Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

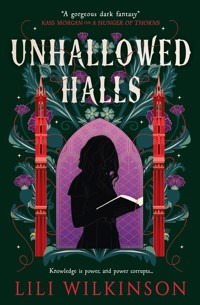

An American teenager joins an exclusive boarding school hidden deep in the Scottish countryside. New friendships blossom, but not everything is as it appears... Drawing on ancient Gaelic myth, this compulsively readable dark academia fantasy is full of twists, turns and heartstopping betrayals, perfect for fans of Ninth House and The Atlas Six. Page Whittaker has always been an outcast. And after the deadly incident that destroyed her single friendship at her old school, she needs a fresh start. When she receives a scholarship offer from Agathion College, an elite boarding school folded deep within the moors of Scotland, she doesn't even consider turning it down. Agathion is everything Page has ever wanted: a safe haven full of dusty books, steaming cups of tea and rigorous intellectual debate. For the first time in her life, Page has almost managed to make a close group of friends. Cyrus, Ren, Gideon, Lacey and Oak help her feel at home in Agathion's halls—the only problem is, they're all keeping secrets from her. It seems Page's perfect new school has dark roots—roots that stretch back to its crooked foundation, and an ancient clandestine society. Page quickly learns that not everyone at Agathion is who they say they are. Least of all her new friends.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 561

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

1 September 15

2 September 16

3 September 16

4 September 16

5 September 20

6 September 20

7 September 21

8 October 21

9 October 26

10 October 26

11 October 27

12 October 28

13 October 30

14 October 30

15 October 30

16 October 31

17 October 31

18 October 31

19 November 1

20 November 1

21 November 3

22 November 3

23 November 3

24 November 3

25 November 3

26 November 3

27 November 4

Acknowledgments

About the Author

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Unhallowed Halls

Print edition ISBN: 9781835413999

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835414002

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: February 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Lili Wilkinson 2025

Lili Wilkinson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP

eucomply OÜ Pärnu mnt 139b-14 11317

Tallinn, Estonia

+3375690241

Typeset in Adobe Caslon Pro 10.5/14pt.

For Michael, who has a knack for demons

I intend to speak of forms changed into new entities.

—OVID,METAMORPHOSES

For before this I was born once a boy, and a maiden, and a plant, and a bird, and a darting fish in the sea.

—EMPEDOCLES

For all things turn to barrenness

In the dim glass the demons hold,

The glass of outer weariness,

Made when God slept in times of old.

—WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS,“THE TWO TREES”

What did you do?”

Streaks of rain glitter on the windows as the train races through unending bleak moorland. I didn’t think the journey would take so long—night has fallen and all I can see past the raindrops are shadows, deep and full of secrets.

The carriage is nearly empty—a woman bent over a laptop, fingers tapping a staccato counterpoint to the steady rhythm of the train. A man asleep, his head against the window. Three teenage girls, their feet on the seats. One of them stares at me from under false eyelashes, her question hanging in the air.

“What did you do?”

I always imagined British people would have posh accents, but this girl is proving me wrong. I can smell hairspray and spearmint and cherry lip gloss.

Since they got on a few stops ago, the girls have filled the carriage with their presence. Their shrieks of laughter, their cursing, the snap of their gum. I feel a stab of jealousy at their ease with each other, with the world. They inhabit their bodies so comfortably, propelling themselves through time and space with such confidence. I can’t imagine how it must feel.

The girl is still waiting for an answer, but I don’t know what to say. I don’t know what I did.

She stands and approaches me, swaying with the movement of the train.

She’s wearing an outfit that is simultaneously casual yet completely over-the-top—camo-print tracksuit bottoms and a lurid green tube top.

Her makeup is thick and applied with painterly precision, her skin unnaturally orange, her brows like perfectly sculpted punctuation marks.

She nods down at the brochure poking out of my battered copy of Middlemarch. I’ve been using it as a bookmark.

“That school is for posh fuckups,” she says. “So why are you going? Drugs? Stealing? Did you get into fights?”

I follow her gaze back down to the Agathion College brochure. Images of arched windows and turreted spires surrounded by romantic moorland grace the glossy pages. Blue-gray stone walls, wreathed in creeping ivy. Serious-looking students in wool kilts and tweed blazers bent over ancient books. When the brochure arrived in the mail, along with a full scholarship offer, it seemed too good to be true. It still does. I imagine myself there, surrounded by books and knowledge and history. I’ll wander the moors like Catherine in Wuthering Heights and curl up in the huge stone castle with a steaming cup of tea to read Dickens and Austen and my beloved Shakespeare.

A life of the mind.

Maybe sometimes I’ll engage with the other students, debating poetry or philosophy. Not friends, because I’m not doing that again. Colleagues, perhaps. Intellectual peers. Previous Agathion students have gone on to become famous politicians, writers, and artists, according to the brochure. There’s even one former British prime minister who attended.

“Bet she killed someone,” says another one of the girls, whose long fingernails are pointed slashes of teal and gold. “She looks the type.”

Do I?

I stuff the book and brochure into my backpack. Out of the corner of my eye, I see Tube Top Girl recoil slightly, and I know she’s noticed my hands.

“Come on,” the girl with the long fingernails says. “Before she puts a spell on you.”

I let my gaze drift up to meet Tube Top Girl’s, and see the faintest hint of fear there, behind her enormous false lashes and brash confidence. My hands curl in on themselves, obscuring my shiny pink palms.

The girl shrugs and returns to her friends.

My parents offered to come with me, but I insisted on traveling by myself. I wanted to get on board that plane and never look back. I wanted to get as far away from Lakeland, Florida, as I possibly could. From the smell of burning flesh and jasmine, and the sound of Cassidy screaming.

Agathion feels like the only way out.

A place where I can learn to control myself.

I can feel the train start to slow. We’re nearly there.

I feel a twinge in my abdomen—an echo of the deep dragging pain that is so familiar to me, and my pulse quickens.

Not now.

But, I remind myself, I only just had my period. This is nerves.

I stand and head down the swaying carriage to the luggage rack. I have to pass the three girls, who look up at me as I walk.

“Loosen up a bit, hey?” the bold girl says. “Let your freak flag fly.”

My cheeks feel hot and sweat prickles down my back. I am frozen in place, pinned by the casual, insolent gaze of this girl who I’ve never met before and will never see again. She doesn’t matter, so why can’t I move or speak? The dragging sensation in my belly intensifies.

Someone screams, and I’m back at St. Catherine’s, my hands burning and my lungs filling with acrid smoke.

But it isn’t Cassidy screaming. It’s just the squealing of brakes as the train slows. I’m thrown forward against the bold girl as we shudder to a halt.

“Hey,” she says, laughing. “Buy me dinner first!”

Her skin is smooth against mine; the scent of her lip gloss is overpowering.

I scramble to my feet and away to the luggage rack.

I can’t miss my stop.

I can’t.

The doors hiss open, and I am shaking with panic. I grab the handle of my suitcase and yank, but it’s stuck. I pull and pull, but it won’t budge. I try pushing instead, trying to jostle it into a better position, but that only seems to make the problem worse. I kick it.

Outside, the train’s whistle blows.

I’m out of time.

“Do you need a hand?” asks the bold girl.

It’s too late. The train is about to leave the station.

And I realize that whatever’s in that suitcase—I don’t need it.

I’m coming to Agathion to live a life of the mind.

I have everything I need.

“Weirdo,” mutters the girl, turning back to her friends.

I leave my suitcase behind and step off the train.

The platform is sparse and entirely empty. The air is cold—much colder than I had expected. I breathe deeply until my lungs ache, and I love the feeling. Icy drizzle caresses my skin, and I turn my face up to it.

I’m here. I’m really here.

A fluorescent light spits and hums next to a weathered sign reading RANNOCH MOOR. The train pulls away behind me, disappearing into the darkness. For a moment I panic, thinking I’ve gotten off at the wrong station. But I checked a million times. I’ve rehearsed this journey in my head over and over.

There’s a ticket office, but it doesn’t look like it’s been open for years. I step through the gate, and peer into the darkness. I can hear something huffing out there. Some kind of animal—barrel-chested and hulking.

A hazy orange glow emanates from behind the ticket office. I head toward it, past an ancient-looking pay phone and down a set of stone steps, finding myself on a worn dirt road.

Before me is a lamp, burning golden, affixed to, impossibly, a horse and buggy—the kind you might find in a Regency novel. The horse is black and broad, its head bowed, its breath blowing out in steaming clouds. It shifts from one foot to another as I approach, and it nickers softly.

Perched in the driver’s seat, reins slack in one leather-gloved hand and the other holding an umbrella, is a tall, thin woman wearing a dark wool coat. Her steel-colored hair is pulled back in a rather severe bun. Dark eyes turn to me, sharp as struck flint.

“Page Whittaker?” She’s Scottish, her accent elegant and polished.

I nod.

“I am Magistra Hewitt. I’ll be your tutor during your time at Agathion.”

According to my internet sleuthing, every student at Agathion is assigned a tutor, who acts as a mentor and guide. There are regular teachers, too, but it’s the tutors who live on campus with us and provide the unique experience of Agathion.

I look up at this woman, and I see intelligence in her eyes and the worn lines of her face. She seems a little terrifying, but I’ll take it over the limp sacks of apathy that passed for teachers back home, who could do nothing for me other than shrug and shake their heads.

Magistra Hewitt looks down her strikingly assertive nose at me. Her eyebrows seem permanently raised in a manner that makes me feel like I’m being assessed.

“You have no luggage? Good.”

She tilts her head at the bench next to her, and I scramble up, feeling awkward and entirely out of place in my jeans and puffer jacket next to her simple elegance. She adjusts her grip on the umbrella so it covers both of us.

“One of the foundational principles of Agathion is that you come as supplicants, like the akousmatikoi of Pythagoras, who shed their hair, their clothes, and their names, and spent five years in total silence as a form of initiation.”

Without thinking, I raise a hand to my ponytail, and she smiles a thin-lipped smile.

“Fear not, Miss Whittaker. You may keep your hair. And your name, for that matter. And we will not require five years of silence.” She hesitates, side-eying my puffer. “You will be provided with a uniform, of course. You bring no baggage, figurative or literal. No technology. These things link us to the material world, and Agathion is a school for the mind.”

Yes. That’s why I’m here.

“‘’Tis the mind that makes the body rich,’” I quote. “‘And as the sun breaks through the darkest clouds, so honor peereth in the meanest habit.’”

If the magistra is impressed by my knowledge of Shakespeare, she shows no sign of it. Instead, she twitches the reins, and the horse starts to walk forward. I shrug my backpack off and hold it in my lap. My new tutor eyes it distastefully.

The horse pulls us into the darkness as rain patters gently on the umbrella like a caress. The lantern hanging from the side of the buggy casts a dim golden glow around us, but beyond the horse’s nose is nothing but black. I wonder how it knows to stay on the road. Has it done this trip many times?

“Ms. Hewitt?” I ask tentatively.

“Magistra Hewitt,” she corrects, but not unkindly.

“Magistra Hewitt. Does everyone get picked up in a horse and buggy?”

She hesitates again before replying. “We have learned that keeping a car on campus overnight can be rather more temptation than some of our students are able to resist.”

I think of the girl on the train.

That school is for posh fuckups.

“Of course, the day teachers bring their own vehicles,” she adds as an afterthought, like she forgot there were day teachers. “But they leave midafternoon, and the rest of the staff depart after dinner.”

“But not the magisters?” I ask.

She shakes her head. “We are your mentors,” she says. “We live here alongside you, to guide you at all times.”

I hope she doesn’t mean literally alongside us. I don’t want to share a bedroom with a teacher.

“Agathion College is located on the Great Moor of Rannoch,” Magistra Hewitt continues. “There is evidence that it has been a home for unwanted or troubled children for more than a thousand years. However, it was in the eighteenth century that we transformed the school into an exclusive haven for gifted young people. A sanctuary for those who live in the realm of the mind, who seek to see past the shadows and distractions of base feelings, and glimpse the true secrets of the universe.”

There’s a note of pride in her voice, like she was personally responsible for this shift in educational philosophy.

I breathe in the rich scent of the moor, earthy and botanical. There’s a faint edge of woodsmoke as well, sweet as incense. It smells glorious.

“You’re lucky to be here, Miss Whittaker,” Magistra Hewitt says. “We don’t often offer scholarships.”

I want to ask Why me? How did they even know about me? Did they hear about what happened at St. Catherine’s?

“Try not to feel intimidated by the backgrounds of the other students. At Agathion, all are equal. Bloodline, wealth, class—these things cease to exist when you cross the threshold. I’m sure you’ll make friends.”

Unlikely, but that’s not why I’m here.

“You’ll have questions, I’m sure,” Magistra Hewitt continues. “I ask that you save them for our first meeting.”

I nod again.

“You’ve missed dinner,” Magistra Hewitt continues. “But a tray has been sent up to your room. We’ll meet in a few days, after you’ve settled in.”

I know from my obsessive googling that Agathion doesn’t have set terms or holidays—students arrive and stay until they graduate. I’m still not really sure what that means—is there an exam or test that has to be passed, or is it something the magisters decide? Some alumni seem to graduate after only six months, but I’ve read about others who stay for three or four years—like superstar violinist Ryu Yasuda, who was an Agathion student in the 2000s.

The horse speeds up a little as the lantern’s dim yellow light falls upon a huge set of gates, black iron wrought in heavy bars, topped with a row of wickedly sharp-looking spikes. The gates are open, and the horse’s gait seems to lighten, as if it is anticipating a nice dry stable and bucket of oats.

The scent of woodsmoke grows suddenly strong and pungent as I get my first glimpse of Agathion, looming magnificent and haughty from the darkness like a castle from a fairy tale.

My extensive research means I already know that Agathion has been a school since the mid-1700s. The hill where the school sits has been inhabited since before the Romans invaded Britain, according to archeological records. I know that there is a small farm that raises pigs, ducks, and chickens, as well as growing many fruits and vegetables.

But the facts I’ve ingested from brochures and websites don’t come close to actually being here. Now I really see the exceptional grandeur of Agathion. The embellished moldings and plasterwork. The turrets and spires, thrusting sharply into the night sky. The grotesquerie of the gargoyles that spout inky rainwater from where they crouch on the edge of the slate-tiled roof. The central tower, tall and proud. Wet stone glistens darkly, and shadows gather at the edges of the building where golden light that spills from the narrow, arched windows cannot reach. The air is cold and rarified, scented with smoke and damp earth.

I feel like Catherine Morland arriving at Northanger Abbey. Or Jane Eyre approaching Thornfield Hall.

It feels right.

Magistra Hewitt gets down from the buggy, every movement controlled and elegant.

It’s only been twenty minutes or so, but I already worship her. I swing my backpack over my shoulder and stand to dismount.

“Leave it,” says Magistra Hewitt without looking over her shoulder.

I hesitate. My phone is in that bag. I promised I’d call my mother once I arrived safely. My copy of Middlemarch. A notebook. Pens. My shower caddy, containing a toothbrush, deodorant, moisturizer, and several packets of the little white pills that are the only thing that can take the edge off my period pain. The magistra doesn’t look back as she strides across the courtyard to the main door of Agathion.

I leave the backpack in the buggy and scramble down, hurrying after her.

Gravel crunches under my feet. I can barely feel my hands, and my nose is dripping from the cold. But I don’t care.

I’m here.

Magistra Hewitt’s wool coat flares out behind her as she climbs the broad steps that lead to the door, and I see her leather boots and immaculately tailored black trousers. She pauses so I can catch up.

The door is massive—ancient-looking wood more than double my own height. In the center is a wooden shield bearing Agathion’s crest—a gold cup with a sword before it, a red ribbon swirling around them both. Beneath this is carved the school’s motto—ANIMUSSUPRA CORPUS.

Mind over body.

It’s exactly what I need.

“Welcome to Agathion College,” Magistra Hewitt declares, and pushes the door open with a grand sweep of her arm.

A noise drifts out from inside—the pounding of feet and . . .

Screaming.

And I’m back there again, where I always end up. The wilderness behind the gym at St. Catherine’s, my hands burning, my lungs full of smoke and jasmine.

Staring at Cassidy, who won’t stop screaming, her gaze fixed on the blackened scorched earth.

My vision blurs and I’m in the real world once more. I get a glimpse of a grand hall beyond the door—polished marble floors and golden light spilling onto wood-paneled walls. A huge sweep of staircase rising upward, enclosed with a carved wooden banister. Enormous, gilt-edged paintings and hanging tapestries.

And screaming.

I clench my fists to stop myself from clapping my hands over my ears.

Why won’t it stop?

Magistra Hewitt will think I’m broken. She might even send me home. I have to keep it together.

But Magistra Hewitt has frozen in the doorway, her shoulders stiff.

The screaming is getting louder, and I contemplate the possibility that it isn’t in my head this time. It’s high and panicked and ragged and . . . not human. It sounds almost metallic, like the grinding of metal on stone.

It’s joined by a kind of shuddering, galloping sound, like an irregular drum underneath the screaming. The stone floor beneath me vibrates.

Magistra Hewitt suddenly leaps to the side as a . . . creature . . . comes charging across the foyer and sweeps me off my feet. It seems huge and monstrous, all lumpen gray flesh and bristles and yellowing, cracked teeth in a wet mouth that is wide and screaming, screaming, screaming. Black, glittering eyes are fixed on me, and I see nothing but rage.

Whatever this thing is, it’s trying to kill me.

I try to roll away from it, but it tangles me up in its filthy legs, its cloven hoofs striking dully on the marble floor. My cheek is pressed against the stone threshold, and dimly I notice the marks carved into it. The script is unfamiliar, runic, the lines worn down over time and black with grit.

“Get off her, you old fool.”

Hands scoop up under my arms and drag me to the side, sliding over the marble away from the creature, and as it slips and scrambles to the threshold, I finally see it for what it is.

A pig.

It’s a pig.

A huge one—it’d be twice my weight easily or more. Gray and bristled and fleshy, with muddied legs and an ugly face, all thrusting snout and tiny dark eyes.

“Get out,” Magistra Hewitt says to the pig. Her voice is calm but firm. “You’re embarrassing yourself.”

The pig lets out another grinding, bloodcurdling scream, and then leaps over the threshold and crunches across the gravel driveway, vanishing into the darkness. I hear the thundering of hooves on turf, then it is gone.

Magistra Hewitt leans down and helps me to my feet. “Are you hurt?”

My heart is pounding so fast I’m afraid it is going to burst from my chest. I clench and unclench my shaking hands to try and regain control.

“Miss Whittaker? Can you hear me?”

“I—I’m okay.”

Behind Magistra Hewitt, I see a boy appear, skidding around the corner from some unseen corridor, his eyes widening when he sees us.

The boy is absurdly handsome—golden brown skin, aristocratically hooked nose, gently curling dark hair, and warm eyes fringed with thick lashes. He’s exactly the right size and shape—like someone was asked to make a perfect human. His Agathion uniform fits him like it’s been tailored—white shirt, dark gray wool trousers, and a brown tweed blazer with brass buttons. His burgundy tie is askew in a deliberately casual manner. He oozes charm in a way that makes me want to crawl under something dark and damp and stay there forever. This boy is a totally different species to me.

He straightens his tie just as Magistra Hewitt turns around.

“Mister Alimardani,” she says in a clipped tone. “What on earth is going on?”

The boy spreads his hands and shrugs. The gesture is understated, but the boy moves with a fluid grace. I’ve never seen someone so confident in their skin before—he makes those bold girls on the train look like . . . well, like me.

“Old Toby must have escaped from the farm, Magistra,” he says, his voice as smooth and confident as the rest of him. “I was studying in the library when I heard the commotion.”

She stares at him for a considerable while, as if she’s waiting for him to confess something. He gazes back, totally unconcerned, his mouth curved in a nonchalant smile.

Magistra Hewitt lets out a small, frustrated sigh. “This is Page Whittaker,” she says curtly, indicating me with a nod of her head. “Take her upstairs. Room 207.”

“Of course, Magistra.”

Magistra Hewitt goes sweeping out the front door and disappears into the darkness. I wonder if she’s going to go and catch the pig with her bare hands. Or if the pig will simply obey her command to return to its sty. She seems pretty persuasive.

The boy reaches out a hand for me to shake, his eyes warm. “Nice to meet you. I’m Cyrus. Named after Cyrus the Great, and while I’m not a particularly skilled military leader, nor am I the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, I am, like my namesake, pretty great.”

My own hands are still trembling with adrenaline, but I’ve automatically extended one to be shaken before I remember the scars on my palms. I wait for him to flinch, for his eyes to take on that cast of fear and disgust that I saw in Tube Top Girl’s. But his expression doesn’t change. Cyrus looks like he’s been shaking hands his whole life. His grip is firm and confident but not overpowering. He grins at me.

“Bit of a dramatic start to your first night here,” he observes. “Are you okay?”

I nod. I know I should say something, but I’m out of practice. Not that I was ever particularly good at talking to other young people. Or anyone, really.

Especially not boys like him. Boys who seem like actual princes.

“Old Toby is our school mascot,” he explains. “He’s a cheeky bugger, but usually pretty harmless. I’ve never seen him like that before. He really went for you.”

Cyrus is gazing thoughtfully at me, as if trying to figure out exactly what it is about me that would cause a giant pig to go into a frenzy. I see the wet mouth again. The cracked tusks and the tiny black eyes. Cyrus sees me shudder and chuckles.

“I’m sure you’ll come to like him.”

His accent is unfamiliar to me. Posh British but with something else that elongates his vowel sounds and clips his consonants.

He leads me past the grand staircase, outside again, and into a covered walkway that runs around the edge of a central courtyard. Unfamiliar shapes loom in the darkness, glistening with rain. Trees, maybe, or statues.

A faint whisper tickles my ear, and I spin around, but there’s nobody here except me and Cyrus. I shiver. The courtyard is large—the glow from the surrounding windows doesn’t reach the center of it.

“This is the forum,” Cyrus says. “Everyone eats lunch here, unless it’s raining. We’ve just come from the South Wing, which is the kitchen and the dining hall. Student dorms are the East Wing, the library and classrooms are to the North. The West Wing is where the magisters have their offices and living quarters.”

He turns without waiting for a response, and we go back the way we came. I follow him up the grand staircase. Up close, I can see that everything isn’t quite as opulent as it first appeared. Or at least, not anymore. There is dust in the corners. The gilt picture frames are tarnished, and there are moth holes and worn patches in the tapestries. But it doesn’t feel neglected. Just comfortably lived-in. The staircase is the same blue-gray stone as the walls, each indented in the middle, where feet have been treading every day for hundreds of years.

And now my feet join them. My sneakers feel very out of place here, and I wonder when I’ll get my own brown leather shoes and tweed blazer.

The grand staircase opens into a wide corridor, carpeted in worn crimson. Windows along one side look out over the courtyard—the forum, Cyrus called it. I can’t wait to see it in the daylight—all this darkness is giving me the creeps. The corridor is unheated and smells damp and old. I hope the bedrooms are warmer. Cyrus leads me past a few closed rooms, and then up another smaller staircase, this one made of dark polished timber that creaks under our footsteps.

“The main building is four floors, but a lot of it is empty—there’s less than a hundred students. Is Hewitt your magistra?”

He doesn’t turn to look back at me when he asks this, so I have to answer with my voice.

“Yes.”

Great work, Page. Very good talking.

Cyrus pauses and turns to face me. “So you do talk. I wondered. Sometimes people don’t, when they get here.”

I feel my cheeks get hot, and I imagine what it must be like to have someone like Cyrus as a friend. He seems kind. Open. He’s probably funny.

But I’m not here to make friends.

“American?” he guesses.

“How can you tell?” I ask, my accent giving me away.

“A vibe.”

He says it in a way that makes me unsure if it’s a good vibe.

“Look,” Cyrus says, taking a step toward me. I smell sandalwood and a hint of rose water. “It’s scary. I get it. Starting at a new school, especially one like this. But you’ll like it here, I can tell. Just . . .” He hesitates.

“Just what?”

“Be careful about what you tell her. Hewitt. And the other magisters.”

His tone is serious, and I’m imagining all sorts of horrors—there are plenty of online forums about exclusive boarding schools, full of dark stories of abuse and cruelty. I’ve never seen Agathion mentioned on those forums, but that doesn’t mean nothing bad happens here.

I know what teachers are capable of.

For a moment I think Cyrus is going to say something else, but a door slams somewhere down the hallway, and Cyrus shakes his head and smiles.

“You must be tired,” he says.

We emerge in a corridor studded with wooden doors, each one affixed with a brass number.

“Here’s you,” he says, opening a door. “There are no locks—we don’t really have any possessions, so nothing to steal. But make sure you knock before going into anyone else’s room. Boys are on the next floor up—Agathion talks a lot of talk about being enlightened, but they also love to enforce a binary.”

He ushers me into the room.

“Bathrooms are down the hall. Breakfast is served between seven and seven-thirty. Someone will give you a copy of your timetable.”

“Thank you,” I manage.

“And, hey.” Cyrus leans forward conspiratorially. “Don’t be like Alexander. But don’t be late for breakfast, either.”

I open my mouth to ask who Alexander is, but Cyrus just taps his nose, then turns with the grace of a dancer and saunters away.

I close the door, noticing more carved runic marks on the doorframe, then turn to look at my room.

It’s small, with a low, heavy-beamed ceiling and a slanting dormer window. Outside all I can see is raindrops and blackness. The damp chill hangs in the air here, too.

Most of the room is taken up by the bed, an impressive carved wooden structure with a velvet-lined canopy that has seen better days. There are moth holes in everything, which explains the strong odor of camphor. At least the bed itself is neatly made, with crisp white sheets and thick wool blankets. I hope they’ll be thick enough. It’s freezing in here.

A narrow door reveals a built-in wardrobe containing my Agathion uniform—tweed blazer, white shirt, burgundy tie, and a choice between wool pants or a pleated skirt. There’s also a knitted sweater and a cardigan in soft scarlet lambswool. Brown leather shoes with brass buckles. A chest of drawers contains underwear, bras, white socks, a white nightgown, and soft flannel pajamas. Two towels are neatly folded on a shelf, and a cloudy, tarnished mirror is attached to the inside of the cupboard door. The scent of camphor in the cupboard is so strong it makes my eyes water.

I have a bedside table with a brass lamp and an old-fashioned alarm clock. I open a drawer to see a small leather case containing a toothbrush, hairbrush, and a selection of toiletries in little glass bottles that make them look like vintage apothecary supplies. I find hair ties and burgundy ribbons, as well as a discreet pouch for pads and tampons.

A small wooden desk sits against one wall with a simple chair. A tray on the desk, covered with a silver cloche. I lift the cloche and see a bowl of soup, with a pale bread roll and pat of butter. My stomach growls, but I’m not done exploring.

There’s a stack of blank notebooks on the desk—clothbound in scarlet and burgundy, with thick, textured pages. In a drawer I find pencils and a black fountain pen, its silver nib sharp as a knife. I pick it up and examine it—I’ve never used one before. There are pots of ink in the drawer as well. A leather satchel hangs from a hook on the back of the door.

I imagine myself up here, all wool, tweed, and leather, surrounded by great works of literature, scratching notes with my fountain pen. It feels too romantic to be real.

I open the window and breathe in the icy night air until my lungs ache.

The soup has been there for a while and is barely warm. It’s oversalted and has a strange aftertaste, botanical and sharp.

Voices murmur from the room next door to mine, and thumps sound from overhead.

I finish the soup, suddenly overcome with weariness. It’s been a big day.

I pull on the pajamas and climb into bed, then get up again and add a cardigan and two pairs of socks.

I’m not sure if I’ll ever be warm again.

I wake to find a knife on my pillow.

It’s like a miniature sword, the same shape as the one on the Agathion crest, with a ring on the pommel.

It wasn’t there when I fell asleep.

The blade looks old, pitted, and scratched.

It feels like a warning. I sit up, and discover that the knife is the least of my problems.

My bed has been transformed into a cage. Spider-thin thread, the color of dried blood, is strung around the canopy in the most intricate of cat’s cradles, lines crisscrossing and intersecting to form stars, circles, and pinwheels. It’s so dense that I can barely see beyond it.

Whoever did this must have been in my room for a long time. How did I not wake up?

The sharp botanical taste of the soup is still in the back of my throat.

Was I drugged?

My stomach churns at the thought of it. Is this a prank? Or a test?

The threads are wound around the four posts of the bed and affixed to the pegs that line the top and bottom of the bed. I realize where I’ve seen pegs like those before.

This bed is repurposed. It was once a loom.

I reach out a finger and touch a thread. It’s taut and strong but so fine I can barely see each individual line.

Through the thick web, I see the old-fashioned alarm clock on my bedside table.

It’s ten past seven.

I’ve overslept. I never oversleep.

Breakfast has already started.

My chest feels tight. My hands are clammy.

None of my Agathion research mentioned anything like this.

I really need to pee.

I pick up the knife and am about to slash through the threads, when Cyrus’s voice sounds in my head.

Don’t be like Alexander. But don’t be late for breakfast, either.

I liked Greek mythology when I was a kid. All the stories of fickle gods throwing tantrums and turning people into things. But the history of ancient Greece and ancient Greek philosophy —well, I’m no expert, unless there’s a Shakespeare play about it, like Troilus and Cressida or Timon of Athens. Still, even I know about Alexander the Great cutting the Gordian knot.

There was an oxcart hitched to a post with an intricate knot. An oracle foretold that whoever could undo the knot would rule Asia. Nobody could do it, and the knot stayed there for more than a thousand years, until Alexander the Great arrived in town and slashed the knot right through the middle with his sword, freeing the cart.

Don’t be like Alexander.

It is a test, then.

I don’t cut the thread.

I wonder if I can stretch it—work a hole into the pattern that’s big enough for me to climb out.

But this seems impossible. The thread is wound tight and very fine. Any attempt to stretch it will cause it to break, and surely snapping the thread is the same as cutting it.

Maybe I can unravel it. I spend a moment searching the red silk for a loose end that I can pull. But there is so much of it. It would take hours to wind them all away so I can escape, and Cyrus also warned me not to be late for breakfast.

Be logical, Page.

I can’t break the thread. But maybe I can move it.

I stand up and examine the pegs that run along the edge of the canopy. They’re made from wooden dowels, each one inserted into a little hole drilled into the canopy frame. There are hundreds of them, but I’d only need to get rid of a few. . . .

I grab the knife and reverse it, using the hilt to hammer at the pegs from the inside, so they push through the hole in the frame. It takes me a few minutes to get the angle right, balanced on my tiptoes on the soft mattress, but after a moment’s effort, the first peg pops out, taking several lengths of red thread with it. It doesn’t travel very far—the thread is wound and crisscrossed so complexly that it snags on the pattern. But it’s a start. I move to the next peg and hammer it out. Then the next, and the next. With each peg, the hole in the cat’s cradle gets larger. After a few minutes work, there’s a gap in the design that’s wide enough for me to sidle out, and I drop to the carpet with a thud.

I had plans for this morning. To see the moor for the first time. To gaze out at Agathion’s grounds in the early morning light and ready myself for the day. To don my uniform, one piece at a time. It was supposed to be a ritual. A new beginning.

Instead I’m dashing down the corridor in my pajamas to the bathroom, yanking a brush through my hair as I do so. The corridors are empty and silent.

The bathroom is wet and freezing cold. Globs of toothpaste congeal in porcelain sinks, and everything smells artificial and feminine—hairspray and cosmetics, which I didn’t think we were allowed to have. I pee, then turn the hot faucet on, but only ice-cold water emerges. I splash my face, then sprint back to my room.

My jeans and puffer jacket from the night before are gone, along with my underwear. Will I ever get them back?

I yank on my uniform without reverence or ritual. White underwear. White bra. Ivory cotton shirt. Brown stockings. Tartan wool skirt. Knitted sweater. I’ve been practicing how to tie a tie at home, using the one my father wears to weddings and funerals. His limp polyester thing is from a different universe than this buttery-soft silk, and my awkward cold fingers fumble. My attempt is embarrassingly bad, but I don’t have time to try again.

My school shoes are the right size, but the brown leather is stiff and unyielding. I’ll have blisters by the end of the day.

I pull on the brown tweed blazer. The herringbone pattern is subtle yet intricate, the wool soft but firm under my fingers. There are suede patches over the elbows and brass buttons at the cuffs. I run my fingers over the sword and cup of Agathion’s crest embroidered on the front pocket, and I feel my heart grow steady.

* * *

The worn-carpeted corridors of Agathion are empty as I make my way down the creaking wooden stairs. I glance out the window into the courtyard, but everything is heavy fog. I can just make out a looming shape, a dark, monolithic thing, half swallowed by gray emptiness. But I don’t have time to wonder about it. I follow the sounds of adolescent chatter and the scraping of cutlery on crockery until I find the dining hall.

I pause outside the door for a moment, not sure what to expect.

The bitter, sharp taste is still at the back of my throat.

Heads turn as I enter, and I feel the burning heat of attention. My collar is too tight, my wool stockings too itchy. My hands are hot and big, too big, like shiny pink balloons attached to my arms. The dining hall is crowded with tweed and bright eyes. It’s a large room—big enough to accommodate all eighty-ish Agathion students, sitting at tables of six or seven. A huge fireplace is against one wall—large enough to roast a whole pig on a spit by the looks of it. Above the fireplace, mounted on a wall, is a huge, ancient-looking sword, with a flat blade and a simple iron ring attached to the pommel. The full-sized version of the knife on my pillow. I touch my blazer and the sword embroidered there.

Four black-robed adults sit beneath a huge stained glass window depicting the seven labors of Hercules. I recognize Magistra Hewitt at once, her eyes turning sharply to me. Beside her is a sallow-faced old man in wire-rimmed spectacles. I’m guessing he’s the headmaster, Archon Leek. Next to him is a somewhat younger woman with a thick bun of dark hair, who is murmuring to a large, bald-headed man.

The old man—Archon Leek—stands slowly, his chair scraping as he pushes it back. His eyes don’t leave mine, his gaze assessing.

There’s a moment of silence that lasts for an eternity. Empires rise and fall in that moment, and all I want to do is disappear.

Then the Archon brings his hands together in a slow but firm clap, the sound sharp in the silent room. He brings his hands apart and together again. And again.

Then there’s a noise like thunder, a rolling, pounding that I realize is people’s feet stamping on the floor.

The room breaks into applause. A few people whoop and cheer.

I am so confused.

“Welcome, Piglet!” says Cyrus, coming forward to pat me on the back.

A girl with braces and tight braids hands me an empty plate, and Cyrus ushers me over to several tables at the side of the room, which are groaning with mountains of food.

“The red thread is an Agathion tradition,” he explains with a smile. “The first step toward freedom is to truly see the things that bind you. The web. The net. The cage. It’s only then that you can break free. Something like that, anyway.”

I glance back to the high table, and see all four magisters watching me. I think I did the right thing, so why do I feel like a mouse being watched by a parliament of owls?

I shake the feeling off and consider my breakfast options.

I’m not sure what I was expecting, in terms of the food at Agathion. Maybe some organic brainfood kale-smoothie business. Or limp bain-marie misery. What I didn’t expect was an Enid Blyton level of boarding school food-porn.

I see platters of sausages that aren’t soggy or greasy—they’re bursting with fat and look like they’ve just come off a sizzling griddle. The scrambled eggs are creamy yellow and look light and pillowy as goose down.

There are mountains of crumpets. Great slabs of butter. Tureens full of baked beans—clearly not the lurid orange kind you get in a can. These beans have been lovingly spiced and stewed. I see grilled tomatoes and mushrooms, and slices of something dark and rich-looking. A vat of porridge. Jugs of creamy milk and freshly squeezed orange juice.

It’s a bit overwhelming, to be honest. I take a crumpet, some butter and jam, and an apple from a spilling cornucopia of fresh fruit.

“Did you use the knife?” Cyrus asks me.

“Of course she did.”

These words come from the most beautiful girl I’ve ever seen, who has sailed up to Cyrus. She has golden brown skin and a mass of dark hair that is so shiny and bouncy, it’s like a living thing. Her gaze slides over me as she registers that I’m of no interest to her. She makes me want to vanish, to sink into the ground like the Wicked Witch of the West, to dissolve until I’m nothing but a smudge.

Cyrus waits for my answer. I nod.

His expression falters a little, like he’s disappointed. The girl makes a satisfied little noise.

“I didn’t cut the thread, though,” I say.

A grin spreads across Cyrus’s face. The girl shrugs and drifts back to a table of girls who are beautiful, but not quite as beautiful as she is.

There’s this thing with trees in a forest called crown shyness: if you look at the canopy, there’s a little gap between the outline of one tree and the ones next to it, so they never quite touch each other. This girl is like that. The others aren’t avoiding her—just giving her space. And she occupies that space with such a haughty sense of entitlement. I can tell she’s the queen of them. Possibly of the whole school.

“Good work, Piglet,” Cyrus says.

Then he’s drifting away, too, off to his own table. I feel a sting of disappointment, and realize I’d been hoping Cyrus would invite me to sit with him. There’s an empty seat available and everything.

Perhaps the invitation was implied?

No.

No friends.

Not after what happened to Cassidy.

A scruffy boy with an untucked shirt and dark hair falling into his eyes slides into the spare seat that could have been mine. He says something that causes the other people at the table—a magnificently tall, broad-shouldered girl with a shaved asymmetrical haircut and a much shorter, slight boy with neat pale curls and silver-rimmed glasses—to burst out laughing.

I swerve away from their table and nearly collide with a skinny boy staggering under the weight of the biggest breakfast I’ve ever seen.

“Careful!” he says, and I scurry to an empty seat. Each table is stocked with a large pot of what I assume is tea, with a cup and saucer at each place. I notice a staff member in a starched gray uniform moving around replacing the pots with fresh ones.

There are three other people at my table. One is down near the end with his nose buried in a book (Virgil’s Eclogues), and two are deep in conversation about some kind of recent sporting match that I’m not nearly interested enough to learn about. Without pausing their conversation or looking at me, one of the sporty girls leans over and pours tea into the cup in front of me.

“Thank you,” I say.

She nods distractedly and keeps talking.

There is milk, sugar, and lemon on a tray in the center of the table, but I’m hardly a tea expert, so I leave mine plain. As I look around, I see that whenever anyone sits at an occupied table, they get a cup of tea poured for them. Another Agathion tradition, I guess.

I lift my teacup from its saucer. It is fine bone china, delicately painted with fat purple-black mulberries and feathery green ferns. The rim is lined with gold. I’m almost scared to hold it in case it breaks. I take a moment to breathe in the fragrant steam, and then take a sip of the amber liquid. The tea is bitter and bold, with hints of honey and spice. The warmth of it spreads through me and brings a sense of serenity.

The crumpet is also amazing. Buttery soft, with the jam exquisitely balanced between sweet and tart. I wish I’d taken five. The rich tannins of the tea cut through the sweetness of the crumpet, and it’s all so perfect, so why don’t I feel satisfied?

My gaze drifts back to Cyrus and his friends.

I’ve never fit in at school before. Or anywhere, really. I had one friend at St. Catherine’s, and look at what happened to her.

I know that I didn’t come here to make friends. I came here to learn self-control. To live a life of the mind, like the brochure promised me. To not be ruled by feelings, to be led only by logic and rationality.

But . . . would friends be so bad? Especially if they were intellectual friends. People who could challenge me. Keep me in that rational realm.

I want to be over there, I realize. I want to be part of that conversation. I want the social ease that they have with each other. The familiarity. There is so much that I want, that sometimes I feel like I’m nothing but want, held tenuously together with skin and bone.

My whole life, I’ve felt like I’m longing for something, without knowing what it is. I thought maybe coming here would help. Maybe in this beautiful place, surrounded by books and ideas . . . maybe I could rise above my feelings, my wanting. Exist on a higher plane.

But maybe the problem wasn’t my old schools. Or my family. Or the other kids who always looked at me like I was something completely alien to them.

Maybe the problem is, and has always been, me.

I don’t hear a bell ring or anything, but students start to get up and drift toward the door. I notice the girl from before—the queen—pause by Cyrus, laying a hand affectionately on his arm. There’s such ease in that gesture, I know she does it every day. He leans forward and brushes his lips against her cheek, and her lips curve in a smile.

Of course they’re dating. The king and queen of Agathion.

Cyrus’s eye catches mine, and I feel heat spread through my cheeks as I’m caught staring. The queen follows his gaze to me, and the faintest wrinkle appears in her perfect forehead.

“Are you the Piglet?” A horse-faced boy stands in front of me, holding a crumpled sheet of paper.

I nod.

“Here’s your timetable and weekly reading list.”

He shoves the sheet of paper at me. A timetable on a grid and a list of books, covered in amber-colored stains.

“I spilled tea on it,” he says by way of explanation.

The timetable seems . . . unfinished. Only one actual class per day, plus a weekly lecture and a meeting with Magistra Hewitt.

The reading list, however, is extensive, and largely unfamiliar to me.

Marcus Aurelius. Thucydides. Plutarch’s Lives. Plato’s Republic and Parmenides.

I wasn’t expecting to see any Maya Angelou or Toni Morrison, but no Dickens? No Austen? No Dumas? No Shakespeare?

This must just be my history reading list. There’ll be a different one for literature, I’m sure of it.

Am I supposed to read all of this in a week? I feel a little throb of anxiety—what if I’m not smart enough to be here?

I look up, but the horse-faced boy is gone.

My one class isn’t until after lunch, so I guess it’s time to get reading.

* * *

The library is everything I’ve ever dreamed of.

Cluttered but grand, with dark wooden bookcases that fill every inch of wall space. On every surface there are books bound in leather and cloth, with gilt lettering stamped on the spines. There are wooden ladders on wheels to reach the higher shelves, and narrow spiraling staircases in black wrought iron travel to balconies crammed with more books.

The thing about books is that they’re complete. When you read a book, you know the whole story will be contained within its pages. All the information the author wanted to convey is there. Not like human minds or memories, which are weak and unreliable. Books don’t change. They don’t forget. They don’t start screaming whenever they see you.

Books are better than people.

Books are safe.

A silver-haired woman perches on a stool behind a large mahogany desk. She glances up as I enter and nods briefly in greeting, then goes back to her work, which appears to be repairing the binding on a particularly old tome. She isn’t wearing academic dress, so she’s not a magister. She must be a member of the day staff. She looks like someone ordered a stern librarian from a brochure—pointy gray face, tight gray bun, and neat, unflattering gray skirt and jacket.

A huge card catalog crouches by the entryway beside a towering grandfather clock, and at one end of the room I see several wooden desks with leather inlay, lit with green banker’s lamps. Students sit at these desks poring over old books. Some wear white gloves and turn ancient pages with extreme care. Others have piles of different texts spread out before them, scribbling notes with pencil stubs.

A tall, narrow window lets in thin light from outside. Beyond the window, all I see is gray.

I stand there for a moment and take it in, inhaling leather and the earthy, almost biscuity smell of slowly decaying paper—the gloriously comforting, soothing scent of old books.

Eyes turn toward me, staring. I feel naked, like these people already know that I come from an ordinary school and an ordinary family, from an ordinary suburb of Florida. I’m not rich or famous or important. I’m an impostor at this posh school with its tweed blazers and ties and fancy breakfasts and haughty ivy-clad towers.

I wonder—not for the first time—if I’ve been kidding myself all along. The one nagging doubt I’ve had about coming here has never been that Agathion wouldn’t hold up to my own fantasies. It’s that I wouldn’t. What if I was a clever, weird fish in my ordinary pond, but now I’m nothing more than a below-average minnow? A maladjusted tadpole? What if my intelligence—the one thing that I’ve built my identity and my self-worth around—whatif it’s not enough? What if everyone here is smarter than me, and they all know it?

What if I’m ordinary?

The librarian looks up at me, like she can hear my thoughts.

“Can I help you with something?” Her tone suggests that she doubts it.

My cheeks burn, and the library suddenly feels too hot and close. The collar of my blazer itches against my neck.

“Literature?” I manage.

The librarian raises an eyebrow, but points to rows of tall wooden shelves at the back of the great room.

I scurry to where she indicates, away from prying eyes and curious whispers.

Dark leather spines welcome me, and I run a soft hand over them, feeling my heart slow. This is where I belong. Here, with the books.

I seem to be in the wrong section, though. I can see Ovid and Virgil, and a slim volume of poems by Sappho. Where is the English literature? Or . . . anything written after the fall of Rome, for that matter? I move deeper into the narrow space and go around a corner until I’m surrounded on all sides by high wooden shelves that clearly haven’t been dusted for a while.

Cicero. Livy.

Hesiod. Herodotus.

I know that Agathion loves its classical scholars, but surely there must be some English literature here?

Right?

I’m so focused on the books that I don’t notice I’m not alone, until I tread on someone’s foot. The owner lets out an outraged yowl, and I spin to face them.

It’s the scruffy boy from before. The one who sat next to Cyrus. He has pale skin, fine cheekbones, and lips that look almost bee-stung. The top two buttons of his untucked shirt are undone, his tie askew in a way that doesn’t look deliberate. His shoes are scuffed and his laces untied. A sprig of lavender is attached to his blazer lapel with a safety pin. He looks like he slept in his clothes, and there is very clearly a large book stuffed up his sweater.

“Sorry,” I say.

He stares at me, like I’m some kind of banshee that’s been summoned to ruin his day.

“Who are you?” he asks in a thick Scottish accent. “I haven’t seen you before.”

“I’m new,” I say. “I—I think I met your friend last night. Cyrus?”

The boy narrows his eyes. “Handsome? Charming? Probably getting himself into nine kinds of trouble?”

I remember the pig and Cyrus’s cheeky grin. “That’s him.”

“He’s nice to everyone,” the boy says dismissively. “You shouldn’t take it personally.”

I don’t know if the boy means this statement to be hurtful, but I am already having quite a day. Mortified, I feel blotches spread across my cheeks and tears start in my eyes.

No. No feelings.

I try to breathe, to get control over my body that is spiraling into physical panic.

“Hey,” says the boy, frowning. “I didn’t mean—are you okay?”

“There isn’t any literature,” I manage to get out. My hands feel hot, my chest tight.

Footsteps sound nearby, and the librarian appears.

“Oak Redferne,” she says in clipped tones of disapproval. “Is there something up your jumper?”

Oak clears his throat and grabs my elbow. “Sorry, Ms. Winston,” he says. “But Piglet here is looking a wee bit peely wally. . . .”

“My name is Page,” I croak.

“If you say so,” the boy replies, steering me past bookcases and study desks.

“Come back here at once, Mr. Redferne,” the librarian says.

“Can’t!” The boy—Oak—calls over his shoulder. “She really needs some fresh air.”

The librarian makes a frustrated noise, but doesn’t attempt to follow us. I half expect Oak to abandon me in the corridor outside the library, but to his credit he guides me down a flight of stairs and out a large wooden door into the central courtyard.

Agathion is still wreathed in fog like a castle floating in the clouds. I’m desperate to see the landscape beyond the school—majestic mountains and bleak, romantic moors. But currently there’s nothing but mist.

Oak strides long-legged into the white emptiness as if it’s an old friend, stretching out his arms and brushing his hands through the mist, which swirls and dances around his fingertips.

He looks like a creature from another world. A fairy prince or perhaps a trickster crow in human form.

“Are you coming?” he says over his shoulder.

I guess I am. I scurry after him, the cold air seeping into my bones. I’ve never been this cold . . . but I’ve also never felt this alive. The muggy heat of Lakeland, Florida, left me in a kind of perpetual daze. My mind feels sharper here, my senses heightened. I can smell the fresh scent of frost, the tang of manure from the farm. The damp musk of ancient stone.

“Who’s your tutor?” Oak calls back to me.

“Um,” I reply. “Ms.—Magistra Hewitt.”

“And did Hewitt tell you what you should be doing today?”

“I have a class this afternoon. And someone gave me a reading list.”

“Do you have a tour guide?”

“I think I’ll just head back to the library and get a start on this.” I wave the list.

Oak sighs, a deep, world-weary exhalation. “It’s your first day,” he says. “Someone should show you around. And I guess for lack of any other volunteers, I’m the someone.”

I half expect him to turn and head back inside, but instead he strides away into the mist, toward the center of the courtyard.

Am I supposed to follow?

“Come along, Piglet,” says the boy.

“That’s not my name,” I manage to say as I scurry to catch up.

He shrugs. “Every new student is Piglet,” he says over his shoulder again. “Agathion tradition.”

“How long does it last?”

“Until a newer piglet arrives.”

Great.

“This is the forum,” Oak says, spreading his arms and twirling in the mist. “The social hub of Agathion.”

Something huge and dark looms out over me.

A stone.

A massive stone, standing on its end, reaching almost to the second floor of the surrounding building, and at least six feet wide.

“What’s that?” I ask.

Oak’s jaunty expression dims. “Standing stone,” he says, his voice somewhat solemn. “One of six. This hill is a sacred place. Or it was, until someone built a school on top of it.”

I peer through the mist, trying to make out the other stones, but find none.

“They look very old,” I say.

Oak nods. “Four and a half thousand years, give or take. They have names, too. This one is Sgeul-Rùin, which means secret in Gaelic.”

Four thousand years. It feels impossible that something so ancient and special is just . . . plunked in the middle of a school courtyard. Shouldn’t it be behind a rope? Protected somehow?

“What are the other ones called?” I ask.

“Ùir,” Oak says, pointing through the mist. “Earth. Anail, which means breath. Fuil is blood. Tiodhlac is a gift or a present. And Cuimhne. Memory.”

I reach out and touch the rough stone of Sgeul-Rùin, and Oak seems to flinch as my fingers make contact.

It’s bitingly cold. Something whispers in my ear, and I drop my hand, wiping damp fingers on my skirt.

Oak’s eyes are slightly narrowed. “Come on,” he says and strides off.

I follow, trying to shake off the feeling that the stones are watching me.

We cross the courtyard, passing an elegant open rotunda, with a domed roof supported by white columns.

“The monopteron,” Oak informs me. “Sometimes people hold debating matches or poetry readings and use it as a kind of stage. But mostly it’s just somewhere to sit and eat lunch.”