Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

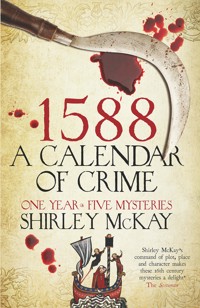

- Serie: 1588: A Calendar of Crime

- Sprache: Englisch

A grisly murder. A vanishing corpse. A secret romance. A ghostly tale. An innocent accused. 1588. It is a dark and turbulent time. Scotland's queen has been executed, the Spanish king seeks revenge, and the people of St Andrews cling desperately to the rhythm of the old ways. The ancient burgh is renowned throughout Europe as a seat of Church and learning but it is also a town full of suspicion, conspiracy and murder. Shirley McKay sets her intriguing and sometimes comic tale around the key points in the calendar: the four quarter days of Candlemas, Whitsun, Lammas, Martinmas and the feast day of Yule. When the first victim is discovered on Candlemas Eve, Hew Cullan, scholar and lawyer, is called upon to investigate; the dark side of the sixteenth century comes alive in a rich tapestry infused with the textures of history and folklore, woven by a master crime writer.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 522

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1588A CALENDARof CRIME

By the same author

HEW CULLAN MYSTERIES

Hue & CryFate & FortuneTime & TideFriend & FoeQueen & Country

This edition published in Great Britain in 2016 byPolygon, an imprint of Birlinn LtdWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 978 1 84697 363 5

eISBN 978 0 85790 911 4

Copyright © Shirley McKay, 2016Illustrations and calligraphy © Cathy Stables, 2016

The five individual books in this novel are published separately as eBooks

The right of Shirley McKay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

Text design by Studio MonachinoPrinted and bound by Scandbook AB, Falun, Sweden

Endpapers: Calendar, Monogrammist HK (engraver), Rijksmuseum, The Netherlands. Page 298: From Jost Amman’s Stände und Handwerker mit Versen von Han Sachs (1884), Wellcome Library, London.

CONTENTS

BOOK ICandlemas

BOOK IIWhitsunday

BOOK IIILammas

BOOK IVMartinmas

BOOK VYule

1588: FOREVER AND A DAY

A LIFE SHAPED BY SEASONS: HISTORICAL NOTES

GLOSSARY

BOOK I

Now diverse secret agues breedBe choice of food, beware of cold:Abstain from milk, no vein let bleedIn taking medicines be not bold

RICHARD GRAFTON’S ALMANACK,A brief treatise, conteinyng many proper tables and easie rules… (1571–1611)

I

The candlemaker’s boy was thankful for the moon. Without its friendly glare, he would have to make his way through darkness down the path adjacent to the cliff, perilous by day, let alone at night. And no one but a lunatic would care to take that chance.

A crowd of yellow pinpricks clustered at the Swallowgate, where lanterns cast a dimly well-intentioned light, but over to the west the darkness pooled and chasmed, blacking out the cliff top and the gulf beyond. And westward was the crackling house, set back from the town, where the salt winds might snatch the rank air, and the sea water carry it off.

In the year of plague, the dead had been laid down to rest in this place. So much that was noxious was settled in the wind. The candlemaker’s boy muttered out a prayer, and shuddered as he passed. He thanked God when he came upon the low flame of the crackling house, swinging at the door as the law required. A slender skelp of taper guttered in the draught; the candlemaker grudged to spare the smallest light.

The boy entered the crackling house, pulling off his hat. ‘I have done what you asked.’

The candlemaker, bent over his great greasy pot, did not look up. ‘Is that a fact?’

‘I went to a’ they houses, all the ones you said. The auld wife at the last one wasnae best pleased. She wis not pleased at all.’

‘No? And why was that?’

‘She said ye had not sent her all that she had asked for. And she did not like the candles that you sent. She said that the tallow was filled full o cack.’

‘That guid wife is a lady. She did not say that.’

‘No. She said – ’ the candlemaker’s boy assumed a high-pitched plaintive voice, pinching at his nose, ‘Please to tell your master, there is offal in it. Oh, but it does stink!’

‘You do the lady wrong, to mock at her like that,’ the candlemaker warned.

‘She is not so gentle, as you seem to think. She says she will not pay you the prices you demand. She says you have extortioned her. She says she will report on it to the burgh magistrates.’

‘She will not do that. And she will pay the price. For we ken what it is that she does with her candles.’

‘Do we?’ the boy asked, unsure.

‘Of course we do, you loun. What did she gie to you, to thank you for your pains?’

‘Nothing. I telt you, she wasnae pleased.’ The boy stamped his feet. ‘Three miles through the dark, and the wind was fierce.’ He did not tell the fear, the horror he had felt, to shiver in the great hall of that wifie’s house, where, he was quite certain, there had been a ghost.

‘Cold are ye? Come by the fire.’

‘Nah, I’m a’right.’

‘Did you no hear me, son? Come by the fire.’ The candlemaker left his post to slide a helping hand around his servant’s shoulder. He grasped the boy’s ear, and twisted it sharply. The boy gave a yelp. ‘Whit was that for?’

‘What did she gie ye, ye wee sack of shite?’

‘Nothing. I telt you,’ the prentice boy whimpered, wrenched by his ear to the rim of the pot. ‘For pity, you will hae ma lug off.’

‘Aye, and I might.’ The candlemaker let go of the ear, that was throbbing fiercely, radiant and red, but before the boy could cup it in a cooling hand he felt the candlemaker’s fingers strangled in his hair, forcing him down to the filth of the bath.

‘Mammie!’ He could say no more, for the fumes from the tallow filled his eyes and lungs, and his legs beneath him buckled at the stench. A little of his forelock flopped into the fat, and began to stiffen as his master pulled him up. ‘Why wad ye do that?’ he wailed.

‘For that you are a liar, and an idle sot.’

‘I did not lie. She gied me naught. I telt you. She was cross.’ The boy was snivelling now. Perhaps it was the fumes. He could not help the streaming from his nose and eyes. He ought to be inured to them. He ought to be inured to the candlemaker’s wrath. It was not the force of the fury that disarmed him, and caught him off his guard – fearful though it was – it was that the moment for it could not be foretold. The candlemaker’s boy could seldom see it coming; he had not that kind of wit. And, when it came, it knocked him from his feet.

‘Mebbe that is true,’ the candlemaker said, and the boy felt his nerves shiver to a twang, ‘but that does not excuse your fault in your craft. What do you say to this?’ From their place upon the rack he pulled down a rod of limp tallow candles, all of them shrunken and spoiled. ‘What do you say?’

‘They were too early dipped.’

‘And what limmar dipped them?’

It struck the boy, quite forcefully, that it had not been him. Perhaps it had been the candlemaker’s wife. He gathered to his service what he had of wits, and managed not to say so. ‘Ah dinna ken,’ was what he spluttered out.

‘You do not ken?’ The candlemaker raised his arm, and paused, to rub at it.

The candlemaker’s boy took courage from the pause. ‘I heard the surgeon say, ye must not strain yourself.’

‘Not strain mysel’?’ The candlemaker glowered, and let his sore arm drop. ‘I’ll show you strain.’ But something in him slackened, and appeared to slip.

‘Will I do the work again?’ the boy suggested then.

‘I’ll see to it mysel’. You will pay for the waste, out of your wages. Awa with you, now. Hame to your lass. Look at ye blubber. Ye greet like a bairn.’

The candlemaker’s boy rubbed his nose on his sleeve. ‘Ah dinna greet.’

It was the odour of the grease pot that had caused his eyes to stream. Surely it was that. He could feel the tallow drying in his hair, the tufted strands of sheep fat pricking up on end. His master could see it, and his humour changed. ‘Tell your lassie I have dipped for her a scunner of a candle. She may put her flame to it, if she can stand the stink.’

The boy’s wit as always was slow to ignite. ‘Whit candle is that?’

‘You, you lubber, you.’

It was not for kindness, nor from common charity, that he sent the lad away. Charity would be to give the boy a light. Instead, he let him flounder, on the dark path home. And if the candlemaker stayed to work on through the night, in spite of his sore arm, then he had a purpose for it that was all his own. There were certain kinds of business played out in the darkness, and best prospered there; business of that sort had no business with the boy.

At nine of the clock, or a little before, a visitor came. He had brought with him his own little lantern, in a sliver of parchment, like the ones the small boys bound up on to sticks, to carry back from school on winter afternoons. The candlemaker thought it would not last the wind, to see the bearer home.

The visitor was well wrapped up. Perhaps against the wind; perhaps against the flavour of the candlemaker’s shop – the crackling had a savour not to everybody’s taste; perhaps because he did not wish to show the world his face. He wore a kind of cowl, a long and shapeless gown, a hood up round his head. His muffler could not mask the feeling in his eyes, which were pale and agitated. He looked about, and back, as though the shadows of the night might engulf him on his way. His words, when he spoke, were low and unwilling. ‘So. I have come. As you said.’

The candlemaker lifted out a row of candles from the pot. He stood awhile, considering. Then he placed them carefully to dry upon the rack, and took up another row, preparing them to dip. ‘A moment, if you will.’

‘Yes.’ The visitor accepted, and remained politely, while the row was dipped. It was not until a third descended his impatience showed itself. ‘I cannot stay so long. If you do not have what I want —.’

The candlemaker showed no flicker of concern. ‘I have what you want. But this is a business that cannot be rushed. If it is rushed, it will spoil, do you see?’

‘I see that.’ The visitor was courteous, conciliatory, even. The candlemaker sensed that he would not put up a fight. ‘But, I think you said to be here before nine. And it is nine now.’

To confirm this, the St Salvator’s clock at that moment could be heard to strike the hour.

‘I believe, sir, it was you that fixed upon the time,’ the candlemaker said.

The visitor conceded, ‘Ah, perhaps it was. My pardon to you, sir. But since you are still occupied, and I may not stay long, I shall come again. Tomorrow, if you will.’

The candlemaker smiled. ‘Aye, just as you like. Though I must warn you, sir, that I cannot promise I will have tomorrow all that ye require.’

‘But surely… since you say you have it now…’ The visitor, plainly, was baffled by this.

‘I have it for ye now. And, sir, I have kept it for you, at some trouble to myself, when the commodity you look for is very dear and scarce. If you will not take it now, I cannot be expected to have it still the morn.’

‘But I will take it now, if you will only give it to me!’ the visitor exclaimed.

‘Very good. I will. When the rack is done.’ And the candlemaker, blandly, went on with his work.

The candlemaker dipped, for such a length of time as he could see the patience of his customer last out; he judged it very fine, like the grains of sand running through a glass; and when he saw that the great mass of sand, all in a rush, was about to flood out, he straightened up quickly, and said, ‘If you will take it now, sir, I will fetch the stuff.’ And from a shelf in the shop, where it opened to the street, he produced a slender box. This he opened up. ‘Fine, is it not?’

‘It is less substantial than I had supposed. That is, for the price…’

‘As to that,’ the candlemaker intercepted smoothly, ‘it comes in at two pounds, six shillings and sixpence. And, I suppose, you would also like the box. A shilling for the box and the paper in it. I will not count a penny for the scrap of string.’

The visitor blinked at him. ‘Two Scots pounds, we said.’

‘So much had I hoped for. I do not set the price. And, as I have said, it was hard to find. But the profit to you is, I ask nor answer questions. Whatever you will do with it, is your own affair.’

‘I understand you, sir. The pity of it is, I cannot pay that much,’ the visitor confessed. ‘This is all I have.’ And, to prove his point, he emptied out his purse.

The candlemaker hesitated. ‘I do not always do this. But, as I believe, you have an honest face’ – so little of that face as was left to view. ‘Give me the two pounds. And you can owe the rest. Can you write your name? Then put it in this book.’ He took out from the counter a fat leather notebook, and opened to a page, on which the date was written: First of Feberwerrie. ‘That makes, in all, seven shillings and sixpence.’

The visitor glanced at the book. He squinted at the figures. But he did not seem convinced. ‘Seven and sixpence? What are your terms?’

‘Pay the money on account by the first of March, and the debt will be cleared, without further cost. If you cannot pay, interest will accrue, but we need not speak of that until the debt is due. Sign for it now, this very day, and you may have the stuff to take away with you. Or, if you will not, I must offer it for sale.’

The visitor agreed. He signed his name and left, the burden of his dealings bundled in his cloak. He fled the crackling house, as though the devil’s spur and pitchfork pricked behind him. He did not look back. And the candlemaker’s prophecy was proven to be right, for his sliver of a lantern did not last the wind.

The candlemaker meanwhile worked on through the night. Though he had made a profit he did not feel quite satisfied. He felt a deeper sense that something was not right. And he did not feel well. His legs were weak and tired. His forehead and his forearm had both begun to throb. The bandage on his arm was bulging, hot and tight. He sat down in his chair and loosened it a little, letting out the cord. He let his dull eyes close, and soon he was asleep, so shuttered to the world, he did not hear the latch.

Frances had not slept. For a while she shifted, soundlessly sought rest, before she slipped the shackles of the heavy quilt and found solace in the shadows by the window sill. Hew felt the coolness of her absence in the bed, and woke to find her gazing out upon the moon. ‘Is there aught amiss?’

‘Nothing is amiss.’

‘Will you come to bed?’ He felt for the tinder box, striking a flame. Frances said, ‘Don’t.’

Bewilderment clutched at him still. ‘Do not light the candle,’ Frances said. ‘So little have we left, of the purest wax. Bella says tis hard to come by, at this time of year.’

‘Tomorrow, I will fetch you some.’

‘I would not have you trouble, for my own indulgence.’

‘It is not indulgence. You shall have the best.’

Frances had developed an aversion to tallow, in candles of the common sort, as to the scent of flesh, and fat of any kind. It was parcel of a change in her that mystified and baffled Hew, though his sister Meg assured him it should not be feared. He had done what he could to keep her in comfort, over the last seven months. Now the store of beeswax, apparently exhausted, caused him some concern. The cost of the candle meant little to him; yet scarceness was a thing he could not help but count. The town trade in wax had been stifled at the plague, where the sweet balm of the wax-maker’s craft had conspired, drop by drop, to draw him to his death.

‘Besides,’ Frances said, ‘there is light enough. Tomorrow night, I doubt, the moon will be quite full.’

There was truth in that. At this time of year, on a cloudless night, there was more light to be had in the glancing of the moon than in the laggard day, when the sun struggled blearily across the sullen sky. So it seemed to Hew, as he rode out in the blinking of a bloodshot dawn, to fulfil his obligations at the university.

The porter at St Salvator’s hailed him at the gate. ‘Good day to you, professor. Doctor Locke is called out, urgent, to a casualty. He asks if you can read for him his early morning lecture, on the chiels, an such.’

De caelo et mundo, Hew interpreted. ‘Certainly I could. He did not, I suppose, report the nature of the accident?’

‘Only that it was a most woeful and perplexing one.’

Casualty, Hew thought, was a curious word, and no doubt one the porter had not thought up by himself. Hew’s closest friend, Giles Locke, was Visitor for Fife, reporting to the Crown on unexpected deaths. Hew was accustomed often to assist him, and, in legal cases, to assume the lead. Where there was a casualty he felt an interest too, and a little piqued to be left behind.

‘He will be obliged to you. For he was afeart the students will revolt, and take it for a holiday. They may not have a holiday, though they will entreat for one, on account of Candlemas.’

The old tradition was, in grammar schools at Candlemas, the scholars gave their masters silver as a gift to fund the cost of lighting in the schoolroom for the year. The schoolmaster would grant them a play day in return. And college students hankered still for such small indulgences.

‘The wind is, we shall have a royal visitation, in the Whitsun term. Wherefore, says the doctor, keep them to their books. And the student Johannes Blick is keen to speak with you,’ the porter went on.

Hew smiled at that. ‘No danger, I suppose, that he is pleading for a holiday?’

‘None at all, I fear.’

Johannes was the son of a Flemish merchant, in his final year. In age in advance of his fellow magistrands by a year or two, he outstripped them by a score in intellect and aptitude. And there was no doubt, when the king’s commissioners came to make their inspection, Johannes would stand out among them as a shining star. Yet day to day, his brightness was a strain. When his tutor could not fathom to the bottom of his questions, he had turned his attentions devotedly to Hew, an attachment which occasioned as much mirth among the college, as it did relief. Hew had done his best. He had lent him books, and given many hours to hearing out his arguments. He liked Johannes well. Yet still there were days when he would sigh and sink to hear the fatal words, If I might for a moment, sir, intrude upon your time. Then time would run like sand, and never be enough.

‘Forewarned is forearmed. I thank you, Will, for that. Then all is well, besides? No more that I should know?’

‘Naught else, of note, except you have a visitor. I left him in the cloister, where he can do no harm. I did not care to think what Doctor Locke would say,’ Will concluded cryptically.

Barely had Hew entered through the archway to the square when Johannes fell behind him, matching step for step. ‘Salve, Master Hew. I trust you are quite well. If I may intrude a moment on your time…’ Johannes spoke in perfect Latin, well-tuned and precise. His clear pedantic sounding filled Hew with dismay.

‘Salve, Johannes. I am quite well. You find me in some haste.’

‘Then I shall not detain you, sir. I wanted, simply, to thank you for the help you were kind enough to give me, and to return your books.’

‘But surely,’ Hew, despite himself, could not help but say, ‘you have not read them yet?’

‘I have, sir, read them all. If you have a moment, I will fetch them now. I have made some notes, of the principal matters contained in the books, and the principal questions, and objections, arising therein, which I should very much like to discuss with you.’

‘Facile. Of course. But, alas, not now. Speak with me after the lecture,’ Hew suggested, desperately.

‘What lecture, sir, is that?’

‘Aristotle, De caelo, which I must give in place of Professor Locke.’

‘I have heard Professor Locke, on the movement of the spheres, and of the elements. Most illuminating. I should like to hear, indeed, your own interpretation of it.’

‘The lecture is no more than a reading of the text. Trust me, Johannes, I shall not deviate at all, from the version you have heard before from Doctor Locke.’

Johannes smiled the gentle smile that so rarely broke upon his solemn bright blue eyes, transforming his face from a paragon of seriousness. ‘Now that is a thing that I very much doubt.’

The student was disarmed, evaded for the while, and Hew came to the cloister, to confront the visitor, whose purpose had been pressing on his mind. For here was Roger Cunningham, who once had set his wits so fiercely against Hew. A student at the college, Roger had withdrawn, in a fine show of arrogance and supercilious pride, before he was expelled, and bound himself apprentice to a barber-surgeon. Giles Locke in particular was hurt by his deception, and found his dereliction hardest to forgive.

Roger faced him boldly. ‘Well, you took your time.’

Hew did not rise to this. He sensed, behind the swagger and display, a current of uneasiness. Roger was not comfortable, or brave as he appeared. In the corner of the square, and at the chapel door, a group of students gathered, pausing there to stare, at one whom they no longer counted as their friend. Roger was unnerved. And that was rare enough.

Hew saw the students off, a brusque wave of his hands, to scatter them like birds. They would not fly far. ‘What is your business here?’

‘There has been a death,’ said Roger, ‘in the crackling house. John Blair the candlemaker. Please, will you come?’

There was meekness in his tone, and in his demeanour, which astonished Hew. ‘Did Doctor Locke send you to fetch me?’

‘No, sir, he did not. I am asking you. My master is suspected as complicit in his death. Occasion and the circumstances do inform against him. I wish you to defend him,’ Roger answered simply. ‘For it is not true.’ What did it cost him, to put such a case?

‘Why would you ask me?’

‘I know of no one else.’

That much was honest, thought Hew. ‘Suppose that it is true?’ he asked Roger softly.

‘Then, I suppose, you will find it out.’

‘Understand, I make no promise. I will come and see.’

Johannes saw them pass, and called out in astonishment. ‘Are you going out, now? Will there be no lecture? What about the students, waiting in the hall?’

Roger grinned at him. ‘Tell them it is Candlemas, and they have a holiday. They never liked you half as much, as they will like you now. Close your mouth, Johannes, it is dropping to the floor.’

Johannes said, reprovingly, ‘I know this Roger, sir, that was a student here. I cannot find in him an honest heart or pure. I pray to God you do not place your trust in him.’

‘Before the year of plague, there were three or four candlemakers working at the crackling house. John Blair was the last,’ Roger had explained. ‘He leaves behind a wife and a prentice boy. At Martinmas, at slaughter time, he took on extra hands. But for the most part, he worked on his own. He liked it like that. His journeyman Tam Cruik, when he had served his time, found work as a straggler, travelling to the manors and the country farms to make their candle for them when they kill their lambs. Perhaps he comes to yours.’

Hew did not reply. They had come upon the place. And his answer had been swallowed, stifled by the smell. The stench of the tallow had the curious effect of dulling down the image that appeared before his eyes, stripping it of force, as though the strength of the assault on that most sensitive of senses dampened down the rest.

The crackling house was narrow, eight foot wide at most. A window on a working day opened to the street, a counter folding down to hold a small display of the candlemaker’s wares, for any who were stout enough to seek them out at source. Most would be content to wait till market day, when the candlemaker’s boy would go forth with his creel to cry them by the cross. The shutters now were closed, the counter folded in. In the chimney a large pot of fat hung suspended, cloaked in a sooty black smoke. Someone had dampened the flames of the fire, in time to save the house from burning to a crisp, the tallow having caught a little as the pan boiled dry. The silt that smouldered still explained the acrid smell. On a board beside were several moulds of copper and a metal trough, where melted grease was poured, and the candles dipped, while a rusting pail oozed tallow fat unrinded, marbled and veined with pale pink and blue, to which the rank rumour of sheep flesh had stuck. Two small windows, barred, looked out on a yard, to allow the smoke a pitiful retreat, and in this yard, come fair or foul, the candlemaker rendered down the raw slabs of the tallow, polluting the fresh air for a mile around.

Hew allowed his eyes to rest a moment on these things, to fix them in his mind. The gross slab of sheep fat left so much of an impression there, it came back to him when he next closed his eyes; and when he fell asleep, it merged, indistinct and irresistible, with the vision of the candlemaker – which he turned to next – and they became so blurred, his waking mind could scarcely tell the two apart. The figure of the man dissolved into the tallow, sallow, slick and bloodless, sundered from the flesh.

The candlemaker sat, or somehow had been stuffed, stiff among the cushions of a single settle seat; so broad was his beam he filled its girth completely, packed close as a candle poured into its mould, with no gap for air. It would take a timmerman to prise his carcase out. He was stripped down to his shirt, a loose tent of flax flowing over his breeks. His points were undone, and his sleeves were rolled up. Both palms lay open, slack, in his lap, his elbows constrained by the sides of the chair. From his forearm to the right, a little past the joint, a bandage had been pushed, loosened from its place and very lightly flecked. The arm below was drenched with rivulets of blood, that streaming from the place they first had found a pulse had coursed the long way down through woollen breek and hose and pooled upon the floor, coming to a close at the candlemaker’s shoe, where they had discoloured to a sympathetic brown. A second stream had cupped in the candlemaker’s hand, thick and darkly red.

Standing on each side, attendant on the corpse, were, to its right, Sam Sturrock the surgeon, and to the left the physician Giles Locke. Between them a lad, of eighteen or twenty, fiddled with his cap and hopped from foot to foot, the one small anomalous flutter of life.

Giles was first to speak. His presence in a crisis, circumspect and steady, always reassured. But Hew could read no comfort in the voice that said, ‘What brings you, Hew? Is there something amiss at the college?’

‘Nothing is amiss. Roger came to call for me, and brought me here to help.’

‘Then, as I suppose, there will be no lecture,’ Giles concluded bleakly, more resigned than vexed. ‘And it is hard to fathom how you hope to help. Still, since you are here, you must now bear witness to this sad affair.’

Hew understood, at once, that he should not have come, that Giles Locke had a purpose, in trying to ensure that he was otherwise engaged. As witness, he was bound to give evidence in court. And if he were to be called to serve upon the jury – since jury members always had an interest in the case – he could not be allowed to speak for the defence. The white face of the surgeon, whose misery was plain, who looked as sick at heart as the candlemaker’s corpse, convinced Hew a defence was soon to be required. But since he had quite wittingly intruded on the fact, it was now too late to offer to withdraw. He had made himself a witness, willingly or not. In which case, someone else would have to speak for Sam.

‘The defunct is John Blair,’ Giles went on. ‘You knew him, perhaps. His friends called him Jock. He was sometime the beadle, at the town kirk.’

Naming him had humanised the carcase in the chair, assigning it a pathos Hew did not like to admit. The candlemaker’s head had fallen to one side, slipping from its pillow as its owner fell asleep, and – Hew thanked the Lord – the eyes were closed. He forced himself to look upon the candlemaker’s face, and forced himself to see, though the features slipped and shrank upon the bone, as though the lifeless flesh had melted in the fire, that there was something there he dimly recognised. He remembered one John Blair, beadle in the kirk, bustling through the town with prurient efficiency. Was it not John Blair, had turned out the young Dyer bairns for fidgeting in kirk, when their da had died? And the same John Blair, that took a throaty pleasure in the stripping of a whore, exposed for all to jeer at in the market place? And when Agnes Ford was taken for a witch, was it not John Blair had kept her from her sleep, and applied her torments keenly and assiduously?

‘Sam Sturrock, the surgeon, ye ken,’ the doctor continued, relentless. ‘And this lad here is John Blair’s prentice, Alexander Forgan.’

Alexander Forgan said ‘Eck,’ unused to, and recoiling from, the full force of his name, which woke in him a kind of fearful superstition.

‘Eck,’ conceded Giles, ‘tell to Master Hew here all that you told me, that he may be a witness to your true account.’

Eck surpassed himself, with a flush of pride, for despite his squeamish pity at the scene, and a vague suspicion things did not bode well for him, a thrilling kind of horror bubbled in the boy, and he was brimming over with the tale he had to tell. ‘It was I that found him. Ah fund him, d’ye see?’

The matter amounted to this. He had last seen his master, alive, between eight and nine of the clock, the night before. He thought it must be closer to the nine, for he minded that the bell had rung, to mark the college curfew, just as he reached home; he lived landward, with his mother, half a mile away.

He had spent the day, and the evening after dark, making some deliveries of candles through the town, and some way beyond. It was a busy time. And it did not surprise him that his master lingered on, working through the night. He had known him work all the night before, to see the orders done. When he was tired, he would sleep in his chair. His wife was forewarned not to expect him.

At the mention of a wife Hew’s stout heart sank a little. Sam Sturrock stood and listened all the while, saying not a word, as Eck babbled on.

The master was not well. He took very bad headaches, and sick with it too, that hampered him cruel in his work. He consulted with the surgeon for it, and, on Saturday, went to him to be bled. The surgeon said to rest. And he had rested, properly, on the Sabbath day. On Monday – yesterday – he said he was recovered, and came back to work. He had a deal of work, since today was Candlemas.

‘Is Candlemas observed still?’ questioned Hew. He did not think that Andrew Melville, kneeling on the flagstones of his college cloisters, would call for many candles to illuminate his prayers. The reformed kirk was dead to such whims.

‘For certain, sir, hereby. For it will ay be Candlemas. Though they reform the kirk, they can’t reform the calendar.’

Here Hew and Giles exchanged a glance, and Giles informed him wryly, that the pope in Rome had done that very thing.

‘Oh, the pope in Rome,’ Eck repeated scornfully, with the blithe contempt of a true bairn of reform, too young to have an inkling where his world was formed, or what fuelled the superstitions to which he succumbed. ‘We do not keep it, mark you, in the popish way. But guid folk want new candles, as they always will.’

‘You do not, I suppose,’ Hew could not help but say, ‘have any made of wax?’

‘We are not wax merchants, sir. We sell tallow candles, and soap. We have, if you will, some very fine soap,’ Eck replied, mechanically. Hew shook his head. He could not bear to think of the candlemaker’s soap, moulded from the scum of tallow in the vat, against Frances’s white skin.

‘But my master, perchance, may procure some to order, if you desire …’ Here Eck tailed off. The horror of the fact had dawned on him in full; his master would not order anything again. ‘Oh, sirs, he is dead.’ Recognition wrung from him a solitary tear.

Giles said kindly, ‘There. You have done quite well. Perhaps you should go home.’

‘Oh, but I cannot,’ wailed Eck, ‘while there is work to be done.’ He looked about him hopelessly, for want of a direction, which at last was settled in the pail of fat. ‘That should not be there. If you do not mind, I will tak it outside.’

‘Do, if it will please you,’ Giles encouraged him. They watched as the prentice boy shouldered the pail, and carried the tallow fat out to the yard. He set down his load, and stood scratching his head, the impulse to action apparently fled, quite at a loss as to what to do next.

Sam Sturrock, all this while, had spoken not a word. Giles turned to him now. ‘Will you speak to us, Sam?’

The surgeon said, tonelessly, ‘I have telt you all I can. There is nothing more to add.’

‘Please, will you tell it to Hew?’

Sam did not respond. It struck Hew that the man was in a state of shock. And in his shock he was in no fit state to answer to such questions, no matter in what gentle manner they were put to him, and by so kind an inquisitor; perhaps, especially in that case. Giles Locke saw it too, for he proceeded patiently, ‘Sam, you must go home. I will visit you there, before I submit my report, and put the question again. In the meantime, you must give me your word you will desist from practice.’

The surgeon nodded merely, staring at the corpse.

‘There is nothing, now, that you wish to add? You say that John Blair consulted you, about recurring headaches. That on Saturday, you opened up a vein for him, and told him he should rest?’

‘That is what I said.’

‘And you will not explain, why you chose this course, at such an inauspicious time, that nature, sense and physic all were ranged against it?’

Sam Sturrock whispered then, ‘He wanted it that way.’

‘He wanted it that way? And did you not tell him the danger?’

‘I telt to him the danger. But he was not deterred. He professed himself in such an agony and heat, the most extreme and violent measures were required.’

‘And did you never think to consult with a physician, what remedy was best in this exceptional case?’

The surgeon bowed his head, and answered not at all.

Roger exclaimed, ‘This is not right. It cannot be right.’

Giles turned his gaze on him. ‘Were you with your master when he cut the vein?’

Roger faltered then. ‘No, he sent me out.’

‘Therefore, you have no purpose here, no place to speak for him. But it seems strange that he sent you away. Did someone else assist you, Sam?’ Giles persisted quietly.

‘There was no one else.’

‘And is this the cut to the vein that you made?’

The surgeon answered, carefully, ‘That is the place.’

‘It cannot be. Tell them,’ Roger implored. ‘Will you not speak?’ When the surgeon would not, Roger attempted to walk the man home, but this was repelled.

‘Cease, Roger. Stay. Accept what must come. What has been done cannot be undone. There is no hope.’

On this grim command, Sam departed alone, and Hew placed a hand upon Roger to hold him. ‘There is a boy, in the yard outside, in want of a strong drink.’

‘And what is that to me?’ Roger answered rudely.

‘Apposite,’ said Hew. ‘That boy has a tale to spill. And when he is over his dread – which he will be quite presently – he is like to spill it to the first friend at hand. That friend will be you. He will trust you best, for you are most alike.’

‘We are nothing alike,’ Roger retorted, his superfluous pride spilling over at this. ‘How can you think so? He is an ignorant loun.’

‘And you a presumptuous one. Yet you have more in common than you may suppose. You are close to him in age. You are prentices, both, and both, for want of a master, as likely to be cast adrift. If you cannot in your conscience relate to his predicament, then he has the wit to relate to yours.’

His own situation so forcefully brought home to him, Roger said sulkily, ‘What should I ask him?’

‘Use your own intelligence to find out what he knows. Since you are so clever, that will not be hard.’

‘Aye, but he stinks.’ There was such a fit of childishness beneath his stubborn pride, despite his pompous posturing, that Hew was moved to smile. He felt, inexplicably, a fondness for Roger, who was not as worldly as he liked to think.

‘Of course he will stink. He is a candlemaker’s boy. But I have seen you carve your way through gobbets of green flesh, and hold your knife and nerve. Surely, as a surgeon’s page, you have not grown fastidious.’

‘Mebbe,’ Roger scowled, ‘I like my foul flesh dead. Well then, for Sam Sturrock’s sake I’ll take him for a drink. Since we are puir bairns both, we’ll charge the drinks to you.’

‘What are you about, Hew?’ Giles asked his friend, when the two of them were left together in the room, with no matter still between them but the candlemaker’s corpse.

‘Roger asked me to investigate the candlemaker’s death. He cannot comprehend that his master is at fault.’

‘He will, quite naturally, not want to comprehend it, in view of its consequence, not least for himself.’

‘Doubtless,’ Hew agreed. ‘You do not think, at all, there may be some hope in it?’

Giles was quiet for a moment. Then he shook his head. ‘Do you mean for Sam? I wish I thought there was. I like Sam Sturrock well. I have always believed him an honest, a credible surgeon. It grieves me in my heart to find him brought so low. And yet, I cannot help but find he is at fault, and gravely so. His conduct has led, quite directly, to this poor man’s death, through negligence, or worse. You saw his demeanour: he is quite aware of it. He offers no defence, for there is none to give. For every kind of fool that ever read an almanack can tell you, clear as day, there never was a time of month less apt for letting blood, nor season less auspicious for it, than the present one.’

‘As any fool might say,’ said Hew. ‘But men of physic make exception, surely, for a special case.’

Giles favoured his old friend with a narrow look. Presently, he said, ‘Men of physic do. And if you have the will to browse among my books, you will find recorded there whatever such exceptions may be safely made. I do not have the time just now to go through them with you, for I must tell a guid wife she is now a widow. I will see you at the college when that heavy work is done.’

In Giles Locke’s turret tower, Hew had spent the best hours of the afternoon reading on phlebotomy. ‘Let not blood at any time,’ the book began oppressively, ‘unless there is great cause.’ Hew wrote in a column all the arguments against: the weather, the season, the phases of the moon. In addition to the warnings set out in the almanacks – the present moon in Leo was especially inauspicious – there were impediments most pressing to the candlemaker’s case: the foulness of the air, the nature of his work, the severity of pain of which he had complained, the wobble in his wam, with vomiting and flux, his agitated state, his want of rest and sleep, his corpulence and indolence, the diet he had kept. In the column ‘for,’ he could write but one, and that he did not find in any kind of book. It was the surgeon’s own and only explanation: ‘Because he asked me to.’ And it was clear to Hew that made no kind of sense.

He was sitting hopelessly, chewing at his pen, when he was distracted by Johannes at the door. ‘Salve, Master Hew. I was told by the porter that you might be here. I have no wish to disturb you.’

‘Don’t then,’ muttered Hew. He had not intended that it should be heard; he spoke it in the Scots, but Johannes was a student of extraordinary faculties. He looked a little hurt, but not at all deterred. ‘What I have to say will not detain you long. You have been so good, to help me with my work. If you can say a time, that is most convenient to you, I would like to thank you, and return your books.’

‘Johannes,’ Hew said wearily, ‘there is no need to thank me. Please, keep the books. They may profit further study.’

‘As to that,’ Johannes said, ‘I have made some notes.’

Hew stood up, exasperated. He took from the shelf the first book to hand. ‘Here is a book that you have not yet read. It will profit you well to turn it into Latin’ – he glanced upon it quickly – ‘ah, to turn it from the Latin, into native Scots. That I think is somewhere where you lack experience.’

Johannes said, baffled, ‘It is a book about bees.’

‘And bees are, indeed, a very fine exemplar. You may come and see me, when the work is done.’

Had Hew been left for longer to his own devices, he might well have repented of this treatment of Johannes. But barely had he turned back to the case in hand, when Doctor Locke returned, with Roger at his heels, and both of them brought news that chased it from his mind.

II

It was chance alone that brought the two together; they had met on the turret stair, where Giles overcame his antipathy to Roger, sufficient to allow him access up to Hew. Roger spoke first. ‘You were right enough about the prentice boy. He had a tale to tell. His master, it seems, was a hard man to work for. He was little liked. There were many people might have wished him harm.’

‘It matters not,’ Giles pointed out, ‘how many may have wished him harm. One man harmed him. That was Sam. And if you mean to say he had a reason for it, that hardly helps his case.’

Roger said, ‘Hear me, for there is more. The boy’s last commission on the eve of Candlemas was to deliver candles to a guid wife out of town. That woman was by no means well disposed towards his master. The boy believes she put a curse on him. He is quite convinced, that she is a witch. He saw a spirit in her house. Perhaps it was that wife that killed the candlemaker, caused his vein to burst by the casting of a charm.’

Giles retorted, ‘Pah!’ an expression of disgust which he did not clarify, by gracing it with words. But Hew, more circumspect, inquired of Roger if he knew the woman’s name.

‘She is, I understand, some relation to the Balfour family. She is aged, far beyond the common course of life, and she lives in a coven, by the Poffle of Strathkinness, two or three miles from the town.’

Giles corrected, with a snort, ‘She is a distant cousin of the Balfours. She has lived in seclusion now for many years, in a house she rents from them. Her given name is Ann. She is a lady, though a very poor one. And she is by no means a witch.’

‘Do you know her?’ asked Hew.

‘She is a patient of mine. And if you will libel her, with this vile lie, I will take it much amiss.’

‘Who says,’ Roger countered, ‘that it is a lie?’

The doctor turned on him. ‘There speaks the boy, who has no faith in God! You do not for a moment take her for a witch, for you do not believe in them. And yet you will not hesitate to propagate the slander, for the sake of Sam. It is not just, nor honest. It is vicious, cruel and foul.’

Roger coloured at his words, but would not be cowed. ‘Is it, though? Are you so very sure, that it cannot be witchcraft? When will you admit, that there is something in this case your physic and your science cannot yet explain, and recognize the evidence right before your eyes? Do not pretend you did not see it too. I know you did.’

‘What evidence?’ asked Hew.

‘Aye, tell him,’ Roger urged.

‘Roger here believes he has the cunning of a surgeon, when he has been employed by one no more than seven months. That is not so strange. For when he was a student here, he knew himself to be so fully a philosopher, he did not need to trouble taking his degree,’ Giles remarked, evasively.

‘What evidence?’ said Hew, again, until his friend replied. ‘As I understand, he is referring to the fact that the incision seems too deep. The vein was severed through. It is Roger’s contention, that if his master’s blade had buried in so far, the wound could not be stopped, and John Blair would have died of it, statim, there and then.’

‘And is there any truth to it?’ It was rare enough that Giles was unequivocal, and it was clear to Hew that he was not so now. His antipathy to Roger made manifest, perhaps, his own internal doubt.

Giles answered honestly. ‘It is, to be sure, an exaggeration. A man may cut his arm off, and survive, with proper care. But, I will confess, it gave me some concern. I come to the conclusion, that John Blair’s exertions on the night he died caused the vein to tear, severing completely the place that had been cut. Roger is correct that it does not satisfy, and yet it seems to me the only explanation. The fatal error was in bloodletting at all.’

‘It is not an explanation,’ Roger argued, ‘that has any credence, more than witchcraft does. You will not deny, whatever else you think of me, that I am an expert in using knives on flesh, from long years of experiment.’

‘That is true enough.’ Hew supported him.

‘Therefore, I ken its properties. Am I not to judge, how the thing was done? And I would chance my life, my master had no hand in that savage piece of butchery. That was not his work.’

‘The pity then,’ said Giles, and the sadness in his voice revealed no relish for the argument, ‘is that he says it was.’ And Roger had no answer to this final word.

‘Well,’ reflected Hew, ‘whatever is the cause, I think that I must talk to Ann Balfour. For if the boy accused her for a witch, then it must be proved, or the rumour quelled, before it can take hold. I will call on her tomorrow.’

Giles consented, ‘Aye, it grieves me that you must. Be conscious of her age, and gentle with her, Hew. Meanwhile, you should go to see the candlemaker’s wife. The body has been taken to their house, which is on the North Street very close to here. She is most indignant at her husband’s death, for which she holds the surgeon firmly to account. I telt her we were looking into it most properly, and you would likely come by to investigate. Which seemed to ease her mind.’

‘Then I shall go now, before I leave for home.’

‘Will you not come, first, to talk to Sam?’ Roger begged. ‘Allow him the chance, the better to explain himself. Or else you will have her damn a man unheard.’

‘Tsk,’ objected Giles. ‘We will not have that.’

But Hew responded coldly; he needed to be certain Roger understood. ‘I will talk to him. But you should be aware, whatever happens next is likely to have consequence. There is no turning back, if you do not like the truth. I cannot promise things will turn out well for Sam. They may well be worse.’

The surgeon’s house was situated in the Market Street, conveniently close to the apothecary. A small consulting chamber opened to the street, scarcely out of place among the other shops, where the nature of its business was exposed to public scrutiny, and passers-by could judge the surgeon by his wares. Here, a man might watch the pulling out of teeth, and in the balmy shadows of an afternoon in spring, when the wind was warm and the weather temperate, a crowd would form outside, spilling down the street, for the pleasures of phlebotomy. On fair days, it surpassed all other entertainments.

It was in this chamber Roger had left Hew, while he went inside to fetch the barber-surgeon. The house behind was small, a single room in width. Roger slept above, in a narrow loft, a modest home enough for a man to lose, when all his future hopes had been invested there. The chamber now was dark, the shutters closed defensively against the craning street. Roger had left Hew the light of a lantern, and its shadows lit upon the metal glow of instruments, stacked upon shelves and hanging from the wall. The box chair, disconcertingly, was bound with leather straps. It was not a place where Hew could find comfort, with or without the presence of the surgeon, and he jumped a little at the opening of the door. There he saw not Sam, but Isabel, his wife.

She was loosely, but modestly, dressed, in a grey kirtle and gown, and a little lace cap, to cover her hair. In the light of the lantern she looked very pale. Her voice, when she spoke, was serious and strained. ‘Roger says that you have come to help. How I wish you could. But my husband will not talk to you. It is hopeless, I fear.’

‘Come,’ he encouraged her, ‘nothing can be hopeless. What has he told you?’

‘That he is responsible for a poor man’s death, and fears that he may hang for it.’

Could it come to that? Hew believed it could. For surgeons had been hanged for recklessness before, where they endangered life. ‘He telt you he felt himself to blame for it? Did he tell you why?’

‘He will not say, at all. And reason cannot move him to confide.’

From above them came the cry, tremulous and shrill, of an infant child. Unconsciously, her hand was drawn towards her breast. ‘That is my bairn. I must go.’

‘You have a new-born child?’

‘She is ten days old. I should not have come, to show myself to you. I have not been kirked.’ The taint of her childbirth was fresh still upon her, she meant. She had not been cleansed. She smiled at him. ‘This day is Candlemas, the feast of the purification. I find that sad, and strange. But we do not count it now.’

It occurred to Hew that Roger had arranged for this. He did not reappear. But doubtless, he had hoped to provoke Hew into pity for the surgeon’s wife. If that was his intention, he had calculated well. For Hew could not dispute that the design had worked.

He told himself the candlemaker also had a wife, and reset the balance, calling on her next. She had rebounded from the horror of her husband’s death with a strange resilience. ‘I expect,’ she said, ‘that ye have come to see himself.’

He echoed her, ‘Himself?’

‘My husband, Jock,’ she returned complacently, ‘in the nether hall.’

‘I saw him at the shop.’ And that had been enough. He would not look again.

‘Aye, not like this. Come away and see. It will ease your mind.’ She took him by the hand, as though he were a child, and led him to a room at the back of the house, where the candlemaker lay, flat upon a board, with a strange, seraphic wonder staring from his face. His cheeks were soft and plump, coloured with red lead, and his hair was tinted yellow, neatly trimmed and combed. He was stripped of his clothes, but his nakedness was bound in acres of white cloth, sprinkled with fresh herbs.

He asked her, ‘Did you wash him yourself?’

‘Why would I not?’ There was fondness in her smile. ‘Would you have me leave him to a stranger?

‘No, by no means. But it must have been hard for you.’

‘Not hard at all. Look at him, now. Handsome is he not? He was a stubborn man, and not, some wid say, an awfy pliant one. But he bent, good as gold, quiet as a lamb. And never did I see a more bonny- looking corpse.’

Bonny though he was, Hew could not stomach Jock for long, and he edged her back into the other room. There she was boiling something greasy in a pot. It was all, she declared, Sam Sturrock’s fault. ‘He never should have opened up that vein.’

‘Did you advise your husband against it?’

‘Advise?’ She laughed at that. ‘There was no advising, wi’ Jock. He wasna one for advice. And he would not be turned, from where he set his mind. His headaches plagued him cruel, and he got it in his head that the cure was letting blood. I cannot tell you why. But it was the surgeon’s job to free him of the fallacy, if that is what it was. Wha should ken but he?’

‘Were you in the crackling house, on the day he died?’ he asked.

‘For a while, I was. Then he sent me hame, for to make the soap. We did not rub along, together in the shop. I do not like the stew. He said I did things wrong. I had a thought, to put a drop of perfume in the tallow, so to scent it sweet. Jock said it was daft.’

’Perhaps you could try it, now that he is gone?’

She was pleased with that. ‘Mebbe, then, I will. I am going now, to give a hand to Eck. He has orders to fill.’

‘But what of your husband?’ Hew wondered.

‘He will not gainsay it,’ she said.

Frances, sitting shadowed in the warm light of the fire, had a kind of glow to her, that served to reassure Hew of her spark and strength. And there was nothing in the least about her petted or indulged, for when he told her that he had not brought the candles, she cried out at once, he should not spare a thought to fret upon her foolishness, which made him wish he had them, all the same. Instead, he brought her wine, and sweet white almond cakes, and settled by her side he told to her the story of the candlemaker, while she listened carefully, and did not turn her face from his until the tale was done. And he could not imagine a world where coming from the cold to sit before the fire he should not find her there, and share with her the weight of matter on his mind.

When he paused at last, she said, ‘A new-born infant, too. I cannot help but feel for them.’

It sobered him to hear her light at once on that. He had not, deliberately, skewed the tale to Sam. But then, he considered, it was natural enough, that the surgeon’s circumstances played upon her sympathy. Had they coloured his?

‘And tomorrow,’ she had smiled, ‘you must go to see the witch. I wish you would be careful, Hew. For I should not like it if she cast a charm on you.’

He rode west towards the Poffle at Strathkinness, until he came to a dilapidated farmhouse, nestled in a clearing in a copse of trees. Outside in the yard, a female of great age drew water from the well, while her ancient counterpart split firewood into logs, a test of strength and vigour for which both were ill equipped. The old man left his work as soon as Hew approached, but buckled at the knees, and could not straighten up. ‘Can I help you, sir?’

Hew asked if he might speak with the mistress of the house, on business that concerned her and the candlemaker. The woman was despatched to take the message in, while the old man offered stabling for his horse, which comfort was a fencepost, where the mare was tethered, in a thistle patch. Hew occupied his time in filling up the guid wife’s buckets from the well, to her man’s disgust. ‘You will mak her soft.’

The woman reappeared, to whisper an instruction in the old man’s ear. She gazed upon the buckets with a blank astonishment, fearful of the magic that had taken place. The old man shuffled off, and beckoned Hew to follow, entering the house. Hew found himself inside a dark-oak coloured hall, a single draughty chamber partitioned at one end to form a sleeping place. The furnishings were sombre, heavy and ornate, and held within their finery an odour of decay. In a pewter chandler, and in sockets round the wall, a score of tallow candles lit among the dust yellowed to obscurity the fleeting strains of daylight, spilling out a sweaty, faintly fetid smell. Beyond them clung the last notes of a heavy kind of perfume, darkly sweet and sinuous. He felt its tendrils quiver, fragile, in the air.

The old man said a word to someone in the room. He motioned to a figure sitting by the fire, and quietly withdrew. And presently Hew heard, distant in the fog, the splintering of wood as he went about his work.

‘Have you brought the candles that are owing to me still? The ones you sent were foul,’ spoke the figure by the fire. Her voice was high and fine, and quavered clear and light like a hollow reed sharpened to a quill, a delicate thin flute. It had a foreign tone to it, that savoured of antiquity.

Hew responded, ‘Madam, I am not the candlemaker.’

‘I hear that from your voice. Nor are you his boy. Then my servant Adam has been caught in a deception.’ She reached out to the hearth place, where was set a bell.

Hew countered hurriedly, ‘I think your servant Adam has not understood. There was no attempt nor intention to deceive. My name is Hew Cullan, and I am come to ask some questions, concerning the man who sold to you your candles. I make no claim to be that man himself.’

‘Then it is more likely Adam has misheard. He has grown quite deaf. Come to me, close. For you will apprehend I cannot see you well.’