Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: The Hew Cullan Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

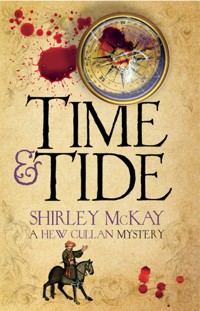

1582, St Andrews. A violent storm wrecks a ship nearby, and the only man about dies without revealing how he came to be there alone, or where the ship was headed. But neither he nor the wreck is really of interest to the townsfolk of St Andrews. Lashed to the deck of the ship is a windmill, a much-needed innovation for the town, but one which soon brings devestation as squabbling over its ownership breaks out. Tasked with tracing the ship to its source, reluctant lawyer Hew Cullan embarks on a journey that will take him far from the security of home and family to Ghent, in the war-torn Low Countries. But are the truth and tragedy surrounding the windmill's real owner – and the death's connected to it – closer to home than Hew could ever imagine? Time & Tide is the third Hew Cullan mystery by Shirley McKay.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 519

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Time & Tide

Shirley McKay was born in Tynemouth but now lives with her family in Fife. At the age of fifteen she won the Young Observer playwriting competition, her play being performed at the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs. She went on to study English and Linguistics at the University of St Andrews before attending Durham University for postgraduate study in Romantic and seventeenth-century prose. An early treatment for her first novel Hue & Cry was shortlisted for the CWA Debut Dagger. Her second novel, Fate & Fortune was published in 2010. Time & Tide is the third Hew Cullan Mystery.

This ebook edition published in 2011 byBirlinn LimitedWest Newington HouseNewington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2011 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © Shirley McKay 2011

The moral right of Shirley McKay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ebook ISBN: 978-0-85790-043-2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Table of Contents

Acknowledgement

Prologue

Chapter 1. An Ill Wind

Chapter 2. The Hidden Catch

Chapter 3. A Miller’s Tale

Chapter 4. The Drowned Man

Chapter 5. Sisters in Arms

Chapter 6. A Glass Perspective

Chapter 7. The Dolfin

Chapter 8. Copin

Chapter 9. Big Fish

Chapter 10. A Miller and his Son

Chapter 11. A Dry Drowning

Chapter 12. Kenly Mill

Chapter 13. Ignis Sacer

Chapter 14. A Wrong Foot

Chapter 15. In the Body of the Kirk

Chapter 16. A Gift Horse

Chapter 17. Mal de Mer

Chapter 18. A Man for Hire

Chapter 19. De Windmolen

Chapter 20. Soldiers of Fortune

Chapter 21. The Spinsters of Ghent

Chapter 22. A Changed Man

Chapter 23. The Flemish Miller’s Gift

Chapter 24. A Beating Heart

Chapter 25. A Welshman’s Hose

Also Available

Acknowledgement

With grateful acknowledgement to James Watson of Culross, the Scotland–Veere Organisation, Esther van Engelen of the Romantik Auberge de Campveerse Toren (open as an inn for the last 500 years); and especially to Peter Blom, municipal archivist of Veere and Paul Veenhuijzen of Earlshall, for keeping alive the spirit of the old entente.

Thanking thame maist hertfullie of their gude ancient lufe . . . Beseking thame that they will continew thair gude will towart us . . . the maist mutual ancient lufing affection quhilkis we haif born aither towartis utheris of auld tymes.

Campfeir [to] the gude tounes of Scotland, 1578

Prologue

St Andrews, ScotlandOctober 1582

Before he learned his letters, Jacob read the wind. He could not recall a time when its patterns made no sense to him, clearer than his catechism, whispered as a child.

– What is thy only comfort, in life and in death?

– That I, with body and soul, both in life and in death, am not my own.

Jacob read the wind, and cursed it when it dropped to lank and irksome stillness. When it turned against him, he was unprepared. It was not as if he had not understood. He knew precisely what this wind required of him, yet he could not rise to it. The waters came at last to blast upon the quietness, and Jacob knew, for certain, he was not his own.

– I am not my own, but belong to my saviour, the Lord Jesus Christ.

He had no hope of Christ in the bowels of the black ocean. It caught the little bark and tossed it like a winnower, blowing dust and thundering, threshing out the storm.

Joachim had been the last to die. He had died before the storm broke. And Jacob had stitched Joachim into a folded sheet of sailcloth, weighed down with lead shot, before tipping the dead boy into the sea. Jacob’s hands were thick and woolly, like a pair of gloves. He had struggled to sew up the seam. It was a blessing that the boy had died before the storm. Jacob saw his mother still, weeping by the river Leie in Ghent. He knew the family well, and had given her his handkerchief. But Joachim’s mind had turned, like all the rest. Jacob had restrained him in the hold, and all through the night had listened to his howls. The pity was it was not Joachim’s fault. Jacob had allowed the boy to gorge himself on sweetmeats, leavening his last hours with the captain’s bread. He heard him howling still, though Joachim had been dead for several days.

Jacob had acquired the captain’s cabin, where he wrote to Beatrix after Joachim died. It took a little time, but he had time enough. Tell Joachim’s mother that, he wrote, and crossed it out. He knew that Beatrix would make sure that Lotte learned to read, and so he wrote the child a letter of her own, and sealed them both with wax from the captain’s candle stub. He found a wooden pepper pot, and placed the scripts inside, together with his book. The letter of its creed he had by heart. He let the candle drip to make it tight around the bung, carving the direction on the surface with his pocketknife, Beatrix van der Straeten, begijnhof sint Elisabeth te Gent. He considered for a moment whether he should set the casket on the open sea, or keep it in the stronghold of the ship, closed in the ocean’s grasp. In the end, he kept it there, knowing it was all the same. He placed it in the captain’s kist among the listless instruments, and lying on the captain’s blanket, Jacob closed his eyes. Better to die quiet, and the ship might let him shelter for a while. He thought of Joachim sleeping on the seabed, where the little fish swam silver through the slack seams of his shroud, making streams of water from his eyes. He thought of Beatrix, fearless, with no breath of hope. He cursed the airless ocean, weeping for the sands. Yet when the wind picked up, he was not prepared for it. He climbed up on the half deck and cried out, choked and raging, not ready yet to yield so easily to death.

Jacob found the wheel, with little hope of turning it. Tobias was dead, and Jacob on his own could not hope to guide the vessel through the storm. Though he read the wind as clearly as a book, he had never been a mariner. He could not take in the spret sail, lower the foresail, bear up the helm or haul the tack aboard, or any of the things he had heard the first mate cry. He no longer felt his fingers in the wrenching wind. Vast waters bellowed, engulfing the deck, and Jacob was knocked from his feet. He clung to the mizzen mast, sodden and blind. He could neither veer nor steer her, rocking through the storm. She was cradled in a trough, where she drank in sheets of water, lapping up from either side. Jacob, drenched and sobbing, sought to scoop them out. He could not clear the decks as fast as she could fill them; and so at last he climbed, exhausted, to the stern, preferring not to drown inside the body of the ship. Yet he found he could not drop into the blackness of the sea. He turned the wheel again, and prayed his old adversary the wind to be a little kind to him. And for a moment, God – or was it yet the wind? – appeared to hear his prayer; the hull began to roll and the fickle gusts rebounded, taking up the sail. The ship was blasted on the waves and blown about its course, with a sudden list and lurching that washed the water out. Jacob gave thanks; to God, after all. And it was Christ his saviour, as Jacob understood, who lit the castle ramparts shadowed on the rock. Far off in the distance, he was coming in to land.

It took a while before he realised what the shadows meant. He came to shallow waters, in the darkness of the storm. The landing craft had long ago been lowered to the sea. Before the early fishermen set out to cast their lines, Jacob would be washed up on the strand, wrung out in the wreckage of the ship. He belonged to his saviour, the Lord Jesus Christ, for he had no spirit left in him to fight. He looked back at the mizzen mast, and felt it sag and spring. The bark began to fracture as she bore down on the rocks. And then he saw his cargo, braced above the hold, and understood at last what he should do. He found her fixed and fast, unflustered by the wind, though high above her flank the topsails flapped and furled. Jacob crept inside to listen for the crack.

And she was still and dark inside, quite dry, and so familiar in her warmth that when he closed his eyes he almost could forget the lurching of the ship, the howling of the wind he had often sought for her. And though she yawned and creaked a little, still she did not stir. She smelled of grease and timmermen when Jacob closed his eyes, so that when at last it came he almost did not mind.

Chapter 1

An Ill Wind

The twa extraordinar professouris affirmis . . . they ar not subject to live collegialiter to eat and ly within the college.

Commission of Enquiry, St Andrews University, 1588

Hew Cullan kicked aside the broken slates as he turned briskly through the entrance to St Salvator’s, his hat and gown dishevelled in the wind. He crossed the college courtyard and hurried to the hall, setting straight his cap. He was, he was aware, a little late; and yet he knew the hall would wait for him. The scholars rose expectantly to see him take his place. They would have gaped like louns to catch him at the chase, darting through the tennis courts in primrose-stirruped slops. Masters, they well knew, could have no other lives.

And for the regents in their midst, who had the daily care and teaching of these boys, this was true enough, reflected Hew. His own place was a sinecure: magister extraordinar in law, in a college that could boast no legal faculty. He played little part in its domestic life or discipline. The appointment of professors in the laws and mathematics had left no impression on the core curriculum, grounded in philosophy and arts. Hew gave lectures to the college once or twice a year. As second master, he was sometimes called on to officiate, in the absence of the principal, anatomist Giles Locke. When, as often happened, they were both engaged, on some more pressing business of the Crown, the third professor, grumbling gently, set aside his sums to step in to the breach.

This third professor, standing at Hew’s side, reached across to nudge him, breaking through his dreams. He plucked a withered fragment from Hew’s sleeve. ‘Acer maius, or, to many, platanus,’ he commented. ‘The greater maple, commonly, and falsely, called the plane tree or the sycamore.’ The mathematician opened out his palm, showing Hew the seed, the winged fruit of the sycamore. ‘You are sprouting wings. What as a bairn I chased round dizzy in the wind. We called them locks and keys, or whirlijacks.’

Hew suppressed a smile, which old Professor Groat, with his rheumy, washed-out eyes, was quick enough to see. ‘I understand you well. You do not think that I could ever be a child; or else this fledging plane tree harks back to the ark.’

‘Ah, no, not at all,’ protested Hew, who had indeed been thinking something of the sort. How old, after all, was Bartholomew Groat? Sixty years? Eighty? Or, as Giles asserted, nearer fifty-three, of phlegmatic disposition, prone to windy gout.

The professor blew his nose. ‘Tis true enough, that when I was a boy this maple was a novelty, which now is thought a scourge, and counted as a weed.’

He did not give up the seed, but wrapped it in his handkerchief to put it in his pocket; whether to preserve the ghost of little Bartie Groat, giddy as the wind, or to prevent its spread, Hew could not be sure. ‘The winds were wild last night,’ he remarked more diplomatically.

This observation had a sobering effect. ‘Foul spirits stir up tempests,’ Groat imparted gloomily. ‘The milk kine startled in the fields, the storm has soured the milk. The priory trees are torn up by their roots; the shore mill lade is flooded. Tis providential, Hew.’

‘Stuff and superstition,’ Hew retorted. ‘I do not believe in it.’

Bartie cast his eyes to heaven, sending up a prayer. ‘The young are always quick to scorn. And yet the wind has one effect that cannot fail to move you. I heard there was a ship wrecked in the bay. All the crew were lost.’

‘Dear God, rest them!’ whispered Hew. ‘Were the poor men Scots?’

‘Zeelanders or Flemish, judging from the load. I wonder that you did not see it, on your way to town,’ murmured Bartie Groat.

Hew shook his head. ‘I lay at the West Port last night,’ he explained. ‘My horse does not care for the wind.’ Dun Scottis cared for little that upset his regimen. He baulked at wind and water, with perfect equilibrium.

‘You ought to take up lodgings, as I’ve said before. I confess myself perplexed that you will not consider it,’ Bartie answered peevishly.

It was a well-worn argument, and one to which Hew struggled to respond. He had declined the rooms that came with his election, preferring to remain at home at Kenly Green. The house stood four miles south, an hour on foot upon a winter’s day, and a little less in summer, on his sluggish horse. Returning to the college for a second year, he already felt the cloisters closing in, the hallowed kirk and walkways a conspiracy of spires. It was not a feeling he could share with Bartie Groat, who took his dinners daily at the college mess, and brightened when the cook doled out a second slop of neaps. Hew did not care to end his days collegialiter. He changed the subject quickly. ‘I see the doors have closed. So we are all assembled, and ready to begin.’

One by one, the names were called, and the students swore allegiance to the university. The youngest scholar stumbled at the stand. In awe at the proceedings, he clean forgot his oath. Hew Cullan winked at him, and saw the boy’s astonishment collapse into a grin. A regent hurried forward and retreated with his charge, who, to Hew’s amusement, was named as George Buchanan. He saw nothing in the boy that stuck him as remarkable. It seemed unlikely that their paths would cross again.

Bartie had withdrawn, like a tortoise to his shell, where for the last half hour he had appeared to be asleep. When Hew was least expecting it, he blinked, thrusting out: ‘It is not like our principal to miss matriculation.’

Hew answered stiffly, ‘Indeed, not.’ He cursed both God and Bartie Groat. In a few more minutes’ time, enrolment would be done, and he could take his worries out into the street. For now, he must stay resolute, civil and in place. He did his best to look discouraging.

‘Perhaps he has been called out to a patient,’ Bartie droned, relentlessly. Giles was a physician, as well as an anatomist, with a thriving practice in the town.

‘Aye, perhaps.’

‘Or on business of the Crown.’

‘Tis very likely,’ Hew agreed.

‘Though on business of the Crown, you also are most frequently invoked. Therefore it may be inferred, since you are here, and he is not, it is not business of the Crown.’

Groat was penetrating, gazing once again with his colourless, damp eyes, no less clear and piercing through the film of age. Hew saw no escape. The ceremony drawing to a close, the boys were ushered out, to lecture rooms and lodging houses. Hew was left behind with Professor Groat. He did not dislike the man. Groat was a fine astronomer, and lyrical upon the motions of the spheres. But he remained inclined to gloom, his prognostics seldom ending happily. On this subject, at this time, Hew had no wish to talk to him.

‘His young wife is with child, of course,’ Bartie reached his pinnacle.

‘She is,’ admitted Hew.

‘Pray pardon – I had quite forgotten – he is married to your sister, is he not? Who has the falling sickness?’

‘I commend you on your powers of recollection,’ Hew returned abruptly.

Groat persisted, undeterred. ‘Doubtless, there are dangers there. Please tell Giles, they are in my prayers.’

‘Doubtless, he will thank you. I will tell him straight away.’

Professor Groat was right. It was unthinkable that Giles would miss matriculation, without a word of explanation or apology to Hew. If he was not in college, then he must be at home, and if he was at home, that could only mean one thing. Hew abandoned Bartie at the door and hurried down the North Street towards the Fisher Gait.

The streets beyond the college were deserted, as though the wind had swept them clear, and left behind its footprints in a scattering of leaves. The fisherwives had dropped their cries of codlings and late crabs, their empty crates and buckets littering the steps. A bare-legged child stood watchman, rushing at the gulls. Hew called out in passing, ‘Are the markets done? The clock has just struck twelve.’

The child stopped to consider this, sucking on a thumb. It offered up at last, ‘All gaun, tae the wreck.’

‘And left you on your own? Good bairn,’ Hew answered vaguely. He could not discern, from the whisper thick with thumb, whether he was talking to a girl or boy. He found himself unsettled by the queerness of the child, and by the empty thoroughfares that led to the cathedral, the town and markets suddenly bereft, upended by the storm. He hurried past the fishing quarter to the castle on its rock, towards the little house that overlooked the cliff. The wind had dropped back, the sea a sheet of glass, where a hazy sunshine skittered, bouncing back and lighting up the stones.

The house was battened fast against the wind and sunlight, doors and shutters closed. Hew’s knock was answered by the servant, Paul. ‘I kent it was yersel’,’ he yawned, ‘by dint of a’ the din. The master is asleep. I’ll tell him that you called.’

‘How so, asleep? Has your mistress had her child?’ demanded Hew.

‘She hasna’ started with her labours yet. No doubt you will be telt, when her time is due.’ The servant had retreated, pulling back the door. Hew stopped it with his foot. ‘I think you know me better, Paul,’ he warned. ‘Since I am not the blacksmith, nor the barker with his bill, you do not close the door to me. It seems you have forgotten it.’

The reprimand struck home. Paul began to stutter and to blush. ‘Tis only that . . . your pardon, sir, but do not tell the doctor. He is fair forfochten.’

‘Do not tell him what?’ a sleepy voice inquired, and Giles himself came rumbling through the hall, squinting at the light. ‘If that is Master Hew, then bid him wait until I’m dressed.’

‘By your leave,’ muttered Hew to the servant, who allowed him to pass with a hiss. ‘Do not say, sir, that I did not prepare you.’

‘Prepare me for what?’ Hew hissed back.

‘Why is it so dark in here?’ Giles had opened up the shutters, letting in the air, and blinking as the sunlight filtered through the room. ‘How comes the sun so bright?’ he pondered paradoxically.

‘How comes it that your household is asleep?’ retorted Hew.

‘I know not . . . What? What time is it?’ Giles rubbed his eyes.

Paul answered, disingenuously, ‘Mebbe eight, or nine? I cannot rightly say, for I havna’ heard the clock.’

‘It is a little after twelve,’ corrected Hew. ‘And yet it is no matter, Giles.’

Giles looked baffled, like a man disturbed from walking in his sleep, to find out he has trodden on his spectacles. ‘Of course it matters!’ He made sense of it at last. ‘I have missed matriculation.’

‘No matter, that,’ said Hew. ‘Professor Groat and I have managed it between us. And save for my solicitude, and Bartie’s speculation, we managed it quite well.’

‘I’ve no doubt that you managed it,’ protested Giles. ‘That is not the point. The point is in the principle; that is, I am the principal. Did I not tell you to wake me?’ he rounded on Paul. ‘Did I not tell you, expressly?’

The servant stood his ground. ‘I do not recall it, sir. Now, I was looking for your hat, when Master Hew came chappin’ at the door; I’ll go and find it now, and by your leave. I doubt you must have left it at the college.’ He slunk off down the passage, with a backward glance at Hew, which plainly spoke, ‘You stirred it; now you settle it.’

Giles looked hopelessly at Hew. ‘Much good my hat will do me now! I must be severe with him, for he has gone too far. He always goes too far. Does he? Has he? Has he gone too far?’ he flustered.

‘He does, and has, and always goes too far,’ acknowledged Hew. ‘And yet, on this occasion, he must be commended, for clearly he holds your best interests at heart.’

The doctor groaned. ‘Then he is above himself, and ought to be dismissed!’

‘I cannot think that that will help. What is the matter, Giles? This is not like you,’ said Hew.

‘I am not quite myself,’ admitted Giles. ‘My world stands on its end. It is the helter-skelter of a dizzy heart.’

‘Indeed, that does sound serious,’ Hew answered with a smile.

‘It is serious. The matter is your sister Meg. She spent last night in thrall to the falling sickness.’

‘I feared it,’ Hew exclaimed, ‘though am loath to hear it. How does she now?’

‘Sleeping like a child. The worst of it has passed; the nurse has come to sit with her. I closed my eyes a moment . . .’

‘Then Paul is right and I am to be blamed for waking you,’ Hew declared emphatically. ‘The crisis point is over, rest assured.’

‘Rest assured?’ Giles cried. ‘If I could rest assured . . .! I am helpless to help her, Hew. Helpless.’

It was the closest he had come to frank despair, and Hew felt at a loss. ‘You are too much in the dark,’ he tried at last, ‘and want a little sun, to show this prospect in a fairer light. Come, then, walk with me. The air will do you good.’

The doctor shook his head. ‘I cannot leave the house.’

‘And yet, a moment past, you were all for setting out, to see the boys matriculate,’ Hew reminded him. ‘You are disordered, Giles, and have lost your balance. Come, I insist. We’ll keep the house in sight.’

They settled on the path above the castle beach, and walked along the cliff top to the summit of Kirk Hill, that led down to the harbour and the shore.

‘I am right sorry,’ ventured Hew at last, ‘to hear that Meg has taken fits again, at this close stage of her confinement. I cannot comprehend it, for I thought the sickness well controlled.’

‘For that,’ Giles returned, ‘you had not reckoned with the wind.’

‘What has the wind to do with it? You sound like Bartie Groat!’ objected Hew.

Giles looked small and cowed in the shadow of the cliffs, his towering bulk diminished by the water and the sky. ‘Do you not see it?’ he urged.

Hew resisted stubbornly. ‘I do not see at all.’

‘Then I shall explain it,’ Giles answered with a sigh. ‘You are my dearest friend, and know me well enough to know I do not sink to superstition, like Professor Groat.’

‘I thank God for that,’ snorted Hew.

‘And yet it is a fact that the wind effects disturbances,’ the doctor went on earnestly. ‘It sets the world on edge. The master at the lector-schule remarks it in his bairns, running wild and shrieking when the gusts blow high. It has no less effect upon your sister Meg, and one well fraught with danger, in agitating sickness, and precipitating fits. I can no more control it than the raging seas.

‘The sailors with their quadrants cannot make the compass of the ocean’s toss and turn, where chance clouds overlap the constant flux of tides. We draw the moon and oceans, the heavens and the stars, and shape their folds of darkness to our little worlds, yet for all our charts, we cannot map the surface of one fragment of the whole. We think ourselves ay at the centre, at its very heart, that somehow we have harnessed nature, bending wind and water to our will, yet all the while we are as nothing, specks and motes caught in the breeze, that nature taunts and tosses like the frigate in a storm.’

‘I know you do not think that,’ remonstrated Hew, ‘who own the finest sets of instruments that I have ever seen.’

‘They are but trinkets, toys. I thought to make a horoscope!’ Giles contested bitterly, ‘But think of that! I thought to mark his coming on a chart. And would that smooth his passage, do you think? Would such calculations help the bairn?’

‘Well, I do confess, I have never made much sense of your prognostications; I make a poor astronomer,’ reflected Hew. ‘Yet I will affirm your measure over nature, your medicine and your physic over its disease. As I have seen Meg, with her potions and simples, mop out corruptions and clear up the cough.’

‘Meg is a special case,’ conceded Giles. ‘She turns nature in upon itself, and bends it to her will. Then nature is become an art, and sickness makes the cure.’

‘Well then, trust in her. She proves it can be done. And when your courage fails you, put your trust in God.’

‘Amen to that.’ The doctor fumbled in his pockets, drawing out a string of beads. Awkwardly, Hew turned away, allowing Giles the quietness of prayer. He watched a young girl clamber over rocks, throwing pebbles on the beach below. The girl glanced up and caught his eye. Then, to his astonishment, she ran across the sand to turn a perfect cartwheel, white limbs whirling naked in the shadow of Kirk Hill.

‘Look there!’ Hew exclaimed. ‘And you might find your thesis proved: the world turns upside down!’

Giles looked up and frowned. He slipped the rosary into his pocket. ‘That is Lilias Begg, who should not be out alone. She is an innocent; a natural fool. The louns unkindly cry her, daft quene of the shore. Come up, Lilias Begg!’ he called out to the child, while Hew gave thanks to God for the distraction.

The girl smoothed down her dress, and climbed the steps carved in the cliff, her bare legs flecked with sand.

‘If she is seen as lewd and loose, the kirk will hold her mother to account,’ Giles asserted anxiously.

Hew objected, ‘Surely, she is just a child!’

‘She is seventeen. Lilias Begg!’ Giles called out again, ‘Where is your mother? Does she know you’re gone?’

‘You do not need to shout,’ said Lilias sweetly. ‘For, I am here.’

She turned a somersault. ‘I can coup the lundie,’ she announced.

‘So I see,’ Giles tutted. ‘Lilias Begg, this will not do.’

Lilias Begg had skin like milk, paler than a swaddling bairn’s, that never saw the sun. She had brittle, flaxen hair, fairer than the smallest child’s, and fey, elfin features, like a faun from faerie land. She stared at Hew with solemn eyes, and did not return his smile.

‘Where on earth has she come from?’ Hew whispered to Giles.

‘She is the daughter of Maude Benet, that keeps the haven inn, and of Ranald Begg. A drunkard and a sot,’ Giles declared contemptuously. ‘He drank himself into an early grave, and left the world a better place once he had gone to Hell. He beat Maude Benet senseless, when she was with child. For which he put a shilling in the poor box, and escaped a fortnight in the jougs.’

It was rare for Giles to speak so unequivocally, and rarer still to hear him damn a man. The damage to an unborn child had cut the doctor deep. Nonetheless, he qualified, ‘Or so I have been told.’

Lilias said suddenly, ‘I am the whirlijack.’

‘And what is that?’ demanded Giles.

‘The whirlijack.’ Lilias began to spin like a whirlwind, perilously close to the edge of the cliff.

The doctor caught her hands. ‘Be still; you will dance us all giddy! Whatever do you mean?’

‘I am the whirligig, that spins the world.’

‘The seed pods from the sycamore,’ suggested Hew. ‘The leaves and fruits are blown all over town.’

‘Aye, but spins the world?’ Giles fretted. Something had unsettled him, returning him to gloom. He was already looking back towards the house.

Lilias said helpfully, ‘It came here on a ship.’

‘Some trinket she has picked up at a fair,’ Doctor Locke concluded. ‘A trick to catch the wind. This is Master Hew,’ he turned again to Lilias, ‘who will take you home.’

Hew spluttered, ‘I will what?’

‘Tis plain enough,’ insisted Giles. ‘She will not go alone.’

‘Ah, but surely, Paul . . .’ said Hew.

‘Paul would prove no match for her,’ Giles argued. ‘For all she is an innocent, she’s cunning, in her way. She will lead a man a dance if he allows her to. Now she has come of age, it is her natural instinct. If Lilias is taken by a man, then it must be someone who can give a good account of himself.’

Lilias smiled knowingly. ‘I saw a man, in my Mammie’s bed. I saw a man, and his hands were all black,’ she confided.

‘Dear God!’ muttered Hew. ‘I take your point,’ he said to Giles, ‘though it is scarcely reassuring.’

The doctor hesitated. ‘I would go myself . . .’

‘Peace, I’m on my way. Lilias, take my hand!’ Hew addressed the girl perhaps more brusquely than he had intended, for her lip began to quiver. ‘I want Mistress Meg.’

‘So that is it,’ Giles sighed. ‘Meg has ay been kind to her, and gives her sugar suckets for the cough. I will have some suckets sent to you,’ he promised, ‘but you cannot see her now. Mistress Meg is not well.’

Lilias asked brightly, ‘Will she die?’

Hew said, ‘Hush, for pity’s sake!’ as the girl began to sing, ‘Mistress Meg is dead and gone, poor dead sailors all are gone.’

Giles cleared his throat. ‘No one here is dead and gone. Yet I must leave you to it. In the temporal sense,’ he excused himself to Hew, ‘I have been gone too long.’

‘Aye, for certain, go,’ his friend assured him. ‘I will see her home.’

He turned to Lilias Begg. ‘You are trouble, as I think.’

Lilias smiled. ‘Come see!’ She took his hand and ran, down Kirk Heugh and through the harbour, turning south along the shore, past the priory and the Sea Port, past the fishing boats and mill. The boatmen stared at Hew, in his scholar’s drabs. ‘This is not the way,’ he panted, ‘to your mother’s house.’

Lilias giggled, stopping short. ‘Look! Look there!’ She pointed to the rocks at the far side of the bay at Kinkell Braes, across the damp dark sands, flattened by the ebb and flowing of the sea. The tide was coming in, and a thinly straggled crowd came scrambling up the beach, retreating from the wreck. Four horses were backed up from the bulkhead of the ship, straining at the water’s edge. Lilias stood pointing, laughing in delight, ‘Look! There it is, the whirlijack!’

And there it was, the whirlijack, a perfect wooden windmill, braced against the foremast, high up on the deck. It was painted blue and white, and cross-sailed like the saltire on a summer’s day. And flanking both its sides were ropes and stiff machinery. The town had summoned all its arts in salvaging this toy, bright above the wreckage in St Andrews Bay.

Chapter 2

The Hidden Catch

The crowds receding from the ship had settled in the harbour inn, trailing sand and silt. Some took their dinner with them out onto the pier, which overlooked the wreck, to gossip over bowls of soup and sops. Others crammed round trestle tables in the common hall. The air was sweet with onions, melting into broth, and bitter with the fog of candle light. A tapster lassie flitted to and fro with tankers full of ale, batting back the banter of the drinkers at the bar. Lilias clung tightly to Hew’s hand. ‘Mammie will gie us dennar, ben the hinner house,’ she promised, tugging past the drinkers, through a narrow door.

They came out in the kitchen, where a girl of about fifteen stood squinting at the pottage in a vast iron pot, furrowing the surface with a wooden spoon. The boards were lined with rows of bannocks, yellow slabs of bacon fat and collops of salt beef. An offal pie stood centrepiece, spilling out its gizzards in a scattering of mace. The paunch and udder filling had acquired a greenish tinge.

The young pot stirrer started at the sight of Hew. ‘Where have you been, wee lurdan?’ she confronted Lilias. ‘A’body’s gang speiring for you.’

‘Where’s my Mammie?’ Lilias answered blithely.

‘Doun the ladder.’ The girl retreated to a little hatch, open to the wine cellar. ‘Lillie is come hame,’ she shouted through the floor.

‘Aye, I hear you, Elspet,’ wafted from the vaults. ‘There is no sense in flyting with her, for she does not understand you.’

‘Likely,’ muttered Elspet, ‘she will understand a skelp.’

‘I heard that too,’ the cellar warned. ‘And you ken well enough what I will answer, if I hear you speak it once again. Send Archie down, to help me lug the cask, and gie the bairn her dinner.’

‘Archie isnae up here,’ Elspet called back down.

‘Where is he, then? The louns will drink us dry. I cannot shift they barrels on my own.’

‘He has not come back,’ Elspet replied. ‘But Lilias has fetched up with a paramour.’

Lilias gave an unexpected show of wit, in poking out her tongue at her. Hew removed his cap and gown, and set them neatly on a stool, before rolling up his sleeves.

‘God save us, sir, what are you doing?’ Elspet shrieked.

He answered with a wink, ‘Helping with the cask.’

‘Take it!’ cried the voice. The head and shoulders of a flask of wine emerged above the hatch. Hew knelt down to catch it, and dragged the flagon up onto the earthen floor.

Lilias announced, ‘Tis Mammie!’ as Maude herself appeared, dusting down her skirts, to gaze at Hew appraisingly. ‘I thank you, sir, but who are you?’

‘He is Master Hew!’ Lilias clapped her hands. ‘Come here for his dennar.’

‘I am Hew Cullan, master at St Salvator’s. I brought your daughter home,’ Hew explained. ‘I found her on the cliff beside my sister’s house. My sister is married to Giles Locke.’

‘The doctor? Aye, they are good people,’ Maude approved. ‘Your sister has been kind to her, and Lilias does not forget. She is like the little bird that comes back for its crumbs. Where she takes a liking, she is quickly tamed, and that is rare enough.’

Maude Benet had the look of Lilias, withering with age. Her lightness and fragility had fused to wiry strength, the froth of blonde hair grizzled and grown coarse, the pale skin weathered to a motley red. After years of flyting sailors from their drunken fights, there was little shy or subtle left in Maude. And yet she spoke more gently than the common tapster wife. She had an air of comeliness, and simple commonsense. ‘I thank you for it, sir. She is a silly bairn, that has no understanding. I hope she has not caused you trouble?’ she went on.

‘None at all,’ said Hew. ‘She has been showing me the windmill.’

‘That is some sight, is it no!’ marvelled Maude. ‘The whole town is astuned at it, and it was in the hubble that the lass gave us the slip. It will take something to shift it, right enough.’

Lilias tugged her skirt. ‘Mammie, we are come for dennar!’ she repeated patiently.

Her mother smiled. ‘It is a thing when we must ken our manners from a silly child. Come sir, what will you eat?’

‘Madam, you are kind.’ Hew shook his head emphatically, and moved a little downwind of the udder pie, gently warmed and pungent in the close heat of the fire.

‘I ken what you are thinking, sir,’ intercepted Maude.

He muttered indistinctly, ‘Truly, I hope not.’

‘We will not keep you long,’ Maude went on, oblivious. ‘What is that you do there at the university?’

‘I am a professor,’ Hew admitted, ‘in the civil laws.’

‘You do not say?’ She looked impressed. ‘Yet even a professor must have his dinner hour. Let go the gudeman’s hand,’ – this latter was to Lilias – ‘and he shall have a fish.’

‘I thank you mistress, but I must be gone.’

‘I do not hear you. Elspet, gie the bairn her broth,’ instructed Maude.

Elspet ladled pottage in a bowl, and placed a piece of buttered bannock on the side. Lilias began to cram the bread into her mouth, broth and barley seeping down her chin, while Elspet rolled her eyes, reaching for a cloth.

Lilias whimpered, ‘Master Hew!’

‘The bairn will not be settled, till you have your dinner too,’ her mother pointed out. ‘I pray you, sir, sit down!’

Hew gave in reluctantly, caught between the two, as Maude produced a haddock from a pail. ‘Here he is, fresh from this morning’s boat. You shall have him fried in butter, for he will not keep till fish day.’ She slapped down the fish and slit it with a knife, spilling paunch and pudding on the wooden slab. ‘See how fresh he is! His heart is beating still!’ The sliver sat, still pulsing, in the circle of her palm.

Lilias looked up, ‘I want his beating heart,’ she mumbled, through a mouth of crumbs. Elspet gave a shudder of disgust.

Maude Benet frowned. ‘Why would you want his heart, my pet?’

‘For Gib.’

‘I have telt you, poppet, that your must not feed the cat. For what use is Gib Hunter, if he will not make his dinner on the mice?’ her mother told her fondly.

Lilias set her lip. ‘He likes the fish heart better.’

‘Then he has no business to.’ Maude scraped out the innards of the fish, and scooped the debris up into the pottage pot. Elspet pulled a face. ‘And you need not girn like that,’ her mistress scolded. ‘When were you so proud? Take out the wine and pottage for the baxters.’ Hew felt his stomach lurch as Elspet poked the fish eye to the bottom of a bowl.

‘Your pardon, sir,’ she asked him, passing with the tray, ‘But what are civil laws? Do you teach the lads their manners?’

He smiled at her. ‘Not quite.’

‘A pity, for they want them,’ she retorted.

‘It is the law of persons, not the kirk. But do the students come down here?’ asked Hew.

Maude Benet answered tartly, ‘Aye, it has been known. For they are not so delicate as you.’ She poured oil and butter in a pan, and placed it on the flame. ‘We shall leave it there until it smokes, and you shall have a cup of wine to wash it down. You will not make a better banquet, anywhere in town.’

The pan began to sizzle and the scent of melted butter filled the room. Maude had carved the haddock into four white gleaming fillets, when the kitchen door flew open, and an anxious voice demanded, ‘Is it true, what Elspet said?’

Maude continued with her cooking, unperturbed. ‘James Edie, you are come into our kitchen, not the common drinking room. I doubt you missed your way. If you want the quiet house, then go out in the yard.’

James Edie growled, ‘Why must ye be so hindersome? Ye ken what I’m about. Elspet said the lass ran off, and came back with a man of law? Is it true, sir?’ he appealed to Hew, as to a man, of better sense.

‘You need not answer,’ countered Maude. ‘It is not his business.’

James Edie’s beard and hands were neat and trim, suggesting some clean trade. He wore well-fitting workday clothes, of decent, woollen cloth, in shades of russet, grey and blue that matched his woollen cap, and on his cap a little pin, a wheat sheaf wrought of yellow gold, suggested he did well from it. A baxter, Hew inferred. He put the baxter’s age at forty-three or four, older than Maude Benet by a year or two at most, though more kindly treated by the passing of the years. The little grey that flecked his hair and beard, the few light lines that creased his eyes, had mellowed and improved his looks, and lifted him above the commonplace.

Hew answered, civilly. ‘I am professor at the college, in the civil law. I found Lilias lost, outside the doctor’s house, and brought her home, at his request. My interest in this matter starts and ends there, sir.’

‘Then I am grateful to you.’ James Edie looked relieved. ‘Maude kens well enough, that it is my business, though I wish it were not, if she allows her daughter to run riot through the streets. The kirk will not condone it, for they cannot thole such wantonness.’

‘The bairn does not run wanton in the streets,’ contradicted Maude. ‘No more do I allow her to. She slipped away, this once. You ken yourself what rare events have happened here today.’

‘I grant it, that the day is quite extraordinary. Yet you will admit it happened once before. And if it should again . . .’

‘I swear that it will not,’ said Maude.

‘God keep you to your promise then.’ James Edie glanced about the room, and found another cause for discontent. ‘This bannock is not baxters’ bread,’ he noticed, picking up a loaf.

‘That bannock is for private use,’ said Maude. ‘We do not sell it.’

James Edie tutted. ‘Tell that to Patrick Honeyman, when he demands your penalty.’

‘I will not have to,’ Maude retorted. ‘He will never see it. It is for private use, and in our private kitchen. Out!’

‘Peace, for I am gone! And welcome to your bannock, and to her, for both are hard and coarse!’ James Edie turned to Hew. ‘Yet Maude mistakes my better nature, if she thinks I won’t tell Honeyman.’

‘Your better nature, James, and what is that?’ scoffed Maude. ‘I ken you will not tell him.’

‘Do not count on it. Take care, and keep her safe,’ the baxter warned.

Maude softened. ‘Aye, I hear ye. I will keep her close. We all have been unsettled by the day’s events. She will not wander off again.’

‘Who was that?’ asked Hew, as Edie closed the door.

‘James Edie, the baxter.’

‘Aye, but what to Lilias?’

‘He is some distant cousin of her father,’ Maude explained, ‘my late husband, Ranald Begg. For which he seems to think he has the keeping of her. Some months ago, she strayed out on the street, and was had up by the kirk, for lewd and loose demeanour, as they like to cry it. Wherefore they found her wanting, as a silly bairn, they count the puir lass innocent of shame. James Edie claims they put her in his charge, that he must lock her up, as lunatic and furious, if she is caught again.’

‘Is he her closest agnate?’ questioned Hew.

‘Her closest what?’ gawped Maude.

‘Her nearest kinsman,’ Hew explained, ‘upon her father’s side.’

‘I suppose he is.’

‘Then I am afraid he spoke the truth,’ he told her seriously. ‘For it is his duty and his right to see her locked away, if the kirk requires it.’

‘Truly?’ wondered Maude. ‘I thocht it was a tale he put about, to fright us into thinking that he has some purpose here.’

‘Why would he do that?’

‘No matter. It is like him. Yet, you say, he has the power to lock her up?’

‘More than that, he must, if she offends the kirk. Else he himself must bear the burden of her punishment.’

‘Then I have mebbe misjudged him.’ Maude reflected, ‘for I did not know it. I am in his debt.’

‘I should tell you, perhaps,’ Hew went on, ‘that when I saw your daughter on the beach, she was playing coup the lundie.’

‘What on earth is that?’

Hew floundered for a moment, scuppered by the phrase he had repeated word for word, not knowing what it meant. He was rescued by Elspet, returning with the tray. ‘She was turning somersaults! Bad girl!’ she answered with a grin.

‘And who has taught her that? Elspet, was it you?’ demanded Maude.

‘Mary, more like.’ The girl said self-righteously.

‘I made the whirlijack,’ Lilias translated, scrambling from her cushion. ‘Shall I do it now?’

All three of them cried, ‘No!’

Maude suggested, ‘Go outside with Elspet, and pick parsley for the fish. I see, sir, I do see,’ she said quietly to Hew. ‘I must take better care of her.’ She dropped the fish into the smoking pan, and placed a slice of bannock on a wooden plate.

‘James Edie seems a decent man, at least,’ Hew observed.

‘A decent man,’ repeated Maude. ‘A baxter, and a bailie on the burgh council.’ She grinned, unexpectedly. ‘I’ll tell you a thing I have noticed about baxters: the cleaner their hands, the blacker their bread. James Edie is the exception. His bread is as white as his hands.’

Hew could not tell if she liked the man or not. He suspected, both.

‘Did you see the baxters huddled at the bar?’ Maude continued scornfully. ‘They are having one of their extraordinary meetings, as they cry them.’

‘What, all of them? There must be fifty, sixty, in the gild,’ objected Hew.

Maude conceded, ‘So there are. They hold their convocations on the Gallows Hill. The four of them out there are keepers of the keys. Four locks, four keys; four keys, four men, that no man can unlock the baxters’ box without the cunning of the rest.’

‘And what is in the box?’ asked Hew, amused at this.

‘God knows, biscuit crumbs,’ Maude shrugged. ‘They four are come to batten on the wreck, without a thought for those puir sailors lost. Their eyes are fixed full on yon windmill.’

‘I cannot think they have much hope of having it,’ said Hew.

‘Then plainly, you have not had many dealings with the baxters. Whisht now, here is Lilias coming back with Elspet, who both have wagging tongues. What have you there, my flower?’

‘Marigolds. And parsley, for Master Hew his fish, because he is my friend,’ Lilias said insistently.

Her mother smiled at her. ‘I do believe he is. Now he shall have his haddock.’

Maude lifted out the fish, a translucent, steaming white, and set the fillets on their sops in a foaming butter sauce, freckled with the parsley and a sprinkling of verjuice.

By the time Hew returned to the bar, most of the drinkers were gone. The reclamation had been halted by the tides, and the rest of the town had drifted back to work. The baxters, though, were still entrenched, locked in weary battle lines, of empty stoups and cups. James Edie stumbled, bleary-eyed, to catch him as he passed. ‘Your pardon, and your patience, sir. I hope my business with Maude Benet caused you no offence?’

‘None at all,’ Hew assured him, attempting to inch closer to the door.

‘I have no liking for my charge,’ persisted James. ‘Yet I have been advised it is the law.’

Hew nodded. ‘I explained as much to Maude. I think she understands it.’

‘Then I am obliged to you. Will you have a drink with us?’

‘No. I thank you,’ Hew said firmly. ‘I would not interfere in matters of the gild.’ The baxters had a look of long drawn out campaign, which he was not prepared to join.

‘The baxters’ work is done. We are now convened on business of the town, and would welcome an opinion from the university.’ The man was not so easily repelled. Before Hew could extract himself, he introduced his friends. ‘Our spokesman, Patrick Honeyman, is deacon of the gild, and like myself, a bailie; this is Christie Boyd, town clerk and baxters’ scribe, and this, his brother John.’

Christie had a minute book, in which he scribbled endlessly, scraping with his pen. His brother John was sullen, dour and taciturn. Hew knew the bailie Honeyman by sight, a fleshly man with beetle eyes, burrowed in his cheeks like currants in a bun. His flabby face and hands were scorched from constant close exposure to the fire. The bailies were town councillors, which made James Edie’s offer harder to refuse. There was no love lost between them and the university; the council thought the colleges aloof and supercilious and the colleges in turn found them rude and superficial. Each resented bitterly the interests of the other.

‘I am absent from my college, and in academic dress. I cannot stay to drink,’ Hew hurried to excuse himself. As he had anticipated, refusal caused offence.

‘What is it, then? Too proud?’ bridled Patrick Honeyman. ‘We are not fit for converse, with the un-i-var-sitt-ee!’

The Honeymans were baxters, born and bred. When Hew had first enrolled as a student in St Leonard’s, it had been a Honeyman who baked the college loaves; some elder, poorer cousin to the deacon of the gild. At laureation feasts, or when fights broke out in hall, there was no surer weapon than the Honeyman bread roll. The order had been cancelled when a student lost an eye, and St Leonard’s opted for a lighter bake. It helped explain, perhaps, the baxter’s animosity.

‘It is not pride, bur propriety dictates,’ defended Hew. ‘I must set an example to the students in my charge.’ There was a little truth in his excuse.

The clerk, Christie Boyd, looked up from his notebook, at which he had been scratching all the while. ‘They will not see you, sir,’ he promised confidentially. ‘For all of them are fled, save one who is sequestered in the lassies’ sleeping loft, and dares not show his face till you are gone.’

‘I thank you for the notice, though I wish I had not heard it,’ Hew answered with a groan.

‘Your students are a pestilence, a plague upon the town. I charge you, sir, to flesh him out, that we may see him whipped.’ Honeyman revealed a cheerful prurience, which served to further strengthen Hew’s resolve. ‘His discipline is not my place. Yet I take note of your concern,’ he replied dismissively.

The deacon stared at him. ‘Not your place? Then what, sir, is your purpose here? I ken you, Master Cullan. You are assistant to Giles Locke, who is our town recorder of unnatural deaths. Are you come at Doctor Locke’s request?’

Hew admitted, ‘No . . . and yes . . . I came at his request, but not on business of the town.’

‘I see that you prevaricate. Then let me ask you bluntly, what is your interest in the wreck?’ demanded Honeyman.

‘I have no interest in the wreck, saving for the common one, of pity at the loss of life, and vulgar curiosity,’ asserted Hew.

Honeyman said rudely, ‘I do not believe you, sir.’

‘Do you say I’m lying?’

‘I am a plain man. I speak in plain words.’

Hew said, ‘Plainly. Then let me tell you plainly once again, I have no interest in your wreck; now I will take my leave, and you will let it rest. There is a man of law, will serve you at the marketplace. He charges by the hour.’

‘Ah, do not take offence, for we are not as sleekit in our words as you. We cannot all be orators,’ the baxter smiled unpleasantly.

‘Indeed,’ retorted Hew. ‘And yet we can be civil.’

‘Aye, and that’s the point,’ James Edie interjected. ‘Are you not professor of the civil laws?’

‘That is the nomination,’ Hew agreed.

‘Then you can give us counsel, on a civil matter.’

‘As willingly, I will, when you ask a civil question.’

‘It is a question,’ said James Edie, ‘of the common good, and concerns the windmill. Will you not sit, sir, and consider it? It is a point of law.’

James Edie struck Hew as a decent man, although the same could not be said of Patrick Honeyman. By some secret notice, which had passed between the two, the deacon settled down and held his tongue.

‘Aye, then, what’s the matter?’ Hew accepted with a sigh. He saw no option but to stay and hear the baxters out. James Edie answered gratefully, ‘The matter here is this. As you must be aware, a windmill has been washed up in a broken ship. We four are come together here to help in her recovery.’

‘Which aid you offer,’ Hew suggested dryly, ‘from the comfort of the inn.’

‘We are convened, ye ken, in a consultative capacity,’ corrected Patrick Honeyman, ‘and call our privy council to oversee the rest. The mechanics of the task is as well left to the millers, for they have ingenuity, as well as the brute strength.’

‘The work is skilled and delicate,’ James Edie said, more tactfully, ‘and wants a careful hand. The mill itself is of great interest to the baxters, and if we could acquire it, would greatly serve the town. There are five watermills at present, grinding all the corn, to which the town is thirlit and bound to for their bread. The mill lade runs the course of the Kinness Burn, westwards from the shore to the Law Mill on the fringes of the town. The rents from the mills are split between the college and the ancient priory; though some are falling now to private hands. It has oftentimes been motioned, in our inner council, that if one or more of them were under our control, it would better serve the interests of the town.’

‘The interests of the town, or of the baxters?’ Hew inquired shrewdly.

‘Since I cannot think those interests are in conflict, they may coincide,’ admitted James.

‘As you yourself are not impartial in this matter. I’m told that you own land, on the Kenly Water, where there is a mill. In which case, ye will ken that your tenants must be bound to it, while you draw profit from the rents.’

Hew sensed he had been well dissected, in his time with Maude. Doubtless he was written, with the details of the mill, black and double scored, in the baxters’ secret book. He had small impact, and less interest, in the land at Kenly Green, and left it to his factor to collect the rents.

He was a landlord, nonetheless, in the eyes of Christie Boyd, who set aside his pen in a gesture of disgust. ‘Then his advice may not be worth a fart, for ye cannot expect him to uphold the common good. Most likely, he will want the windmill for himsel’,’ he commented.

‘That does not follow,’ answered Hew. ‘Yet you are free to judge it, as I hear your case. Is it that you want to have the mill?’

‘That is our intent, sir,’ James Edie said succinctly. ‘A mill in common ownership, and managed by the baxters, could only serve to benefit the town.’

Hew had no quarrel with the common ownership. Yet he suspected that the baxters’ plan would drive their prices up, ensuring the monopoly.

‘We have these past few years,’ James Edie said, ‘been subject to long winters, of implacable severity, and when the mill lade freezes, all five mills are stopped. And likewise in the summertime, the burn is prone to drought, and oftentimes, for half the year, the waterwheels lie still. What the town lacks – what it has lacked for too long – is a windmill. For windmills are not common in these parts, and are hard to come by. The winds on our coasts are far too wild and forceful to make them worth investing in for common use. We lack the will to build them, and we lack the skills. A windmill in a storm, such as we saw yesterday, is of little use. And yet . . . and yet, as a supplement, through cold, still, winter months, it would profit greatly if one could be acquired. And so, when she appeared . . .’

‘You might call it providential,’ Hew suggested.

‘Aye,’ agreed the baxter. ‘Like a gift from God.’

‘The problem though,’ Hew pointed out, ‘is that she is not yours.’

‘That is the rub,’ James Edie said, ‘for if we knew who owned her, we might buy her squarely, for the common good.’

‘Or else,’ said Patrick Honeyman, who lacked his colleague’s subtlety, ‘we might have control of her, in some other way.’

James Edie glanced at him, a quick and warning look. ‘We do not flout the law, but seek to understand it,’ he insisted. ‘The windmill’s place of origin remains a mystery. The ship is called the Dolfin – that is the porpoise, or the delfin fish, in Dutch, and not, as we suppose, the king of France. And yet she has not come here from our staple at Campvere. She was not expected, and no one in the town here kens aught about her fraught. Then since she is a wreck, we hoped that you might tell to us the process of the law. For some say that the town has title to the wreck, and others, that the whole is forfeit to the Crown. Pray, sir, which is true?’

‘In a sense,’ Hew considered, ‘neither and both. The shipwrack law is clear enough. In principal, the admiral decides, for shipwrack must be brought before his court. One part of the profit falls to the admiral, another to the Crown, and the third to any heritor who comes to claim his share.’

‘Then nothing to the town? But surely, when the town has gone to trouble and expense . . .’ Honeyman objected.

Hew shook his head. ‘I come to that. For often does the practice differ from the principle, and commonly the admiral will recompense the town. He is, in truth, quite likely to allow the town the windmill, since the cost of its recovery might well exceed its worth. However,’ he went on, ‘there is one provision. The law of shipwrack is reciprocal. Strangers wrecked upon our shores are treated here as they treat us, if we are lost to them. So if it comes from such a place, as returns our wrecks to us, then the cargo still belongs to the place from where it comes. If she is a Flemish ship, then they will have a claim on her. They have a year and a day in which to seek her out. If no one comes to claim her, then she will be shipwrack, and forfeit, as before.’

‘A year and a day?’ repeated Honeyman, incredulous. ‘It is a traveller’s tale!’