Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

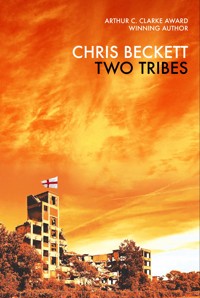

'Brilliantly and chillingly imagined'Guardian 'Explored with wit, thoughtfulness and emotional weight' Spectator As a historian in the bleak, climate-ravaged twenty-third century, it's Zoe's job to record and archive the past, not to recreate it. But when she comes across the diaries of Harry and Michelle, who lived two hundred years ago, she becomes fascinated by the minutiae of their lives and decides to write a novel about them, filling in the gaps with her own imaginings. Harry and Michelle meet just after the Brexit referendum when Harry's car breaks down outside a small town in Norfolk. Despite their different backgrounds, and Michelle having voted Leave while Harry voted Remain, they are drawn to each other and begin a relationship. From her long perspective, the way Zoe sees their world is somewhat different from the way we see it now. Two Tribes becomes a reflection on the way our ideas are shaped by class and social circumstances, and how they change without us even noticing. It explores what divides us and what brings us together. And it asks where we may be headed next.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 400

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TWO TRIBES

ALSO BY CHRIS BECKETT

Novels

The Holy Machine

Marcher

Dark Eden

Mother of Eden

Daughter of Eden

America City

Beneath the World, A Sea

Short Stories

The Turing Test

The Peacock Cloak

Spring Tide

CHRIS BECKETT

TWO TRIBES

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2020 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Chris Beckett, 2020

The moral right of Chris Beckett to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 932 5

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 934 9

Printed and bound in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Aphra, hoping you’ll find outthat other futures are available.

ONE

Harry Roberts describes a shallow valley, like an indentation in a quilt, with green pastures and trees on either side. A pair of crows cross the sky ahead of him, three women outside a bus shelter turn to watch him pass.

I managed to obtain a permit to visit the area. The shallow valley is still there, of course, but in place of pasture there are sunflowers and maize growing out of bare brown earth. There are shacks by the roadside and on the low ridge to the south stands an automated watchtower built during the Chinese Protectorate and still in use, a steep cone of stained concrete the height of a ten-storey building rising out of the sunflowers to bring forth its own strange flowers in the form of satellite dishes, cameras and remote-controlled cannons. Beside the road is an old sign, so rusty as to be almost completely unreadable apart from the initial letter W, and pierced by multiple bullet holes from the time of the Warring Factions. (Give guns to a bunch of barely trained young men and they tend to want to play with them.) What we now call the Eastern Prefecture was then a stronghold of the Patriotic League.

I feel the holes with my fingertips: Thomas testing the wounds of Christ. The past is so tenuous, so small and far away, that it always seems slightly miraculous to me that pieces of it are still around us. Driving through that soft green quilted landscape two and a half centuries ago, Harry passed the very same sign that I saw and touched. ‘Welcome to Suffolk’, it read and he reached it at half past six. He doesn’t mention bullet holes. The Warring Factions were still in the future and, though he thought of the time he lived in as a troubled one, the idea that British politics might degenerate into civil war would have seemed to him far-fetched.

I look back across the old county boundary into Essex and towards London and close my eyes to make the fields green again, with big green billowy trees, and crows high up in the cool blue sky. And I imagine his car approaching from the Essex side, billowing out its invisible fumes. It was a fairly small red car, somewhat old and scratched, and, though it had four seats, Harry Roberts was the only person inside it. He was forty-six years old. It was 26 August 2016, 250 years ago, before the Protectorate, before the Warring Factions and, I suppose, before the Catastrophe, though 2014, 2015 and 2016 had each in turn been the hottest year ever yet recorded and far off in the Arctic regions, the ice was already breaking up.

Something shifted when Harry crossed into Suffolk.

The way he puts it in his diary is that he’d been experiencing life as ‘hollow’, like the toy food that was made at the time for children to play with: hollow oranges and apples and hamburgers, moulded from coloured plastic. And yet as he crossed the county boundary, he suddenly noticed the world had become nourishing once more: the trees, the fields, the winding road, the women chatting at the bus stop in the evening sun . . . It was sufficient again, somehow. He was savouring the feeling of being alive.

Harry was an architect. Janet, his wife of many years, had left him eight months previously. They had no children, their only son Danny having died five years previously of meningitis at the age of two. Harry was driving himself, as people often did then, in a metal car with an internal combustion engine that consumed a litre of refined oil every ten minutes, to the weekend retreat of a couple called Karina and Richard. Karina was what was called a ‘food writer’ – strange as it now seems, she made a living by describing the food in restaurants – and Richard ran his own ‘actuarial consultancy’ in London, which was at that time a global centre for lending and borrowing money. They were friends of Harry’s twin sister and only sibling, Ellie. Ellie and her husband were also going to be there, and it had been Ellie’s idea that Harry should join them. ‘You spend much too much time moping around on your own, bro.’

Crawling his way out of London, whose streets at that time of day were packed with several hundred thousand crawling lumps of metal (each one of them burning a litre or so of fuel every ten minutes, and emitting the acrid residue into the air), Harry had been resenting Ellie’s interference, her attempts to organize him and make him conform to her idea of what a person in his situation ought to be doing. Why on earth would he want to waste a whole weekend with her friends, he’d been thinking, when after all he had friends of his own? But now, he had to admit, he was looking forward to it.

*

Karina and Ellie came out to meet Harry as he pulled up into the drive of the half-timbered cottage. Karina was tall and imposing, dark-haired and dark-eyed, and wearing white; Ellie was a short, lively woman in a pretty red dress, who observed her twin brother with her characteristic combination of affection, pride and exasperation. She’d worried about him a great deal during the months after Janet left, and he knew she found his passivity irritating. There were things a person could do to move on from a setback like that, and Harry seemed to her to stubbornly refuse to do any of them.

Karina led them through the house. In the living room Richard, Karina’s husband, and Phil, Harry’s brother-in-law, stood up to greet him from one of three elegant grey sofas. While Karina was very good-looking in a dark-haired Mediterranean way, Richard, with his untidy red hair, short legs and slight pot belly, could almost be described as ugly if it were not for a smouldering energy which was apparent as soon as you met him. Phil, who’d been a friend of Harry’s even before he’d got together with Ellie, was a tall thin man, rather intense, with large hands and a pointed head that he kept completely shaved.

The room was beautifully laid out, thought Harry, looking about him with a professional eye. Modern design had been cleverly married with many of the original features of the three separate workmen’s cottages that this had once been: the black wooden beams, the uneven floor.

There was a pleasing smell that mingled wood polish and old woodsmoke with the warm scented fat of a lamb dish cooking in the kitchen.

*

The two largest bedrooms, each with its own bathroom, had been allocated to the couples, but there were two smaller bedrooms, and Harry had been given one of these, at the back, which had a bathroom right next to it. (This all seemed quite opulent to Harry, given that this was Richard and Karina’s second home, but it wouldn’t have seemed as luxurious to him as it does to us now, for this was a time when almost all English homes had at least one bathroom with hot and cold running water.) He unpacked his bag, laid the notebook he used as a diary on the bedside table and checked his hair in a mirror that hung over a chest of drawers. He had a pleasant, nicely proportioned face, open and friendly even in repose or sadness. Harry smiled at his own reflection. Outside the bedroom window, the pleasantly rolling Suffolk fields glowed in the evening sun.

Downstairs the others were talking about their teenaged children but tactfully stopped when he came to join them. (Harry had learnt from his sister that the two couples had become friends because of their children: Ellie and Phil’s older son, Nathan, played in the same rock band as Richard and Karina’s son Greg.) Karina asked him about his work and where he lived. She was a very attentive host. Having put a question to him, she would compose herself into the optimal posture for conveying attention. Richard, on the other hand, rapped out his questions, one after another, absorbing the answers with a slight frown, as if continually puzzled by Harry’s reasoning.

When the evening meal was ready, Richard sat at the end of the table, with Ellie and Phil on one side and Harry on the other. By the time Karina brought out the lamb dish – her being a food writer, it was of course exquisite – they were talking about ‘Brexit’. Britain was in those days a member of a supranational body called the European Union, which, while not a federal state, had acquired many of the characteristics of such a state – a currency, a parliament, a court, a legal system, a president, free movement within its borders and so on – and it was unpopular with a substantial section of the population for that and other reasons. Strange as it seems to us now, this was a time in which virtually the entire adult population of the country was entitled to choose the government. Very occasionally other more specific matters were also put to the public in a kind of vote known as a referendum. Recently, and against the advice of almost all of the major British institutions that embodied authority and expertise, the country had voted in such a referendum to leave the European Union. British Exit. Brexit.

From our perspective, when the European Union and the British state no longer exist, this all seems pretty trivial stuff by comparison with what was to come, but it was a big thing then, and the five of them round that table were members of a class in shock. They’d been unhappy about political developments before, of course, but this was completely different. It felt personal somehow, as if they themselves were under attack. And so they grieved and raged, obsessively itemizing, over and over again, all the precious things that would be destroyed by this reckless vote, all the reasons why the vote should not have happened, all the ways in which it had been unfair.

Phil and Richard, in particular, were very agitated. In fact, they were almost shouting. Everyone in the room had some version of the received pronunciation accent, ‘RP’, characteristic of the professional middle class at the time, which lacked the marked regional variations found in the speech of less educated people. (It was the rough equivalent, I suppose, of the somewhat Sinified English pronunciation of our own more educated classes.) In the earlier conversation, before they got on to Brexit, all five of them had to varying degrees slightly softened this RP speech, as they habitually did, by making small concessions to the demotic speech of London and the south-east – ‘a glottal stop here,’ as Harry puts it, ‘a nasal twang there’ – but now, in their anger, Richard and Phil had ramped up their accents to the register with the highest possible social status. It made Harry think of frightened animals fluffing up their fur to look as big and fearsome as possible.

‘If Parliament had any guts it would simply disregard the result of the referendum,’ Phil boomed, and Richard roared that it had been ridiculous to ask the general public to make a decision on a matter as complex as this. Ellie observed more quietly that, since many blatant lies had been told by the ‘Leave’ side, the referendum result was surely invalid.

‘Absolutely!’ her husband bellowed. ‘Absolutely! And a question of this complexity can’t be reduced to—’

‘And what about Scotland, for God’s sake?’ Richard butted in. ‘There’s no mandate for Brexit there, or in Northern Ireland, or in London, or in—’

‘Or in pretty much any city with a reasonably high concentration of educated people,’ interrupted Phil, for they kept interrupting one another, not to disagree but because their need to agree was so vehement. ‘We shouldn’t beat around the bush here; this is a victory for ignorance and stupidity!’

‘Ignorance, stupidity and racism,’ Karina amended. She was worried for Sofija, her lovely Lithuanian cleaner. There’d been an ugly upsurge of verbal attacks on foreigners by strangers on the streets and on public transport, and Sofija had been told to ‘fuck off back to whatever shithole you come from’ by a total stranger at a bus stop.

Harry wondered whether this had happened to Luiza, the Polish cleaner who he’d recently let go. Luiza actually wasn’t particularly lovely, and he’d decided he’d had enough when, thinking to be humorous, she’d referred to her black neighbours as ‘dirty monkeys’.

‘Yes, and we need those people here,’ Richard growled. ‘The economy needs them. Hospitals, service industries, farms, the care sector: they all depend on immigrant workers.’

‘Apart from anything else,’ Karina said, ‘where are we going to find a decent plumber? Most of the British ones are either incompetent or crooks. And that’s assuming you can even get hold of one.’

The group shared stories for a while about various impressive services they’d received from bright, courteous, hard-working migrants from Eastern Europe until Richard moved the conversation on again by suggesting there may have been some Russian interference in the election: a relatively new theme, but one that was to become more prominent and better substantiated in the months ahead.

Then they returned, as if to the chorus of some long and tragic folk song, to a lament that the vote had happened at all. Why, why, why had a decision of such great importance been entrusted to people who were simply not qualified to understand its complexities?

They were still at the early stage, this little group, still reeling, still trying to construct a shared narrative about what had gone wrong. But they were also, though they were not aware of it, constructing a new story about themselves and their relationship to the world.

*

Harry felt oddly detached. Their aggrieved, frightened mood was out of kilter with the contentment that had come over him so unexpectedly somewhere between London and the Suffolk border. For a while he zoned out completely and instead contemplated this exciting new feeling of being reconciled with the way his life had turned out. There were new possibilities now, there was no longer a wall holding him back.

‘This country’s reputation is in tatters,’ Richard was pronouncing when Harry next paid attention. ‘We’ve made ourselves an utter laughing stock.’

‘Perhaps you could clear the plates, Rich,’ Karina suggested, and, without answering her or breaking the flow of his tirade even for a moment, Richard duly gathered up the crockery with his powerful, hairy hands. (There was a particular way, Harry thought, in which very bright, very driven, very focused people stacked plates.)

‘The smart money’s already looking elsewhere,’ Richard went on. ‘But these people don’t seem to either know or care just how much damage that’s going to do the British economy . . . ’

‘I’ve made a summer pudding,’ Karina said, ‘but shall we have a fifteen-minute break before I fetch it out?’

Harry took the opportunity to go outside for a cigarette.

These days the small road that goes past the cottage is a cul-de-sac ending in a marsh just half a kilometre further on, but the cottage still stands. It’s three dwellings again now, each one inhabited by a three- or four-generation family. Behind it is a yard with vegetable plots, chicken runs and various sheds, backing on to a field.

Maize is grown in that field now – this is a crowded country, too poor to import food – but back then it was pasture, and a row of mature chestnut trees divided it from Karina and Richard’s garden, with a bench beneath them where Harry went to sit and smoke. I close my eyes and do my best to imagine Harry there under those big, dark, rustling trees that no longer exist: a handsome, muscly, solidly built man – he played rugby football in his school days – with thick, curly brown hair. He liked to dress well, and I picture him in a light grey summer jacket, nicely pressed trousers and fashionable shoes. Like his sister he has interested, lively eyes. He was about the same age then as I am now.

Harry drew in a treacly cloud of smoke. It was a habit of his youth that he’d given up for many years but had taken up again in the aftermath of his separation from Janet. He’d stop soon, he decided. He didn’t like the clogged lungs in the morning, and he no longer really needed the primitive comfort of something warm to suck on, sorry as he’d be to give up this simple pleasure.

He exhaled slowly. How good that smoke tasted! The light was fading, the leaves were jostling about above him in the evening breeze and, even through the smoke, he caught the earthy aroma rising from the cooling ground. A car passed on the road in front of the house and a cow flicked and snuffled in the field behind him. He leant back and wriggled his shoulders into a more comfortable position. Several small bats were working the air above the garden. Mysterious creatures, he thought, and, as he smoked, he watched them make a long series of zigzag passes between him and the cottage, sometimes one at a time, sometimes two or three all at once.

Presently Ellie came down to join him.

‘You okay, bro?’

‘I’m fine.’

Birds squawked and fluttered in the tree above their heads in a dispute over the ownership of a roost, and a single feather came drifting down on to the lawn.

‘I wish you’d stop smoking,’ Ellie said as she sat down beside him. ‘I don’t want to lose you before I have to.’

‘I know. I really should. I’ll tell you what: I’ll make this my last packet.’

‘That would be good.’

They sat in silence for a while, these forty-six-year-old twins, watching the aerobatics of the little bats. Then Ellie looked round at her brother. ‘Jesus, Richard is a bit bloody full-on, isn’t he, when he gets a bee in his bonnet? And he always gets Phil going too.’

Harry took in another delicious draught of smoke. ‘To be fair, Ellie, Phil’s always been quite capable of having a good rant without anyone’s help. And there are a lot of people ranting about Brexit just now.’

‘Not surprisingly.’

‘No, of course not. I don’t think we’ve seen anything like it in our lifetimes.’

‘I guess it gets a bit wearing, though, when you’ve got other things on your mind.’

‘It doesn’t bother me at all. It’s not as if I don’t agree. I just thought a little break would be nice. It’s one of the best things about smoking, actually. You’ve got a reason to go off by yourself from time to time and take a break from human company, without it seeming standoffish or rude. A non-smoker couldn’t just say, “I’m going to go and sit by myself for ten minutes.”’

‘You need to start moving forward now, Harry. Come back into the world. It’s been a good many months, and I know I keep saying this but things really weren’t great between you and Janet for a very long time.’

He smiled. ‘I really am fine, Ellie.’ Drawing one last tarry lungful, he stamped out his cigarette and turned to face her. ‘I’m not just saying that! In fact, I’m more than fine. I feel absolutely great.’

This took her by surprise. ‘Seriously? Do you honestly mean that?’

He laughed at her bewilderment. ‘I really do. Janet was, of course, absolutely right to leave. Absolutely right! Things weren’t good between us at all. In fact, we’d had an absolutely miserable marriage, ever since . . . well, ever since, you know . . . ’ He flagged momentarily under that old weight of grief but managed to shrug it away. ‘And you’re quite right, even before that, it wasn’t great. We’d wasted more than enough time on it. It just so happens that Janet had the courage to face that before I did, and that was hurtful to my pride. But she was right and I ought to be grateful to her. I’m finally looking forward to the future.’

Ellie took his hand. ‘That’s amazing, Harry. I’m so pleased. I’ve been really worried for you.’

‘You know how it is when there’s been a persistent noise going on in the background and suddenly you notice that it isn’t there any more? It was like that driving over here. I started out every bit as miserable as usual and then, along the way, I suddenly noticed that the misery had gone! I’m sure it will come back. In fact, I think it’s quite likely that tomorrow I’ll be as miserable as ever – there’s so much to do still, so much to rebuild, so many things to grieve over – but this is a start, isn’t it? This is my head telling me it doesn’t always have to be grim. Remind me about it, won’t you, if I seem to forget?’

‘I certainly will. I’m very happy for you, Harry, very happy, and very relieved.’

‘You go back to the others, dear sis.’ He kissed her on the cheek. ‘I’ll be along in a minute.’

*

The others were still talking about Brexit when he rejoined them, obsessively going over and over what had happened like (as Harry puts it) ‘the dazed victims of a car crash’. Richard was holding forth about the contempt for experts that had been evident in the ‘Leave’ campaign. This had become a major strand in the emerging narrative being constructed by the ‘Remain’ half of the population and it was something that troubled Harry too: he had written in his diary only a couple of days before about ‘the sheer pig-headedness of climate change deniers who think they know better than people who’ve dedicated their whole lives to researching the subject’.

But now, as he settled himself back among them, he was struck by something quite different: everyone around the table was an expert. Karina was an expert on food (and also, incidentally, a qualified barrister). Phil was an international authority on land tenure in late medieval Europe. Ellie had trained for seven years to work as a GP. Richard had a Ph.D. in probability theory and advised financial institutions in the City of London on their actuarial strategies. And Harry himself was an architect, which had also taken seven years of training, even if all he seemed to do nowadays was to design people’s kitchen extensions. And that was what made this so personal. Comfortably off as they might be, none of these people were barons or oligarchs, living off the rents from accumulated assets. They earned their living by knowing things, and they were dependent on people listening to them. There had been a rising tide of irrationality around the world – religious fundamentalists, flat-earthers, anti-vaxxers – and Brexit was part of this strange new assault on what lay at the core of their standing in society.

‘You’re very quiet, Harry,’ observed Richard.

Harry shrugged. ‘Well, I’m sad about it all, obviously. I’ve always been very pro-EU. That little circle of stars on my number plate has felt very reassuring somehow: a collection of countries working together in a big bad world. In fact, I like the EU so much I’d have been happy for it to become a single state.’

‘Not sure I’d go that far,’ Richard muttered.

‘But I will just say,’ Harry said, ‘that I can sort of understand why people might be sceptical about economic experts, or even experts in general, after what happened to the financial system in 2008. That was a fairly major failure on the part of experts, wasn’t it?’

For a moment, they all glared at him. It wasn’t that they couldn’t see his point. What jarred was that Harry had unilaterally changed the rules of the conversation. Up to now this had been a collaborative endeavour, an exercise in mutual reinforcement, but he had turned it into a debate. They were reasonable people, though, and quickly swallowed their irritation, conceding in various ways that there was some truth in what he said.

‘No, that’s a fair point,’ Karina said, standing up to go and fetch the dessert. (A curious feature of early twenty-first-century British English was that people often said ‘No’ to signify agreement.) ‘I’m sure a lot of people wanted to stick it to the system.’

‘And the geography’s interesting, I think,’ Harry went on. ‘It’s almost like nationalists and unionists in Belfast. In one area it just seems obvious to most people that we belong in the EU. A few miles down the road it seems equally obvious to most people that we don’t belong there at all. I mean, here in the east of England, for instance, Norwich and the area round Cambridge voted Remain, but everywhere else voted Leave, regardless of whether you’re talking about Tory toytowns like Southwold or Saffron Walden, or rough working-class towns like Stevenage or Yarmouth.’

‘But it’s those working-class towns that are going to suffer the most if this—’ Richard began.

‘You were at Cambridge, weren’t you, Harry?’ interrupted Karina, who had returned with the pudding.

‘I was indeed,’ Harry said. ‘And of course Ellie and I grew up in Norwich.’

The little group moved into the living room for coffee and tea and Karina’s handmade chocolates, and then gradually made their way upstairs. The only one sleeping alone, Harry sat up in bed for what must have been at least an hour, meticulously writing up the day. The window was open. He could hear those big trees where he’d gone to smoke swaying and rustling in the darkness, and from time to time a night bird of some kind gave an odd tremulous cry from a wood beyond the pasture. A car came past at one point and, in his notebook, Harry imagines it out there in its own little pool of light as it moves through that gently undulating landscape, further and further away from him, until it’s swallowed up by the quietness of the night.

I run my fingers over the page. I feel the indentations and the tiny tears in the paper that he made as he pressed down with his nib, and for a moment I can almost sense the coolness on my skin of the night air around the cottage as if I was actually there, and hear its silence, and smell its earthy smell.

TWO

The day after my return to London, I walk, as usual, the three miles from my watery home to the offices of the Cultural Institute where I am employed as a historian and archivist. In my small, stuffy cubicle with its yellow cardboard walls, boxes of old notebooks are stacked on the floor and the desk. They are a collection of old diaries from the early twenty-first century, assembled many years ago by another historian for a project he never completed. The entire collection was recently sold to the Institute by one of the historian’s grandchildren, and I have the task of going through them and recording the dates they cover, the circumstances of the writer, a summary of their contents and an assessment of their authenticity. (It seems the historian paid quite generously for these old notebooks at a time when many people were struggling to find enough to eat, and there are a number of obvious forgeries among them.)

Needless to say, this cache is where I found Harry’s diaries, the most comprehensive and articulate in the collection. But what has really captured my imagination is the discovery that, by an extraordinary stroke of luck, one of the other diaries actually overlaps with his, so that I have two accounts – both genuine, as far as I can tell – of some of the same events by two people with quite different backgrounds. My colleagues were very excited when I told them this, but they all lost interest when they learnt that neither of these diaries is a chronicle of major events and neither of the diarists could be described in any way as a significant player. For myself, though, I’m still excited.

I work hard from seven thirty in the morning till six in the evening, keen to prove that my trip to Suffolk has not affected my productivity, then I head downstairs and along a corridor to the cubicle of my friend Cally who works on the records of the Warring Factions period.

‘Hello, Zoe!’ She greets me with a kiss on the cheek. ‘I didn’t think you were back until tomorrow!’

‘Well, here I am. I’ve been working on those diaries all day and I’ve had a brilliant idea. Fancy a glass of Shaoxing?’

We emerge into the intense heat of a London summer. The air is thick and treacly, with a strong whiff of drains and rotten fruit behind the cooking smells, and the street is a chaotic mass of barrows, bicycles, traders and beggars. Two militiamen ride by on an electric cart, both of them wearing shiny white helmets and those big hemispherical goggles that show them things that mere eyes would miss. (A black arrow jiggling up and down above a person’s head indicates a criminal record, or so I’ve been told, a flashing red arrow that they aren’t carrying valid ID, a blue arrow that they’re currently under surveillance.) I wait for them to pass. It’s said they have directional microphones inside those helmets that enable them to home in on conversations and my instinct is to let them know as little about me as possible, even if what I have to say is completely innocuous.

‘So let me tell you my idea!’ I say, as we launch out into the crowd. ‘You know I told you about two of the diaries linking up?’

Across the road, on the wall of the old Borough Council offices, is one of those murals from the days of the Protectorate, faded and flaking now, but with the usual stencilled portraits of the Eleven Great Sages still just about visible: Confucius and Marx at one end and Hu Shuang, the Great Synthesizer, at the other. ‘Support the work of our Guiding Body!’ says the caption beneath the picture, in English and Hanzi characters. ‘Study and apply the Nine Principles!’

‘Yeah, of course. What a coincidence! When you think of how many people there were in England even back then, and what a small proportion of them would have kept diaries, and what a tiny proportion of those diaries would have survived long enough to be collected by that historian guy.’

‘I know. It’s absolutely amazing. On the way back from Suffolk I was thinking about how to make the best use of them. I’ve spent all these years on the news media and social media archives, and recently all this time on this cache of diaries, but what’s the point of collecting information if we don’t process it into something meaningful? And I thought, those two diaries might not deal with the kinds of events that historians normally talk about, but they do tell a story. Why don’t I make them into a sort of . . . well, a historical novel, I suppose you could call it? Obviously I’ll have to add stuff to fill in the gaps, but I could use the diaries as the basis of it, and draw on all the work I’ve done on the archives to provide an authentic background.’

We steer round a hawker who’s sidled up to offer us black-market cheese.

‘That’s a bit deviant, though, isn’t it, Zoe? A novel? That’s definitely not what they pay us to do!’

‘They pay us to reconstruct the past. And that’s what I’d be doing, isn’t it? A reconstruction, based on the diaries, but also drawing on all I’ve learnt, to create a kind of snapshot of that early period when things began to unravel.’

‘But also drawing on your own imagination, which is not what we—’

‘I’ll need to flesh it out, yes. I’ll fill out the dialogue a bit. I’ll add some detail to the scenes. I might make up a story or two about minor characters to help the reader understand the historical context. But, you know, without imagination, history is nothing.’

(I really believe that, by the way. You get things wrong if you make guesses, but why collect these fragments of bone if not to try to imagine the living creature they came from?)

Cally laughs. ‘That sounds very unorthodox, Zoe. You want to be careful. Our workscreens are their property, don’t forget, and they can look at them whenever they like.’

Another pair of militiaman pass by, this time on foot, on the far side of the road. One of them looks in our direction. His goggle eyes make me think of those huge praying mantises I keep finding on my window ledge. It’s impossible to tell if he’s focusing on us or something else, let alone what arrows he sees above our heads, though I know that over both of us there hovers the modest white star that signifies a Level 3 Associate of the Guiding Body. (It confers a bit of status, but also makes us more visible.) In any case, he turns back to his colleague and they carry on.

‘I thought the idea would appeal to you,’ I say. ‘Life is all about guesswork, isn’t it? Everyday life, I mean, not just history. We create the world from fragments all the time. We get it wrong, of course, but if you’re not prepared to make guesses, there’s hardly a world left at all.’

THREE

On Monday morning, as Harry was getting ready to drive back to London, Charlie Higgins left his parents’ house on the outskirts of the town of Breckham, and walked to the Heath Road to be picked up from his usual spot opposite the empty brick shell of the old suitcase factory. He was twenty-four, a kind young man, good with animals, loved by his little nephews and nieces, popular with elderly neighbours, but he wasn’t particularly bright or good-looking and he had no special talents apart from being big and fairly strong.

He climbed into the minibus and it moved off again, burning up diesel oil inside its four cylinders at about five or six litres an hour. ‘All right, Jake?’ he called out to the driver. ‘All right, everyone?’

‘Morning, Charlie,’ Jake said. The others grunted.

Ben, Brett, Tom and Mac were already on board, along with the two Polish guys, Clem and Alex. And today, as on every other day, Charlie braced himself for the teasing he would have to put up with on the six-mile journey, and for the things which he suspected were teases, but wasn’t quite sure. He’d never been good at detecting irony.

It wouldn’t be quite true to say that Charlie was picked on. A lot of teasing went on between the other men too – it was the main source of entertainment on this daily commute – and the two Poles in particular had to put up with a good deal of banter, but (at least from Charlie’s perspective) everyone else, the Poles included, gave as good as they got, while he could never find the right tone, the right mixture of playfulness and aggression. His attempts at jokes usually fell flat, and even when he did get a laugh, he was uneasily aware that the others were probably laughing at him rather than with him. Yet if he abandoned altogether the exhausting many-layered game of male verbal jousting and tried to be straightforwardly friendly, that didn’t quite work either.

‘How was Thailand, Mac?’ he asked one of the older men, who’d been away on holiday the previous week.

‘Thailand was shit, mate,’ Mac said. ‘Or at least the bits of it I can remember. Can’t speak for the rest.’ Charlie thought that Mac was making some sort of joke, but he wasn’t sure if he understood and had no idea how to follow through. It was as if Mac had deliberately made it impossible for Charlie to continue the conversation.

Charlie’s biggest conversational successes were on the subject of Brexit. There were certain verities that you could express on that topic, without any irony, and still be sure that everyone would agree (or everyone except the Poles, who usually remained silent on the topic, though Alex would occasionally mutter at the Englishmen that they were all bloody idiots). ‘Why can’t they just get on with it?’ Charlie would say, for instance, or ‘Just fucking leave!’ and nine times out of ten he would earn growls of assent, or even have the gratifying experience of having started a conversation.

So he tried it again this morning. ‘What the fuck’s happening with Brexit?’ he said. ‘It’s doing my fucking head in. Why don’t we just walk away?’

But it didn’t work this time. The others liked to go over Brexit fairly regularly, rehearsing and refining the various articles of their steadily hardening tribal creed, but there were limits all the same and Charlie had said something quite similar on Friday.

‘You just want us all to cheer you like we did last week, don’t you, Charlie?’ observed Ben the engineer, who was crueller and less patient than the other men. And for the rest of the journey, Charlie felt his shame prickling in the roots of his hair.

They didn’t dislike him. He knew that. When he met them individually at the plant, they would be perfectly pleasant to him, even Ben, and some could be quite affectionate. Jake, who was also the oldest of them, could be positively paternal. But what saddened him was that all of them could see through him and knew him for what he was, which was to say, nothing special. He didn’t dispute their judgement. It was how his dad and his brothers saw him too, all three of them more able and more worldly than Charlie. Still, it would be nice to find people who saw something else in him – and not just his mum and grandma, who doted on Charlie as the baby of the family, but were generally agreed to be nothing special either.

Charlie and the other men all worked in a small power station on the edge of a forest, where straw and other farm waste were incinerated to generate electricity. Some of the men had responsibility for various pieces of machinery, others for driving the fork-lift trucks that were used for unloading bales of straw from lorries and moving them about the plant. Charlie’s job was mainly sweeping up and scrubbing down. He was heading across to the main building where he’d receive his instructions for the morning when Jake called him back. ‘Don’t take any notice of Ben, Charlie,’ he said, patting him on the arm. ‘He’s a sarky sod. I think it’s great the way you speak out for Brexit. You should be proud of yourself. You’re standing up for your country. You’re standing up for what the people voted for.’

FOUR

Harry emailed his wife Janet and asked to meet. Her response was wary: What are we going to talk about that we haven’t talked about before? Harry had been extremely awkward over the past few months. He’d refused to accept a separation that he hadn’t chosen and he still lived in what had been their home, hating it, but carrying on anyway, all by himself in the rooms of the tastefully renovated house which had, a hundred years ago, housed an entire Edwardian family.

I’m not going to be difficult any more, I promise, he told her. I really do want to move things on.

They met that evening in a pub in a part of London known then as Wood Green. (I’ve looked for the building but it no longer exists. The Wood Green area was badly damaged by street fighting during the Warring Factions.) Harry arrived at 6.50, determined not to irritate his wife by being late. Janet arrived at 7.10. She had a rather long face suited to seriousness – when they first met she’d reminded Harry of the twentieth-century author Virginia Woolf – and as she stood just inside the door, looking round for him in the big, shabby, wood-panelled room, her whole body seemed to him to be braced in anticipation of having to ward off unreasonable demands and unwelcome pressure. When he stood up and called out to her, she approached him uneasily and stood as stiffly as a statue as he greeted her with a kiss on the cheek. He’d already bought her a glass of Merlot and she eyed it without enthusiasm as she sat down. ‘I can’t stop very long,’ she told him. She had grown up in Scotland and still had a trace of a soft middle-class Edinburgh accent.

‘Of course,’ he said. ‘But I honestly don’t think this needs to take much time.’ He drew a breath. There were so many intense and contradictory emotions wrapped up in the simple fact of being in her presence.

She did that particular kind of shrug that means, ‘I’m in your hands. I have no idea what this is about.’ Harry felt as if he was standing on the bank of a cold river, steeling himself to dive in.

‘Okay, well, I wanted to say first of all that you were quite right about all this, and you were very brave. And I was wrong and a coward.’

She studied his face for several seconds. ‘I suppose you’ve met someone, have you?’

‘No, I haven’t. I haven’t even tried yet.’

She seemed unsure whether to believe him or not. Their last communication had been an exchange of text messages only a couple of weeks ago, and he’d been as difficult and hostile as ever. She couldn’t imagine what else could possibly have brought about such a sudden change of heart.

‘But I’d like to meet someone else,’ he said, ‘and I know you would too. You’re absolutely right. You’ve been right all along. We’ve wasted far too long over this. Danny would always have stood between us in one way or another.’

There were tears in her eyes now, and that brought tears into his.

‘And another thing you’ve always been right about . . . ’ he said. Here he had to pause to collect himself. ‘Another thing you’ve been right about is that what happened to Danny is my fault.’

Harry’s hands were shaking. He’d never conceded this before, never spoken it aloud to anyone at all. Janet had been a very anxious parent and Danny an exceptionally precious, almost miraculous child who’d arrived after many harrowing years of fertility treatment, just at the point when they were thinking of giving up. Janet had worried constantly about his health and often called the doctor. The locum GP who’d been on call that night had suggested that, unless his condition deteriorated, they leave it to the morning before getting Danny seen. Harry had been fine with this, but Janet became convinced that his condition had become worse and wanted to take Danny to a nearby hospital to be checked out. Harry had resisted this.

They could have been seen at the hospital completely free of charge – an extraordinary thing, of course, from our perspective, and pretty much unprecedented in human history – so that, unlike most parents these days, Janet and Harry weren’t faced with the agonizing dilemma as to whether this was the moment to dip into the roll of yuan stowed under their bed, or whether they should hold their savings back for a still more serious emergency in the future. But it was ten past eleven at night, Harry was fed up with Janet’s constant fretting, and he was very tired. He didn’t fancy sitting up for hours, drinking nasty coffee out of cardboard cups under the cold white lights of a hospital waiting room. He told Janet she was being silly and that he’d had enough of these dramas. By the time it had become obvious that their son was very ill indeed, it was too late.

But now, quite unexpectedly, Janet reached out and put her hand over his. ‘Well, the other nine times I insisted on having him checked out, you were right. So you were very unlucky that this was the occasion you finally took your stand. I had a part in this too, Harry. I’d cried wolf once too often. Plus, I’m a grown-up and if I really didn’t agree with you, I could have taken him to the hospital myself.’

These had always been Harry’s defences against the charge that he was to blame for his own son’s death. Just as he’d never accepted responsibility, so she had always denied that her own behaviour had played a part.

Janet laughed. Her hand was still over his and she gave him a friendly squeeze. ‘Look at the pair of us! Blubbing our eyes out together in the middle of a pub!’

Blubbing our eyes out was something of an exaggeration, Harry thought, but his eyes and hers were certainly moist. He took his hand from hers to put it round her shoulders and give her a kiss. She didn’t feel like a statue this time, and she even kissed him back, though she withdrew as quickly as she could without actually being unfriendly.

‘That’s better,’ he said. ‘I hated us being enemies.’

She laughed. ‘You insisted on us being enemies, Harry.’

‘I know.’

‘And yet you also insisted we shouldn’t split up.’

‘I know. It made no sense, did it?’

He studied her face. That sweet seriousness, that intensity. For the first time in many months, or even years, he remembered a time when her Scottish voice had sounded soft and caressing and not prim and taut. A single ember was still glowing even now under all that cold grey ash. Perhaps, after all, they—