Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Modern Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

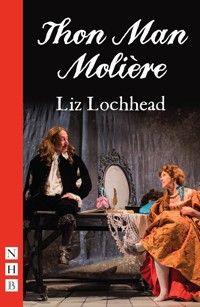

'Why do folk not, ever, catch on to themselves?… Ach, gies you another interesting nutter to play.' Welcome to Paris at the time of Louis XIV. Come backstage and meet the King's theatre company – a troupe of grandes dames, old hams, ingénues and, of course, their leading man, author of their dramas and cause of all their troubles... thon man Molière. Under constant threat of debtors' prison, in big bother with church and state and – worst of all – disastrously in love, Molière writes brilliant, scurrilous comedies inspired by a desperate life. But telling the truth is a dangerous business and his latest drama could be the death of him… Liz Lochhead's play Thon Man Molière was first performed at the Royal Lyceum Theatre Edinburgh in 2016, in a production starring Jimmy Chisholm and Siobhan Redmond. 'I was so moved by this play, which surprised me, as I had expected a knockabout comedy. Don't get me wrong, it was funny. But I hadn't expected the tenderness and emotional complexity. The bond – eternal, exasperated, essential – between Molière and Madeleine is the core of the piece, but all of these characters seem every bit as human and deep and strange and needy as theatre people always are.' David Greig, Artistic Director of the Royal Lyceum, Edinburgh

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 121

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

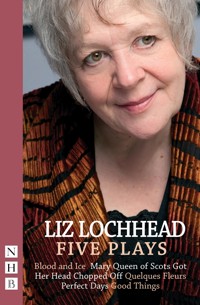

Liz Lochhead

THON MANMOLIÈRE

orWhit Got Him Intae Aw That Bother

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Original Production

Introduction

Dedication

Characters

Thon Man Molière

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Thon Man Molière was first performed at the Royal Lyceum Theatre Edinburgh on 20 May 2016, with the following cast:

MOLIÈRE

Jimmy Chisholm

TOINETTE

Molly Innes

MADELEINE BÉJART

Siobhan Redmond

MENOU

Sarah Miele

GROS-RENÉ DU PARC

Steven McNicoll

THÉRÈSE DU PARC

Nicola Roy

MICHEL BARON

James Anthony Pearson

MATHURINE

Leigh Simpson

Director

Tony Cownie

Designer

Neil Murray

Lighting Designer

Chris Davey

Composer

Claire McKenzie

Introduction

Liz Lochhead

Thon Man Molière: or Whit Got Him Intae Aw That Bother is about one of my great theatrical heroes. It was informed and inspired by Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Life of Monsieur de Molière, his meticulously researched but very personal, very vivid, take on the man. It was written in 1932 but not published until 1962, more than twenty years after its author’s death, for, under Stalin, Bulgakov’s Molière biog, like most of his plays and novels, was met with perilous disapproval and banned by the Soviet authorities, detecting parallels being drawn between Molière and Bulgakov himself, judging it unacceptably riddled with veiled criticisms of their own repressive post-revolutionary society and times.

It must be at least a dozen years or so ago that a copy of this Bulgakov biography was given to me by my great friend, the master of the short-story, Helen Simpson, saying she felt I was going to some time write a play about Molière. I found it a really great read, vivid as any novel, but didn’t see anything in her prediction. It was years later I was struck suddenly by the parallel between Molière and our contemporary artist in comedy, Woody Allen, and the scandal that ensued when Mia Farrow found those infamous Polaroid photographs taken by Allen of her adopted daughter, Soon Yi. Shame there wasn’t such a thing as photography in Molière’s time…

Then I thought: ‘Ah, but I think I know exactly how to get around that!’ From then on I had a scene, once I had a scene that was it. I was writing this play.

Madeleine Béjart and young Jean-Baptiste Poquelin de Molière were briefly lovers. Then partners in their mutual, vital, lifelong passion, the crazy project of running their own theatre company, remaining tied in a bond that was more-than-a-marriage for the rest of their lives.

Nevertheless, in late middle-age, all of a sudden Molière did marry. And this marriage was to someone young enough to be his daughter, the stage-struck seventeen-year-old Armande Béjart. Who – according to elaborately falsified birth certificates no one seems to have really believed for one moment – was Madeleine’s little sister.

This Armande, nicknamed Menou, was in fact Madeleine’s daughter, and all the world knew it. Gossip had it her father was one Esprit de Raimond de Mormoiron, Comte de Modène, a nobleman with whom Madeleine most certainly had an affair, and a son.

Was he Menou’s father? We’ll never know.

While Molière was in favour with the Court, the falsified birth certificates sufficed. If the King said so, then all the world accepted the truth that Menou was Madeleine’s (albeit unlikely) sister. But the distribution of favour, power and patronage is fickle and arbitrary – no one knew that better than Molière (and Bulgakov?). Once Molière had cultivated some enemies – he had lots of enemies, you could not be so popular or audacious a writer as he and not have enemies – then, just waiting, ready to be viciously, maliciously, used against him by those out to ruin him, were these rumours, accusations of having broken the biggest taboo, and having committed the worst crime, incest.

Let’s rewind to Molière’s beginnings. Poor old Monsieur Poquelin! Upholsterer by Royal Appointment to Louis XIV of France, his twenty-year-old son, Jean-Baptiste, was a great disappointment to him. He’d shown no interest whatsoever in the family trade; indeed, since his early teens had wasted all his time and his father’s money in pursuit of the rough and magical theatre life of the Pont Neuf among the shysters and the snake-oil salesmen and the mountebanks and the players.

Then, after an expensive education at the University of Orléans his father had paid through the nose for, just when the boy was finally coming out for a lawyer, did he not – what a cliché – have to fall for an actress? Worse still, beautiful, red-haired and four years his senior, this Madeleine Béjart has persuaded the daft lad to set up a two-sous theatre company with a handful of her rackety relatives from her tribe of troupers – real pros, the Béjart clan, a talented if ragbag theatrical dynasty. Young Poquelin ran away with this circus and, just as his father feared, never looked back. Even added insult to injury and changed his name to Jean-Baptiste Poquelin de Molière.

Dad Poquelin was just furious. He didn’t realise this ‘Molière’, was destined to become one of the world’s very greatest comic playwrights, the comedy-drama of his own life ending with him – while playing the lead role in his new play Le Malade Imaginaire, aka The Hypochondriac — being taken mortally ill and collapsing on stage (whilst, taking it for merely a hilarious part of the action, the audience laughed and laughed as Molière was dying). He was buried in unconsecrated ground, as befitted a disreputable member of a degenerate profession.

If the twenty-year-old Jean-Baptiste Poquelin hadn’t been so smitten by Madeleine, might he have made a brilliant advocate, with his gift for articulating an argument to its baroque conclusion and beyond? No, seems he was stuck from the start with the dramatist’s imperative – to put both sides of it.

As a wee boy, Jean-Baptiste had discovered that not only did he have an acute talent for mimicking his mother’s priest, but also what a most satisfactory hullabaloo this caused, with his father involuntarily in stitches and even his devout mother deliciously torn between hilarity and disapproval.

It was all laid out in front of him from that moment on. His harlequin-chequered life of ironies, of ups and downs, successes and failures, of Paris and the provinces, of plaudits and penury, of patronage lavished and patronage brutally and arbitrarily withdrawn; works written, rewritten, works alternately fêted and banned, fought for, forbidden again – like his masterpiece Tartuffe, so despised and rejected before suddenly, out of the blue, the ban being revoked and it being given a swish production ordered by the King – his private life lived all-too-publicly, that life of forbidden love, of purple scandals and painful cuckoldings, that life of accusations. Blasphemy! Incest!

I constantly marvel at Molière’s – what, bravery? blindness? emotionally opportunistic cold-eyed pragmaticism? – because, while suffering genuinely and terribly over young Menou’s infidelities – she was apparently pathologically unfaithful and the model for the delicious, wicked, faithless Célimène in The Misanthrope – he was also able, in School for Wives, to ridicule old Arnolphe’s foolish passion for a girl far, far, too young for him and who loved him not a jot – as neither she should. I am boggled by how real personal anguish was regularly turned into absolute hilarity for others to laugh at.

Molière and Madeleine’s company were initially influenced by the Italian Players. The great Scaramouche taught him all he knew, and something of the folk art of the commedia dell’arte and its stock comic masks remains within his all-too-human and real unique eccentrics. Every one of his characters is at once a perfect type and also a unique and absolutely live-and-kicking human being suffused with that particular individual’s peculiar mania. Each is a slave to some obsession which, pursued to the nth degree as it damn well always is, only serves to bring about the thing each protagonist most deeply fears.

All the comic energy, all the sympathy, is always with this mad protagonist. There is always in a Molière play an honnête homme, a character advocating, often comically ad infinitum, simple common sense. Which never does prevail. When, often via a ‘deus ex machina’, a happy ending out of nowhere, we get that sudden reversal to the ideal order of things, it is always quite ironically, even cynically, deadpanned as not bloody likely.

A lack of any sense of proportion whatsoever mars the psyche of all of his protagonists, yet there’s a complexity and mystery at the heart of each compulsion. Why does Orgon need to believe in the conman Tartuffe? Why would a slave to the truth, an absolute anti-liar like Alceste in The Misanthrope, fall in love with Célimène and her cheating ways? What on earth makes old-man Arnolphe in School for Wives, in the face of all the evidence constantly confirming Agnes’s deep and passionate love for her proper young man Horace, believe he can actually bully her into loving him?

We do not know why these things are so, but, hey, life is like that. Molière is one of the very greatest comic playwrights the world has ever known. One ‘whose plays are universal in their application yet untranslatable’, according to a snooty contributor to The Oxford Companion to the Theatre, deploring the fact that, ‘In translation the wit evaporates and only a skeleton plot is left. This, however, will not deter people from trying.’

Scots playwrights more than most, have long been guilty of this supposedly foolhardy exercise. Had I known about Scotland’s Molière tradition at the time – or indeed anything about Molière – would I have felt inhibited when, well over thirty years ago now and out of the blue, I got the phone call and the offer – and innocently embarked on my version of Tartuffe for Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum?

Probably not. Since then I’ve begged and lobbied to do the other great Molière rhyming masterpieces. See, it’s the fun of the rhyming that I can’t resist, even if it all does tend to get a bit more Ogden Nash than deathless alexandrines. Anyhow I’ve cemented my lifelong passion for Molière by rendering Le Misanthrope as Miseryguts in 2001 for the same theatre. Also – for Theatre Babel in 2006, the Lyceum in 2011 – Educating Agnes from L’École des Femmes. Now I’ve written a play about the man himself. And he speaks in, what else, Scots. Prose though. The rhyming fragments of the plays you see them working on in this play that are meant to show and celebrate the hard work of making theatre, are all from my rude and rough versions.

Why has there been so much MacMolière though? Is it because we have no plays of our own from this time? Are we filling a gap? Our Reformation, early and thorough, stamped out all drama and dramatic writing for centuries. Our indigenous cache seems to consist almost entirely of Lyndsay’s 1540 Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis – and one satire is definitely not enough. There are no Scottish Jacobean tragedies, no Scottish Restoration comedies. Our greatest dramatist-that-never-was, Robert Burns, lacking a theatre or stage to work on, confined himself to the dramatic monologue purely in poetic form. Holy Willie and Tartuffe, fellow archetypes in lust and hypocrisy, could be brothers, though.

What is there about this particular seventeenth-century Frenchman that has made him our darling here in Scotland? Well, for one thing, he’s a lot funnier than Corneille or Racine, and our best Scottish theatre actors have tended to be comedians.

The cover of Noël Peacock’s excellent Molière in Scotland features a photograph of our great Duncan Macrae as Tartuffe. He’s fingering the décolettage of Elmire with a ridiculous and naked expression of foolish lust on his skinny, long-mouthed, long-nebbed face and in his glittering eye. Back in the eighties I saw Robert Kemp’s Let Wives Tak Tent, that lovely evergreen Scots version of School for Wives, starring a hideously and hilariously predatory Rikki Fulton as that poor old man, Arnolphe, so painfully in love with the young girl.

If in all this there is a whiff of a certain vigorous vulgarity, a music-hall broadness in the playing, surely this is better than the stilted and mannered orthodoxies of the Comédie-Française? Here in Écosse Molière is funny.

Thon Man Molière: or Whit Got Him Intae Aw That Bother is a fictional, imaginary work about Molière. And Madeleine. And their wild, great illustrious theatre company – not a sensible honnête homme among them.

As I’ve said, no it doesn’t rhyme. Yes, it is in Scots, sort of, though I defy any speaker of English not to understand every word of it. (It could be adapted to any other strong idiom.) It had a brilliant first production at – where else? – the Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh, with a joyous ensemble led by the truly extraordinary Jimmy Chisholm and Siobhan Redmond as Molière and Madeleine. It was directed by my long-time Molière-collaborator (sometimes actor, sometimes director, always as mad-about-the-man as I), Tony Cownie. Thanks to Neil Murray, the designer I always love to know will be working on anything of mine, it looked fantastic, just perfect. I haven’t enjoyed working on anything so much in decades. Nor been so pleased with the result. It was, in the end, neither hard or easy – just a whole year’s obsession. Dying to see it in print now, dying for it to have another production, please.

The Bulgakov biog – now a bit battered and dog-eared by being carried about with me everywhere I went for over a year, and being my bible, constantly consulted and referenced – is back up on my bookshelves. This new Nick Hern book and the play it contains is dedicated with love to my friend Helen Simpson, who knew better than I that I needed to write it.

For Helen Simpson

Characters

MOLIÈRE, a playwright, and a player

MADELEINE BÉJART, his leading actress

‘MENOU’, aka the Wean, her sixteen-year-old daughter, Armande Béjart

GROS-RENÉ DU PARC, a leading actor of a recognisably camp and fruity type

THÉRÈSE DU PARC, his wife, a self-obsessed actress

MICHEL BARON, an actor, juvenile lead. Handsome. Physically dexterous.

TOINETTE, the company’s maid, Jill-of-all-trades. Pathologically truthful.

There is a fluid, no-fixed-location set, minimal props, but exquisite, really good period costumes.