Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

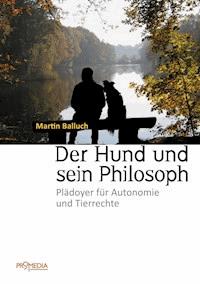

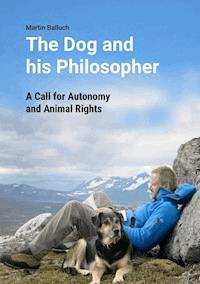

The dog "Kuksi" lives together with his human friend Martin Balluch on an equal footing. Especially on their long excursions into the wild, they can only survive if they communicate, cooperate and help each other. Indeed, Kuksi turns out to be someone, not something, who is acting responsibly and with reason. These experiences, recounted at the beginning of the book, are supported by findings in behavioural science and ethology, detailed in the following chapters. It leads the author, a learnt philosopher, to conclude that his dog friend must be considered as a person with free will, over and above any genetic drive and operant conditioning. Usually, the ethics of animal welfare and even animal rights are supported by arguments based on the capacity to suffer. In his book "The Dog and His Philosopher", the author Martin Balluch uses a different approach. He observes that even if animals are considered capable of suffering, as in animal welfare laws, they are not considered as self-aware beings with their own view of the world, wanting to run their lives in their own way. In other words, beings with their own will to autonomy. Using his experiences with his dog friend Kuksi, he claims that dogs, and hence other sufficiently similar animals, must be seen as beings with reason in the sense of Immanuel Kant, a central philosopher of the enlightenment, on whose work the idea of fundamental human rights as a means to protecting human freedom is based. Reformulating Kant with an evolutionary understanding of reason, the author concludes that nonhuman animals are also capable of what Kant considers freedom and autonomy, and hence must be protected by rights too.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 467

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Kuksi, Stella and Hiasl

First limited edition

Vienna 2017

translated from German

by Paula Stibbe

cover photo

by Daniela Deml

layout

by Franz Gratzer

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Prologue

Introduction

Chapter 1: Kuksi and me

Looking back

Our life together

Kuksi and wild animals

Five days without a rucksack

Weeks away from civilization

Kuksi in the city

In Winter

Chapter 2: Kuksi from a scientific perspective

Kuksi's intentions

Emotions and empathy

Thinking without language

Communication

Understanding

On morals and rules

Chapter 3: Hiasl's story

From the jungle to Austria

Meeting Hiasl

Ban on experimentation and rehabilitation

Trial to get a trustee for Hiasl

Chapter 4: On dogs and chimpanzees

Dogs, as seen by biology

The brain of a dog

A dog's 'social toolkit'

Canine cognition

Chimpanzees

Chapter 5: The divide between animals and humans

Humans and animals before the Enlightenment

Humans and animals as seen in the Enlightenment

From speciesism to racism

No rights for animals

Chapter 6: Consciousness and autonomy

Close relations

What is consciousness?

Instinct, conditioning and autonomy

Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem

Summary

Chapter 7: Kant revisited

Anthropocentrism or Pathocentrism

Utilitarianism

Animal rights and human rights

Kuksi in the realm of ends

Kuksi also an end in himself

Summary

Chapter 8: A multi-species society

Veganism: Health

Veganism: too much to ask for?

Basic rights

Kuksi – autonomy and civil rights

Hiasl – having a legal guardian and being a non-human person

Wild animals – self organisation

Summary

Epilogue

References

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks are due first of all to my dearest Kuksi for his friendship and love, and for his endless patience while I was writing this book. I'm looking forward to many weeks and months with you in the wild!

I also want to say a big thank you to Estella Kubek, who really supported and encouraged me, many thanks for the valuable comments on the different chapters.

Thanks also to Paula Stibbe, who not only introduced me to Hiasl and commented on his chapter, but also translated my book into English.

Thanks to Rosi and Hiasl for the times we have spent together and for their friendship – even though they have more than enough reason to hate people.

I also want to say a big thank you to Birgit Deutsch and the veterinary practice Hirschstetten in Vienna, who helped us so much through the dramatic months of chemotherapy.

Thank you to Eberhart Theuer and Stefan Traxler for the help in our joint fight for Hiasl's guardianship trial, also to Eva-Maria Maier, Stefan Hammer, Volker Sommer and Signe Preuschoft for their excellent expert witness statements.

My thanks are also due to the organisation VGT (Association against Animal Factories) as my employer for making it possible for me to write this book.

Thank you to Kurt Kotrschal, who showed me the Wolf Science Center and who, through his talks, inspired me to write this book.

Many thanks to all scientists, who are interested in non-invasive research into dogs and chimpanzees, and in particular to those, who spend their time in the jungle. It is not a given that they should pass their valuable knowledge on.

And last but by no means least, I want to thank all those who stand up for animals and animal protection, or who have made the switch to a plant-based diet. You give me hope that we do have it in us to fundamentally rethink our position regarding animals and that we one day will truly achieve a multispecies society!

PROLOGUE

In 2004, I wrote my doctoral thesis in philosophy on animal rights at the University of Vienna. It was very important to me to bring this subject into the academic world in a serious and scientific way. In those days, there wasn't much to hear on this topic at university level in Austria. A lot has happened since then however. In the mean time, human-animal studies has established itself and animal rights is no longer a foreign concept in philosophy or in biology.

In 2008 a group of masked people broke into my flat during the night. They held me at gun point in my bed with their weapons at my head and shone a flashlight in my face. It was the police. I was suspected of being the head of a criminal organization planning an animal rights revolution. For 105 days, I disappeared into a prison. My doctoral thesis, which by that time had been published as a book (Balluch 2005), was seized during the house search. Eventually, it was because of the thesis that I was charged as being a leading thinker for criminal animal activists, besides 29 more charges. In 2010/2011, I had to endure a gruesome 14 month trial.

In the end I was found not-guilty on all charges. Long after this verdict, I was given back the last of my confiscated possessions, one of which was my thesis. The ideas in my thesis also played a role for the Head of the University of Vienna to decide to ban me speaking at the university. When I asked why, I was told that I was deemed a security risk. If I gave a talk, it could not be guaranteed that my audience wouldn't rise up and go on the rampage.

What kind of explosive ideas must I have had in order for them to bring about such a reaction? Or do those in positions of power in our society have so much to lose, were we to start taking animals seriously and respect their autonomy? When I left prison, I decided to take on a dog from a shelter again. Being stuck in a cell for so long made me aware of how awful it is to be robbed of your freedom for no reason. I found my new friend Kuksi in the animal sanctuary 'Tierparadies Schabenreith' in Upper Austria. Two months before, he had been dumped by a motorway service station. We both had a new life to begin.

Eight years have since gone by. We have grown close and inseparable. Our friendship inspired me to write this book. In everyday life it is so self-evident that Kuksi thinks and feels and behaves autonomously. How could anyone dispute it?

As a scientist, I have collected many facts in addition to our personal experiences, in order to present the case for Kuksi demanding autonomy in our society. A lecturer claimed in a series of talks on animal ethics held at the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna in 2008 that Immanuel Kant was right in saying that animals are only things. Kant is influential to this day, not the least because the Austrian civil law code is based on his thinking. Humans are persons, animals are things, this is the bottom line. This book is a head-on confrontation with Kant's teachings. It uses his form of reasoning to demand rights for animals and their personhood status. I think that, with the knowledge we now have about animals, this conclusion is inescapable.

I hope that this book will make a lasting impact, without it resulting in masked police once again breaking down my front door in the middle of the night!

Martin Balluch, July 2016

INTRODUCTION

I love nature. And by that, I don't just mean I like walking through city parks, reading books about nature reserves or tramping along well worn footpaths up to classic mountain peaks. No, I cannot live without going into the wild as often as possible. I search out untouched forests, where there are no traces of humans to see. I go off paths and avoid mountain cabins. I travel to the Arctic and Northern Scandinavia or I spend weeks in the Southern Carpathian mountains or at home in the Eastern Austrian Alps. The internal urge to be in nature is so strong that I organize my career and social life such that I can spend around 100 days a year in the forests, mountains, tundra and taiga. It can hardly be called a visit, it's more like a home coming. For me, every day that is not spent in nature is a lost day.

Actually, I would have thought that this longing is the most normal thing in the world for a primate such as myself. For a being made and evolutionarily adapted for climbing trees, it's only to be expected that I have a longing to want to do this. And, that's exactly how it is. Once, I was allowed to work for a number of weeks at the European Nuclear Research laboratory CERN in Geneva. The first thing I did when I arrived there was to climb a tree in the campus grounds. The scientists showing me around were completely baffled. But from my point of view, I couldn't understand how anyone could live without climbing trees, smelling their bark, lying in their branches and feeling their structure with your hands. I cannot, as I found out during my time in prison. I was wrongly locked up for 105 days – as later confirmed by the court. One hundred and five days with concrete and fluorescent lighting, not a single green plant or any trees in the prison yard. This was the worst time of my life.

For the people in my social surroundings at least, this longing of mine lies outside the norm. I'll never be able to understand why, for most other people, nature is a world that they hardly seem to miss. I was able to observe this in the people I shared different cells with during my stay in prison. Hardly anyone suffered from not having access to nature in the way I did. There, the wild had mainly negative connotations, as something cold, inhospitable, unpleasant, arduous, wet and non-protective. The warm cell was seen in contrast as a comparatively pleasant place. The one time, during the 105 days that I was allowed to have 3 books from the prison library, all of which were about being in the wild, my cell mate told me, in no uncertain terms, that he would rather be here, locked up in this cell, than at the North Pole in Franz Josef Land in a tiny cabin, like the people in the book. For me, it was totally the other way round.

This nature deficit disorder (Louv 2008) also accompanies me outside the prison walls, all the time and everywhere I go. Many people are not at all drawn into nature. They are content with a book with impressive pictures or a nature film. Others like going hiking, but only on marked paths where they need not exert themselves and only walk from the comfort of one cabin to the next. And then there are those who are there not as tourists but as sports enthusiasts. They seem to see the mountains more as sports equipment than as their natural habitat. Tours are only interesting when they are on difficult summits, over glaciers, frozen waterfalls or vertical rock walls. Simply wandering through the forest for days on end, through thicket and without a path, in a tent rather than a cabin, this is a program for the minority.

The main reason for this is probably comfort. If you stand in the pouring rain, you really learn to value a roof over your head. When insects sting and bite, a window to shut nature out seems ideal. When there's no source of water in the heat, a tap is the best invention of the last 1000 years. And, when you crawl though thicket, you dream of a well trodden path. But, this is too simplistic. When you have all these objects of civilization, you no longer value them. No wonder depression is rife in luxurious surroundings.

I want to feel my body. I want to get wet in the rain, to get scratched by thicket and pushed to my limits by thirst and hunger. Getting stung and bitten by insects is something I could do without, but it's a price I happily pay to be out in the wild. I am really in my element when I spend a night in the rain, without a tent or a sleeping bag, on the forest floor. Or in a snow storm, digging a sleeping hole. Only then do I really feel alive, everything else seems like a fantasy, like a soap opera on TV.

This approach to nature opened up a new perspective on animals for me. It's no wonder that people see animals in the forest as fundamentally different to themselves when viewed from their sofa. Here culture, there nature. The humans inside couldn't even survive without technical help, whereas the animals out there seem to be made for survival. We can see how quickly the impression of an unbridgeable gulf, that leads to the justification of different treatment, is made. When I'm lying on the forest floor in the rain, I meet the fox at the same level. He and I have the same problems, and these problems are totally different ones to those occupying the creatures on the sofa, in front of the TV and behind their double glazed windows. We are hungry, the others have to take care that they don't get too fat. We are fighting off the cold, the others have the problem that their heating is destroying the climate. We are thinking about how we will get through the next few hours, the others are boring themselves to death and searching desperately for some form of entertainment that will kill time. It's not surprising then, that from my perspective, the difference between humans and animals is totally blurred.

I am a wild animal. If I had to decide, which side I was on, I would choose being an animal among animals in the forest. And that is a deep inner feeling, not an intellectually thought through world view, not a rational rejection of the destruction and violence in society, and not a pushing away of my responsibility for what humans have done to the natural world. The last point is what always brings me back to the urban environment. The remaining areas of primeval forest and untouched nature have become so small that I couldn't hide there and pretend that the last 20,000 years of human history hadn't taken place.

Those people, like me, that search for the wild, mostly think like the adventurer and prolific author Nicolas Vanier (e.g. Vanier 2006). He enthuses not only about hunters with their metal traps killing wild animals for their fur, but also about his 2 year old daughter, standing up to her ankles in the blood of a shot moose, showing no sign of sadness or empathy. According to Vanier, empathy is for weaklings in civilization. Out in the wild, other laws prevail; it's kill or be killed and empathy just gets in the way, a maladaptation to the existing reality. It's strange though, that he doesn't extend this view to humans in the wild. Either they too are wild animals, which would justify their violence towards other animals, but also make it permissible to kill the next hiker that comes along in oder to get his or her supplies, or humans exist outside the laws of the wild as seen by Vanier, meaning that their basic rights must be respected but, also that the idea of might is right cannot be used to justify the bloody trail left through nature. It has to be one or the other.

For humans, wilderness as a place of raw violence therefore has a political function. Best known is probably the way Thomas Hobbes emphasizes the apparent awfulness of the natural state in "Behemoth" which depicts a fight of everyone against each other that can only be overcome by having a civilised state. In his book "The Selfish Gene" (Dawkins 1976), Richard Dawkins also writes of "the survival of the fittest" and of "nature red in tooth and claw". Immanuel Kant even saw it as a moral obligation for humans to let go of nature and to organise a state governed by laws which are executed by police in order to achieve freedom. So, the wild supposedly is a continuous fight for survival, cruel, brutal and short-lived. The Giordano Bruno Foundation also speaks of how gruesome it is in nature, making it necessary for civilisation to intervene. Today, we notice this attitude in the way domestic animals are locked away on factory farms and how companion animals like dogs, are prohibited in more and more public places. The need for cleanliness, physically as well as psychologically, includes a distancing from animals, a separation of civilisation from nature.

My experience of nature is totally different. In the countless days I have spent outside, there were comparably very few instances of aggression and suffering that I have seen. How often have I observed herds of chamois peacefully grazing, ibex kids happily playing, bear families roaming through the under-growth and foxes lying in the sunshine, badgers rolling on the ground and ravens soaring through the air in their courtship flight? No violence, only the sheer joy of being alive, having social contact, trust and cooperation. Wild animals' daily activities seem to be satisfying, symbiotic and collaborative. Their social life is almost completely peaceful, the fights between ibex or between stags are ritualised and the ones that I have witnessed have all ended without injury. It becomes clear: most wild animals are most of the time really happy and content.

Jonathan Balcombe discusses this point in his thoroughly readable book "Second Nature" (Balcombe 2010). He states that the aggression depicted in nature documentaries, which, in turn, form public opinion, is totally exaggerated. They focus on bloody scenes because this is what grabs people's attention. In reality though, the number of carnivores in each ecosystem is only a tiny percentage of the number of their potential victims. This means that such bloody scenes are relatively rare and when they do happen, the victims are very young, sick or old animals. Fit adults can feel more confident and can generally outrun their carnivorous opponents. Many animals in the wild live to a ripe old age; there are 32 year old ice bears and narwhal whales who have reached 115.

Social animals often care intensely for each other. In many instances it has been observed that ill and disabled animals survive due to the care of their family or social group. De Waal (2013) describes how a rhesus monkey girl with down syndrome is not only tolerated by the wild living group, but is also fed and cared for. In the Japanese Alps, a severely physically disabled macaque, who was hardly able to walk, never mind climb, lived a long life and brought up 5 children. It is inconceivable that she could have done this without help from those around her. Population control happens through infertility due to scarcity of food or through a resorption of the fetus into the mother's body far more often than it does through violence. And generally speaking, parasites have developed through evolution to live symbiotically with their host as otherwise, the death of their host would also mean their own death. Due to the fact that many animals, such as the peacock with his huge tail feathers, have developed extravagances, it can be assumed that they generally find survival easy. Wild animals are not continuously fighting for their survival, says Balcombe, they have lots of free time for playing and socialising. Peaceful cooperation rather than violence determines events.

That's how I see it too. My attitude towards other animals in the wild is determined by empathy and that is not a cultural achievement, rather a natural, widely occurring predisposition. Once, as a mountain guide, I was hiking with a paying guest over a high plane after successfully ascending a climbing route. As we came over a hill, we met a herd of Chamois who, startled by us, ran from each other in all directions. We quickly moved behind some rocks so as not to disturb them further. From there, we were able to watch the chamois. In the upset, one of the children had been separated from his or her mother. It ran, calling from one chamois to another, but to no avail. The mother was on the other side of a steep slope and was also desperately calling out for her child. My companion and I both felt a huge amount of spontaneous empathy for the mother and child and we were greatly relieved when the two found each other again. I would consider not feeling similar empathy in such a situation as pathological. What kind of person could be left cold during this observation?

There is also another side to my life, mathematics and philosophy. I worked for 12 years as a university assistant for mathematical physics at the universities in Vienna, Heidelberg and Cambridge. My PhD thesis in philosophy was also published as a book (Balluch 2005). It presents an analysis of animal ethics using mathematics and is based on findings from the natural sciences. This abstract intellectual approach to the world compliments my direct experience of nature.

As the central philosopher of the Enlightenment in the German speaking world at least, Immanuel Kant is dominating the discussion over ethics to this day. Civil law, which governs the way we live with each other in society and our relationship to animals, is based on his thinking. He earned his well-deserved place in history for developing or, if you like, discovering metaphysics, which is independent of religious assumptions. It must be said though, that he had absolutely no contact to nature, he never left his home town Königsberg. I would make the claim that having direct experience of nature and wilderness provides impulses that can help overcome Kant's artificial, cold human-animal dichotomy. For Kant, nature was something to be transcended by humans in order to find one's self. I would urge us to rediscover the wild animal within us and not to fear it. It is not ruled by aggression, it is ruled by cooperation and empathy.

For Kant, human freedom was at the centre of his Metaphysics of Morals. As a result, moral behaviour in the West prioritises respecting the autonomy of others in as far as is possible. Kant's ethical conception is therefore not oriented around minimising human suffering, in contrast to the general attitude in animal welfare, which is to minimise animal suffering. The autonomous decision is to be respected even when this means increased suffering. And stealing from or murdering a person in order to help many others is in principle excluded, even if that was to serve the overall good. This morality is anchored firmly in the law as basic rights, which protect humans from a utilitarian approach to our dealings with each other. Basic rights here refers to the right to life, liberty and bodily integrity. They make the stage on which autonomy can be lived out. Autonomy is also the central term in my experience of nature. On fur farms, wild animals such as mink and foxes are confined in cages. They are given enough food and water and are protected from other predators. They don't need to go hunting and, if they wanted to, they could just lie around content in their cages. But they break out of their cages if there is a chance. They try everything to get free. They bite through the cage or make a dash for it when the cage is opened. A population of American mink, originally from a fur farm, has lived in an area of Lower Austria called the Waldviertel for generations. There is also a similar case in England.

In their escape, fur animals are voting with their feet in favour of autonomy over minimising suffering as their prime motivation. They would rather have the stress of a life in the wild, would rather starve, be chased and exposed to the elements than rot in a barren cage. I can fully understand this. I also prefer the hardship and danger of the wild to lying on the sofa. Although, it must be said that the life of a human in civilization cannot be compared to the life of an animal on a fur farm. But, I prefer climbing on a rock face with all the inherent risks, to staying protected indoors. Intuitively, autonomy is more important to me than minimising suffering.

And I do not stand alone. The women's movement, especially around 1900 and from the 1950s to the 1990s also demanded autonomy. Up until that time, women were maybe cared for by their husbands and didn't have to work, but they weren't allowed to make decisions about their own lives or about their country's politics. The demand was for their own autonomy, but in return, to also make their own living and assert themselves independently in society. It maybe hard work to stand on your own two feet, but that is the prerequisite for freedom and autonomy. And today it is acknowledged that women are rightfully entitled to these.

Over decades, dogs have accompanied me in my escapades in the wild. I sensed the same passion and the same fire in them as I did in myself. The relationship to my dog friends was characterised in the wild by the fact that we were on an equal footing. Two autonomous creatures, who look out for each other. In many aspects dogs are more capable in the wild than humans. If they were given enough freedom in their younger years so that their personality could unfold, they would not need us to survive a life in the wild. They could take care of themselves and even turn the tables and help and advise us. That is why I have chosen to begin this book with my tours through the Arctic with my dog friend, in order to get closer to a new definition of the human-animal relationship.

Autonomy in dogs? For many people this sounds like a contradiction. In the city environment a dog is led on the lead, made to wear a muzzle and follow commands. Dogs must be controlled, they are viewed as potentially dangerous. In particular, dogs cannot be trusted on the street, the traffic rules would be too much for their limited intelligence. Strange then that so many animals like foxes, martens and even badgers live in the suburbs without being constantly run over. I would urge anyone with these views and who lives with a dog to go together into the wild. Go for a week with a tent where there are no traces of other humans and you will change your mind. Dogs are in truth amazingly independent and if they are well socialised, very cooperative and peaceful. It is not necessary to control them or to make them submit to you as the pack leader. Dogs are social in a comparable way to humans. They want to live in an egalitarian group and make their own decisions whilst still being happy to go along with the decision of a more experienced group member. In any case, this is how packs of wolves and human families function.

For people who are totally disconnected from nature and animals, dogs can seem threatening, like ticking time bombs. In the absence of language, it seems that it is impossible to find out what they are thinking. And apart from that, animals supposedly have no morals and because of that, they are unpredictable. That's why the view is prevalent that it would be better if they were excluded from human society as much as possible. In this way, dogs are reduced in people's perception to instinct driven robots or to behavioural stimulus-response machines. Dogs are seen as capable of any violent act at any time.

In this case too, I would recommend a trip into the wild, to get in touch with reality. Just as humans do not only behave rationally and sensibly, nor are dogs totally irrational or stupid. When I am going through the wild with my dog friend, my voice quickly dies down in my head and I think without talking –just like a dog. Decisions, such as, which direction to take, where we should make our camp or which way is safer through the rocks, are all made without words. We communicate with each other constantly and get along extremely well. The canine soul is not a foreign world for me, I can usually clearly understand and empathise with how he is feeling and the other way round too. We trust each other totally. In the wild it becomes clear to us that we are pretty much the same.

With this taken as a starting point, one comes to a totally different world view. The Enlightenment put humans in the centre, and encompassing all humans in one common family is without doubt a great step forward. Nevertheless, this commonality has been achieved at the cost of distancing ourselves from animals, which has been to their great detriment. We must ask ourselves whether this 'we' which refers to all humans cannot be extended, whether next to multicultural societies it would not be possible to have multi species societies as an option for the future, raising the quality of life for all concerned. This book seeks to explore that question.

CHAPTER 1: KUKSI AND ME

We have covered a lot of ground already today, walking north of the tree line in the Scandinavian tundra. Now we have stopped for a long rest, we lie down on the short grass. It is peaceful and relaxing, no bad weather in sight and pleasantly cool. Suddenly the sun comes out from behind a cloud and burns down on us. This direct heat wakes me and I lift my head. Kuksi is lying next to me and does exactly the same. Where is the next shade, I think to myself, and I see a large boulder about 20 metres away. So, I stand up and Kuksi stands up next to me at practically the same time. I walk directly towards the boulder and Kuksi, as if following a command, walks by my side. In the shade I once again lie down and Kuksi does the same. Kuksi is my dog friend. We have been walking together now through the wilderness for days.

The heat had become a problem. I thought about a solution and found one in the shade of the boulder. For Kuksi, it wasn't just similar, he solved the problem just as quickly and in the same way. Sun and shade may be simple things, but they make a big difference. In nature, I see time and time again how similar Kuksi and I react to things. For me, it's self evident that he thinks and then acts. Neither of us need language for this.

Late in the evening I put the tent up. Kuksi wanders off, as he is given to do when we camp out. When I'm finished I see him sitting in the midnight sun on top of a hill a few hundred metres away, looking out at the landscape. He seems to being enjoying the view so I join him on the hill and sit down next to him. From here it's possible to see far into the distance over the seemingly endless flat planes. There are lakes everywhere reflecting the low lying purplered clouds, typical of the Arctic. There is no sign of civilisation. The ground here is frozen for most of the year, but now in summer, the higher planes thaw a little and as a result, the ground is very wet. Here and there, we can see small areas of birch forest, sparsely populated with around 2 metre high bent trees.

The peace and stillness of this place makes a strong impression on us. It's as if time is standing still. Kuksi nuzzles me with his wet nose and I stroke his head. We belong together, nothing can separate us. He lays his head on my thigh and being close to him gives me the safe feeling that I'm not alone in this world. I think of all those things the two of us have experienced together!

Looking back

I had lived with dogs over two decades before I met Kuksi. My first dog friend was Hassan, a raven-black German Shepherd. We got on like a house on fire. When he was young I was made to go to obedience classes with him. At that time, everyone thought that dogs instinctively wanted to get the upper hand over their care takers and it was therefore necessary to dominate them into submission. I had to walk with him on a short lead and constantly yell 'sit!', and 'heel!' at him. If he ignored me I had to yank on his lead. With my sixteen years, this seemed absolutely absurd. Our everyday life with each other was totally different.

Although I found the training repugnant and rejected this kind of authority over myself at home and school as well, I stuck with it in the obedience classes. Hassan tolerated it for a while, but then he sprang up and pulled on my hair. I looked him in the eyes and saw there the question why I was behaving so strangely. I had to admit, he was right. That was the last time I tried to dominate a dog.

Later Max came to live with me. He was a mixed-breed from the city animal shelter. Apparently, he had bitten two kennel assistants there, but with my partner and myself he developed into a completely socially competent and thoroughly lovable dog. He reacted aggressively towards shouting and threatening gestures. Obviously he had had some difficult experiences in the past, but as long as people were friendly to him, he was an angel. He died in the summer of 2007 at the age of thirteen and a half from a stomach torsion. After an emergency operation, he struggled on for eight days, but his body no longer had the strength to regenerate. He finally slipped into a coma and didn't wake up again.

As sad as his death was for me, I am nevertheless relieved that he didn't have to go through the events which unfolded shortly after. Without us knowing it, the police had formed a special commission against the animal movement. This commission ordered on 21st May 2007 an early morning raid on twenty-three addresses throughout Austria. One of those addresses was my home. Masked and armed commandos broke down the door, stormed in and forced the frightened naked people at gun point from their beds. If Max had still been alive, they probably would have shot him. He wouldn't have stayed calm in such a situation. He most likely would have attacked the people screaming at him and threatening him. And even if he had have survived this attack, we would have been separated for 105 days as I was brought into pretrial custody directly after the raid.

After my release I was acutely aware just how awful it is to be wrongfully locked up. So, I wanted to help another being get out of innocent incarceration. At the Schabenreith animal sanctuary in Upper Austria I met five dogs who had just come from a shelter in a nearby town. One of them had been given the name Habakuk (the sanctuary is well known for the eccentric names given to its residents). Habakuk was just ten months old, a non-definable mixed-breed with definitely some German shepherd and according to the vet who treated him, some Rottweiler in his genes. Most of his coat is black, but his belly in contrast is a very light brown, the colour of 'toast' as a guard at the regional court later pointed out. Someone had tied him up at a motorway rest station and left him there. He looked so sweet with his hanging ears that I fell for him on the spot.

A friend and myself took the five dogs on a test walk. Shortly after that I went to fetch Kuksi, the name I started to use, and took him on a hike lasting several days in the nearby Waldviertel region. We were four people and five dogs and we hiked for nearly a whole week through woods and meadows and past countless lakes. Kuksi and I got on from the word go. He watched my movements closely and mostly stayed by my side. Strangely, he didn't want to swim then. Since then, he has become an enthusiastic swimmer and loves being in water. We often swim for long stretches at a time together now. We have even jumped through crashing waves together in the North Sea. When we took a rest on our hike, Kuksi laid his head trustingly on my lap for the first time. I had fallen in love.

Kuksi soon came to live with me and to celebrate we went at the beginning of November for five days through the Hochschwab mountain range in North Styria, from west to east. He was, of course, very alert and interested in everything. He followed every scent and I had a job to stop him from hunting. He was after all, still a child and inexperienced. We spent our second night by the Teufelssee, a lake hidden by forest and some 1,100 metres above sea level. The temperature was below zero. I was in a sleeping bag and Kuksi lay next to me on the ground. Until then I had only been on tours with longhaired dogs and no amount of cold weather bothered them, but Kuksi war shorthaired and not used to being in the cold. He was freezing, so I got him into the sleeping bag with me.

Kuksi has hardened up after our many years of tours and now, like me, he is very cold resistant. Last winter, for example, we climbed high over the tree line through rocks and ice in a snow storm for four hours at -15 °C. His coat was full of icicles, neither of us were particularly warm, but we still both loved the tour.

Because Kuksi was still very young, I asked myself if some kind of training might be necessary. Classes based on dominance were, of course, not an option, but I let myself be persuaded to attend classes using a non-violent training method. We were told that we should always have a bag of treats to hand and every time the dog did something we approved of, he should get a treat as positive reinforcement. In contrast, we should simply ignore any behaviour we deemed undesirable. This approach is based on conditioning which has its roots in behaviourism. It reduces a dog's behaviour to a stimulus-response action. Commands should be as unemotional as possible in order to be able to make them sound the same each time they are given. Hugging the dog is not allowed as this will cause him stress and if he is stressed, he cannot be conditioned. Throwing sticks is also forbidden as this too leads to stress.

These classes I also stopped going to after three lessons. Decades of living together with dogs made it seem completely weird not to communicate emotionally and instead to condition him through brainwashing so that I could shape his personality. I see my role in living together with a young dog far more in helping him to develop his own personality. He should experience as much as possible and act independently in order to become confident so that he can solve the problems that life will throw at him himself. With people, this is called a non-directive teaching.

When I was young, behaviourism was the dominant model applied to human education. My mother was taught that children who cry should be sent to bed and left to cry with the door closed. In this way, they would get used to not crying. Today we learn in dog training classes to ignore a dog who barks. Both these responses seem totally inhumane to me. A child cries and a dog barks when they want to let you know that they have a problem. They need our attention, and they deserve it too. We are after all, their social partners.

Kuksi has never been conditioned, he has also never been punished. And despite that, he still comes to me when I call him, he doesn't run off and he sticks to our social rules. Non-directive education in no way means neglecting dogs or children, on the contrary, if I cannot give them orders then I need to engage far more with them on an equal footing. If I call Kuksi, then he comes, unless he has other important things to deal with. What's relevant to him is that he has the feeling that what I ask of him makes sense. He ignores requests that are not made for a good reason, and he is right in doing that. He is no longer a child.

The idea that a dog (or a child) would follow my rules and orders out of fear of being punished horrifies me. What kind of relationship would that be? How can there be trust when there is fear? So, imposing rules by using the threat of punishment is out of the question for me. Nevertheless, I can of course set boundaries, I can say that I dislike this or that. A dog learns the social rules for living together by noticing the feelings that his social partner shows. That's why it's especially important to express these feelings, and not only when you're feeling happy and laughing, but also when you feel hurt or angry. Dogs are not only interested in what we do, but also and in particular, in how we feel. Their ability to develop an understanding for the right and wrong way to behave in terms of living together with others is dependent on this.

That is how Kuksi has developed into a very competent social being. It is almost impossible to get into a disagreement with him. And, that's not only true for the two of us, but also for his contact to other dogs. In the city we always walk around without him being on the lead. Ninety percent of the people with dogs we see coming towards us pull their dogs over to the other side of the street as if a fight to the death might break out any moment. The truth is that Kuksi has never got into a serious fight with any dog. Practically all his encounters with other dogs are peaceful, and on those exceptional occasions there is a little bit of growling, the hairs on his back stand up and the two dogs go their separate ways without injury. I am convinced that being on the lead causes unnecessary stress between dogs.

When I first collected Kuksi with the car from the sanctuary, he got travel sick and vomited in the first curve. This is also often the case with children. Over time, when they get used to being in the car it gets better. It's exactly the same with dogs. These days, I can drive with Kuksi 3,700 km, as far as North Sweden, and he's not sick once. On the contrary, he follows the road and what's happening outside the car intently. When a curve comes up, he leans into it in anticipation of the centrifugal force, proving that he knows exactly what a road is and that the car travels along it.

We often visit one region of the mountains in Eastern Austria, you could say it's our stomping ground. On the way there, perhaps about 15 minutes before we arrive, Kuksi starts to get excited and can no longer contain his joyful anticipation. He can obviously tell where we are by looking out of the window. That's impressive, because at this point, we are still 20 km away from our destination. He is capable, just with his eyes, of recognising features in the landscape that he has in his memory and this helps him know where he is. Also in this regard, he is hardly different from us humans.

Our life together

For living together we have worked out joint rules that we voluntarily keep to. Kuksi brought in the rule that it's impolite of me not to give him some of my food if I'm eating and he hasn't got anything. From his point of view, food has to be shared out between us. However, he often misjudges the situation and, not realising that he eats his much faster than me, he can become cross and frustrated thinking that I had more food than him. Never mind that I have three times the body mass to feed. Still, this fact is also not considered when it comes to sharing food among people. If there is only a limited amount of food at hand, it is shared out equally, a 55 kg woman has the same as a 110 kg man. Apparently, that's how Kuksi sees it too.

Many people think that dogs just devour whatever food comes their way. That's just not the case. In my experience, they usually get obsessed with food when they don't have anything to do and feel bored. While I was in prison I saw that food was the celebrated highlight of the day for my cell mates. This isn't surprising if you don't have much to do.

Kuksi is definitely more interested in food than any other dog I have lived with, but, he's still a picky eater. For example, he only eats fruit in any significant amounts when we are walking through the wilderness for days. His appetite for vegetables is limited to a few bites, with the exception of broccoli and peas – these he obviously likes a lot. He rarely says no to tofu, seitan (wheat gluten) or meat. If he finds a carcass on one of our tours and eats until he's full, he turns down any offer of food for about the next 24 hours.

Another rule that Kuksi has introduced concerns the muzzle. Under normal circumstances, I never use it. However, it is required when traveling by public transport in Vienna, and they often send inspectors around to check. So, in this case Kuksi wears it when we go by underground. He lets me put it on without making any fuss and in the underground he remains stoically calm, but as soon as we are out, he stands still and demands that I take the muzzle off. If I don't respond immediately, he rams his nose painfully into my leg until I react. For that reason, I have great respect for this rule.

Another one of our rules is that he shouldn't hunt any animals. As he obviously has some genes from dogs bred for hunting in him, you would expect this rule to be difficult for him, but it's not at all. He never hunts. Just recently we saw a female deer and Kuksi, not on the lead, ran about 20 metres towards her, sending her running off in fright. Kuksi sniffed around a bit and then came back of his own accord without me needing to say a word. The deer stopped a short distance away and started grazing again and Kuksi ignored her completely.

Once, when we came into a garden, we were surprised to see two tame rabbits running around. Kuksi sped off in their direction and I screamed in panic for him to stop, imagining a gory scene in my mind's eye, but, nothing happened. The rabbits jumped about, startled in all directions and Kuksi just gazed at them and sniffed about a bit, leaving them perfectly intact.

In the beginning, Kuksi did kill animals. Once he killed a mouse and during a lemming year in Scandinavia, he killed several of these rodents. I expressed my displeasure and despair and now, it seems to be more important for him not to hurt my feelings than to live out a passion for hunting, which was never a strong part of his character in the first place.

We communicate with each other emotionally via tone of voice as well as body language. I experienced how well this works when he was still young and we were in the mountains. We were walking on a high plane along a rock face that plummeted into a valley not 5 metres beside us. The edge was sporadically coved by snow drifts and Kuksi wandered out onto this snow without a care in the world. These snow ledges can break off, especially in spring, and have sent many a person to their death, including the extreme mountaineer Hermann Buhl. I screamed at Kuksi in horror and he turned around at lightening speed.

There was a similar situation shortly after, where a young man with very little mountain experience also wanted to venture out on such a snow drift. As I shouted at him in the same way, he turned, shocked and just like Kuksi moved immediately away. When I asked him about it, he said he hadn't understood a word I had shouted because of the wind, but the sheer panic in my tone of voice was warning enough and as he assumed I had mountain experience, he had trusted me. I suspect it was the same with Kuksi, even when he couldn't understand the exact words, the tone of my voice was enough to warn him that the threat of danger was present and because he knew me as someone with mountain experience and not someone who shouted unnecessarily, it was worth following my advice.

That is the key to communication between us. Just as I can interpret from his behaviour and the noises he makes how he is feeling, he also can read how I am. I don't need to behave as a dog would and he doesn't need to act like a human. Being close allows this understanding. Of course, there are some words that Kuksi literally understands, for example, 'sausage', 'stick' or 'sniffing game', but on the whole, he reacts to my tone of voice and body language.

This not only has the advantage that you can express gradual variation that's not so easy with spoken words, but also, body language is more authentic. If I see a person shaking with fear and they tell me they are not frightened, then I know which message to take seriously.

Of course, we argue sometimes. Once, Kuksi trod on a drawing pin and cried out. I came over and looked at his paw. As I went to remove the offending object, Kuksi snarled and snapped at me. He didn't hurt me but I was shocked. Kuksi too. "Are you mad?" I said to him, upset. I quickly calmed down, as it was clear that he was in pain and frightened, so I spoke to him softly, turned him gently and slowly reached towards the drawing pin. Then in one swift movement, I pulled the pin out. Kuksi yowled, but then came and pushed me with his nose and licked my hand, a clear sign that he wanted to make things good between us.

I have also shouted at him once or twice, for no good reason. I was angry about something completely different. On these occasions, he ignored me for several hours, giving me the cold shoulder. He also does this when I need to leave him with someone else because I have to go to a conference or somewhere I cannot take him. When I pick him up afterwards, instead of a warm greeting, he snaps his teeth at the air and ignores me. I try to make it up to him and apologise by dropping on all fours and shoving him with my nose. I know he has forgiven me when he presses his head against me or licks my hand. Then we are once again friends.

Kuksi has an understanding for my climbing passion. When we go to a rock face or a climbing route, I tell him that I'm going and he stays put, without being on the lead, all alone in the middle of nowhere. For a social creature, being alone is very threatening, but not for Kuksi, at least not in this situation. And that's why I can be sure that he understands exactly what's going on. When possible, he runs around the rock face, coming up the other side to greet me at the top. When that's not possible, he waits calmly, sometimes for several hours. If he doesn't like the spot, then he goes into the adjacent forest and rushes out to greet me on my return. Even in the depths of winter when I'm ice-climbing, he finds a spot and waits for me. I am always impressed by how little this bothers him.

He also demonstrated his ability to understand complicated messages once in my office. I just wanted to pop into a shop opposite, but Kuksi came down the two flights of stairs with me to the front door of the building. When I realised he had followed me, I told him to go back up to the office and that I would be right back. He turned around immediately and ran back up. A phone call to check confirmed that he had indeed gone back in and was waiting for me there.

I can also ask him what he wants. If I go for a walk, he is usually with me, but, if I decide to go running instead of walking then he can decide for himself if he wants to stay at home. I have a dog trailer for when I go cycling. Kuksi decides for himself whether he wants to ride in it or run alongside the bike.

A special form of interaction is playing. This can happen in different ways, but it is made a game by us determining the rules together and knowing that whatever we do playfully is not to be taken seriously. In play, we can fight, bite each other, hold each other down and roll on the floor. When we do this, Kuksi growls and shows his teeth in a way that could be frightening, but he also repeatedly shows me his characteristic play-face to let me know that he doesn't mean it seriously. The invitation to play is clear and unmistakable, the backside is high and the head is on the floor with front legs outstretched left and right. Spinning in circles and a special facial expression are also part of the repertoire. Then we chase each other, tug on opposite ends of a stick or wrestle with each other. There are regular pauses where we use our play-faces to check with each other whether the game should continue. This also means that in play, you sometimes act weaker than you really are and that you can lose a fight.

A special type of game is the 'follow the scent' game. It's a well known fact that dogs have a far better sense of smell than humans, but still, Kuksi seems to be exceptionally gifted, even among dogs. He lets me have a five minute head start that I use for running through the forest, over meadows and streams. Then he tracks me down with his nose in a flash, not even losing my scent when he's in full gallop. It's clear that he needs to employ a high level of conscious thinking in this activity. Once, I laid a trail along a forest track and then ran back along the same trail about 20 metres and jumped from the trail into a stream, crossing over to the other side and then climbed up into the steep forest, finally hiding behind a tree. As usual, Kuksi went galloping along the forest track. Suddenly, he noticed that the scent had gone dead, so he went back to the beginning to pick up the scent only to promptly lose it again. At this he let out a loud yowl and ran back again. This time his sniffing was very slow and deliberate. He stopped where I had jumped into the stream and inspected the area carefully. When he stepped out of the stream on the other side, he zig-zagged to the left and right until he was able to pick up my scent again, then it took him no time to arrive at my side. No question about it – even for a dog with a champion nose, following a scent is detective work.