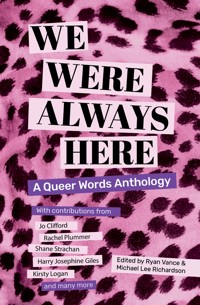

We Were Always Here E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: 404 Ink

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

From drag queens and discos, to black holes and monsters, these stories and poems wrestle with love and loneliness and the fight to be seen. By turns serious and fantastical, hilarious and confrontational, We Were Always Here addresses the fears, mysteries, wonders and variety of experience that binds our community together. We Were Always Here is a snapshot of current Scottish LGBTI+ writing and a showcase of queer talent.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 256

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

We Were Always Here

Edited by Ryan Vance &

Michael Lee Richardson

Content Warnings Index

Assault

Queer the screen II

Are You Lonesome Tonight?

Abolish the Police

Stranger Blood is Sweeter

daughters of god

Deadnaming

Adjustment Period

Death

Jellyfish

Abolish the Police

Smudged

Titan Arum

Homophobia

Jellyfish

301.4157

Borrowed Trouble

Not This Again

Racism

Ancestry

daughters of god

Sexual Abuse

daughters of god

Suicide

Jellyfish

Surgery

Free Nipple Graft Technique

Foreword: Bending Time

Garry Mac

Positioning queerness in time is a creative act.

Often, queer people are where we are not spoken of. History is replete with erasure: closets, lacunas and gaps. We have no exodus or diaspora, nothing to tie together our collective reality. We are always new; each generation must necessarily create itself out of whole cloth. At least, so it was until the first brick was thrown at Stonewall by Marsha P. Johnson. Or Stormé DeLarverie. Or Sylvia Rivera.

Or was it before then, when authors like Woolf and Wilde performed queer narratives sub rosa, escaping the ever-present policeman’s gaze of heteronormativity?

Perhaps our emergence from latency began even further back than that? Looking back into the past, we can find ourselves in those ephemeral traces, not a linear narrative but a fractured, fragmented existence, struggling to make itself known.

But when it comes to queer history, reliability and authenticity are less important than the narrative into which we write ourselves. When the individual takes up the task of rewriting state historicity, we find power in our pen. Whether we’re actively oppressed by the State, society or the internal policeman installed in our heads, queerness has historically been an existence that pushes at the boundaries of what is allowed. With gatekeepers on every side, simply existing in space can be an act of resistance; making decisions for ourselves becomes a revolutionary activity. Interrogating sex, gender and romantic attraction changes you on a subatomic level; remakes you from the ground up.

Peeking behind the curtain of dominant cultural narratives reveals a wrinkled, grey and naked conjuror, shitting on a golden throne, wanking into his own shadow, tricking us into believing he has power.

Once the magical techniques are revealed, it’s impossible to fall for the illusion, to return to a binary life. Yet, it is equally impossible to escape the fact that we live within those dominant narratives. Theory alone is not a powerful enough magic with which to bring those structures down.

There is, however, a spell written into the fabric of the curtain:

‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.’

This spell is designed to keep us locked into the circularity of the present, and such reliance on an imagined past is at the root of many violent ideologies, bolsters ideas of supremacy, and stunts our growth. Unless we can imagine a better future, we are doomed to history.

If that thought feels too heavy, take heart; intrinsically linked to the queer mode of being beyond time is the notion of queer futurity.

To paraphrase Jack Halberstam, our entire relationship with time is strange, imaginative and eccentric. Queer time is not the same as linear, reproductive time. Without the milestones of birth, adolescence, marriage, child rearing, work, retirement, death, each of our lives become fragmented on the individual level, a microcosm of our fractured collective history.

Such fragmentation need not be a chronic source of trauma, with its attendant nihilism. Instead, it offers us the possibility of reframing ourselves in the present, standing on a horizon of becoming, looking towards a future that is not fractured, but full of fractal potential.

Freed from the constraints of linear time, we instead find ourselves unbound, existing in potentia. Unbound from time, we are free to make ourselves into whatever we wish. Will becomes the sole drive, the will-to-become.

Without societal expectations and conditions, queerness is a technology of the future; we are that which is not here yet. Utopia may seem like an unrealistic pipe dream if one belongs to linear time; but it can also serve as a direction that is otherwise difficult to describe. It is the act of facing the future. Allowing ourselves to become what we see is the supreme performance of futurition.

To face that future, we need to investigate our presence in the ephemeral past, and make space for ourselves in the present.

Our existence today is privileged because, perhaps for the first time in recorded civilisation, our lives are indelibly stamped on culture. Complexifying media and the rise of the internet has allowed us to form countless, interconnected rhizomes of recognition. Those of us who work in cultural production are telling stories, openly and without fear of censure. Those narratives are increasing in quantity and scope, and they have worked their way into the fabric of the dominant narrative so well they are now difficult to unpick. In other words, we have reached a tipping point.

It may in fact be impossible to erase us from historicity-in-the-making.

It is not in homogeneity, but in this diversity (that much-maligned word) that evolution thrives. What we do with that visibility, and the power we derive from it, may depend in part on which direction we are facing. If we turn ourselves from the past to face the future, what utopias might we begin to imagine?

* * *

José Esteban Muñoz argued in Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity that queer futurity ‘illuminates a landscape of possibility for minoritarian subjects through the aesthetic-strategies for surviving and imagining utopian modes of being in the world.’ Such transgressive and creative acts of imagination can be found most in cultural production, not merely in academic theory.

The anthology you’re about to lovingly break the back of is one such timely piece of cultural production, pushing at its seams with eccentric notions of time and the pure ontological joy of owning our space and being here. It is thrilling to read a collection of diverse queer voices and themes, not drawn together to talk about queerness, but to talk queerly. To tell queer stories in the here and now, that stamp their perspectives ineradicably on the dominant narrative of the present.

Inside, you’ll find filmmakers struggle to piece together the celluloid history of such a diverse group of people, leaving gaps in the reel to stand in for those voices erased by censorship and historicity. Fragmented poetry reads more like fractal holography, shimmering in gel-coloured lights, while victimised ‘faggots’ invert the void within them and elongate, blossoming into something bigger than anyone could imagine.

Boundary dissolution thrives within, too; queer love is often a complex series of interpersonal transactions that weave between wanting to be with someone, wanting to be someone, or wanting them to absorb you, wholesale, and fix the broken parts of you. Or of transcending material love entirely, merging into pure consciousness and experiencing union. And, so, we have stories of relationships that flit between platonic connection and desire, love that thrives in its forbidden nature, love as worship; of the self, of others, of queerness itself.

There are dark and dangerous narratives here, too: excavations in the footnotes of queer history, private grief and shame shared publicly (reparation-in-progress) and reports from the frontlines where queerness violently intersects with normativity.

Poetry transcends slogans, ripping them apart and making them into a creative act of resistance.

And, here and there, hints of glimmers of that fractal queer futurity, that not-yet-here sense of surfing the peripheria of time.

More than anything, though, this anthology is the sum of all its parts; there’s a rhythm here that allows each discrete unit to become part of an undulating whole.

You’ll read it, and not question the identity of the authors, nor feel the need to establish their queer credentials, because the queerness within is not just in the narratives, but in the experience of reading. The shared connection between you as reader and the many writers contained within is a glittering empathetic echo of the collectivity that is required for any hope of a queer future.

Swim in it; let it fill you with light.

Put down the book, once complete, and walk away energised, queer creative juices flowing, eager to contribute your refrain to the greater song of queer experience, through the power in your pen. A song that, in this book, is thrilling, enthralling, compelling, uplifting, bittersweet, chaotic, beautiful and diverse; complex enough to be profoundly queer, and never worrying about being representative.

Read it and recognise that we were always here, and you are here, now, and so are they, and we are all in this, here, together.

Heather Valentine

Projector

The film flies through Angie’s cotton-gloved hands, disappearing into the reel. Cut three. She turns the canister, positions it to feed into the projector. Molly sits in the computer chair, white fingers twisted through long brown hair, round glasses illuminated bluish-white by the first flash of pre-film.

Black and white pictures move across the makeshift screen, a bright square on bare wall. Angie moves to sit on the desk with her back to it.

She’s getting sick of seeing them.

The room is quiet apart from the click of the projector, making her own silence awkward. She glances at the back of Molly’s head, catching the film in the process. Two classically beautiful women run on the beach, laughing, one of them holding a length of light fabric above her head that blows in the wind. Angie looks away until the room turns dark, and clicks the projector off.

‘It’s… nice,’ Molly offers as she turns the lights back on.

‘Nice?’ Angie replies.

Molly turns her head. ‘It’s not a very Angie film, is it?’

Angie slumps, still sitting against the desk. ‘The brief said celebrates. Use material from the from the Pink Pictures archive to create a short film that celebrates LGBT film history.’

‘So you made some twee bollocks,’ Molly says.

‘So I made some twee bollocks,’ Angie sighs.

Molly turns around to face her, leaning her bony arms on the back of the chair. ‘It needs to be a bit more punk, yeah?’

Angie nods, then shakes her head. ‘But it’s this uplifting shit that goes viral.’ And she lifts her hands to gesture around the room. ‘I’m not going to be able to use this after I graduate. I can’t rent this shit myself. I need to start making things people want to watch. Autostraddle left Monster out of its Top 100 Lesbian Films because it was too depressing. I can’t just be my depressing self. It’s not what people want.’

Molly shrugs. ‘I mean, I guess it’s a response to the mainstream media, dead lesbians etcetera. Radical positivity.’

‘Is twee bollocks still radical?’ Angie asks, raising an eyebrow. ‘I mean, which is it?

‘You know it’s complicated,’ Molly replies. ‘But I was devil’s advocating there, sorry. Not helpful.’

Reels and reels of Angie’s rejects sit in her locker. Collages of Italian horror movies, lurid blood-stained murderesses, loving tributes to bisexual psychopaths and lesbian predators, re-cutting scenes of knife-crazy trans women to remove double-takes in horror or amusement and leave them as powerful, nasty and vulnerable as the dark-haired male villains that big-hearted teenage girls grab on to. No nice people. Real messy mental queers like her, real out of control screaming like she is when she has an episode.

Thank you for your submission, but it’s not quite what we’re looking for.

‘Besides, you know what else I’m going to say,’ Molly says.

And Angie does. ‘It’s all bourgeoisie white cis lesbians, and I shouldn’t sell that to people as queer history even if that’s what they want.’

Molly smiles awkwardly. Yeah, it was that. ‘There were a couple bourgeoisie white cis men for variety,’ she adds.

‘I’ll see what I can do before the deadline to fix some of that,’ Angie says. But if she can’t, this is how it’s going in. ‘Anyway.’

Molly reaches for her bag. Angie reaches for the keys to lock up.

‘I’ll walk you home, yeah?’ Angie says. Molly smiles, drawing up to her full height. Angie flicks the last light off as they leave, and shuts the door on the studio.

Angie can’t sleep again. She finds herself up at four in the morning, hunched over her laptop on her bed and flicking through the Pink Pictures archive again.

They said LGBT film history, and they meant history alright. A lot of the films in the archive are Hays Code, pre-Stonewall, however you like to put it. All subtext. She can look at a film and feel that someone is bisexual like her, but how can she make an audience who isn’t looking see that reality?

Marlene Dietrich? Molly’s voice says in her head. Marlene Dietrich’s films are still in copyright and the archive is all UK films, so she isn’t there and she can’t add her in. There isn’t a lot she can do about the whiteness with what she has, either — the early African-American film pioneers she knows from class are, well, American.

Either way, she makes gaps for them. In the cut four file, deleting some of the tamer glamour shots. Pulling apart seconds to put herself in.

Some of the subtext films have hetero pairings in them, she could cut around them with actresses that look similar. The short, amateur, real collection gems don’t, so there isn’t a lot to work with there. A few people in androgynous style, a handful of drag queens, and the films are from a time when that could have meant they were trans. Or it could not.

Her hands fly across the keys, pinching clips. Then they stop. A collage can bring out subtext and make it text. Or it can make text appear that isn’t there. Is she doing bisexuals like her or trans women like Molly a disservice if she tricks them into thinking the films in this archive have something in it they don’t?

It’s why she shied away from touching the edgier films, and dove more into the identity politics heartwarming angle. Because there were about three experimental films that still hold up and at that point she might as well have just copied them and sent them in as her entry.

What she’s looking for isn’t here. What’s here is two handsome men, two pretty women, being gently queer. And she’s sure there are ways in which that is still radical, but not with her. That’s the starting line to her. Watching nice films over and over again isn’t her. Watching films just for their representation isn’t good enough. She wants to feel the ground break beneath her feet.

Celebrate isn’t the problem. It’s that what she wants to celebrate is invisible.

There has to be a queer female Derek Jarman, Jean Cocteau, Kenneth Anger, Oscar Micheaux. A queer female Stanley Kubrick, Dario Argento, Bill Gunn, Quentin Tarantino, even.

She has to be out there, waiting to be celebrated, and Angie just hasn’t found her yet.

Angie starts up the file-to-reel she borrowed from the studio. She prints her new cut, same length, black holes where her history should be. She already feels guilty, like she always does when she goes too far. It’s a waste of film, she’s never going to send this cut in. She’ll screen it for Molly, yell a bit and then send in the twee bollocks because the deadline is next week and she has classwork to do too.

Maybe this isn’t a very Angie project, then, she imagines Molly saying. But she can’t expect to only do things that are perfect for her if she wants to be a professional. She doesn’t stop the reel.

Maybe she should have stitched together the lying cut. She works on it while she waits for Molly to arrive. Keeping herself busy. The film is already in the last projector that was free, chairs pulled up. Maybe she can cut together speeches to the camera, insert a sexual ambiguity through the meta-knowledge that the audience could be of any gender or identity.

The door opens and Molly comes in, hands fussing with her satchel strap.

‘Molly, I’m going off track again,’ Angie says.

‘Alright,’ Molly replies.

‘Is it still a celebration of LGBT history if I’m basically making a new film?’

‘Not really, no,’ Molly says, hanging her brown faux-suede coat on the back of the door. ‘Maybe keep that for another submission.’

‘Right, thanks.’

Molly crosses the room towards the seat closest to Angie. ‘Is this on track?’ she asks, gesturing at the projector.

Angie shakes her head, then shrugs. ‘I don’t know. It might be. I don’t think so. I wanted to show you anyway.’ She catches Molly’s eyes as she props her glasses up. ‘I think it’s good. I need to make sure it makes sense outside of my head.’

‘Okay, I’ll try and figure it out,’ Molly replies.

Angie clicks the light off, and the projector on. The same twee bollocks opening scene, a classic beautiful shop assistant looking longingly at a classic beautiful rich woman leaving the store. The first blank. She looks away again. If Molly doesn’t like it, she doesn’t want to see it on her face.

The projector rattles, and to Angie’s ears makes a worrying noise. She turns around to see it approaching another gap. The projector goes dark. Flicker flicker, filaments of light dance in her darkness, shapes like figures.

‘Oh, fuck,’ Angie mutters. The filmstock must be damaged. She must have grabbed a faulty canister, maybe touched it somehow.

‘What?’ Molly says, turning to look during the next twee bollocks sequence.

‘They’re supposed to be blanks,’ Angie says.

Molly opens her mouth to answer, then turns back to the projector at another stretch of darkness. The streaks of light come back, and like clouds she imagines she can see them in more detail, make out hands and mouths.

‘No, this is better,’ Angie says, as the beach women sequence plays again. ‘They’re like — the ghosts of films that should have been.’

The last normal sequence plays out, and the projector flickers into a few last seconds of darkness, the lights seeming to get brighter. Then the projector stops.

‘It’s like what you say about your horror films, and your collages. It’s taking subtext and making it into something real.’ Angie smiles as Molly continues. ‘Like, uh, Lovecraft and depression.’

‘Hey, keep that racist clown out of my studio,’ Angie laughs.

‘Like Poe and — oh wait, slavery apologist,’ Molly replies.

‘Like the Vincent Price film versions of Lovecraft and Poe’s books,’ Angie suggests.

‘Yes, he’s an angel,’ Molly grins, before her eyes fall back upon the projector. ‘But anyway — yes. You’ll need to foreground it for someone who doesn’t know what your angle is. Celebrating queer history from the archive, and mourning queer history that was lost. It might not be right for this sub if you’re sure it’s a twee bollocks sub. But it’s good.’

‘It’s good to hear you say that,’ Angie says. ‘And I like your subtitle, I’m stealing that.’ She can take this to class, ask her professor for advice on turning it into something original. She begins to dismantle the projector set-up, moves to pack up the film reel.

‘You’re welcome to it,’ Molly says. ‘Anyway, it’s your turn now. Let me just boot up my laptop and I’ll show you my new draft.’

Angie smiles vacantly at the space on the wall where her film was, as Molly rustles in her bag. When she blinks it’s almost painful. As if they’re still shining there, the dancing shapes emerge against her eyelids, burning green and blue.

* * *

The twee bollocks reel lies on Angie’s desk, packaged up and labelled for Pink Pictures. She sits on her bed, eyes towards the ceiling, where blue speckles still glitter in her vision. Aching, throbbing. She is putting this down to some sort of dehydration, eyes strained from computer light and the dryness of the projector rooms.

She turns back to her laptop anyway, hands moving without thought, following her instincts as the shapes seem to float behind this file or that. Looking for pieces of her original vision, still half-wondering if she can pull out a better version of her submission in time, splice in Molly’s subtitle and send the ghost version in.

The sound of someone else coming into the dorm. Angie glances away, and when she turns back she’s lost. She can’t make sense of what she’s chosen. She looks through her notes, as if waking up from a dream and trying to remember it. Seeing the phrase heighten the melodrama and not being sure what she meant or how she meant to go about doing that when she wrote it down.

Angie puts the laptop on the floor and lies back. That turn her brain can put on her, the head-tiredness, the nausea and the anger, flows at the edges of her mind. She’s at the point where she can still notice them. When she crosses the line, she won’t even realise. Rubs her eyes with her palms, and the pain splits her skull, a line across the top of her head from the base of her neck to between her eyebrows. Her whole vision filling with a multi-coloured burn, a shape like a face emerging in the middle, still the colour of her eyelids. She isn’t scared. She’s annoyed. Tries to hold on to Molly’s praise, pull herself back, but it slips. Just restlessness, and itchy hands.

Too early, not enough sleep, Angie comes back into the studio, rucksack full of reels, the disintegrating film hot against her shoulders. Finds a room, sets up a projector. Lets it play. The shapes grow larger, brighter. The tears don’t just stay in the darkness now, they cut across the archive tapes. Blotting out the actresses, seeming to create other figures.

The film flies through Angie’s cotton-gloved hands, as she sets it back to the start.

Her first clips have almost completely gone now. Only the classic beautiful shop assistant remains, shakily moving through the light. She also wrote social-realist screenplays, but they were never produced. In the blanks, daguerreotype sketches of unknown films, strange women in occult costumes in one reel, throbbing neon modernism in the next. Screened at local film festivals, but never picked up. The light crawls, the walls cracking and splitting, the way it feels like her head is. She can barely feel anything other than the pain now, is vaguely aware that her fingertips are moving to touch the projector controls, until all her peripheral vision is filled with the multi-coloured light.

A cooling sensation like water, fingers brushing her eyes shut.

‘Why do you think it hurts, Angie?’ A soft, husky voice.

‘I don’t know,’ Angie replies.

‘The same way it hurts when you have been sleeping, and someone turns on the light.’

The pressure releases from her head. Angie opens her eyes. She sees, in flickering technicolour, a woman standing in front of her. Through an archway behind her, a scene of theme park Grecian paradise, blurry like the last surviving set photo of something lost. Plaster props, all sorts of people behind her dressed in costume.

‘It’s like the ghost,’ Angie murmurs. ‘Of the films that should have been.’

‘There’s no should have,’ the woman replies. ‘Only have. You are not building a first. You are building on the rich tapestry of the hidden world. This is reality, Angie.’

Her film flickers through her eyes, imprinted in double over the paradise set. Some of the women, some of the drag queens, some of the androgynous dressers lit up in a blue-green halo. Her reject reels, the horror films and the strange experiments she’s watched, woven with their own filaments. The daguerreotypes, flashes of strange visions. The fault line she’s been feeling for, films that make friction.

‘Some people are not interested in seeing reality. They paper over it, obscure it, pretend that there is nothing beyond what survives. Did the Celts have no inner life, because it is not written down? No. Is your history not real, because it is harder to find? No.’

Angie nods.

‘We bless you, strange angel, with the secret world’s sight. You will recognise what has been hidden from you, you will be drawn to your invisible kind. Your obligation, now, is to weave. Is to make yourself visible, so that your artistic descendants may see. Take from them the burden you carry, of a nostalgia for an unknown past.’

‘I understand,’ Angie says. The woman touches her forehead, parts her fingers, opening a third eye.

Find them, not just because they’re like her. Find them, these traditions buried and lost, because they are great lost works, surviving only in the hearts of those who had the fortune to see them.

There is a knock on the door. Angie stirs in her chair, the room back to normal, as if waking from a dream. The projector is still loaded, the reel at an end.

The door opens, and Molly enters. Blazing with a green halo, turned pastel and gentle, nourishing rather than painful to the eyes.

‘Hey, you didn’t say what room to find you in,’ she says.

Angie doesn’t remember calling, but knows she must have. She walks over to the projector, switching it for her updated reel, the ghostly tears re-appearing as a soft glow. Cut five. She loads it, the subtitle borrowed from Molly first.

‘Thanks for coming,’ Angie says. ‘There aren’t a lot of changes, but I wanted you to see.’

‘Oh, sure thing,’ Molly replies.

Pulling the thread, feeling for the edge. Vincent Price’s creature in the pit, always lurking but only now visible. The multi-coloured light, pulsing from her heart. More than human, like the beautiful monsters that dark-hearted girls like Molly write poems to

She also wrote social-realist screenplays, but they were never produced. Screened at local film festivals, but never picked up. A limited run of 300 DVDs. She submitted her work under a false name, and could never be tracked down.

Angie didn’t know where this would end up, but she could feel a first step. A first clue, a re-discovery, of these artists long buried alive.

AR Crow

Queer the Screen II

The urgency of the disco beat

the heartbeat

the fight

the fucking

when no-one knows how long it can keep going

how long any of this can keep going

or who will get beaten next.

Katy Perry Remix

I kissed a gay guy and he liked it

Amidst queer adolescence

the taste of validation

is stronger, sweeter

than any Jägerbomb

I lost my stuff then found it again

I lost myself then found him again

Jane Flett

Jellyfish

Leah started calling me Jellyfish because of the tattoo. She says that’s what it looks like — a big amorphous blob, all head and no heart. It’s her fault. It was supposed to be an actual heart, an extra one for the outside, because my first was all bunged up from not enough kissing.

I try, I try. I do. But there’s no one in this school both willing and worthy for these lips.

Anyway, after two-thirds of a bottle of Malibu, Leah’s hand was less steady than my own pounding chest, and the heart came out how it came out. She says I should be grateful. She read on the internet that mixing glitter with tattoo ink is a recipe for infection, septic sores, and skin cancer. She read it after we did it. You can’t really see the glitter sparkling under the skin, but the lines healed up well enough.

So Jellyfish is better than a septic sore. And sometimes, when I’m lying in bed at night, waiting for the suburbs to come down and crush me, I run my fingers over my second heart and whisper Jellyfish, Jellyfish, Jellyfish.

I feel my own tentacles wriggle, and I know I’ll get out of here soon.

The name caught on because people do what Leah says. She may not be in the cool clique, but she terrifies them, which is better. She brings a three-inch blade to biology and runs it up and down the inside of her calf when Mrs Massie’s not paying attention, holding the eyes of anyone who dares look at her the way a lioness might hold a kitten in her jaws. Her locker door is covered in Catholic iconography and crusted tampons nailed up with drawing pins. If anyone asks why, she says ‘spellwork’ and does that grin that shows all the way to her molar gold.

It’s because of her I get beaten up half as much as I used to. It’s because of her Jellyfish has replaced faggot as the nom du jour. We have a special relationship, one based in effigies of Marilyn Monroe, the Devil tarot card from the Raider-Smith-White deck, and a predilection for hardcore BDSM chatrooms.

‘Go on, go on, tell him you’re fourteen,’ she gasps, as I have the forty-eight-year-old stockbroker eating out of the filthy dogbowl of my hand. ‘Tell him you’re a boy.’

Sometimes I think she keeps me around because I am the most imaginative pervert she could find. Her own descriptions always fall flat, always stutter into some inane loop-the-loop of put it in, put it in again, hey keep putting it in and out and in again.

‘Not a boy,’ I say, and I tell the man I’ve lifted my tartan skirt up around the pudgy white flesh of my stomach. I say I’m holding the crucifix tight in my hand, the bulldog clips clamped tight on my poor innocent nipples. I describe the texture of the lard waiting by my twinkling pink asshole.

< I could put it in now. If you like? I’m a bit nervous :) >

No matter how Leah pleads, I refuse to use text speak beyond the occasional emoticon.

‘It’s more real!’ she says. ‘It’s what they expect.’

But even I’m not that perverse.

The truth is I love it as much as she does. Together we’re glamour whores and magicians, clad in sparkly rags and filthy intent. Through the internet, we can make anyone do anything. Take an old man and unwrap him and force everything we want into the dark passages that lurk in his own sack of skin.

< I’m tugging on the bulldog clip. It hurts . . . >

< thinking about how it would feel if it was your cock this sharp in my ass >

< oh ow. oh my god. ow.! >