8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Hard Case Crime

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

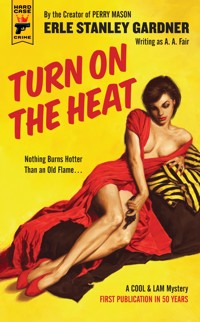

From the world-famous creator of "Perry Mason," Erle Stanley Gardner – at his death the best-selling American writer of all time – comes another baffling case for the Cool & Lam detective agency: TURN ON THE HEAT. Return to the sizzling 1940s as Bertha Cool and Donald Lam investigate a missing woman, a desperate husband, a politician with a past, and a femme fatale with a future...assuming she doesn't go to jail for murder! Featuring brand new cover art that is a posthumous collaboration between Laurel Blechman and the legendary Robert Maguire – the first new Maguire cover in decades!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Raves for the Work of Erle Stanley GARDNER!

Some Other Hard Case Crime Books You Will Enjoy:

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Raves for the Work ofErle Stanley GARDNER!

“The best-selling author of the century…a master storyteller.”

—New York Times

“Gardner is humorous, astute, curious, inventive—who can top him? No one has yet.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Erle Stanley Gardner is probably the most widely read of all…authors…His success…undoubtedly lies in the real-life quality of his characters and their problems…”

—The Atlantic

“A remarkable discovery…fans will rejoice at another dose of Gardner’s unexcelled mastery of pace and an unexpected new taste of his duo’s cyanide chemistry.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“One of the best-selling writers of all time, and certainly one of the best-selling mystery authors ever.”

—Thrilling Detective

“A treat that no mystery fan will want to miss.”

—Shelf Awareness

“Zing, zest and zow are the Gardner hallmark. He will keep you reading at a gallop until The End.”

—Dorothy B. Hughes,Mystery Writers of America Grandmaster

Evaline Harris was standing in the door, peering down the corridor with sleep-swollen eyes. She didn’t look either mousy or virginal. She said, “What do you want?” in a voice that was rough as a rasp.

“I’m an adjuster for the railroad company. I want to make an adjustment on that trunk.”

“My God,” she said. “It’s about time. Why pick this hour of the morning? Don’t you know a girl who works nights has to sleep sometime?”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and waited to be invited in.

She stood in the doorway. Over her shoulder I caught a glimpse of a folding wall-bed let down, the covers rumpled and the pillowcases wrinkled.

She continued to stand in the doorway, doubt, hostility, and avarice all showing in her manner. “All I want is a check,” she said…

SOME OTHER HARD CASE CRIME BOOKSYOU WILL ENJOY:

THE KNIFE SLIPPED by Erle Stanley Gardner

JOYLAND by Stephen King

THE COCKTAIL WAITRESS by James M. Cain

THE TWENTY-YEAR DEATH by Ariel S. Winter

THE SECRET LIVES OF MARRIED WOMEN by Elissa Wald

ODDS ON by Michael Crichton writing as John Lange

BRAINQUAKE by Samuel Fuller

EASY DEATH by Daniel Boyd

THIEVES FALL OUT by Gore Vidal

SO NUDE, SO DEAD by Ed McBain

THE GIRL WITH THE DEEP BLUE EYES by Lawrence Block

PIMP by Ken Bruen and Jason Starr

SOHO SINS by Richard Vine

SNATCH by Gregory Mcdonald

FOREVER AND A DEATH by Donald E. Westlake

QUARRY’S CLIMAX by Max Allan Collins

TURN onthe HEAT

byErle Stanley Gardner

WRITING UNDER THE NAME ‘A. A. FAIR’

A HARD CASE CRIME BOOK

(HCC-131)First Hard Case Crime edition: November 2017

Published by

Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark StreetLondon SE1 0UP

in collaboration with Winterfall LLC

Copyright © 1940 by Erle Stanley Gardner

Cover painting copyright © 2017 by Laurel Blechman, from reference by Robert Maguire

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Print edition ISBN 978-1-78565-617-0E-book ISBN 978-1-78565-618-7

Design direction by Max Phillipswww.maxphillips.net

Typeset by Swordsmith Productions

The name “Hard Case Crime” and the Hard Case Crime logo are trademarks of Winterfall LLC. Hard Case Crime books are selected and edited by Charles Ardai.

Visit us on the web at www.HardCaseCrime.com

TURN ON THE HEAT

Chapter One

I opened the door marked Bertha Cool—Confidential Investigations—Entrance. Elsie Brand looked up from her shorthand notes, and, without missing a beat on the keyboard, said, “Go on in. She’s waiting.” The staccato rhythm of her typing followed me across the office and through the door marked Bertha Cool—Private.

Bertha Cool, profane, massive, belligerent, and bulldog, sat back of her desk, her diamonds flashing in the morning sunlight as she moved her hand over a pile of papers, sorting and rearranging. The thin man in the middle forties seated in the client’s chair looked up at me with anxious, apprehensive eyes.

Bertha Cool said, “You were long enough getting here, Donald.”

I said nothing to her, but sized up the client, a slender man with grayish hair, a gray, close-clipped mustache, and a mouth which seemed more decisive than the general anxiety of his appearance would indicate. He wore blue glasses so dark that it was impossible to distinguish the color of his eyes.

Bertha Cool said, “Mr. Smith, this is Donald Lam, the man I told you about. Donald, Mr. Smith.”

I bowed.

Smith said, in the voice of a man who has disciplined himself to subordinate general impressions to exact accuracy, “Good morning, Mr. Lam.” He didn’t offer to shake hands. He seemed disappointed.

Bertha Cool said, “Now, don’t make any mistakes about Donald. He’s a go-getter. God knows he hasn’t any brawn, but he has brains. He’s a half-pint runt and a good beating raises hell with him, but he knows his way around. Don’t mind my cussing, Mr. Smith.”

Smith nodded. I thought the nod was somewhat dubious, but I couldn’t see his eyes.

Bertha Cool said, “Sit down, Donald.”

I sat down in the hard, straight-backed wooden chair.

Bertha Cool said to Smith, “Donald can find her if anyone can. He isn’t as young as he looks. He got to be a lawyer, and they kicked him out when he showed a client how to commit a perfectly legal murder. Donald thought he was explaining a technicality in the law, but the Bar Association didn’t like it. They said it was unethical. They also said it wouldn’t work.” Bertha Cool paused long enough to chuckle, then went on: “Donald came to work for me, and the first case he had, damned if he didn’t show ’em there was a loophole in the murder law through which a man could drive a horse and buggy. Now they’re trying to amend the law. That’s Donald for you!”

Bertha Cool beamed at me with a synthetic semblance of affection that didn’t mean a thing.

Smith nodded his head.

Bertha Cool said, “In nineteen hundred and eighteen, Donald, a Dr. and Mrs. James C. Lintig lived at 419 Chestnut Street, Oakview. There was a scandal, and Lintig took a powder. We’re not concerned with him. Find Mrs. Lintig.”

“Is she still around Oakview?” I asked.

“No one knows.”

“Any relatives?”

“Apparently not.”

“How long had they been married when she disappeared?”

Bertha looked at Smith, and Smith shook his head. Bertha Cool kept looking at him, and he said finally, in that precise, academic manner which seemed characteristic of him, “I don’t know.”

Bertha Cool said, “Get this, Donald. We don’t want anyone to know about this investigation. Above all, no one is to know who our client is. Take the agency car. Start now. You should get there late tonight.”

I looked at Smith and said, “I’ll have to make inquiries,” and Smith said, “Certainly.”

Bertha said, “Pose as a distant relative.”

“How old is she?” I asked.

Smith knitted his brows thoughtfully, and said, “I don’t know exactly. You can find that out when you get there.”

“Any children?”

Smith said, “No.”

I looked across at Bertha Cool. She opened a drawer in her desk, took out a key, unlocked a cash box, and handed me fifty dollars. “Keep expenses down, Donald,” she said. “It may be a long chase. We’ll have to make the money go as far as possible.”

Smith put his fingertips together, rested his hands on the front of his gray, double-breasted coat, and said, “Exactly.”

“Any leads to work on?” I asked.

“What more do you want?” Bertha asked.

“Anything I can get,” I said, my eyes on Smith.

He shook his head.

“Know anything about her, whether she had a commercial education, whether she could do any work, who her friends were, whether she had any money, whether she was fat, thin, tall, short, blonde, or brunette?”

Smith said, “No. I can’t help you on any of that.”

“What do I do when I locate her?” I asked.

“Notify me,” Bertha said.

I pocketed the fifty dollars, scraped back my chair, said, “Pleased to have met you, Mr. Smith,” and walked out.

Elsie Brand didn’t bother to look up from her typing as I crossed the outer office.

The agency car was an antiquated heap with tires worn down pretty close to the fabric. It had a leaky radiator, front wheels that developed a bad shimmy at anything above fifty, and so many rattles the engine knocks were almost drowned out. It was a hot day, and I had trouble getting over the mountains. It was hotter in the valley, and my eyes began to feel like hard-boiled eggs. The hot glare from the road cooked them right in their sockets. I couldn’t get hungry enough to make stopping worthwhile, but grabbed a hamburger along the road, ate with one hand, and drove with the other. I made Oakview at ten-thirty that night.

Oakview was in the foothill country, and it was cooler up there, with moisture in the air, and mosquitoes. A river came brawling out of the mountains to snake smoothly past the foothill country around Oakview, and spread out on the plains below.

Oakview was a county seat which had gone to seed. They rolled up the sidewalks at nine o’clock. The buildings were all old. The shade trees which lined the streets were old. The place hadn’t grown fast enough to give the city fathers an excuse to widen the streets and rip out the trees.

The Palace Hotel was open. I got a room and rolled in.

Morning sun streaming through the window wakened me. I shaved, dressed, and got a bird’s-eye view of the town from the hotel window. I saw a courthouse of ancient vintage, got a glimpse of the river through the tops of big shade trees, and looked down on an alley full of old packing-cases and garbage cans.

I looked around for a place to eat breakfast, and found a restaurant that looked good on the outside, but smelled of rancid grease on the inside. After breakfast I sat on the steps of the courthouse and waited for nine o’clock.

The county officials came straggling leisurely in. They were mostly old men with placid faces—browsing along the streets, pausing for choice morsels of gossip. They gave me curious stares as they climbed past me up the steps. I was a stranger. They knew it and showed they knew it.

In the county clerk’s office an angular woman of uncertain age stared at me with black, lackluster eyes, listened to my request, and gave me the great register of 1918—a paper-backed volume starting to turn yellow. Its fuzzy-faced type indicated a political plum had been handed to a local newspaper.

Under the L’s, I found: Lintig:—James Collitt, Physician, 419 Chestnut Street, age 33, and Lintig:—Amelia Rosa, Housewife, 419 Chestnut Street. Mrs. Lintig hadn’t given her age.

I asked for the 1919 register and found neither name. I walked out feeling the deputy’s black eyes staring at the back of my neck.

There was one newspaper, the Blade. The lettered sign on the window showed it was a weekly. I went in and tapped on the counter.

The noise made by a typewriter came to a stop, and an auburn-haired girl with brown eyes and white teeth came from behind a partition to ask me what I wanted. I said, “Two things. Your files for 1918, and the name of a good place to eat.”

“Have you tried the Elite?” she asked.

“I had breakfast there.”

She said, “Oh,” and then, after a moment, said, “You might try the Grotto, or the Palace Hotel dining room. You want the files for 1918?”

I nodded.

I didn’t get any more glimpses of her teeth, just two tightly closed lips and opaque brown eyes. She started to say something, changed her mind, and went into a back room. After a while she came out with a board clip filled with newspapers. “Was there something in particular you wanted?” she asked.

I said, “No,” and started in with January 1, 1918. I glanced quickly through a couple of issues, and said, “I thought you were a weekly.”

“We are now,” she said, “but in 1918 we were a daily.”

“Why the change?” I asked.

She said, “It was before my time.”

I sat down and started poring through the papers. War news filled the front page, reports on the German drives, the submarine activities. Liberty Loan committees were making drives to reach their quotas. Oakview had gone “over the top.” There were mass meetings, patriots making speeches. A returned Canadian veteran, disabled, was making a lecture tour telling the story of the war. Money was being poured into Europe through a one-way funnel.

I hoped what I was looking for would make a big enough splash to hit the front page. I went through 1918 and found nothing.

“Could I,” I asked, “keep this temporarily, and see 1919?”

The girl brought me the file without a word. I kept on going through the front pages. The Armistice had been signed. The United States was the savior of the World. American money, American youth, and American ideals had lifted Europe out of the selfishness of petty jealousies. There was to be a great League of Nations which would police the world and safeguard the weak against the strong. The war to end war had been won. The world was safe for Democracy. Other news began to filter into the front pages.

I found what I wanted in a July issue, under the headline: Oakview Specialist Sues for Divorce—Dr. Lintig Alleges Mental Cruelty.

The newspaper handled the affair with gloves, mostly confining itself to the allegations of the complaint. Poste & Warfield were attorneys for the plaintiff. I read that Dr. Lintig had an extensive practice in eye, ear, nose, and throat, and that Mrs. Lintig was a leader of the younger social set. Both were exceedingly popular. Neither had any comment to make to a representative of the Blade. Dr. Lintig had referred the reporter to his attorneys, and Mrs. Lintig had stated she would present her side of the case in court.

Ten days later, the Lintig case splashed headlines all over the front page: Mrs. Lintig Names Corespondent—Society Leader Accuses Husband’s Nurse.

I learned from the article that Mrs. Lintig, appearing through Judge J. E. Gillfoil, had filed an answer and cross-complaint. The cross-complaint named Vivian Carter, Dr. Lintig’s office nurse, as corespondent.

Dr. Lintig had refused to make any comment. Vivian Carter was absent from the city and could not be located by telephone. There was some history in the article. She had been a nurse in the hospital where Dr. Lintig had interned. Shortly after Dr. Lintig had opened his office in Oakview, he had sent for her to come and be his office nurse. According to the newspaper account, she had made a host of friends, and these friends were rallying to her support, characterizing the charges contained in the cross-complaint as utterly absurd.

The issue of the Blade next day showed that Judge Gillfoil had asked for a subpoena to take the depositions of Vivian Carter and Dr. Lintig; that Dr. Lintig had been called out of town on business and could not be reached; that Vivian Carter had not returned.

There were scattered comments after that. Judge Gillfoil charged that Dr. Lintig and Vivian Carter were concealing themselves to avoid service of papers. Poste & Warfield indignantly denied that, and claimed that the accusation was an unfair attempt to influence public opinion. They claimed their client would be available “in the near future.”

After that the case drifted to the inside pages. Within a month, deeds were recorded conveying all of Dr. Lintig’s property to Mrs. Lintig. She denied that a property settlement had been made. The attorneys also registered denials. A month later, a Dr. Larkspur had purchased from Mrs. Lintig the office and equipment of Dr. Lintig and had opened an office. Poste & Warfield had no comment to make other than that “in due time, Dr. Lintig would return and clear matters up satisfactorily.”

I turned through the issues after that, and found nothing. The girl sat on a stool behind the counter watching me turn the pages.

She said, “There won’t be any more until the December second issue. You’ll find a paragraph in the local gossip column.”

I pushed the file of papers to one side and said, “What do I want?”

Her eyes looked me over. “Don’t you know?”

“Yes.”

She said, “Then just keep right on the blazed trail.”

A gruff, masculine voice from behind the partition said, “Marian.”

She slid off the stool and walked back of the partition. I heard the rumble of a low-pitched voice, and after a while a word or two from her. I retrieved the file of papers and turned to the December second issue. In the gossip column was a paragraph to the effect that Mrs. James Lintig planned to spend the Christmas holidays with relatives “in the East” and was leaving by train for San Francisco where she would take a boat through the Canal. In answer to queries about the status of the divorce action, she had stated that the matter was entirely in the hands of her lawyers, that she had no information as to the whereabouts of her husband, and branded as “absurd and false” a rumor that she had learned of her husband’s whereabouts and was planning to rejoin him.

I waited for the girl to come back out. She didn’t show up. I went to a corner drugstore and looked in the telephone directory under Attorneys. I found no Gillfoil, no Poste & Warfield, but there was a Frank Warfield having offices in the First National Bank Building.

I walked two blocks down the shady side of a hot street, climbed rickety stairs, walked down a corridor slightly out of plumb, and found Frank Warfield with his feet on a desk littered with law books, smoking a pipe.

I said, “I’m Donald Lam. I want to ask a few questions. Do you remember a case of Lintig versus Lintig which was handled by—”

“Yes,” he said.

“Can you,” I asked, “tell me anything about the present whereabouts of Mrs. Lintig?”

“No.”

I thought back over Bertha Cool’s instructions, and decided to take a chance on my own.

“Do you know anything about the whereabouts of Dr. Lintig?”

“No,” he said, and then added, after a moment, “He still owes us court costs and retainer fees on that original action.”

I said, “Do you know whether he left any other debts?”

“No.”

“Have you any idea whether he’s alive or dead?”

“No.”

“Or about Mrs. Lintig?”

He shook his head.

“Where could I find Judge Gillfoil, who represented her?”

His pale blue eyes made a watery smile, “Up on the hill,” he said, pointing in a northwest direction.

“On the hill?”

“Yes, the cemetery. He died in 1930.”

I said, “Thank you very much,” and went out. He didn’t say anything as I pulled the door shut.

I went back to the clerk’s office and told the suspicious-eyed woman that I wanted to see the file in the case of Lintig versus Lintig. It didn’t take ten seconds to dig it up.

I looked through the papers. There was the complaint, the answer, the cross-complaint, a stipulation giving the plaintiff ten days’ additional time within which to answer the cross-complaint, another stipulation giving him twenty days, a third stipulation giving him thirty days, and then a notice of default. Apparently, summons had never been served on Vivian Carter, and for that reason the case had never been brought to trial, nor did it appear that it had ever been formally dismissed.

I walked out feeling the suspicious hostility of her eyes on the back of my neck.

I went back to the hotel, sat in the writing-room and scribbled a note to Bertha Cool on hotel stationery:

B. Check through the passenger lists on ships leaving San Francisco during December 1919 for the East Coast via the Canal. Find the one that carried Mrs. Lintig. Check the names of other passengers, and see if you can locate some fellow-traveler. Mrs. Lintig was full of matrimonial troubles, and may have spilled the beans to some fellow-passenger. It’s a long time ago, but the lead may give us pay dirt. The trail looks pretty cold at this end.

I scribbled my initials on the report, put it in a stamped, addressed envelope, and was assured by the clerk it would catch the two-thirty train out.

I tried the Grotto for lunch, and then went back to the Blade office. “I want to run an ad,” I said.

The girl with the thoughtful brown eyes stretched a hand across the counter for the ad.

She read it, reread it, checked off the words, then vanished into the back room.

After a while a heavyset man with sagging shoulders, a green eyeshade pulled low on his forehead, and tobacco stain at the corners of his lips came out and said, “Your name Lam?”

“Yes.”

“You wanted to put that ad in the paper?”

“Uh huh. How much is it?”

He said, “There might be a story in you.”

I said, “There might, and then again there might not.”

“A little publicity might help you get what you want.”

“And again it might not.”

He looked at the ad, and said, “According to this, there’s some money coming to Mrs. Lintig.”

“It doesn’t say so,” I said.

“Well, it might just as well say so. You say that a liberal reward will be paid to anyone who can give you information as to the present whereabouts of Mrs. James C. Lintig, who left Oakview in 1919, or, in the event she is dead, as to the names and residences of her legal heirs. That sounds to me as though you were one of these heir chasers—and that fits in with some of the other things.”

“What other things?” I asked.

He turned, focused his eyes on the cuspidor, streamed yellow liquid explosively. He said, “I asked you first.”

“The initial question,” I said, “of which you seem to have lost sight, was the cost of the ad.”

“Five bucks for three insertions.”

I gave him five dollars of Bertha Cool’s money, and asked for a receipt. He said, “Wait a minute,” and went back behind the partition. A minute later the brown-eyed girl came out, and said, “You wanted a receipt, Mr. Lam?”

“I did, and I do.”

She hesitated over the receipt, holding her pen over the date line, then looked up at me. “How was the Grotto?”

“Rotten,” I said. “Where’s the best place for dinner?”

“The hotel dining room if you know what to order.”

“How do you know what to order?”

“You have to be a detective,” she said.

I let that pass, and after she saw that it had passed, she said, “You go in for a little deduction, and reason by elimination. In other words, you need a licensed guide.”

“Do you,” I asked, “have a license?”

She glanced over her shoulder toward the partition. “It isn’t quite as bad as that.”

“Aren’t you a member of the Chamber of Commerce?”

“I’m not. The paper is.”

I said, “I’m a stranger in town. You can’t tell. I might be looking for a good manufacturing site. It would be a shame for me to get a false impression of the city.”

Behind the partition the man coughed.

“What do the local people do for good cooking?”

“That’s easy. They get married.”

“And live happily ever afterward?”

“Yes.”

“Are you,” I asked, “married?”

“No. I eat at the hotel dining room.”

“And know what to order?”

“Yes.”

“How about eating with a perfect stranger,” I asked, “and showing him the ropes?”

She laughed nervously. “You aren’t exactly a stranger.”

“And I’m not exactly perfect. We could eat and talk.”

“What would we talk about?”

“About how a girl, working in a country newspaper office, might make a little extra money.”

“How much extra?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I’d have to find out.”

She said, “So would I.”

“How about the dinner?” I asked.

She glanced swiftly over her shoulder toward the partition, and then said, “It’s a date.”

I waited while her pen fairly flew over the receipt blank. “It’ll start day after tomorrow. We’re a weekly now,” she said.

“I know,” I told her. “Shall I call for you here?”

“No, no. I’ll be in the hotel lobby about six o’clock. Do you know anyone in town?”

“No.”

She seemed rather relieved by that.

“Any other newspaper in town?” I asked.

“No, not now. There was one back in 1918, but it folded in ’23.”

“What about the blazed trail?” I asked.

“You’re on it,” she said, smiling.

Back of the partition, the man coughed again, this time, I thought, warningly.

I said, “I’d like to get the file for ’17, ’18, and ’19.”

She brought them out, and I spent most of the afternoon checking the society columns, getting the names of the persons who had attended social gatherings at which Dr. and Mrs. Lintig had been present. I arranged the names in columns and checked those which were repeated frequently enough to give me an idea of the social circle in which the Lintigs had moved.

The girl back of the counter spent part of the time on the stool, watching me; part of the time behind the partition, clacking away on the typewriter. I didn’t hear the masculine voice again, but I remembered that warning cough and didn’t try to talk with her. The name on the receipt she had given me was Marian Dunton.

Around five o’clock I went back to the hotel and freshened up. Then I went down to the lobby and waited for her. She came in about six.

“How’s the cocktail bar?” I asked.

“Pretty good.”

“Would cocktails make our dinner taste better?”

“I think they would.”

We had a dry Martini apiece, and I suggested another one. “Are you,” she inquired, “trying to get me tight?”

“On two cocktails?” I asked.

“Experience has taught me that two make a swell beginning.”

“Why should I want to get you tight?”

“I wouldn’t know,” she said with a laugh. “How could a girl working in a newspaper office in Oakview make some extra money?”

“I’m not certain yet,” I said. “It depends on the blazed trail.”

“What about it?”

“How far it’s been blazed, and who blazed it.”

“Oh,” she said.

I caught the bartender’s eye and indicated the two empty glasses. While he was fixing the second cocktail, I said, “I’m listening.”

“It’s an excellent habit,” she told me. “I try to cultivate it.”

“Ever make any money at it?” I asked.

“No,” she said, and then, after a moment: “Have you?”

“A little.”

“Do you think I could?”

“No. I think you could make more money by talking. How does it happen you’re the only pretty girl in town?”

“Thank you. Have you taken a census?”

“I have eyes, you know.”

She said, “Yes, I’d noticed that.”

The bartender filled the glasses. She said, “The cashier at the picture show says the traveling salesmen all ask her why she’s the only pretty girl in town. Perhaps that’s just the urban approach.”

“I don’t think much of it,” I said. “It doesn’t seem to get one anywhere.”

“Why don’t you try another one?”

“I will,” I said. “In 1919 this town supported an eye, ear, nose, and throat specialist. It doesn’t look as though it would support one now.”

“It wouldn’t.”

“What happened?”

She said, “Lots of things. We never list them all at once. It sounds too depressing to strangers.”

“You might give me the first installment.”

She said, “Well, the railroad had shops here. It changed the division point and moved the shops, and there was a depression in ’21, you know.”

“Was there?” I asked.

“So they tell me. Business fumbled the ball, but recovered it before the politicians grabbed it.”

“What,” I asked, “are the Blade’s political affiliations?”

“Local,” she said, “and in favor of the incumbents. There’s quite a bit of county printing, you know. We’d better finish the cocktails and get to the dining room before the local talent higrades the best of the food.”

We finished the cocktails, and I escorted her into the dining room. After we were seated, I toyed with the menu and asked, “What do we eat?”

“Well,” she said, “you don’t want corned beef hash. I wouldn’t take the chicken croquettes because they had the chicken Wednesday. If there’s veal potpie, it was left over from Thursday. You’re pretty safe on roast beef, and they do have good baked potatoes.”

“A baked potato,” I said, “with lots of butter would make up for a lot of other things. How did you happen to go to dinner with me?”

Her eyes grew large and round. “Why, you asked me.”

“How did I happen to ask you?”

She said, “Well, I like that!”

I said, “I happened to ask you because you brought the subject up.”

“I did?”

“Indirectly, and you brought it up because the man who tried to pump me, and couldn’t, went back of the partition and suggested to you that it might be a good idea.”

She let her eyes grow very large and said, “Oooh, Grandma, what big ears you have!”

“And he made that suggestion because he wanted some information, and he intimated that he had some information that he might give me in exchange for information I could give him.”

“Did he really?”

“You know he did.”

“I’m sorry,” she said, “but I’m not a mind reader.”

A waitress came and took our orders. I noticed her looking around the dining room. “Worried?” I asked.

“About what?”

“Whether Charlie will see you dining with me before you have a chance to tell him that it was a business assignment the boss gave you.”

“Who’s Charlie?”

“The boyfriend.”

“Whose?”

“Yours.”

“I don’t know any Charlie.”

“I know, but I didn’t think you’d tell me about him so we might as well call him Charlie. It’ll save time and simplify matters.”

She said, “I see. No. I’m not worried about Charlie. He’s really quite broad-minded and tolerant.”

“No firearms?” I asked.

“No. It’s been almost six months since he shot anyone, and even then it was only a shoulder shot. The man wasn’t in the hospital over six weeks.”

“Admirable self-restraint,” I said. “I was afraid Charlie might have a temper.”

“Oh, no. He’s very patient—and kind to animals.”

“What does he do?” I asked. “I mean for a living.”

“Oh, he works here.”

“Not the hotel?” I asked.