Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

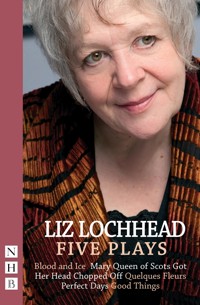

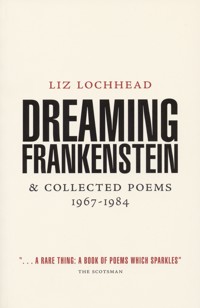

Liz Lochhead is one of the country's leading poets. Her work has paved the way and inspired some of the most inspirational voices writing in Scotland today, including Ali Smith, Kathleen Jamie, Jackie Kay and Carol Ann Duffy. In A Handsel, the first new poems from Scotland's second modern Makar since 2016's Fugitive Colours, the poet celebrates people and those small momentous moments that encapsulate so much of her work. It is human relationships that sit at the heart of these poems; each one is a beautifully realised snapshot that explores the poet's past, her friendships and revisits favourite characters from earlier collections. This landmark publication collects for the first time the poetry of Liz Lochhead. Bringing work back into print, this collected poems publishes all of the poet's collections, presented in their entirety: Memo for Spring, Islands, The Grimm Sisters, Dreaming Frankenstein, The Colour of Black and White and Fugitive Colours, as well as poems from Bagpipe Muzak and True Confessions.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 355

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A HANDSEL

First published in 2023 in Great Britain in Hardback

by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Liz Lochhead, 2023

The right of Liz Lochhead to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 84697 651 3

eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 635 5

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library.

Typeset in Verdigris MVB Pro by The Foundry, Edinburgh

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Bell & Bain, Glasgow

In memory of my father and mother, John and Margaret Lochhead, and my husband Tom Logan

CONTENTS

NEW & UNCOLLECTED POEMS (2023)

Coming to Poetry: An Ode

The Spaces Between

Chimney-sweepers

Found Poem for the Pollen Season

October Equinox

Winter Words

Gloomy December

The Backstory

The Dirty Diva – Though Knocking on a Bit These Days – Nevertheless Attempts to Invent a New Dance Craze

Don’t Go Down the Basement

The Carer’s Song

A Rare Treat

A Handselling for Alice’s Real Wedding

The Word for Marilyn

Ashet

From Beyond the Grave

A Room o My Ain, 1952

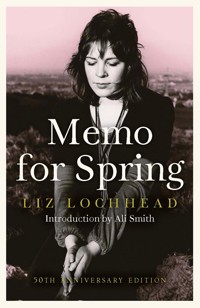

MEMO FOR SPRING (1972)

Revelation

Poem for Other Poor Fools

How Have I Been Since You Last Saw Me?

On Midsummer Common

Fragmentary

The Visit

After a Warrant Sale

Phoenix

Daft Annie on Our Village Mainstreet

Obituary

Morning After

Inventory

Grandfather’s Room

For My Grandmother Knitting

Poem for My Sister

Something I’m Not

Poem on a Day Trip

Overheard by a Young Waitress

Notes on the Inadequacy of a Sketch

Letter from New England

Getting Back

Box Room

Song for Coming Home

George Square

Man on a Bench

Carnival

Cloakroom

The Choosing

Homilies from Hospital

Object

Wedding March

Riddle-Me-Re

Memo to Myself for Spring

ISLANDS (1978)

Outer

Inner

Laundrette

The Bargain

In the Francis Bacon Room at the Tate

THE GRIMM SISTERS (1981)

I. THE STORYTELLER POEMS

Storyteller

2. The Father

3. The Mother

The Grim Sisters

The Furies

1. Harridan

2. Spinster

3. Bawd

My Rival’s House

Three Twists

1. Rapunzstiltskin

2. Beauty & the

3. After Leaving the Castle

Tam Lin’s Lady

Six Disenchantments

II. THE BELTANE BRIDE

The Beltane Bride

Song of Solomon

Stooge Song

Midsummer Night

Blueshirt

The Hickie

The Other Woman

Last Supper

III. HAGS AND MAIDENS

Everybody’s Mother

The Ariadne Version

My Mother’s Suitors

Girl’s Song

The Cailleach

Poppies

The Last Hag

DREAMING FRANKENSTEIN (1984)

What the Pool Said, on Midsummer’s Day

An Abortion

Dreaming Frankenstein

2. What the Creature Said

3. Smirnoff for Karloff

Smuggler

Page from a Biography

The People’s Poet

Construction for a Site: Library on an Old Croquet Lawn, St Andrews

Fourth of July Fireworks

The Carnival Horses

Ontario October Going West

Near Qu’Appelle

In Alberta

Sailing Past Liberty

2. Two Birds

3. My House

4. Inter-City

5. In the Cutting Room

Ships

Hafiz on Danforth Avenue

A Gift

Reading the Signs

Flitting

A Giveaway

Heartbreak Hotel

China Song

Why I Gave You the Chinese Plate

Old Notebooks

Fin

That Summer

West Kensington

The Empty Song

Noises in the Dark

A Letter

Sundaysong

The Legend of the Sword & the Stone

Rainbow

The Dollhouse Convention

In the Dreamschool

2. The Teachers

3. The Prize

The Offering

Legendary

Fetch on the First of January

Mirror’s Song

POEMS FROM TRUE CONFESSIONS (1985 & 2003)

Vymura: The Shade Card Poem

The Suzanne Valadon Story

The Life of Mrs Riley

Favourite Shade

Look at Us

I Wouldn’t Thank You for a Valentine

Men Talk

Condensation

Bagpipe Muzak, Glasgow 1990

THE COLOUR OF BLACK & WHITE (2003)

I.

The Unknown Citizen

The Man in the Comic Strip

In the Black and White Era

Ira and George

The Beekeeper

The New-married Miner

The Baker

II.

Kidspoem/Bairnsang

Little Women

The Metal Raw

Lanarkshire Girls

Your Aunties

Clothes

Social History

After the War

Sorting Through

1953

III.

View of Scotland/Love Poem

Neckties

A Night In

IV.

Epithalamium

The Bride

The Redneck

The Bridegroom

V.

Two poems on characters suggested by Bram Stoker’s Dracula

1. Lucy’s Diary

2. Renfield’s Nurse

VI.

Five Berlin poems

5th April 1990

Aquarium 1

Aquarium 2

Three Visits

Almost-Christmas, the Writers’ House

VII.

Good Wood

Papermaker

A Wee Multitude of Questions for George Wylie

Warpaint and Womanflesh

The Journeyman Paul Cézanne on Mont Sainte Victoire

VIII.

Year 2K Email Epistle to Carol Ann Duffy

Black and White Allsorts

Hell for Poets

Almost Miss Scotland

In the Beginning

The Ballad of Mary Shelley’s Creature

Lady of Shalott

Advice to Old Lovers

Sexual Etiquette

My Way

FUGITIVE COLOURS (2016)

I. LOVE & GRIEF, ELEGIES & PROMISES

Favourite Place

Persimmons

A Handselling, 2006

1. Twenty-One-Year-Old

2. Some Things I Covet in Jura Lodge

3. Cornucopia

4. No Excuse, But Honestly

5. Legacy

Lavender’s Blue

The Optimistic Sound

Wedding Vow: The Simplest, Hardest and the Truest Thing

Anniversaries

A Cambric Shirt

II. THE LIGHT COMES BACK

In the Mid-Midwinter

Autumn with Magpie, Pomegranate

Beyond It

How to Be the Perfect Romantic Poet

III. EKPHRASIS, ETCETERA

Photograph, Art Student, Female, Working Class, 1966

Some Old Photographs

‘The Scullery Maid’ & ‘The Cellar Boy’

1. The Scullery Maid Speaks

2. The Cellar Boy Speaks

The Art of Willie Rodger

A Man Nearly Falling in Love

In Alan Davie’s Paintings

Three Stanzas for Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Labyrinth

Email to Alastair Cook

The Ballad of Elsie Inglis

Gallimaufry

Way Back in the Paleolithic

IV. KIDSPOEMS AND BAIRNSANGS

How I’ll Decorate My Tree

Glasgow Nonsense Rhyme, Nursery Rhyme, for Molly

Nina’s Song

In Gaia’s Poetry

The Fruit of the Word

V. MAKAR SONGS, OCCASSIONAL AND PERFORMANCE PIECES MAINLY

Poets Need Not

Connecting Cultures

Random

Open

Spring 2010, and at His Desk by the Window Is Eddie in a Red Shirt

When the Poem Went to Prison

Listen

The Silk Road

In Praise of Monsieur Sax

Grace

Lines for the Centenary of the Scotch Whisky Association

From a Mouse

The Theatre Maker’s Credo

In Number One Dressing Room, A Portrait of the Leading Actress

Nick Dowp, Feeling Miscast in a Very English Production, Rehearses Bottom’s Dream

Epistle to David

Portait of a Gentleman at Sixty

Address to a Septuagenarian Gentleman at Home

For Myra McFadden on her Sixtieth Birthday

Song for a Dirty Diva

Another, Later, Song for that Same Dirty Diva

In Praise of Old Vinyl

Index of Titles

NEW & UNCOLLECTED POEMS

(2023)

COMING TO POETRY

An Ode

Reading you, John Keats, at seventy I hurt

pierced again by your beauty that is truth,

was truth to me and my fourteen-year-old heart.

Knowing nothing of nightingales, my melting youth –

still blind to the perfection of a Grecian urn,

deaf yet to Darien, Homer a closed book –

burst open to ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’.

This night my thoughts return

to that seeming simple-as-a-song ballad, to what it took

to have me come to poetry.

My joy forever? My truth and terror too.

This was the Cuban Missile Crisis, October ’62.

In English, last week we’d finished St Agnes’ Eve.

Next week, nuclear obliteration is due

unless there’s a Khrushchev climb-down they don’t believe

will happen. Countdown to doom.

Mr Valentine read us ‘La Belle Dame’ and into the room

came yon knight at arms, so haggard and so woe-begone

with the lily’s pale anguish on his brow,

on his cheeks the rose fading, withering like our Now.

Was it to be all over and done

our nineteen-sixties sweetness scarce begun,

my warmed jewels never to be unclasped one by one,

my fragrant bodice never loosened, nor by degrees,

my unbuttoned garments fall rustling to my knees?

Oh I longed as I had never longed before

for my wild eyes to be closed, just once, with kisses four.

I couldn’t sleep that night.

For next week we might

we really might, like you, poor dear John Keats, be dead.

I remember this so vividly I’m there

feeling again that middle-of-the-night deep dread,

standing looking out that window in the hall to where –

perhaps soon to be just gone, not here –

under the blueish lamplight our ordinary street

lay weirdly stilled and strange, like a Magritte

out of that art book off the school library shelf.

In my parents’ room someone else not sleeping stirs –

we’re all scared but you’ve to keep it to yourself.

Though day by day I see those wee tells betray their fears,

how they’d looked at each other, nothing said,

when Kennedy addressed his Nation. A blockade.

Now, hourly, when the news comes on I know

by their clenched attention to the radio . . .

It didn’t happen. I am still alive,

still hunger for poetry, for life.

You never got to take sweet, silly, loving Fanny Brawne to wife,

John Keats, while I, who never thought to survive

into my beldame-years, must needs be stoical at seventy.

My Tom, dear husband of my heart, taken from me

and from this life he loved, an astonishing ten years ago.

I’m here. Birds still sing. Sometimes. I know, I know

I must try not to yearn

for all the sweetnesses gone and past return.

THE SPACES BETWEEN

for Leslie McGuire

The boy is ten and today it is his birthday.

Behind him on the lawn

his mother and his little sister

unfurl a rainbow crayoned big and bright

on a roll of old wallpaper.

His father, big-eyed, mock-solemn, pantomimes ceremony

as he lights the ten candles on the cake.

Inside her living-room

his grandmother puts her open palm to the window.

Out in the garden, her grandson

reaches up, mirrors her, stretching fingers

and they smile and smile as if they touched

warm flesh not cold glass.

More than forty thousand years ago

men or women splayed their fingers thus

and put their hands to bare rock. They

chewed ochre, red-ochre, gritted charcoal and blew,

blew with projectile effort that really took it out of them,

their living breath.

Raw gouts of pigment

spattered the living stencil

that was each’s own living hand

and made their mark.

The space of absence

was the clean, stark picture of their presence

and it pleased them.

We do not know why they did it

and maybe they did not either but

they knew they must.

It was the cold cave wall

and they knew they were up against it.

The birthday boy is juggling.

He has been spending time in the lockdown learning

but though he still can’t keep it up for long

his grandmother dumb-shows most extravagant applause.

She toasts them all in tea

from her Best Granny in the World mug, winking

and licking her lips ecstatically as,

outdoors, they cut the cake,

miming hunger, miming

prayer for her hunger to be sated.

The slim girl dances

and her grandmother claps

and claps again, blinking tears.

Another matched high-five at her window.

Neither the blown candles nor the blown kisses

will leave any permanent mark

– unless love does? –

on them on this the only afternoon

they will be all alive together on just this day the boy is ten.

CHIMNEY-SWEEPERS

Maytime and I’m

on a fool’s errand

carrying home this bunch of the dandelion clocks

which Shakespeare called chimney-sweepers

and a friend tells me his wee grand-daughter

in the here-and-now calls puffballs.

I’m holding my breath, and them, this carefully

because I want to take them home and try

to paint them, although

one breath of wind and in no time

I’ll be stuck with nothing but a hank of

leggy, limp, milky pee-the-bed stalks

topped with baldy wee green buttons, for

golden lads and girls all must

as chimney-sweepers come to dust.

On daisy hill by the railway bridge

one lone pair of lovers laze in the sun.

A little apart from her, he lounges

smoking a slow cigarette and waits

smiling, half-watching her weave a bluebell chain

that swings intricate from her fingers, hangs heavy

till she loops it, a coronet upon her nut-brown hair.

I’m wondering is this to be her something blue?

She calls out to me, I to her,

as folk do in these days of distancing

and I can hardly believe it when she says

she never in all her childhood

told the time by a dandelion clock.

She’s up to her oxters in ox-eye daisies, this girl.

The ones my mother, Margaret,

always called marguerites but never

without telling me again how my father

writing to her from France before Dunkirk or after D–Day

always began his letters Dear Marguerite.

The saying goes that a maiden

crowned by bluebells can never tell a lie

the girl informs me, solemn as she

crosses her fingers, each hand held high.

The smoke from her lover’s cigarette is

almost but not quite as blue as

the frail blooms – time, truth and a promise – that

she’s braided together on this their one-and-only

sure-to-be-perfect summer’s day.

Oh Marguerite Margaret my Mum

who never got to be as old as I am today

did you ever hear tell of this proverb?

Oh Mum how much I wish I could ask you

this and so many other

small and silly things, but

golden lads and girls all must

as chimney-sweepers come to dust.

FOUND POEM FOR THE POLLEN SEASON

Slender foxtail grass

Yorkshire fog

silvery hair grass

floating club rush

silky bent grass.

barren brome grass.

Meadow soft grass

Marram grass

sweet vernal grass

mountain melick

loose sedge.

great panicled sedge so

easily

Blue moor grass

mistaken

sea hard grass

for japanese blood grass.

glaucous sweet grass

bearded couch grass

Lyme grass

common quaking grass

wood millet grass

switchgrass also known as

sheep’s fescue

great panic grass

wall barley

perennial rye grass

wild oat

pendulous wood sedge.

darnel.

OCTOBER EQUINOX

Wild,

wild weather, that ragged crow blown across the road like

a scrap of ripped old black binbag and every time the wind drops

the air full of the roar of the rut, each maculate leaf

a leopard changing its spots

WINTER WORDS

brave snowdrops on the ground

scant snowdrops from the sky

a wishbone on the windowsill

GLOOMY DECEMBER

These are the shortened days

and the endless nights.

– Carol Ann Duffy, from Mean Time (1993)

Gloomy December.

The doldrum days of the dead of winter.

These are the shortest days

and the endless nights.

So wish for the moon

and long for the light.

Chill winds. Relentless rain.

Dark to go to work in, darkness home again.

But, given just one fine day of sun and sharp, clean frost,

our lost, maybe long-lost

faith – if for nothing more than the year’s turning –

comes back like the light comes back.

A promise in our bleak midwinter yearning

once in a rare and clear blue noon

if we wish for the moon.

Till then, the light’s soul and spirit

is locked in its absence,

and our longing for it.

Whether you believe with the Magi in their miracle –

Three Kings bow down low before the Child of Light –

or whether we think them Wise Men on a fool’s errand,

their gifts useless, magnificent, precious,

who came following one star and its faltering gleaming

till they came to the place,

it was a brave as well as a cold coming.

Yes.

And whether it was a refugee waif

or the Saviour that was born,

whether some shepherds on the night shift

saw angels, or a meteor storm,

believe in the light’s soul and spirit

that’s in its absence

and our longing for it.

THE BACKSTORY

This woman, she’s about seventy-ish,

mibbe even seventy-four or five.

I think her name is Arlene.

Yes, she’s Arlene, that feels right.

Well, Arlene got married

married far too young, to Malc

way back at the end of the sixties.

Arlene hasn’t seen Malc –

not face to face,

since they got divorced way back in 1977.

None of a family, thank God,

bad enough splitting up without the complications.

Back then Malc was in a band –

lead guitar and vocals.

Malc was the band.

That voice of his

so distinctive.

The solo career

after the band split up a

couple of years later didn’t

really take off as predicted, though.

But it was

a successful band at the time – very,

all over the UK and in America

not just here in Scotland.

A kind of country-rock crossover

with, they liked to say, Celtic roots.

A band that was always on the road.

When Arlene came down this morning

The Herald was on the table open at the page.

Her husband Tony,

her husband of the best part of forty years,

Tony must have left it open like that for her

when he left early this morning

for his regular Thursday golf with the cronies

he’s been doing every week since he retired.

So this morning Arlene read the

Obituary of Malcy Torrance of

iconic Scottish Seventies rock band Lovers Leap.

And she found herself going up the stairs,

getting her notebook out.

She’s always kept one – even way back.

Malc even used to pinch wee lines out of Arlene’s notebook,

muck about a wee bit with them here and there,

turn them into the lyrics of the songs he wrote with the band.

Not that she got the credit.

Not that she ever minded.

Over the years, Arlene’s

scribbled down a lot of stuff.

This and that – just putting into words

odd wee things that’ve struck her.

Who knows where they are now, half

these old notebooks of hers, and, no, she never

meant to stop writing things down,

but, recently, somehow

she’s just not had the time.

Granted she has been busy with the grand-weans –

although, actually, Arlene’s glad

for the pair of them be asked to do

what Tony’s always saying is

a good bit mair than their fair share of the looking-eftir.

Anyway, this morning Arlene’s got

her old notebook and biro out

and I can just see her now,

still in her pyjamas,

her coffee getting cold and her not caring,

scribbling away with hardly any scoring out.

Some people write Country and Western songs? Well,

I suppose this is what you could call a

Country and Western story.

And it goes something like this:

Once upon a time and it wisnae yesterday

his pals aw thought I was a catch

and my maw and all my aunties

thought I’d really won a watch

and we looked each other in the eye

sure we’d really met our match.

Oh, if we could only mind how right it was

before it went so wrong

this would be a song with a story

and this’d be the story of that song.

Our split

never hit the headlines – didn’t require the National Enquirer

to speculate on the reasons

why it all went adrift with the shift of the seasons.

wasn’t a Doesn’t-Count-on-Location –

tho shit happens on the road.

It wasn’t about what you put your dick up

or what you put up your nose

wasn’t like the penny dropped when

you got out the van with a sheepish smile

and that single red rose . . .

wasn’t as if I threw your guitar out the window

or cut up your clothes

no, I never packed your suitcase

and left it in the hall

called time on us and called a lawyer –

no that wasn’t it at all.

Oh, if we could only mind how right it was

before it went so wrong

this would be a song with a story

and this’d be the story of that song.

Wasn’t about what we were open about

or what we – wisely – kept hid.

Doesn’t-Count-on-Location?

I think you’ll find it did.

But we

never ever accused each other of

only wanting each other

on our own terms.

Wasn’t as if we didn’t know an open marriage

was an open can of worms.

Wasn’t as if we stopped trying –

we tried constantly.

You never hit the bottle

you never hit me.

Wasn’t as if we stopped talking.

We never lost it in bed.

But something ’bout us being together

really fucked with my head

and whatever it was stopped me wearing my wedding ring

whatever it was it wasn’t

the usual thing

and I suppose I’ll always remain in the dark

about what threw me into the arms of that guy at work.

Oh, it wasn’t that, not any of that,

but this much is true

I’d never forgive myself if I couldn’t

forgive me and you.

For if I could only mind how right it was

before it went so wrong

this would be a song with a story,

and this’d be the story of that song.

THE DIRTY DIVA – THOUGH KNOCKING ON A BIT THESE DAYS–NEVERTHELESS ATTEMPTS TO INVENT A NEW DANCE CRAZE

Can’t get my socks on

can’t get my rocks off

but that loss of libido

that everybody talks of

is yet to kick in.

Let’s do the Salsa Geriatrica –

It’s no sin.

Jeepers creepers

The Grim Reaper

for crying out loud

he’s cutting a cruel swathe

through the Old Crowd.

he’s on the rampage!

so what we gonna do

with our Late Middle Age

except the Salsa Geriatrica –

It’s no sin?

There are those

God knows

think at Our Age it’s

Not Right

never ever play

their ‘Lay, Lady Lay’,

their Marvin Gaye

nor their Barry White . . .

I say c’mon, c’mon, c’mon give it a spin –

let’s try the Salsa Geriatrica –

it’s no sin.

Try it on with

some septuagenarians and they go:

Gie’s peace!

They’re like: I’m glad I’m past it, it’s

A Merciful Release.

Me? I’m still like:

Get ready, get set, begin

the Salsa Geriatrica!

It’s no sin.

Had we but world enough

and time

pro-crastination

were no crime . . .

But

unless the whole idea’s

totally horrendous – or (worse!) risible –

delay is inadvisable.

At our age.

Are we on the same page?

What else we gonna do with our

Late Middle Age?

DON’T GO DOWN THE BASEMENT

PROLOGUE

The Festival Theatre, Edinburgh. A touring musical.

Cheap seats, Girls’ Night Out, no bad at all . . .

OK, The Buddy Holly Story wasnae the greatest ever told

but the songs are good, and watching it unfold

the audience are all wishing we could avert disaster

and somehow Buddy could rave on wi his Stratocaster

and play the morra night’s gig in Mason City.

Not to be, and more’s the pity.

Raither than thole

another four-hundred mile

in an auld school bus wi nae heater

Buddy charters yon plane, a rickety four-seater.

True, thon ‘Winter Dance Party Tour’ was the Tour from Hell,

but when bad-stuff happens, we ken very well

The protagonist aye brings it on hissel.

Thus, in a white-out in a cornfield in Iowa, there came a cropper

Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper.

PART ONE

Aye, we were all like: Don’t do it!

Buddy, just don’t get on that plane

Can you no take a telling?

Well, I’ll no tell you again.

The young wife tellt you to think on, Buddy

so could you no have bloody thunk?

It was snawin like fuck, the propeller fell aff

and the pilot was drunk.

If your name happens to be Kennedy

remember who you are

and dinnae go bowling doon boulevards in Dallas

in an open-top car.

A beautiful, beautiful white boy

with a beautiful black-man’s voice, that was Elvis.

With one swivel of your blue suede shoes,

with one thrust of your pelvis

sex enters, on TV, the living rooms of America.

Pure Sex – that’s the song you sing!

It’s vital, it’s whole, it’s rock and roll

and Elvis you’re the King.

But oh, Elvis! Your doctor in Graceland

was a bloody disgrace.

You ended up, forty-two year auld, ballooned, bloated

dead on the toilet – but still off your face

on pre-scription drugs. Oh no! Don’t

go to the chemist. Don’t let them fill

that bloody prescription the bastard wrote you

DO NOT TAKE THAT PILL

it’s probably worse than street heroin –

Pills Will Kill . . . So many, before and since.

I’m thinking: Judy Garland, Marilyn,

Jim Morrison, Michael Jackson . . . Prince –

but hey, if a girl wants to be a Princess

deal is: become some Royal’s wife.

But if he sniggers and says whatever ‘in love’ means

run for your life;

for that’s not an auspicious beginning

for the so-called stuff of fairytales.

It’ll jist get worse and worse till it’s divorce

for the Prince and Princess of Wales.

And PS – Diana and Dodi, if you will deny

the bloody paparazzi their photae

mibbe a speed-freak drunk an coked oot his heid

isnae the best chauffeur to go tae?

PART TWO

The Greeks said Tragedy was jist like the thing

whereas Comedy required the bending

of the plot as it unravelled

to an – unlikely – happy ending.

In his Poetics, Aristotle said: Our fear and pity

for the tragic hero and tragic action

calls up the cleansing horror of Catharsis

and brings a certain satisfaction

as Hubris leads inevitably to Nemesis –

aye, when it came to the bit

thae Greeks aye had a word –

or two – for it.

But enough of all thae technical terms.

I cannae be annoyed

thinking up whit’s the Scots

for schadenfreude? –

Oedipus, did your Maw nor your Paw no tell you

to body-swerve the Oracle? Oh dear,

Oracles very seldom tell you

whit you wanted to hear . . .

Ariadne, by all means snog Theseus

afore he goes into the Labyrinth to kill the Minotaur.

Somethin tae put a bit o heart in the boy?

But dinnae go too faur

an betray your mither an faither

wi thon fatal ball o wool

’n then forget to cheynge the black sails tae white!

Ach, Theseus ’n Ariadne? Not cool!

Jason, don’t underestimate Medea.

She’ll make you wish you’d never been born

faur less ever bairned her.

Hell had nae fury like that wummin scorned . . .

PART THREE

Aye, there’s minny a fond attraction

proves fatal, push comes to shove.

Romeo an Juliet,

dinnae fall in love.

Plus there’s poor auld King Lear

who’s no aw there.

Three daughters?

Ends up oot on his ear?

Then there’s the wan where pure evil Iago manipulates

poor jealous Moor o Venice, Othello.

There’s the wan wi the pushy wife that kills the King –

you’re no supposed to say his name out loud! Scottish fellow . . .

But of all Shakespeare’s protagonists

to whom tragic fate did befall

surely Hamlet, Prince of Denmark

was the daddy of them all?

Eftir what his Feyther’s Ghost revealed, you’d think

revenge would be . . . in with a shout?

Naw. Procrastinating Hamlet would gie everything

the benefit of the doubt.

Nor can we ignore how, in all Elsinore

from commoner to king,

every bugger could be depended upon

to dae exactly the wrang thing –

not only embark on a dodgy course of action,

but go oan wi it jist to keep up a front.

Gertrude, dinnae mairry Claudius,

the man is a cunt.

Ophelia? Oh, of course he did!

Mair than wance, then blamed it on you.

You were too young, too busy pickin flooers

to ken that’s jist whit men do.

Polonius, your platitudes are tedious.

You’re mibbe tryin tae be helpful, but, please,

if you will hide and eavesdrop ahint the arras

don’t bloody sneeze.

OK, a Feyther’s murder demands Revenge.

But, Laertes, dinnae hotfoot it back fae France

or you too will end up deid-er

than Guildenstern or Rosencrantz

whit wi yer sister Ophelia droonin hersel

when the pair sowell was no the full shilling

an then the hail thing escalating intae

a pure orgy o killing

wi first of all Hamlet’s Mammy Gertrude drinking,

accidentally, from thon poisoned cup –

oh, and Laertes, if you will also poison yer sword-tip

don’t get yer foils mixed up.

But at least you clyped on Claudius furst.

And that was the end. Finished.

Hamlet, dying, forced him to drink the dregs, ran him through with his sword,

till at last he expired, his villainy punished.

Hamlet, you did think – and think again – afore acting.

Did it help you? No wan bit.

Mibbe if shit is determined to happen, it will?

This is it.

THE CARER’S SONG

Lyrics written early in Covid pandemic lockdown 2020, to be sung by Glasgow’s Carol Laula in honour of the nurses, auxiliaries and care-home workers from all over the UK, and, especially, in loving memory of John Prine, the great songwriter and chronicler of blue-collar America who died of the disease that year. It borrowed the tune of Prine’s ‘Angel from Montgomery’.

I am just a wummin who works as a carer

wish life was fairer but God knows it’s no.

I’ve aye been a grafter it’s ma job to look after

them that’s never had nuthin, or were Really Somebody no long ago.

I’m no an angel I’m no a hero

tho yez clap on a Thursday till your hauns are aw sair.

Every day I face up to what we’re aw feart o

just respect me protect me mibbe pey a bit mair?

I don’t make a fuss I just get on two busses

for I live in a hoose, aye but I work in a Home.

I’ve to no think twice jist follow th’advice

from thae bliddy clowns that it’s hard to take it from.

Thon lot? Don’t start me it would break your heart, see

wi even less PPE than the NHS

they think it’s just fine that we’re on the front line

ach, it is what it is. An what it is is a mess.

I am no an angel I am no a hero

yez clap oan a Thursday till your hauns are aw sair.

Every day I face up to what we’re aw feart o

so respect me protect me mibbe pey a bit mair?

Ach, you’re all right, ma honey let’s get you comfy,

clean you up lovely ma darlin, OK?

Please test us for Covid – I’m just bliddy livid

– Are ‘dignity’ and ‘humanity’ just empty words they say?

I am no an angel I am no a hero

tho yez clap oan a Thursday till your hauns are aw sair.

Every day I face up to what we’re aw feart o

so respect me protect me mibbe pey a bit mair?

Mibbe think first, eh? Worst comes to the worst

it’ll be me that has your loved one’s dying hand to hold.

Should they require us to fight this virus

wi nothin but a binbag apron and a perra Marigolds?

I am no angel I am no hero

that yez clap oan a Thursday till your hauns are aw sair.

Every day I face up tae what we’re aw feart o

so respect me protect me mibbe pey a bit mair?

Respect me protect me mibbe pey a bit mair.

Respect me protect me

mibbe pey a bit mair.

A RARE TREAT

for Brian O’Sullivan

‘Had a good morning this morning,’ says Brian, ‘I wrote a song.

The Young Man’s Mother sings it to him,

I think it’s OK. It moves the plot along.’

‘Like any song worth its salt in a musical?’ say I,

Wondering will he sing me it?

He smiles, explains it’s actually too high

For him, scored as it is for the Young Man’s Ma –

But, though he’s not got all the last verse yet,

Here’s the story so far . . .

I’m not getting any vibes from him of

Fools and bairns should never . . .

Which is how I get to be this song’s first audience.

Ever.

My talented pal!

A musical!

Music and Lyrics – and he wrote The Book.

It’s from The Clouds by Aristophanes,

Some Old Comedy he took,

Adapted.

This song?

The Loving Mother Character sings her son’s name,

Again, again

‘Pheidippides! Pheidippides!’

And these odd Greek syllables

Somehow make the catchiest refrain!

Brian my pal, sing me, please, the bit

That’s not quite ready yet

In lyricist’s ham and eggs?

Because it’s obvious just how brilliant it is going to be.

This song has legs.

A HANDSELLING FOR ALICE’S REAL WEDDING

for Alice Marra and Colin Reid

Who is it walks you down the aisle, Alice?

Love, love walks you down the aisle,

the love that’s loved you

since you were the wee-est girl.

So smile!

Smile, Alice – all this wedding’s tears

are have-no-fear tears,

are mere tears of joy

to see the best girl marry exactly-the-right boy.

Who waits with you, Colin,

as you wait for your bride?

Love. The love that’s loved you always

stands by your side

so stand by it, Colin, stand

and wait till love, your Alice,

comes to take your hand.

THE WORD FOR MARILYN

In memory of Marilyn Imrie, 1947–2020.

When you come to me in dreams, Marilyn,

as sometimes since you died you do but always

in dreams exactly as you were in life.

And whatever mad incoherent

other stuff might’ve gone on in that dream with its

chaotic constant metamorphosing cast

and drenching emotions entirely inappropriate for

whatever seemed to be happening

in its daft ever-shifting surreal dream-plot

if

I had a dream last night and you were in it,

Marilyn,

when I wake up I’m sad of course

but beyond that the

continuing calming comfort of your presence

pervades my day.

We were exactly the same age as each other

with wintry birthdays only one month apart

and today already it’s the second birthday

you didn’t get to celebrate.

Oh Marilyn,

our friendship goes back to our early thirties

and I can’t remember what work thing it was

cemented our friendship –

something at the BBC at Queen Street for radio

and it won’t have been a play, not then

not in the very early, early eighties – but whatever it was

that friendship was as

instantaneous as it was deep and firm and true.

Yes, we were over thirty,

Marilyn,

Women of the World and Girls About Town

searching for something we didn’t know

if we believed was even possible –

a lasting love, a

till-death-do-us-part love.

Before the decade was over – but barely –

for each of us such a love

found us.

Whenever I’d think of those

spare, short, six lines

by Raymond Carver:

Late Fragment: And did you get what

You wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

Beloved on the earth.

In my mind, Marilyn, I’d hear

you say these words

because I know you could have, would have, said these words

and meant them.

And this was the best comfort I could get

as I’d berate myself about how these

last few weeks I’ve been

looking out of windows, not thinking

just waiting for it to come to me,

please, the just-one-word

that’d sum up Marilyn as together

we all remember her.

Most days I’d get nothing –

another dreich skyline

or another gorgeous pink-striped winter dawn to gawp at

and still coming up with nothing –

but finally it came to me, it’s

lovingkindness, Marilyn.

Yes, it’s lovingkindness all-one-word, no-hyphen.

That’s you. That’ll do.

And of course it probably wasn’t

a poem by Raymond Carver –

although indeed it says it all.

It was what it was – maybe it’ll have been

a late fragment someone will have

found among his papers, titled it in all honesty,

and simply typed it up?

When anyone asks me

How long was it you and Marilyn Imrie

were such good friends?

I’ll try and use a little lovingkindness as –

leading by example in the Marilyn manner –

I’ll try to gently correct them, I’ll

change past to present tense as I answer

Oh, Marilyn and I,

we’ve been friends for over forty years

and counting.

ASHET

On yon Zoom

the ither day a wee bit friendly argie-bargie stertit up

aboot whit exactly wis

an ashet

when it wis at hame? Well, some wid huv it

it wis a muckle-great delft platter for servin,

say, a hail gigot o mutton roastit wi aw the trimmins

an ithers insistit naw it wis nuthin but a

humble enamel pie-dish

sich as ye’d mibbe mak a shepherd’s pie in or yaise

for reheatin (o aye, in a gey hoat oven!)

yesterday’s left-ower stovies or day-afore-peyday pan-haggis

(never ever cryin that skirlie, nut ata,

no here in Glesca, no in the West).

There’s monie wouldnae gie houseroom

to this shabby aul chrome-platit slottit-spoon

wi hardly a scrap o rid or black pent left on its widden haunle, but –

it was ma mither’s – I haud it in ma haun wi ma

heid fu o mince an reminiscence, thinkin

how a clock could be a clock or a black beetle

how a sair heid is a sair heid but a sair haun is

a piece an jam

as lang’s the slice o white breid’s as thick as a doorstop

an the jam strawberry or rasp (the blood, the bandage) an I’m

wonderin

– since the press in ma kitchen contains

baith a chippt bog standard wee white pie-dish an thon

oval antique art-nouvea losol-ware tulip servan-dish

I got for a shillin in a kirk jumble-sale in the sixties –

pie-dish or platter? Which is the classic ashet?

Och, settle an argument with a friend, wee bit o

elementary detective work in a dictionar, an here it

turns oot it’s no either/or but baith/and

which is even better – for mair is ayeweys mair than less

in ma book, eh no?

An I’ll tell ye wan thing for shair: ma brand-new winterdykes

I ordered online an that arrived the day fae Amazon

might no be made o wid but raither

o clean plastic an lightweight metal

an huv an awfy well-designed an nifty wey

o foldin doon tae nuthin to store gey neatly in the loaby press

or o openin oot lik wings

and takin a loat mair claes than ma pulley ever could

but they’ll aye be ma

winterdykes.

FROM BEYOND THE GRAVE

Jenny Clow, young maidservant to Nancy McLehose & frequent bearer of secret letters between Clarinda and Sylvander, delivers a heartfelt if anachronistic ‘#Me Too’ to Robert Burns . . .

‘What luxury of bliss I was enjoying this time yesternight! My ever-dearest Clarinda, you have stolen away my soul: but you have refined, you have exalted it; you have given it a stronger sense of Virtue, and a stronger relish for Piety . . .’

Robert Burns to Mrs Agnes McLehose, his Nancy, early in their passionate, if physically unconsummated, love affair, Edinburgh, January 1788

‘—I, as I came home, called for a certain woman – I am disgusted with her; I cannot endure her! I, while my heart smote me for the profanity, tried to compare her with my Clarinda:

’twas setting the expiring glimmer of a farthing taper beside the cloudless glory of the meridian sun. Here, was tasteless, insipid vulgarity of soul and mercenary fawning; there, polished good sense, heaven-born genius and the most generous, the most tender Passion . . .’

Robert Burns to Mrs Agnes McLehose, on his reunion with Jean Armour, Mauchline, 23rd February 1788.

‘Jean I found banished . . . forlorn destitute and friendless . . . I have reconciled her to her fate, and I have reconciled her to her mother . . . I have taken her a room . . . I have taken her to my arms . . . I have given her a mahogany bed. I have given her a guinea and I have fucked her till she rejoiced with joy unspeakable and full of glory. But, as I always am on every occasion, I have been prudent and cautious to an astonishing degree. I swore her privately and solemnly never to attempt any claim on me as a husband even though anybody should persuade her she had such a claim (which she had not), neither during my life nor after my death. She did all this like a good girl, and I took the opportunity of some dry horse litter and gave her such a thundering scalade that electrified the very marrow of her bones. Oh, what a peacemaker is a guid weely-willy pintle! It is the mediator, the guarantee, the umpire, the bond of union, the solemn league and covenant, the plenipotentiary, the Aaron’s Rod, the Jacob’s Staff, the sword of mercy, the philosopher’s stone, the Horn of Plenty and Tree of Life between Man and Woman.’

Robert Burns to his younger Edinburgh friend, Robert Ainslie, 3 March 1788.

Great lover? Rab, you wrote your ain reviews!

Did you believe in a wummin’s right to choose?

For aw we ken t’wis never in Jean’s gift to refuse

Thon ‘electrifying scalade’.

She micht have got up, rolled her een, an hauf-amused

Muttered, ‘no bad’.

Floored, there’s minny a lass discovers

The brute hard-at-it buck rootin above her’s

Quite shair he’s the last o the rid-hoat lovers,

God’s gift! –

Tho the delusion he’s th’greatest o earth-movers

Be frankly daft!

An wha kens whit Jean Armour was feelin?

Mibbe aw yon ‘ecstatic’ yelping and squealin

In rising crescendo, had raither been revealin

No pleasure but pain?

Desertit, eight-month gone, long past concealin . . .

An twins. Again!

Rab, you dearly lo’ed a bit o posh an chose

Your ‘Clarinda’, the married Mistress McLehose

Frae ’mang Edinburgh’s those-and-sich-as-those.

Tho you persisted –

(Poems, promises, billets doux) – tried everythin, God knows,

Still she resisted.

Silly, camp, fause names! I suppose I do admire

Th’attempt at secrecy? Why the hell tho did she require

Me to ‘await the response’ she was on fire

To receive from ‘her Sylvander’.

Mair than his hauns, his pent-up desperation an desire

Did wander . . .

Ach, minny a swain faced thus wi nothin-doin

Indulges elsewhere in expedient rough-wooin

While some random other recipient o what’s ensuin

Accepts her fate

An for the moment he disnae care if wha he’s screwin

’S a mere surrogate.

He was mad wi lust for my chaste mistress. Nothing worse.

Really wanted her, she wouldnae. I did. My curse?

I thought he fancied me. Quite the reverse

I fear.

Jist made for his ‘guid willy-pintle’ a handy silk purse

O my soo’s ear.

Twentieth-century folk thought ’twas their invention,

Birth-control! And granted Rabbie an exemption –

But afore Dutch caps, rubber johnnies, no to mention

Game-changin pills

There existit an obvious method o prevention

As auld’s the hills . . .

Nae wey o avoiding pregnancy? Oh please!

Tell that tae the birds an bees

Minny a lover and his lass took post-orgasmic ease

’Mang th’ hermless spatters

O a skillfu cocksman blessed wi expertise

In country matters.

I had to keep Mum ’boot Sainted Rabbie

Wha fucked like a poet, in Standard Habbie.

Quick, staccato an jab-jab-jabby

Then – oof, past carin

Let fly, an left me – is yon no jist fab, eh? –

Haudin the bairn.

He made promises that meltit like snaw

Clarinda got the song, I got hee-haw

’Cept the bairn, a faitherless yin an aw –

Rab, you could’ve easily,

If you cared aboot a lass at a

Have got aff at Paisley!

A ROOM O MY AIN, 1952

The King Is Dead, Long Live the Queen.

Little children should be seen

and not heard

in nineteen fifty-two

I’m four year-auld – we’ve just got word

we’ve got a Scottish Special house

the three of us –

Me, my Dad and my Mum –

oh they’ve been waiting and waiting

thought they’d still be waiting till kingdom come

for their ain hoose

for a hoose o their ain.

At first it was none of a family yet

then jist the wan wean, an aye she’s an Only One

now at last their life has just begun –

been eight long year since

in my granny an granda’s front room

they got married in uniform, nae honeymoon

(it’s a story I’ve heard before

about the no-picnic that was the war) –

now life will never be the same

in Mum ’n’ Dad’s first-ever married hame.

Nae mair jammed, nae mair crammed

in wi the inlaws, one set

then the ither, sharing a kitchenette

steyin in the wan back room