Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

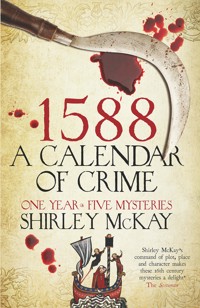

Yule is the fifth instalment of 1588: A Calendar of Crime, a collection of short stories published in step with the sixteenth century calendar. Despite prohibitions on celebrating Yule, the old traditions still persist among the tenant farmers on Hew's estate at Kenly Green. Hew defends a tenant against both Kirk and Crown when a violent accident befalls an unwelcome guest who has turned up uninvited to the feast.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 82

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Other titles in the Hew Cullan Mystery seriesHue & Cry Fate & Fortune Time & Tide Friend & Foe Queen & Country

Other titles in the Calendar of Crime seriesCandlemas Whitsunday Lammas Martinmas Yule

The complete collection of short stories:1588: A Calendar of Crime A Novel in Five Books

This eBook edition published in Great Britain in 2016 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd West Newington House 10 Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.polygonbooks.co.uk

eISBN: 9780857909169

Copyright © Shirley McKay, 2016

The right of Shirley McKay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Yule

It is easy to cry Yule at another man’s cost proverb

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Glossary

Also by Series

1.

The old miller’s son, John Kintor, at fifteen years of age, was learning to take care of Hew Cullan’s land. He was followed in his work on a clear day in December by a boy of six, who helped with the grafting of the cherry and the pear trees, so there would be fruit, and blossom in the spring.

The child, Matthew Locke, took note of all he heard. ‘There are grapes in the house. How is it that we have them in the winter time?’ he asked.

‘You maun ask your mammie,’ John Kintor said, ‘for that kind of alchemy. I dinna ken.’

‘Alchemy is making base things into gold,’ Matthew said.

‘Alchemy is cookery. How are the grapes? Are they good to eat?’

‘They are for the feast. I have not tried them yet. My daddie says that they are hot and moist, and an abomination at this time of year.’

John Kintor said, ‘He will drink them, no doubt.’

Matthew did not understand. ‘He says they puff the spleen and make it sick.’

John Kintor laughed at that. ‘Best not eat too many, then. Are you not wanted at your books the day?’

‘My master Gavan Baird says it is a ferie day, on account of Yule. But not to tell the Kirk,’ Matthew said.

John Kintor nodded. He was learning also, at the grammar school. But he did not have to go there every day. ‘Then you can help me with a special task. For it, we will want a length of strong rope. Run to the stable; they will gie you some.’

‘What task is that? Is it Yule work?’

‘It might be,’ John said.

There was Yule work all around. Gavan Baird had taught Matthew and his sister Martha three separate songs for the nativity. They were Gude and Godlie ballads, so the minister at kirk could hardly disapprove of them, though Gavan said he would. The children were to sing at the dinner in the hall, while their aunt Frances would play on her lute.

Martha could not mind many of the words. She sang the balulalow that Minnie used to sing to her to make her go to sleep. In between it, she pulled faces, like the ones the mummers pulled at the Lammas fair. ‘That will bring tears to your mither’s eyes. Your daddie’s too, I doubt,’ Gavan Baird had said.

‘Because it is so bad?’

‘Because you sing so sweetly.’

The thought of his parents weeping frightened him a little. ‘I do not want to mak my daddie greet.’

‘The tears will be joyful ones,’ Gavan Baird had said.

‘Did you ken a man can greet from happiness?’ Matthew asked John Kintor.

John said, ‘Are you not gone yet? Run, fetch that rope.’

Matthew went back through the house. He was fond of the stables, where as an infant he had learned to ride, but he never went without an apple for the horse, and another for the boy who had to clean him out. Dun Scottis was an old and filthy-tempered nag, and since he shared his hay with others more refined, there was a danger that he might be overlooked. That was in a verse Gavan Baird had read to him, all about a horse neglected at the Yule. It had made him sad.

The apples were kept in the laich house below, where the dry air smelt leathery sweet. Matthew liked to go there, to take his time to choose a pippin from the racks. But today, a basketful had been brought up to the hall, and the pippins had been polished to a blush. The apples had been piled up in a bowl, sitting on a board. The board had been covered with a dark green cloth. It also held a bowl of apricots and nuts, and on a dish beside them, in a kind of cluster, were the pale green grapes. They had a whitish bloom on them. Matthew reached to touch.

‘Don’t,’ said his mother behind him.

His mother’s arms were filled with holly boughs. She had made a wreath to hang upon the door. The holly and the rowan trees kept away bad spirits from the house. Now she tucked a sprig into the apple dish.

‘If I eat a grape, will I turn to gold?’

His mother laughed at that. ‘You are gold already, in your heart. But I do not want you to eat them now. They are for tomorrow, after kirk.’

‘It is fine an bonny in the house. But cauld,’ Matthew said.

The hall had been swept out, down to the bare bars of the great iron grate, with its bed of ash, naked of its flame. It was cold outside; the bright winter sunshine born of the frost did not warm the ground. John Kintor blew on his hands, and his frozen breath hung in the air.

‘It is warm in the kitchen,’ Minnie said.

He followed her inside it, and found a blaze of heat. A great haunch of beef roasted on the spit, while several pots and kettles bubbled on the fire. In a cooler place, his aunt and Bella Frew were making coloured tarts, of saffron, plum and spinach, and of almond cream. The tarts would be frosted with a sugar crust, which the flame would fix to make it look like ice. The ice would thaw to syrup, tasting like a rose, sweet upon the tongue. It was like winter and summer in one.

Martha was here too, helping to paint the marchpanes and the gingerbread, quilting them with nuts.

The tarts would be fired in the oven in the bakehouse. Minnie had an oven made of tiles, built into the thickness of the kitchen wall. But the oven here was huge, and had a man to fuel it. The tenants of the farms brought their cakes and loaves, saving them a walk and a penny for the baxter. What the bakers did not know could not hurt them, Frances said. For six or seven days, there had been a crowd of people in the park, coming with their cold plates and going back with hot. If they had no spice or currants for their pies, Frances gave them some. And the air round about smelt of cinnamon and cloves.

Matthew and Martha had been brought here by their mother, to help prepare the Yule. Their father would join them on the morrow for the feast, which was Yule itself, or what their aunt Frances still called Christmas day.

Frances had made minchit pies. They were filled with fruits, with spice and strips of flesh, and the scent that came from them was deep and rich and savoury. She told him of a pie that she had seen in London once, in a shop belonging to a pastry cook. That pie had been shaped like the castle at Windsor. Each of its turrets was a coffin crust, and each one was filled with a different kind of meat.

Aunt Frances said in London there were pies of birds and frogs. The frogs and birds were live. And when the pie was cut, they would all fly out. The trick was that the coffin had been filled with bran, and after it was cooked, a hole was made in it; the bran was all poured out, and the animals put in. That would be a dreadful disappointment, Matthew thought. For inside the crust would be nothing to eat.

Sometimes, Frances said, they put people under it, at the English court. A jester or a dwarf. Maybe a small child. Matthew did not see why that should please the queen. It would not please a man. His father’s face would fall, if Minnie baked a pie, and when it was cut open there was Martha in it.

His mother and his aunt, and Bella Frew, made cakes and biscuits for the feast of the Epiphany. The twelfth cake was vast, to feed the whole estate. Into it went pounds of raisins of the sun. Minnie made a smaller one, to share among the bairns. That one was bound up in a dough. When it was cooked, and the pastry cut through, the plums would be plump and heavy with spice, the cake sweet and moist, Minnie said. There was a secret inside.