1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

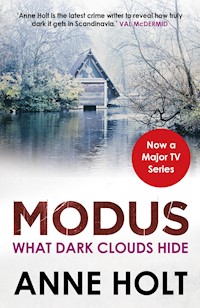

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The stunning conclusion to Anne Holt's phenomenal series featuring Johanne Vik and Adam Stubo. On a summer's day, Johanne Vik arrives at the home of her friends Jon and Ellen Mohr and was greeted by a scene of devastation: their young son, left unattended, has tragically fallen to his death. Meanwhile, Oslo is under attack. An explosion has torn the city apart and newly qualified police officer Henrik Holme is the only one available to attend the Mohr household. As Holme investigates, he casts doubt on the claim that the death was a tragic accident and calls upon Johanne's profiling expertise to understand what really happened. But neither realise that those involved are determined to hide the truth - no matter what. Before the summer is over, more shocking deaths will occur...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2017 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Originally published in Norwegian as Skyggedød in 2012 by Piratforlaget.

Copyright © Anne Holt, 2012 Translation copyright © Anne Bruce, 2017

The moral right of Anne Holt to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Anne Bruce to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

This translation has been published with the financial support of NORLA.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 84887 617 0 Paperback ISBN: 978 1 84887 618 7 E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 422 9

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

I

The boy lay on his mother’s lap as if fast asleep. He was too big for her: a strapping fair-haired lad, eight years old, stretched out across his mother’s scrawny thighs, with her arms round his waist and underneath his head, to hold it upright.

‘No,’ the mother said, almost inaudibly. ‘No. No. No.’

The boy’s left eye had disappeared into swollen tissue and dried blood.

‘No,’ the mother repeated.

Slowly, she raised her face to the ceiling and took a deep breath.

‘No!’

The scream filled the room so suddenly that the father took a step back. He held his head in both hands, a comical gesture underscored by turning to the wall and banging his head rhythmically on the pale wallpaper.

‘I should have kept a better eye on things,’ he groaned.

Thump. Thump.

‘It’s my fault. It’s all my fault. Keep an eye on things. Always keep an eye on things.’

Thump. Thump. Thump.

‘No!’ the mother screamed again.

The man turned to her once more.

Saliva dribbled from his lips. Blood oozed from one nostril, though he pretended not to notice. He allowed his arms to drop, his body crumpled inside the light-grey summer suit; he seemed to shrivel on the spot, allowing blood to drip on to his red tie and fade away.

Lowering her head to her son’s battered face, the mother attempted to pull his left arm across his body. It proved impossible. The arm was broken, apparently at the elbow joint itself.

A training shoe lay on the floor.

The other was still suspended from the boy’s foot, teetering from his toes; the blue, grubby shoe threatened to fall at any moment.

Size thirty-seven or thereabouts, Johanne Vik thought.

Eight years old and big feet. The heel and toe of his sock were worn thin.

‘No,’ the mother mumbled over and over again.

‘What happened?’ Johanne wanted to ask; she stood in the doorway trying to digest the scene that met her eyes.

The words would not come.

She forced some saliva into her mouth, smacking her lips and swallowing as she felt a faint vibration under her feet. A jolt, as if from a distant earthquake. Only for a second, and then it subsided.

Even the mother no longer uttered a sound.

‘What happened?’ Johanne eventually managed to ask.

‘I didn’t keep an eye on things,’ the father said, pointing with a limp hand to the stepladder in the middle of the spacious living room.

‘You didn’t keep an eye on things,’ the mother repeated mechanically into the boy’s bloodstained hair.

‘Are you sure he’s—’

Johanne tried to cross to the settee.

‘Don’t touch him!’ the mother yelled despairingly. ‘Don’t touch my little boy!’

‘We’re sure,’ the man said.

‘Then I think...’ Johanne began.

She should not think anything. Not think. Simply observe: the stepladder under a bare ceiling. No lamp up there, no hook, nothing to be righted or repaired: an out-of-place, high stepladder in a large, stylish, extremely tidy living room, where the dining table at the far end was all decked out for a party. Flowers everywhere. Wild flowers and garden roses in similar glass vases, and small posies between the place-settings on the table. Outside the picture windows the dull grey clouds hung low in the sky. Far below, in the city centre, Johanne could, however, make out a rising column of smoke, darker grey against the backdrop of the fjord in the far distance.

A living room decorated for a party.

A blue torch, she noticed, beside one leg of the stepladder, a dark-blue, large torch with Lightning McQueen painted on its side. A heap of old crayons: well used, grubby wax crayons piled up on the floor.

A dead boy.

The torch shed a beam of light.

Without entirely knowing why, Johanne stole a glance at the clock. It showed 15.28, and it was Friday 22 July 2011.

‘I must phone the police,’ she said softly.

‘The police,’ the woman whispered hoarsely. ‘What can the police do for my boy?’

‘It’s just that it has to be done,’ Johanne mumbled tonelessly. ‘I think that would be best.’

The truth was that she had no idea what else she could do.

Through the open verandah door she could hear sirens in the distance.

Lots of them. They seemed to be everywhere.

*

This was her fourth attempt. Johanne could not understand why the emergency number lacked sufficient staff to cope with a quiet Friday in the summer holidays.

‘Police emergency. What do you want to report?’

At last.

‘Hello. My name’s Johanne Vik.’

A momentary hesitation.

‘What’s it about?’ the woman at the other end of the line asked brusquely.

‘A death. A boy aged eight who—’

‘In the government quarter? Where?’

The woman on the line seemed agitated.

‘Do you see anyone from the rescue services anywhere nearby?’ she shouted.

‘No. The government quarter? I’m in Grefsen! At the house... I’m at my friends’ house and—’

‘In Grefsen?’

‘Yes.’

‘Whereabouts?’

‘They live in Glads vei.’

‘Professor Dahls vei?’

‘No, that’s not even in Grefsen!’

Johanne had gone down to the spacious hallway to make the call. Now she regretted that. The parents should not be left alone with the child. Should not be left alone at all. Slowly, as if doing something she really shouldn’t, she crept upstairs to the living room and dropped her voice.

‘I said Glads vei. G-L-A-D! Glads vei in Grefsen. A child has... There’s a dead child here. It looks like an accident, but—’

The call was cut off.

‘Hello?’ Johanne said.

No reply.

*

In the days that followed, Johanne often marvelled that she had actually been able to stand being there. Several times she had been obliged to leave the couple with the dead child on their own in the living room. The nausea that had overwhelmed her continually forced her out to the guest bathroom, accessed from the hallway. The first time she had to thrust two fingers all the way down to where she could feel her tongue rough and hard. Then sour bile and the remains of a hurried lunch spewed out automatically each time she leaned over the toilet bowl. The acid aftertaste was impossible to swallow, and the scent of jasmine no longer pervaded the bathroom.

The man and woman who had just lost their only child had sat down together on the settee. The boy was still stretched out on her lap. The father was permitted to place his arm round his wife’s shoulders, but every time he lifted his free hand to touch the boy, the mother again screamed: ‘No!’

Johanne was of no significance to them. They did not speak to her, and no longer replied to her questions. When she returned after her first visit to the toilet, the man had tidied the room. The stepladder was gone. The blood on the floor had been wiped away. The torch emblazoned with Lightning McQueen was nowhere in sight. Not the crayons, either. Johanne had been on the verge of tears as she again, and this time more insistently, reminded them that everything had to be left untouched until the police arrived. The man did not answer. Did not look at her. Did nothing other than sit stiffly beside his wife, staring at the boy.

Anyway, it was too late.

The living room was clean and tidy, as if still anticipating cheerful party guests in a few hours’ time.

If only it hadn’t been for the dead child.

‘No,’ the mother mumbled almost soundlessly.

Ten past four, and Johanne still had not made contact with the police.

‘Adam,’ she muttered, tapping in his number.

After six rings she was transferred to his answerphone.

‘Phone!’ she whispered. ‘You must phone me. Right away. Right away!’

She struggled to remember her own home number. The landline was hardly ever used now. Eventually her fingers found the correct digits.

After ten rings with no answer, she disconnected the call.

The iPhone on the mantelpiece suddenly made an ear-splitting noise. Neither of the couple on the settee seemed to react.

‘Is that yours?’ Johanne asked, trying to catch the woman’s eye.

‘No,’ the mother mumbled into the boy’s hair.

‘Ellen,’ Johanne said, crossing over to the fireplace, ‘can I take this?’

Without waiting for a reply that would never come anyway, she picked up the iPhone and placed her thumb on the display.

‘Hello?’

‘Hi, Ellen.’ A female voice continued breathlessly, ‘It’s Marianne here. I thought I should check with you whether it’s not best to cancel the party now that—’

‘This isn’t Ellen. It’s Johanne.’

‘Johanne? Did I misunderstand...? I thought we were to come at seven o’clock!’

‘Yes, that’s right. I’m here to... I was supposed to help, and then—’

‘Then this terrible thing happened. And so I thought...’

Johanne used her finger and thumb to pinch the bridge of her nose.

‘Yes,’ she said under her breath, turning her back to the couple on the settee. ‘It’s dreadful. Absolutely horrendous. But how could you know?’

‘My sister’s married to a Muslim,’ Marianne said at the other end. ‘Two children. Two dark-skinned children! What’s it going to be like in this country now?’

Her voice cracked.

‘Muslim,’ Johanne repeated in a subdued tone. ‘I don’t quite understand what...’

Marianne swallowed audibly, before clearing her throat and speaking in a loud voice: ‘In any case, I can’t come now. The right thing would be to cancel the whole affair. Can you just let Ellen know? People won’t be in the mood to reminisce about schooldays, when something like this has happened. In Norway. In Oslo.’

‘Of course there won’t be any dinner party, but what—’

‘In our city, Johanne. In our city!’

‘Marianne—’

‘Have you seen the pictures? On TV? There must be hundreds of people dead! And my sister who’s—’

‘Marianne,’ Johanne said, this time in a sterner voice. ‘What on earth are you talking about? What is it they’re showing on TV? What’s happened?’

‘Don’t you know?’

‘No.’

‘Don’t you know that someone has blown half the city centre sky-high? A huge bomb, Johanne! Terrorists, they say, Muslim terrorists, and what’s now...’

Johanne was no longer listening. She heard nothing.

She stood with her back to the fireplace and her gaze turned to the settee. Now she let her eyes wander in the direction of the window. Beyond the rain-soaked rose bushes in the garden and the shabby districts separating Grefsen from the city centre, before the leaden waters of the fjord, all the way down there, slightly to the east of the City Hall’s blunt tower, the column of smoke had grown in size.

‘You know who’s supposed to come tonight,’ Johanne said slowly.

‘Yes, I was the one who prepared the guest list. All the girls from 3B, except—’

‘Call them. Cancel.’

‘Can’t Ellen—’

‘Please.’

‘But my sister—’

‘Call them, Marianne. Cancel it. Please. Can I rely on you?’

The line crackled and Johanne repeated: ‘Please, Marianne.’

‘OK. All right.’

‘You were the one who didn’t keep an eye on things,’ Ellen sobbed from the other side of the room.

The call was disconnected.

‘Ellen,’ Johanne said as calmly as she could, taking a few steps over to the macabre tableau on the settee. ‘I don’t think there’s any point in—’

Her words were interrupted by a door slamming loudly, startling her. The brittle sound of broken glass from her own mobile phone as it hit the floor was followed by rapid footsteps from the hallway and a voice humming as it approached the living room.

‘Hi,’ a man said cheerfully, throwing his arms wide. ‘Are you ready, Jon? That doorbell of yours isn’t working, just so you know.’

The man could hardly be more than thirty. He ran his hand through thick, mid-length hair more sun-bleached than the weather of the past few weeks might suggest. His tight-fitting, pale-blue T-shirt emphasized the suntanned hue of his skin. He was still smiling broadly, and he scrutinized Johanne with rapidly diminishing interest, before taking a couple of steps across to the settee.

‘Hi there, Tarzan,’ he said, grinning, to the boy. ‘Shall we—’ He was brought up short. ‘What the blazes—’

‘No,’ Ellen murmured.

‘What the hell?’ the man said, panting. ‘Jon! Jon, for fuck’s sake, what’s wrong with Sander?’

‘Sander’s dead,’ Johanne said. ‘I’ve been trying to get hold of the police for ages, but they—’

‘Dead? What do you mean...? Don’t kid about! Jon! Answer me, won’t you? What’s wrong with you both? What’s wrong with—’

‘No,’ Ellen whispered.

‘I didn’t keep an eye on things,’ Jon reiterated in a monotone.

‘The police,’ Johanne said in a loud voice, picking up the shattered pieces of the mobile phone. ‘We need to get hold of the police, but they’re obviously busy with this...explosion in the city centre.’

‘Explosion?’ the man echoed. ‘What explosion? What has happened to Sander and what—’

He raised one foot to step towards the settee, but changed his mind, instead standing transfixed.

Johanne took a deep breath.

‘We need to get in touch with the police,’ she said yet again. ‘But there’s obviously been a major...event in the city centre, so they’re busy dealing with that. I suggest that you...’

She stared at the young man.

‘Joachim,’ he said huskily. ‘My name’s Joachim. Jon, Sander and I were to... I mean, Ellen was holding a party, you see, and we—’

He was unable to continue. Johanne could see that his blue eyes were welling up with tears and he found it impossible to wrench his gaze from the dead boy.

‘You stay here,’ she said. ‘Don’t move anything. Don’t touch...Sander. I’ll go down to the kitchen and phone all the police personnel I can think of. I’ll borrow your phone, Ellen.’

The boy’s mother did not reply.

‘Stay!’ Johanne said sharply to all of them, as if speaking to a pack of unruly dogs. ‘Stay here, and don’t touch anything.’

With a broken mobile phone in one hand and Ellen’s iPhone in the other, she headed for the door. A faint whiff of aftershave brushed her nostrils as she passed Joachim. It smelled expensive, and he had an exclusive cashmere sweater slung over his shoulders, knotted at the front.

Fifty-five minutes had passed since her arrival.

And in the distance, to the south, the sirens wailed incessantly.

*

The police officer’s uniform was too large for his skinny frame. His hair was thick, blond and recently cut, above a smooth face with child-like red lips. His Adam’s apple bobbed up and down in a rhythm that, in other circumstances, would have made Johanne laugh. The black epaulettes with single gold star informed her that he was a constable. Newly graduated from Police College, was Johanne’s guess. Not exactly what she had been hoping for, but better than nothing.

Or perhaps not.

‘What has happened here?’ he asked, looking at Johanne as his left forefinger twice rubbed the side of his nose before he somehow stood stiffly to attention again.

‘I don’t know. When I got here, round about quarter past three, the boy was dead.’

‘I see.’

The young police officer now fixed his eyes on Joachim, leaning against the fireplace with his arms folded across his chest.

‘I came even later,’ Joachim said dispassionately. ‘I don’t know anything.’

‘Well then,’ the policeman said, swallowing.

Silence descended on the room. Joachim had closed the verandah door some time earlier, and it was no longer possible to hear the sirens in the city. Only Ellen’s monotonous sobbing, interspersed with the occasional ‘No’, broke a silence so oppressive that Johanne felt perspiration trickle between her shoulder blades. The policeman continued to stare at her, as if he expected her to speak up, to take charge, to put things right. It felt uncomfortable.

‘The boy,’ she suggested sotto voce, looking at him. ‘He’s called Sander. He should really have a post-mortem. It’s normal procedure.’

She tried to sound more certain than she felt.

‘Yes,’ he said, nodding. ‘We need to arrange for an ambulance.’

‘As far as I understand, they’re all spoken for.’

‘Yes. The explosion, of course.’

Nodding, he stared at the boy, still lying on his mother’s lap. The Adam’s apple continued to bob up and down.

‘I can drive him,’ Joachim suggested hesitantly. ‘It’s at the National Hospital. Isn’t it?’

‘I guess so,’ the police officer said, drawing his words out as he scratched his neck with a sharp index finger. ‘Grefsen does come under Ullevål, I suppose. I think maybe—’

What he thought never became quite clear.

Yet another man entered the living room.

‘I rang the doorbell,’ the new arrival said. ‘Since no one answered, I came right in. I’m Kalle Hovet!’

He offered his hand to the young Constable, who accepted it diffidently.

‘Police Prosecutor Kalle Hovet,’ he explained succinctly. ‘My colleague Silje Sørensen called and asked me to come here. I live in Kjelsås, just close by. She had received a phone call. From you, I assume?’

He looked at Johanne, who nodded. When no one else could be contacted and Adam still had not returned her call, she had phoned the one person in the Oslo Police Force she knew best. Silje turned out to be on holiday in the Bahamas, with no knowledge of what had taken place in Oslo city centre, but she had obviously phoned round all the same.

‘Our officers are, as you understand...’

His fleshy fist briefly indicated the picture window.

‘...busy. Extremely busy.’

‘What’s happened down there?’ Johanne asked softly.

‘Don’t exactly know. Although it’s not normally part of my daily routine to turn out like this, all the same—’

Again he interrupted himself. His eyes flashed around the room and came to rest on the family group on the settee. He blinked, as if having problems with his eyesight.

‘A fall?’ he enquired.

The parents did not answer.

‘Yes,’ Johanne replied, with a nod. ‘As far as I can make out, he fell from a stepladder.’

‘What stepladder?’ Kalle Hovet asked, without taking his eyes off the boy.

‘It’s...it’s been moved.’

‘Moved?’

‘Yes,’ Johanne answered, barely audibly. ‘I’m afraid this scene is...not really... It’s obvious that it was an accident. Sander’s a boy who—’

The burly, middle-aged man raised his hand.

‘Listen here,’ he said, mostly for the benefit of the uniformed officer. ‘We’re not exactly experts, any of us. Not in this kind of thing. I’ll try to get a crime-scene technician to attend sometime this evening. Meanwhile, I want everybody out of here. There must be a basement room, or some such place, in this enormous house.’

He ran his hand over his scalp, where the hairline had receded into a shiny bald patch.

‘And the boy must be taken to hospital,’ he said, sounding despondent. ‘How we’re now going to—’

‘No!’ Ellen shrieked. ‘No! No!’

She got up from the settee, still with the bulky eight-year-old in her arms. She staggered as she walked past the small glass coffee table, across the pale carpet and over the parquet flooring, where she filled her lungs with a deep breath before screaming piercingly one more time: ‘No! Don’t touch my boy!’

Before anyone was sufficiently composed to offer her assistance, the boy slipped slowly from his mother’s grasp.

She could not take it any more.

‘No,’ Johanne whispered, but it was too late.

*

‘What a story,’ Kalle Hovet commented and inhaled deeply on his cigarette.

‘Down there or up here?’ Johanne asked, side-stepping to distance herself from the smouldering roll-up.

The Police Prosecutor held the smoke in his lungs for several seconds before blowing it out lingeringly through his nose.

‘Both of them, you might say. Although I’m somewhat under-informed about what’s actually taken place in the city centre. A real bomb, is what I was told before I came here. They’re talking about a terrorist attack. Outside the Verdens Gang newspaper offices, or something like that. Don’t care much for that rag anyway, but there are limits. I was bloody tempted to switch on the TV in there, but that wouldn’t have looked too good. Do you know anything more?’

It was now twenty minutes to seven. They were standing on a paved patio on the south-east side of the large villa, a few metres from the front door. The young police officer had finally made contact with the funeral directors, for lack of anyone better. When two solemn old men who looked like twins, dressed in dark suits, white shirts and narrow black ties, arrived to convey the disfigured corpse of eight-year-old Sander Mohr to the National Hospital, scenes had played out over which Johanne even now was struggling to draw a veil of forgetfulness. In the end, Ellen had gone with them in the car, crouched over her dead child, who had now lost two front teeth when she had dropped him on the floor. Joachim, whom Johanne had eventually learned was a younger colleague of Jon’s and obviously a friend of the family, had offered to accompany them to the hospital, in order to bring Ellen home again when that time came. If it proved at all possible to tear her apart from the boy, Johanne thought. Jon stared silently out of the kitchen window while the police officer posted himself on the opposite side of the table, waiting for reinforcements. Something that might take some time.

Johanne was aware of a faint, unpleasant sense of her feet not quite being planted firmly on the ground.

‘No,’ she said. ‘I’ve no idea. And now I can probably go.’

‘Do you know them?’ Kalle Hovet nodded at the house.

‘Yes. Ellen and I went to high school together.’

Johanne did not elaborate. Something was bothering her. She closed her eyes and could recall every detail in there with precision, right down to the pattern on the silver cutlery. The sheer curtains and their woven, almost invisible motif of oak leaves. The oil painting above the fireplace, with a tiny crack in the lower left corner, as if it had fallen on the floor at some time. The soap dispenser in the bathroom that had recently been filled to the brim; she had spilled some soap on the basin when she washed her hands and had been overwhelmed by nausea again, because of the heavy floral scent.

Even the hallway, that extensive space where shafts of light fell through rectangular windows facing north-east along the ceiling, and the kitchen, where she had mainly concentrated on contacting someone in the police force, she could re-create in detail in her memory. There was something she should have noticed. Something that had changed, been altered, though it had nothing to do with the stepladder or the torch.

‘Yes,’ she said, opening her eyes. ‘Ellen and I went to high school together. Jon as well, for that matter, but I’ve become better acquainted with him since then. But we’re not...’

She had to think about what they were and what they weren’t.

‘Not really friends. Not now, I mean. We’ve probably seen each other two or three times a year for quite a long time. Maybe not even that. Casual acquaintances, you’d probably call it. I was to come a bit earlier than the others to lend a hand, but also to... Well. Catch up, in a way.’

‘That’s how it is,’ Kalle Hovet said with a smile. ‘Life goes on, and it just snowballs – marriage and children and career, and hey presto!’

He snapped the fingers of his free hand and took another deep draw on his cigarette.

‘Then you’ve hardly any friends left. If you don’t keep an eye on things.’

If you don’t keep an eye on things, thought Johanne.

‘That’s what they were saying the whole time,’ she said.

‘What’s that?’ Kalle Hovet asked.

‘They were blaming each other for not keeping an eye on Sander.’

He tossed the cigarette butt on the ground and trampled it emphatically into the gravel between the paving stones.

‘That’s how it goes,’ he answered. ‘When senseless things happen, we blame each other. It gets too hard to take the responsibility alone, I expect. Even harder to appreciate that things just happen, sometimes. That life doesn’t come with any guarantees. Bloody hell!’

The last comment was spoken in a whisper. He stood up straight and stared out across the city.

‘I just can’t imagine what it must be like. To lose your child.’

Suddenly he turned on his heel and caught her gaze. His eyes were yellowish-brown with heavy, dark eyebrows that met above the bridge of his nose.

‘Do you have children?’

‘Yes. Two daughters. A seventeen-year-old and one aged seven and a half. Kristiane and Ragnhild, they’re called.’

A sudden gnawing feeling inside made her gasp for breath.

‘They’re on holiday with their father. The father of the eldest, that is. The father of the younger one’s a different... They get on best when they’re together, the children. Kristiane’s not quite like... like other children, and my ex-husband prefers it if they both—’

She tucked her hair behind her ears in a nervous gesture. Amazingly enough, she had started to talk to this man about things that had nothing to do with him. There was something about him. Something unusually friendly, tired and maybe even a little worn out. He reminded her of a Danish actor whose name she couldn’t remember.

She wanted to go home. Johanne wanted to go home to Hauges vei, she wanted to phone the children and, besides, she wanted to find out what had become of Adam. He had said he would spend his night off, which was what he called it, irritatingly enough, putting up some new bookshelves in Kristiane’s room and watching a DVD that didn’t remotely interest Johanne.

Besides, there was that explosion.

Marianne had probably been exaggerating enormously, as she always did, but the column of smoke down there was still hovering like an amorphous tube, at a slight angle above the city. An accident, possibly.

Gas. Something like that. It couldn’t be a terrorist attack, as the Police Prosecutor had suggested. Not here. Not in Norway. An accident. There might be extra bulletins on TV all the same, since there was so little news during the summer holidays.

‘You know how it is,’ she said, adjusting her shoulder bag as a sign she wanted to leave.

‘Don’t I know!’ the man exclaimed, smiling. ‘My wife and I have seven children in total. Only one of them together. It’s like a madhouse on the weekends when they’re all together. Not to mention the holidays. By the way, I wonder if it’s going to rain for the whole of this damned summer?’

The man cocked his head and glanced up at the sky. Then he looked at her again with a quizzical expression, as if he really wanted a response to his observations about the weather.

It struck Johanne that this entire situation was inappropriate. Here they were, making small talk as if a party was actually in progress inside. As if the dinner would be ready any minute, and she had simply joined him outside in the garden out of politeness, to give him the opportunity of a semi-forbidden smoke.

‘Relax,’ Kalle Hovet said, unruffled.

His eyes were actually more yellow than brown, she thought.

‘We’re both upset. This is just a way of—’

He flung out his arms expressively, before running both hands over his head.

‘Fucking awful,’ he murmured. ‘In there, that was totally and completely fucking awful. You think you’ve got everything dangerous under control. You install child safety-locks and gates, equip them with helmets and car security seats, and all possible things. Then you turn your back for a couple of minutes and... A stepladder. A bloody stupid stepladder. By the way, are there any other relatives we ought to contact? Someone who could help Ellen and Jon? Parents – that is to say, the child’s grandparents?’

‘His father’s father is dead,’ Johanne said, giving the matter some thought. ‘His father’s mother is called Helga Mohr and, as far as I know, she was close to the boy. As far as Ellen’s parents are concerned...’

Johanne remembered them well. In their teenage years, Agnes and Torbjørn Krogh had been the parents everyone in Ellen’s circle of friends envied. Their door was always open, and they were cheerful, welcoming and fairly youthful themselves, without seeming pathetic. Ellen was an adored only child, and the relationship appeared to be mutual. But something had happened. Something that Johanne had never quite grasped. Three years ago, when Agnes and Torbjørn had not turned up at the traditional summer barbecue in Glads vei, Johanne had asked Ellen whether they were away on holiday. Ellen had not given a direct answer, and had simply mumbled something about them no longer being welcome. Later Johanne had gained the feeling that it all had something to do with Sander’s upbringing. Ellen would not talk about it, and Johanne did not feel close enough to her to delve deeper into something that was really none of her business.

‘I think his mother’s parents are out of the picture.’

Hovet’s mobile phone vibrated almost soundlessly in the inside pocket of his light summer jacket.

‘That’s the tenth time in the past half-hour,’ he said resignedly. ‘At least. With seven children, there can be a lot of bloody hassle. I felt I couldn’t really answer while the boy was lying there and his mother was so—’

Fumbling in his pocket, he extracted a Nokia and opened a text message. Johanne turned to face the wide set of eight steps that led up to Glads vei.

‘What the hell,’ she heard him mutter as she started to leave. ‘What in—’

When she turned to him again, he had grown visibly paler. The hand that held the mobile phone was shaking, and he was obviously reading the message several times over. Or maybe there were several messages. When he finally met her eye, his mouth was open and his expression disbelieving, as if he could not take in what his brain was struggling to process. It reminded Johanne of a roe deer she had once knocked down in the dark: the terrified, confused eyes she glimpsed as they reflected the headlights, before the car struck the animal and it died.

‘What is it?’ she said tentatively, stepping towards him.

Kalle Hovet did not answer. Instead, he took off at full pelt. His shoulder hit her and almost knocked her off-balance as he passed, taking the steps three at a time.

Without uttering a word.

Johanne heard an engine start and tyres screech on the asphalt as the vehicle accelerated down the street and disappeared into the distance.

Perhaps this explosion was worse than she had supposed.

She tried in vain to revive her broken mobile phone. She wanted to check on the Internet what this was in fact all about. The display lit up behind the broken glass, but there were no icons. With a sigh, she stuffed the phone back in her bag and glanced at the kitchen window.

Jon was staring out at her. His face appeared flat and shapeless through the glass, as if someone had tried to erase it, without quite succeeding. Only the thick streak of dried blood between his nose and top lip was clear and distinct. Behind him she could discern the tall, gangly policeman, motionless as he waited for someone it seemed would never come.

She turned abruptly and headed for the paved steps, edged on both sides with low rhododendron bushes that lacked blooms. The steps were wide and deep, and on the top step she spotted a hard plastic fire engine, about thirty centimetres in length. Johanne stopped with one foot on each step.

It was Sulamit.

She picked it up.

Of course it wasn’t Sulamit. The fire engine that Kristiane had owned throughout her childhood and, oddly enough, had referred to and addressed as if it were a deeply loved cat, had died a long time ago. The ladder and wheels had gone first, and after that all the other loose parts, before the paint itself had faded and finally disappeared. When all that was left of the toy engine was a grey scrap of metal, even Kristiane had understood that there was no life left in her sort-of pet cat. Now it was buried in the tulip bed facing Hauges vei, beneath a small wooden cross with ‘RIP Sulamit’ in pink letters that were repainted each spring.

This toy was exactly the same as Kristiane’s one-time dearest possession.

The same eyes were painted on the front headlights; the same silver ladder and the oversized shiny black wheels. Compartments could be opened on either side, but the hoses and the smoke-diver apparatus were things that Johanne had forgotten.

‘Sander,’ she whispered to the fire engine as her eyes filled with tears. Little, big, strange Sander.

She carefully replaced the toy engine on the step, tucked in at one side, half-hidden beneath the thick, dark-green rhododendron leaves. The paint was luxuriant and shiny, and the merry eyes looked diagonally up at her, a toy that had outlived its owner.

She rushed away.

She ran home in her low-heeled shoes, with her umbrella under one arm and a dainty evening bag over her other shoulder. Only when she was worn out, with one shoe threatening to form a blister on her heel, did she slow down and notice how still everything was. No people out of doors. No smell of charred meat from patios and terraces where barbecue grills sheltered under porch roofs from the rain – the endless rain that would soon stop spoiling the summer of 2011. The children she had seen on bicycles and football pitches on her way to Ellen’s house had vanished. Through the odd window in the apartment blocks in Betzy Kjelsbergs vei, Johanne could see television sets flickering soundlessly in the damp evening light.

Only the dull flapping of a distant helicopter, out of her range of sight, broke the strange silence over Oslo. Maybe there were two of them. Or three.

She broke into a run again.

*

It would soon be four o’clock on 23 July. The day was just dawning outside the windows, with barely half an hour until the sun would rise from behind the cloud cover that was still suspended above the city.

‘Mum,’ Johanne whispered, nudging her mother, who was snoring softly beneath a blue woollen blanket at the other end of the settee. ‘You have to wake up. There’s a press conference.’

Jack, the family’s golden-grey mongrel, got up from the floor and circled three times on arthritic legs before flopping down again with a sigh.

‘Why are you whispering?’ her mother murmured, struggling stiffly into a sitting position. ‘I wasn’t asleep. Just closed my eyes. What did you say?’

Johanne did not reply. Instead, grabbing the remote control, she increased the volume on the TV set and tucked her legs beneath her on the settee. Her mother laid a dry, warm hand on hers.

‘It was so good of you to phone me,’ she said quietly. ‘I’m really pleased you did, sweetheart. After all these dreadful things, I tried to call you at least ten times. I wasn’t to know that your phone was broken, of course. People shouldn’t be alone at times like these. And certainly not when all this about little Simen came on top of all the rest.’

‘Sander. Not Simen.’ Johanne tried to smile.

When she had arrived home the previous evening it had taken a few minutes in front of the television for it to begin to dawn on her what had happened in the government quarter of the city centre, and later on the island of Utøya. She had made a number of fairly desperate fresh attempts to get hold of Adam. He had left an almost illegible note on the dining table, saying that he had to go to work in connection with a terrorist attack and had no idea when he would be back. She could not really understand how a Detective Inspector in the Norwegian Criminal Investigation Service, the NCIS, who mostly sat in an office or an interview room, could be of any use, given the way the catastrophic afternoon and evening had unfolded. He often complained about it himself, especially after a couple of glasses of wine: Adam Stubo was becoming a pen-pusher. At one time he had been considered the best police interviewer in the country. After once again allowing himself to be persuaded to accept a leadership post, a great deal of his job satisfaction had been swallowed up by paperwork, trade-union demands and budgets, and he frequently moaned about it. Johanne had tried to contact him on both his mobile phone and his office number. She had even called five of his colleagues, without reaching any of them.

By the time she gave up, ten deaths had been announced on Utøya.

She had phoned Isak, the man she had been married to a lifetime ago and who, last Sunday, had taken Kristiane and Ragnhild with him to Sainte-Maxime for three weeks’ holiday. Of course he had not taken a phone with him, either. Johanne had thought of phoning her sister, but the idea evaporated as quickly as it had arisen. They had not seen each other for six months, and this was hardly the time to patch up a sibling relationship that, to be honest, had hirpled along since early childhood.

Without really considering it deeply, Johanne had finally dialled her mother’s number, who had answered the call after three rings, declaring calmly that she would come as quickly as she could.

Her mother had really changed after she had been widowed one January night exactly six months earlier. As usual, Johanne’s father had taken one drink too many before falling asleep beside his wife of forty-six years, in his winceyette pyjamas and bedsocks, but never woke up.

Johanne had constantly worried that her mother would be left on her own. The thought of having a somewhat confused father to look after seemed less frightening than having her bustling, neurotic mother at her door more often than before. But something had happened. Even when she arrived with the message about her father’s death on the morning of the day that Ragnhild turned seven, it was as if her mother was a different person. So self-possessed and sensible, Adam had said that same evening. More like resigned and devastated by grief, Johanne had responded. She had died a little, she thought, as if the symbiosis between her parents had been quite literal and the seventy-three-year-old woman was now merely half-alive.

It did not pass.

Johanne’s sadness over her father’s death had quickly been submerged by astonishment at the person her mother had become. After the funeral, Johanne had dutifully offered to let her stay on with them. For a while, she had said, just until the house at home no longer seemed so empty. Her mother had refused vehemently, packed her suitcase and insisted on driving home in her own car.

Something in her mother had been extinguished, and Johanne secretly felt guilty because she liked her better like this. As winter slipped away and spring and then summer arrived, her mother slid into a solitary existence that Johanne could hardly have anticipated. She phoned less frequently, and never turned up in Hauges vei without being explicitly invited. Her mother had always been brilliant with the children, patient and loving, and it was as though she now treated them all like children. Rather indulgently, with a little smile at everything that she would once have resisted with endless, futile arguments. She had even stopped complaining about Jack’s moulting.

Her mother gently shook a thermos flask. The scant rustling encouraged her to head for the kitchen to make more coffee.

‘Where on earth is Adam?’ she asked.

‘God only knows,’ Johanne answered distractedly, pushing his note underneath a newspaper. ‘But as things stand, I can’t really hold it against him. Now at least they’ve caught that damned terrorist, and maybe he— Shh!’

Her mother filled the coffee machine with fresh water and ground coffee and tiptoed back.

The newly appointed Police Commissioner could only just have managed to obtain a uniform for himself. As far as Johanne was aware, he had been in the post barely a week or so before the start of the summer holidays. His voice seemed deeper than Johanne remembered from the nineties, when he had been a politician.

The news was even more depressing.

‘Eighty,’ her mother whispered, covering her face with her hands.

‘Eighty!’ Johanne repeated with a short, sharp cry.

She could not recall when she had last shed tears in the presence of anyone else.

Not even at her father’s funeral had she given way to the hard lump of sadness at the lost opportunities for reconciliation with a father for whom she had felt nothing but a trace of contempt for far too long. Now the floodgates opened. She leaned half-reluctantly, half-searchingly towards her mother, who embraced her, rocking Johanne tenderly from side to side as she whispered little meaningless words of comfort.

‘I’m crying because...’ Johanne sobbed, but could not go on.

‘I know,’ her mother said softly. ‘Just cry.’

But her mother did not know. She had no idea that just at that very moment Johanne – stunned as she was by the events of that night – had lost control of herself over something quite different from the grotesque crimes in the government quarter and on the island of Utøya. The death toll from the double catastrophe was still too unreal. It was too late at night, too early in the morning, with too many individual fates to take in.

Instead Johanne was weeping over one in particular.

She was crying for a boy whose parents had not succeeded in keeping him alive for more than a mere eight years. Johanne shed tears for Sander, the big, cheerful, intense boy who had so recently been given a fire engine that he would never have a chance to destroy.