Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

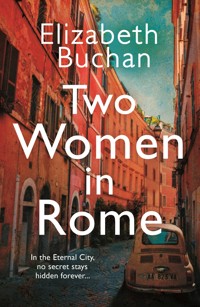

A BEAUTIFULLY ATMOSPHERIC TALE FROM THE PRIZEWINNING BESTSELLING NOVELIST ELIZABETH BUCHAN In the Eternal City, no secret stays hidden forever... Lottie Archer arrives in Rome excited newly married and ready for change as she takes up a job as an archivist. When she discovers a valuable fifteenth-century painting, she is drawn to find out more about the woman who left it behind, Nina Lawrence. Nina seems to have led a rewarding and useful life, restoring Italian gardens to their full glory following the destruction of World War Two. So why did no one attend her funeral in 1978? In exploring Nina's past, Lottie unravels a tragic love story beset by the political turmoil of post-war Italy. And as she edges closer to understanding Nina, and the city draws her deeper into its life, she is brought up against a past which will come to shape her own future. Praise for Elizabeth Buchan: 'It's a gem of a book... Beautiful, elegant.' Marian Keyes 'Intricately plotted and beautifully written.' Katie Fforde 'An amazing, emotive, heartbreaking but also ultimately uplifting novel. I really loved it.' Laura Barnett

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 439

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Elizabeth Buchan

Daughters of the Storm

Light of the Moon

Consider the Lily

Against Her Nature

Beatrix Potter: The Story of the Creator of Peter Rabbit

Perfect Love

Secrets of the Heart

Revenge of the Middle-Aged Woman

The Good Wife

That Certain Age

The Second Wife

Separate Beds

Daughters

I Can’t Begin to Tell You

The New Mrs Clifton

The Museum of Broken Promises

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Elizabeth Buchan, 2021

The moral right of Elizabeth Buchan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 532 7

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 533 4

Australia and New Zealand Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 443 7

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 534 1

Design and typesetting www.benstudios.co.uk

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Alexia, Flora and Finian who have brought much joy

‘I thought I knew everything when I came to Rome,but I soon found I had everything to learn’

Edmonia Lewis

Italy

March 1977

HE WRAPPED HIS ARMS AROUND HER AND DREW HER EVEN closer. She knew then that he was telling her that he loved her but could not trust himself to say so.

It did not matter.

For that moment at least, tender and choked with emotion, they were at peace after the turbulence of longing and desire.

They were staying in a hilltop town a short train journey away from the big city. The hotel was inexpensive, clean and discreet. The view from the window was of the plain below, where the spring narcissi massed, and a milky-looking mountain in the distance.

Lying open on the floor beside the bed was her notebook, containing her botanical painting of the narcissi. On the opposite page was a transverse section of its seed head. She had taken her time to select the best specimen and dissected it with the sharpened knife she kept in her bag.

To keep off dangerous subjects – what had taken place between them, the future – they discussed the two paintings they had seen earlier in the morning, sightseeing.

The town’s ducal palazzo was run-down and shorn of artefacts. Pacing behind the guide, who was so desperate that he resorted to pointing out the guttering, they had escaped to its museum, which had nothing in it except for the ducal chair and an exquisite miniature painting of Bathsheba bathing.

The label stated that it had been discovered during restoration work in the palazzo and later authenticated as an original from a book of hours commissioned by the then duchess in 1489 and painted by Pucelle fils, a celebrated master.

Its subject was Bathsheba bathing in a pool with a fountain playing. It showed her with milky-white, unblemished skin and a slender waist above broadly curving hips and exposed pudendum – a glorious, jewel-like homage to lust. And yet, by placing her in the water, with King David gazing down on her from a distant palace, the painter was cleverly keeping her at one remove. Beware of sensuality was the message.

She had studied it for a long time.

Close by, in the church on the piazza, was another medieval painting, this time of the Annunciation. Here, the Virgin sat peacefully in the garden, wearing a cloak of the most intense blue. A rabbit and a mouse sheltered under her skirts. An archangel was winging down, bearing a lily.

She had stood in front of it, and the colour of the Virgin’s cloak had shimmered, and grown deeper, burning into her vision: the deep, deep blue of peace and certainty.

Now she stirred in his arms.

‘All right?’ His breath fell on her cheek.

‘The blue makes the heart sing.’ She was beginning to feel sleepy. ‘It’s remarkable.’

‘Made from powdered lapis lazuli. Probably.’

‘Is it?’ She looked up at his face. Since their time together was always short, she liked to take an inventory of every expression. ‘How did they convert it into paint?’

‘Water and gum Arabic. But it was only applied at the last minute.’ He, too, was drowsy. ‘It would be used for her cloak, and she would be wearing it at every stage of her life as a mother. Annunciation, birth, flight into Egypt, taking Christ to the temple …

‘The blue that was used for the Virgin’s cloak, what they called the azur d’outremer, was the most expensive,’ he continued. ‘A fortune. It was specified in the contract. So much, and no more, to be bought by the painter. It was also spelled out to the artist how he could use it.’ The words were muffled. ‘No artistic freedom in those days. The artist did what he was told.’

While he had been a student at university, he had read up on the subject, claiming it was a relief from the intensity of his main study.

‘A fabulously expensive cloak to wear in the stable,’ she said. ‘Crazy.’

‘Also worn on the flight into Egypt.’ His voice darkened. ‘Watching him on the cross. Taking her dead son in her arms and draping it over him.’

‘Is her cloak ever red or green?’

‘Not at that period. Later, perhaps.’

‘I bet some of the forgers made that mistake.’

Their hands entwined and they were silent until he said, ‘In those days, there was an entire language of colours. Each one had its place in a hierarchy. Everyone understood what they implied in a way that we don’t.’

Later, he sat on the edge of the bed staring out of the window, his hands clasped loosely between his knees. A trace of moisture gleamed on his shoulder blades. She reached out and pressed her finger gently on his spine.

‘The early representations of Mary usually show her with a flat skin tone.’ He turned his head. ‘Unless they were taught by a master, the younger painters did not understand that nothing is flat and smooth. But, as they grew older, and if they were not too arthritic, they learned how to extend the colour range … vermillion, yellow ochre and lead white. Pucelle fils was one of those painters.’

‘How would you paint me?’ she asked softly.

He lay down beside her and propped himself up on an elbow. ‘Grey skin undertones and … yes, blue shadows under the eyes, long brushstrokes to convey your silky skin. I would command the white lead to be ground and I would mix it with just a shade of black bismuth to capture the movement in your face.’ He ran a fingertip over her eyelids. ‘Then I could paint the light in your eyes and expose you: both wary and ecstatic in equal measure.’

She pulled him down to her and kissed him lingeringly and deeply.

Regrets? They would be hammering inside his skull. And, she suspected, the beginnings of hatred for her. Or what she stood for.

The church bells sounded in the distance with a silvery shudder of sound. Vespers. She felt the ripple go through him. Guilt? Longing? She pressed her head against his chest. ‘Go on,’ she said. ‘Say what you always say. What you must.’

He addressed the ceiling. ‘I am … wrong being with you.’

Her heart thudded a little. ‘But you say you can’t be without me.’

‘No, I can’t, but I must try.’

It came as no surprise, but it still hurt. ‘You’re in danger of sounding like a Desert Father. Women’s bodies are disgusting and sinful.’ She shut her eyes. ‘I’ll never understand why the views were so pervasive for so long. Or why chastity is considered heroic.’

‘Listen,’ he replied. ‘While I’m lying here with you, I can think only of you and your warmth. Of your beautiful body. I feel sick at the thought someone else might touch it. That you might turn to another and smile at him in the way you smile at me. It would drive me to madness.’

She felt herself melting, dissolving with happiness.

‘When I’m here with you there’s no room for anything else. That’s the reason why.’

What a waste of so many lives, she thought. The battle for chastity took up so much energy and the perceived enemy, which was lust and desire, refused to die. Anyway, surely it was possible to lust and to serve God?

He put his arm across his eyes.

‘There are many ways of achieving peace and equality and a good life,’ she pointed out. ‘They may not include God, but they have everything else.’

He rolled over and looked into her eyes. ‘You’re talking politics.’ His face was magnified above hers. ‘If you are, it suggests you don’t understand about faith.’

‘You’re mistaken. I do have a faith. Or rather beliefs.’ She was stung into revealing more than she normally would. ‘But they’re not the same as yours.’

‘For the love of God.’ The words were pulled from him.

She moved away from him and swung her legs to the floor. ‘I don’t think God has anything to do with this.’ She walked over to the window. ‘With you and me.’

There was a difficult silence and she cursed herself for spoiling their brief and precious time together.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said.

Still the silence.

‘Tell me about the books of hours,’ she tried again.

She heard him get to his feet, pad over, and she turned to face him and buried her face in his chest.

‘They were powerful.’ His voice echoed in his chest against her ear. ‘They told you how to spend your day: when to pray, how to pray. There were calendars, and texts, and special pleas. Women gave them to their daughters when they were sent from home to marry. Legally, it was the only possession they had the freedom to give away.’

She absorbed the information. ‘If I had been a mother, I’d put in private messages.’

‘What would you say?’

His gaze disconcerted her. Did he know anything? Did he suspect that, although her life had become his, it was also not his? Her secrets could not be for him and would never be for him. ‘I wouldn’t know where to begin.’

He touched her chin with a finger. ‘I think you do.’

Her unease deepened. ‘Remember me. That’s what I would say.’

Remember me.

CHAPTER ONE

LOTTIE ARCHER HAD KNOWN FOR SOME TIME THAT HER nature was divided – she put it down to the fact her mother had given her away at birth and her father was unknown from the word go.

Which life is ever nourished in ideal circumstances? Not many; but Lottie’s had fallen short from the start without anyone to guide or guard her. There had been no flowing, and unconditional, tenderness to weep with her over bruised knees, or to apply sticking plaster to the terrors of growing up. No one to say with total conviction: It will be all right.

The reasons for her abandonment might have been noble or ignoble but Lottie was never informed, either by the care homes she frequented or by the foster parents who took her in as a teenager and with whom she – sadly – had nothing in common.

She grew to see that her abandonment was hers with which to cope, and hers alone, and she hugged its whys and wherefores to her inner self, no doubt hampering her emotional development in doing so.

There had been dark times.

The scissors.

The uneaten meals.

But the memory of the weapons that she had used against herself had been banished to a dark recess in her mind. Useful experience. Never to be repeated – but something that added an edge, a serration, to her character.

Occasionally, during those years, a counsellor suggested that she unburden herself but, at those times, she was not sure of what she wished to achieve.

It was sufficient for her to understand that one half of her loved order, procedures and clarity – and she was superb at those. The other, wilder half could, on occasion but not always, take risks and had been known to dance around (the permitted areas) of Stonehenge at midsummer and to climb Mount Kenya without a sensible sleeping bag.

Three weeks ago, she had accepted another risk by marrying, and now she was lying beside Tom, her husband, in the apartment in Rome in a newly purchased double bed.

To say she was astonished at herself was an understatement. Marriage had never been part of her plan and, even more astonishing, she had only known Tom for nine months.

Tom arrived in Lottie’s life on a hot July day. Her close friend Helena, who was getting married for the second time, had insisted her attendants, of which Lottie was one, should wear pink. Neither the dress nor the colour suited her. But, because she loved Helena, she laced herself into it and resolved to avoid the photographs. Tom had spotted her skulking behind a pillar and introduced himself.

Halfway through their conversation, he broke off. ‘I don’t think you like your dress. Your idea or the bride’s?’

It was a neat insight and she burst out laughing. ‘Truthfully, I hate it.’

‘It doesn’t matter, though,’ he said. ‘You’re lovely.’

She looked at him and her stomach did an extraordinary contraction. ‘So are you,’ she said. ‘And I’m sure that we know each other.’

‘That’s good,’ he said. ‘It means there’s something there.’

They went to bed that night, a glorious, slightly drunken, surprising encounter in an upmarket hotel with a marble bathroom and a stack of white towels.

The pink dress was abandoned on the floor, never to be worn again.

Partly, Tom snared Lottie with his gift for listening, which meant he paid as much attention to the unspoken words as the spoken ones. Partly, she loved his body, from which she took as much pleasure as she hoped she gave him. Not handsome, with a nose that was a shade too long, his charm came from his lean and rangy energy and it snared her.

He was the only one of her lovers who had got her to talk about her childhood, and she found herself telling him about the care homes and the fostering.

‘I survived,’ she said.

He stroked her hair back from her forehead. ‘Not funny, though,’ he said. ‘Not for a child.’

‘I yearned for the safeness of a mother – except my mother had been anything but safe. I think I wanted relief from being responsible for myself and I was angry that I had to be.’

‘Yearning can be cruel,’ said Tom. He paused. ‘Did you ever try to find your parents?’

She felt the old anguish stir. ‘Tom, do you mind if we change the subject?’

He seemed perfectly at ease with her retreat. ‘Fine,’ he said gently. ‘We all have no-go areas.’

One way or another, Lottie’s love affairs were always conducted at long distance – Freudian, said Helena. Tom lived in Rome and so this affair looked set to conform to the same pattern, but he had other ideas and wooed her with tenderness … and stealth.

There had been many phone calls between London and Rome and those slightly concerning sessions on FaceTime that made her look haggard – ‘Rome has so many things going for it, I promise’ – and weekend meetings facilitated by budget airlines.

And what of Tom’s previous lover, who had moved out three years previously?

‘Clare found someone else,’ said Tom. ‘And she chose to leave. It was bad at the time. I missed her very much. Then one day I didn’t.’ His gaze raked past Lottie’s shoulder into a past – and a no-go area? – about which she knew little. ‘It had run its course.’ He turned his attention back to Lottie. ‘I learned that, at forty, you have to re-educate yourself for the rest of life. Clare’s leaving was my lesson that the ambitions and ideals that were good for the first half of my life needed adjustment. The more I thought about it, the more I realised that it was quite normal.’

That struck Lottie as profoundly true.

He took her hands in his. ‘We both have baggage from the past. Let’s just cut off previous labels.’

‘Done,’ she said.

Just before Christmas, Tom phoned Lottie in London. ‘The post of chief archivist has come up at the Archivio Espatriati. Why don’t you apply and come and live in Rome?’

Why would she? Her work as Principal Records Specialist at Kew would lead to promotion. She was established and enjoyed her good reputation.

Why would she? The risk-taker asserting herself? Had her feelings for Tom so deepened that a sea change had taken place?

‘The Italians are wonderful,’ said Tom. ‘They are so right about many things and you speak good Italian.’ He added: ‘I love you, Lottie.’

That was the first time Tom had said it and, to her surprise, she experienced pure joy. Normally reticent, she found herself responding – and the words were almost new to Lottie. ‘I love you, too.’

She got the post and, before she took it up, Tom launched the next phase of his campaign.

He took her skiing in Austria. Nothing too expensive, but not cheap either. St Anton was less glitzy than many, but it had an old-world charm and the trails and lift networks linked delightful Alpine villages.

‘You can ski all day without repeating a run,’ said Tom. ‘I like that.’

They skied like there was no tomorrow and, at night, they dined and wined and fell into bed. On the final day, they took the ski lift up the steepest mountain. At the top, Tom sent Lottie a look over his shoulder. Race me.

Erotic. Testing. An invitation into new territory.

Lottie pushed herself fast down the terrifying piste. Tom was just ahead but only just. The speed was stupidly reckless but she responded to its danger with surging blood and an abandonment to elemental sensations.

The air sliced at her cheeks, her stomach heaved with apprehension and excitement, her legs ached. She caught up with Tom and he turned his head for a second and they exchanged a look of complete understanding.

At the bottom, breathless and ecstatic, stripped of everything except exhilaration, she collapsed into his arms.

‘Marry me, Lottie.’

‘What?’

‘Marry me.’

Lottie was unable to respond instantly.

‘Say yes.’

Adrenalin coursed through Lottie. Love. New job. Profound change. The tally was seductive. ‘Yes. Tom, yes, I will.’

Tom played his trump card with exquisite skill. ‘I want to share my home with you, Lottie. You’ve never had one.’

True: and the reminder made her cry.

As a child, she had had no real home. As an adult, she had lived – along with a vast collection of pot plants – in a series of rented flats that were never quite as she wished them to be because she never stayed long enough. In contrast, Tom had lived in the apartment in the city centre and held down the same job for over fifteen years.

‘You can come and go as you please,’ he said, blotting her tears with the ball of his thumb. ‘The travel is easy.’

He had kissed her in the way that was increasingly familiar and which she had grown to love, and she was taken aback by the strength of her desire to accept what he offered. The decision was not without struggle because her habit of self-containment was so entrenched. Guarded, said Helena during one of those talks that were supposed to be cathartic and useful but so very often weren’t. Solitary.

She could not swear that she knew Tom. Not through and through, at a deep level. But her instincts, and everything she had learned about him so far, told her he was kind and honourable. Plus, she admired the work that he did at the British Council, an institution that had been created to facilitate good relationships between nationalities, and of which he talked with passion.

Helena was hobbled by a rotten early pregnancy and Lottie turned to her other great friend, Peter, for advice. ‘Hold the decision until I get there,’ he said. ‘I’m coming over for the weekend.’

Peter was an actor, a shambling figure who possessed an uncanny ability to appear neat and energetic on stage and considered himself a Shakespearean scholar – Shakespeare was there to be plundered – and he threw quotes around like confetti.

He, Helena and Lottie shared a friendship from university days that had evolved and matured over the decades, the kind that did not ask questions when things were bad. They understood the dark places in each other’s spirits, never lost faith and, even under provocation, found reserves of patience.

Lottie and Peter took themselves off to the Campo de’ Fiori for a dish of pasta. Lottie willed a cheering aphorism to tumble from Peter’s lips. None came.

She poured him a glass of wine. ‘“Too rash, too sudden, etc., etc. …” is what you’re thinking.’

‘I’m not saying anything.’

‘You don’t have to.’

He put down his fork. ‘You’ve tomato on your chin, but it hasn’t ruined your beauty.’

She wiped it away. ‘And?’

‘OK, how long will you be here for? Until you’re carried out feet first? You fought hard to get where you were professionally. Is the new job in the same league?’

‘There’s potential,’ she answered carefully. ‘Is my chin OK?’

‘More than. What about your Englishness?’

‘Englishness? This is not Our Island Story. Tom will retire when he’s sixty-five. Or earlier, if he wants. We can be flexible.’

‘And if you want to return to the UK before Sir retires? What if you find living here difficult?’

‘I know, I know,’ she said. ‘What am I doing?’

He tipped back his chair. Rather dangerously. ‘Tell the truth, my darling. What do you know about him?’

‘I’ve told you.’ Lottie assembled the correct order of response. ‘Brought up in Cornwall. Lived in Rome for fifteen years. Good job at the British Council. Previous relationship but no children.’ She reached over the table and placed a hand on Peter’s forearm. ‘What are you trying to tell me?’

‘Is he real? Or the too-good-to-be-true real? You’re smart and sharp and you should use your smartness. Have you got past the surface of the affable, intelligent bringer of good tidings to the natives of foreign countries who are keen on culture? What does he actually do?’

‘Plenty.’

Peter frowned. ‘He had a long relationship, which he seems to have got over in a trice’ – Lottie made a protesting noise – ‘and is proposing to nail you down within months of meeting. Are you sure he isn’t Bluebeard?’

‘It was three years ago.’ She felt a flicker of outrage. ‘And anyway, emotions do not conform to timetables.’

‘Sorry.’

‘But I know you’re protecting me.’ These days, Lottie’s appetite rarely failed, and she occupied herself winding the final coils of pasta on to her fork. ‘Do you suspect him of something?’

‘Nothing is ever not possible.’

Lottie stared at Peter. ‘I think we need more wine.’

After the meal, they wandered the streets fanning off the Campo de’ Fiori. ‘This is the street of the chest maker, the arrow maker, the hat maker.’ She translated the names for Peter, and he insisted on taking her into a boutique selling hats. ‘You’ll need a proper beret.’

‘Why?’

‘Because you will look more the part.’ He placed an overlarge black beret on her head and stepped aside so she could see her image in the mirror. ‘Perfect.’

‘I look like a cross between Gigi and a paratrooper.’

‘A very stylish one. I’m buying it and you will wear it. It’ll be your talisman.’

Wearing the beret, Lottie took Peter the next day to St Peter’s and made him stand in front of Michelangelo’s Pietà. For a few seconds, the crowds around it parted and they were granted a spectacular view.

‘What do we see?’ He tucked his hand under Lottie’s elbow.

A young woman held the body of her dead son in her lap. Her beauty, and its beauty, took away the breath. Even more astonishing was the artistry. To balance an adult body in a lap was difficult enough in life. In marble, it was extraordinary.

‘Classical beauty married to naturalism.’ Lottie sounded lame and limited, but it was impossible for her to convey how deeply the Pietà affected her.

He sent her one of his more actorly glances. ‘Yes, but what do you feel?’

‘What I feel … what hits me,’ Lottie’s throat constricted, ‘…is the grief, all conveyed in stillness. I’m not a parent, but how do you survive something like this?’

Peter shot her a look. ‘You don’t often say that sort of thing,’ he remarked.

It was true. Family. Parents. Children. Lottie had no experience of how they slotted together, or of how the ropes of obligation and affection could bind you tight.

‘I sometimes think I missed out,’ he admitted. ‘Too busy being the actor. Didn’t leave room.’

The weekend over, Lottie went with Peter to see him off to the airport. He gave her a kiss. ‘Have you made up your mind?’

‘You’ve made me think hard,’ she replied. ‘Thank you for that.’

‘And?’

‘I’m going ahead.’

Here she was. In Rome – and it was spring.

Lottie turned her head to look at Tom sleeping beside her, taking delight in his warmth, the long limbs and the snuffle as he hauled the sheet over his shoulder. She reached over and placed a fingertip on his mouth very, very gently.

She moved closer to him, closed her eyes and went to sleep.

Not for long. Tom’s phone rang, a noise that tore into the peace, and they both groaned. Tom swung out of bed and picked it up. ‘Go back to sleep,’ he said, and padded into the next room.

He returned several minutes later and switched on his bedside light. ‘There’s been an explosion. I have to go.’

Horrified, she exclaimed, ‘Are people hurt? Dead? But why you? Won’t the police and the authorities deal with it?’

‘I need to see if some colleagues are OK.’

‘Your colleagues? But it’s the middle of the night.’

‘Apparently a bomb went off where a couple of them live. They might need help.’

‘A bomb …’ she echoed in a stupefied way.

‘It’s not unknown.’ Tom grabbed his jacket, checked over the pockets in a methodical way.

‘Let me come with you?’

But he was already out of the door.

Lottie grabbed her jeans and top, struggled into them and followed Tom down the stairs. He was in the courtyard, talking to a man. In the half-light they seemed more ghost than human. After a moment, they loped towards the street where a car waited.

Lottie stood for quite a time in the courtyard, listening to the night sounds. A doubt crossed her mind, followed by a question, neither of which she could resolve.

She made her way back to the apartment and to bed.

He did not return until dawn. Lottie had slept only in fits and starts and watched him sit down heavily on the bed. ‘Three dead and one badly injured,’ he said. ‘Carabinieri who had been lured to the spot by a phone call reporting an abandoned car.’ He shucked off a shoe. ‘It’s an old trick.’ The second shoe dropped to the floor. ‘They should have known.’ He sounded done in.

‘What will happen?’

‘A round-up of suspects from whom they will try to extract information.’ He twisted round to look at her. ‘It’s depressing. We thought that sort of violence was over in the nineteen nineties and everyone could get on with peace, Italian style.’

‘Not a vendetta, then?’

‘It’s possible.’

She touched his arm. ‘Your lot are OK?’

‘Yes.’ He slid into bed, pulled up the sheet and sighed deeply.

Lottie searched her memory for what she knew about recent Italian history. ‘The bombings in the sixties and seventies? Who was responsible?’

He didn’t answer.

‘Wasn’t the US desperate to stop Italy sliding to the Left?’ He didn’t answer. ‘Tom, I find it very odd that you have been involved.’

He turned away. ‘Can’t talk now.’

Lottie fell asleep with violent images going through her head.

In the morning, she wanted to know the details.

‘Nobody knows anything much at this point.’

‘Except you were summoned to the scene.’

Lottie was brushing her hair and, glancing into the mirror at Tom, caught him unguarded and was surprised by his expression, which lacked his usual affability. ‘I keep thinking about the injured. And the dead.’

His face cleared. ‘It’s bad,’ he said. ‘And brutal.’

When they met again that evening, she had decided not to raise the subject of the bombing but to tackle him on a subject that she was anxious to get settled.

When she agreed to marry Tom, Lottie imposed two conditions – and the one led into the other. First, an overhaul of the apartment’s Neanderthal plumbing. He had been unexpectedly curt. ‘This is an old building. What do you expect?’

‘I expect a working lavatory,’ Lottie replied tartly, recollecting her tricky encounters with the incumbent one. ‘So does everybody else in the world.’

The second was to create a small, urban garden on the balcony. The plumber who had been summoned for a consultation sucked his teeth when she asked for a tap to be installed for the watering and muttered about installing a new set of outside pipes. This would require scaffolding and would be expensive.

Tom said, ‘For God’s sake, can’t we fill the watering can in the kitchen sink?’

But Lottie had become battle-hardened and was prepared. ‘We can’t live in a city like Rome without plants. Or, I can’t.’ She ticked off a list, which included lavender, a lemon tree, herbs, roses.

‘And to think all these years I’ve managed.’ Tom was at his driest.

‘Plants are necessary for a healthy life. Think about eating surrounded by lavender and roses.’

‘I do. I do.’

‘Good. The soul becomes sick without green around it.’

Tom was aghast. ‘I had no idea you were one of those.’ Lottie grinned. ‘OK. Just take pity on the person, almost certainly me, who’ll be carrying the bloody things up the stairs.’

CHAPTER TWO

LOTTIE HAD BEEN SCHEDULED TO TAKE UP HER POST AT THEArchivio Espatriati on return from honeymoon but there was a glitch. The outgoing chief archivist (who, it was rumoured, had links to the government) had been scheduled to retire before Lottie’s arrival and to disappear gracefully to his villa at Tivoli, but was still in post.

‘It’s tricky,’ Lottie messaged Helena and Peter. ‘And complicated in a magical Italian way. It goes something like this … my predecessor has neglected to file tax returns. He can’t get his pension without them. In order to hand them in, he has to be at the tax office in person. There are several tax offices but no one can tell him which one he should go to …’

Both Valerio Gianni, the director, and her predecessor were embarrassed and apologetic. They begged Lottie not to consult her lawyer as ‘all would be arranged senza problemi’. Valerio presented her with a bunch of flowers.

She ignored the request and established contact with her lawyer, Signora Bruni, who could only advise that the process would take time.

An agreement was hammered out. Lottie would be allocated a temporary office, with the understanding she could roam through the archive as part of her preliminary preparations. As soon as the furniture for the office could be arranged, she would start. Valerio Gianni shrugged. ‘Maybe a week, maybe not.’

Tom envied Lottie’s unexpected freedom. ‘This is your chance, Lottie,’ he said. ‘Go and explore. Enjoy. Get to know Rome. Be seduced by her.’ He took her hands in his. ‘Be careful, though. There are no-go areas.’

Having lived in Rome for fifteen years and possessed of a sharp curiosity (‘nosiness’ said his harder-hearted friends), Tom knew a lot about the city and the Romans – her history, her restaurants, feral cats, paintings and traffic bottlenecks.

‘To live da romani,’ he said, ‘is to live fully and sweetly.’

He believed it. He really believed it, and Lottie was halfway to believing it, too.

‘Come with me?’

He wrapped his arms around Lottie. ‘If I can, I will.’

Lottie took to the Roman streets and the tourist buses, and it turned out to be a pilgrimage of discovery – the classical ruin, the elaborate church, the boastful palazzo, the street fountain, the seduction of Roman ice cream, the shops.

‘It’s quite a feat,’ she observed to Tom. ‘Those cabin-sized shops can stuff in amazing amounts of sausage, pasta and cheese.’

It was a similar story at the corners and crossroads, where the kiosks were stacked with postcards and publications with eye-watering headlines. In the mornings, the daily pantomime of traffic trying to squeeze through thoroughfares created originally to take nothing bigger than the average Roman chariot got off to a rip-roaring start and was lent a wilder edge by the anarchic Roman parking habits.

Before long, an unfamiliar, almost dreamy, compliance flooded through Lottie’s veins. Why be in a rush to take up the job? Signora Bruni would conduct negotiations. All would be well.

However, the summons had arrived and Lottie was now walking to the Archivio Espatriati.

Turning left, she encountered a stonemason mending a wall. ‘Tack, tack, tack’ went his hammer. A dog barked, a child cried, ‘Mamma.’ And again, with an irritable longing, ‘Mamma.’

She passed a bakery where a row of family-sized loaves, resembling cushions with rounded edges, were arranged on the shelves. A few doors down, she stopped at the café-bar and ordered a coffee and a pastry and ate and drank while the sun played on her back. It was the time of year when the swifts winged in from Africa; Tom had told her to listen out for their cries.

The ironwork chair left patterns on her thighs. The traffic alternately flowed and snarled; a child ran down the street balancing an ice cream in each hand. It was a combination of the transient with the enduring – and it all could disappear with the snap of a snarky Roman goddess’s fingers.

Her phone rang. Peter.

‘Just checking.’

She laughed delightedly. ‘Hang on.’ She photoed her half-eaten pastry. ‘Sending pic to make you envious.’

‘I feel the drama of the city from here.’

‘Drama was here. A bombing,’ she said. ‘It was horrible, and Tom had to deal with the aftermath.’

‘Is he a Boy Scout, too?’ The lightness of Peter’s tone hinted that his scepticism about Tom was ongoing.

‘Those involved were colleagues.’

There was a small pause.

Pantomime. Noise. Feel. More noise. Ancient stones under her sandalled feet. Toneless and without pulse Rome was not … and would never be. ‘I think I’ll end up being happy here,’ she said.

‘Only think?’

‘I’m sinking into her.’

‘And the rest?’

He meant Tom, the job, the ghost of Clare.

‘All very fine.’

‘Very or very?’

Lottie felt a rush of homesickness and scolded herself. ‘I may love Rome, but I miss you,’ she said.

Later, she crossed the street, dodging a cyclist intent on murder. She stood gazing after the homicidal rider. What if she had been killed like those who had been in the bomb?

Her mood darkened and a shadow cast itself over the scene, and she was reminded of the darker places in any city – its sewers and marshlands. Its tenements. The places, even affluent ones, where screams were not unknown. And the places and times when bombs exploded and extremism thrived.

The Via Giulia had been named after a pope, which Lottie was sorry about. It would have been so much more interesting for it to have been a testament to a Roman matron who had had a wild sex life and a vicious grip on power behind the scenes.

Its surface was cobbled, and substantial pink-, ochre- and yellow-painted buildings rose on either side. She stopped to look at the Mascherone fountain, which was reputed to run with wine at civic celebrations, and at the former jail, now an anti-Mafia headquarters, and spent a moment outside the church of Santa Maria dell’Orazione e Morte, whose funds had been collected in order to bury unclaimed corpses, including those found in the Tiber.

A couple of buildings down from Santa Maria, the burnt-umber Archivio Espatriati rose four storeys high. Like many Roman buildings, it was constructed around a courtyard accessed through an archway, and she stopped to ready herself before she passed under it.

A Paul Cursor, from the Medieval department, had been deputed to give her a tour and to show her to her makeshift office.

Afterwards, they bought coffee and took it up to her office. He seemed embarrassed by Lottie’s predicament. ‘Things can take time here,’ he said.

He told her about the retired American general who had set up the Espatriati. Rattling with medals, the general had turned up in Rome in the early seventies, a trip he declared had been ‘to chase up the memories’. Apparently, these stretched right back to 1948, when he had been in Rome with a mission to hunt down ex-Nazis lying low in the city, waiting for travel permits to be forged in the backstreets to countries willing to offer them sanctuary.

Of middle height and middle-aged, with soft, thinning hair and a terrible haircut, Paul had come across, at first, as nice but a little colourless. But he came to life narrating the story, which Lottie enjoyed relaying to Tom while they ate dinner. ‘The Ratline,’ she told him. ‘It was very efficient. There are rumours that both the Church and the CIA recruited these ex-Nazis and washed their records clean if they agreed to fight Communism.’

Tom helped himself to a glass of wine. ‘I like the sound of Paul. He has a vivid imagination.’

What was not in dispute was that, during the Nazi occupation of Rome, documents, of all denominations and provenances, had been thrown into crates, nailed down and stowed in a cave to the south of the city. Over the years, additional records had been piled in with them, including those of foreign nationals. There they remained, disordered and decaying, until the general rode to the rescue.

An orderly man, as he informed all who would listen, he had been appalled by the predicament of such ‘a trove of intelligence’, and needed – goddammit – to do something about it. His first move was to raise the funds for the establishment and running of a professional archive to house all the papers of British and American ex-pats and to make provision for past, present and future records. Other nationals would have to look after themselves. The funds had been raised – ‘it was surprising how many people could spare a dime’ – and the Archivio Espatriati, a strictly private operation with a mixed staff of Italians, Americans and British, had come to be well regarded and well used.

The building chosen on the Via Giulia had been abandoned since the war. It was easily divided into departments and had the incomparable advantage of a vaulted cellar running the length of the building, which was converted into storage for the archive. Systems had been installed to maintain a cool, stable temperature and to keep the humidity to a minimum.

‘Why would a starred American general concern himself with an archive?’ Lottie asked Tom. ‘And why would anyone give money?’

‘That’s easy. Read the inscription to him over the entrance. And you can bet your life it wasn’t people who coughed up the dimes, it was institutions.’

‘I don’t blame him for craving a touch of immortality.’

Tom placed a hand on her shoulder. It was one of those moments when she was unsure what he intended by the gesture – a manifestation of the areas of uncertainty in an infant marriage. Things unsaid, inflections misinterpreted, intentions unfathomed.

Reaching up, she entwined her fingers in his. ‘That much money …? It’s—’

Tom interrupted her. ‘Could we move to the bedroom?’

He spoke lightly and with anticipation. Lottie was not going to say no but afterwards, half dressed and brushing her hair in the mirror, she wondered if it had been a deliberate ploy? She raised a bare arm and observed (thank goodness) how the flesh under her arm tightened. ‘Were you trying to not answer my question?’

Tom was still prone on the bed. ‘Probably,’ he murmured. ‘You could be a painting by Bonnard. All lush and tremulous.’

The settled light in the room, Tom’s rumpled hair and naked legs, the subdued blue gleam of the coverlet also suggested an artist’s composition.

Lottie smiled at him through the mirror. ‘Back at you.’

The makeshift office at the Espatriati turned out to have a large window, a good-sized desk and a well-used office chair.

The building’s past was obvious in the plaster work and substantial fireplace. Good for the general, she thought, and his craving for a little bit of immortality, although she was still intrigued as to why he would choose an archive as his vehicle. Maybe it had been Mrs General who had been on the case. Maybe it had been she (who had been left behind countless times in the boondocks while Herb or Norm strutted the battlefield) who said, ‘There’s an opportunity here to get your name in lights.’

She unpacked archival polyester pockets and sleeves, plus silver-safe paper for photographs. She held one up between her finger and thumb. Archival records were judged not only as a collection of individual documents but also on their relationship to other records. Which order did they arrive in? Who donated them? Why? These factors were crucial in deciding their significance.

Having stowed the materials, she drank some of the fancy mineral water that had been left on a tray and turned her attention to the documents.

A trestle table ran almost the length of the back wall, positioned away from the direct light, trapping a familiar nosegay of foxed paper, damp cardboard and must. On it was arranged the latest papers to be exhumed from the warehouse.

A temporary label read: British Nationals, 1880–1980: Mortalities: Homicides, Suspected Homicides, Suicides.

The documents had rotted over the years, and their stench grew more marked as the room warmed up. The paradox of decay, Lottie reflected, was that it indicated that life had once been present and it should not be vilified. Decay was a process that worked in the shadowlands before the memory of someone, or something, was extinguished.

Homicides, Suspected Homicides, Suicides …

What must Rome have been like post-war? Smashed and sour with violence and enmity like much of Europe? And later, during the sixties and seventies, when political tensions savaged the country, did it shed its stylishness and atmosphere? They were the decades, Tom had told her, in a tone suggesting deep significance, that had been nicknamed ‘The Years of Lead’.

‘An odd term,’ she’d commented.

‘It refers to the huge number of shootings. At times, it was bad. Really bad.’

‘Fascinating, isn’t it, how far belief can push you?’

‘Well,’ Tom had said, ‘all of us are guilty one way or another of small fanaticisms.’

Curious, Lottie had done some research. In 1978, the political divisions and social tensions had culminated in the kidnapping and murder of the former Prime Minister, Aldo Moro, a dominant politician in what was in practice a one-party state. Some called him the ‘master-weaver’ of Italian politics. The year after his death – 1979 – had been even worse, with over six hundred attacks.

Italians had enjoyed many freedoms, including press freedom, but when they voted it was known that it could only have one result: victory for the Christian Democrats; legitimate opposition, such as the Communist Party, was denied any power.

She had discussed it with Tom. ‘But if the Socialists and Communists had made real headway in an election …?’

His answer had been guarded. ‘It’s likely that Washington would never have allowed it. During the Cold War, no western European country could display even a residual loyalty to Moscow.’

‘So,’ Lottie had said, ‘the realities of power.’

Tom was always pragmatic. ‘In its way, it worked in Italy. The Communists ran some of the regions and did so efficiently. Everyone got along until Moro tried to make an agreement with the Communists by which they would support the government in a national crisis. No one liked that.’

Moro wrote to his wife from his captivity and castigated the politicians and power brokers who had failed to come to his aid – including the Holy See, which refused to negotiate with terrorists. In a final paragraph of his last letter, he wrote of ‘the inexpressible joy you gave me during my life, of the child I took such pleasure in watching and whom I shall watch to the last …’

Lottie had found it difficult to read. ‘It doesn’t matter who you are, does it? It’s your family you think about at the end and …’

‘And?’

‘Very often your debts.’

Tom had laughed.

Dust spilled from the papers on the table’s surface. Unless unavoidable, materials must never be directly handled. Lottie unpacked her hand-held vacuum cleaner and siphoned it up.

The first task – she glanced at the sun shining outside the window – was to create the Item List as defined by international standards, which involved Reference Codes and precise descriptions.

Allocating the papers a code, she wrote Mortalities: British Nationals, 1880–1980 on a label, dated it and began.

At the start, she had not understood what had drawn her to becoming an archivist. Older and wiser, she realised that unconscious wishes operated cunningly with the conscious will: she had chosen the profession because she needed its order and rules and it was a way of engaging with humanity without meeting it.

How ironic, then, that this paper engagement turned out to be far from arid and distanced but a daily confrontation with every shade of emotion and behaviour. The documents were a portal into lives and thoughts. In them, Lottie encountered the cruel, the innovative, the violent, passionate, duplicitous, bigoted, corrupt, the altruistic and the loving.

She had learned to interrogate those voices. Who are you? Are you a woman observing from the sidelines? Or are you the man fired up by his religion to the exclusion of sense? Did you live well or badly? Perhaps you are a corrupt leader or a worker who died from careless employer practices?

What people wrote could be quite different from what they thought. What they said could be far from the truth. What they believed on paper could be the reverse of the slippery ambitions in their souls.

Mortalities. She bent over the papers to take a closer look. A puff of dust sifted on to the bench and she wiped it away.

A cursory examination revealed that a percentage of material was too damaged by water and fire for redemption. Isolated words loomed up from the fragments … ‘amore’, ‘blood’, ‘political’.

They would be collected up and a decision would be taken later as to their disposal.

Back at her desk, she checked the summary of the file’s contents. They included records of homicide cases – sometimes the originals, sometimes copies of what was in the police files. Documentation of circumstantial and anecdotal evidence was also included.

She began.

Shimmering below the statistics and stark reports, a picture emerged of an accomplished and fascinating seductress, aka Rome, whose riches and pleasures could be overwhelming and occasionally fatal.

British Nationals died from natural causes over the decades but, decoding the figures for the early twentieth century, there was a case to be made of ‘come to Rome and die’. Some were claimed by ‘Pontine Fever’ (almost certainly malaria), others had swum ill-advisedly in the Tiber and contracted virulent bacterial infections. There was substantial turn-of-the-century mortality from TB, measles and polio. Later on, the death rate levelled, only to go haywire during the Second World War, midway through which the records went blank.

During the late forties and fifties, the murder rate for British and American nationals picked up. A toxic brew of revenge, vendetta and privation in a feral, post-war vacuum? She checked online to see if there were papers on the subject, and ordered up a promising-sounding one by a professor of epidemiology.

In 1952, the British husband of an American film star working at Cinecittà had been found suffocated by his own socks in a hotel bathroom and his male lover had been strangled with a dressing-gown cord. His widow had immediately flown home, leaving a multimillion-dollar film in limbo. Later sightings of her reported – in the immortal words of Oscar Wilde – that her dark hair ‘had turned gold with grief’.

In 1960, Carol Enderby was driven into a tree by her jealous Italian lover. Both died.

Lottie wrote: Carol Enderby. 1 Folder. Papers and loose photographs.

Then there was the fashion designer who had been found suffocated in the therapeutic mud in the beauty parlour that she frequented … and a couple of so-called American businessmen who had each been taken out by a single shot to the head in the early seventies. Four Folders. Damaged papers. Possible disposal.

By the end of the day, she had done an initial survey and categorisation of the material to be allocated to the respective departments.

Two large boxes remained outstanding. A temporary label had been attached to both: Nina Maria Lawrence, 1940–78. No known contacts. No known issue. No claimants.

The information checked Lottie. It was bald and unforgiving. To have no one to attend to matters after your death suggested that you had had no one during your life. Therein lay tragedy? Abandonment? Neglect? A hatred of other humans? Terrible poverty and exile? It was a sad dereliction and she was sorry for it.

She thought of her new life, and of Tom, with relief.

Paul Cursor came down from his office on the third floor with a package. ‘I’m interrupting …’

She shook her head.

‘I hope you don’t object.’ Paul was a little hesitant, which, after a second or two, she put down to good manners rather than nervousness.

Lottie dusted her fingers. ‘I’m sure I won’t.’

‘We did a quick check on some of the material before you arrived.’ He pointed to the first Nina Lawrence box. ‘That one contained what might be a valuable painting from a manuscript.’

‘The woman who appears to have had no one?’ Lottie was both surprised and intrigued.

‘Seems so. It’s been put into a frame for protection. I took the liberty of booking an appointment with Gabriele Ricci for you to check it out with him.’ He handed over an additional folder. ‘This is from a colleague. Take a look if you wish. It’s about Bonnie Prince Charlie’s daughter. Rather poignant. She stuck by him to the end, despite the drink and his cruelty to her. Ricci’s been briefed on it.’ Again the good-mannered hesitation. ‘Ten o’clock tomorrow,’ he said.

She opened the folder. The letter requiring conservation was safely encased in acid-free paper. There was also a second document. ‘And this one?’

Paul was almost at the door and turned back, features taut with concern. ‘Apologies, I forgot. It had got attached to the painting and is to go back into the Lawrence box.’

Dated 12 January 1976, it was a typed receipt written on crested writing paper.

Palacrino Garden

Commission to landscape and plant a garden of approx. 2 acres. Detailed drawings to be submitted.

Overall concept: to create ‘garden rooms’

1) English garden to include hollyhocks and roses

2) Walled medieval one to include regularly spaced fruit trees (apricots and pomegranates), box hedging and lavender

3) A cypress avenue

4) Lemon trees in terracotta pots

5) Travertine paving

Paid to Nina Lawrence the sum of 10 thousand lire for consultation.