4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

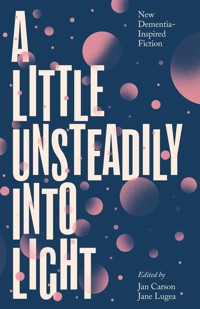

New fiction by: Suad Aldarra Caleb Azumah Nelson Jan Carson Elaine Feeney Oona Frawley Sinéad Gleeson Anna Jean Hughes Caleb Klaces Naomi Krüger Henrietta McKervey Paul McVeigh Mary Morrissy Nuala O'Connor Chris Wright To live with dementia is to develop extraordinary and various new ways of being – linguistically, cognitively and practically. The storyteller operates similarly, using words and ideas creatively to reveal a slightly different perspective of the world. In this anthology of fourteen new short stories, commissioned by Jan Carson and Jane Lugea, some of the best contemporary writers from Ireland and the UK powerfully and poignantly explore the depths and breadth of the real dementia experience, traversing age, ethnicity, class and gender, sex and consent. Each writer's story is drawn from their own personal experience of dementia and told with outrageous and dark humour, empathy and startling insight. Here are heroes and villains, tricksters and saints, mothers, fathers, lovers, friends, characters whose past has overshadowed their present and characters who are making a huge impact on the world they currently find themselves in. They might have dementia, but dementia is only a small part of who they are. They will challenge, frustrate, inspire and humble you. Above all, these brilliant pieces of short fiction disrupt the perceived notions of what dementia is and, in their diversity, honesty and authenticity begin to normalise an illness that affects so many and break down the stigma endured by those living with it every day. Find out more about the AHRC-funded research project based at Queen's University Belfast, from which this anthology has emerged: www.blogs.qub.ac.uk/dementiafiction/

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

A LITTLE UNSTEADILY INTO LIGHT

First published in 2022 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Compilation and Introduction © Jan Carson, 2022

Compilation and Afterword © Jane Lugea, 2022

Individual stories © Respective authors, 2022

The rights of Jan Carson and Jane Lugea to be identified as the editors of this work have been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-84840-861-6

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84840-862-3

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

The epigraph is quoted from Erwin Mortier’s Stammered Songbook: A Mother’s Book of Hours, translated from the Dutch by Paul Vincent (2015) and is reproduced by kind permission of Pushkin Press.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Set in 11.5 on 14.2 pt Adobe Caslon Pro

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland

Contents

Introduction

Jan Carson

This Small Giddy life

Nuala O’Connor

Downbeat

Chris Wright

People Who Want History Want History

Naomi Krüger

The Three Strangers

Suad Aldarra

A New Day, Tomorrow

Henrietta McKervey

What, You Egg

Elaine Feeney

Our Dear Ladies Have Outnumbered Us

Jan Carson

Heatwave

Oona Frawley

The Portal

Caleb Klaces

Fingerpost

Mary Morrissy

Immurement

Sinéad Gleeson

Sound Distraction

Anna Jean Hughes

Coming and Going

Paul McVeigh

My Way Home

Caleb Azumah Nelson

Afterword

Jane Lugea

Acknowledgements

Contributors’ Biographies

A human being is difficult poetry, which you must be able to listen to without always demanding clarification.

— Erwin Mortier

Introduction

Jan Carson

I was in my early twenties when my nana was diagnosed with dementia. She was the grandparent I was closest to. It wasn’t just time spent together. In a family bent towards engineering and mathematics, Nana was my only fellow creative. She knitted the most incredible sweaters, making patterns up in her head. She sang and baked and played piano. She was deeply invested in the local community. Nana was the sort of person who didn’t need to seek out stories. Stories seemed to cleave to her. As a fledgling writer I felt deeply at ease in her presence, chatting as we tootled about in her Mini Metro, or reading on her sofa while she played piano in the dining room.

It took almost a decade to lose my nana. At times this felt like a gradual erosion. The dementia slowly pared her back until she was barely recognisable; a much smaller woman, in every sense. There was a great deal of sadness in this journey but also moments of clarity, honesty and even joy. We laughed a lot. I had not anticipated laughter. However, subsequent experiences with dementia have taught me that humour can often be found in the odd situations it pitches you into. Dementia – much like life itself – isn’t simple or easily defined. It’s a muddle of competing emotions: the good, the bad and the ugly, often experienced simultaneously.

When Nana moved from her home to a residential care facility, she lost access to her beloved piano for the first time in seventy years of daily playing. The deprivation hit her hard. I could empathise. I knew I’d desperately miss reading and writing if these comforting practices were suddenly snatched away from me. It seemed like an unnecessary cruelty. Even now, nearly fifteen years into facilitating arts activities with older people, I still think about Nana and her absent piano each time I begin a new project. Every workshop is a fresh reminder that creativity and personal expression are part of what make us human. Everyone, including those living with dementia, has the right to access these experiences. Nana was my first significant encounter with dementia. I’ve had dozens, if not hundreds, since. Each has shaped me as both a writer and a human being. I’ve been challenged, frustrated, inspired and frequently humbled by the people I’ve met along the way.

There’s a strong chance that you’ve been similarly impacted by dementia if you’ve chosen to pick up this book. I’m conscious that these stories may bring to mind a friend or family member who has dementia, or who you have lost to dementia. You may be living with dementia yourself. These stories will resonate on different levels depending upon your experience of the disease. There’s no right or wrong reaction. We writers are just grateful for your consideration and time. Dementia is an umbrella term. It covers a wide range of diseases and conditions linked to memory impairment, difficulties with cognition and social ability. Each person living with a dementia will experience a unique set of symptoms and circumstances. No two dementia experiences are the same. Each fictional account of dementia in this book is equally unique. As you read the stories collected together in this anthology you may recognise situations and symptoms you’re familiar with. You may also encounter a version of dementia radically different from the one you’ve experienced yourself. As the editor, I’ve actively sought out stories which explore a wide and eclectic range of dementia experiences. I wanted to reflect the full story of how dementia is impacting society.

It’s almost impossible to estimate the true extent of dementia, however the Alzheimer’s Society estimates that about 900,000 people in the UK have dementia at present. They expect this to rise to over 1 million by 2025. Whether you’re a carer or family member, a neighbour, work colleague or friend, or you’re living with dementia yourself, it’s likely that the illness has already touched you or may soon become a significant part of your life. There are many reasons why dementia seems to be on the increase. A rise in life expectancy, better diagnosis rates and ongoing work to dispel stigma are all contributing factors. Dementia is not a new illness but society is slowly becoming more dementia aware. Organisations like Dementia NI and the Alzheimer’s Society, which offer support and carry out vital research, have been active in promoting informed and positive messages about dementia. As a result, people living with dementia are much more empowered, vocal and visible than in the past. Though much work is still to be done in Ireland and the UK, and there are still some countries where people living with dementia are routinely hidden away or institutionalised, the practice of shaming or ignoring those living with dementia is thankfully on the decline.

These days, dementia is a topical subject, not least in the arts. Almost all the TV soaps have now included major storylines exploring dementia. Recent films like Still Alice and The Father have also tackled the subject, often to great critical acclaim. A contemporary explosion of memoir and non-fiction books shows there’s not just an interest but also a market for writing which explores the reality of a dementia diagnosis. I’d thoroughly recommend reading some of these books. I’ve been particularly impressed with non-fiction works in translation by writers like Annie Ernaux, Arno Geiger and Erwin Mortier, who has kindly given us the beautiful epigraph for this collection.

My own particular world is prose fiction – the reading, writing and dissecting of stories – and it’s fair to say there’s been a similar boom in dementia fiction over the last twenty years. In the last decade, all the major fiction prize lists have included novels like Avni Doshi’s Burnt Sugar and Emma Healey’s Elizabeth is Missing which explore the dementia experience. Pre-millennial prose writers occasionally included a character living with a dementia-like illness. Rarely was the condition named as such and, with a few notable exceptions, there were almost no novels entirely focused on dementia. Post-millennial writers appear much keener to consciously explore dementia in their fiction. This trend, though not without its problems, seems ripe for celebration and further study. It’s heartening to see a growing number of academics around the world currently researching how dementia is depicted in contemporary writing, and constantly adding to the body of robust critical work on this important subject. Many of these academics have contributed to the collation of this anthology and I’m extremely grateful for their help.

I am not an academic. I’m a writer and arts practitioner. However, I jumped at the chance to join the ranks of academia for a couple of years. In early 2020, as the world geared up for a global pandemic, a small team of academics from Queen’s University, Belfast began a research project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, working with carers, trainee social workers, readers and people living with dementia to investigate how dementia is depicted in the words and thoughts of characters from contemporary novels. As a practising writer I was invited to join this project. My role was to ensure our research had a meaningful impact on the wider community. I took part in reading groups, discussing our ten key texts. I facilitated workshops for emerging writers who wished to wrestle with the ethics and practicalities of writing about dementia. I helped to run a first-of-its-kind symposium, bringing together academics, writers, support organisations and, most importantly, people living with dementia. We shared stories, frustrations and ideas. We discussed how to write well about dementia. It felt like the beginning of an incredibly significant conversation. I learnt an enormous amount in two short days.

Over the course of the project, I also read approximately one hundred fictional accounts of dementia. I read novels, stories and plays from across the world. I read books for children and young adults, crime fiction, magical realism, graphic novels, science fiction, literary fiction, romance and just about every other genre in existence. Some of the writing was truly brilliant and included deftly drawn characters whose dementia served to make them more believable and interesting. Some of the books I read were dire. They recycled tired tropes and lazy clichés. Some writers appeared to have done absolutely no research and as a result had written books which were at best factually inaccurate and at worst, downright dangerous. While it was encouraging to see more writers engaging with dementia, it was abundantly clear there was still room for improvement. I soon realised there was a distinct lack of diversity in the dementia novels and short stories which have so far emerged. This anthology of newly commissioned short stories is a small attempt to redress the existing balance of dementia fiction. The fourteen established and emerging writers included here have personal experience of the illness. They’ve brought their own diverse backgrounds to their writing. They’ve spent time in workshops discussing the ethics and practicalities of writing dementia. They’ve carried out significant research. In short, they’ve done their best to faithfully capture a lived experience which, though close, remains outside themselves. I believe that dementia offers the fiction writer a rare opportunity: a chance to think imaginatively and ethically about how we tell an other’s story.

The question of appropriation currently looms large over literature. Who owns a story? Can a story be owned? Is it wrong to write about something you have no lived experience of? In the past, when a writer’s creative integrity was questioned, they could simply cite the notion that fiction was ‘just making stuff up’ and from this, somewhat wobbly, platform continue to write from the perspective of whatever ethnicity, gender, class or sexual identity took their fancy, inventing experiences they were ignorant of. Thankfully most contemporary writers are much more aware of the harm and hurt which can be caused by the wilful or crass appropriation of someone else’s story. However, there are still those occasions when writers find themselves drawn to another’s stories which, for myriad reasons, have yet to be told, or moments when they’ll wish to populate a novel with characters which aren’t simply identikit versions of themselves. On such occasions an empathetic, ethical and creative understanding of how to write the unlived experience could provide a framework for avoiding the pitfalls commonly associated with appropriation.

There is a growing number of writers living with dementia who’ve written their own memoirs or collaborated to write in partnership. I’d recommend Wendy Mitchell’s incredible books, written in partnership with Anna Wharton, and the work of Living Words UK who run bespoke writing projects for people with dementia. However, many people living with dementia will struggle to create a comprehensive and coherent narrative of their experience, particularly during the later stages of the illness. In compiling this anthology we’ve done our best to help the fiction writers we’ve included balance careful research with deep respect as they write about lives they have not lived, and experiences they’ve only been party to. A certain degree of careful appropriation is deemed necessary here, for if writers aren’t willing to imagine the lived experience of dementia, many of these stories will never be told. The implications could be catastrophic. There’s already a great deal of ignorance and fear surrounding dementia. Fear can keep people from seeking an early diagnosis and consequently rob them of the help and treatments available. The more dementia is represented diversely and honestly in the arts and media, the more the illness will be normalised and the less stigma those living with it will have to endure.

And yet, the writer’s primary job is not to educate. The writers selected for this anthology had no remit to produce helpful, educational information, designed to help the reader better understand dementia. Fiction writers are first and foremost storytellers, lovers of language and makers of art. The commitment to telling a really good story has to override every other pressing agenda. All a writer of fiction is required to do is captivate and suspend disbelief. The fourteen pieces included in the anthology are, above all else, brilliant stories. They just happen to touch upon different aspects of dementia. They aren’t bound by the need to put a positive or educational spin on the subject. A writer walks a fine line when fictionalising any big issue, be it dementia, the climate crisis or the latest scandal in Hollywood. The narrative is in constant tension with the desire to inform and interrogate. The writer’s a bit like a lion tamer, holding the issue at bay in the corner so it isn’t allowed to overwhelm the story, rendering it overly didactic, which is to say, a terrible read.

I’ve learnt the hard way that the trick to approaching a real-life issue like dementia from a fictional slant is to invest in great characters. Characters who are charged with depth and nuance. Characters who feel so real, the writer can simply take a back seat, allowing them to tell their own story in their own voice. If a character is simply a poorly developed mechanism for advancing the plot, the story itself will lack appeal and believability. In my reading research, I came across several examples of paint-by-numbers stock characters whose dementia felt like a rather obvious vehicle for adding an extra layer of confusion within a crime fiction plot or messing around with time and alternative realities in science fiction and magical realism. This isn’t just bad dementia fiction. It’s bad fiction full stop. Most great stories begin and end with interesting, complex and well-developed characters.

In this collection you’ll meet intriguing characters you’ll want to spend time with. You’ll feel sympathetic and occasionally maddened and keen to discover more about their lives. You’ll let these characters lead you into strange and sometimes difficult places because they are infinitely believable. If you’re not careful, you might even forget for a moment that they and their stories are not real. Much has been written about the importance of fostering empathy in order to understand conditions like dementia. Extensive reading has taught me that an emphasis on character is perhaps the most essential facet of great dementia fiction. While an infographic or magazine ad can impart information, there’s nothing like losing yourself in a character’s world to begin the process of appreciating what a lived experience of dementia might feel like.

There is an increasing awareness of the need to offer people living with dementia support and community, often through peer-led groups. However, Wendy Mitchell, the writer and dementia activist, writes in her brilliant book, What I Wish People Knew About Dementia, ‘In an ideal world, there wouldn’t be any need for these niche groups. We only really have peer support groups because society won’t make the adjustments that would allow us to integrate.’ Much work still needs to be done but programmes like the Alzheimer’s Society’s fantastic dementia-friendly training scheme and other local and national-level projects have sought to make it easier for people living with dementia to integrate into our communities in a natural, inclusive way. If widespread understanding of dementia increases and prevailing stigmas continue to be challenged, there’s no reason why the future won’t see a decrease in specialised dementia-focused groups and a bent towards more comprehensive integration where existing services and activities become welcoming, inclusive environments so people with dementia can participate and contribute alongside their neighbours and peers.

In my reading, I began to notice a similar trend within dementia narratives. Many of the novels which I read were not primarily focused upon dementia, yet included peripheral characters and incidental plotlines where dementia was a theme. It’s heartening to see contemporary writers beginning to rethink what a snapshot of diverse community could look like within the context of a novel. As society begins to develop a more inclusive attitude to dementia, people with dementia will become even more visible. In the same way that it’s becoming much less common to see fictional portrayals of a society which doesn’t include disability, ethnicity, gender, class and sexual diversity, the incidental depiction of dementia should hopefully become a common occurrence on stage, page and screen.

Similarly, we can hope to see a wider range of characters living with dementia. Anyone can develop dementia. It’s not just an old person’s illness. It pays no heed to class, gender or ethnicity. Nice people develop dementia. Horrible people can get it too. Consequently fictional characters with dementia should also be diverse. They should exhibit every kind of human trait and emotion, be party to every kind of experience – including the intellectual and sexual – and evoke a huge range of responses from the reader. In short, every character with dementia should be unique and distinct. It seems almost redundant to say this, but I feel compelled to. I’ve read over a hundred dementia narratives yet I’ve come across very little nuanced understanding of diversity within the dementia experience.

The typical character who’s living with dementia in contemporary literature is white, middle/upper class and invariably a woman; usually of the doddery but sweet variety. These characters almost always evoke feelings of sympathy and occasionally pity. It’s easy to feel sympathetic towards these stereotypical characters because, aside from the odd feisty or humorous outburst, they’re pretty nice people. Picture a kindly, cardiganed grandma who occasionally muddles up her words. Nine times out of ten we encounter these characters in a residential care facility. Most have the ability to self-finance their care, though they’ll inevitably have a partner, child or concerned friend anxious to ensure their loved one is well looked after as they approach the end of life. I’m not going to name and shame any fellow writers but there are a huge number of these lazy depictions of dementia circulating round our bookstores and libraries.

I find these portrayals quite frustrating. I’ve spent more than fifteen years working in older people’s arts engagement. I’ve frequently encountered incredibly diverse experiences of dementia and an ongoing struggle to access affordable care. It’s not to say the kindly grandma with dementia doesn’t exist – my nana was a case in point – but the bigger picture of dementia is a much more diverse and complex one. Furthermore, I’ve come to resent the way the vast majority of characters living with dementia are written to elicit sympathy. They’re almost always the victims in a story. They are passive, reduced and frequently written with the implicit understanding that their worth is tied up in their past. Now, I’ve met some lovely people with dementia and it was really easy to spend time with them. I’ve also worked with irritating, demanding and downright obnoxious people who have dementia. Sometimes these traits are symptoms of their diagnosis. Sometimes they were just difficult people who happened to develop dementia. It feels reductive, and possibly even discriminatory, to suggest a person living with dementia has to fit into a stereotype. It goes against everything I know about how complex human beings are and, though it should not require saying, people living with dementia are human beings too.

In this anthology you’ll find heroes and villains, tricksters and saints, mothers, fathers, lovers, friends, people whose past has overshadowed their present and people who are making a huge impact on the world they currently find themselves in. Each one is unique. Each one is a complex mix of emotion and experience. These characters might have dementia, but dementia’s only a small part of who they are. You may recognise some of these people and the way they behave from your own experience of dementia. Other characters may be unfamiliar or even a little unsettling. You might find yourself wondering what’s going on and whether the writer in question has misrepresented the dementia experience. As you read, please bear in mind that every dementia is unique. Dementia is not limited to elderly people. Dementia isn’t just forgetting or misplacing words. A dementia diagnosis can impact a person’s moods and emotion, spatial awareness, physicality, senses, relationship and personality. Dementia can affect every aspect of life. I’ve tried to include stories which question perceived notions of what dementia is.

Most writers, myself included, relish the opportunity to be challenged by our work. We like to learn and develop as artists through the process of creating something new. The writers commissioned to produce new stories for this anthology have talked about how stimulating and inspiring they found the project. Unlike many regular writing commissions, this project included plenty of room for research and discussion in the development process. Our team facilitated workshops focused on how language could be used experimentally and creatively to capture something of the dementia experience. We shared reading recommendations, hosted discussions, and made our research findings available to all the writers involved. The thirteen writers included here along with myself developed these stories, mindful of the constraints associated with writing dementia. It was an absolute joy to see how they rose to this challenge. They’ve all worked extremely hard to achieve authenticity in how they’ve portrayed the thought life and dialogue of characters living with dementia. I suspect that they’ve been shaped by the process, on both an artistic and human level. Whether you’re reading or writing it, an encounter with a good story almost always leaves you a little changed.

My own writing practice has been changed by my experiences with dementia. I’ve become intrigued by the various patterns, tics and language constraints associated with the illness. Early on, I began to see the creative possibility in telling a truth a little slant or finding a more roundabout, poetic way of conveying a misplaced or muddled sentiment. I’ve spent a lot of time listening to the people I work with and revelling in the way they use words in striking and unusual ways. In my own writing, I’ve played around with the linguistic possibilities presented by repetition, under-lexicalisation and malapropisms, (all common language issues associated with dementia). I’ve also noticed and utilised other frequently recurring aspects of the dementia experience, such as changes in sensory awareness, confusion and a more fluid awareness of time and space. Rather than finding these constraints restrictive, I’ve felt temporarily liberated from the limitations of traditional literary language and form. It’s felt like being given licence to experiment and play. This is a sentiment echoed by many of the writers who’ve contributed here. You’ll see, in these stories, just how much they’ve enjoyed exploring the potential of the dementia narrative. They’re grateful for the opportunity to see the world from a slightly different perspective and discover new ways to story their words.

And yet, dementia remains a slippery subject to pin down in words. The experience of living with dementia is so varied and personal it cannot be captured definitively on the page. In researching and developing this anthology we’ve constantly walked a very fine line, balancing an honest representation of an illness which can be extremely cruel and devastating and for which there’s currently no cure, with the lived experience of the people we know who are living hopefully, tenaciously and as well as they can with dementia. It would be a disservice to these people to paint a picture of dementia which is entirely negative and yet, as writers, we must also strive for realism, honestly capturing the moments when dementia makes life feel unbearable.

Consequently, I’ve chosen a quote from Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape as the title for this anthology. In my reading, I came across few examples of writing which better explore the dementia experience than this short play. Beckett manages to authentically capture the humour, pathos, profundity and confusion of trying to hold onto an understanding of yourself as memory erodes and language unravels. It’s a short, but devastatingly powerful play which includes the stage direction, ‘a little unsteadily into light’. I found this a helpful and accurate summary of our attempts to strike that fragile balance when writing authentically about dementia. I think these words also say something powerful about living as well as possible with dementia. Arguably, they speak to us all. For aren’t most human beings simply doing their best to move a little unsteadily into light?

This Small Giddy Life

Nuala O’Connor

‘Is that plastic?’ Imy taps a fingernail against the urn. ‘Trust Mam to end up in a shitty pot.’

‘It’s brass. Painted.’ I frown and rub my hand over the cold surface. ‘That’s what I ordered, anyway.’

The urn sits on my kitchen counter, the lid wedged shut; I take a knife from the block and prise it open. We peer in at the ashes.

‘Wormy poo,’ Imy says. ‘Bird plop.’

‘Cremains,’ I say, and we both laugh, the same stupid, in-unison snorts we’ve done all our lives. I close the urn and it sits there, horribly present and, somehow, vital.

‘What’ll we do with her?’ Imy asks.

‘Same thing we always did with Mam, I suppose. Put up with her.’ I sigh and push away tears with my fist. ‘The last thing she got from me was blame, Imy.’

My sister shrugs. ‘It doesn’t matter, Sharon; she was beyond understanding, you said it yourself.’ She pokes at the urn with the knife until I take it from her. ‘What sort of blaming was it?’ she asks.

I flick my hands through my hair and stare at the table instead of Imy. ‘I said, “I’ve no clue how to fit into my own life, and it’s your fucking fault, Mam.” Do you think she heard? Understood?’

‘She was hopped up on morphine, didn’t even know where she was. Or who she was.’

I sigh. ‘Well, none of us knew that.’

*

We move to a place where backstory is not allowed; over and again we move to this place. People are coldly civil towards my mother; she draws that out of them. Men like her well enough, but women are often hostile. Mam makes no pretence at being widowed, or still married to whomever, and she gets disapproval in return for her honesty, her lack of cover-up. God knows she hides everything else, but no one likes a woman alone in these places, especially one with two daughters. A handsome woman who might do harm to husbands; a woman who talks a lot, who asks questions, and reveals herself too soon. A woman with obvious appetites.

We move constantly because Mam is hunting down some elsewhere that will fit her and not one of these places is ever right. Up and down Ireland we drive, back and across: she needs to be near the sea; she needs the bustle of a town; she needs a friendly village; she needs the thrum of a big city; she needs a huge old house in the middle of a field, with only sheep for company. Nowhere works.

‘There’s something awful mean-spirited about Galway,’ Mam says, after five months in Connemara.

Sligo is unmercifully wet.

Dublin frenetic and grey.

Villages are too native and small towns have no get-up-and-go.

On we travel.

In each new place, in the early days of our arrival, we sit in pubs while Mam cajoles information from landlords and locals.

‘Would there be a little job going in here, by any chance?’ she’ll say, offering a lipsticked grin.

The barmen lean down, all silly smirks and bonhomie. ‘Well, there just might be for a lassie like yourself. What’s this you said your name was?’

‘Margaret.’ Wreaths of smiles. ‘But my friends call me Meg.’

Mam asks barmen, too, about flats and houses, always determined to find something better than whatever shithole we’ve landed in ‘for the time being’. But the time being is the only time our mother knows; there is no past, there is no planned-for future, those are inconveniences. In pub lounges all over the island, my sister and I sit at low tables, drinking cordial from glasses Laliqued with Tayto grease, while Mam perches at the bar, preens and flirt-chatters, and sips on a small stout, sweetened with blackcurrant.

Here we are in Ummoon, County Mayo. There we are in Portarlington, County Laois. Now we meet ourselves at the crossroads at Maam, blowing away from Clifden town as fast as we blew in. Meg driving and singing ‘She’ll be comin’ ’round the mountain when she comes’, or gripping the steering wheel in grim silence, which is worse. We don’t know where we’re from, Imy and I, or where we’ll end up, and we don’t dare ask our mother.

*

‘You can get necklaces made with the cremains, you know,’ I tell Imy. ‘There’s a website. They put the ashes into glass pendants. It looks like swirly sand.’ I swizzle my finger in a circle.

Imy snorts. ‘You want me to have Mam permanently around my neck? No fucking thanks, Sharon. Jesus, the things you come up with.’

‘What? I thought it’d be nice. A bit of Meg to take back to Spain with you.’

‘Nice! But why would you want to bother? The woman drove you mad.’

I frown. ‘Not always, Imy. Her illness changed her; she wasn’t as spiky as before.’ I feel let down. ‘And she was still our mother.’

*

I first notice a waywardness in Mam when she’s turning sixty; she seems more harum-scarum than ever, yet more contained too. It’s just small forgettings at first, and muddles about objects, about where exactly she lives.

She’ll ask, ‘Where’s this I am now?’

‘Galway,’ I say. ‘Rahoon. Remember? This is your flat.’

‘Galway? Oh!’ she replies, as if it’s a curiosity to her.

She forgets, too, to keep her place clean, and she no longer asks anything about me: my daily doings, my job, my love life. These lapses begin to link together until I see something definite in her: a solid absence. It’s as if she operates as two people: the reasonably together woman who knows me and acts like Mam, and the vague, incurious woman who appears when knowledge and truth are needed.

There’s no sixtieth party planned for her – we’ve never gone in for celebrations – but Mam rings me the day before her birthday and demands that I come immediately to Rahoon, and I can tell she’s agitated because she’s lisping slightly and snapping out her words.

I grip my phone. ‘What’s wrong, Mam?’

‘Just come over here, Sharon,’ she barks, ‘can’t you do that for me?’

Life-things have kept me away from Mam’s for a week and, when I let myself in, I’m stormed by a fruit-meat stink. Mam, though unruly in herself, has always preferred cleanliness. The bowl on the kitchen table – islanded in a sea of breadcrumbs – is packed with mildew-bloomy mandarins, and the draining board holds three opened tins of Whiskas, though my mother doesn’t own a cat.

‘The smell in here, Mam! Let me tidy up.’ I tip the oranges into the bin.

She stalks up to me. ‘That bitch at the bank won’t let me have my money.’ She’s plucking at her hair with her fingers – a recent tic – her whole face rucked to a frown. ‘I wanted a couple of grand for the party and that bitch says I can’t have it. My own bloody money!’

I pull her hands gently away from her hair. ‘What party, Mam?’

‘My sixtieth, Sharon! For fuck’s sake, what’s wrong with you?’

‘Oh. You never said you wanted a shindig. That’s news to me.’

She squints at me as if I’m the worst kind of fool. ‘It’s all arranged.’

‘But, Mam, you hate arranging things.’

‘I do not. I booked the function room at the Spinnaker; I ordered a cake from O’Connor’s,’ she says.

‘How?’

‘I rang them.’ Mam pauses. ‘I went around there. To them. I walked to the bakery.’ Her look to me is timid now, eye-slidey. ‘And to the Spinnaker.’

I frown. ‘And you’re saying you walked all the way down to Salthill to book a function room?’ She hardly ever leaves her flat. ‘Are you sure about all this?’

Mam stalls. ‘Imy organised it, actually,’ she says, jutting her chin. ‘I just need to pay now.’

‘OK, but Imy’s in Spain, so I don’t see how–’

She holds her fingers to her temples. ‘Stop, Sharon, stop! I need that money from the bank; you go there and talk to that wagon at the counter. The cheek of her! Everyone’s coming to this party. Your father. Everyone.’

‘My father?’

*

Mam lasts twenty-one months in Ennis, a long stint for us. The convent school accepts Imy and me, after a little histrionic wrangling with a sceptical nun.

‘I’m a widow, Sister,’ Mam says, squishing out a few tears.

The nun offers a brisk smile and nod, and we’re in. Unlike other schools, I settle at the Mercy and make a friend called Emer, a fellow outcast. We bond because I’m a fatherless blow-in, and Emer’s being raised by her grandparents, though her parents still live in the town. We walk home together after school and, in her company, I quit biting my nails to stumps, and sucking on my hair-ends. Emer means I can avoid home, avoid my mother and her tantrums.

Emer calls herself an ornithologist and, on our walks, she teaches me about bird habitats and behaviours, field-marks and feathers. We peer into bushes and treetops; we stake out fields and the riverbank.

‘Always watch well, Sharon,’ Emer instructs. ‘Does the bird’s tail fan? Does it wag?’ She pats her chest. ‘And look at the underbelly markings too. You need to be observant.’

We stalk every tree and bramble in Ennis.

‘Do you want to see my collection of feathers?’ Emer asks one day.

It’s my first invitation to another girl’s house and I feel sick with anticipation. Emer’s grandparents are not the ancients I was expecting; they don’t look much older than Mam. Emer’s already whispered to me that her mother was fourteen having her – our age – and we’ve giggled and grimaced over the idea of letting a boy put his smelly thing inside our legs.

Her granny waves to us when we flit through the kitchen, to get to Emer’s bedroom. There’s a fireplace in the room and all along the mantelpiece are empty stout bottles, stuffed with feathers. I trail my fingers over the tops.

‘Beautiful,’ I say. ‘They look like flames. Like flowers.’

‘I really want to find kingfisher feathers; they’re the prettiest of all the Irish birds. I’d love to see one – they fizz through the air.’ She dive-zooms her hand.

‘I’d love that too,’ I say.

‘Kingfishers foretell death,’ Emer tells me, and I nod solemnly, as if this is something I already know.

‘Have your tea here, Sharon. I’ll get Granny to ring your mammy.’

Tea in Emer’s house is egg sandwiches and cake, taken quietly around the kitchen table, on blue-striped plates. In our flat, it’s foraged baked beans and toast, or whatever Imy and I can put together, while Mam works. Emer’s granny and grandad butter slices of barmbrack and eat them without speaking. Nobody argues or accuses, shouts or rages, laughs or brings news, and I can barely swallow with the silence that echoes around my ears.

‘I’ll drive you home, Sharon,’ Emer’s grandad says, when we’re finished.

I sit behind him in his car, my stomach trouncing with nerves, not knowing whether to speak. Do the Boyles ever talk? Do they fight? How do they know what each other thinks?

Emer’s grandad insists on coming up to our flat above the butcher’s shop, with its linger of lard and blood in the stairwell.

‘I’m home,’ I call, and Mam comes out to the corridor.

She taps her hand across her hair. ‘Oh, Mr Boyle. Come in, come in.’

He follows her into the living-room, and I go to my bedroom, leaving the door ajar so I can spy. They talk for a minute about school, and Emer and me, then Mr Boyle steps close to Mam.

‘If you ever need anything, Meg, just ask,’ he says, ‘anything now. I know a woman alone must face hardships.’ His tongue pokes out like corned beef and he half-smiles. ‘Anything you need at all.’ He puts his hand on Mam’s shoulder, then slides it down and squeezes her breast.

Mam jumps backwards. ‘Well that I don’t need,’ she hisses.

Emer’s grandad leaps, grabs his hat, and runs for the door. Though my cheeks are blazing, I muster nonchalance and come into the living-room. ‘Is he gone?’