Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

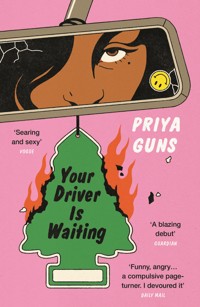

'What you are about to read is a call to arms. Best to prepare for a confrontation.' New York Times Book Review 'A hard-hitting masterpiece. I devoured it.' Kristen Arnett, author of WITH TEETH 'A madcap story you won't want to put down' Rachel Yoder, author of NIGHTBITCH Damani is tired. Every day she cares for her mum, drives ride shares to pay the bills and is angry at a world that promised her more before spitting her out. The city is alive with protests, fighting for people like her, but Damani can barely afford - literally - to pay attention. That is until the summer she meets Jolene and life opens up. Jolene seems like she could be the perfect girlfriend - attentive, attractive, an ally - and their chemistry is undeniable. Jolene's done the reading, she goes to every protest, she has all the right answers. So maybe Damani can look past the one thing that's holding her back: Jolene is rich. And not only rich, but white, too. But just as their romance intensifies, just as Damani learns to trust, Jolene does something unforgivable, setting off a truly explosive chain of events. Brimming with heart, humour, and rage, Your Driver Is Waiting is a powerful, blackly funny social satire that announces the arrival of a fearless new voice.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 322

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Your Driver Is Waiting

Your DriverIs Waiting

PRIYA GUNS

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Priya Guns, 2022

The moral right of Priya Guns to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 426 0

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 572 4

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 427 7

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

If those who have do not give, those who haven’t must take.

A. Sivanandan

For all of us

Dear reader,

Please, always drive responsibly.

1

If you’re going to be a driver, you’d better hide at least one weapon in your car. Especially if you’re a driver that looks like me. Not because I’m dashing or handsome, but because I am a woman, of course. I think it has something to do with tits even though not all of us have them. I sort of do, but that’s beside the point.

I’d been driving for RideShare using Appa’s old car, whose make I will not disclose. I had a switchblade in the glove compartment (which I normally kept in my back pocket), a tire iron under my seat, pepper spray by my door, and a pair of scissors under the mat by the pedals, taped down to avoid any sliding. In the trunk there were six bottles of water, a bucket, a bottle of bleach, some rope, a baseball bat, a few rolls of paper towels, a can of antiperspirant and another of spray paint, some condoms, tampons, pads and diapers. As humans we have an assortment of bodily fluids and by then I’d tasted about eight of them. In the bucket – and I didn’t like keeping much in it – there was a roll of duct tape because duct tape will do just about anything you want it to. I also had some dishcloths, a towel, a crowbar, cleaning products, a toothbrush, baking soda, vinegar, and a squeegee buried under some rags in a corner of the trunk, because things got messy. Oh, and there was a pair of black rubber gloves too. These were difficult to find, but I wanted black.

All the drivers I’ve ever met say it’s crucial to drive prepared. Go ahead and ask one. If they tell you there’s not even one weapon hidden in their car, they’re lying. As a driver, you have to protect yourself. Out there in the city, we’re on our own.

2

I had only closed my eyes for a second and in this new place behind my eyelids, my hair was made of peacock feathers and I was riding a silver pony. The world here was simple. Smiley sun, fluffy clouds, grass that was greener than green on all sides. Then my head hit the steering wheel and I woke up to a long annoying honk reminding me that I was logged into the app, on the road, and in traffic. The driver behind me in a green hybrid flailed his arms around like he was late for his yearly dick suck.

‘Fucking drive, bitch!’

‘All right, all right. Good morning to you too,’ I murmured to myself, smiling at him in my rear-view. Of course I am allowed to nap – maybe not stuck in traffic, but if it happens it happens. I’m sorry?

My morning routine was straightforward. I wish I could say I started the day with the four highly effective habits of the wealthy. You know, they wake up at five a.m. and go for a walk without a care in the world. They brush their horses in their stable, masturbate at the breakfast bar in the house they own on their private island that they flew to on their personal jet. But I had too much work to do. I had no kids, no pets – just one job and a whole load of responsibilities. I mean, I’d love to wake up earlier and smash out a few sets. Only, I get home at two or three some mornings, struggle to sleep most nights, and am up again by seven. That’s not enough hours to properly rest my muscles, my mind, or even my thoughts.

It had only been about ten minutes since I left the house, and my phone was already buzzing. It was Amma. I hit ‘end’ as I always did, wishing that sometimes it had more power than just ignoring a call. Again and again, her name flashed on my screen, and each time I did the same. Then she sent me the first round of the many messages she will send in a day.

7:57

We need $350 for the electricity bill. What happened to minimum payments?

7:59

Rent. PAY RENT OR WE SLEEP NO WHERRRRRE!

8:00

Did U pay last months?

8:03

Garlic Causes Blood Clots – click here – SEE I TOLD YOU!

8:03

Dont drive like a crazy today

8:04

Bye

They say mothers are in tune with their children even if the relationship they have with them is beyond what one might describe as ‘shitty’. Amma was sure that she knew me inside and out when she couldn’t even remember how to function like she used to. Somehow, she believed life was more draining for her than it was for me.

3

‘That’ll be twenty-three twenty-five.’ She must’ve been twenty-three herself, and there she was judging me as I glanced at the items on the conveyor one last time. Iced coffee in a can, ginger ale, actual ginger, garlic, onions, cold rub, chilies, Epsom salts, two vanilla protein bars, dates and some chocolate almonds. Twenty-three dollars and twenty-five cents. I’d need to either do two short rides or one in high surge to make the money back.

‘I don’t need these actually.’ I pushed the almonds to one side, knowing I’d regret it later.

The fluorescent lights in the shop were stupefying. I had noticed, in my quick perusal, that the organic foods were no longer in a separate section, but now had an aisle to themselves directly opposite the value options. On the left, a can of baked beans for half a dollar. On the right, a can of baked beans for three-fifty. Someday I’ll buy one just to know what they taste like. If they melt in my mouth without a hint of aluminum, then they will be worth every penny. But if you’ve got culinary talent gurgling in your veins like I do, you don’t need the organic shit to make something near-genius.

Row upon row behind me was packed full of boxes, bottles and Tetra Paks coloured in wisps of every hue: 100% Juice, Completely Sustainable, Ethical Made and Sold by Cherubs in Fancy Dress, No Orangutans Were Killed in the Process, Fair Fucking Trade. Nothing about any of the exchanges in this hellhole was fair. The city was trying to fool us all.

The old woman waiting for her turn behind me smiled while I rummaged through my pockets for another few coins. She wore yellow high socks and held a bag of oranges in her hands, with some milk and a packet of raisins. I was beyond any point of embarrassment that would allow me to care what she or the twenty-three-year-old teller thought of my grown self looking for more money in my lint-filled pockets.

‘You can never find those coins when you need them,’ I winked at the teller.

‘And don’t they just love to hide. Did you check your back pocket? In your shoe? In your bra?’ The old woman jested at my expense, laughing jovially at my predicament. She had had her fair share of living too seriously, it seemed – she threw jokes into the air as if she was going to die tomorrow. I plopped the change I found in my back pocket on the counter. I had hid a twenty-dollar bill in my hand and pulled it out from my hair. The old woman slapped her knee with the bag of oranges and I worried she’d fall over. She chuckled and I could tell she had been a smoker. I nodded at the teller, smiled at the old lady and grabbed my things. My phone vibrated. The shopping bag with all my twenty dollars and twenty cents’ worth of goods probably weighed about four pounds.

Outside there were kids playing in the street. Good for them, I thought. Better than losing their minds in front of a screen. But their motor skills weren’t fully formed. Their lanky arms and oversized palms clapped haphazardly into the air, missing their ball every now and then. All I could see were my wing mirrors cracking, and if that were to happen it would be another bill on top of the bills I already could not afford – even with Shereef’s discount at the garage – stacked on the kitchen counter.

‘Watch it, kids. Don’t play near parked cars.’

‘There are cars everywhere, lady. We’re all gonna die!’

Kids these days are so well informed. I got my phone out. ‘Hello, one sec, Amma. I’ll call you back.’ Key in the ignition, I took a deep breath. The first of many for the day. A traffic light ahead, a left then right turn before waiting at a school crossing. I could do this drive in my sleep, but I wouldn’t, of course.

It was 8:16 in the morning. Mrs Patrice’s bingo started at nine and she was usually my first ride of the day, and my favourite (5.0 stars). She had on her thin taupe trenchcoat with a motley-coloured scarf tied round her neck. I could smell her musky amber perfume even as she walked down the steps of her building. She was slow, so slow that most mornings I had time to smoke a whole cigarette before she got to the car.

‘Good morning, Mrs P.’

‘Morning, Damani. I brushed my teeth before I had my orange juice. Absolutely the worst damn thing to do.’

I ran over to help her. Her nails were long and filed to an almond-shaped tip. In my hands, hers were soft orchid petals. Mrs Patrice shouldn’t walk and talk simultaneously, and if you speak to her for ten minutes you can see why. Not when you’re eighty-seven and Death lurks at every corner; not if you still want life to spark a light in your eyes. Yet Mrs Patrice didn’t seem to understand.

‘Oranges and raisins in the morning are a thing, I heard, at least for people who can’t afford prunes.’

‘Everything’s a thing these days. You haven’t had any breakfast, have you?’ she asked. The fact about old people is, even when they look like they’re about to fall to the floor in pieces, they know stuff. Mrs Patrice held my arm and looked deep into my soul with her milky, cat eyes.

‘I’ll have something as soon as I drop you off,’ I said.

It was 8:19. Bingo was only ten minutes away, but from months and months of trial and error, we’d worked out precisely how long it took to get her in on time. Mrs Patrice needed to put her coat away (eight minutes), pick up a coffee at the breakfast table (four minutes) and make it to her lucky seat (sixteen minutes, by the time she’d greeted everyone she passed) beside Humphrey who was developing an alarming number of liver spots on his face, and Violet who apparently believed heaven was in her granddaughter’s left eyeball. This left three minutes for me to get her into the car.

Mrs Patrice looked through her handbag – an aroma of lavender bursting free – and handed me her weekly pills, categorized by day, with some floss, Tic Tacs and a pack of peppermint chews. She didn’t use the app, so she handed me ten bucks before pulling out a jam-and-cream-stuffed croissant sealed in its packaging.

‘Here. It’s not illegal to eat and drive these days, is it?’

‘I don’t even know, Mrs P.’ I opened the door and held her bag so she could comfortably make a nest on my backseat. She leaned forward. Her nostrils flared. She didn’t even need to sniff.

‘What died in your car this time?’

‘It smells?’

‘Like a skinned skunk.’

I had forgotten to buy a car freshener – I’d have to pick one up at Shereef’s. I opened Mrs Patrice’s bag and grabbed a handful of mints. She slapped my hand. I popped one in my mouth.

‘It’ll stop any nausea. It’s an actual thing, I heard.’

4

Shereef was in love with Stephanie and thank the gods for that. He was a mechanic by day and a driver at night. Stephanie, who I’d known and loved for most of my life, was a tutor by day, and occasionally a go-go dancer at night. Most people in the city got paid to do one thing, but did something else on the side. Low-paid jobs and unfulfilling work are both exhausting. Even though I just drove, I had dreams that I was saving up for. Driving wasn’t going to be my forever, somehow.

‘Five years today,’ I greeted Shereef who was wearing his sharp grey boiler suit. The top three buttons were undone, as they usually were, revealing his chest hair and a thin gold chain. He beamed, hugging me as I got out of my car, his hands already soiled with grease. ‘And look what I brought,’ I said, chewing dates I wished were almonds covered in chocolate. I passed him the tray, the skins of the dates like thin cockroach skin, the sweetness, a nutty caramel. He took one and threw it in his mouth. We stood outside, staring at my car, chomping.

‘You remembered, D.,’ said Shereef, while using his tongue to dislodge a sticky bit of date from his back molar. ‘It really hit me last year, that I stopped drinking because of this shop.’ Shereef smacked his lips with each bite. ‘My shop, Doo Wop, Steph, you.’ I could tell by the slight glint in his eyes that he needed this conversation; he wanted to dwell on it, but I wasn’t going to let him be that sentimental so early in the day. Grinning, I picked up one of the oily cloths on the workbench nearby and stuck out my chin with a sensual pout. I sashayed towards him to the beat of KRS-One playing from the speakers in the garage, the background music to our conversation. I raised my right eyebrow, doing my best impression of Shereef:

‘ “My grandpa left me five grand when he died. Did I use it to get wrecked? Nah! I put it towards this shop. My shop. Shop of all shops.” ’ I took a bow.

Shereef laughed: ‘You’re such an ass.’ He shook his head, showing off his dimples. ‘Date?’ he asked, still smiling, holding out the tray to me. I took one. ‘But seriously, remember when I used to fix cars on our street?’

‘You fixed mine when it was my dad’s,’ I said, coming down from the high of my performance.

‘Yeah, I did. He kept it well. Smelled like aftershave and deep fry, but still smelled good.’ My throat tightened and I nearly choked on my date.

‘You got any milk?’

‘Five years sober,’ Shereef repeated while he walked over to the fridge tucked in the far corner of the garage. From where I stood it looked as though he was sticking his head inside it for air. He walked back towards me with a vanilla shake. ‘I learned how to take apart every bit of my grandparents’ 1988 Firebird, then put it back together. That’s talent, right?’ he asked, passing me the bottle.

‘Mediocre talent, maybe. Not rocket-science talent.’

‘You can pay for that shake if that’s what you think.’

The garage was in an industrial complex just three minutes from the highway, in an area that lacked all character and charm. It had a colour palette that was as inspiring as the dried gum on my shoe. A kid in our neighbourhood, gifted with the skill of graffiti, had painted a whole mural on the two garage doors of Shereef’s shop, making it a reason for people to drive through the area, even if their vehicles were running smooth. There was a lion in the foreground with a chewed-up leather strap in its mouth, and a Cadillac DeVille Classic driving off into the sunset towards the horizon. Of course, you could only see the masterpiece during off hours, so Shereef made sure there was a picture of it framed beside the open sign because clients were always asking to see it. Beside it, there was a framed picture of the artist. Most people assumed it was there because the boy, named Fonzo, had died, but he was alive and in college somewhere.

Shereef licked his sticky fingers, unbothered by the grease that stained his hands. He walked around my car with the tray of dates, looking up and down the body. ‘Just an oil change today but you can never be too sure what else needs working on,’ he said. I popped the hood open to look at my engine. Shereef rubbed the dent near my front lights, placed the dates on the roof of the car, and pulled out his notebook from his back pocket. I was sure he added ‘FIX DENT’ on the list of things he planned to do to my car, under my name on the page he dedicated just to me.

‘I snoozed a few nights ago. Hit our street sign,’ I confessed.

‘That was you?’

‘You see how the sign leaned back? Like it was relaxing for me.’

Shereef laughed as he walked towards the garage again, cracking his knuckles along the way, which he did too often. I worried that someday they’d be the size of ping-pong balls. In the garage, all of his equipment was pristine and in place. What he needed was labelled and organized in alphabetical order. He brought out a jack stand, a filter, oil and whatever else he had in the kit he wheeled over. He moved as effortlessly as if he was making a sandwich.

‘I was logged on for more than thirty hours last week, drove for maybe twenty, and I made half of what I would’ve made last year for the same hours.’ He wiped his hands with the dirty rag he kept in his pocket as oil spilled into a pan under my car.

‘I know I owe you for the past few visits,’ I said.

‘Don’t worry about that, but pay attention to your rates.’

‘I can’t feel my legs at the end of the day, sometimes.’

‘Trust me. No one’s getting their usual rate while passengers are complaining fares are up.’

‘I don’t see much passenger info these days.’

‘Exactly. They’re taking money from all of us thinking people don’t talk. The rate per kilometre keeps fluctuating and a couple drivers said they haven’t been paid.’

‘What?’

‘Yeah, man. People are getting deactivated for nothing, too.’

‘Like we don’t have mouths to feed.’

‘Trust me.’ Shereef stroked his beard pensively. ‘Are you working more nights?’ he asked.

‘Oh, yeah.’

‘And it’s busy downtown. You notice the protests?’

‘Hard not to.’

‘You see how every day they’re getting bigger?’

‘Like wildfires.’

‘Yesterday I saw an anti-sport hunting protest, a climate strike, and one for trans rights, all together.’

‘That’s pretty cool.’

‘It’s amazing. I’ve been thinking, we need to be out on the streets too, you know. Demand higher rates. Do something.’

‘Yeah. Do something,’ I echoed in a yawn of fatigue.

‘Drivers are driving more and making less. I’m five years sober today. That’s a big deal.’

‘For sure.’

‘I know I can do more.’

I took the pack of cigarettes from my back pocket and lit one, watching Shereef’s two other mechanics with their clients, hoping I wouldn’t set off an explosion with my lighter.

‘If we want some cake,’ he said, ‘even if it’s only a slice, you think anyone is going to give us any? No one out there is going to feed us a crumb.’

I inhaled and exhaled, watching the smoke from my mouth make a billowy cloud above me before it dissipated in the air.

‘I guess,’ I said, because I was completely out of my depth and surviving on flotation devices that may as well have been punctured. Ever so slowly, I was sinking with Amma’s voice in the background: ‘Did you pay the rent yet? Can you turn the TV on? My legs hurt from sitting.’

‘I’ve been speaking to a lot of drivers who pass through here. We’re going to have a meeting. Imagine if everyone working in transport went on strike. The city would freeze to a standstill. You keep yawning, D., do you get what I’m saying?’

‘Of course. I’m just tired.’

‘You’ll be there, though?’

‘For sure. Any time, anywhere.’

‘We can’t wait for a disaster. There’s still so many people in this city who are comfortable. As long as they’re all right, they don’t care about the rest of us, you know what I mean?’

The oil draining from my car came out in a hypnotic stream and I wanted to close my eyes and sleep somewhere just as black.

‘My ma threw up on me last night. Probably because I stank of my last passenger’s vomit,’ I shared.

‘Ah, that’s the smell?’ Shereef walked over to his workbench and brought back an air freshener and some bottles.

‘I’ll spray some of this new thing I’m testing on it. It should do the trick. Keep it. I’m trying to see if I can sell it somewhere. Make some extra money.’ Leaning into my car from the driver’s seat Shereef scanned the inside, then stopped at my dashboard. With a half-smile he looked at me, shaking his head. I had five half-sucked mints sat in a row like ducks on my dashboard that I was sure calmed the nausea that the stench refuelled, and La Nausée, as Sartre called it, that came to me in waves. They made my car feel clean somehow, even though they were lathered in my slobber. As I threw my cigarette in a barrel by the garage door I turned back to see Shereef with his arms open.

‘We’re going to have our cake someday,’ he said. ‘Ten more minutes and you’re good to go.’

5

I couldn’t pick up passengers for another hour because of RideShare’s break policy (Clause 7, no more than twelve consecutive hours of driving) and because I wanted to make sure I got the evening crowd. I made my way from Shereef’s garage back downtown. Driving through the city with my window down, I was aware of my moods. What I saw was how I felt, but sometimes, what I saw was just ugly.

‘Wait. Wait!’ A woman ran for a bus, propelling her stroller as if she was in a pushcart derby. The bus did not stop for her.

‘Hey, sexy!’ a man hollered at a woman as she walked by. ‘What? Can’t take a compliment?’

‘Do we even have a lighter?’ asked a boy huddled with a group of his friends as they tried to rip open the plastic around what I assumed was their first pack of cigarettes.

Gray concrete box after gray concrete box. Flashy buildings sprouted between apartment blocks where the plumbing was close to exploding and the cladding outside could catch on fire with a single spark. Shit will rain on us someday.

‘You don’t have to go to class today, do you?’ A man who must’ve had grown-up kids held a teenager’s arm as she looked up at him with a twinkle in her eyes. I debated between shouting ‘Pedo!’ or ‘Daddy issues!’ but settled on ‘He’s using you!’ instead, because I didn’t want to hurt her feelings. But by the time I said it they were well past me, and some woman walking by gave me the finger. Driving as many people around as I do has made me a clairvoyant for determining which couples are meant to be together, and which ones should just stop being. Love is blind, but I’m not.

‘Linda, you won’t believe it. I’m getting promoted,’ a man on the sidewalk said into his phone, wearing a suit that was certainly not off the rack. ‘Vernon says it’s about time. I told you, trips to the golf course are part of the job. Drinking late is networking, baby.’

Stopping at traffic lights was better than eavesdropping by a water cooler, and I felt myself calmed by the chaos until I spotted a diaper driven over as if it were roadkill, stuck on the concrete creating a speed bump. I sighed. There was a grime to the city, a spillage so toxic it smothered people that passed by. The air was far from fresh, but there we were, breathing in every bit of this manufactured life and asking for more. We couldn’t get enough. The city thrived on the dreams of the smothered. As always, I thought about Appa.

6

The sun was out. The glass in front of me magnified the heat. When I switched between foot pedals, I felt a twinge run up from my calf. It strung round my hip and up to my arm. The wheel was pulling against me. My wrists hurt, though not as much as they had when I first started driving. My back ached. I wanted a cigarette. I’d massage my body in a hot bath at night, hoping crystals of salt would heal every twinge inside of me. If that’s even a thing. Amma called again. I had ordered her a puzzle, but still needed to buy more word searches, something to distract her. I had already downloaded a bunch of pirated movies and queued them up for her, because when she didn’t have anything to do, she called too often.

‘What is it, Ma? I’m driving.’

‘You didn’t call me back. I need you.’

‘What’s up? You okay?’

‘We don’t have bananas. There are only four teabags and I’ll use three by the time you come home.’

‘You can use one to make at least three cups, you know that already.’

‘I’m tired.’

‘All right, I’ll buy tea. You think you can walk to the shop today? Maybe try and get to the door at least. Get some fresh air at the step. Move your body.’

‘No. Not today. I have to go now. The TV is on. Where are you?’

‘I’m here, Ma. I’m driving.’

I never tell people where exactly I am and I won’t tell you which city I live in either. In our current times, a city is a place, is a space, is the same everywhere minus the design of buildings, the demographics and the weather. Cities have all been structured the same. Right now, a few people have a lot, some are just fine, most are struggling. As long as I’m alive, does it really matter where I am? Besides, if the wrong people know my location, they’d find me, fine me, put me in prison for something that wasn’t my fault. Am I just paranoid? I don’t think so, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Bananas, tea, a paint-by-number of some kittens in a basket, and chocolate almonds. I needed at least twenty-five bucks in cash by the end of the day for my sanity and my mother’s. I couldn’t dig into the funds we had to merely survive. It wasn’t a crime to spend money on things that made us happy, but most times that kind of money just wasn’t there.

I closed my eyes.

The app pinged me. It was okay to drive again.

7

When the stars aligned, driving for RideShare was like driving a confessional. I was an anointed Sister sat on near-ripped upholstery with Nouveau Car scented air freshener for incense, and no velvet drape to protect me. I didn’t always care to hear passengers’ problems, but it occasionally made me feel like a better person to do so. Therapists were expensive and most people these days were atheists. Besides, God doesn’t always show that they’re listening. For the most part, though, driving was simply driving, day after day, night after night. If I had ten passengers in one morning, half of them wouldn’t bother to speak to me, three would be with friends so I was definitely a nobody, and the other two would be anyone’s guess. Soul-spillers, secret blurters, conspiracy theorists gone wild. Sometimes there were those who went on about how I was exploited, my RideShare was the devil of all companies, but they had to use my services just this one time.

Cab drivers are expected to have the inside scoop of every city, town or village they drive in. Us RideShare drivers know the roads, obviously, but most of our passengers don’t trust us, probably because we aren’t registered cab drivers. In the ranks, RideShare drivers were at the bottom, before delivery cyclists of course.

A few hours of mostly waiting had passed, aside from three pings. I was at about $19.40 for the day and that was enraging. I’d normally cancel low-paying rides, but RideShare’s new policy, implemented out of the blue, was that drivers could not cancel more than two back-to-back rides. All of us were just offloading shitty pings to each other in a desperate game of ping-pong.

I stared at myself in my wing mirror while I waited for a Derek (3.4 stars). My teeth were yellowed, but cigarettes and coffee were too delicious for me to care. They made love in my mouth like it was New Year’s Eve and they had no resolutions.

I practiced my smiling, conscious to hide the stains, because if I was lucky my smile would make them hit that tip button (10% of which still went to RideShare). Some days it took a lot out of me but today I was in the mood to pull back those muscles and show off those off-white pearls. I looked possessed. I looked constipated. I looked incredibly desperate. I wiped my mouth.

Derek looked rich. He had a turtleneck on and it was summer. Was he pretentious or pretending to be? Beside him, standing about five foot four in camel flats, was a woman maybe six years younger than him, I’d guess. The two of them had rosy skin, flushed from sangria and maybe a midday shot each.

‘How you doing, friends?’ I smiled, practically ripping my cheeks on either side. I turned so they saw me. My face, my eyes, the things that made me human behind the wheel.

‘You don’t have an accent! You’re the only driver in this city who doesn’t,’ said Derek.

‘I’m sure we had a driver yesterday who didn’t.’

‘You’re too tipsy to remember. You know where you’re going?’

‘Oh, yeah. Don’t worry,’ I said.

‘I’m almost certain the driver we had yesterday didn’t have an accent.’

‘As certain as you were that you wouldn’t talk about our personal matters at lunch today?’ Derek hiccuped loudly.

‘Sorry to interrupt,’ I said. ‘But if you’re going to be sick, I’ve got a bucket in the back.’

‘Sick? It’s fucking one in the afternoon. *Hiccup.*’

‘I can put some Phil Collins on for you. It’ll be “Another Day in Paradise” and whatever’s going on in your stomach will subside. I promise. My ma loves Phil Collins, swears by him.’

‘You just keep your eyes on the road. *Hiccup.*’

‘I brought up one thing. It’s no big deal. So what if they know you talk in your sleep?’

‘Talk in my sleep? You said more than just that. *Hiccup.*’

‘All right, I’m just going to pull over here and grab that bucket. Can’t be too sure about anything these days, right?’

‘No, it’s fine! *Hiccup.*’

‘Because I mentioned that one time you said—’

‘Don’t even *hiccup* start, Marta. Are you sure you know where you’re going?’

I parked my car on the side of the road, knowing that if I stayed there for five hours, RideShare wouldn’t even call to find out if I was dead.

‘Have you ever cleaned the aftermath of projectile vomit in a car? I’m going to get my bucket.’ I reached for my door handle, checking for cyclists.

‘For fuck sakes. We’re going to be *hiccup* late.’

‘It’ll be a second.’

‘How can you be this upset? It was one slip-up.’

‘One slip-up at a work lunch for a merger, Marta. What don’t you fucking get?’

‘So, I won’t get that bucket then?’

‘Fuck!’ Derek shouted, grabbing the passenger seat and shaking it.

‘It’s going to be fine, Derek,’ soothed Marta who honestly should’ve just kept quiet because even I knew he was one of those guys that was a ticking time bomb, as composed as he tried to present himself, hence the turtleneck. He turned to face Marta and held her shoulders square with his hands.

The tire iron was under my seat. If things got heated I knew I could reach down, grab it, turn towards the back, and smack Derek in the head with it. Then I realized the pepper spray would be easier, but I had used pepper spray once in my car and learned that it’s not a good idea in small spaces. I heard one last hiccup, and then Derek screamed in Marta’s face. ‘I can’t stand you sometimes!’

I hit the panic button on the app, thinking he was going to hurt her, but he opened the back door.

‘I’m giving you zero stars,’ he said before storming out of my car like a five-year-old. Marta looked at me and rolled her eyes.

‘I’ve called for help. I can give you a ride somewhere, for free of course,’ I said to her.

‘It’s fine. He’ll get over it. Fucking child. Here.’ She handed me a fifty-dollar bill she had pulled out from her purse and my mouth did this natural thing that could only be called a smile. Marta got out of my backseat, and walked off in the opposite direction of her hot-tempered lover. I hoped she wouldn’t take him back again. She was too far away to hear when I said, ‘Thank you.’

8

Every day I saw how people found ways to get high. Hard drugs, soft drugs, shopping, drinking, sex, fads and online personas, stretching their phones out in front of their faces, immersed in their tiny screens. People did all sorts of things to feel alive. They were big adult babies scavenging for life, for that sensation, you know, the one that makes you feel just right. But if you looked close enough, sat on a park bench alone, leaned against a brick wall in a dirty alleyway, you’d see people who’ve stopped to catch their breath. Between the beats of a racing heart full of fear and anxiety, they nearly choke to death.

Jolene would say we could have it all, and I believed her. She was a paper bag I could breathe into while she stroked my hair saying, ‘Everything will get better. Let me make you a sandwich. With the miche loaf, okay?’ Her mouth tasted like grape jam, her bread worth the $18.

I was on my way to pick up a Daisy (4.2 stars), midtown. En route, I drove past a school that looked similar to the one I had attended. Students as young as five were sat outside the gates holding signs they’d made with crayons, paint and coloured pencils.

WARM YOUR HEARTS, NOT THE PLANET.

Wat’s the point of schoolif the planet is on fire?!!

Frack OFF earthfrackers!

OUR TEACHERS TEARS WILLADD TO THE WATER RISING.

That last sign was my favourite because the A-star pupil had cut out a yellow sports car, pasted their teacher’s face onto it, then marked it over with a frown using a thick black felt-tip pen. The car was sinking in a pool of blue.

Two streets down, while I was waiting at a red traffic signal, three people crossed the road. First was a man with a tight shirt and well-ironed shorts with loafers and no socks in sight. I wondered if his shoes reeked of nacho cheese sauce. A woman with trainers and a blazer and skirt ensemble was close behind him, and then another woman with silver high boots and a pleated dress that had a neon cat puking a bubble of sequins on the front. Someone sewed every single one of those sequins by hand all the way down to the hem of her frock, and my guess was they were still sitting at their sewing machine in a factory with no windows. How much did the products these people lathered and washed off their faces cost and were any animals hurt in the process of production? In their hands were signs that read:

Tech CompaniesDemand the End ofClimate Change.

Tech Companies SayNow or Never.

The three of them stopped at the signal on the pavement to chat. They shared a laugh and then they all walked to their individual cars, lined and parked along the curb.