5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

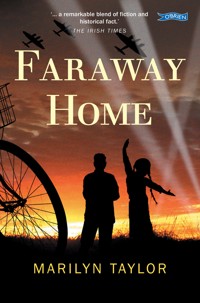

A web of secrets can risk lives … When Hetty's family move to Martin Street near Portobello bridge in Dublin, they're not sure of their welcome. And next door, Ben's family are not sure about their new Jewish neighbours: it's The Emergency and they are suspicious of strangers. But for Ben, the chance to earn a few pence is too great and secretly he does odd jobs for them. And there's a bigger secret: Renata, a World War Two refugee, is on the run in the city. Hetty is determined to rescue her. The web of secrets begins to unravel and there are lives at risk. Can Hetty and Ben overcome their differences and save Renata, or are they just meddling in things they know too little about?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

MARILYN TAYLOR

17 Martin Street

DEDICATION

For Hannah, Naomi, Dana, Samuel, Ariella, Matan and Elinoa, and their parents, to remind them – some time in the future – of their Irish roots

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All the people and institutions below gave me valued help with many aspects of this book.

I am especially grateful to my husband, Mervyn Taylor, without whose patient encouragement and support, and also factual knowledge and memories of his Dublin childhood, this book would probably not have been completed.

I would like to thank all at The O’Brien Press, and in particular my editor, Íde ní Laoghaire, whose tireless and enthusiastic help with the book over a long period, coupled with her kindness and consideration, are deeply appreciated.

My thanks to Renee Brompton, the Misses Cunningham (Greenville Terrace), David Elliott, Anne Kinsella, Donal McCay, Jacqueline and Willie Stein, Anita Weir, Marlene Wynn, Aubrey Yodaiken.

I also thank the Holocaust Educational Trust of Ireland (www.holocausteducationaltrustireland.org), the Irish Jewish Museum, Dublin City Libraries and South Dublin Libraries, especially Dolphin’s Barn, Pearse Street, Rathmines and Ballyroan. I would like to thank librarian Hazel Foster and the staff of Terenure Library, Dublin, for their assistance and co-operation with my numerous research requests both for this book and over many years.

I should like to thank Colman Pearce for permission to include ‘Growing up in Little Jerusalem’, which originally appeared in Jewish Dublin, Portraits of Life by the Liffey, by Asher Benson.

If I am not for myself, who will be for me?

If I am for myself alone, what am I?

And if not now, when?

The Jewish Talmud

No man is an island,

Entire of itself.

Each is a piece of the continent

A part of the main

And therefore send not to know

For whom the bell tolls,

It tolls for thee.

John Donne, ‘Meditation’

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Epigraph

Prologue: Extracts from Renata’s Diary 1938-1939

1 The Rescue

2 New Neighbours

3 17 Martin Street

4 The Broken Window

5 The Shabbos Goy

6 The Sanatorium

7 The Festival of Lights

8 Christmas

9 News of the Refugee

10 The Spy

11 The Dalkey Adventure

12 The Bombing

13 Money Troubles

14 Echoes of the Past

15 The Barmitzvah

16 The Football Match

17 My Mother Wore a Yellow Dress

18 Heart to Heart

19 For Whom the Bell Tolls

20 The Protest

21 The Visitor

22 Shelter

23 If Not Now, When?

24 Caught

25 Following Orders?

26 The Reunion

Epilogue: Extracts from Renata’s Diary 1941

Historical Note

Bibliography

About the Author

About Faraway Home, also by Marilyn Taylor

Copyright

Prologue

Extracts from Renata’s Diary 1938-39

translated from the German

Berlin, Germany: December 1938

Early on these grey winter mornings I get up as soon as I wake, listening to a bird singing in the leafless tree in the garden. Then I creep down to the kitchen and sit beside the warm stove to write my diary. It helps me to try and make sense of all that’s happening here in my home city where we’ve always lived.

My older brother, Walter, will be eighteen soon, but we won’t be able to celebrate his birthday like we used to as things are too hard now. Mutti says Walter’s ‘a bit of a dreamer’. He always has a pencil in his pocket and draws our portraits – and they’re really good. He gets my corn-coloured hair and green eyes just right. He wants to go to art school, but under the Nazis, Jews like us can’t attend schools and colleges with everyone else like we used to, only Jewish schools.

My sister Ella is pretty and she loves dancing, but she’s a bit spoilt because she’s the youngest. She wants to go everywhere with me, which can be a nuisance. Though I’m fifteen, my parents still treat me like a child. They don’t realise how quickly you grow up if you’re a Jewish girl living in Nazi Germany.

These are not good times. Rumours are spreading of bad things happening to Jews and others, round-ups and prison camps – no one wants to believe them.

My best friend Dina and I often talk about boys and clothes and what we’re going to do when we grow up. I want to be a doctor like Papa and she wants to marry and have six children, and be a famous actress too! But I’m afraid we’re living in a dream world while the real world around us is growing darker and more threatening.

Papa explained that the Nazis, led by Adolf Hitler, are powerful and ruthless. They’re using Jews as scapegoats for Germany’s problems, taking away all we have.

Already we must hand in valuables. My aunt’s flat was ransacked by the Nazi secret police, the Gestapo, and, because they found my great-grandmother’s box of tiny, blackened silver coffee spoons, they took my aunt and uncle away – no one knows where.

My parents queue for hours every day with hundreds of others trying to get visas to leave. You need to have a job in another country, and that’s very hard to get. Papa is from Poland, so we may go to Warsaw where we used to spend holidays with my grandparents. But yesterday he came home with a flash of hope in his eyes. He’d heard from a friend, Dr Lowy, about a small factory run by his Austrian cousin, Emil Hirsch, in a country called Ireland.

It’s very far away, but Dr Lowy is trying to get jobs there for himself and Papa, though neither ever worked in a factory. Maybe we can all escape from Berlin, the city where we were happy – till the Nazis came, and the horror began.

Berlin, January 1939

Today there are deep snowdrifts. In the old days we used to go sledding and tobogganing, but now we’re not allowed.

Things are getting worse, and Mutti has grown thin. Today Walter came home badly bruised. Seeing the yellow star that Jews have to wear on his jacket, Nazi Stormtroopers kicked and beat him when he refused to jump into the gutter to get out of their way. No one came to his aid. Battered and angry, he went straight to the Jewish Community Office to ask about ships to Palestine, the ancient country where Jews, young and old, are travelling to work the desert land.

Papa said Walter wasn’t cut out to be a farmer, and when I reminded him about his dream of being an artist, he said he could work by day and study art at night. ‘I refuse to be treated as an untermensch – I’m not sub-human,’ he saidheatedly, unlike his usual gentle manner. ‘You should all come. Germany is a hell for us now.’

But Papa said he was expecting a visa for Ireland, and he would send for us from there. ‘The British are in charge in Palestine and Jews can’t get in there now,’ he warned Walter. ‘You could end up in a detention camp–’

‘Couldn’t be worse than the prison camps here,’ Walter broke in.

Mutti wept, but a week later, with borrowed fare money and with our prayers and kisses, Walter departed, leaving us all desolate, like a tree with a branch cut off.

Berlin, March 1939

I miss Walter, my big brother who taught me to ride a bike and to skate, and always protected me. Ella keeps asking where he is now, but we’ve heard nothing.

People are disappearing – whole families – and we don’t know if they’ve escaped from the Nazis or been sent to prison camps. Dina went without saying goodbye; her house is shuttered up and there are new people, Nazis, living there. Mutti heard Dina had escaped to Britain on a Kindertransport with other Jewish children. Our names are on the list, but thousands are trying to get out.

Then one day Papa came home with Dr Lowy, waving precious visas for them to work in Ireland.

As they drank tea, I asked, ‘Where is Ireland?’

‘It’s near Britain – a small, beautiful island,’ said Dr Lowy. ‘It’s lush and green because it rains a lot.’

‘And it’s not ruled by Nazis!’ Papa picked up Ella and whirled her around.

‘Still, they don’t welcome refugees,’ put in Dr Lowy. ‘They allowed in a few people, including Emil, who’s from Vienna, to set up factories employing local people.’ He sighed. ‘But hardly anyone gets in now, even if they’re desperate.’

‘Can we go tomorrow?’ asked Ella.

But the visas were only for Papa and Dr Lowy.

‘I’ll find a way to get you all out of the clutches of the Nazis,’ Papa told us, ‘to safety in Ireland.’

I just hope he does.

Berlin, April 1939

It’s so lonely without Papa. It’s dangerous to go out and we miss our friends. Now I’m the eldest and I try to help Mutti and keep Ella cheerful. Although spring has come and the cherry trees are in bloom, our house feels empty and sad. As well as taking everything from us, the Nazis are breaking up our family. Who will be next to leave?

Papa has rented a room somewhere in Ireland. Mr Hirsch, the manager, helped him write to the Immigration Department in Dublin to get us entry papers. But though Papa has a job there, he still can’t get permission to bring us over.

Our shoes are in holes. Ella cheered up when we went shopping, though we can only afford second-hand shoes, and anyway most shops won’t sell to Jews. Ella complained that the wooden clogs we had to buy are very clumsy. ‘I can’t even skip in them.’ She showed us and she was right.

As we returned, our neighbour rushed out. ‘A black car full of SS men arrived after you left,’ she told us fearfully. We all knew these were the Nazi officers in leather coats and polished boots. They had rapped on our door. ‘They’ll come back,’ she whispered. ‘You must all leave.’

We were terrified, but Mama told us to pack warm clothes quickly. Tonight we will take the train for Warsaw where Papa’s family will take us in.

On the train – no time to write more –

Warsaw, Poland, August 1939

We’re in a small house with my grandparents, uncle, two aunts and our cousins. Warsaw is a fine city, though we’ve heard there are people here too who hate Jews.

But Christian friends of Papa, Casimir and Berta Pavlak, have helped us with money and food. They’re angry at what’s happening in Germany to Jews, and also to others, even Christians, and they pray the Nazis don’t invade Poland. So do we.

Until Mutti can get a sewing machine she helps my aunts do other people’s washing by hand on a wooden board. It’s very hard work, and sweaty too – I hope I don’t have to do it. The whole house smells of soapsuds and damp clothes.

We’re all homesick for Berlin as it was before the Nazis. I miss Dina and my other friends and the fun we all used to have. Today Papa sent us some money, and writes that he has a plan to get a temporary Irish visa for me. But only for me.

When I heard this I burst into tears. How can I travel alone to a faraway land, without Mutti and Ella? When would I see them again?

Uncle said, ‘It’s hard to be uprooted again, Renata, but you must go.’ He explained that if the Nazis invaded Poland they would force all Jews into a kind of ghetto, where thousands would live crowded together in hunger, misery and disease. We shivered.

‘If Papa gets you a visa,’ Uncle added, ‘maybe he’ll get your mother and Ella out later.’

‘And then,’ Mutti said, trying to smile, ‘we’ll be together in Ireland.’ No one said: Except Walter.

So now I know – the next one in my family to leave will be me!

1

The Rescue

Dublin, Ireland, Winter 1940

‘Ben, did’ya hear? The canal’s frozen over.’

Ben Byrne looked up from his bowl of porridge. Beside him his brother, Sean, was wolfing down slices of fried bread as fast as Granny could tip them, sizzling, out of the heavy frying pan and on to his plate.

‘It’s great gas,’ Sean went on. ‘Everyone’s sliding on the ice, even kicking a football around on it.’ Between mouthfuls he said to Ben, ‘You could go down after school and have a game with Smiler and the others.’

Sean, three years Ben’s senior, strong and thickset with a loud voice, spoke in the condescending tone he’d acquired since he and some of his pals had become official messengers helping with Air Raid Protection in the Emergency. They whizzed around Dublin on their bikes, sporting ARP armbands and gas masks slung in a box over the handlebars, collecting buckets and hoses for fire practice. There’d been no attacks or fires so far, but that didn’t seem to weaken their enthusiasm or sense of importance.

‘Don’t you be playing games on the ice, Ben,’ Granny put in quickly. ‘It’s treacherous. We’ve enough trouble in the family as it is.’ She turned to Sean. ‘You should know better, a big lad of fifteen, working and all–’

But Sean, muttering ‘late for work’, grabbed his packet of jam sandwiches, hauled his bike outside and dashed off to his new delivery job at the White Heather laundry.

***

Early that morning fresh snow had fallen and when Ben stepped into the white street he was aware of a strange, muffled hush.

But later, coming home from school, his hands so stiff with cold that he could barely grip the strap around his school books, the snow in Synge Street had been stirred into a grey, lumpy mush by people and horses and the few cars that were still around these days.

Ben peeled off from the other boys, who were calling to the sweet shop on the corner of St Kevin’s Road to get sticks of liquorice or maybe even a hard-to-find KitKat bar. But though Sean was working now, Ben knew his Mam’s sickness was costing the family, and he didn’t even have a penny, let alone twopence for a KitKat.

The canal lay at the end of Martin Street in Portobello, where the Byrne family – Mam and Dad, Granny, Sean and Ben – had moved a year earlier from a teeming tenement in New Street where the boys had grown up.

Ben still hadn’t got used to the green peace of the canal bank. The grass, in summer soft and lush, was now stiff and frosty, scraping Ben’s bare knees as he squatted down. Instead of the procession of low barges carrying turf sliding slowly past, there was now a sheet of greyish-white ice, shining in the distance like a mass of tiny diamonds. There was no sign of a football game, but further down children were sliding, falling and shrieking on their new icy playground.

Idly, Ben was wondering where all the ducks went when their watery home froze, when there was a sudden movement beside him. A man appeared, flung a bulging sack into the canal, and made off.

The ice cracked and the sack sank into the murky water. Ben jumped to his feet as it surfaced again. It moved strangely, with high-pitched squeaks issuing from it.

Seconds later a girl came from nowhere, running like a deer towards Ben, her eyes on the sack. It was now almost submerged in the dark circle that had opened up in the ice.

Reaching the edge of the bank the girl squatted down and began to unlace her boots. ‘Quick,’ she said urgently to Ben, ‘there’s something alive in that sack.’

‘It isn’t safe,’ he told her, uncertain what to do. ‘We should get help.’

‘There’s no time,’ she snapped.

Granny’s words that morning flashed across Ben’s mind. Surely it wasn’t worth taking a risk on the ice? But he turned and saw the girl’s face clearly – a mop of dark curly hair and angry, blazing eyes commanding him to help. He picked up a fallen branch from the bank.

‘I’ll slide over and try to fish it out,’ he said, with a bravado he didn’t really feel. ‘You hang on to me in case the ice gives way.’ He took off his glasses and put them in his pocket.

Gingerly, he lay face down on the ice, which was as rigid as iron yet fragile as eggshells beneath him. The cold burned his skin as he inched towards the sack, now almost completely underwater and hardly moving. Cautiously sliding closer, he reached out with the stick, trying unsuccessfully to lever the bundle up out of the jagged hole.

Fear stopped him short. Even if he reached the sack, how was he going to get it – and himself – back to the bank?

There was a touch on his leg. Turning his head, his face stinging from ice-burn, he realised the girl had tied something to his ankle.

‘It’s all right,’ she called. ‘I’ll pull you back. Be careful not to crack the ice.’

Encouraged, he slid a little further along. Using the stick and all his strength, he managed to raise the sodden sack out of the water.

Exhausted, he lay spread-eagled, his numb fingers clutching a corner of the sack, now ominously still and silent.

There were a few tugs on his ankle as the girl attempted unsuccessfully to pull him in. Raising his head he looked back. Without his glasses everything was a blur. He was a prisoner, almost unable to move, his strength waning.

After what seemed like an age he felt another, stronger tug, and found himself slowly and painfully gliding back to the bank. Then, still grasping the sack, he was back on the grass. With an effort he rolled over and saw the heavy winter sky leaning down over him.

Shakily he sat up and put on his glasses, his face and body chilled yet burning, and his legs sore and scratched. He and the passer-by who’d helped pull him in watched as the girl opened the sack and scooped out three puppies. They all inspected the tiny, pathetic creatures – two chocolate brown splotched with white, wriggling, the third stiff and silent.

‘Looks like he’s a goner,’ said the man who had helped.

Gazing down at the little creatures with anger and pity, the girl muttered, ‘How could anyone do such a wicked thing?’

‘They probably couldn’t afford to feed them. Times are hard,’ said the man. ‘Stay off that ice, now.’ And he went away.

‘It’s so cruel.’ She clutched the puppies to her, and to his embarrassment Ben saw a tear trickle down her cheek.

‘At least we saved two,’ he muttered awkwardly.

‘I must get them to my uncle’s to feed them,’ she said. ‘He lives near here.’ And without a word of thanks or farewell, she hastened off, the puppies in her arms.

Ben was left sore, uncomfortable and puzzled. Unusually, he had done something that required courage – mostly thanks to that girl. And now she’d just gone.

Back at home, he didn’t dare tell his dad about the incident. He told Granny he’d slipped, wincing as she dabbed his sore legs with lint soaked in brown iodine.

But in the weeks ahead he often replayed the scene in his mind, wondering if he’d ever find out the fate of the puppies, or who that furious, headstrong girl was.

2

New Neighbours

A few weeks later Ben, seated on the edge of his iron bed in the chilly upstairs bedroom of Number 19 Martin Street, was watching out for the glimmer man.

Further down the street between the rows of terraced houses, packed tight as teeth, a football game was in progress. The shouts of his brother Sean and Ben’s friend Eamon – known as Smiler on account of his cheerful nature – echoed enticingly up from the street. But he was stuck here for another half-hour, while downstairs in the kitchen Granny hurried to make tea before Dad left for the early-evening shift with the Local Defence Force, the LDF.

Ben could lean out and roar through the window to Smiler, or maybe Sean, to come and take a turn on the watch. But in the next room their mother lay sick, and if he woke her, he’d be murdered.

Ben had never actually seen the glimmer man – a uniformed inspector from the Gas Company who cycled around the streets of Dublin on an orange bicycle. If he discovered anyone evading gas rationing by lighting the tiny whiff left in the pipes when the gas was officially turned off, then the Gas Company might fine them, or even cut off their gas altogether so they couldn’t cook anything except over a smoky fire. ‘And then,’ as Granny said, ‘how would we feed a family with two hungry boys?’

So it was Ben’s task to watch out and warn Granny and the neighbours. Ben pictured the official striding into the kitchen and putting his hand on the gas ring to check if it was warm – proof that Granny had been cooking on the ‘glimmer’. He imagined Granny in tears, his dad raging that he’d have no hot tea before he left, his mam up in bed listening anxiously to the commotion below. He sighed – better forget about football and concentrate on his lookout job.

He was almost nodding off with boredom when from the far end of the street he heard a distant grinding rumble, too noisy to be the glimmer man’s bike. Slowly, an odd procession came into view: a woman in a drab woollen dress and headscarf, carrying a bundle of blankets. Behind her, hunched with the effort of pushing a laden handcart, was a bearded man in a long overcoat and soft felt hat, and two girls, the younger about Ben’s age.

As the cart ground to a halt below, the man straightened up, mopping his forehead with a handkerchief. Approaching the house next door to Ben’s, empty since old Granny Murphy had gone to live with her daughter, he peered at the number, took out a key and unlocked the front door.

New neighbours at last! Pity there was no sign of a boy his own age who might become a friend, joining in the football or playing marbles or conkers or swapping cigarette cards. When Ben had first come to live in Martin Street only a year ago, some local boys had called out mockingly, ‘Specky Four-eyes!’ on account of his glasses. Smiler, a bit younger than Ben, was his only real friend here, and he still missed the pals he’d grown up with in New Street.

Below, the woman entered Number 17, cradling the bundle which Ben could now see was a baby wrapped in blankets. The others all seized parcels and boxes, and began to carry them inside.

Ben leant perilously out of the window to watch. Should he go down and offer to help? The older girl spotted him and said something to the younger one. Staggering under the weight of a heavy box, the younger girl followed her sister’s glance, squinting up into the wintry sun; then, frowning, she tossed her mass of curly hair and bent down.

Ben wiped his smeary glasses and had another look. There was something familiar about her. And then she opened the box and let out a frisky brown and white puppy, which darted in and out of everyone’s legs, yapping furiously.

Ben nearly fell out of the window. It was her, that girl! He recognised now the unruly hair and the thick eyebrows drawn together in a frown. And the puppy must be one he himself had helped to rescue. What had happened to the other? And why was that girl so cross? Didn’t she recognise him? As questions buzzed in his mind the family below speedily humped in all the boxes and furniture and disappeared inside the house.

***

‘Ben, the gas is on!’ The welcome shout floated up from downstairs. ‘Come and get your tea.’

From Mam’s room, beside his and Sean’s, there was no sound. Trying to stop his boots from clattering on the bare wooden stairs, he ran down.

At the bottom he cannoned into Sean, dashing in from the street. ‘You missed a great game,’ he told Ben. Ben grunted. Trust Sean to add salt to the wound.

They sat at the table opposite their dad, hidden behind the Evening Mail, and began to eat the sausages and baked beans dished out by Granny.

‘That old damp turf,’ she grumbled as their eyes watered from the acrid smoke billowing out from the grate. ‘There’s barely any heat out of it. God be with the days when we had coal.’

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)