4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Myriad Editions

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

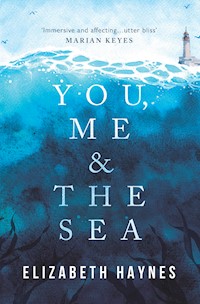

'Immersive and affecting…utter bliss.' —Marian Keyes Compelling, moving and teeming with feral desire: Elizabeth Haynes's new novel is an intoxicating story of love and redemption, set on a wild and windswept Scottish island. Rachel is at crisis point. A series of disastrous decisions has left her with no job, no home, and no faith in herself. But an unexpected job offer takes her to a remote Scottish island, and it feels like a chance to recover and mend her battered self-esteem. The island's other inhabitants are less than welcoming. Fraser Sutherland is a taciturn loner who is not happy about sharing his lighthouse – or his precious coffee beans – and Lefty, his unofficial assistant, is a scrawny, scared lad who isn't supposed to be there at all. Homesick and out of her depth, Rachel is sure she's made another huge mistake. But, as spring turns to summer, the wild beauty of the island begins to captivate her soul.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Praise forYou, Me & the Sea

‘This is escapism in the best possible way. You, Me & the Sea is such an immersive, affecting novel – I absolutely loved it! Escaping to the island setting was utter bliss. I can’t tell you how much happiness the descriptions of the sea, the sky and the landscape brought me. The love story is beautiful; I cared so much about both of them. This book gave me a huge amount of comfort at a very tricky time.’

Marian Keyes

‘I absolutely loved You, Me & the Sea. Its beautifully evoked wild setting, tense, detailed writing, suspenseful storytelling and finely drawn characters work together to make it a very special read. Rachel and Fraser, each such a wounded soul, gradually build an inspiring relationship between them. This immensely deserving novel should be a huge success.’

Rachel Hore

‘I couldn’t put down this amazing book. It’s a comfort and a breathtaking romance – aka sizzling hot! – with beautifully atmospheric scenery. What a perfect escape!’

Alex Brownii

iii

there is

what you think

you are

and then there is

more

L. E. Bowman

The Evolution of a Girl

Contents

Part One

April

2

1

The Island

Rachel

It’s nearly eleven. Rachel is on the boat, the Island Princess, it’s called, churning through choppy grey seas. It’s supposed to take tourists on day trips, so it has seats and a little bar area inside the cabin, and a tiny toilet that smells of diesel and sick. Craig Dunwoody brought her a cup of tea earlier and then went back to the upper deck again, leaving her clutching a steaming polystyrene cup and trying not to spill it. Craig is technically going to be her boss, she supposes, although really she’s employed by the Forth Islands Trust and Craig is just her day-to-day contact, the one who’s going to tell her what to do.

Besides Craig, Rachel and the boat’s captain, whose name is Robert, there were five other people on the boat when they set off, all of them tourists: a mother and father with a teenage son, and an older couple in full hiking gear. People make day trips to the Isle of May, which is closer to the coast, and has seal colonies and a visitor centre. The Island Princess does a circuit, dropping off the trippers at May, then on to the Isle of Must, and back via May to pick them up again. May has two full-time reserve managers and several volunteers doing various things over the summer months. Craig has told her all this.4

Robert doesn’t talk much. He said hello and helped her aboard and that was about it.

The boat had stopped at May after about an hour. It was grey and rocky, with a steep, winding path leading up from the concrete jetty against which they moored. The tourists disembarked. On the jetty a young man in a green knitted pullover, with something monogrammed on his right chest, had greeted them. Rachel had been expecting him to lead the tourists up the path, but he’d waited for them all to get off and then Craig had handed across three of the plastic storage boxes, the sort you use for moving offices, which were then stacked neatly on the jetty. Once the boat began to chug out of the harbour again, the young man had stood on a wooden box and begun to give a talk.

Rachel had watched all of this without comment, dazed with tiredness and the effort of fighting the constant low-level anxiety. She had slept a little better last night, shattered from a day spent on trains and buses, but still she had been awake this morning from about four, worried about oversleeping and waking to find her new employer knocking at the door. As it turned out, he’d had to join her for breakfast, because the bed-and-breakfast (and Dawn, the owner) only started serving at eight. Rachel hadn’t been particularly hungry but she could smell bacon cooking when she sat down in the dining room, and, being the only guest, didn’t want Dawn to have wasted her efforts. So, a full Scottish breakfast, complete with square sausage – a new one on her – and black pudding and bacon ‘from the farm’. She’d left the black pudding, ate as much as she could of everything else. Craig had arrived before the food, and Dawn had made him a coffee. They seemed to know each other well. Maybe he put business her way. The birdwatchers, perhaps.

Craig was okay. Hair that would be called strawberry blond on a woman, wispy-fine and receding; pale blue eyes, freckles, quietly spoken. Very grateful to her for taking on the job, flushed and a little sweaty – he had been up for hours, he said, 5getting everything she needed – and jumping from one topic to the next so that it was hard to take everything in.

‘Don’t worry,’ he’d said. ‘I’ve written all down. You don’t have to remember a thing. And you can phone me if you get confused.’

He’d pulled out a crumpled sheaf of A4, folded in the middle, which had dense typescript on most of it, and notes scrawled over the top in red pen. When he’d spewed forth everything he thought she needed to know, only about a tenth of which she could possibly have repeated had anyone wanted to test her on it, he had taken a deep breath and sat back on the raffia chair in the bright little dining room.

‘So,’ he said, ‘you’re from Norwich?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’ve never been.’

And that was that. A moment later she was sent to grab her backpack from the room while he settled up with Dawn, then he was outside in a battered old Land Rover, the engine ticking over.

At the harbour, which was not very far away, Rachel had helped him stack plastic storage boxes on to the boat, and, once the tourists had piled on, they were away.

Must is another forty minutes beyond May, beyond the Firth of Forth and out into the North Sea. All Rachel can think of is the square sausage and the tea, swilling around inside her. By far the biggest meal she’s eaten in months – what was she thinking? To counter the movement of the boat she keeps a fixed eye on the island as it gets larger, making out details. There are not many pictures of Must online, she’d found when she first searched. There were plenty of pictures of the Isle of May, and so she’s been imagining it as May’s younger sister: more compact, prettier, greener. Instead the island before her is a squat, ugly little thing, a black and green troll crouched in a slate-coloured sea, waves striking it firmly up the arse.

The closer they get to it, however, the more it grows. The back end rises into black granite cliffs, white with foam at the 6lower levels and pale with the guano of a hundred thousand seabirds higher up. She has seen bigger islands. She has seen bigger cliffs. But this one is going to be her home for a few months, and she needs to like it. She needs it to want her as much as she wants it.

Craig leans over the railing above her. ‘Ten minutes,’ he says. ‘How you doing down there?’

‘Fine,’ she calls, knowing she’s probably green, wishing her make-up bag weren’t buried in her rucksack.

She can see more of the island now. The lighthouse is on the nearest side. Further along and about half a mile back is the small bird observatory that houses birdwatchers, and occasionally other people: ecology students and scientists. Her job will be to take care of the observatory, to clean it, and change the beds once a week ready for the next lot. She has to cater for them, too, which is why the Island Princess is loaded with food for the birdwatchers who will be arriving on this same boat tomorrow, not to mention bedding and duvets and other fancy shit that apparently they’re not used to. It’s been sleeping bags and tins of beans they brought themselves, up to now.

Today is Friday. She has just over twenty-four hours to get ready for them.

Rachel looks at the island and tries to imagine living somewhere so very different from the place she has left, her sister’s Victorian house just outside Norwich city centre. She has lived in various student digs, house-shares and flats. She has been in towns but mostly cities since she was a child; while the countryside has never been far away, she has never lived in it. And this is properly rural, seven and a half miles off the coast of Scotland, and even the other side of those seven and a half miles of grey choppy sea there’s barely a town with nothing but fields behind it. She tries to think how far away she is from her nearest Starbucks. Three and a half hours? It’s nearly two hours’ boat crossing. What if something happens? What if she panics?

She gets unsteadily to her feet. Craig moves to the front of the boat, picking up a rope and looping it between his hands. 7There is a funny smell that gets more pungent as they get closer. It smells alarmingly like shit. Like blocked drains.

The boat rounds the south end of the island and chugs through a narrow channel between the rocks. The swell calms and it feels almost peaceful here, the wash of the boat causing huge pads of seaweed to rise and fall without breaking a wave. Out of the breeze the smell of sewage is even more pronounced and she wrinkles her nose.

Through the thickly salt-encrusted window at the front of the cabin she can see a concrete jetty, and a man and a dog standing on it. Even from this distance she can see he’s huge, a real beast of a man, broad-shouldered, beard, short dark curls moving in the breeze. If you were going to picture a lighthouse-keeper – even though that isn’t what he is – then you’d probably picture him. He’s even taller than she first estimated, she realises as Craig jumps across the gap to the jetty and shakes his hand. Craig is over six foot, and this guy is taller still, by quite a whack. He reminds her of someone she can’t quite place.

She smiles at him and waves, but, if he’s seen her, he is pretending he hasn’t. The dog, however, is staring right at her. It’s a big dog, black and shaggy, with the long snout and upright ears of a German shepherd. Maybe it’s mixed with collie. She likes dogs. This is good news. There will be at least one other sentient being on the island, even if it can’t talk and is already affiliated to someone else. For some reason its presence here is comforting.

Fraser. The man is called Fraser. She doesn’t know what the dog is called.

Fraser

You only really start to feel anger once it’s gone cold. Before that, it’s like something outside you, something unexpected: you watch yourself getting angry and you’re almost surprised 8by it, because that’s not you. That’s not how you behave. And then, afterwards, you get the numbness and you think, where did that come from? and it’s almost funny. Or you’d cry if it wasn’t quite so hideous.

And then later, much later, days and months afterwards, the anger hasn’t resolved and it’s fermenting inside you because actually nothing has changed, and then you get sick with it. And you don’t know why. You get what they call a stress-related illness, only you’re not stressed at all, not when you don’t have to go to work and actually at the moment everything’s paid for, so you can’t claim to be stressed. And then they change it to depression, and you think, oh, is this what that feels like? Because you wouldn’t have called it that. You wouldn’t have called it depression.

Even now he hates that word. It implies a lack of control.

Anger, gone cold and hard like a body that’s saponified – turned waxy and soaplike by the passage of water over fat, the passage of time. That’s what anger’s like, when you can’t get rid of it.

They had words, yesterday.

‘You’ve to keep out of her way,’ Fraser had said.

‘Oh, aye? An’ how’m I supposed to do that?’

‘You see her, you talk to her. Just don’t seek her out. Don’t make friends. She doesn’t need friends, and neither do you. Get me?’

He’d understood. Fraser could see it in his eyes, the flash of alarm. He didn’t see it often these days, but sometimes it was needed, that sharp burst of authority.

Rachel

Despite the relative calm of the harbour the boat is pitching, the jetty rising and falling alarmingly as Rachel tries to judge the right moment to jump. The two men are still talking. The 9boat’s engine shifts into some sort of neutral gear and suddenly it’s much less noisy.

‘Aye, but it’ll have to do for now …’ she hears Craig saying.

Robert comes out of the wheelhouse and shouts something across to the two of them and they both laugh. Even though she can hear the words Rachel’s brain cannot form them into any sort of sense and she thinks they must be speaking Gaelic. Or it’s Robert’s incomprehensible mumbling.

The man – Fraser – looks down at her for the first time in response, frowning. She guesses that Robert said she was a southern softy – or even something more offensive than that, judging by the way he’s looking at her.

Fraser leans over and holds out a hand. Rachel mistakes his intention and shakes it, awkwardly, the boat still lurching.

‘No,’ he says, ‘give me your luggage.’

Rachel slips the backpack off her shoulder and tries to hand it to him. It’s too heavy really, for her to lift one-handed, but he takes it with ease, slinging it over his shoulder and offering his hand to her again. This time she takes it and he hauls her up on to the jetty. She loses her footing and for a horrible moment she is dangling from Fraser Sutherland’s arm, her foot between the boat and the jetty as the boat rises again.

He drops the backpack, grabs the waistband of her jeans with his other hand, and hauls her up just in time.

She is left on the jetty, legs still wobbly from the voyage, heart racing with how close she just came to crushing her foot. He’s already turned back to Craig, as if nothing had happened. The dog pushes against her and she looks down into a pair of serious brown doggy eyes. She lets it sniff her hand until it nudges her with its nose and wags its tail and she rubs her cold hand over its head, between its ears. In response it turns and leans the weight of its body against her leg. She feels the warmth through her damp jeans and it is weirdly comforting.

Robert has started moving the stacked boxes into the deck space Rachel has just vacated, and Fraser reaches down and hauls them on to the jetty as quickly as he stacks them. 10They have obviously done this before. She feels she should be helping, but Craig is also just standing there watching them, and it takes them less than two minutes.

Robert raises a hand and says something and disappears into the wheelhouse. It might have been a goodbye, although he’s scarcely spoken at all today.

Rachel has recovered a little. Remembered her manners.

‘You must be Fraser,’ she says, offering a hand again. ‘I’m Rachel.’

He looks at it, takes a firm grip and a gives it a single, rough shake. Turns away before she has a chance to say anything else, hefting up two of the plastic crates as he does so. Pleased to meet you too, she thinks.

The smell is overwhelming, almost stinging her nostrils. She puts a hand over her nose. ‘Does it always smell like this?’ she asks.

Craig waves a hand at four large stainless steel drums that are on the low cliff above them. ‘No,’ he says. ‘It’s the septic tanks.’

‘The what?’

‘They get emptied once every few years. Helicopter comes to pick them up. Due in the next few days.’

Rachel looks at the tanks. Her stomach lurches.

They carry the crates to the end of the jetty and load them on to the trailer of a quad bike that is sitting there. Fraser brings her rucksack, hooked casually over his massive hand. Without another word he climbs on the quad bike and revs it, then bounces off up the rough track. The dog scampers ahead, knowing to keep out of the way, and Craig and Rachel follow, more slowly. It’s steep, and it’s not paved either, but potholed and spotted with grassy tufts and patches of loose stones, which makes it challenging to climb. Craig is trying to talk, something about puffins and gulls, but eventually he gives up. Rachel makes it to the top before he does.

The island is about a mile long and half a mile wide, a rough oval in shape, should you be looking at it from Google 11Earth, which Rachel has done quite a lot in the last week. The harbour and the lighthouse are in the southern half, the lighthouse on the western side, across the width of the island from the harbour. The bird observatory is on the eastern cliff. They follow the path towards it, which undulates along the top of the cliffs. Everything as far as the eye can see is green, and grey, the colours changing as the sun comes out and disappears again. A few scrubby bushes line the path, bent double by years of growing in the wind, and, overhead, seabirds wheel and call. Nearer the cliff, the noise rises until it’s almost deafening. There are almost no level sections to the path. They’re either walking uphill or downhill, and their steps thud on the springy turf. As if the island is hollow.

Rachel has been told already not to stray from the path, for fear of collapsing a puffin burrow. The birds mate for life, and return to the same nest site every year. She read that on Wikipedia. Anxious not to disappoint a puffin couple returning from half a year battling Atlantic storms only to find their home destroyed, she is determined to be careful.

She can see the bird observatory on the summit of the next hill, a solid, squat building with whitewashed breeze-block walls. The quad bike is parked outside it and the trailer is empty by the time they get to it. Fraser emerges from the open door with the dog at his heels, and stares at them as if they’ve been hours.

‘I’ll give you a call, shall I?’ Craig asks him.

‘Aye, or I could leave it here.’ He’s talking about the quad. ‘You know how to use it?’

Rachel thinks for a moment he’s asking her, but he’s talking to Craig.

‘Aye, right enough. I’ll see you, then,’ Craig says, and shakes Fraser’s hand.

And Fraser walks off in the direction of the lighthouse without so much as a glance in her direction. The dog stays a moment longer, looking from Rachel to Fraser’s retreating back as if it’s thinking of staying, then it takes off after him.

‘What’s the dog called?’ she asks.12

‘Don’t know,’ he says. ‘Come inside, hen.’

How many times must he have been here, and he’s never once asked about Fraser’s dog?

The boxes have been stacked in a large, open-plan room. An unattractive kitchen is at one end: badly fitted cupboards, a laminate worktop warped and lifting at the edges, revealing the chipboard beneath. The rest of it is a sitting room with various mismatched chairs and sofas, and an ugly stained-pine dining table, marked with several overlapping rings where people have put mugs down without coasters. Bare wooden benches sit either side of it. The breeze-block walls are decorated with posters of birds and pictures of Highland scenery, and one framed picture of Anstruther harbour with the Island Princess moored in the foreground, the whole thing faded where it’s been in the sun. There is a large, squat woodburner at the far end, and a vast stack of random bits of wood inside a frame which seems to be made out of pallets, nailed together.

The place smells damp, and over the top of that Rachel can still detect the undeniable whiff of shit from the septic tanks.

‘I’ll give you the tour,’ Craig says nervously, perhaps worried by the expression on her face. Although there’s not a lot more to see.

There are three bedrooms: a double, a twin, and the smallest room, which has two bunk beds in it. There is a chilly, cheaply tiled bathroom without a bath – just a shower, a toilet and a sink. There is also a separate toilet next door to it. It feels very much like the sort of hostel you’d stay in when your budget amounted to the next step up from free, and her heart sinks. None of the beds are made. There’s her first task.

‘Right,’ she says. ‘Am I in the double?’

‘I’m sorry?’ Craig answers, confused.

They stare at each other, then he seems to follow her train of thought.

‘Oh! No, hen, you’ve a room in the lighthouse.’ He chortles with laughter – how hilarious that she thought she was staying in the bird observatory! Nobody had actually said anything 13about where she was going to sleep. She had just made that assumption.

‘With … Fraser?’

‘Aye, with Fraser. Much nicer up there, there’s a telly an’ everything. Did you think you were down here, on your own?’

Rachel feels something like the beginnings of panic. ‘You want me to share with a man I’ve only just met?’

She has a particular voice that emerges when things go wrong. It comes from nowhere and it’s a bit high-pitched, not her usual voice at all. It says things, before she has time to think that saying them out loud is probably not a good idea.

Craig looks slightly horrified. ‘Ah,’ he says, lamely, ‘Fraser’s all right once you know him.’

‘But I don’t know him,’ she squeaks. ‘That’s the point.’

For a moment they stare at each other, until she realises that she has no choice. What’s she going to do? What can she do? Run? Get back on the boat?

‘There are other buildings …’ he says. ‘There’s the old lightkeeper’s cottages, the ones we’re thinking of making into holiday lets. Maybe you could look, see if you’d rather stay there. But it’s a lot of work, so for now you’ll have to stay in the lighthouse. And you don’t really want to be all on your own. This is a lonely enough place without making it more so.’

They unpack the plastic crates. Craig unloads everything directly on to the counter, as if he’s in a hurry to get away as quickly as he can. Rachel starts to put things away, but the cupboards are already occupied: ratty cardboard, cobwebs, a packet of porridge oats with a hole in it, its contents scattered. Everything needs cleaning.

As the plastic crates are emptied they are nested neatly inside each other. Rachel had taken her backpack out of the quad’s trailer but now she puts it back in for Craig to cart on to the lighthouse, along with the empty crates, which are going back with the boat.

The birdwatchers have very basic needs when it comes to catering. They’ll do their own breakfasts, and there will be 14bread and ham and cheese and tinned soups and beans for them to make lunch with. Rachel’s catering role comes in the evenings, when she will dish up something simple and hearty. Lasagne. Shepherd’s pie. Tuna pasta bake. Stew. In between groups of visitors, she will change the beds, clean, and do the laundry. Other than that, there is an extensive list of small but important jobs including checking the level of water in the well which provides the bird observatory with water (a dry spell might mean showers are rationed), making sure the generators are stocked with fuel, collecting driftwood for the woodburner when walking on the beach, litter-picking on the beach (apparently plastic items are washed up constantly; there are two huge metal bins by the jetty which are collected every once in a while and taken to the recycling centre on the mainland), and keeping birds out of the bird observatory. It seems they have a tendency to wander in, if the door’s left open. ‘Helping the warden as required’ is also on there.

She had asked Craig about that over breakfast, scanning through the list and barely taking it in. ‘What sort of things will he need help with?’

‘Counting birds, most likely. Ringing and netting. Taking pictures. General maintenance.’

All of these things are whirling around Rachel’s mind, twisting themselves around the notion that she’s sharing a house with a man she’s only just met. A man who, she now realises, reminds her of Captain Haddock from Tintin, if Captain Haddock had been six foot five and built like a wall.

There is a pile of plastic-wrapped duvets and pillows that were in several of the largest crates.

‘You’ll need one set for your bed, hen,’ Craig tells her. She counts them out. There are two double duvets, so she takes one of those and a pack of pillows and separates it from the rest.

They have finished unloading all the boxes and Craig has shown her the outhouse with the generator, and the washing machine, and the heavy iron grating that covers the well. They are back at the quad.15

‘Backsies?’ he asks warily.

Really she would prefer not to have to hold on to him, but it’s a fair walk back to the lighthouse and she’s tired now, still tired from yesterday’s long journey. She throws the duvet and pillows into the trailer along with her backpack, clambers on to the back of the quad and he fires it up, lurching off down the hill and up the other side, nearly tipping her off the back of it. She squeals and grabs at his waist, thinking about helmets and people who’ve suffered brain injuries following quad accidents, never mind miles out in the North Sea; but, by the time she has opened her eyes and looked at the grey-green landscape bumping past, the lighthouse is looming large ahead of them.

He stops the quad outside the lighthouse and kills the engine. Rachel collects her backpack from the trailer, eases it on to both shoulders. Duvet in one hand, pillow in the other.

‘Call me if you have any problems,’ he says in a tone that suggests he might even answer.

He manages an awkward jog down the hill to the harbour. The Island Princess is waiting for him, rising and falling next to the jetty, ready to head back to May to pick up the tourists.

Already thirty-six hours have passed since she left Lucy in the station car park. It feels like a lifetime ago.

Fraser

Fraser is no more keen to share the lighthouse than Rachel is. He has lived here for the past four years, and the way of life has suited him just fine. He isn’t supposed to be on his own, there is supposed to be an assistant, but whoever they were they never appeared and he never bothered to ask, because the answer would have been ‘funding issues’, as it always was. And he’s glad, under the circumstances, to be left to his own devices here. Fraser is not a man who plays by the rules. And, so far, he has been able to do things his way.16

Now, thanks to the arrival of a new manager – Marion Scargill – they have this grand scheme in place to earn money from the island. There have always been birdwatchers, scientists, coming and going and staying in the bird observatory for the odd week at a time. They brought sleeping bags and tins of food and they managed well enough with the list of instructions for how to work the generator and how to check the water levels. They paid a nominal sum towards the island’s Trust and that was fine, everything was fine. And the island wasn’t paying its way; it isn’t exciting or pretty like the Isle of May, or dramatic and close enough to see from the shore, like the Bass Rock – it’s just another island with puffins and shags and razorbills the same as you get everywhere else, only without the scenery or a visitor centre with a working toilet.

‘We were thinking holiday cottages,’ Marion says.

It’s January. Raining and blowing up a storm outside, and he’s at the head office of the Trust, which sounds as though it should be grander than two scruffy offices in a shared building, a bank of mailboxes in the hallway, frayed carpet on the stairs, loose carpet tiles in here. A radiator on full blast, ticking and gurgling.

He stares at her. ‘Oh, aye?’ he says, thinking, here we go. He has heard this before. Marion, the new broom, all teeth and big hair and a suit that doesn’t really fit her. He has nothing against her, right up to the point at which she interferes in the way he manages things.

‘We were hoping to get them up and running in time for the season …’

‘The season?’

‘April to November … or maybe all through the winter, too, if there’s the demand.’

November, he thinks, good luck with that. And why the fuck would anyone want to come and stay on an island that has, quite literally, nothing but birds to look at? There’s no shop, no beach to speak of, not that anyone would want to paddle in the 17fucking North Sea. Birders, they’re one thing – you can trust them to keep to the paths and not trample on ground-nesting birds. They’re generally good at clearing up after themselves, and can be called upon to help with the ringing and the counts. But holidaymakers? With poorly trained dogs and kids and … toddlers? With unfenced cliffs round most of the island?

Not to mention the idea that he is fucking busy enough with his job the way it is. Not to mention that he likes his privacy.

He doesn’t say any of this. Sits and listens and works the muscles in his jaw, hands balled into fists, tucked into his armpits where she can’t see them.

‘You don’t need to worry,’ she says, clearly misreading his silence. ‘We’re going to employ someone to manage it. Starting with the bird observatory.’

He doesn’t want to just keep repeating her words back to her, and he cannot quite trust himself to speak at all in any case, so he stares until she carries on.

‘We’re going to smarten things up at the observatory – sheets and duvets. And we’ll cater for them – hearty meals in the evening so they don’t have to cook when they’re all tired and cold.’

‘Yum,’ he says, a lemon-slice of sarcasm in his voice.

‘It’ll be a long process, of course. We’ll have to get the lighthouse cottages refurbished gradually, but hopefully the new person will manage that as well as catering for our first guests. We’ll aim to have the first cottage bookings by, say, the beginning of July. The bird observatory bookings will pay for it, and then after that it’ll be a healthy profit.’

He almost laughs out loud, but his gritted teeth prevent it. Firstly, she has grossly overestimated the condition of the lightkeeper’s cottages. He can almost smell them now – decades of damp, the mess left by marauding birds, the smashed windows with mouldy chipboard covering them, the old flagstone floors mossy and uneven. No plumbing, no electricity. She will have to get planning permission, and, however much she might want it to happen, that could take a long time. Other people 18have tried to do things with the cottages before – although not, as far as he could recall, anything as profoundly stupid as converting them to holiday cottages – and so far each scheme has been abandoned. Not cost-effective, especially when you have to get all the materials and the construction workers over to the island on a boat. And where are they going to stay, while they’re refurbishing?

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, there is the issue of Someone being employed to manage the bird observatory, as well as this proposed refurbishment. While he is not against this in principle – lord knows he certainly isn’t about to start catering for fucking ornithologists, he has more than enough to do – it’s more a question of who this person is going to be, and where they are going to be living.

He asks Marion, as politely as he possibly can.

‘Oh, in the lighthouse, of course,’ she says brightly, and he wants to smash his fist into the wall behind her.

‘I live in the lighthouse,’ he seethes.

‘Aye, you do, you live there rent-free as an employee of the Trust, and your colleague will be similarly employed and accommodated. The lighthouse has – what is it? Three bedrooms? Or four?’

There is nothing he can say. Yes, there are fucking four bedrooms, if you count the one with the sloping floorboards and the huge damp patch on the ceiling from the broken tiles on the roof. That one’s not what you would call habitable – and the other two are sparsely furnished and chilly, with mattresses that have definitely seen better days. Better decades. Centuries, even.

What Marion has failed to understand is that he has a certain way of life on the island, that he is used to managing on his own. Most of the time there are no birders. They certainly don’t come every week.

There are things he has thus far been able to take for granted. Privacy. Peace. Being in control of things. Miles of rough sea between you and the land, like the widest moat you can imagine, and no drawbridge.19

The other islands have webcams that people online can view and control. So far the Isle of Must has resisted this intrusion, or has been overlooked, to be more accurate. Everything he does on the island, he does without anyone watching. Without interference. Without comment.

He is used to things the way they are. How is he going to manage, having some guy leaving shavings in the sink, drinking his coffee? What about his vegetable garden? What about the chickens?

He talks himself down from near-raging internal hysteria. None of this, of course, is going to actually happen. The birders he’s met and grudgingly interacted with are not the sort who particularly want to be catered for. By the look of them, they probably spend the entire year sleeping in those grubby-looking sleeping bags, moving from one bird hide to another, following migrations and breeding seasons around the coast. They’re not going to want duvets and carpets and a lasagne with garlic bread. They’re used to eating own-brand baked beans cold out of the tin. And they spend their money on fucking binoculars and camera lenses, from what he can tell – and travelling, probably – not on cosy weeks in ‘luxury guest accommodation’.

Marion is talking out of her arse. As usual.

‘Of course,’ she adds, smiling acidly, ‘you could consider managing the bird observatory yourself, as we’ve discussed previously?’

She sees his face. Allows herself a smirk.

‘I thought not.’

By the time she stops talking about recruitment and timescales ‘moving forward’, he’s almost smiling. It’ll be fucking hilarious to watch all of this go tits-up, he thinks. As it inevitably will.

And now it’s April, and Marion’s plans have been set in motion. And this replacement woman has turned up, in a brand new waterproof jacket that swamps her, and boots that have barely had the labels taken off, looking as if a strong gust of wind 20might blow her off the cliff. He thinks she looks pissed off already. He thinks the big cheery hello and the handshake is all a big fucking act.

Rachel.

Rachel

Yesterday morning Rachel had said goodbye to Lucy and Emily. Ian had had to stay overnight in London for a meeting, so he wasn’t there – and she hadn’t been surprised, or disappointed. She had liked Ian when Lucy first got together with him, but then gradually over the six – no, almost seven – years they’ve been together she has decided he is a bit of an arse, and over the past eighteen months this has festered into genuine dislike. It’s probably mutual.

She’s got worse at hiding it, though. It was something that had been on her mind in the past few weeks, one of the list of things she had been musing over, during the long hours of darkness spent trying to sleep.

How it feels to be childless.

The fact that islands aren’t really islands, it’s only the sea that defines them. They’re land, connected to land seamlessly, it’s just that water is over the top.

Things that can only be defined in the presence of another thing.

Mothers are only mothers because they’ve given birth, only then sometimes they’re not.

Lucy cried in the station car park. By rights she should have been at home in a fleecy dressing gown still, because it was early and she had a baby and who could expect anyone to look glamorous at six in the morning when they’d been up most of the night? But Lucy was up and dressed, in snug Boden jeans. She was even wearing a jacket, wheat-coloured linen, artfully creased. She had offered to drive Rachel to the station 21and Rachel had had no intention of turning that offer down, having spent most of her money on the train tickets. Tears were streaking her make-up and Rachel had looked at her with one raised eyebrow, thinking, who the fuck puts make-up on to say goodbye to their sister at six in the morning?

‘Hormones,’ Lucy said, flapping her hand, and Rachel, who in the past few months had not thought it possible that she could find any more reason to be annoyed by her only sibling, had suddenly found she could.

Emily was fast asleep in her car seat in the back. Rachel did not turn to look, although she could smell the delicate scent of her. Milk-breath and soft skin.

‘You’ll be fine,’ Lucy said, as if it were Rachel crying and not her. ‘Email me,’ she said. ‘Every day? And I’ll send you pictures of Emily.’

Rachel wanted to say, Don’t. Sometimes it was easier just to keep quiet. ‘I’d better go,’ she said. ‘I don’t want to miss the train.’

They had hugged awkwardly across the central console. ‘I’ll miss you,’ Lucy said, into her ear.

‘You too.’

And she’d got out of the car, retrieved her backpack from the boot and walked towards the station, trying not to run. It didn’t feel like an escape.

It’s not an escape if you have nowhere else to go.

Fraser

His mobile rings while he is in the kitchen making coffee. It’s Craig, out of breath from tramping back down the hill to the boat. He has left the quad outside instead of putting it in the shed, which is fucking typical. But that’s not what he’s phoning for – he wants to talk about the girl. Woman. Whatever she is – his new lodger. Housemate.22

‘Aye, she’s nervous about sharing with you. Go easy on her.’

‘Why’s she nervous?’

‘Apparently Marion never told her she’d be sharing. She was thinking she was staying in the bird observatory.’

‘And you’re just leaving her here?’

‘What am I supposed to do? Marion will have my guts if I take her straight back.’

‘Fucking Marion.’

‘She looked panicky so I told her about the lightkeeper’s cottages.’

‘They’re not fit for a pig to live in.’

‘Aye, well, I did mention that as well.’

Fraser makes a sound, a giant pissed-off huff.

‘Well,’ Craig says, ‘I’m sure she’ll come round. Just don’t, you know, attack her or anything.’

‘Fucking as if.’

‘I was joking.’

‘Yeah, I don’t find it funny. Why didn’t they just employ a man, for fuck’s sake?’

‘Because it’s not the 1970s, Fraser, you can’t actually discriminate like that any more. And besides, I don’t think they had any other applicants. Funnily enough.’

Fraser disconnects the call and stomps about in the kitchen, wondering whether he is going to have to watch his language around her and be careful not to startle her all the time. It’s been a long time since he has been near a woman for more than a few hours at a time, and he has never actually shared a house with one. There were women on the rigs, years ago, but they had their own quarters and most of them behaved like blokes, which he supposed was their way of dealing with being so vastly outnumbered.

And then there is the other matter. He’s going to have to talk to her about it. He will have to get her on side. He will have to get her agreement, and in order to do that he will have to be Nice.23

Other than that rather crucial detail, he doesn’t have a clue how he is expected to behave.

On his own island. In his own house.

Rachel

Why didn’t they just employ a man, for fuck’s sake?

Rachel stands in the hallway, silent, awkward. Not wanting to be caught eavesdropping on Fraser’s phone conversation. Not wanting their first encounter to be an argument.

Once upon a time she had been good at standing up for herself, and for other people, but she isn’t that person any more. Now she is the sort of person who stands frozen to the spot in a chilly hallway listening to the man she is now living with expressing a sentiment so outdated he might have landed straight out of the last century, and she already knows she is going to have to pretend to not have heard because she isn’t brave enough to say something about it, and if it’s even possible she hates herself just a little bit more.

She waits for further sexist ranting, but there is only an alarming clatter of crockery, as though he’s doing the washing-up in a temper.

Awkwardly she opens the door again and closes it firmly, sniffs loudly and eases her backpack to the floor, dropping the duvet and pillow on to the tiles. She pulls off her boots and slots them next to a series of enormous trainers, hiking shoes and wellies. Her boots, which had felt so huge and cumbersome after the shoes she normally wears, look tiny beside them.

Be brave, she thinks.

‘Hello? Fraser?’

‘Aye,’ he says, and steps out from the kitchen, holding a tea towel and a mug.

Rachel takes a deep breath. ‘Craig tells me I’m staying here.’

‘Aye,’ he says again.24

‘It feels a bit like we’ve just been landed with each other. Accidental housemates.’

He shrugs, and stares. ‘Makes no difference to me. I’m out most of the time.’

‘Well, I guess I will be too.’

He smirks, the first time his expression has changed. ‘You’ll find there’s not gonnae be much for you to do.’

‘No?’

‘You’ll be busy on Fridays and Saturdays and the rest of the week sitting on your arse. Room’s upstairs,’ he says, and turns and heads into the kitchen again.

‘Which one?’ she asks.

‘Any one you like, other than mine.’ And then, as an afterthought, ‘There’s linen and towels in the airing cupboard. Let me know if you need anything.’

She drags her backpack up the stairs. It feels bigger up here, and there are six doors, all closed, along a narrow hallway. The mustard-yellow carpet is thin and badly laid, wrinkled and threadbare in places, the floorboards creaking beneath her feet.

She opens the door at the top of the stairs and finds a bathroom, big enough for a separate shower, a huge rolltop bath that should be trendy but actually is original, rust and limescale staining the ancient enamel in a long trickle from the hot water tap.

It smells of men, of men’s things. Shower gel and Lynx. Damp, cracked tiles, a mirror that’s so filthy she can barely see her reflection. Black mould has been wiped off the tiles around the sink, settling into the grout. She looks at the toilet, seat up. Can’t quite bring herself to look down into the pan because she already knows it won’t have seen bleach in a long while. Lowers the seat and wipes it with a wad of toilet paper before using it.

Next to the bathroom is the airing cupboard. She moves on to the next door.

It’s clearly his room. She shuts the door again quickly.25

That leaves three rooms to explore, and after a few minutes she sees that she has the choice of a large double the other side of the bathroom, with blue flowery wallpaper, a wardrobe that looks like the gateway to Narnia and a basin in the corner which hangs at an angle off the wall; a smaller room at the back with bare floorboards, a bed with a stained mattress and a large damp patch on the ceiling; or the room next to his: yellow wallpaper, a flat-pack wardrobe and a chest of drawers, a view over the harbour from the large sash window, and a cast-iron double bed with a mattress that at least looks newer. There is a blanket folded on the armchair.

She sits on the bed in the yellow room for a while, wondering if she should go and sleep in the bird observatory tonight at least, when there’s nobody in it. There is a moment where she thinks, not for the first time: what have I done?

She pulls her phone out of her back pocket and looks at it, thinking that she might have a message from Mel or even Lucy, something to take her mind off the fact that she’s on a rock miles from anywhere and so far out of her depth she’s in danger of drowning, a little bit.

No signal at all. Not even one bar.

Ten minutes pass with her staring at the wallpaper, then she forces herself to get up. In the airing cupboard she finds several sets of sheets and pillowcases, chooses one. It smells clean but a little musty. Once the birdwatchers are settled in she’ll wash it, she thinks. Freshen it up a bit.

When the bed is made up with her new duvet everything feels a little bit less awful, and the sun comes out and floods the room with light. She goes to the window and looks out through the salt-washed glass over to the jetty, the sunlight twinkling on the surface of the water. The Island Princess has gone.

She has a sudden pang of something: a gasping panic, a fear of falling, a fear of drowning, a fear of being trapped somewhere small and dark and tight. Strange, when actually she’s somewhere so open. The room is big and airy. And yet she feels cornered, trapped. Alone. Not alone enough.26

Islands are only islands because of the sea over the top of them, she tells herself again. I am still connected to the land, the same land that stretches all the way home. To Lucy, to Emily, to Mel, to Mum and Dad.

She gets a few things out of the backpack to try and make it feel a bit more like home, but quickly gets bored with unpacking. Besides, she might not be here for long. It’s only until Julia takes over. That might be anything from a few weeks to a few months. She doesn’t want to start to feel at home only to get her marching orders. She takes the present out of her bag, the one Dad gave her from the drinks cabinet before she left. Does Fraser deserve it? He’s clearly a misogynist, after all. But what’s she going to do, drink it herself?

‘It’s a good one,’ he had said to her.

‘Dad! You got that for Christmas.’

‘Never mind, I’ll get another. Can’t hurt, you know,’ he said opaquely, ‘to oil the cogs.’

When she leaves the bedroom she can smell freshly brewed coffee. Fraser is in the kitchen and there is a large filter coffee machine, and a grinder, and a bag of beans. He is leaning back against the worktop with a mug in his hand. The dog is lying in a dog bed near the range cooker, head between its paws, looking at her.

She gives him the whisky and thinks he likes it. She is careful to say that she brought it for him, rather than bought it. After what she overheard, she wouldn’t spend money on a gift for him, and now begrudges her dad losing his Christmas present.

‘What’s your dog called?’ she asks, and adds, to make a point, ‘Craig didn’t know.’

‘Bess,’ he says.

At the sound of her name Bess lifts her head and looks at her master with those brown, intelligent eyes. Rachel drops to one knee and Bess wags her tail and dips her head so she can fuss her.

‘Hello, Bess,’ she says. ‘You’re a good girl, aren’t you?’27

‘Made you a coffee,’ Fraser says. What he means, of course, is that he made himself a coffee and there is some left over. She is not fooled.

‘Thanks.’ There is a mug tree so she helps herself, finds the fridge and adds to the cup from a bottle of semi-skimmed. Then takes a deep breath and decides to get it over with.

‘So, this is weird.’

‘Aye,’ he says, drinking.

‘I’ve never moved in with someone I’ve just met. It’s like I’m in your house.’

He shrugs. ‘It’s not my house. I just work here, same as you.’

‘Do you get your own shopping? I mean, do I owe you for the coffee and the milk?’

‘I buy the coffee beans because if I asked Craig to get them he’d get the cheapest ones.’

‘So I do owe you for the coffee.’ It was good, though. Best she’d had in ages, better than the cafés back home, and some of them were supposed to be all that.

‘Don’t worry about it. Unless you’re planning on drinking ten cups a day.’

‘I’ll have tea,’ she says, getting back to her feet.

Bess looks up at her, and across to Fraser, confused by this new dynamic.

They stand there in silence for a while. Rachel has the distinct impression he’s a man of very few words, and for her part she can’t think of anything to say. She is not usually like this. She wants to say, This isn’t me – normally I’m chatty and sociable. But is she? She’s been changed so much by everything that’s happened. Maybe the island will suit her after all. Maybe she will learn stillness. How to live with herself.

But you can’t say any of that to a man you’ve just met, can you?

Instead she says, ‘Can I see the lighthouse?’

Fraser leads her back out into the hallway. She had not paid much attention to the layout on the way in, so distracted was 28she by the phone conversation she had overheard, but now she sees there are three doors other than the one to the kitchen.

He opens one of the doors, which leads to a smallish living room, a threadbare sofa with sagging cushions, two mismatched armchairs, a woodburner with a stack of logs in a basket next to it, a flatscreen TV on a table next to it.

‘Cosy,’ she says, for want of something to say.

‘That’s the radio,’ he says, pointing at some electronic equipment on a table behind the sofa.

‘Oh,’ she says.

‘I’ll have to show you how to use it. It’s for the coastguard, if there’s an emergency.’

‘Is there no phone signal, then?’

‘Sometimes not in a storm.’

‘Do you have to use it often?’

‘Not really. We test it once a week. But you need to know how to use it, in case.’

He shuts the door again, while she’s still wondering what sort of emergency might take down Fraser and leave her the only conscious person able to summon the coastguard, and swallowing down a fresh burst of panic.

Maybe he sees the look in her eyes, because he adds – which doesn’t really help – ‘It’s not just for us to contact them. Sometimes they contact us, too. There’s a pager that goes off, in case we’re out of the building.’

‘Why would they contact us?’

‘Emergencies. You know,’ he says, vaguely.

The next door, to her surprise, leads down a step into a space with nothing inside it but a huge spiral staircase, and a second door in the far wall. The hallway is cold, the chill of the stone and the height and the openness of it all.

‘Where does that go?’ she asks, pointing at the other door.

He doesn’t answer, but opens it. Beyond is a sort of workshop, not a garage because there isn’t a car, but that sort of thing. There is a space in the middle that she guesses is where the quad bike is housed when it’s not in use. Beyond 29that, Rachel can see piles of wood offcuts, toolboxes against the wall, a ladder on hooks, double doors at the back which are propped open. Outside she can see sea, and sky.

‘Right,’ she says.

He begins to climb the stairs, and she follows him.

It’s a long way up, but there’s a landing just below the halfway point. He stops there and she thinks he’s trying not to show he’s out of breath. Indicates the window, and she looks out as best she can through the salty glass at a rather empty view: a bit of land, a bit of grey sea, a bit of grey sky. Wonders if she’s supposed to be noticing something.

After a moment or two he continues up the stairs. They’re getting narrower, and, just when she’s at the point of thinking he’s going to have to pause for breath again, the stairs end on a small stone landing. There is a metal stepladder fixed to the wall, and a hatch. He climbs up through the hatch, and she follows.

‘Wow,’ she says.

Up here there is a view, a proper view. She can see for a long way, even if it is much of the same sort of thing: choppy grey seas, a cloudy sky with a shaft of brilliant sunlight breaking through over the mainland, which looks, from here, closer than you might think.

‘May,’ he says, indicating a long, flattish island to the west. ‘That’s the Northumberland coast, over there. And that’s Fife. And the rest of it, well, nothing between us and Scandinavia.’

‘It’s amazing.’

She turns to the light – the lamp – which is a nest of interlocking glass facets, brilliantly clean and beautiful, and the big glass bulb behind it.

‘And you don’t have to do anything? It’s all automated?’

‘Aye. An engineer comes every three months.’

She’s momentarily distracted by the birds, hanging on the air outside the lamp room, suspended on invisible threads.

‘You can see whales, sometimes,’ he says, as if he’s suddenly wanting her to be impressed.30

‘Really?’

‘Aye, great pods of them. Minke, orca. Sometimes even humpback.’

‘Gosh, I’d love to see that.’

‘Maybe you will, while you’re here.’

‘What about the stars?’ she says, turning back to the view. ‘I bet you get a brilliant view of them on a clear night, don’t you?’

‘Aye,’ he says, flicking a glance at the enormous light bulb right next to her. ‘You should come up here and have a look.’

Now he’s teasing her. She remembers the comment about employing a man, and stiffens. Stares him out.

‘Craig said something about some cottages,’ she says.

‘Aye, look. See where the loch is? Next to that.’ He points, but all she can see is rooftops and a dark strip of water.

‘Can I go and see them?’

‘Help yourself,’ he says. ‘They’re in a state, though.’

‘A state?’

‘They’re basically derelict.’

She takes a deep breath in. One woman’s derelict is another woman’s in need of updating, she thinks.

‘Perhaps I can have a look later,’ she says, turning away. ‘I’ve got the bird observatory to sort out.’

Rachel

There is a surprising amount to do. She is too tired, really, but she can’t leave it all until tomorrow morning, and besides, what’s she going to do until bedtime? Hang out in the lighthouse with Captain Grumpy?

Rachel makes a cup of tea and sits down with the sheaf of notes Craig left her. At the back is a hand-sketched map of the island, and a printed list of the names of the people who are arriving tomorrow. Five of them. All men. There are no dietary requirements.31

Among the notes is a list of suggested evening meals. Jacket potatoes, spag bol, chilli; egg, chips and beans. There are recipes for the spag bol and the chilli. Nothing too complicated, but cooking for six is a bit more than she’s used to. Hopefully none of them are going to complain. At the bottom of the meals list someone has written, in a different handwriting, ‘BATCH COOKING IS YOUR FRIEND!!’

The following page is about the internet and how to reset the router. Rachel pulls the phone from her back pocket and tries to connect to the bird observatory’s wifi, eventually finding the router in the cupboard and resetting it. Green lights come on. Her phone connects, and pings for a few minutes as emails and notifications come through. Mel, Lucy, Ian, various bits of spam. She puts the phone back in her pocket. It would be too easy to sit here and work through all that; she has things to do.

There’s a weird smell in the bedrooms, and it takes a while to identify that it’s the mattresses, that smell of manmade fabric that has got damp and dried again very slowly. She opens the windows in each of the rooms, and the wind blasts in. Cold, salty, tangy – only marginally better. She goes back to the kitchen and begins a shopping list on the back of Craig’s note: Febreze. Some kind of air freshener. It would be hilarious if one of those ‘sea air’ scented candles turned up, she thinks, smelling nothing like the actual sea air, which in reality has heady notes of drying seaweed and fish.

It is Rachel’s job to make the bird observatory a little more civilised. Those were the words Marion had used: make it look a bit more like an upmarket holiday let, and a bit less like a hostel. She had tried to sound enthusiastic on the phone; interior design is not really her thing. But it is Lucy’s, and the week before she came out here they spent a whole evening discussing fabrics and colours and ways to ‘zhoozh’ things up. Rachel has never really known what that means. Perhaps if she aims to make things look like Lucy’s house it will be a good start.32