4,49 €

4,49 €

oder

-100%

Sammeln Sie Punkte in unserem Gutscheinprogramm und kaufen Sie E-Books und Hörbücher mit bis zu 100% Rabatt.

Mehr erfahren.

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Kim Paradowski

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

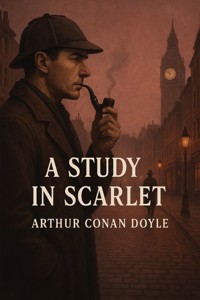

- This is an illustrated edition featuring striking artwork, a complete summary, an author biography, and a full characters list.

This visually enriched illustrated edition brings Conan Doyle’s world to life with atmospheric artwork that captures the suspense, intrigue, and Victorian setting. A clear and engaging summary helps readers follow the novel’s dual-structured narrative, while the included author biography offers insight into Conan Doyle’s life, inspirations, and the origins of Sherlock Holmes. A detailed characters list supports readers as they navigate the story’s cast, making the novel more accessible to newcomers and classic literature fans alike.

Perfect for mystery lovers, students, collectors, and anyone discovering Sherlock Holmes for the first time, this edition provides a beautifully crafted and accessible way to experience one of the most important detective novels ever written. Step into the world of Holmes and Watson and enjoy the story that sparked a global literary legacy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

0,0

Bewertungen werden von Nutzern von Legimi sowie anderen Partner-Webseiten vergeben.

Legimi prüft nicht, ob Rezensionen von Nutzern stammen, die den betreffenden Titel tatsächlich gekauft oder gelesen/gehört haben. Wir entfernen aber gefälschte Rezensionen.

Ähnliche

A Study in Scarlet

By

Arthur Conan Doyle

ABOUT DOYLE

Arthur Conan Doyle was born on May 22, 1859, in Edinburgh, Scotland, into a family of Irish descent. His childhood was marked by financial hardship and instability due to his father’s struggles, but he found comfort in reading and storytelling. He attended Jesuit schools, where he developed a strong imagination and a lifelong love of literature. These early influences helped nurture the creative spark that would later shape his career as a writer.

As a young adult, Doyle studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, where he encountered Dr. Joseph Bell, a professor known for his sharp observational skills and logical reasoning. Bell’s analytical methods made a deep impression on Doyle and later served as inspiration for Sherlock Holmes. While still a student, Doyle began writing short stories, finding early success with both fiction and nonfiction pieces published in magazines. His medical training and literary ambition developed side by side, each influencing the other.

After completing his medical studies, Doyle worked as a ship’s doctor and later opened a small medical practice in Southsea, England. Business was slow, which gave him time to focus on writing. In 1887, he published A Study in Scarlet, the first appearance of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson. The novel introduced readers to a new kind of detective fiction rooted in logic, deduction, and scientific thinking. Holmes quickly became one of literature’s most iconic characters, and Doyle’s reputation as a major writer grew rapidly.

Despite his success with detective fiction, Doyle considered himself a versatile author and wrote historical novels, science fiction, adventure tales, and essays. He also became deeply involved in public affairs, supporting various political causes and participating in legal campaigns to overturn wrongful convictions.

SUMMARY

A Study in Scarlet begins with Dr. John Watson returning to England after being wounded in the Afghan war. Seeking affordable lodging in London, he is introduced to Sherlock Holmes, an eccentric and brilliant man with extraordinary powers of deduction. The two move into rooms at 221B Baker Street. Watson is fascinated by Holmes’s unusual habits and even more amazed when he learns Holmes is a consulting detective who assists the police with cases they cannot solve.

Their first case together begins when the police discover a man named Enoch Drebber dead in an abandoned house. There are no visible wounds, yet the word “RACHE” is written in blood on the wall. The crime scene baffles the police, who cling to mistaken theories. Holmes, however, studies the smallest details—footprints, cigar ash, and the layout of the room—and determines that the death was murder, not natural causes or suicide. He also deduces characteristics of the killer long before anyone else.

When a second body is discovered—Drebber’s secretary, Stangerson—the mystery deepens. Holmes uses his keen observations and logical reasoning to track down the murderer. Ultimately, he has the culprit brought to Baker Street by posing as a cab customer. The killer, Jefferson Hope, then reveals the motive behind the crimes, shifting the story from the streets of London to the American West many years earlier.

Hope’s confession explains how Drebber and Stangerson once destroyed the lives of a young woman named Lucy and her father, who were under Hope’s protection. After Lucy was forced to marry Drebber and later died of misery and neglect, Hope swore revenge. He pursued the two men across continents for years. The murders in London were the final outcome of a deeply personal and long-standing pursuit of justice. Hope insists that he acted out of love and righteous anger, not cruelty.

CHARACTERS LIST

Sherlock Holmes

Brilliant detective known for his logical reasoning and forensic skills; solves the murders central to the story.

Dr. John H. Watson

Holmes’s friend, companion, and the narrator of the story; recently returned from military service in Afghanistan.

Inspector Lestrade

A Scotland Yard detective; often works with Holmes but is skeptical of him.

Inspector Gregson

Another Scotland Yard detective; more polite than Lestrade but still outmatched by Holmes.

Enoch Drebber

An American traveler and the first murder victim; former member of a Mormon community.

Joseph Stangerson

Drebber’s secretary and companion; becomes the second murder victim.

Jefferson Hope

The novel’s central antagonist-turned-sympathetic figure; the murderer with a tragic motive rooted in love and revenge.

Lucy Ferrier

An orphaned young woman raised by the Mormon community; central to the backstory and Jefferson Hope’s lost love.

John Ferrier

Lucy’s adoptive father; escapes across the desert with her and raises her outside traditional Mormon norms.

Brigham Young

Leader of the Mormon community; enforces strict rules that affect Lucy and Ferrier’s fate.

Mrs. Hudson (implied/mentioned)

Holmes and Watson’s landlady at 221B Baker Street (briefly referenced in the Holmes canon).

Wiggins

A street urchin from Holmes’s “Baker Street Irregulars,” who assists in gathering information.

I

MR. SHERLOCKHOLMES

In the year 1878 I took my degree of Doctor of Medicine of the University ofLondon, and proceeded to Netley to go through the course prescribed forsurgeons in the army. Having completed my studies there, I was dulyattached to the Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers as Assistant Surgeon. Theregiment was stationed in India at the time, and before I could join it, thesecond Afghan war had broken out. On landing at Bombay, I learned that mycorps had advanced through the passes, and was already deep in the enemy’scountry. I followed, however, with many other officers who were in the samesituation as myself, and succeeded in reaching Candahar in safety, where Ifound my regiment, and at once entered upon my new duties.

The campaign brought honours and promotion to many, but for me it hadnothing but misfortune and disaster. I was removed from my brigade andattached to the Berkshires, with whom I served at the fatal battle of Maiwand.

There I was struck on the shoulder by a Jezail bullet, which shattered thebone and grazed the subclavian artery. I should have fallen into the hands ofthe murderous Ghazis had it not been for the devotion and courage shown byMurray, my orderly, who threw me across a packhorse, and succeeded inbringing me safely to the British lines.

Worn with pain, and weak from the prolonged hardships which I hadundergone, I was removed, with a great train of wounded sufferers, to thebase hospital at Peshawar. Here I rallied, and had already improved so far asto be able to walk about the wards, and even to bask a little upon theverandah, when I was struck down by enteric fever, that curse of our Indianpossessions. For months my life was despaired of, and when at last I came tomyself and became convalescent, I was so weak and emaciated that a medicalboard determined that not a day should be lost in sending me back to

England. I was dispatched, accordingly, in the troopship Orontes, and landeda month later on Portsmouth jetty, with my health irretrievably ruined, butwith permission from a paternal government to spend the next nine months inattempting to improve it.

I had neither kith nor kin in England, and was therefore as free as air—oras free as an income of eleven shillings and sixpence a day will permit a manto be. Under such circumstances, I naturally gravitated to London, that greatcesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistiblydrained. There I stayed for some time at a private hotel in the Strand, leadinga comfortless, meaningless existence, and spending such money as I had,considerably more freely than I ought. So alarming did the state of myfinances become, that I soon realized that I must either leave the metropolisand rusticate somewhere in the country, or that I must make a completealteration in my style of living. Choosing the latter alternative, I began bymaking up my mind to leave the hotel, and to take up my quarters in someless pretentious and less expensive domicile.

On the very day that I had come to this conclusion, I was standing at theCriterion Bar, when someone tapped me on the shoulder, and turning round Irecognized young Stamford, who had been a dresser under me at Barts. Thesight of a friendly face in the great wilderness of London is a pleasant thingindeed to a lonely man. In old days Stamford had never been a particularcrony of mine, but now I hailed him with enthusiasm, and he, in his turn,appeared to be delighted to see me. In the exuberance of my joy, I asked himto lunch with me at the Holborn, and we started off together in a hansom.

“Whatever have you been doing with yourself, Watson?” he asked inundisguised wonder, as we rattled through the crowded London streets. “Youare as thin as a lath and as brown as a nut.”

I gave him a short sketch of my adventures, and had hardly concluded it bythe time that we reached our destination.

“Poor devil!” he said, commiseratingly, after he had listened to mymisfortunes. “What are you up to now?”

“Looking for lodgings,” I answered. “Trying to solve the problem as towhether it is possible to get comfortable rooms at a reasonable price.”

“That’s a strange thing,” remarked my companion; “you are the secondman today that has used that expression to me.”

“And who was the first?” I asked.

“A fellow who is working at the chemical laboratory up at the hospital. Hewas bemoaning himself this morning because he could not get someone to gohalves with him in some nice rooms which he had found, and which were toomuch for his purse.”

“By Jove!” I cried, “if he really wants someone to share the rooms and the

expense, I am the very man for him. I should prefer having a partner to beingalone.”

Young Stamford looked rather strangely at me over his wineglass. “Youdon’t know Sherlock Holmes yet,” he said; “perhaps you would not care forhim as a constant companion.”

“Why, what is there against him?”

“Oh, I didn’t say there was anything against him. He is a little queer in hisideas—an enthusiast in some branches of science. As far as I know he is adecent fellow enough.”

“A medical student, I suppose?” said I.

“No—I have no idea what he intends to go in for. I believe he is well upin anatomy, and he is a first-class chemist; but, as far as I know, he has nevertaken out any systematic medical classes. His studies are very desultory andeccentric, but he has amassed a lot of out-of-the-way knowledge whichwould astonish his professors.”

“Did you never ask him what he was going in for?” I asked.“No; he is not a man that it is easy to draw out, though he can be

communicative enough when the fancy seizes him.”

“I should like to meet him,” I said. “If I am to lodge with anyone, I shouldprefer a man of studious and quiet habits. I am not strong enough yet to standmuch noise or excitement. I had enough of both in Afghanistan to last me forthe remainder of my natural existence. How could I meet this friend ofyours?”

“He is sure to be at the laboratory,” returned my companion. “He eitheravoids the place for weeks, or else he works there from morning to night. Ifyou like, we shall drive round together after luncheon.”

“Certainly,” I answered, and the conversation drifted away into otherchannels.

As we made our way to the hospital after leaving the Holborn, Stamfordgave me a few more particulars about the gentleman whom I proposed to takeas a fellow-lodger.

“You mustn’t blame me if you don’t get on with him,” he said; “I knownothing more of him than I have learned from meeting him occasionally inthe laboratory. You proposed this arrangement, so you must not hold meresponsible.”

“If we don’t get on it will be easy to part company,” I answered. “It seemsto me, Stamford,” I added, looking hard at my companion, “that you have

some reason for washing your hands of the matter. Is this fellow’s temper soformidable, or what is it? Don’t be mealymouthed about it.”

“It is not easy to express the inexpressible,” he answered with a laugh.“Holmes is a little too scientific for my tastes —it approaches to cold-bloodedness. I could imagine his giving a friend a little pinch of the latestvegetable alkaloid, not out of malevolence, you understand, but simply out ofa spirit of inquiry in order to have an accurate idea of the effects. To do himjustice, I think that he would take it himself with the same readiness. Heappears to have a passion for definite and exact knowledge.”

“Very right too.”

“Yes, but it may be pushed to excess. When it comes to beating thesubjects in the dissecting-rooms with a stick, it is certainly taking rather abizarre shape.”

“Beating the subjects!”

“Yes, to verify how far bruises may be produced after death. I saw him at itwith my own eyes.”

“And yet you say he is not a medical student?”

“No. Heaven knows what the objects of his studies are. But here we are,and you must form your own impressions about him.” As he spoke, weturned down a narrow lane and passed through a small side-door, whichopened into a wing of the great hospital. It was familiar ground to me, and Ineeded no guiding as we ascended the bleak stone staircase and made ourway down the long corridor with its vista of whitewashed wall and dun-coloured doors. Near the further end a low arched passage branched awayfrom it and led to the chemical laboratory.

This was a lofty chamber, lined and littered with countless bottles. Broad,low tables were scattered about, which bristled with retorts, test-tubes, andlittle Bunsen lamps, with their blue flickering flames. There was only onestudent in the room, who was bending over a distant table absorbed in hiswork. At the sound of our steps he glanced round and sprang to his feet witha cry of pleasure. “I’ve found it! I’ve found it,” he shouted to my companion,running towards us with a test-tube in his hand. “I have found a reagentwhich is precipitated by haemoglobin, and by nothing else.” Had hediscovered a gold mine, greater delight could not have shone upon hisfeatures.

“Dr. Watson, Mr. Sherlock Holmes,” said Stamford, introducing us.“How are you?” he said cordially, gripping my hand with a strength for