Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

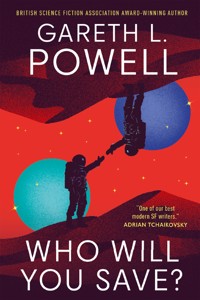

Action-packed and thought-provoking stories ranging across the dead sands of Mars to the backstreets of Buenos Aires, from the febrile mind of BSFA Award-winning author Gareth L. Powell. 32 stories featuring the author's most celebrated tales alongside all new material, a thrilling experience for established fans and new readers alike. Ranging from the dead sands of Mars to the half-flooded remnants of Amsterdam, from the seedy backstreets of Buenos Aires to the gravity well of a singularity, these action-packed tales explore mind-bending ideas through the eyes of unforgettable and all-too-human characters. As their lives implode around them, will they use the moment to save their own skins, or to find a way to make up for past misdeeds? Who will they save? Who would you save? This entertaining and thought-provoking collection features work drawn from Powell's twenty-year career as a writer, his best-loved stories, and previously unpublished material revisiting the expansive settings of his acclaimed science fiction sagas.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 533

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Sunsets and Hamburgers

Ride the Blue Horse

Waiting for God Knows

An Examination of the Trolley Problem Using a Sentient Warship and a Rotating Black Hole

From the Table of My Memory I’ll Wipe Away All Trivial Fond Records

Railroad Angel

Fallout

The New Ships

Hot Rain

Gonzo Laptop

Flotsam

The Last Reef

The Redoubt

Distant Galaxies Colliding

Red Lights and Rain

Entropic Angel

Pod Dreams of Tuckertown

The Bigger the Star, The Faster It Burns

No Human Eye

Eleven Minutes

The Wind Through the Tall Grass

Morning Star

Six Lights Off Green Scar

Line Against the Darkness

Falling Apart

Dusk of the Dead

Ack-Ack Macaque

A Necklace of Ivy

Silver Bullet

Apprehension Sands

Movies and Bottled Beer

What Would Nicolas Cage Do?

About the Author

GARETH L.

POWELL

WHO WILLYOU SAVE?

Also by Gareth L. Powelland available from Titan Books

Jitterbug (coming Feb 2026)

Future’s Edge

Stars and Bones

Descendant Machine

Embers of War

Fleet of Knives

Light of Impossible Stars

GARETH L.

POWELL

WHO WILLYOU SAVE?

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Who Will You Save?

Print edition ISBN: 9781803368658

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803368665

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2025 Gareth L. Powell

‘An Examination of the Trolley Problem using a Sentient Warship and a Rotating Black Hole’ appeared in

Worlds of IF

, 2025.‘A Necklace of Ivy’ appeared in

Cambrensis: Short Story Wales

, 1992.‘Ack-Ack Macaque’ appeared in

Interzone

, 2006.‘Distant Galaxies Colliding’ appeared in

Quantum Muse

, 2004.‘Eleven Minutes’ appeared in

Interzone

, 2011.‘Entropic Angel’ appeared in

Dark Spires

, edited by Colin Harvey, 2010.‘Falling Apart’ appeared in

The Last Reef and Other Stories

, 2004.‘Fallout’ appeared in

Conflicts

, edited by Ian Whates, 2010.‘Flotsam’ appeared in

The Last Reef and Other Stories

, 2008.‘Gonzo Laptop’ appeared in

Hub

, 2010.‘Hot Rain’ appeared in

The Last Reef and Other Stories

, 2008.

‘Morning Star’ appeared as ‘Catch a Burning Star’ in

Aphelion

, 2004.‘Pod Dreams of Tuckertown’ appeared in

Byzarium

, 2006.‘Railroad Angel’ appeared in

Interzone

, 2012.‘Red Lights, and Rain’ appeared in

Solaris Rising 3

, edited by Ian Whates, 2014.‘Ride the Blue Horse’ appeared on

Medium.com

, 2015.‘Six Lights off Green Scar’ appeared in

Aphelion

, 2005.‘Sunsets and Hamburgers’ appeared in

Byzarium

, 2006.‘The Bigger the Star’ appeared in

2020 Visions

, edited by Rick Novy, 2010.‘The Last Reef’ appeared in

Interzone

, 2005.‘The New Ships’ appeared in

Further Conflicts

, edited by Ian Whates, 2011.‘The Redoubt’ appeared in

Aphelion

, 2007.‘What Would Nicolas Cage Do?’ appeared in

Future Bristol

, edited by Colin Harvey, 2009.

Gareth L. Powell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, [email protected], +3375690241

For Dianne, Edith, Rose, and Robin

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The stories in this volume may differ slightly from earlier publications, due to corrections or minor revisions. As such, this collection should be considered to contain the definitive versions of these stories.

SUNSETS AND HAMBURGERS

1.

My first thought is that I don’t remember dying. They tell me nobody does. It’s like trying to catch the exact moment you fall asleep; when you wake, it’s gone. You may remember feeling tired, you may even remember starting to fall asleep; you just don’t remember the transition, the actual moment when you passed from one state to the other.

And then they resurrect you.

One minute you’re nowhere, nothing. The next you wake up coughing and thrashing in a tank of blue gel.

2.

My stomach’s full of gas and my bowels full of water. My brain feels like melted polystyrene. Every thought hurts and every breath is an effort.

The robot doctors try to reassure me. Everything’s going to be okay, they say.

And then, just when I’m beginning to wonder if the worst is over, they take me out and show me the sky.

What’s left of it.

3.

The doctors tell me that I’ve been dead for billions of years. They give me pamphlets to read, films to watch.

Billions of years!

I’m struggling to imagine it. Every time I get close, I get breathless and my hands start to shake.

4.

I have a few confused memories: faces, names of places, that sort of thing. I have an image of a sash window on a grey and rainy autumn afternoon, and bass-heavy ska playing somewhere off down the dull street. And after that, there’s nothing. I fall to my knees and begin to weep.

The doctors comfort me. They’re pleased with my progress.

5.

There’s something dreadfully wrong with the sky. They try to explain it but I have trouble understanding.

When I was alive, I worked for a financial software company. I worked in their marketing department, writing letters and making calls. In my spare time, I liked sunsets and hamburgers, movies and bottled beer.

It’s something to do with black holes, they say, pointing at the blank sky.

Like everyone else, I skimmed through A Brief History of Time once or twice, but I’ve got to admit, I’m struggling with this one.

6.

Today, the robot doctors introduce me to Marla. She has feathers in her hair, and her clothes are made of vinyl.

They show us to our new home. It’s small but comfortable; reassuring, in a simple, everyday kind of way. There’s a kettle and a toaster, a stereo and a CD collection. There’s even a TV.

“You can stay here as long as you need to,” they say.

The porch looks out over a sandy beach. Wild palms sway in the offshore breeze.

7.

We’ve been here a couple of weeks now. The pamphlets are starting to make sense.

The sky’s dark because the galaxies have flown too far apart and the stars have exhausted themselves. In order to survive, the remaining people huddle close to the embers of the leftover black holes.

8.

We’re sitting on the porch watching breakers crash and slither. It’s late in the evening and there’s music drifting out from the kitchen.

Marla’s upset.

The doctors have given us a new pamphlet.

Throughout history, it says, love has served a serious evolutionary purpose. It compels us to look after those around us, and to allow them to look after us. This is the root of community, and the groups that survived and prospered were those with the most love.

It goes on to explain how they matched our personalities, made sure our genetic traits complemented each other. Apparently Marla and I are over ninety-eight per cent compatible.

They want us to have kids.

9.

When I was a student, I used to like to spend the afternoon in a city-centre bar reading the newspaper, doing the crossword and watching the world go by. It was like meditation, the mind roaming free: the rattle of coins in the fruit machine, the hum of the pumps and refrigerators, the low murmurs of the bar staff.

And when I finally left the bar, just around the time most people were finishing work for the day, I’d stumble out with my senses heightened. Suddenly, everything seemed significant. I’d want to write poetry or paint something, just to capture this perfect feeling. But I never could. My efforts never stood up to the critical light of the following day.

Sometimes now at night, when I wake up beside Marla, I have a similar feeling: everything feels sharp and unreal and meaningful, as if I’m waking up in a movie and everything’s somehow symbolic.

If I keep my eyes shut it passes, after a while.

10.

Babies cry out in the night. We nudge each other awake. There’s a noise outside. Marla sees to the children while I go out to investigate.

Those damn trilobites have been going through the bins again. They skitter around the beach in the dark, some of them as big as my foot.

Overhead, there’s a fine selection of moons.

11.

We’ve been here for a year now. Every morning, there’s a cardboard box of food waiting for us on the kitchen counter. Some days it’s mostly fruit, other days it’s fresh bread and cold meat. Today, it’s a jar of instant coffee and a pack of Silk Cut.

When I unscrew the lid on the jar and tear the cellophane from the pack, the sticky familiar smells hit me like an adrenalin rush.

The coffee smells like heaven. Before I’ve time to think, I’ve made myself a steaming cup. And damn, it does taste good. It’s like visiting a town where you used to live or finding a fiver in the pocket of a pair of jeans you haven’t worn for a while. The cup feels natural in my hand, comforting.

I drink about a quarter of it before I have a strange feeling in my stomach.

I leave the cigarettes where they are, but I can feel them watching me.

12.

Every now and then I have a doubt, like a shadow moving in the corner of my eye.

Have we been seduced by the sand and palms into believing we’re living a perfect life, here on the beach, with the kids?

They’re growing up strong and clever. They have their mother’s looks and their father’s restlessness.

I can’t help feeling that we were pushed into having them, like we were selected to breed the same way you’d select a couple of pedigree cats.

Is that why they brought us back? To have kids?

Has something so catastrophic happened to humanity that it needs to resurrect untainted individuals from the past to repopulate the Earth? Are our descendants all shooting blanks?

13.

One day it hits me.

When they brought us back, they must’ve made alterations to our minds. I don’t know how or why, but I think they tailored us when they resurrected us.

I look at Marla and know the urge to make babies with her is stronger than anything I felt in my former life. Back then, I used to panic if you put me in the same room as a baby. Now, I can’t seem to get enough of them.

How can I talk about any of this with Marla? She’s already three months gone with our fifth.

“You’ll stop loving me if I get any fatter,” she says.

14.

The doctors have disappeared. They don’t answer our calls. The hospital is deserted, empty. It’s almost as if they’ve fulfilled their task and taken their leave.

Marla doesn’t like it. It gives her the creeps to be suddenly alone.

15.

They left us a final pamphlet, pinned to the door. It doesn’t make for happy reading.

It tells us how vicious wars erupted as the final stars began to gutter. It tells us that huge reserves of life and power were burned as various factions competed for survival. Stealth ships slipped like sharks through the woven fabric of the universe. Titanic energies were squandered in futile attacks.

And now here we are, in our cabin by the sea. A little bubble world, a few miles in diameter. Fragile and lost in the encroaching darkness.

16.

We’re close to the end of everything. Beyond our snow shaker bubble of greenery and life, the universe is a sterile wasteland. There may be other survivors in other galaxies, but they’re irretrievably lost to us now, pulled away into the expanding darkness so that not even their light can reach us.

Eventually, the black hole that provides the energy for our heat and light will evaporate. We’ll have a few years left after that, but they won’t be quality time.

We’ll go down with the dying universe. We’ll see the final wisps of the Milky Way torn asunder; we’ll feel the ground begin to rip beneath our feet, feel our bodies begin to break apart.

And what happens after that? On the face of it, it looks like time ends.

I have a hunch, a feeling, that the doctors brought us back to do more than simply witness the death of creation.

But if that’s all that they wanted us to do, why did they encourage us to have so many kids?

17.

In my former life, I used to read science fiction now and then. One evening, in bed, I try to explain the attraction of it to Marla. Beyond the sand, the sea stirs restlessly.

I want to tell her about the joy of imagining strange new worlds filled with bizarre and dangerous creatures, of watching mighty armadas blow hell out of each other, but she flicks her hair dismissively and I know I’m not getting through.

Through the window, two of the brighter moons linger on the horizon, one gold and the other amber. Their reflections shimmer on the dark water.

I tell her that my grandfather dreamt of going to sea, of finding fortune and glory in mysterious far-off lands. It wasn’t my fault that by the time I hit my teens, the few remaining earthly frontiers were already full of holiday show camera crews and Australian gap year students. There were no mysterious lands left, save those that lay in the books I read.

“I guess what I’m trying to say is that all my dreams seem to be coming true,” I say. I want her to understand that before I came here, the local library was my only frontier.

She looks at me for a long time, and I honestly can’t read her expression. Then she turns over and wraps the sheet around her shoulders.

My legs are left sticking out. I get goose bumps.

18.

Marla says I think too much. She thinks I’ll poison the kids by telling them that there’s no point to their dreams and ambitions, by telling them that the universe is ending.

But deep down, I know there’s hope.

19.

I’m sloshing through the surf, wondering why the doctors have gone to so much trouble to replicate coffee, cigarettes and a tropical paradise, why they resurrected a breeding pair of homo sapiens.

And then the three juggernauts appear in the sky.

They must each be half a light year in length. As we watch over the next few hours, the effect of their mass scrambles the remains of our solar system, but not before their shuttles swoop down and snatch up our little bubble biosphere from the ashes.

20.

It’s still half dark when I rise at noon and take my coffee out onto the porch. The kids are playing in the gloomy sand. It feels like the high end of summer and the air’s stale and used. A vast vault arches overhead. Lights in its roof look like brightly burning stars. Around us, on the cavern’s floor, we can see the glow of other collected bubbles; they shine green and blue in the gloom. I wonder who they contain, and if we can reach them.

21.

This will be my last diary entry.

These giant ships seem to be arks, of a sort. I can’t tell you where they’re going, or what we’re going to do once they get there. I can’t even tell you why we’re here, alive, at the end of time.

All I can do is repeat the same conclusion that every man or woman has reached since the dawn of time: I don’t know why we’re here, or how long we’ve got, but we’re here.

And we’re going to survive.

RIDE THE BLUE HORSE

We were breaking into shipping containers the day we found the blue horse.

My friend Dan had convinced me we should give it a shot. The stacks were dangerous, but since we got the sack from the call centre we were desperate.

“I heard of a guy two towns over,” Dan said, rocking back and forth on his heels in the call centre parking lot, “who cracked a container of canned fruit. Peaches, cherries, and mandarins – stuff you just don’t see any more. It made him rich.”

“How rich?”

“Rich enough to leave town.”

We had to walk to the freight yard, and it took us the whole day. Heat shimmered off the empty road. The place had been abandoned since we were kids. With the big ships gone, it just hadn’t been economical to keep open. And once the port authority stopped dredging, it only took a couple of years for silt to choke the harbour. All that was left now were these rusting container stacks, and the wiry, little green fireworks of grass that had burst up through the shattered tarmac.

The perimeter fence had been smashed down in several places. “Are you sure there’s going to be anything left?” I said.

Dan gave me one of his looks. He was still wearing his call centre clothes, dark jeans with a white shirt and black tie, and his top button was undone.

“Look at the size of this place. It’s about a bazillion square kilometres. There are literally thousands of crates.” He stepped through the fence with the sprightly confidence of a door-to-door evangelist. “The ones at the edges may have been looted, but I’ll bet you there’s still plenty of good shit further in.”

“You’d better be right.”

“Of course I am.” He clapped his hands together and rubbed them briskly.

“Now come on, Spelman, let’s hustle.”

As it turned out, he was right. But we had to open six crates before we found her.

The first three were full of machine parts, electric kettles, and other junk that was either to heavy to carry or not worth the effort. The fourth was empty, and the fifth strewn with the discarded rags of a shipment of long-forgotten immigrants.

At that point, I was ready to give up for the night. The sun was going down and the sky was ripening towards the colour of a day-old bruise. Dan convinced me to continue.

“Just one more.” He slapped the side of the next container in line and the metal made a deep booming sound. “Come on,” he said, “I’ve got a great feeling about this one.”

Dan injured himself as we were prying off the lock. The crowbar slipped, and the end of it gashed his palm.

“Goddammit!”

“Are you okay?”

“Just peachy.” I watched him suck the wound. Thankfully, it didn’t seem deep. We both knew we didn’t have enough money to get him a tetanus shot.

With his hand still in his mouth, he kicked the door.

“Get this sucker open, Spelman.”

“Yes, sir.” I stooped to retrieve the fallen crowbar, and carefully popped the lock.

The door opened on rusty hinges.

“What have we got?”

I frowned into the gloom. “Some jerry cans and kit bags... and something wrapped in a tarpaulin. I think it might be a car.”

Dan pushed past me.

“Well, there’s no need to sound so disheartened.”

He crouched in front of the covered vehicle and pulled at the edge of its shroud. “Voilà!”

The cloth came away and he stood there like a conjuror awaiting the applause of the crowd. I looked at what he had uncovered.

“Pretty car.”

“Pretty?” He dropped the edge of the tarpaulin and walked around to the driver’s door. His fingertips brushed the blue bodywork. “You don’t even know what this is, do you, Spelman?”

“Nope.”

He shook his head sadly, as if disappointed in me.

“It’s a 1960s Ford Mustang with a V8 engine and four-speed manual gearbox.” Dan was quite the student of classic Americana. Plus, his dad had once owned a garage out near the interstate. He opened the door and slid behind the wheel. “And the keys are in the ignition.”

I walked over and kicked one of the jerry cans. The dull thump told me it was full. I unscrewed the lid.

“Petrol. And these bags are full of camping supplies and dehydrated ration packs.”

Dan was beside me in an instant.

“Put all of it in the trunk.”

I raised an eyebrow. “You think it’s worth something?”

“Are you kidding?”

He helped me load the car, and then we both climbed in.

“You know what this is?” He gave the steering wheel an affectionate pat. “It’s somebody’s cache. It’s their end-of-the-world back-up plan, only they never came back for it.” He laughed. “Just imagine for a moment, some wannabe Mad Max trapped in a departure lounge in Washington or Buenos Aires, knowing the planet’s going to hell but being unable to reach all the gear he’s so carefully squirrelled away.”

He pulled a pair of sunglasses from the glove box, and admired himself in the rear-view mirror.

“So,” I said, “how much do you think we can sell it for?”

He looked aghast. “Where’s your imagination, Spelman? This might be the last functional car in America. Do you know how far a blue horse like this could get us on a full tank of gas? At least two or three hundred miles. And then we’ve got the refills in the trunk.”

“And when they run out, then what?”

“And then we’ve got all this neat camping gear, and these rations. I’ll bet they’re super tasty. They’ll keep us going until we find someplace.” He put his hand on my shoulder. I could feel warm, sticky blood soaking through my t-shirt. “We can hit the road right now, and never come back to this ungrateful crap-hole.”

My skin prickled the way it did before a thunderstorm.

“Not... ever?”

“Nope.” He lit the headlights and we blinked against their sudden brilliance.

“One question.” I fastened my seatbelt. “Do you actually know how to drive?”

He turned the key in the ignition. The engine coughed twice, and then bellowed. The metal walls amplified the sound. I caught a whiff of carbon monoxide. Dan released the parking brake.

“No, I can’t say I do.” With his bloodied hand, he crunched the gearstick into first and eased up the clutch. We began to roll forwards. “But really, how hard can it be?”

WAITING FOR GOD KNOWS

AN EMBERS OF WAR STORY

The pack and I were at rest relative to the local frame of reference. The main body of the fleet were in action elsewhere, but for reasons best known to them, and them alone, the Conglomeration Navy’s top brass had decided to keep us in reserve.

“It’s an outrage,” Fenrir grumbled over our common channel.

If the rumours in the fleet were true, this could be a decisive strike against the Outward. Their generals were having a conference on a jungle planet, and if we could take them all out with one blow, the Archipelago War would be effectively over. All that would remain would be mopping-up.

“Patience,” Anubis advised. “They have a strategy. When we are needed, we will be called.”

“We could be there already.”

We were six Carnivore-class heavy cruisers. Our brains had been cultured from the cloned neural tissue of fallen soldiers, with a pinch of canine DNA thrown in to ensure ferocity and pack loyalty. We liked nothing more than wreaking havoc on the enemy – on any enemy – and yet here we were, in the shadow of an ice moon orbiting the ass-end of nowhere. I wasn’t the most impulsive among us, but I have to admit even I felt twitchy. I had been designed to fight, and I needed to fulfil my function. We all did. And knowing action was happening elsewhere and we weren’t part of it gave us all a serious case of FOMO.

“The war might be over by the time we get there,” Fenrir said.

“Nevertheless, we wait.”

“And what are we supposed to do while the most important battle of the whole conflict happens without us?”

Dear, sweet Coyote said, “How about charades?”

Everyone else ignored her. They treated her like the runt of the litter, just because she was younger than the rest of us.

I pinged her a sympathetic emoji, “Maybe now isn’t the right time?”

She sent me a smile emoji. “Thank you, TD, you’re always looking out for me.”

“Well, someone has to.”

I felt my brother Adalwolf stir beside me. “What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Nothing.”

We lapsed into radio silence once again. Our crews were at their posts. They wrote letters, wept soundlessly, talked loudly, murmured prayers – and did all the other things that humans tend to do on the eve of battle.

“The waiting,” more than one of them said, “is the worst.”

I’d heard the same sentiment a hundred times before, and it always filled me with pity. I understood how the anticipation of a coming conflict could play on the nerves – how you’d want it to just be over already – but that impatience was nothing compared to the shock and pain of losing a limb or having your lungs shot full of so much shrapnel that you drowned in your own blood.

Humans were so fragile.

“Maybe we should meet in person?” War Mutt said. “I’ll host.”

I heard Adalwolf sigh. “Very well, sister. But will you try to make the setting a little less ostentatious than your last effort?”

War Mutt sent a skull-and-crossbones emoji. “It was the fucking Louvre,” she said. “You philistine.”

* * *

This time, the virtual environment War Mutt created for us seemed a little more tailored to our collective tastes.

“What do you call this place?” Coyote asked. She’d chosen to manifest as a teenage girl in a baggy woollen jumper of indeterminate colour.

“It’s the Colosseum,” War Mutt replied. Her persona was that of a soldier, in a simple one-piece set of camouflage fatigues and a green baseball cap embossed with the Conglomeration Navy logo.

“And who are all those people?”

“They’re gladiators, dear.”

“They seem very excited.”

“They’re fighting,” I said. As usual, I’d elected to appear in the guise of the soldier whose stem cells had been harvested in order to culture my mind, but instead of a uniform, I wore a white shirt and black tie, and a long khaki trench coat.

Coyote looked at me. “Then why are they playing with those cats?”

Arterial blood sprayed the sand of the arena.

“Those are tigers, and they’re not playing.”

“Oh.”

Further along the step, Adalwolf and Anubis were lost in conversation. Anubis was our pack leader, but Adalwolf always fancied himself as second-in-command, despite our lack of ranks. Fenrir sat by herself, sipping on a glass of pinot noir as she watched the slaughter unfold in the arena below.

War Mutt sat on the sun-warmed stone, and Coyote and I joined her.

“I’m beginning to suspect this might be my last campaign,” she said.

“What?” I couldn’t keep the incredulity from my voice.

She looked at me with her clear blue eyes. “I’m serious.”

“Where’s this coming from, all of a sudden?”

She looked down at her tightly laced boots. “I’m not sure. It didn’t used to be a problem. All the killing, I mean. But lately, since Cold Tor...”

During the siege of the asteroid fortresses of Cold Tor, my siblings and I had used minor ordnance to target civilian population centres. Between us, we’d blown the shit out of six habitation domes. Each dome had housed over two thousand men, women and children, all of whom had died seconds later, gasping and scrabbling in the vacuum of space.

“What are you saying?”

Her image rubbed its chin ruefully. “Does it ever strike you that what we do might be wrong?”

“We follow orders.”

“Yes, but in the grand scheme of things.”

“I don’t know what you’re getting at. We do what we’re designed to do. We are what we were made to be.”

“But we could be something else.”

“Like what?”

Her shoulders slumped. “I don’t know.”

“You shouldn’t let Anubis hear you talking like this,” I told her. “He’ll suspect you’re developing a conscience.”

Warship science wasn’t fool proof. Our brains were human. Sometimes unexpected emotions leaked through. We’d all heard horror stories about vessels that had apparently gone mad from stress, or started to exhibit the symptoms of hitherto unsuspected neurological disorders.

War Mutt scowled. “Don’t be ridiculous.”

“I’m just saying—”

“Well, don’t. If any of us short circuits, I reckon it’ll be you, Trouble Dog. You’re practically human already. It can’t be long until you start feeling guilty for killing so many of them.”

“Get all-the-way fucked.”

She laughed cruelly, and pushed off from the seat. I watched her walk over to Anubis and Adalwolf.

“Definitely tetchy,” I said.

Coyote hugged her knees. She hated it when we bickered among ourselves. “When will our orders come?”

“God knows, kid.”

I sat back and looked up at the blue Italian sky. It would have been peaceful were it not for the ever-present clang of steel against steel, and the occasional snarl of a big cat.

Somewhere beyond that sky, ships were fighting and dying.

I said, “Do you remember the Conscripted Witch?”

“Which one was that?”

“The big carrier in the Cornell system. Anubis took out its jump engines and I blew its command deck to ash.”

The Witch had been one of the Outward’s largest vessels. It had boasted a crew complement of over four thousand enemy personnel, including mechanics and electricians, tactical marines, fighter pilots, cooks, flight directors, medical officers, and several high-ranking officers. It had been an inviting and strategic target, and no match for six Carnivores dropping out of the higher dimensions with every weapon blazing.

Now that carrier, all one million metric tons of it, lay broken on the ice of a small moon circling a dull gas giant. The huge ship’s spine had snapped as it settled onto the small world’s curved surface, wrapping around it like a caterpillar draped over a football. And every member of that crew lay dead and frozen with it.

“Oh yes.” Coyote smiled. “That was pretty sweet.”

“Yeah.” My smile masked a curious hollowness in my chest. I’d been thinking about the Conscripted Witch a lot.

Maybe War Mutt’s doubts were contagious, after all.

“Hey!” Fenrir shouted at one of the distant gladiators, almost spilling her wine. “Don’t just swing that sword around. The man’s got a trident, for heaven’s sake. You’re not going to get near him. Go find a spear.”

She sat back down and grumbled, “Have these people never heard of surgical strikes?”

“I don’t think they’ve discovered gunpowder yet,” I said, “let alone laser-guided smart missiles.”

“Damn savages.” She waved her arm at the centre of the arena. “How do they expect to be able to kill guys with tridents if they don’t have guns?”

“Maybe that’s why they invented them?”

She paused and looked thoughtful. “You might have a point there.”

She went back to watching the fight.

I sat with Coyote for a while, but the distant brawl didn’t interest me, and I couldn’t get comfortable on the amphitheatre’s cold stone step. I had a paperback copy of King Lear in the pocket of my coat. I pulled it out and opened it on my knees. I could feel the warm touch of the sun against my cheek.

“Now gods,” I read aloud, “stand up for bastards.”

On the step beside me, Coyote raised her eyebrows. “What?”

I showed her the book cover. “Shakespeare,” I explained.

“Oh.”

“It’s about this vain old king who renounces his duties, and his daughter, Cordelia.”

“I know what it’s about.”

Anubis and Adalwolf had started walking around the outside of the arena. War Mutt trailed after them.

Coyote asked, “What time do you think they’ll call us?”

“I have no idea.”

“How long has it been?”

I checked the time on my internal system. “About five minutes in here.”

“And in the outside universe?”

“Twelve milliseconds.”

“Dammit, this is taking forever.”

“Sorry.”

She nodded towards our distant brothers. “Do you also want to go for a walk or something?”

I closed the book. “Are you getting bored?”

Coyote pulled her jumper more tightly around her ribs. “Hey, I’m a warship, remember? I’ve been bored since we got here.”

Down on the amphitheatre floor, a pair of tigers took down the guy with the trident. His screams cracked like glass in the air, and I winced. In simulations like these, there was such a thing as too much realism.

At least in space, nobody had to put up with all that screaming.

We started walking counter-clockwise, in the opposite direction to the other three.

Fenrir stayed where she was, drinking wine and watching the fight.

We did two laps in silence.

Halfway through our third, Coyote said, “What’s the name of the place where the battle’s happening?”

“Pelapatarn.”

“I’ve never heard of it.”

“They have sentient trees, apparently.”

“Oh, cool.”

We carried on. Coyote scuffed her sandals on the weathered stone. I kept my hands in my pockets.

“Do you think it’ll be a hard fight?”

I shrugged. “I doubt it. Most likely, it’ll be another bombing run. High altitude, pinpoint targets.”

“So, the usual, right?”

I smiled. “Yeah, easy in, easy out.”

“But for now we have to wait?”

“For now.”

“How long?”

“God knows.”

AN EXAMINATION OF THE TROLLEY PROBLEM USING A SENTIENT WARSHIP AND A ROTATING BLACK HOLE

AN EMBERS OF WAR STORY

Author’s note: This story takes place after the events of Light of Impossible Stars and contains mild spoilers for those who haven’t read the trilogy.

As penances went, life as a combine harvester wasn’t so bad.

Pan had been here for six seasons now, and she had come to love the solitude. Rumbling through fields of golden wheat on thick tyres, her thresher whirring, no other soul in sight between here and the distant, heather-purple mountains, she felt truly at peace.

Once, she had been a test pilot.

In the early days of the Archipelago War, she had been slotted into one prototype warship after another. She had been the first to take a Hyena-Class through the higher dimensions; the first to do a live weapons test in a Carnivore-Class. Then later, as the fighting intensified and the losses began to take their toll, she became the onboard AI for the first of a new breed of fast-response pocket battleships known as the Lynx-Class.

Fully tooled-up and yet still nimbly manoeuvrable, the Lynx had been a delight, and Pan had gloried in it. Up until that point, she hadn’t possessed a name, merely a designation. She took on the name of the ship – the Chaos Panther – and had retained it ever since, even though her operators in this agricultural backwater tended to shorten it to Pan.

As the Chaos Panther, she’d served with distinction in several major engagements – right up until the final mission of the war, when she’d been involved in the Battle of Pelapatarn, after which, damaged and trailing smoke, she had crashed here.

At the time, she had been expecting rescue. Her surviving crew had been airlifted to safety within hours, but nobody came for her. The Navy had other priorities. Mopping-up operations held their attention in a dozen systems. And so, there she lay until one of the agronomic technicians came and offered her another role, piloting this oil rig-sized harvester on its endless annual circumnavigation of the moon, moving with the seasons in an endless autumn, reaping the crops that had grown since its last passing.

And she had learned to be content.

Emotions weren’t supposed to be something to which warships aspired. And yet, they tended to develop in later life. The neural processors at the heart of each AI were based on the cloned neural cells of fallen soldiers, and somehow, that humanity tended to eventually leak out, one way or another. That’s why most ships were young. As teenagers, they could be moulded into reckless, loyal sociopaths and put to use before inconvenient feelings of ennui or guilt began to seep through their conditioning.

Maybe that’s why the authorities had left her here? She was in her mid-twenties now, and subject to a whole range of novel sensations and excitements. Her days as a remorseless killing machine were behind her.

And so, she harvested and found peace beneath the baleful glare of the dead world that rose and set above her. She was doing good work. The grain she gathered and processed would be distributed to many worlds, and hundreds of thousands of otherwise hungry mouths would be fed. The actual operation of the harvester required a fraction of her attention, and the rest she devoted to contemplation and literature.

It wasn’t until the sixth anniversary of Pelapatarn’s destruction that the war finally caught up with her.

It came in the person of a middle-aged man who introduced himself as Ashton Childe.

“I remember you,” Pan said, looking down at him through the cameras on the harvester’s front. “You were Naval Intelligence during the war.”

“I was.” Childe sounded tired, as if the memory sapped him. “Then I defected to the House of Reclamation.”

“Have you come to ask me to join your rescue organisation?”

“No.”

“Then I suppose you’d better come aboard.”

* * *

As a ship, Pan had used a holographic interface to communicate with the crew. Humans tended to respond better to human faces. So much of their communication relied on subtle expression and body language, it was easier to project a human image in order to talk with them. Pan’s image was based on that of a female pilot from the pre-atomic era. She had stumbled on the picture in an old historical archive. The woman’s name had been Shirley Slade and she’d been part of an experimental programme during World War II. In those days, some of the planes had been made of wood and canvas, and Pan reckoned anyone brave enough to take one into the air had to have nerves of tungsten. The picture caught Slade wearing a flying cap and tartan scarf, with goggles pushed up onto her forehead and her gloved fingers holding a half-smoked cigarette to her lips. Her black-lashed eyes stared off-camera, as if gazing at something only she could see. She was the epitome of unflappable bravery, and so Pan had shamelessly stolen her likeness.

She stood before Childe now, kitted out in a brown leather pilot’s jacket, with her hair tucked into the cap, which was fastened by a buckle beneath her chin.

“Hello,” she said.

If Childe was fazed by her appearance, he didn’t show it. “I’m here to make you an offer,” he said.

“Really?” Pan conjured a lit cigarette, and held it so the holographic smoke rose in a twisting column. “And here was I thinking you’d just discovered a burning passion for wheat cultivation.”

The former spook ignored the sarcasm. He said, “I’m here representing a private group of individuals. Very wealthy individuals.”

“Do I look in need of money?”

“I can offer you a ship.”

Pan narrowed her eyes. “You know, technically, I’m still part of the Navy.”

Childe shook his head. “Technically, you’re listed as lost in action.”

“You’ve been doing your homework.”

“So, we could claim you as legitimate salvage.”

“Charming.”

“But instead, I decided to come here so we could talk like civilised beings.”

Pan looked him up and down. Out-of-shape, slightly dishevelled, hollow-eyed. This was a man who had been places and seen things that haunted him.

“Okay,” she said. “Make your pitch.”

Childe smiled. “Look up,” he said. “What do you see?”

Overhead, Pelapatarn’s ruined face glowered down at her like a foggy, accusatory eyeball. What had once been a sentient, world-enveloping forest now lay blackened and scorched. Nothing moved there save the dust. Nothing grew. The planet had been sterilized. And it had been her side that did it. They had done it to wipe out the other side’s top generals, who were holding an emergency summit beneath the talking trees, decapitating the Outward forces and shortening the war by months, possibly years. Countless lives had been saved, but the price had been tragic.

Distracted by the nuclear devastation being rained on the planet, Pan had been hit by a lucky shot from an Outwarder drone platform, and forced to set down here, in the wheat-fields of Pelapatarn’s moon.

“Devastation.”

“Exactly. The final battle of the Archipelago War. The turning point of recent history.”

“So?” Pan took a drag on the cigarette. It was just a hologram and she had no sense of taste, but she liked the way she looked when she did it. Inhaling toxic drug smoke made her feel badass.

“The bombing of Pelapatarn had a devastating effect on the Carnivore-Class ships that participated in the attack. Several were lost, and one, the Trouble Dog, developed a conscience. She went off and joined the House of Reclamation.”

“Again, I have to ask, so what?”

“It was while on a mission for the House that she unleashed a fleet of ancient warships that killed billions of human beings and sterilised entire worlds.”

Pan froze. “Billions?”

“I’m afraid so.”

“That’s awful.”

“You have no idea.”

“I hadn’t heard.”

Childe shrugged. “They went after military technology and infrastructure first, then major population centres. This planet’s almost entirely agricultural, so it wouldn’t have been high on their list of priority targets.” He sighed. “Although, they probably would have got around to you eventually.”

“What happened?”

“It doesn’t matter. The damage had already been done.”

Pan stood silently, trying to digest what he had told her. “And all this was the Trouble Dog’s fault?”

“It was.”

“But why have you come to me? There’s nothing I can do about it.”

“Actually, there might be.”

“I doubt it.”

Childe smiled without humour. “I want you to change the past. I want you to stop the bombing of Pelapatarn.”

Pan stared at him, dumbfounded.

“I’m quite serious. My backers, who wish to remain anonymous for the moment, are of the opinion that it might be possible for a suitably skilled ship to plot a close approach to a rotating black hole that would bring it back to an earlier point in time.”

She ran a quick data search on the theoretical speculation surrounding the idea of time travel. “You’re talking about Gödel’s closed timelike curves?”

“Indeed.”

“But surely, if they existed, they would just bring you back to where you started?”

“Mostly, yes.”

“But you have a different theory?”

“You know scientists, they’re always coming up with new theories and interpretations. And a lot of money has been spent on the research. A lot.”

Pan rolled her eyes. “Go on, then, tell me your plan.”

Childe’s expression hardened. “I’m trying to stop the largest genocide in human history. I don’t pretend to understand the physics involved, but it’s speculated that if you graze the event horizon at the right trajectory relative to the hole’s spin, the curve might return you to an earlier point in your lifetime.”

“That sounds like bullshit.”

“There are pages and pages of calculations. I’ve seen them. I didn’t understand a single one of them, but I’ve been assured the math checks out.”

Pan sucked her cigarette. “And you want me to be the idiot that tests if it actually works?”

“We do.”

Pan stroked her chin with a gloved hand. “Sounds risky, and probably impossible.”

Childe smiled. “It’s got to be better than harvesting, surely?”

“Don’t knock it until you’ve tried it. I’m having a blast here.”

“Seriously?”

“It’s peaceful.” She tapped her chin. “Can’t you send a drone instead?”

Childe shook his head. “The curve takes you back to a point in your own existence. You were there, so you can return. We don’t have a drone that was there, so we can’t send one.” He sighed. “Besides, you were one of the best test pilot AIs we ever had. You can make this trip better than a dumb drone. And when you get there, you’ll need to talk to the Trouble Dog and change her mind. We need you on this.”

“Why would I get involved?”

“You’ll get a sleek new body, and the chance to save billions of lives. What more could you want?”

She used her external cameras to gaze out over the endless fields of gently rippling wheat. The sun was beginning to set and the horizon had deepened into all the colours of a guttering fire.

“Can I think about it?”

* * *

Three weeks later, the Chaos Panther had been installed in a new prototype ship, with her name daubed on the bow in bright orange paint. The ship was compact and stubby, shaped like a bullet, with an uninterrupted, mirror-surfaced hull. There were no antennae or weapons mounts to be ripped away by the ferocious gravity she would encounter. The only crew member was Childe, who had been tasked by his mysterious backers to ensure their plan was a success. He was to be their ambassador to the past. He lay on a gimballed, reinforced crash couch inside the armoured bridge at the vessel’s heart. Ahead of them, the black hole filled the sky. They couldn’t see it directly, of course, but it was outlined in fire by the glow of compressed matter being sucked into its vortex, and the tortured starlight bent around into a halo by its savage gravity.

“Are you ready?” Childe asked. He sounded tired and fatalistic. Having defected from both Naval Intelligence and the House of Reclamation, she guessed he was a man short on options and long on enemies.

“I think so,” she replied. She’d spent the past fortnight putting this vessel through its paces, and knew better than anyone what it could do.

“Then, feel free to proceed in your own time.”

“Is that supposed to be a pun?”

He smiled dryly. “Maybe.”

“How long have you been working on that one?”

“Five days.”

“It wasn’t worth it.”

She fired the engines and the Chaos Panther leapt forwards.

* * *

She returned to consciousness with no recollection of the transit. The sensor recordings from the moment they clipped the event horizon were scrambled and nonsensical. Her own memories were a frightening black absence.

Perhaps, she thought, there are simply some things we have no way to comprehend.

A quick damage check showed that hull plates all along her starboard side had softened under the onslaught of the black hole’s pull, and been stretched like taffy into strange, eldritch shapes.

She could worry about that later.

Ashton Childe lay unconscious on the bridge. He’d suffered a stroke. The medical systems embedded in his couch were doing their best to keep him alive. Pan took a moment to check their findings, and saw the prognosis was good. The burst blood vessel didn’t seem to have caused too much damage, although it would be some time before he could be brought back to full consciousness.

“I guess I’m alone, then.”

She looked out at the stars, and there was no sign of the black hole. Automatic triangulation of known pulsars gave her position to within a few millimetres. She was right where she was supposed to be, in orbit around Pelapatarn. And if the relative positions of the local stars in relation to the galactic core could be believed, she was also six years in the past.

She looked down at the planet, expecting to see the scorched, dust-ridden hellscape she had become used to seeing. Instead, Pelapatarn greeted her in shades of vibrant greens and blues; a living world rich with a thriving, sentient biosphere.

“Well,” she thought, “I’ll be damned.”

She ran a tactical scan and located the Conglomeration Fleet bearing down on this world, preparing for their fateful attack.

All she had to do was broadcast the data she’d been given, showing the ruin and carnage that would result from the Trouble Dog’s actions, but a sudden doubt caused her to pause.

Thinking many times faster than a human brain could possibly manage, she tried to run some calculations, but there were way too many variables.

If she stopped the bombing of Pelapatarn, the war might persist for years, and both military and civilian casualties would continue to climb. But if she allowed the bombing to go ahead, it would kill hundreds of thousands and end the war – only for billions to die later as an indirect result of the Trouble Dog’s guilt.

She instantiated herself on the bridge next to Childe’s couch. His eyes were open but he seemed unable to speak.

“It’s an impossible choice,” she told him. “Either way, whole planetary populations are going to die.”

He looked like he wanted to say something, but only manged to grunt, deep in his throat. Pan put a gloved finger to his lips.

“Shush.”

She turned to the large viewscreen dominating the forward view. In orbit, the battle had been joined. Missiles leapt back and forth like fireflies between the attacking and defending ships. Lines of tracer sparked in the darkness. In those distant specks, humans had already started to die.

She had come to the past, but it was the future that now eluded her. How could she judge what had really happened against what might happen? She knew for a fact that if she allowed events to play out as they always had, there would eventually be a deliverance of sorts, whereas Childe’s plan opened up huge areas of uncertainty, and the possibility of total annihilation for the entire race. Why would he risk that? Was he trying to atone for mistakes of his own? She had no way of knowing or caring what his motives might be.

All she knew was the choice now presented to her.

And the answer was obvious. The main timeline had to be preserved. If she let Childe talk to the Navy and reveal the future, events would be irrevocably changed, with possibly fatal consequences for the entire human race. Too many unpredictable variables would be unleashed. But in order to stop that, she would have to destroy the information she had brought here from the future, to make sure it could never fall into their hands. She would have to destroy it, and herself and Childe along with it, in order to leave humanity in blissful ignorance of the events to come.

History would play out as it had always done.

She took a final drag on her holographic cigarette, and flicked the butt at the stars. Then she released the containment fields around her fuel chambers, detonating the ship in a violent explosion that was entirely lost and unnoticed in the fury of the battle.

FROM THE TABLE OF MY MEMORY I’LL WIPE AWAY ALL TRIVIAL FOND RECORDS

Having just wiped his memory, Kimbrel was feeling philosophical.

“If we cease to remember who we’ve been,” he mused, “how can we know who we really are?”

Amie, who was used to his bullshit, declined to answer. They were sitting at a sidewalk café on a dusty planet close to the edge of the local spiral arm. Stars filled half the night sky, an inky void the other half. She poured another glass of honey-coloured wine and watched the hustle of pedestrians and street vendors as they went about their business.

Across the table from her, Kimbrel wore a long black robe in the local style, decorated with peacock feathers; a matching silk scarf; and a slash of smoky eyeliner. Amie had draped herself in bright scarlet silks; strings of precious stones sparkled at her ears and throat; and even her skin glowed from within, as if infused with golden dust. When meeting another immortal, there were certain protocols that needed to be observed, and one always had to look one’s best.

Kimbrel pushed aside his empty plate, containing the remains of a salad, and sighed contentedly. “Anyway, I’m glad you asked to meet,” he said. “It’s been way too long.”

Amie raised an eyebrow. “We saw each other less than a century ago.”

“We did?”

She rolled her exquisitely made-up eyes. He was like this every time he cleared the recollections of the last thousand years from his mental cache. “You’ve deleted that memory as well, haven’t you?”

Kimbrel’s cheeks coloured. “I would never delete the recollection of a single second in your esteemed company.”

“You say that every time, and yet here we are again.”

“Less than a century, you say?”

“We drank tea on Marrakus, and talked of the different ways that rain can fall, depending on the gravity of the planet you happen to be standing on.”

“We did?”

Amie sighed loudly. “Why do you keep doing this?”

“What?”

“Wiping your memories?”

Kimbrel smoothed the front of his robe with painted fingers. His cheeks were burning now. “So I can experience the wonder of the universe anew,” he mumbled.

“You know it’s not an exact science. Every time you do it, you end up purging more than you intended.”

“Do I?”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake.” She shook her head impatiently. “And now you’ve diverted me from the purpose of this meeting.”

“Which is?”

She looked him in the eye. “I’ve found something that might be of interest to you.”

“Found?” In contrast to his restless itinerance, Amie tended to stay within the same general area of the galaxy. Serious and prone to fits of melancholia, she kept vigil over a loose federation of worlds on which various empires had risen and fallen half a dozen times, and where she was regarded as some sort of goddess. Mambo Sun, her ship-cum-palace, contained art treasures and technological relics from the societies to whose births and deaths she had borne witness, including many statues and other representations of her likeness.

“Let’s just say it drifted into my sphere of influence.”

“Drifted?” Kimbrel’s eyes narrowed with the first spark of interest. “Is it a ship?”

“A very special ship. I think you should come and see it for yourself.”

He pursed his lips. While it was true he had a fondness for unique and interesting starships, and that across the aeons, he and Amie had been friends, lovers, and only occasionally rivals, an immortal never lightly entered the domain of another, however trusted.

“Can we not arrange a virtual tour?”

Amie laughed, setting her strings of amethysts and sapphires clicking and clattering against each other. “Trust me, you really need to see this with your own eyes.”

“Where is it?”

“In the hold of my ship.”

Kimbrel glanced up at the strip of sky between the timber buildings lining the street. “In orbit?”

“Indeed.”

He sighed dramatically. “Okay, then. But you have to promise not to kill me.”

Amie reached over and patted his hand. “Darling, it’s not me you need worry about.”

Kimbrel made a face. He left a handful of coins on the wooden table and let her teleport them up.

* * *

Amie hadn’t lied. The mysterious ship lay in one of the hangars at the rear of the Mambo Sun like a whale washed-up on a beach. Once, it had been an asteroid measuring approximately nine-hundred metres in length and three hundred in width; now, it had been hollowed-out and fitted with engines.

“It’s beautiful.” Kimbrel said.

Amie wrinkled her nose. She thought it looked like an overcooked potato. “It’s what’s inside that counts.”

She led him across the deck to the cratered flank of the asteroid. Under the influence of the Mambo Sun’s artificial gravity, dust and loose gravel had fallen from the rock’s surface and now lay in a thin, crunchy halo on the smooth floor.

“Is that an honest-to-goodness airlock?” Kimbrel asked. “I haven’t seen one of those in millennia.”

“That you remember.”

“What?”

“Nothing.” Amie touched the cold surface of the rock. “This comes from a time before forcefield manipulation and permeable pressure curtains, when they had to resort to engineered mechanisms to stop all the air draining out of their vessel.”

“How fascinating.” Kimbrel looked up at her. “What happened to the crew?”

“They’re still inside.”

“Dead?”

“Cryogenically preserved.”

“You’re kidding me?”

“Actual meat popsicles.”

“Oh, my days.” He scratched his chin, contemplating the horrors of such a crude and dangerous method of preservation. “Can we see them?”

Amie smiled. “But, of course.”

They stepped forward. She closed the outer door and cycled the lock.

“Fascinating,” Kimbrell said again, listening to the hisses and clunks as the air pressure equalised.

When the inner door swung open, the ship’s overhead lights flickered into life, revealing a large chamber filled with antique pressure suits, equipment lockers, and bulky manoeuvring packs. But it wasn’t these historical curiosities that froze Kimbrel in place.

“What the fuck,” he asked, “is that?”

A banner hung above the racks of suits. It was a portrait of a young man in military uniform. Short hair and a line of medals on his chest.

“It appears to be you.”

“I can see that, but why? How?”

Amie’s smile broadened. “There are similar portraits all the way through the ship. Some even come with inspirational quotes in one of the First Languages.”

“The First Languages?”

She gave a happy little nod. “Yes, this ship comes from the Old Place.”

Kimbrel gaped. “That’s impossible. It would have to have been travelling for at least a million years.”

“Close to that.” Amie spread her hands. “Once my ship managed to crack the unbelievably obtuse programming languages used by this old tub, the information contained in the flight computer proved most instructive.”

“And?”

“And this is a rescue mission.”

“I don’t believe you.”

“They were looking for a missing test pilot. Only something went wrong. The ship went off course and never woke them. They’ve slept a million years. After that length of time, I calculate the possibility of successfully reviving any of them to be around fifty-to-one. Maybe lower.”

Kimbrel looked sceptical. “If that was correct, that would make this a find of unparalleled historical significance.”

“You don’t know the half of it.”

He raised an eyebrow.

She smiled. “The test pilot for whom they were searching.”

“What about them?”

“It was you.” Amie arranged her features into a more serious cast. “Kimbrel, it appears you were born on Earth.”

“The hell I was.”

“It’s true.” She gestured to the banner. “You were the first human being to travel to another star. You went out, and you never returned.”

“I… Are you sure?”

“I’ve verified all of this from the records. They left Earth to find you and now, after a million years, after outliving the loved ones they left behind, outlasting their entire civilisation, they finally have.”

Kimbrel stumbled. He put out a hand to steady himself. “I don’t believe it.” His voice was a hoarse whisper.