Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

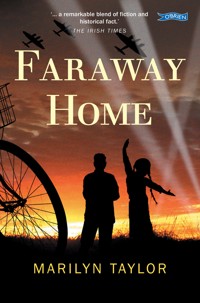

Karl and Rosa's family watch in horror as Hitler's troops parade down the streets of their home city -- Vienna. It has become very dangerous to be a Jew in Austria, and after their uncle is sent to Dachau, Karl and Rosa's parents decide to send the children out of the country on a Kindertransport, one of the many ships carrying refugee children away from Nazi danger. Isolated and homesick, Karl ends up in Millisle, a run-down farm in Ards in Northern Ireland, which has become a Jewish refugee centre, while Rosa is fostered by a local family. Hard work on the farm keeps Karl occupied, although he still waits desperately for any news from home. Then he makes friends with locals Peewee and Wee Billy, and also with the girls from neutral Dublin who come to help on the farm, especially Judy. But Northern Ireland is in the war too, with rationing and air-raid warnings, and, in April 1941 the bombs of the Belfast Blitz bring the reality of war right to their doorstep. And for Karl and Rosa and the other refugees there is the constant fear that they may never see their parents again. Based on a true story -- there was a refugee farm at Millisle and among its occupants was a young boy called Karl.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 228

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FARAWAY HOME

MARILYN TAYLOR

For Hannah, for later

Come away, O human child,

To the waters and the wild …

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.

W.B.Yeats

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

PART ONE Anschluss! Karl & Rosa: Vienna, 1938

1 Anschluss!

2 The Iron Ring

3 TakenAway

4 Swastika

5 Lisl

6 The Return

7 Kristallnacht

8 The Merry-go-round

9 Leaving

PART TWOA Strange Land: Karl & Rosa: Belfast, 1939

10 Ireland

11 Rosa’s Doll

12 Another Journey

13 The Farm

14 The War Comes

PART THREEThe Farm: Judy, Karl & Peewee: Dublin & Millisle, Summer 1940

15 The Bombshell

16 Over the Border

17 Enemy Aliens

18 Chickens

19 Rescue!

20 Homesickness

21 Dancing the Hora

22 The Letter

23 Remembering

24 Saving the Hay

25 The Convoy

26 Spies!

27 The Ulster Tea

28 Air-Raid Warning

29 Football Practice

30 War News

31 The Accident

32 The Match

33 Whereis Home?

34 Arrival and Departure

35 Afterwards

PART FOURLiebe Judy: Karl & Judy’s Letters: Dublin & Millisle, Sept 1940

36 Winter 1940

PART FIVEBlitz!: Karl, Judy & Peewee: Millisle, Easter 1941

37 Bad News

38 The Plan

39 Running Away

40 Blitz on Belfast

41 The Dublin Fire Brigades

42 One More Death

43 The Road to Millisle

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

About the Author

Copyright

PART ONE

Anschluss! Karl & Rosa: Vienna, 1938

1

Anschluss!

Karl Muller looked down from the window of his family’s apartment, high on the fifth floor, to a scene unlike anything he had witnessed in all his thirteen years.

‘Victory to the German Reich! … Sieg Heil! … Jews out!’

The raucous shouts floated up to the curtained window behind which, hidden from view, the Muller family crouched. Below in the Vienna streets, green army lorries thundered past, packed with steel-helmeted soldiers who sat stiff and motionless, clasping machine-guns. Uniformed motorcyclists zoomed by in formation, churning the sprinkling of late snow to a dirty slush. Huge blood-red flags with black swastikas, the Nazi symbol, swayed and rippled.

The cries redoubled. ‘One Reich, one people, one leader … Anschluss!’

In a sudden hush, broken by the peal of church bells, an open-topped car drove slowly down the centre of the road. In it, erect, right arm outstretched in the Nazi salute, stood the Nazi leader of Germany, Adolf Hitler.

Karl, with his parents and his little sister Rosa, watched silently as an animal roar erupted from the crowd. Could this really be the man who was taking over their city, their country? This ordinary little man, with a ridiculous moustache, turning to left and right like a mechanical doll?

Despite the heat from the tiled stove, Karl felt suddenly cold. Hugging his dog, Goldi, he gazed over the red-tiled rooftops and slender church spires, to the Prater funfair. He had visited the fair countless times, whirling round on the giant Ferris wheel with its view over Vienna, stuffing himself and Rosa with ice cream while the grown-ups listened to the band. At home and at school, his life had been ordinary, uneventful, sometimes boring.

But now the unthinkable had happened. The Nazis had taken over Austria. They called the take-over the Anschluss. What was it going to mean, Karl wondered – to him, and to everyone around him?

Rosa tugged at her father’s jacket. ‘Papa, what are they shouting?’ she asked. ‘I want to join the parade. I’m wearing my dirndl.’ She twirled to show off her coloured skirt and embroidered blouse, the Austrian national dress she liked to wear.

Her father patted her head. ‘No, darling,’ he answered slowly. ‘We can’t join in. They don’t want us.’

As Rosa, disappointed, turned to her mother, a dazzling flash of light from below forced them all to step back from the window.

‘What’s that?’ asked Rosa, her hands over her eyes.

‘They’re flashing mirrors up to blind us,’ said Papa. ‘Maybe they don’t want us to see their beloved Hitler.’

‘Surely not,’ said Mama. ‘How could they know which are our windows?’

‘The ones without Nazi flags, I suppose,’ said Papa. ‘You know Jews aren’t allowed to display the swastika. As if we’d want to!’

‘Those people screaming down there can’t be ordinary Austrians,’ said Mama. ‘Our friends and neighbours–’

‘No?’ Papa replied bitterly. ‘People seem to have forgotten decency, justice–’ He drew a handkerchief from his pocket and blew his nose. ‘Overnight, they have become supporters of Hitler and his bully-boys.’

‘But Papa, aren’t there people who are against the Nazis?’ asked Karl.

Papa shrugged hopelessly. ‘The Social Democrats? They’re probably hiding away in their homes, like us.’

Karl had never seen his father like this, bitter and sad. He longed for the reassuring tones Papa had always used when he was a little boy, with little problems and fears. But this – the Nazi parade, the swastikas, the hysterical screaming – was a problem that even Papa was powerless to deal with.

Karl felt as if somewhere, deep in some hidden place, a sleeping monster had stirred and was beginning to wake.

Karl and Rosa’s grandmother appeared from her bedroom, pulling a lacy shawl around her. ‘What’s happening out there? It’s so noisy …’ She tucked her long grey hair into a knot at her neck. ‘Why are you all hiding behind the curtains?’

‘It’s a parade,’ Rosa told her importantly. ‘But we can’t be in it, Oma.’

‘It’s Hitler’s victory parade, to mark the Anschluss,’ said Mama matter-of-factly. But Karl could hear a tremor in her voice. ‘It must be nearly over now.’

‘I don’t understand,’ said Oma. ‘Isn’t there going to be a vote about us joining with Nazi Germany?’ Her eyes, which her diminishing sight had turned a pale milky blue, were bewildered. ‘I thought a lot of people were going to vote against it – there were posters everywhere, and signs painted on the footpaths–’

‘That vote isn’t going to happen.’ Papa led her to the settee. ‘Our spineless government caved in to Hitler’s bullying and cancelled it. Now Germany has taken us over, and we’re under Nazi rule.’

Nazi rule. With a chill, Karl remembered his father reading aloud the news from Nazi Germany – Jews beaten and attacked, driven from their homes, sent to prison camps.

‘But this isn’t Nazi Germany,’ said Oma. ‘Our Austria is a country that cares for all its citizens, whatever their religion.’

‘Suppose the Nazis change things–’ said Karl anxiously.

A knock at the door made them jump. Papa rose. Mama hurried in from the kitchen. ‘Don’t answer,’ she hissed. ‘It might be the Nazis, come for us.’

They all stood frozen, waiting.

There was a second knock, still soft.

‘If it was them, they would bang on the door and shout,’ whispered Karl. ‘And look at Goldi.’ She was standing quietly, waving her bushy tail.

Papa opened the door a crack. ‘It’s all right,’ he said. ‘It’s only Rudi.’

Everyone brightened at the sight of Uncle Rudi, Papa’s younger brother, smart in his camel hair coat.

‘I had to come,’ said Rudi. Karl could see that his uncle, an actor usually full of jokes and chatter, was making an effort to sound solemn. ‘On such a day, the family should be together.’ Rudi embraced his elderly mother tenderly and greeted the family. As soon as Rosa ran to him, he became his old self, swinging her up in his arms. ‘And how’s my favourite niece?’

Giggling, she patted his luxuriant chestnut hair and curly moustache. ‘I’m your only niece, Uncle Rudi,’ she said as he set her down. ‘Did you see the parade?’

‘I heard it on the radio,’ he said. He turned to Papa. ‘They’re welcoming Hitler and the Nazis like saviours.’

‘You heard what they’re shouting about Jews?’ asked Papa.

Rudi shrugged. ‘It will pass,’ he said. ‘Our history is full of these troubles, and we’re still here.’

Mama, glancing around at the solemn faces, said briskly, ‘I think we should forget the Nazis and eat. Come, Oma.’

But, Karl thought, how could you forget the monster, nameless and terrifying, that was out there in the once safe and familiar streets of their city?

2

The Iron Ring

Rudi switched on the radio, which sat, squat and square, on the polished sideboard. ‘… children are strewing flowers along the route of his car. The people of Ostmark are full of love and admiration for our leader, Adolf Hitler, himself an Austrian …’

‘Ostmark?’ said Karl. ‘What’s that?’

‘It’s the new Nazi name for Austria,’ grunted Papa.

The voice on the radio spoke reverently, excitedly. ‘Germany and Ostmark, united, will go forward to a glorious future, destroying our enemies–’

Papa switched it off. ‘Mark my words, ours is the first country Nazi Germany has swallowed up, but it won’t be the last. And when Hitler has all Europe in his power, he’ll set about destroying those he hates – Jews, Gypsies, Socialists, and everyone who defies him.’

‘You’re such a pessimist,’ said Uncle Rudi, putting his arm affectionately around Papa. ‘I tell you, the Nazis won’t last.’ He ran his hand through his untidy hair with an actor’s casual gesture. ‘At the theatre, everyone thinks that man’s a joke.’

He leapt to his feet; laying one finger across his upper lip, he extended the other arm stiffly and strutted up and down the small living-room in an imitation of Hitler. Goldi, thinking this was a new game, trotted after him, barking.

Karl laughed, but Papa remained serious. ‘You make a joke out of everything, Rudi,’ he said. ‘But the Nazis are no joke. What happened in Germany could also happen here.’ He stopped as Rosa appeared from the kitchen, carrying a platter of warm rye bread.

Uncle Rudi said, a little too heartily, ‘Something smells wonderful.’

As the family sat round the heavy oak dining-table, it seemed to Karl that Papa’s and Uncle Rudi’s words still hung in the air like a chilling echo, not quite concealed by the family laughter and argument – Papa praising Mama’s feather-light potato dumplings, Uncle Rudi waving his arms about as he talked, and Goldi, her tail thumping hopefully, waiting beside Rosa’s seat for bits of salami.

They all tried to ignore the occasional shouts and snatches of Nazi marching-songs that could still be heard from outside. Instead, Uncle Rudi told them about his part in a new comedy at the Burgtheatre; and Oma repeated the familiar story of how, in the Great War, the Austrian army had awarded her husband, Karl’s grandfather, the Iron Cross for his courage in rescuing a wounded man from the mud of the trenches. ‘I was proud of your dear Opa, but so worried about him. He came back a changed man. They called it shell-shock.’ She paused, remembering. ‘It was a terrible, needless war.’

‘Tell us the story of the ring, Oma,’ begged Rosa.

Oma put down her knife and fork. ‘Well, darling, during that war the government asked all women to give gold and jewellery to help our country’s war effort. You know we only had the small shoe shop which your Papa runs now, so I gave the most precious thing I had.’ She lifted her hand. ‘My gold wedding ring, that your Opa had worked and saved for.’

‘Didn’t you get it back, Oma?’ asked Rosa, knowing the answer.

‘No, darling,’ said Oma. ‘They gave us rings of iron in exchange.’ She held out her claw-like hand, the iron ring loose on her bent finger.

As they ate and talked, Karl felt his earlier icy fear recede in the warmth and security of the family meal. After lunch, perhaps he would go round and have a game of football with his cousin Tommy, or visit Lisl, his closest friend. She and Karl had always told each other everything, and it had never mattered that she was Christian and he was Jewish.

Maybe Uncle Rudi was right, he told himself, the Nazis would disappear, the unnerving cheering and jeering would stop, and life would return to normal again.

They were still at the table when they heard violent banging. Goldi raced to the door, barking. Karl’s stomach lurched. This time there was no mistaking who it must be. Fear pervaded the room.

Papa rose and gestured to Karl, who, fighting down the terror that rose inside him, led Oma and Rosa into the small study beside the dining-room. His mother went to stand beside Papa and Uncle Rudi. Karl gripped Goldi tightly to him as she gave a low growl.

There was another volley of crashes against the door, and a voice shouted, ‘Open up, Jews!’

3

Taken Away

As Papa opened the door, a black-uniformed officer, wearing on his cap the skull badge of the dreaded Nazi SS, pushed past him and strode into the room. Behind him was a local Viennese policeman whom the Mullers had known for years – but now, Karl saw with a shock, wearing a swastika armband.

The officer glared round the room. In the moment of silence, a tiny stifled sob was heard from the study.

‘Get the Jewish scum out from there,’ the officer ordered the policeman. As Goldi growled, he turned to Karl. ‘Shut that animal up, or we’ll throw it out of the window.’

Karl rushed to shut Goldi in the kitchen, his body responding without conscious thought. The policeman pushed Rosa and Oma, holding each other, both crying softly, into the room. At the other side of the kitchen door, Goldi whined and scratched.

‘Shut up, all of you,’ shouted the officer. They gasped as he pulled out a gun. ‘We’ve come for Muller, Jew and Social Democrat supporter.’

Papa stepped forward, his face grey.

‘Where are you taking him?’ Mama’s voice shook.

‘For now, to do some street-cleaning,’ said the officer, grinning unpleasantly. ‘And maybe other things.’ He turned to Karl. ‘You, fetch toothbrushes. Nothing else.’ Did that mean Papa wouldn’t be back tonight? No one dared ask.

As Karl re-entered with the toothbrushes, the policeman grabbed Papa and dragged him to the door. Rosa let out a frightened wail.

The officer turned to Uncle Rudi. ‘You too!’ he barked.

Ignoring him, Rudi bent to comfort Rosa. Without a word, the officer swung round and struck him on the head with his gun. They all heard the sickening crack. Rosa screamed as Rudi fell to his knees, blood trickling down his cheek.

Papa bent to staunch the wound with his handkerchief. The SS officer motioned to them with his gun. ‘Get going!’

Rudi struggled to his feet, Papa’s blood-soaked handkerchief pressed to his face. From the kitchen, Goldi let out a mournful howl.

At the door, the SS man roared, ‘None of the rest you is to leave this apartment!’

For a moment they waited in fearful silence, which was broken only by Rosa’s whimpers. Karl could hear them stumbling down the stairs. He hurried to the window. Below, he could see Uncle Rudi, leaning on Papa, struggling along the street, followed by the two Nazis. He watched them until they vanished round the corner.

They tried to fill the endless hours of waiting with little jobs and strained conversation. Mama put out some food, but no one was hungry. Oma sat by the window, peering down at the darkening street. Rosa, refusing to go to bed, fell asleep on Mama’s lap.

And then, much later, Oma called from the window, ‘Quick, Karl! Here’s Papa!’

Through the crack in the curtains, a lone figure could be seen below.

Karl was halfway down the stairs when it struck him. Where was Uncle Rudi?

At first Papa could hardly speak. His clothes were torn and splashed with mud and grime, his hands bleeding, his eyes raw and inflamed behind the cracked lenses of his spectacles. He gripped Karl tightly and Karl could smell a sour whiff of sweat and something chemical and pungent.

‘Thank God you’re back safely,’ cried Mama, rushing to the kitchen to heat soup for him.

‘Where’s Rudi?’ asked Oma. ‘What happened?’

There was no reply. Karl’s heart began to bang uncomfortably.

Then Papa said slowly, ‘We had to scrape the anti-Nazi posters off the walls with our fingernails.’ He grimaced. ‘People were shouting and jeering. Ordinary Austrians like us, families with children.’ He blinked his sore eyes. ‘Then we were forced to kneel on the pavement and scrub off the slogans, with toothbrushes. For a joke, they said.’ Glancing down at his swollen hands, he went on, ‘They poured ammonia over us, to burn our skin. All the time the SS, the Hitler Youth, they were screaming at us, shouting filthy things–’

‘Were there no police there?’ whispered Mama.

‘Our own police stood by, even helped them. Then–’ His voice broke. Mama held him tight. Finally he continued, ‘One of them kicked an old woman who was on her knees beside us, scrubbing. I whispered to Rudi to keep quiet, that it would soon be over. But you know Rudi. He stood up and shouted, “Leave her alone! Is this what you Nazis stand for? Abusing people, kicking old women?” They beat him up–’ He swallowed. ‘And when I tried to intervene, they kicked me to the ground. Then they dragged him off.’

There was an appalled silence.

‘Where did they take him?’ Mama asked shakily.

Papa hesitated. ‘They said – Dachau.’

Karl paled, recalling the horror stories they had heard about Nazi prison camps.

Oma drew a long, shuddering breath.

‘They said it was for a few weeks, so that he would “learn manners”,’ Papa told her. He added, trying to sound confident, ‘I’m sure he’ll be back.’

Much later, in bed, thinking about all that had happened that day, Karl felt as if he had suddenly grown older – as if his childhood had flown away from him, leaving a new Karl, harder, angry, expecting the worst.

4

Swastika

On the tram to school on Monday, it soon became clear to Karl that his city – charming Vienna, with its tall, elegant buildings, its almond trees just coming into blossom – had been transformed by the Anschluss.

Gone were the red-and-white Austrian flags that had been everywhere in the weeks leading up to the expected vote. Instead, almost every building was decorated with black-and-red swastikas and bunting. Huge portraits of Hitler gazed down from hoardings. The old Café Splendide, where Oma used to bring Karl and Rosa for a special treat, had become overnight the CaféBerlin, flying a Nazi flag with a sign: ‘Jews not wanted here.’

On the tram, those not in Nazi uniforms had swastika pins or armbands. Youngsters were decked out in blue-and-white Hitler Youth uniforms. Small children carried Nazi flags. Even a little sausage-shaped dog was wearing a jacket with a swastika.

How could things change so quickly? Overnight, Karl had become an outsider in his own city. A cloud of loneliness enveloped him.

A voice said, ‘Karl!’ He looked up to see Lisl, her long dark hair gathered by a velvet ribbon, taking the seat beside him. But today, instead of their usual easy chat, there was an awkwardness between them.

After a moment Lisl asked, her usually clear voice low, ‘Was it a bad weekend?’

‘Not good.’

She hesitated. ‘I heard hundreds of people were arrested.’

‘Uncle Rudi, too.’ Karl tried to keep his voice steady. ‘And my father had to scrub the streets.’

‘I saw some of it,’ said Lisl quietly. ‘It was horrible.’

As the tram neared Karl’s school, she said, ‘Those Hitler Youth are everywhere, all of a sudden, with their fancy uniforms. My father wants me to join.’ Seeing Karl’s expression, she added firmly, ‘Don’t worry, I told him I wouldn’t. These Nazis aren’t going to stop us being friends just because you’re Jewish.’ As Karl rose to get off the tram, she gave him her cheeky grin.

In school, at first, everything appeared reassuringly unchanged. At morning assembly, Herr Klaar, the headmaster, addressed them, his voice low. ‘My dear students, these are bad times for the citizens of our country – and I mean all citizens, who should be protected by the State. We must pray for our beloved Austria–’

‘Ostmark, you mean, Herr Klaar,’ bellowed Herr Seiss, the maths teacher, jumping to his feet. ‘And surely we should honour our new leader?’ Thrusting out his arm, he roared, his eyes on his fellow teachers, ‘Heil Hitler!’

Several teachers and students followed suit, some enthusiastically, a few half-heartedly. No one looked at Karl, or at any of the other Jewish pupils.

On the platform, the headmaster faltered. Then he said, ‘I would rather say, “God bless you all”.’

Summer came, but it was different from any previous summer. To Karl it seemed as though everything was slipping out of its place, going wrong, like music jangling out of tune.

New laws were constantly being announced, laws restricting the lives of Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, handicapped people – all now to be known as ‘non-Aryans’. Karl’s parents, along with all other Jews, were notified that their children could only attend Jewish schools. Jews had to sit in the rear sections of trams; they couldn’t go into non-Jewish shops, restaurants, sports centres or swimming pools; they had to sell their apartments and businesses to Nazis for next to nothing.

‘It’s wholesale robbery,’ said Papa, his face creased into a worried frown. ‘I suppose they’ll soon take over the shop. With the anti-Jewish boycott, it’s hardly making anything, but it’s all we’ve got.’ They had already sold Mama’s jewellery and Papa’s watch, and the piano that had belonged to Oma and Opa, and they were living on fast-disappearing savings.

Papa had put advertisements in the English papers seeking work as a gardener, a labourer, a domestic – no job was too menial. But there was no response. Every day Papa and Mama set off on a weary round of offices and consulates, to try and get visas so that the family could leave. But virtually no country was interested in letting in penniless Jewish refugees. They returned wearily late in the evening, to eat the meal prepared for them by the children and Oma, who had grown feebler and more fearful since the Anschluss.

And all the time, people were disappearing. At Karl’s new school, every morning they checked to see who was missing. The lucky ones, with relatives or friends abroad who could guarantee them jobs, were leaving the country. The others had been arrested, or had gone into hiding.

Austria itself had become a prison camp for Jews. And as the net closed in, increasingly, their ‘Aryan’ friends abandoned them.

5

Lisl

On a Sunday in late summer, Karl set off on his bike to visit Lisl. Before the Anschluss, they had cycled together every weekend in the Vienna woods, under trees frothing with blossom, or, in winter, wheeling their bikes through thick snow under the stark black boughs.

But since that day just after the Anschluss, when they had met on the tram, he had seen her less and less. She seemed preoccupied, and she was often busy at weekends. It would be good, Karl thought, to talk to her, to be reassured by her friendship and the special feeling there was between them, to laugh as they had always laughed together.

But when he turned down the gravel path leading to Lisl’s house, Karl saw with dismay, on a brand-new flagpole beside the magnolia tree, a large swastika flag.

He hesitated. Many people flew the Nazi flag, he told himself; maybe her parents felt they had to. There was no way Lisl could be part of the hateful new Nazi Austria.

As soon as she appeared, however, it was plain to Karl that everything had changed. Holding the door only partly open, clearly trying to keep him out, she told him coldly that Austrians like her were no longer allowed to talk to Jews like him.

Karl couldn’t believe what he was hearing. ‘But, Lisl, I’m Austrian too!’ he cried. ‘And you and I are friends–’

‘No, Karl,’ she said, her eyes fixed on a point over his shoulder. ‘Maybe we were friends, but we can’t be any more. It was all a mistake.’ Tossing back her long dark hair, seemingly untouched by his distress, she went on, ‘I didn’t understand before, but my new leader in the Hitler Youth explained it all to us. Jews are enemies of our country. They’re – you’re not wanted here.’

Long afterwards, Karl remembered the stony glint in her eyes, the bitter blow of her words, and the turmoil in his mind as he cycled slowly homewards.

The summer passed, and autumn leaves snowed thickly onto the grey River Danube. Stalls appeared selling spicy hot sausages and roast chestnuts.

Karl was heartsick. In what he increasingly thought of as ‘the old days’, the approach of winter had meant ice-skating with Lisl and his other friends, football with Tommy, visits to the cinema. But he never saw his old school friends any more, and cinemas and sports were forbidden to Jews. And since that dreadful visit to her house, he had heard nothing from Lisl.

Once he thought he glimpsed her in the street, in the Hitler Youth uniform she had told him she would never wear. He tried to forget about her, but the memory of her throbbed like a wound.

At home Rosa asked plaintively, ‘Why can’t we go anywhere any more? Why won’t Annalise from downstairs play with me? Why is everyone so cross and worried?’

No one answered. Instead, Karl’s cousin Tommy brought his little brother Benji, a cheerful toddler, to play with Rosa and keep her amused. Karl and Tommy spent more and more time shut in Karl’s room, making model boats and planes together.

One wintry day, when Karl was walking Goldi beside the Danube Canal, an elderly man approached. ‘Karl?’ he said, ‘Karl Muller?’

It was his former headmaster, Herr Klaar, greyer and more stooped than Karl remembered. As they watched the ducks slipping on the ice, Herr Klaar told Karl that he had been dismissed because of his anti-Nazi views; the maths teacher, Herr Seiss, was now headmaster.

He asked about Karl’s new school. Then he said sadly, ‘I never thought I’d ever have to say this to fellow-Austrians, Karl, but I hope your family are planning to leave the country. It’s very bad for Jews.’

Karl, reassured by his concern, asked the question that had been haunting him. ‘Herr Klaar, why has it all happened? Why do they suddenly hate the Jews?’

Herr Klaar put his hand on Karl’s shoulder. ‘It’s a kind of madness,’ he said quietly. ‘For the past few years, things have been very bad in Germany, and here in Austria too. There were no jobs, there was dreadful poverty, money lost its value … Then Hitler and the Nazis seized power, saying they would put people back to work and make the country strong again.’ He sighed. ‘But they need a scapegoat, and like all bullies

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)