9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ONE

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

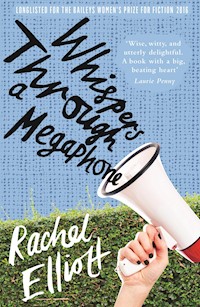

Miriam hasn't left her house in three years, and cannot raise her voice above a whisper. But today she has had enough, and is finally ready to rejoin the outside world.Meanwhile, Ralph has made the mistake of opening a closet door, only to discover with a shock that his wife Sadie doesn't love him, and never has. And so he decides to run away.Miriam and Ralph's chance meeting in a wood during stormy weather marks the beginning of an amusing, restorative friendship, while Sadie takes a break from Twitter to embark on an intriguing adventure of her own. As their collective story unfolds, each of them seeks to better understand the objects of their affection, and their own hearts, timidly refusing to stand still and accept the chaos life throws at them. Filled with wit and sparkling prose, Whispers Through a Megaphone explores our attempts to meaningfully connect with ourselves and others, in an often deafening world - when sometimes all we need is a bit of silence.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

WHISPERS THROUGH A MEGAPHONE

Rachel Elliott

To my family, shore to my sea

“When you decide to live, to finally live, a world of possibility opens, maddening and vast, but where is the bridge across to that world, can anyone see a bridge?”

MIRIAM DELANEY

Contents

1

THE SUPERABUNDANT OUTSIDE WORLD

Miriam Delaney sits at her kitchen table and watches the radio. She is mesmerized, transfixed.

Inside a studio somewhere—somewhere in the outside world—a woman is speaking in the fullest of voices about her extraordinary life: the adventures, the flings, the lessons she mined from her mistakes. Her stories are punctuated by music, carefully chosen to reveal even more life.

Miriam takes a deep breath in, because maybe what’s on the air is also in the air, maybe something of this woman’s superabundant presence will transmit through the broadcast.

Fancy being able to speak like that.

Fancy being able to speak properly.

It’s three years today since Miriam last stepped out of this house.

No, that’s not quite true. She has stepped into the back garden to feed the koi carp, stepped into the porch to collect the milk and leave a bin bag for her neighbour to place at the end of the drive. But step out into the street? No chance. Risk collision and a potentially catastrophic exchange with a stranger? You must be joking. Not after what happened. Not after what she did. Inside the cutesy slipper-heads of two West Highland terriers, her feet have paced the rooms of 7 Beckford Gardens, a three-bed semi with a white cuckoo clock, brown and orange carpets, a life-size cut-out of Neil Armstrong.

Miriam’s hibernation is three years old today, but numbers can be deceptive, three years can feel like three decades. Hibernation ages like a dog, so three is about twenty-eight, depending on the breed, and this one is kind, protective, it keeps the world at bay.

The world—now there’s an interesting concept. Miriam rests her chin on her hands. Where is the world exactly? Is it inside or outside? Where is the dividing line? Am I in or am I out?

She tosses a coin. Heads I could be part of the world, tails I’ll always be outside it.

The ten-pence piece, flat on her palm, says heads. Best out of three?

Three hopeful heads, one after the other.

Miriam smiles. It’s time. She knows it and the coin knows it. Show me the money. Money talks. It’s time to get a life.

The main problem? Other people. They have always been the problem. Other people seem to know things. They know what a life should contain, all the simple and complicated things like shopping and Zumba and being physically intimate with another body. They know the rules, the way it’s supposed to go. Miriam is thirty-five and when she looks out of the window all she sees is a world full of people who know things she will never know.

The world again. After years of not looking it’s all she can see. She would like to be part of it, to somehow join in.

She writes a plan on a Post-it and sticks it to the radio:

Do something I am afraid of. Apparently this builds confidence (have yet to see evidence of this—will be an interesting experiment)Spend next few days clearing out house—get rid of mother’s thingsLeave house next weekThe trouble with number one is what to pick from the enormous list? The task of actually making the list of things she is afraid of could take another month, and four more weeks inside this house? Four weeks that will feel like ten months? That thought is unbearable, it makes Miriam shiver and run upstairs to fetch one of her many cardigans.

But lists are good, remember? You can add things and take them away. Adding makes you feel like a person with clear intentions, subtracting feels like a small victory. What else? Well, a list is a personal map. It’s a ladder that you can move up and down at your leisure. When you cross things off it feels like you’re moving, you’re getting somewhere, there is some purpose to all this—something is finally happening.

Back in the front room, she begins the list.

Write fast, Miriam. You can do this. Lists are good. Write until you land on something you could tackle tonight. No, not tomorrow. Tonight.

THINGS I AM AFRAID OF

Idea that my mother is still alive somewhere and I am not aloneIdea that my mother is definitely dead and I am aloneGoing back to where it happenedLoveNo loveClothes shoppingThought that I might do it again if I go back outsideBeing stuck in a lift with a group of talkative peopleNever being able to write a list or letter due to major accident involving handsTurning into my motherHaving no capacity to know that I’m already just like my motherFingerless glovesNaked cleaningThere it is, number thirteen on the list (unlucky for some). Naked cleaning—all it actually requires is removing this cardigan, this T-shirt, these jeans, pulling Henry the hoover from the cupboard and plugging it in. How scary can it be?

Answer: that depends on your childhood.

It depends on whether, at the age of eight, you found your mother sweeping the floor of the school corridor wearing nothing but a pair of trainer socks. (Had she planned to go for a run and slipped into insanity seconds after putting on her socks? Can madness descend that quickly, like thunder, like a storm?) There she was, Mrs Frances Delaney, quietly sweeping her way through a turbulent sea of hysterical children, the waves of laughter rising up and up and—

Miriam was drenched. She had wet feet, wet hands, wet eyes.

Mother here at school. Mother naked. Other children cackling, jeering. Poor mother. I love mother and hate mother.

The headmaster appeared. He walked on water. He took off his suit jacket and smothered Mrs Delaney’s nakedness. He was gallant, unfazed. Perhaps he had seen it all before. (Miriam hoped not.) Frances carried on sweeping—she was thorough, if nothing else. She had always valued cleanliness and order. Perhaps the headmaster understood this, hence his sensitivity. Perhaps he respected it.

What made the situation worse, even harder for Miriam to comprehend, was the fact that her mother didn’t even work as a cleaner. Turning up at your own workplace without any clothes on is a rupture of social etiquette, a glitch in mental health, forgetfulness at its most perverse, but at least it contains a thread of continuity: I have done what I normally do, I have come to the right place, but something is amiss. I wonder what it could be? Turning up at someone else’s workplace—your daughter’s school—in the nude, in the buff, apart from tiny socks, is unbearably nonsensical.

Miriam’s mother was mad as a spoon.

Was it catching?

(Miriam hoped not.)

Fast-forward twenty-seven years and what do we see? We see a woman, carefully folding her clothes and placing them on the sofa. She walks to the cupboard in the hallway and pulls Henry the hoover out into the light, plugs it in, switches it on. Now she is vacuuming the brown and orange carpet in her front room wearing nothing but knickers and Westie slippers. A cuckoo springs from its house, making her jump. It’s ten o’clock. Only two hours left until Wednesday becomes Thursday, until the first day of August is over, and then it will be three years and a day since she ran all the way home, whispering oh my God, oh my God. Anniversaries come and go. Important dates get sucked into the vortex and life rolls on, taking us with it, perpetual tourists who pretend to be at home.

Steady on, Miriam. There’s no need to start brooding over the nature of existence. You’ve got to stay focused, just for once, otherwise you’ll never leave this house. Self-soothe, remember? Remember what the book said, the one Fenella lent you, the one about staying sane in a mad world.

Fenella Price. Chief supplier of objects from the outside world: food, pens, knickers, etc. Fenella is no ordinary friend. She is a Beacon of Sanity, forever glowing, her equanimity unshakeable. She is proof that people can be sensible, rational, consistent. But more importantly, she is proof that Miriam isn’t contagious. Her mother’s madness is in her blood and her bones—it has to be, doesn’t it? But Fenella has been there and seen it all, the highs and lows, the dramas and trips, ever since they were at primary school, and still she is sane. She wears smart clothes, works as a cashier in the local branch of Barclays, goes to evening classes three times a week: Pilates, Tango, How to Make Your Own Lampshades. As sane as they come, surely?

“Stay sane in this mad world,” Fenella said. “When your thoughts race off into historical territories, talk softly to yourself. That’s what I do. I don’t care where I am. I say just you settle down, Fenella Price. Everything is fine.”

Miriam sighs. Thank goodness for Fenella. If only she could tell her the truth about the thing that happened, the thing she did, three years ago today.

It happened like this.

Oblivious footsteps along the woodland path.

Oblivious footsteps across the field and all the way to the pub.

Lunch with Fenella (a cheddar and onion-marmalade sandwich, a few French fries, half a cider).

A hug and a goodbye, nice to see you, give me a ring soon.

Now we travel in reverse.

Oblivious footsteps across the field.

Oblivious footsteps along the woodland path. Disgustingly ignorant, outrageously unaware, until—

The world is a safe place until it isn’t.

People are good until they’re not.

Miriam wishes she had taken a final look at the buildings, the trees, the dogs playing in the field, but you never know what’s coming, you walk small and blind, the world simply an echo of your own concerns.

2

MOVE OVER DARLING

Ralph has Treacle all over his legs, his arms, his stomach. Treacle the ginger cat, bored with Ralph’s inactivity, hungry for breakfast. She pads up and down the sleeping bag, treads over the lumps and bumps of her new owner, searching for signs of life.

Treacle had been lost and alone, a stray cat in the woods, patchy and thin. Then she met Ralph Swoon, who was also lost and alone. Now they had each other, and a rickety old shed in the middle of the woods, full of slatted light.

He bought her a can of pilchards.

It was a fishy kind of love, but it was real.

Still wearing yesterday’s clothes, Ralph steps out of his sleeping bag. He runs his fingers through his hair and opens the door, heading for the pile of leaves that has become his outside toilet. Treacle sits in the doorway, waiting. She is already used to this part of their daily routine. She knows that Ralph will stumble back in, tip some food onto that cracked blue plate on the floor, then return to his sleeping bag and invite her inside it. Yesterday they fell asleep like that for three hours, with Treacle opening her eyes every now and then to make sure Ralph was still breathing.

Feline logic told her that he had dragged himself here to die. Why else would he have turned up in the woods at 11.30 p.m. on 4th August with no bag, no possessions, just a wallet, a phone and a guitar?

But the cat was wrong.

He hadn’t come here to die.

Last week, Ralph was sitting at the breakfast bar in his kitchen, listening to his wife and their two teenage sons out in the garden. Sadie and Arthur were hosing the legs of their new puppy while Stanley watched.

“This dog stinks,” said Arthur.

“It’s just mud. Help me hose it off,” said Sadie.

“He’s your dog, Mum.”

“Don’t start this again.”

“Who went and got him?”

“I bought him for you and Stan. You always wanted a dog.”

“I wanted a dog when I was six. You’re ten years late.”

“Oh fuck off.”

Arthur smirked. The puppy wriggled about, trying to escape the cold water, trying to play.

Ralph had been against the idea of a dog. Didn’t they have enough problems, without attending to the needs of what was effectively a furry baby? As usual, Sadie won. She said it would be good for Arthur, who was showing signs of excessive boredom. It would relax him, teach him responsibility, get him outdoors. A teenager needs a reason to climb out of bed in the morning, she said, otherwise he will sleep all day and all night and life will pass him by like an unremarkable dream. Sounds familiar, thought Ralph.

“Don’t get water in his ears,” said Sadie. “Dogs hate water in their ears.”

“So why does he keep jumping in the river?”

“Spaniels like to swim. They don’t swim underwater.”

Arthur dropped the hose on the floor. “He’s clean now, I’m going in.”

“He’s not clean. Look at him, he’s filthy.”

While the puppy shivered between them, Arthur and Sadie glared at each other. Stanley was an absent bystander, his thoughts elsewhere. These departures had been happening since last Friday, when Joe Schwartz kissed him hard, led him upstairs, sat beside him on the bed, kicked off his Converse trainers, flicked the hair out of his eyes and said you’re wonderful, Stan, I really think you’re wonderful.

Canadian Joe. An Adonis. He was a magician too—he had turned down the bickering voices of Arthur and his mother so that Stanley could barely hear them. Something about a filthy dog. Something about his brother having a problem.

“I’m not impressed with you right now,” said Sadie.

“Oh really,” said Arthur.

“You talk to me like I’m a piece of shit. What’s your problem?”

“I don’t have a problem.”

“Just go and make me a coffee, Stan can help me finish. Stan, are you with us?”

Arthur marched through the kitchen in muddy boots, tapping on his iPhone.

Arthur Swoon @artswoon Mum drowning new dog in garden call RSPCA

Mark Williams @markwills249 @artswoon Really? Not the LOVELY Sadie? Don’t believe you

Arthur Swoon @artswoon @markwills249 Enough SICKO BOY thats my mother! My dad wearing hoodie not cool at his age

Mark Williams @markwills249 @artswoon Maybe he’s in midlife crisis? One word for you: MILF

When the twins were born, Ralph was still an undergraduate. He was twenty years old, passive and unworldly. He hadn’t wanted to call his sons Arthur and Stanley. He preferred Mark, Michael or Christopher, but he would never have risked arguing with Sadie about such crucial matters. They were fine, they were happy, he could lose her at any moment. This was the wordless core of their relationship, known and unknown. Sixteen years later they argued all the time and the sight of her Mini pulling into the driveway, its back seat covered with newspapers and unopened poetry anthologies, had begun to make him queasy.

Should your own wife make you feel queasy? Perhaps at the beginning, with the anticipatory fizzing, the urgent desire. But after sixteen years? What would she say if she knew?

“You make me feel queasy, dear.”

“You make me feel queasy too.”

“What now? A dry biscuit, a cracker, Alka-Seltzer?”

He took a digestive biscuit from the packet and put the kettle on. He listened to Sadie telling Stanley about an exhibition she wanted him to see—maybe they could go this afternoon, she said. There was a pause before the inevitable rejection: I’m sorry, Mum, but no can do.

“Why not?”

“I’m taking someone to the cinema this afternoon.”

“Can’t you go to the cinema another time?”

“Maybe you could see the exhibition with Kristin.”

“I don’t want to see it with Kristin, I want to take you.”

“But Kristin’s into art.”

“Will you shut up about Kristin?”

Kristin Hart. The boys’ godmother. She and her partner Carol were the paragons of contentment, which made them mesmerizing and annoying, even more so since Sadie found herself preoccupied with thoughts of Kristin in bed, Kristin in the shower, Kristin doing stretches before her morning run. Discombobulating, that’s what it was—the sexualization of an old friend. Really quite distracting.

Ralph closed his eyes.

He saw flickering lights, blocks of colour.

Yellow, black, reddish brown.

The talking had stopped. There was a moment of silence.

Yes, silence.

He exhaled into it, feeling his shoulders drop.

He noticed his fingers, the way they had curled into fists.

“I’m in such a foul mood,” said Sadie, marching into the kitchen with a cocker spaniel attached to her leg. “I need a coffee.”

“I’ll make it.”

“This bloody dog’s driving me insane. You can take him out this afternoon.”

“I don’t think so.”

“Why not? I need to get the food and drink for tomorrow. It’ll take me ages.”

His birthday party—something else he hadn’t wanted. But it wasn’t really for him. Sadie liked to surround herself with as many people as possible on a regular basis, otherwise his continued presence came as a shock.

“What do you know about Stan’s girlfriend?” she said, finishing her coffee while the spaniel licked her face.

“Are you sure he has a girlfriend?”

“I hope she’s not dull, like that girl he brought to the barbecue last month.”

“I thought she was perfectly nice.”

“He can do better than perfectly nice. She had no ambition.”

“Sadie, she’s a teenager.”

“When I asked where she wanted to be in five years’ time, do you know what she said?”

Ralph stood up, trying to decide whether to wash the dishes or go upstairs. “What?” he said, running the hot tap.

“In a swimming pool.”

“Maybe she loves swimming.”

“In five years’ time she wants to be in a fucking swimming pool? She could be in one now, Ralph. What kind of ambition is that? It’s like saying you want to end up on a toilet.”

“Sadie—”

“And do you know what else? She said her favourite restaurant was Frankie & Benny’s.”

His wife was oblivious to her own snobbery. Ralph blamed this on her parents, a lecturer and a mathematician who discussed current affairs, played the banjo and made home-made pesto, all at the same time. They were brilliant, quick, sarcastic. They lived in France and never visited. No child could ever emerge from their narcissism without hating herself, and Sadie had converted her self-loathing into something more tolerable: snobbery.

Ralph’s mother had been a housewife. His father worked for an upholsterer. It was no worse than Sadie’s background, it was just different, but try telling her that.

“Whatever,” he said.

“You sound like Arthur. Is that his hoodie you’re wearing?”

“Of course not. I don’t go around wearing our sons’ clothes. I bought this last year for running, don’t you remember?”

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen you run,” she said, head down, fiddling with her phone.

Ralph went upstairs, leaving a bowl of washing-up water that was supposed to smell of lavender and lemon, but actually smelt like the passageway between Asda and the car park.

Sadie Swoon @SadieLPeterson Off to MK’s this pm for the works: colour, cut, massage. Spirits need lifting!

Kristin Hart @craftyKH @SadieLPeterson Coffee afterwards at Monkey Business? We need to talk

Mark Williams @markwills249 @SadieLPeterson You’re gorgeous as you are #IfonlyIwere10yearsolder

Sadie Swoon @SadieLPeterson @craftyKH Coffee sounds great, meet you at 5pm?

Upstairs, Ralph was confused.

“Well blow me, I’ve forgotten why I came up here,” he said to no one.

Blow me. He almost Googled this phrase once, to discover its origins, but decided against it when he imagined the kind of sites that might pop up. He tried not to utter these words, especially when working with female clients, but saying blow me was something he had inherited from his father, along with narrow shoulders and a pert little bottom. Frank Swoon had been famous for his buttocks. Women wolf-whistled as he walked down the street. “Oh you do make me swoon, Mr Swoon. Just look at those little cheeks.” It was the kind of comment a man would have been slapped for.

Ralph’s confusion ran deeper than trying to recall why he had come upstairs.

In fact, it was chronic.

He was perpetually bewildered. He knew less about his own desires these days than his clients knew about theirs. Compared to him they were models of sanity, able to sit in front of him once a week and articulate their emotions with astounding clarity. Sometimes he wanted to tell them. He wanted to say hey, do you know how astounding this is, the way you know what you want? You may have a catalogue of neuroses, you may be anxious and depressed, but you actually know what you want.

Sadie had her own theory about his confusion. She was convinced that he hadn’t been the same since Easter, when he walked into a giant garden gnome in B&Q. Who puts an enormous gnome right at the end of an aisle? Ralph had complained to the manager, calling it a MAJOR SAFETY ISSUE. When the manager laughed, trying to hide his amusement inside an unconvincing coughing fit, Ralph threatened to call the police. Yes, he was overreacting. Yes, he should have been looking where he was going. But sometimes a gnome is not a gnome: it is a giant symbol of everything that’s wrong with your life.

Seconds before he headbutted the gnome, he was pretending to admire a vase of plastic daffodils. Insisting that they buy six bunches, Sadie was tweeting about how authentic they looked, how satisfying it was to have flowers that never died, and why hadn’t she thought of this before? Other people, miles away, were responding to her tweet. She was reading out their comments. Ralph stormed off down the aisle, unable to tolerate the peculiar hoo-ha evoked by the plastic daffodils, and he spotted Julie Parsley. Julie Parsley? And that was when he collided with the giant garden gnome.

Sadie held up her phone, took a picture of him rubbing his head, sprinted into the customer toilets.

What was Julie doing here in his local B&Q? Hadn’t she moved away? He remembered her singing ‘Move Over Darling’ on stage at the King’s Head; remembered her singing Ralph you’re so lovely, you really are lovely, to a melody she made up on the spot.

Her hair was short and wavy now, like that French actor—what was her name? Audrey Tautou. Yes, that’s the one. Ralph’s memory was still intact, despite the bump on his head, but Julie Parsley was nowhere to be seen. Her absence made him furious, even though she had been absent for much longer than the past few minutes. It made him shout. It made him complain about HEALTH and SAFETY and the BLOODY STUPIDITY of making a gnome that was as SOLID as a FUCKING WALL.

Ralph’s confusion had nothing to do with that day in B&Q.

It had nothing to do with Julie Parsley, his first love, aged fifteen.

And it had nothing to do with garden gnomes.

3

BUTTONS AND BUTTONS, MOON-HIGH

When the headmaster set eyes on Frances Delaney, sweeping the floor of the school corridor wearing nothing but a pair of trainer socks, he stood perfectly still and watched. He had never seen anything as strange and beautiful. His face was usually grey but not today. She had coloured him in. All around her, children were being children: wild, callous and despicable. They were like beetles, creeping bugs with hard shells. They said what they liked with vile spontaneity. Apart from little Miriam Delaney, of course. She was quiet, well behaved, positively ghostly. And with a mother like this, who could expect anything less?

He walked towards her, flicked the children away, took off his jacket and wrapped it around her shoulders. She was warm, because her sweeping had been furious. When Frances cleaned, the bugs knew she was coming. Beside her feet the floor was shining.

“I think you should come with me,” the headmaster said, leading Frances along the corridors to his office. Her eyes were glazed, there were no words in her mouth. He pulled his National Trust blanket from the cupboard, blue and white and scratchy, smelling of tobacco. “Here,” he said, offering it to Frances. “We’ll find your clothes and then I’ll drive you home. Does that sound like a good plan, Mrs Delaney?” His palms were wet, his breathing was quick. “Were you actually wearing any clothes when you left the house?”

That afternoon, at the end of the school day, Miriam walked home by herself as usual. She worried about the safety of cats outside all day long, worried about what kind of concoction she would be given for tea, worried that other children would be meaner than ever and what that meanness might look like. Today had been the loudest day. No wonder you’re a fucking weirdo, Delaney. Your mother’s a nutter. Get your kit off, show us what you got, you both fucking nudists, is that what you are?

She opened the front door of 7 Beckford Gardens, walked along the hallway to the kitchen.

They were on the table.

On it.

Just like her boiled egg and soldiers this morning.

Just like her colouring books and felt-tip pens.

No amount of disinfectant would ever make this right.

She thought about that as she stood in the doorway.

Thought about cleaning products, wondered how many bottles there were in the world.

And eventually they stopped grunting.

He stumbled backwards and zipped up his trousers.

She was still wearing her trainer socks.

And her black bowler hat.

“Well hello, Miriam,” the headmaster said. “Did you have a good day at school?”

*

Miriam has vacuumed the front room and the hallway and it’s time for a celebratory cup of tea. She dashes past the glass panels in the kitchen door and catches sight of her own body. She pauses, her eyes widen. Is that me? A woman in knickers and novelty slippers, who has just sucked up dust using a hoover called Henry as though there is nothing in the world to be afraid of.

She remembers something Fenella once said: “The past is the past.” Stating the obvious makes Fenella happy. “It is what it is,” she often says.

Miriam tried stating the obvious for a while, to see if it improved her well-being, but it only made her feel crazier than usual:

“This is a packet of Weetabix.”

“The future is the future.”

“Death means never seeing someone again.”

“This is a pint of milk.”

“The present is the present.”

“I’ve never spoken in more than a whisper.”

“What I mean,” Fenella explained, “is no one can set foot in this house without your permission. Your mother’s gone. The past is the past. Catch my drift?”

None of those statements seemed connected, but Miriam caught her drift. It can take a long time to believe that something is over. That’s what Fenella had been trying to say. But it is. What’s done is done.

She sits at the kitchen table and sips her tea. For once, just for a few minutes, there is no history on her back. There is no history crawling over her skin and poking into her mouth. History will return as quickly as you can whisper Frances Delaney, but these small moments, these victories, have to be marked. They are the flags of progress. Signposts to normality.

The letterbox rattles.

Who gets post at eleven o’clock at night?

It’s another postcard, the sixth one Miriam has received over the past few weeks. On the front, a photograph of an old-fashioned bike, leaning against the wall of a French cafe. On the back, written in green ink:

YOU COULD SIT AND READ A BOOK IN A CAFE, MIRIAM. YOU COULD CYCLE THROUGH THE STREETS WITH THE WIND IN YOUR HAIR

Like the others, this postcard is anonymous. She sticks it on the noticeboard beside the rest and looks down at her slippers. These slippers are not sexy, she thinks. But have I ever been sexy? She flexes her toes, making the two West Highland terriers nod and say of course you have, Miriam, of course you have.

Sex. Now that should have appeared on the list of things she is afraid of. It’s not sex itself that’s the issue, it’s the fact that it has to involve another person. She told Fenella this last week.

“What on earth do you mean?” Fenella said.

“Well, it’s not the act of sex,” Miriam said, wishing she hadn’t phoned. Fenella had just got home from Zumba and was disarmingly energized.

“Right.”

“It’s having to be with someone.”

“So you’d be fine with a blow-up doll, is that what you’re saying?”

“That is certainly not what I’m saying.”

Fenella laughed. She opened a packet of Quavers and settled into an armchair.

“What’s that noise?”

“I’m eating crisps.”

“Doesn’t that defeat the object of Zumba?”

“How could it?”

“I don’t know.”

“Exactly. So back to sex. It’s never too late to get started,” Fenella said, but it was all right for her. She started when she was sixteen in a caravan in Newquay with a boy who liked to be called Lucy. It was the Price family’s summer holiday. Her parents were playing bingo in the town hall. Her brother was in the pub with a girl who liked to be called Pattie. It was raining, they were playing cards and Lucy (otherwise known as Martin Henley) said let’s do it and they did.

“Just like that?” Miriam said.

“Just like that,” Fenella said. “It was bloody awful but I felt fantastic afterwards.”

“You’re not exactly selling it.”

“I don’t need to sell it. It’s everywhere. It sells itself.”

“Why did he like to be called Lucy?”

“Why not?”

It was a good question. Fenella was full of those—questions that probed your assumptions and required no answers.

“At least I could do the pillow talk,” Miriam said, which made both of them quiet and sad.

“One day,” Fenella said.

“What if it never happens?”

“Whispering’s not a crime.”

So why does she feel like a criminal?

Miriam runs upstairs and puts on her pyjamas. That’s enough cleaning for one night—no need to overdo it. She sets a track playing on her CD player: ‘Wicked Game’ by Chris Isaak. It’s a song about the wickedness of love and a woman who has made someone think about her all the time. Miriam understands thatkind of wicked—the taking over of mind and body—but she knows nothing about love. She has never experienced the kind of thing Chris Isaak is singing about, never fallen in love or had anyone fall in love with her. In fact, she is not even sure that she has met someone who is in love. Do they look different to other people? Are they easy to spot? Her mother always said that love was for people with dirty houses.

She looks in the mirror and knows what she is. She is buttoned-up. Buttons and buttons, moon-high. Imagine a night sky studded with buttons. Imagine Miriam’s buttoned-upness living in a jar—the jar would be full of navy-blue ink, the kind you might use to write a letter to your grandmother, a letter on Basildon Bond writing paper, watermarked blue, saying you were sorry, so sorry, for everything.

Dear Granny,

I am so sorry Mummy does not let me visit. She says you are too normal to be good for me. I have looked for normal in the dictionary at school and copied out what it means in case you cant remember.

conforming, usual, typical, expected, free from physical or mental disorders

I think normal is nice can we meet in secret to be normal soon? Please write back and tell me if you think this would be nice.

Lots of love,

Miss Miriam Delaney

Chris Isaak has a soul-stirring voice. Some people can do that—they can reach into your soul and stir things around. He is truly soulful. My voice is full of your soul—the parts I took when I stirred you around. His crooning makes Miriam wonder what it would be like to look at her bed and see someone lying under the duvet. Someone else. What a wicked song! It’s the soundtrack to a future that feels terrifying, exciting, possible, impossible. Her toes tingle inside her fluffy slippers.

Dear Granny,

I have still not heard from you and it has been two long days. Please reply immediately thankyou. I need to know if you would like to be normal and have a secret life with me.

Love Miriam xxx

Dear Mrs Betty Hopkins,

It has now been three days and I hope you are not ill. You are my hero Granny. I will keep this letter short in case you are very very busy. I love you.

M xxxxXxxxx

Dearest Miriam,

How lovely to hear from you! I daren’t call, because your mother isn’t well and she says that my phone calls upset her. Don’t fret about things, Miriam. Your mother is trying some new medication and all will be well soon. When she recovers I’ll take you to the park, or into town, and we’ll revel in normality. Look up “revel” in your school dictionary, Miriam—I think you’ll like it. It means to have lively and noisy fun. Your mother doesn’t like noise, and this must be hard for you, but please remember she is poorly and it isn’t your fault. Keep in touch, and if anything nasty happens just run out of the house and get in a taxi and I will pay the bill when you get here, all right? In the meantime, I’ve enclosed some new buttons for your collection. I bought them while I was on holiday in Scarborough. There are lots of buttons up north.

With love, as always,

Granny

Miriam sighs. She still misses her grandmother. The sight of those envelopes, her own name and address in that small, neat handwriting, made her feel like a real girl in a real house—a person of fixed abode, properly and officially there. But just as important was what happened in the act of writing. When Miriam composed her sentences, the voice inside her head sounded like any other girl. There was an unbroken stranger inside Miriam Delaney—the same age but louder, the same height but taller.

That stranger is now a woman and she is still buried deep. She is a doll inside a doll. Pull a string on the outer doll and nothing happens. Pull a string on the inner doll and she speaks. Trouble is, no one can hear the inner doll. No one knows she’s there.

How long is a piece of string?

People just string me along.

What’s done is not done.

She blinks her thoughts away, walks across her bedroom to the window. What’s happening out there in other people’s houses? She imagines a parallel world, another Miriam, then another. The multiplication of a person. All the possible versions of Miriam Delaney. Longer hair, short hair, dressed all in black, multicoloured, tomboy, girlish, a woman with a powerful voice, a leader, a follower, an artist, a midwife, a waitress, a driver, a baker, a scientist, a policewoman. No, not a policewoman—then she would have to arrest herself for the thing that happened. A woman with a boyfriend, a girlfriend, a son, a daughter, a cat, a dog. A woman who receives invitations and says yes please, thank you so much for inviting me. A woman who receives compliments and says thank you, how kind of you to say so, instead of blushing and squirming and hating the person for taking the mickey.

Which version would she be now if Frances Delaney had handed her to her father and walked away? A brand-new baby, a brand-new life. He lived in this house for almost a year after she was born, then he went into the garden and never came back. Ruptured brain aneurysm. He was hanging out the washing—Miriam’s Babygro. It was yellow, with a brown monkey on the front. It had to be washed again because it fell in the mud. So many details but none of them matter.

He was here and he was gone.

It was what it was.

It is what it is.

She closes her eyes, watches him smile as he jiggles her up and down, hears him sing a lullaby as he puts her to bed.

Made-up memories of a dad.

Stupid.

4

WHAT A LEAKAGE, WHAT A SPILL

Ralph was in his consulting room in the centre of town, drinking coffee by the window. He watched a woman in the street below, clacking along in flip-flops, sipping cider from a can. Then a young man in a pinstriped suit, a woman and a child, three conspiratorial teenagers nudging each other.

It was Saturday morning. 9.30 a.m. His birthday.

Some people love birthdays. Not Ralph. He has always hated them, now more than ever. The spotlight, the pretence. That’s why he was at work, standing by the window, watching a man selling the Big Issue, a woman jogging in Lycra.

He thought about his parents, remembered all the birthday parties they threw for him, the house full of balloons and children and pass-the-parcel. “Never waste an opportunity to celebrate,” his mother said, her hands on his face. “We know you’d rather sit on your own, but relationships are everything, Ralph.”

He turned around and looked at the room. A desk and a wooden chair. A white fireplace. Two leather armchairs facing each other. This was where it happened—the conversation that formed the centrepiece of his working life.

Before becoming a psychotherapist, Ralph worked as a gardener. He was happy doing odd jobs for odd people who hovered in the background while he worked, chatting about the flowers and the weather and then, charmed by his softness and discretion, about their innermost thoughts. Sadie didn’t like being married to a gardener. She didn’t like him working for odd people who hovered in their gardens. She said it was beneath him, his face would age quickly in the sun, and soil would remain lodged in his fingernails.

“Why can’t you set up a proper business and work for bigger clients? You could get a decent van with a company logo on the side. A tree would be nice. A grey van with a big white tree. Oh yes, I can see you driving through town in one of those.”

“What a waste of money. I’m fine as I am.”

“You spend all day talking.”

“Yes, but I get paid for it, don’t I? And I get plenty of work from personal recommendations. I don’t need a bloody logo.”

After years of weeding, digging and planting, of discussing dreams and anxieties and the knottiness of self-awareness, Ralph realized that he was, in fact, doing more talking than gardening. Egged on by one of his clients, a psychoanalyst named John Potter, he picked up a leaflet about psychotherapy courses. The training sounded expensive and intrusive, but John Potter assured him that all the best things in life were expensive and intrusive. (This led John to recall an energetic weekend in Amsterdam, which cost him two thousand pounds and triggered an episode of angina, but it was worth it.) And besides, he could study one day a week and continue with his gardening. What did he have to lose, apart from his savings?

Sadie was keen. “I’d like to say my husband is a psychotherapist,” she said.

“What does that even mean?” he said.

Seven years later, he emerged from his training with a master’s degree and a stomach ulcer. He rented a consulting room in town and gave up his gardening. He spent his weekdays in that room, listening to people’s stories, searching for patterns in their thoughts, feelings and behaviour, until a few months ago, when he had a small epiphany with a client named Jilly Perkins.

“And so I’ve realized,” said Jilly, flicking her highlighted hair, “that I like to be free. I just need it. I like to take on short commitments, because that way the end of the tunnel is always in sight. It’s nothing to do with fear of commitment. I just need to be able to see the end of the tunnel.” She leant forward and looked him in the eye. “It’s who I am,” she said. It sounded like a threat.

The end of the tunnel, he thought. That’s where the light lives. That’s where it’s been hiding. Tunnel vision, darkness and darkness, tunnelling through pockets of time.

Jilly Perkins was a genius. Ralph wanted to tell her this, but she hated compliments. They filled her with wind and suspicion. This was the issue they planned to work on next, and in the meantime she had a handbag jammed full of Wind-eze capsules. “I love Wind-eze,” she said. “I think of them as mints with benefits.”

Ralph stifled his compliment by slapping his leg. Jilly laughed. She had never seen her therapist look so happy. In fact, had she ever seen him look happy? Does a person have to look happy to be happy? And what does happy mean anyway? She sighed. The questions had dispersed her happiness like small hammers hitting a row of pills. A wave of melancholy carried another insight: Happiness is easily dispersed, Jilly Perkins. Just you remember that. Don’t question everything. Don’t forget the small hammers.

That evening, inspired by Jilly’s tunnels, Ralph wrote new text for his practice leaflet:

RALPH SWOON MA HIP, UKCP REGISTERED

Specializing in short-term psychotherapy

(No long-term work undertaken)

Moving to short-term work was a step down a tunnel towards a light. He was on his way out of a profession, edging backwards, coming undone. His clients weren’t to blame. They were brave and open and he admired their attempts to make sense of themselves. He simply wished they were plants.

Ralph sat at his desk. The building was quiet. No one else was here. He looked at the photo above his desk: a bluebell wood in Guernsey.

His mobile rang. It was Sadie.

“Where are you?”

“I’m at work.”

“Really?”

“I had some paperwork to do.”

“Really?”

“Why do you keep saying really?”

“It’s your birthday.”

“I went for a run, so I thought I’d call in and finish a few things off.”

“A run?”

“Yes.”

“What things?”

“Admin.”

“I woke up and you weren’t here.”

“Sorry. I should have left a note.”

“No, you should have stayed. I bought croissants.”

“I’ll be home soon. An hour at the most.”

“We need to get the house ready for the party.”