and scolded her husband, calling him fool and dullard and other outrageous oaths too lewd, earthy and Tudor to mention here. Her fair and fine mouth had become a dunghill of filthiness! She harangued her husband for a full hour or more, until he could bear it no longer. He rose early and went to his place of business.

But the merchant did return home that night, for he felt certain that given time both Elizabeth and her new tongue would settle some. Alas, though, as the days turned into weeks and the weeks turned into months his fair and fine young wife developed an evil disposition. ‘WHAT DO YOU THINK YOU ARE DOING STAYING OUT ALL NIGHT?’ she screamed, ‘YOU THINK MORE OF YOUR FRIENDS THAN YOU DO OF ME.’ Then there was her tongue – he had never seen a tongue as busy as hers and the merchant took to likening Elizabeth’s tongue to a sharp blade, for every time she scolded him it cut that man to the bone! Oh how he wished he could sheath that knife. Oh how he wished that he could shut up his scolding wife.

Now if she had been the wife of a poor man she would have been ducked in the River Wensum, three times at the least, but as the wife of a rich man she was not. And so it was in desperation the rich merchant went in search of the hooded stranger and when at last he found him drinking in a tippling house of low credit, he fell to his knees and begged the stranger, ‘Please, please, PLEASE, take back my scolding wife’s voice!’ But the stranger shook his head and said he could not. He stood up and throwing off his hood he spoke once more. ‘Know this, rich merchant of Norwich. I am not really a man, for I am a demon from hell. And like any demon from down below I can work many wondrous spells including giving the gift of speech. But know this, rich merchant,’ said the demon, ‘neither I, nor any demon from hell, why not even the very Devil himself, can shut a woman up once she has started!’

OF THE CONTRARY WIFE

he Tudor family was supposed to function as a miniature state with the husband at its head, but a husband’s power over his wife was not without limits. He could chastise her but excessive violence, as with other forms of abuse or neglect, was not sanctioned by the state and both violent and wayward husbands were punished. Robert Fellingham was set in the stocks for ‘beating and misusing his wife’ while the Tudor writer Edmund Tilney advised men like Fellingham against violence, saying that during an argument the husband ‘must show his wisdom. Either turning it to sport, dissembling the cause or answering not at all.’3

There were limits to how and when a man could sanction his wife and for some men this was a cause of confusion and concern, not least because Tudor treatises on marriage could be ambiguous, often containing conflicting advice. The courtier Edmund Tilney, for example, stated that women should ‘make and meddle with no man’, but goes on to say that it was a woman’s duty to ‘govern her household’.4 It was a role that could bring women into conflict with men and even the authorities, as in 1532 when twelve Norwich women were ordered to be whipped at the cart’s tail for the ‘selling of divers men’s corn against their wills and the setting of prices thereof … contrary to such prices as the mayor has set’. This was seen as a serious crime, hence the harsh punishment, although in this case the whipping seems to have been commuted to a small fine instead. Was it recognition of the poor harvest and subsequent rise in the price of bread that year, but also perhaps of the ambiguous nature of female authority within Tudor society? Maybe it was, but it was not an authority that found much sympathy in stories of the time …

There was once a woman who chose to ignore the foolish prattlings of men who talked too much but never listened. As far as she was concerned it was her job to talk too much and never to listen to anything a man said to her, and she had grown skilled at her craft. The woman argued constantly with her husband and never before or since has there been such a contrary and quarrelsome a wife as she! From morning till night she opposed her husband in all things and she always had to have the last word. He had no choice in the matter, for more than once she had combed his hair with a three-legged stool! If her husband said it was light, she would say it was dark; if her husband said it was sweet, she would say it was sour; if her husband said it was thither, then she would say it was yon!

Well, one early morning, her husband rose from their bed and threw open the shutters to reveal a bright summer’s day. The sky was blue, the sun shone and the bees buzzed busily about their business. The man breathed deep, stretched long and yawned loudly while scratching those places that all men go to first thing and then he spoke. ‘It’s a fair day for a walk, wife,’ he said, ‘and perhaps a picnic by the river?’ But his wife sneered at her husband, calling him ‘fool’ and ‘dullard’, and she replied, ‘The day is clearly foul, for there is rain in those clouds, far better to stay in our bed.’ ‘But wife,’ said her husband, ‘the day is fair.’ His wife replied, ‘The day is foul.’ And so it was they fell to arguing … ‘Fair!’ ‘Foul!’ ‘Fair!’ ‘Foul!’ ‘Fair!’ ‘Foul!’ ‘Fair!’ Until at last her husband gave way to his wife and, as always happened, he let her have the very last word. ‘The day is foul!’ said she, triumphantly.

Nevertheless there was work to be done and now her husband suggested that they walk by the river, so that they might see how their crops were faring in the nearby field. ‘If you come along,’ said the husband to his wife, ‘then it would be the chance you were looking for to wear the new blue dress I bought you at the last spring fair.’ But his wife sneered at her husband, calling him ‘blockhead and dunce’, and she said, ‘The dress you bought me last spring is green, not blue.’ ‘But wife,’ said her husband, ‘the dress is not green. It is as blue as the sky on this fair, I mean foul, day!’ His wife replied that the dress was green. And so it was they fell to arguing once more … ‘Blue!’ ‘Green!’ ‘Blue!’ ‘Green!’ ‘Blue!’ ‘Green!’ ‘Blue!’ Until at last her husband gave way to his wife and as always happened, he let her have the very last word. ‘The dress is green!’ said she, triumphantly.

The argument being settled they went out for a walk, the wife wearing the blue, I mean green, or was it blue, dress. As they walked by the river they talked of many things and argued about even more until they came to the large fields where their neighbours were already hard at work harvesting their rye. And the husband, seeing that the grain had ripened, suggested that they too set to work cutting their crops. ‘Wait here but a while, wife,’ said her husband, ‘while I run home and fetch us two well-sharpened sickles to cut our rye.’ But his wife sneered at her husband, calling him ‘clot-brain’ and ‘oaf’, and she said, ‘You can’t cut the crops with a sickle, husband, for everyone knows that scissors are best!’ ‘But wife,’ said her husband, ‘you cannot use scissors to harvest your crops, for it would take weeks, if not months. The wind, rain and frosts would come and the rye would be ruined!’ His wife replied defiantly, ‘You definitely use scissors, not sickles, to cut the crops.’ And so it was they fell to arguing again that day … ‘Sickle!’ ‘Scissors!’ ‘Sickle!’ ‘Scissors!’ ‘Sickle!’ ‘Scissors!’ ‘Sickle!’

But this time the dispute continued, for this time the husband could not give way to his wife. If he let her have the last word then he would have to cut the crops with scissors and that would take weeks, if not months. The wind, rain and frosts would come and the rye would be ruined! The husband turned his back upon his wife, ignoring her as he walked home along the river to fetch two sickles. But his wife followed close behind her husband unwilling to let him win the day. She skipped about him and whispered loudly in his ear, ‘Scissors, scissors, SCISSORS!’ until at last her husband could bear it no longer. He turned and pushed his wife into the river where she thrashed and splashed, for having been told by her husband that she should learn to swim, she had decided against it. She gurgled and gasped, but still she called out, ‘Scissors, scissors, scissoooors,’ as she sank slowly beneath the water. The woman sank and her husband smiled as he thought to himself, ‘At last I shall have the last word,’ and he called out, ‘SICKLE!’

His triumph was short lived, however, for out of the water rose his wife’s clenched fist. Before his eyes the fist unfurled to reveal two fingers. Two fingers that cut the air as they sank slowly back into the murky depths. And so it was, even in death the defiant women had the last word!

But that is not quite the last word from me, for the story did not end there. You should know that the arguing woman was even more contentious in death and as I heard tell, the wilful woman’s body floated upstream against the current. Even the river could not get the better of the contrary wife!

OF THE GENTLEWOMAN WHO HAD THE LAST WORD

omen spoke their mind long ago and regularly slandered men as well as other women. We know this because they often appear in slander cases before the consistory courts – which, due to the nature of the slanders, were often referred to as the ‘bawdy courts’ – long ago. Thus, Margaret Cock appeared for having slandered Lionel Wade, saying that he was an, ‘old whoremasterly knave and japed Ann Kettle’. Ann Elcocks accused Wesson’s wife of ‘being caught upon the knee of a beer brewer with her clothes up’. Elcocks also said that Wesson was ‘a wittol who received a barrel of beer for the use of his wife’.

Such extreme examples of slander were not just the preserve of the church courts; secular tribunals, such as the Norwich mayor’s court, also dealt with cases, especially when members of the city elite were slandered: Margaret Caly was sent to the Bridewell because ‘on Witson Tuesday last she did revile and miscall Christopher Giles and often times clapped her hand upon her backside and bade him kiss her there’.

The women above were punished for their insults, and while it might be argued that this is further evidence of patriarchal oppression, it is equally true that no matter how harsh the penalties, it did not serve to deter them. They continued speaking their minds, slinging insults in the marketplace, in the alehouse and even in stories like this one. However, unlike the gentleman in this tale, most men knew better than to argue with women, preferring instead to heed the words of Will Shakespeare in The Comedy of Errors, where he reminds us all that ‘there’s many a man has more hair than wit’.5 …

There was once a young gentleman who fancied his wit was equal to that of Friar Bacon – a man whose renown was once so great that there are many tales told about him, one of which resides in the pages of this book. He was a much wiser man than the young gentle fellow who in truth was a coxcomb, not so much a man, but a youth who was conceited in character and vain besides!

Such were his failings that he failed to see them himself and he pranced about town like a peacock among his peahens, displaying his vanity for all to see and seeking to impress any young woman he met, although in time he met his match. For one day while drinking in a low tippling house that was frequented by many a gallant such as he, the gentleman fell to talking with a merry maid who saw beyond his fine feathers and preening ways. She looked upon his boyish beard, for although it was fairly full upon his top lip, it was but thin and wispy upon his chin. ‘Why sir,’ said she to the foppish fellow, ‘you have a beard above, but none beneath.’

The gentleman liked not her words and sought to return them twofold. ‘Why Mistress,’ he replied, ‘you have a beard beneath, but none above.’ And he laughed at the quality of his jest.

But his wit was no match for that of the merry maid who made answer to his joke. ‘Well, sir,’ said she, ‘if that is so, then we should set one beard against the other!’ Such was her answer that I doubt that even the great Elizabethan playwright or even Friar Bacon could have replied, let alone a conceited coxcomb. The young gentleman was so shamefaced, his feathers so ruffled, that he said not one more word, but went instead to seek another peahen less merry and learned than she.

OF THE KNIGHT AND THE WIDOW

or the final story in this chapter I offer you a tale adapted in Tudor times from one of Aesop’s fables. The story is of a widow, for many a young husband long ago died from war, dearth and disease, meaning that many women remarried. Although for some, like the Norwich merchant and mayor Thomas Sotherton, this was a cause for concern. When he died he left about eight thousand pounds, much of it to his wife as long as she was mindful ‘of the mutual long love continued between us’, and that she continue to ‘have an especial care for the good of our children … hoping that no second love shall cause her to remove the most earnest promised love vowed and protested, as well as to me in private, as in the presence of some of our friends’.6 In other words he didn’t want his money being diverted away from his own family!

It is likely that Sotherton’s wife didn’t remarry and some women seem to have been happy to remain widows and run their late husband’s businesses, either alone or with the help of family. That said, many did remarry to protect themselves in later life for it was not easy to be a woman alone in Tudor times. Perhaps that’s why Abry Woolbred was whipped at the post ‘for clothing herself in man’s apparel and offering to go forth with the soldiers’. Her husband, Robert Woolbred, a weaver, had been caught drinking late at night, pressed into the army and sent to fight the Spanish. Was it simply a case that Abry could not manage the household and business without him or could it be an example of true love, that she just couldn’t imagine life without her Robert?

Whatever the case you only have to read Shakespeare to know that it was not uncommon for women to disguise themselves as men. And in the ballad Long Meg of Westminster (1583) the heroine is presented as a strong woman who went to war disguised as a soldier and was eventually rewarded with a pension for life. But this ballad also reflects the ambiguity and unstable nature of women’s position in Tudor society, for Meg eventually marries, promising her husband that she will never return his blows. She goes from being a strong independent woman to a submissive idealised image of womanhood.7 The same ambiguity is reflected in this story, about a strong woman who desires another husband …

Once long ago there lived an alewife, an old woman who divided her time between selling ale and searching for her next husband. She collected husbands as other women collect pins, pots and potions from passing pedlars. The alewife had had more husbands than there were days in the week, but fewer than there were fingers and thumbs on both her hands, although whether it were eight or nine, not even she could remember! All of them had felt the sharp end of her tongue and all of them had felt the cold bony fingers of Death gripping hard upon their shoulders. In time he had come to claim them all and in truth most were happy to go. Her last husband had died just this very week and she was already searching for his replacement, a new man to take his place.

Well, it was on the very day that the alewife’s last husband had died that a notorious rogue was hanged. He had been a thief and murderer of many years’ standing, a man so skilled at his loathsome trade that his body was to be left hanging to rot, to serve as a warning to all other vicious vagrants who passed by. It was left to hang upon the gallows as a message to all who sought to steal and kill, but such was the notoriety of the hanged man that the lord of this place ordered a young knight to guard the corpse. He was to stand watch at the crossroads night and day to protect the body from any who sought to attack it or to steal it away, for who knows what grim purpose.

The young knight was new to his lord’s service. He wanted to please the great man and so followed his orders faithfully. For three days and two nights the young knight never left his post, eating where he stood, napping only briefly against the gallows and using a nearby bush whenever nature called. By the third night, however, the young man grew weary of his post; he was tired and lonely, with only the crows for company. But the crows said little, for they were too busy pecking at the dead man’s eyes and hair. They had little to say to the young knight and so when darkness fell he sought out the company of a gentler sort at an alehouse nearby. It was the alehouse of the recently widowed alewife, a woman who was also seeking gentler company this night!

The old woman was pleased to welcome such a handsome young man of prospects to her house and even more pleased to pour him many a pot of ale. More pots than there were days in the week, but fewer than there were fingers and thumbs upon both his hands, although whether it were eight or nine, not even the young knight could remember, for now he was drunk and he fell asleep upon a bench. He did not wake until the moon had done its work and the sun was thinking about taking over and it was only as a newly lit fire warmed his face that a chill passed over the knight and in a panic he returned quickly to the gallows.

His worst fears were realised, for even before he got to the crossroads he could see the hanged corpse had been stolen. Where once the body of a villain had hung, now only chains remained. He ran back to the old woman’s house, for he knew only a few people in the town and trusted even fewer. The alewife had treated him kindly and he had heard tell that old women such as she were well known for their great wit and wisdom. He fell to his knees before her. ‘Good wife,’ he pleaded, ‘if you do not help me this morning, then I must leave, lest my lord hang me for a knave in the dead rogue’s place.’

The alewife was quick to act, for she had taken a fancy to the young knight. She thought him a lusty fellow and was not about to give him up so easily. She did indeed have enough wit and wisdom for the both of them and with spade and lantern she led the knight to the graveyard where her husband had three days’ since been buried. ‘Fear not, gentle knight,’ said she, ‘for if you do all that I ask of you this early morning, then you shall be safely delivered.’ The alewife held the lantern high as the young man dug into her husband’s fresh grave, for as the old woman said, ‘we shall hang his body upon the gallows in the murderer’s place!’