Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

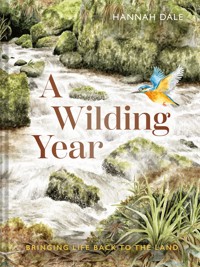

Follow Hannah Dale's deeply personal journey as she returns her Lincolnshire farm to nature, celebrating the return of an astonishing variety of wildlife. Hannah Dale, the artist and founder of the award-winning nature-centric gift company Wrendale Designs, takes you through a year on her farm in rural Lincolnshire where, alongside her husband, she has undertaken an ambitious rewilding project. Together, they are attempting to return the land to nature and increase the number of species their land is able to support. A Wilding Year explores how one family have been able to embrace the beauty to be found in untidy landscapes, heralding the return of skylarks, meadow pipits, hobbies, polecats and many more species to their farm. The land was originally claimed from marshy wetlands, and leaning into the land's natural inclination to be wet has also yielded amazing ponds and pond life. This rewilding journey has also provided Hannah with new sources of inspiration for her paintings. A Wilding Year is both a journal and a sketchbook, in which Hannah keeps a visual record of the incredible variety of species she finds on the farm. This fascinating account of a year spent in nature brings to life the beauty and power of wildlife in every season.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 208

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Introduction

In 2015, my husband Jack inherited a small farm in Lincolnshire. It was unexpected and unwanted – the result of his dad’s short and intense battle with a brain tumour that took a kind and inspirational man far too soon.

The land Jack inherited possesses in abundance what his dad affectionately referred to as ‘character’. Claimed from marshy wetlands by the drainage experts of the 17th century, it is stubborn ground that does not want to be cajoled into producing food for its human custodians. It is clear that the land wants to embrace its natural inclination to be wet, despite the best efforts of land drains and ditches. Much of it sits under water during the winter before the clay soil bakes hard in the summer, opening up deep fissures and strangling anything that tries to grow in its inhospitable tilth.

Despite the challenges, for the first few years we tried unsuccessfully to generate a profitable harvest from the land. The stress of watching the weather is an occupational hazard for all farmers, and it is invariably too wet, too hot, too cold or too dry at any one time, but the frustration of watching a crop of winter wheat drown under stagnant water, or trying to persuade a seed to germinate on dusty baked-hard ground, was painful and we started to think about other ways the land might be used.

In 2018, Jack read Wilding by Isabella Tree, a book that documents the transformation of an unprofitable arable farm over a period of 20 years into a rich mosaic of habitats offering refuge to a large number of species clinging on to the last vestiges of suitable territory that exist at the fringes of the environment we have shaped. The principle of ‘rewilding’ is to restore ecosystems to the point that nature can take care of itself and we both found the book and the concept incredibly inspiring. We felt that our poor, unproductive land was an ideal candidate for rewilding. Rather than losing money year after year trying to grow crops, it could be better put to use for the benefit of nature. We also felt that it was a fitting way to honour Jack’s dad, who loved the countryside and was an early pioneer of regenerative farming. He had spent a large part of his career developing a seed drill that negates the need for ploughing, thereby protecting the soil structure and preserving his beloved earthworms in the process.

As a wildlife illustrator and having studied Zoology at Cambridge University, I spend much of my time in the Lincolnshire countryside, and the idea of allowing our farm to stop fighting against its natural instincts and letting nature flow back in was incredibly appealing. Over the past few years, I can’t be alone in having experienced severe anxiety related to the climate and biodiversity emergencies that we are facing, and the catastrophic collapse of so many species that shows no sign of abating. The loss of wildlife abundance we have experienced in Britain has outpaced almost everywhere else in the world*, and a re-setting of expectations establishes a new baseline for each generation, meaning that we can’t even remember what we have lost. Far from being a stable situation, many species are still in free fall and without the protection that exists from being part of a large colony or connected, functioning ecosystem, the few isolated breeding pairs still clinging on to fragments of habitat that remain have little hope of recovery. Successful reintroductions and an overwhelming love of the natural world among the British people offer beacons of hope, but the slow response of government and denials from people who prefer to bury their heads in the sand or have vested interests in maintaining the status quo, are both frustrating and heart-wrenching.

In July 2019, we took the final harvest from our soil and tentatively stood back to see what would happen. We planted trees, dug ponds and scattered locally sourced, native wildflower seeds to try and replenish the depleted seedbank. Above all, we began allowing the land to express its own character, and to start the process of healing itself.

Ceasing cultivation, spraying and fertilizing is now allowing the regeneration of scrub, a vital habitat largely missing from our countryside. Within a few short years, our unfettered hedgerows are now festooned with blossom in spring and burgeoning with berries in autumn. The soils crawl and the grasses fizz with insects. In summer, clouds of meadow brown butterflies numbering well over a thousand billow over patches of creeping thistles. The birdsong in spring has exploded in volume as more food availability means more successful breeding seasons. Barn owls hunt over messy grass wriggling with voles where once a sterile bed nursed its monoculture of wheat, like a meadow pipit feeding a cuckoo chick in its nest that doesn’t belong there.

As an artist, our return to wildness has provided me with an unlimited source of inspiration, and spending time on the farm with a sketchbook provides both a cathartic relief from the stresses of daily life and a source of new paintings. My artwork has always been inspired by nature, interwoven with a dose of imagination for good measure and this book is both a journal and a sketchbook, capturing glimpses of the characters that have joined us here at Low Farm over the course of a year. I hope that bringing them to life in both words and art encourages more people to see beauty in an untidy landscape and to embrace a little more wildness in their lives.

_________________

* According to analysis of more than 58,000 species undertaken by the Natural History Museum that showed the UK has only half of its entire biodiversity left, putting it in the bottom 10 per cent of the world’s countries.

January

The sun is rising over a landscape chilled by an overnight frost. The skeletal remains of last year’s cow parsley glitters with ice crystals forming delicate crowns, each fragile spindle fortified by the cold. Desiccated thistles are transformed into spiny ice sculptures, with twisted and brittle leaves glistening, their wizened teasel heads bowed as the stems no longer have the strength to support them. The low sun is blindingly bright and casts long shadows as I walk across The Park towards the ponds. The last few months have been some of the wettest I can remember, and the farm is sodden, its clay foundations holding onto the water as it settles into the gentle undulations to form pools and channels stretching across the land. The surface of the puddles has iced over, a thin glass window beneath which the muddy grass suffocates and drowns. In the distance, a kestrel is laughing.

Against a pink-tinged sky, the thick hedgerows are sleeping, no signs yet of a spring awakening. Here and there clusters of berries cling like rubies to lichen-coated branches, but many have already been stripped by marauding mobs of winter thrushes. Over the past few years, the diversity and abundance of birds on the farm has acted like a barometer for the health of the land. As the habitats slowly begin to improve, the birds are returning to the farm and the volume of birdsong has audibly increased, along with the variety of voices that contribute to it. This morning, with the landscape deep in its winter hibernation, the birds are waking and the slumbering hedgerow jostles with life. A rowdy gang of goldfinches chatter to one another, perched like baubles on the bare branches at the top of a field maple, and the sad ‘seep-seep’ of a redwing cuts through a blackbird’s melody. Somewhere in the dense, tangled undergrowth a wren scutters, firing out its rattling call at a volume and intensity that belies its diminutive size.

My wellies crunch through the frost and I disturb a woodcock nestled among the grasses and brambles that skirt the bottom of the hedge. Its freckled plumage, stippled with earthy tones of brown and grey had rendered it invisible, and it startles me as it clatters out of the undergrowth, jinking left and right erratically as it escapes potential danger.

I love mornings like these. The cold needles at my cheeks but I’m cosy and warm inside my fleece and woolly hat. I clamber up the mound at the most western edge of the farm, formed from the spoil when we dug the ponds, which provides some moderate elevation in an otherwise flat landscape. I arrive at the top just in time to see a red fox clear the dyke and disappear into a neighbour’s field. From here I can see across The Park, over the hedgerows that flank the track and across to Benard’s Field and Lone Pasture. Today, the bottom two-thirds of both fields appear to be on fire, as vast pools of frozen water reflect the neon sky. A lone tree, an old ash that has somehow escaped the ravages of ash dieback, is the last remnant of a hedgerow that once ran across both fields, ripped up by the tides of progress and an urgent drive for more efficiency in farming that has characterized the last century. It owes its life, in part, to Jack’s brother Tom. Despite the inconvenience and time needed to manoeuvre heavy machinery around isolated trees, he always insisted that the remaining trees peppered across their land, standing lonely and majestic among seas of crops, were to stay. I have no idea why the farmers that took the hedgerow out in the first place decided that the ash was different from the other trees. Perhaps they liked the twisting branches that sprawled and spread out. Perhaps there was a tawny owl nesting deep in its hollow core and they spared it for the sake of the birds. Perhaps they meant to come back and finish the job but never got around to it. The ash sits on a ridge that crosses the land where the fields climb gingerly out of the watery lowland. From here, it’s striking how much variation there is in the vegetation that has started to colonize the land. Where we once tried to bully the land into uniform conformity, it is now free to express its own nature and the subtle differences in substrate and soils are reflected in the different plants that thrive there. Self-set copses of birch and sallow yield to coarse sedges and creeping buttercup that fade into a finer sward interspersed with the bare bones of young hawthorn and dog rose sleeping through their first or second winters.

For as long as I can remember, I have found my peace in nature. As a child, I spent hours alone in our small garden. I knew the smell and texture of every leaf. I learned which rocks to turn over to find wood lice and centipedes. I could tell which flowers the earwigs preferred, under which wooden windowsill I would find a butterfly’s chrysalis suspended, and where to avoid sitting on the lawn if I didn’t want to end up bitten by the red ants that nested in the grass. I knew every bush that housed an old nest and the birds that built them. I marvelled at the feather, mud and moss linings. I crept out after dark to greet a hedgehog that lived under an old yew tree and counted the spots of ladybirds. When I wasn’t outside looking at nature, I was inside drawing it. My mum kept hundreds of drawings and paintings that I had done over the years, and it wasn’t until I found them after her death years later, that I realized how much my childhood passions had foreshadowed the career I thought I had fallen into by accident and circumstance. Quiet, studious and sometimes a little lonely at school, I won a place at Cambridge to study Zoology and finally found myself among people who shared my intense curiosity for the natural world. I loved every minute and every aspect of my degree. I loved the academic side, reading cutting-edge research that unlocked scientific mysteries; I loved the fieldwork where I would always have a sketch book and pencil with me; and I loved the social side, finally discovering a confidence that had eluded my earlier teens. This newfound confidence, combined with a fiery ambition that had always burned inside me, propelled me towards London after graduating to pursue a shiny and exciting career in the City. I lasted five years before limping back to Lincolnshire, exhausted and homesick.

For as long as I can remember, I have found my peace in nature. As a child, I spent hours alone in our small garden. I knew the smell and texture of every leaf.

Within a year of coming home, Jack and I were married, had our first child and my mum was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Suddenly everything changed. I needed a job that would fit around a baby and allow me to spend as much time with my mum as possible. I turned back to what I knew best – nature and art. After a few years of trying different ideas, Wrendale Designs in its current form was born. Watercolour illustrations of wildlife, printed on beautiful-quality, sustainably sourced greeting cards was where it started, and within a few years the collection had grown and we were selling home and giftwares all over the world. The opportunity to return our farm to nature felt like the closing of a circle. It was an opportunity to ‘give back’ to the animals and birds that had always inspired me and my artwork and a deep and primal feeling that this was the right thing to do.

In my forties, I’m haunted by worries that never darkened my youthful thoughts. The world seems a terrifying place. I fear for the future my children will have to face if we fail to address the climate crisis, the collapse of nature that we are careering towards with alarming certainty, and the chaos that will ensue as a result. A sense of helplessness and frustration with the wanton and careless destruction of nature feeds a despair that is hard to control, but out here the cold air, the birdsong and the sunrise pour a soothing balm over the seething anger that sometimes threatens to overwhelm me.

As the last vestiges of darkness begin to fade, a large, pale bird silently coasts across The Park on broad, rounded wings. A ghost. It glides seemingly weightless across the field, surveying for the smallest rustle that will yield the location of an unlucky field vole or mouse. The slow cadence of its wing beats lifts it over the hedge into Fox Cover before it circles back, low and quiet over the frosty grass. It alights on a fence post where it rests for a while, its watchful eyes coal black studs in its flat, heart-shaped face. Barn owls are perfectly adapted to silently hunt their prey. They have large wings relative to their low body weight (known as low wing loading), which allows them to fly slowly, giving them time to detect prey as they glide along. They even have tiny hooks along the feather at the leading edge of the wing that help to deaden the sound of air hitting it. Although their eyes are adapted to work well in the dark, experiments have shown that barn owls are perfectly capable of catching prey in complete darkness, using sound alone. Their heart-shaped faces direct sound into their ears and they have among the most sensitive hearing of any animal. Before long the owl abandons its perch and disappears over the hedge towards the track. When we built a pole barn a few years ago, we installed high, flat platforms in the eaves for barn owls, and we often find pellets in there from owls and kestrels who also take advantage of its shelter. I wonder if it has gone there to roost now the sun is rising higher in the winter sky. I head back to the house, restored and refreshed. Not a bad way to start the new year.

February

I’ve always been a morning person – a lark rather than an owl. My most productive hours are the early ones before anyone else in the house has stirred. I often wake several hours before the alarm, my mind immediately flitting to whatever painting I’m working on. As soon as this happens, I know that sleep won’t return and I totter downstairs in slippers and dressing gown, make a coffee and head to my work room. This morning, my brain has decided that I have had enough sleep by 4.30 am and I suddenly have a craving to be outside. I put on my coat and wellies over my pyjamas and grab my binoculars. The night has been mild and clear. The moon is large and full, a milky orb resting on a wisp of migrating cloud. Pale, white moonlight washes across the landscape and forms long, eerie shadows. They streak over the familiar surroundings like cold fingers probing into every crease and fold.

I walk towards Fox Cover along the track, flanked by abundant hedgerows and a tangle of brambles. The daytime soundscape is filled with the melodic song of blackbirds, thrushes and robins, interspersed with the ubiquitous rattle of Jenny wren. In the dark it is transformed. A pair of tawny owls duet, the male’s fluting vibrato answered by the female’s shrill ‘kee-wick’. Little owls are shouting at one another from their perches in trees nestled along the hedgerow. The screeches and hoots are suddenly upstaged by piercing screams. Somehow human and other-worldly at the same time, the mandrake-like shrieks are shocking in their volume and intensity. Rounding the corner of Fox Cover, I crouch among the gnarled roots of an old oak tree and the moonlight betrays the source of the screaming. It is mating season for foxes and this unearthly overture is their idea of a love song. A pair are cavorting in the field, flirting and teasing one another. They pounce and play fight like cubs, all part of the courtship ritual that will continue for weeks before mating occurs. Foxes are monogamous and often pair for life. These behaviours help to reinforce their bond, important in foxes as both parents will play an active role in raising their young. They eventually disappear over the bridge into The Park. This pair successfully raised three cubs last year in an earth conveniently excavated for them by a clan of badgers, the two species quite happily rubbing along together.

Across the field, a pair of roe deer are browsing and a badger snuffles for worms. Dozens of rabbits are going about their business and every so often a snipe or a woodcock senses my unwelcome presence and flushes out of the grass. This shadowy nocturnal world is entirely different from its daytime incarnation. Dewy damp thickens the air and an earthy, mossy smell pervades. My skin tingles with a nervous energy as I intrude where I don’t belong. During the day, these nocturnal creatures reveal themselves only in tantalizing, fleeting glimpses. They are emboldened by the darkness and this world is theirs. I am a voyeur. I creep back down the track towards the house, exhilarated and inspired.

Later that day I take the same journey down the track towards Fox Cover. The air is filled with the orchestral harmony of songbirds and a green woodpecker yaffles away in the wood. Across the field, a flock of meadow pipits forages for insects, and skylarks have woken up, flinging themselves vertiginously into the air before floating down in full song.

As I cross over the badger sett by the bridge into The Park, I think of them asleep under my feet, waiting for nightfall to reclaim the farm once more.

* * * * *

It has felt like a long winter this year. The thrill of cosy evenings curled up by the fire has long since worn thin and it’s a relief to see the first signs of spring emerging. Swathes of snowdrops nodding their elegant heads have appeared in bright clusters and the shoots of daffodils stand straight like little soldiers waiting for their turn to burst into flower.

The weather has been wintry over the past few weeks – a sustained frost followed by several days of strong winds made it difficult for the barn owls to hunt and I’m dismayed to come across the remains of one on the edge of Church Wood. It’s the most deadly time of year for juvenile barn owls as vole numbers are at their lowest – around 70 per cent die in their first year and these inexperienced birds struggle the most during severe weather conditions. Even knowing that the odds are stacked against them, it’s dreadful to think that there is one less of these beautiful birds on the farm.

The hazels in the wood are bedecked with catkins, dangling from the branches like little lamb’s tails. I’ve come to the hazel copse at the edge of Church Wood to see whether I could find a little magenta-coloured treasure easily missed by an unknowing observer. Sure enough, at the end of each shoot adorned by catkins is a tiny flower with hot pink, spiky stigmas like some kind of punk sea urchin. Hazels are monoecious, meaning that they have separate male and female flowers. Unlike plants that rely on insects to pollinate them, the hazel has no need of showy petals or intoxicating scent to attract the attention of passing pollinators. Instead, each catkin contains more than 200 male flowers that release clouds of pollen into a passing breeze that carries it away to neighbouring hazels where it can pollinate the little pink female flowers.

Beyond the wood, another species is making its presence known. A speckled brown bird, slightly smaller than a starling with a tufty crest upon its head, the skylark looks unassuming until it unveils its superpower. Soaring vertically into the sky before exploding into a cascade of melodious song while suspended in the air, it floats down like a parachute held aloft by the buoyancy of its song alone. Skylarks, once a common sight across farmland, are disappearing rapidly and, along with so many other species, their numbers in free fall. A lover of tussocky grass pastures, we’ve seen large flocks amassing over the past few weeks and now the birds are pairing up and the males have begun their display. It is thought that the energy needed for these eccentric behaviours is a good indicator of the fitness of the males, helping the discerning females to choose a suitable mate. Creatures of habit, skylarks return to the same area every year, and it’s lovely to see such an abundance of them here on the farm showering their liquid warbles down from the sky. It is little wonder that these birds have inspired so much poetry and art and I am deeply saddened that so few people are able to experience their song in depressingly vacant expanses of our countryside.

It’s a lovely day to be out sketching and I estimate there are around 80–90 skylarks displaying and filling the air with a continuous stream of mellifluous song. They pause between performances, sitting on the fence line among reed warblers, yellowhammers, chaffinches, stonechats and buntings. I’m totally immersed in my work, peering through my binoculars, every sense stimulated. All too soon, reality beckons with the impending school run drawing closer but I close my book feeling lifted and refreshed, the birdsong still echoing in my head.

March

It’s chilly and damp but there are signs everywhere that spring is jostling to take over from winter. Swollen leaf buds adorn bare branches, full of the promise of verdancy just around the corner. Snowdrops are tired and withered after their early exertions while delicate crocuses are enjoying their time in the sun and fresh shoots, bold with the confidence of youth, are emerging everywhere. The hedgerows are already full of birdsong, the melancholy fluting of song thrushes providing a backdrop for the robin’s soprano, while a wren loudly demands to be heard.

Over at the sett, the badgers have been indulging in some spring cleaning. Bundles of discarded bedding have been dragged out and abandoned in jumbled piles. It’s likely that somewhere underneath my feet the sows are tenderly nursing their newly born cubs who will stay safely tucked away in their subterranean cocoon until April.