35,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

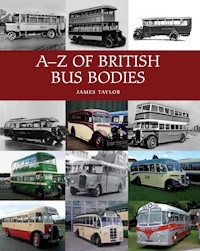

A-Z of British Bus Bodies sets out to offer a first port of call for anyone with an interest in those who built bus and coach bodies in Britain and Ireland between 1919 and 1975. From charabanc to service bus, from luxury coach to municipal double-decker, the sheer variety of public service vehicle (PSV) bodies is astonishing.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 398

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

A–Z OF BRITISH

First published in 2013 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

© James Taylor 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 639 0

CONTENTS

List of Abbreviations

Part 1 INTRODUCTION

THE SCOPE OF THIS BOOK

CONTEXT AND BACKGROUND

Part 2 THE A-Z OF BRITISH BUS BODIES

Appendix: Operator-Built Bodywork

Index

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

It is standard practice to use abbreviations to describe bus-body configurations. The abbreviations were developed in the 1950s and have been continuously adapted since to meet changing circumstances. Some of them will be found in this book and so, for readers not familiar with them, they are listed below.

A typical abbreviation breaks down into three main groups. For example, in the abbreviation H56R, the figure in the centre is the seating capacity and the letters on either side indicate other features of the bodywork. (Note that on double-deck bodies, the figure may be subdivided, for example H30/26R, which would indicate thirty seats on the upper deck and twenty-six on the lower deck.)

Before the seating capacity figure:

B

Single-deck bus (stage-carriage type)

C

Coach

Ch

Charabanc

DP

Dual-purpose single-deck (suitable for bus or coach operation)

F

Full-front where not normally fitted, such as on vertical-engined models; this letter may precede others, as in FC35F

H

Highbridge-type double-deck, with centre upper-deck gangway

HD

Half-deck or ‘observation coach’ type, with rear seats on a higher level than front seats

L

Lowbridge-type double-deck, with sunken side gangway on upper deck to permit lower overall height

O

Open top; this is used for both double-deckers and single-deck saloons

T

Toastrack (open-sided single-deck type)

U

Utility type, built to 1942–5 Ministry of Supply specifications; this letter may precede others, as in UH56R. This abbreviation has largely fallen out of use today

After the seating capacity figure:

C

Centre entrance

D

Dual entrance

F

Forward entrance (front-engined types) or Front entrance (underfloor-engined types)

R

Rear entrance

RD

Rear entrance with platform doors

RO

Rear entrance with open rear staircase

T

Toilet compartment fitted; this letter may follow others, as in C28FT

Part 1 INTRODUCTION

THE SCOPE OF THIS BOOK

This is the sort of book I wish I had been able to find when I was first interested in buses in the late 1950s. Enthralled by references in the pages of Buses Illustrated and by the sight of unusual bodies while on holiday trips around Britain, I wanted to know more about the companies who had built these buses and coaches. It was not hard to find out more about the chassis makers, even defunct ones such as Crossley or Gilford, but there seemed to be no source of reference to tell me about Heaver, Samlesbury, Waveney, Welsh Metal Industries and the like. In fact, only the most basic information about the big names such as Duple, Harrington, MCW and Park Royal seemed to be available in those days.

When I came to prepare this book, I discovered that there were far greater numbers of public service vehicle (PSV) bodybuilders in Britain than I had imagined. That made the task of writing it harder, but more interesting as well. Since I first became interested in buses, of course, a great deal more information has become available both in print and on the web, and it would be wrong of me not to acknowledge how important that has been in putting this book together. Somebody once said that we only think we are tall because we stand on the shoulders of giants and that is a particularly good way of explaining how I feel after preparing this book. The legendary names in the bus enthusiast’s world are too many to list here, but they have definitely been the giants.

Right from the start, I should explain that this book is in no way intended to be the definitive reference source to its subject. Such a book would require another lifetime or two to prepare and would run to many volumes. The aim of this book is to make the entry for each coach-builder into a succinct summary of what is known, that is, enough to satisfy the merely curious, but also a starting point for those interested in discovering more. And there is more – much more – to be discovered. There are still many constructors of PSV bodies who have been only imperfectly identified, or not identified at all. This is particularly true of the 1920s period, but frustratingly true also of a favourite period of mine, which is the late 1940s and early 1950s.

There are very many companies who are known by little more than their name and a date, and I debated long and hard about whether to include them or not. In the end, I thought that I should – discovering that some trace of a company has been recorded is better than finding it absent from these lists, even if the information recorded is not very enlightening. Where information is extremely limited, however, I have wielded an editorial pencil. So I hope that readers will understand that where an entry simply indicates that a company ‘constructed single-deck bodies in the late 1920s’, it is an invitation to further research on the subject. On that score, if any readers are able to add information or corrections to what is in this book, I would be delighted to hear via Crowood. I will add any new information of substance to a second edition, if one is published.

As the book’s title implies, it covers bus and coach bodybuilders who were active between 1919 and 1975. Some of these may only just have crept into the period, so a company that had been active before World War I, but closed down in 1919, would be included. Many companies listed continued in business after 1975; their entries acknowledge this, but generally give only a brief mention of their later activities.

In order to keep the lists within manageable proportions, I have deliberately restricted their scope in some areas. Companies responsible only for minibuses or minibus conversions have been excluded and those that built only welfare-type or works bus bodies are also not listed. Several operators constructed bodywork for their own use in their own workshops; these have also been excluded, unless they also built bodies for other operators as well. However, there is a list of them in the Appendix at the back of the book. Finally, I have included companies based in the Republic of Ireland where information has been available, even though many of them did not sell their products outside their own country.

A book like this cannot provide fully detailed histories of every single PSV bodybuilder within its chosen limits. However, it can offer a first port of call for anybody who wants to know a little more about a company, as well as an encouragement, perhaps, to pursue further research. There are many excellent books on individual coachbuilders to be had, most of them compiled by dedicated enthusiasts. Though they tend to have small print runs and are not always easy to find, typing the name of a coachbuilder of interest into one of the online book specialist sites will very often uncover a copy for sale.

SOURCES

I have put this book together from a huge variety of sources, beginning with my own observations going back to the late 1950s and early 1960s. I have of course drawn on very many books, many written by highly respected PSV authors and some written as one-off labours of love by dedicated enthusiasts. There are so many of these that it would be impossible to list them all; I would not claim to have read all those available, either, and of course there are new ones appearing all the time. However, it is important to make quite clear here that this book relies heavily on the wonderful research that has gone into so many of them and in that respect I make no claims to originality.

I have also gained information from a large number of magazines, most notably Commercial Motor, Bus and Coach, Buses (and its forerunner, Buses Illustrated). Particularly useful have been the Commercial Motor online archive at www.archive.commercialmotor.com and some of the PSV Circle publications devoted to bodybuilders. I have made extensive use of archives held by the Omnibus Society, the Kithead Trust and the British Commercial Vehicle Museum (BCVM), although I would not claim by any means to have gleaned every scrap of information that may be available there. The internet has been a further source and information has turned up in some of the wonderful sites fed by reminiscences (such as Old Bus Photos), in some of the more serious sites dedicated to recording fleets (Ian’s Bus Stop and the Peter Gould material at www.petergould.co.uk), and even in local history sites not otherwise interested in anything to do with the PSV world.

Photographs have come from a number of sources, including the BCVM, the R.C. Davis Collection (now held by the Omnibus Society), the Kithead Trust, Nick Larkin, Roy Marshall, the Omnibus Society, Ron Phillips, the late Brian Smith (via the Canvey Island Transport Museum), the Peter Davis collection (now held by the Omnibus Society) and my own collection. In a small number of cases, it has not been possible to discover the identity of the original photographer despite best efforts; sincere apologies here if any reader feels slighted and I would aim to put the matter right if this book goes to a second edition.

About halfway through turning my mass of notes into a book, I also discovered in the Omnibus Society archives a wonderful typewritten document that listed bus and coach bodybuilders. I have since learned that this was put together by Derek Roy of the PSV Circle, as an aid to the Circle’s sub-editors. His painstaking work has contributed a great deal of detail to my own book and if I had discovered the document earlier, I would have had to put in a lot less effort!

Finally, thanks go to Nigel Furness for reading through the manuscript at an early stage and providing constructive criticism; to Tom Clarke, who provided last-minute help on his speciality, Gurney Nutting; and to the Omnibus Society itself, whose members’ formidable knowledge has made this book far more accurate than it otherwise might have been.

CONTEXT AND BACKGROUND

In Britain as elsewhere, the business of building bodies for public service vehicles (PSVs) grew up separately from the business of building chassis for those vehicles. The reasons were simple. Many of the bodybuilders had started life in the days of the horse-drawn vehicle and their specialism was in constructing sound and attractive bodies, to which the addition of axles was a mere accessory. The chassis makers, on the other hand, mostly had very different backgrounds. Their expertise was in things mechanical, notably in engines and gearboxes; mounting these on a ladder-frame chassis was a secondary part of their activity. The two types of manufacturer needed one another, but there was no pressure in the beginning for them to amalgamate and thereby produce complete vehicles. Although some of the chassis makers did turn to making complete vehicles, they were in the minority.

The early years of the twentieth century saw some quite fierce competition, with chassis imported from continental Europe vying for custom with home-built types. Yet the bodies were almost invariably made in Britain to suit local requirements. The Great War of 1914–18 brought some great strides in the technology of road vehicles, with body makers and chassis manufacturers subsequently enjoying a period of peaceful co-existence for half a century or more.

However, things were changing. As the market for buses and coaches began to contract during the 1950s, a battle for survival began. At first, it was characterized by mergers and by the failures of the smaller companies. Then, as the pressures became more intense, the move towards integral construction (bodies that carried their own running units and had no separate chassis frame) gathered momentum. The major steps were made at the end of the 1960s, with those body makers who had not joined the trend finding themselves in difficulties.

By the middle of the 1970s, the integral bus and coach had become the norm and the old distinction between body maker and chassis manufacturer had largely disappeared. At the same time, continental European manufacturers had begun to exploit the gaps that were developing in the British market. By the later 1970s, the bus bodybuilding scene in Britain had changed forever and it is at that point – actually a period rather than a clearly defined date – that this book closes its coverage. For the sake of convenience, the cut-off date chosen is 1975.

CONSTRUCTING A BODY

A 1938 publication issued by Duple shows the bodybuilding process of the time from start to finish and helps in understanding what happened at this major coach-builder. Obviously, smaller companies operating from less spacious premises had less sophisticated methods, but the essential principles would have been the same. In 1938, all Duple bodies were of composite construction and the company prided itself on invariably delivering completed vehicles on time.

When a customer’s chassis reached the Hendon works from its manufacturer, the first job was to strip it of all electrical and loose equipment. Once the chassis had reached Duple, it would not move again under its own power until it had been completed; tractors were used to move unfinished vehicles from one department to the next.

The Drawing Office prepared a full-size drawing of the agreed body design. This drawing then went with the vehicle through the various stages of manufacture, to avoid the need for departmental foremen to make constant visits to a central Drawing Office. The completed drawing was accompanied by full workshop schedules, itemized with instructions for each department involved in the construction of the body. When the job was completed, all the information was recorded so that a repeat order or a request for replacement sections could be dealt with immediately. Amendments to the original instructions were also recorded, on special coloured amendment sheets.

The sections of the wooden framework were roughly prepared in the Mill, before passing to the adjacent Setting-Out Department. It was here that jigs were formed, wood was shaped and the mortises and tenons required to join one section to the next were prepared. Meanwhile, the metal and metal-reinforced elements of the composite bodywork – bulkheads, wheel arches, cross-members, skirt rails, and so on – were fabricated in the Smithy and Fitters’ Shop.

The elements of each body were then taken to the Body Assembly bays, where the new body began to take shape. Each body was assembled on a jig, or on body trestles. The base, bulkhead, sides, rear end, roof, cab and doors were all put together to form the body frame or skeleton.

The body frame then moved to the Erection Shop for mounting to the chassis. Here, it was clothed with sheet metal panels formed and beaten in the Sheet Metal Section. Once fully panelled, each vehicle moved on to the Paint Bay. This was essentially a large workshop where the air was changed every three minutes to prevent contamination and to reduce the presence of dust particles. Some panels, such as mudguards, would be sprayed off the vehicle.

Meanwhile, the vehicle’s interior trim and seats were being prepared in the Trimming Department and Seat-Making Section. The customer would have specified a particular style of seating and upholstery, choosing a moquette from stock patterns that were kept in books.

Each completed vehicle then moved to the Finishing Bays. Here, any remaining loose parts or electrical items removed when the chassis had been delivered were refitted. The vehicle then passed over an inspection pit where it would be examined by a Certifying Officer from the Ministry of Transport, who would issue a Certificate of Fitness if he was satisfied. Clients were also invited to inspect their new vehicles at this stage if they so wished. From there, the completed vehicle was passed to the Delivery Department and on to the customer.

Chassis arriving at the Duple works in Hendon, 1938. They would have been driven there by road from their manufacturers. An AEC Regal and a Dennis Lance are seen here.

A full-size body drawing is prepared in the Duple Drawing Office. The date is 3 March 1937; the body is for an Albion chassis.

THE 1920s

The decade following the end of the Great War in 1918 was one of expansion in the bus business, and in the coach business too. Municipal authorities began to see the advantage of the motor bus (and also the trolleybus) as a more flexible alternative to the tram. In rural districts, demand for small service buses increased as these became a popular alternative to the train. And as the nation gained a taste for day trips and longer tours, demand also rose for more comfortable vehicles, the distant forerunners of today’s coaches.

Chassis builders responded as best they could, but there was a shortage initially, so many military lorries that had survived war service were refurbished mechanically and fitted with bus or coach bodywork to meet demand. From the middle of the 1920s, imported American chassis helped meet demand, too. All this created an additional demand for bodywork and after 1919 many small local businesses turned their hand to bus and coach body construction, often combining it with building van and lorry bodywork, and even car bodies as well. Others were established from nothing, often by men returning from service in the Great War and eager to set themselves up in business.

Timber preparation was carried out in the Mill, where wood was cut to size.

The major national bodybuilders had not yet become established and it was common practice for operators of all kinds to patronize local companies if they could. There was good business to be had by securing orders from municipal authorities, which tended to want large batches of buses to the same design in order to simplify servicing and spares. However, there was also a reasonable living to be made by supplying bodywork for local independent operators and, as a result, dozens of small companies turned to this. There were also as yet no nationally agreed standards governing bus construction and, as local authorities had the last say on what was and was not permitted, the firms who constructed bus bodies found it easier to keep to a fairly local clientele.

Some of the small companies, inevitably, built no more than a handful of bodies, in some cases perhaps no more than one. Records in many cases are sketchy or non-existent and, despite the diligent research that has been done in this area, the picture we have today is far from complete. That explains why, in this book, some of the smaller companies from this period are recorded in no more than a few lines.

This was the Setting-Out Department, where timber sections were shaped and joints were cut.

At the start of the 1920s, chassis typically stood high off the ground, with the result that most bodies seemed very tall. Designs were mostly functionally boxy, with little to distinguish one maker’s products from another’s. By the middle of the decade, lower single-deck chassis (such as the 1925 Leyland Lion) began to bring overall heights down.

Most new buses – and, of course, coaches – in the 1920s were single-deck types. Double-deckers were relatively uncommon in rural areas. Height and safety concerns were an issue; even though many large towns and cities were used to double-deck trams, the thinking was that a bus could swerve or manoeuvre quickly in the way that a tram could not and so risk overturning. Even in London, enclosed top decks were not permitted before the mid-1920s, the thinking in this case being that the weight of a fixed roof added to the potential instability of the vehicle.

Then from 1927, a new generation of lower double-deck chassis came on to the market. Spearheaded by the Leyland Titan and followed two years later by the AEC Regent, these allowed further development of the double-decker in ways that had simply been impossible before. Leyland in particular pioneered an ultra-low height design of body, for which there was a ready market because of the large number of low railway bridges in Britain. This had the upper-deck gangway on one side instead of in the centre, so that it impinged on headroom above the downstairs seats rather than the downstairs gangway. The design was known as the lowbridge type, for obvious reasons, and was widely copied after Leyland chose not to renew its original patent. At the start of the period, single-deck service buses tended to be tall and boxy, with fixed roofs. Independent coach operators meanwhile favoured charabanc bodies for day trips and tours in the summer. Like many cars of the period, these were roofless vehicles with no weather protection. However, the great British weather was rarely predictable, even in the summer, and many charabancs were fitted with canvas roofs that could be erected over the passengers when the rain came. There were also ‘all-weather’ types, which benefited from side windows, front and rear domes, plus a folding roof.

More or less in parallel with similar developments in the car bodywork field, the fully enclosed coach body followed, typically with a folding or sliding ‘sunshine roof’ that could rapidly be opened or closed to suit the weather conditions. Forward entrances became popular on coaches, although rear entrances were more common on service buses. Some service-bus operators ordered bodies with both forward and rear entrances, to improve the flow of passengers through the bus at stops.

The metal elements of the body – mostly steel – were prepared in the Smithy and the Fitters’ Shop.

The later 1920s also saw new features on coaches, intended to afford greater luxury and so attract custom from rival operators whose vehicles were less well equipped. As early as 1925 there were toilet compartments on some long-distance coaches; the luxury elements came from such things as plush furnishings, veneered wood, quilted roof linings and curtained windows. Some coaches had kitchens; some were equipped as ‘sleepers’, with reclining seats; others were ‘radio coaches’, allowing passengers to listen to radio broadcasts – which in those days of course all came from the BBC.

Two photographs showing the Body Assembly Department, where the frames were put together.

THE 1930s

During the 1930s, bus and coach bodybuilding became a more specialized business. Many of the small firms that had been established in the flush of enthusiasm that accompanied the 1920s had not lasted the distance and many of those that had survived had done so by attracting business nationally rather than only locally. Even so, many operators, both municipal and private, still tended to patronize local suppliers when they could. Now, the introduction of national Construction and Use Regulations in January 1931 ensured that bodies built in one part of the country would meet requirements in others, thus encouraging more bodybuilders to seek new business further from home.

Body frame subassemblies are seen nearest the camera and behind them body frames are mounted to chassis in the Erection Shop.

Body design generally made great advances after the late 1920s. As chassis became lower, so bodybuilders finished the job off by extending the lower panelling downwards to conceal the chassis frame, exhaust system, fuel tank, battery box and other mechanical items. Buses and coaches looked more of a unit and less like a body perched on top of a frame with axles.

Body construction methods began to change, too. In the 1920s, bodies had mainly consisted of a wooden framework to which metal panels were attached by nails or screws (the Weymann system used fabric panels, but was relatively uncommon on PSVs). Now, several firms began to offer metal-framed bodies, which brought considerable advantages in durability. However, the victory of the all-metal body over the composite type was far from complete at this stage and it would not become so until the early 1950s.

Double-deck bodies became very much more popular, as some municipal operators began to replace their tram fleets. On double-deck bodies, the staircase moved inside the main bodywork at the start of the decade and full-length top decks superseded the type that stopped short behind the driver’s cab. Some operators evolved their own distinctive styles – for example, those operators affiliated to the BEF (British Electric Federation) had their favourite styles constructed by more than one maker. So companies like Brush, Roe and Weymann often built bodies to their individual interpretations of particular styles. These individual interpretations made many manufacturers’ bodies instantly recognizable. In the early years of the decade, six-bay construction (with six windows on each side downstairs) was the norm on two-axle chassis; by the middle of the 1930s, most makers had moved to less fussy-looking five-bay designs.

BUS OPERATIONS IN IRELAND

The Irish Republic

After the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, a number of bus service networks sprang up all over the country. There was intense competition at this stage and the railways, seeing a threat to their own service networks, rushed to set up bus services in competition.

Legislation was needed to bring the situation under control, with the Road Transport and Road Traffic Acts of 1932 and 1933 being designed to do just that. By the middle of the decade, the vast majority of services were run by four statutory operators: the Dublin United Tramways Company, the Great Northern Railway (GNR), the Great Southern Railways and the Londonderry & Lough Swilly Railway. The number of independent operators was reduced to around thirty and their business was almost exclusively local.

The next major change came on 1 January 1945, when Córas Iompair Éireann (CIÉ, the Irish Transport Company) was established under the 1944 Transport Act. The Great Southern Railways and the Dublin United Transport Company (as it now was) amalgamated, remaining a private company until nationalized under the 1950 Transport Act.

Meanwhile, the GNR ran into profitability problems and was jointly nationalized by the Governments of the Republic and of Northern Ireland. In 1958, the Great Northern Railway Act then divided the GNR into two. CIÉ took the services south of the border, while those north of the border went to the Ulster Transport Authority. CIÉ remained responsible for all bus, coach, railway and canal operations until 1987.

Northern Ireland

During the 1920s, there were many small independent operators in Northern Ireland, plus a small number of larger ones. The situation was controlled by the November 1926 Motor Vehicles (Traffic and Regulations) Act, which introduced minimum standards. Meanwhile, the railway companies had begun operating bus services in order to protect their market and in 1932 three of them (the Belfast & County Down Railway, the Great Northern Railway and the Northern Counties Committee) asked the Government to grant them a monopoly of road services in Northern Ireland.

Their wish was granted, with a small number of exceptions and exemptions, by the Road and Railway Transport Act in July 1935. From October 1935, the new Northern Irish Transport Board (NIRTB) gradually absorbed most other operators, with the situation remaining like that until 1948, when the NIRTB was merged with the railways as the Ulster Transport Authority. The road services were then passed to a new holding company in 1966, before coming under the control of Ulsterbus in April 1967.

Two scenes from the Sheet Metal Section, showing panels being prepared and fitted to vehicle frames.

Single-deck bus bodies were generally quite functional in appearance, although also more resolved as designs than those of the previous decade. But by the late 1930s, economic necessity had led to the development of dual-purpose single-deckers. These had enough seats to work as service buses during the week and enough luxury to act as coaches on summer weekends; they were often regularly used on the longer stage-carriage services as well. That way, a vehicle could be kept in service all year round rather than simply being mothballed for the winter when demand for coach tours was low.

Coach bodies were initially based on the bus designs, simply offering more comfortable seats with more leg room, but special coach shapes soon began to appear. Bodybuilders tended to have a basic standard design, but were more than willing to make variations to suit an operator’s tastes. As the idea of the luxury coach developed, there were some quite remarkably individual designs on display at the annual Commercial Motor Show. Some were designed as much to show the maker’s skill as anything else and remained unique.

One way or another, the design of coach bodies in the 1930s became far more varied; fashions also changed as the decade progressed. From about 1934, the vogue was for body trim details that reflected the latest public interest in streamlining. Shortly after that, there was a vogue for stepped waist rails. The luxury features pioneered at the end of the 1920s were still in evidence and some new designs also appeared. Notable was the ‘observation coach’, with the rear half of the seating set above the front half in order to give their occupants a better view forwards. Underneath, the body space vacated was made available for luggage, which helped to explain why these designs were often used on airport duties.

The vogue for streamlining did not only affect single-deck coaches. Several municipal authorities adapted the trimmings of streamlining to create very attractive liveries for their vehicles and some had double-deckers specially built to incorporate some of the principles of streamlining. Although sloping fronts hardly improved a vehicle’s aerodynamics, they did look the part, especially when combined with full-fronts, where the space alongside the driver’s cab was covered in to become part of the bodywork. Blackpool Corporation developed a very distinctive style with all these features, plus an unusual central entrance, and had it made by their local bodybuilder, H.V. Burlingham.

Double-decker capacity increased in this period, too. At the start of the 1930s, the typical double-decker had forty-eight to fifty-one seats; fifty-four seats soon became common, with fifty-six the norm by 1940. During 1939, Coventry Corporation took some sixty-seaters built locally by Metro-Cammell; their lightweight all-metal bodies allowed the extra passengers to be accommodated within the weight regulations governing bus manufacture at the time.

THE 1940s

During 1940, all bus production in Britain was halted as the Government redeployed factories and resources in support of the war effort. Bus bodybuilders were sources of skilled labour and that skilled labour – and the factories where it worked – typically found itself building or repairing aircraft and aircraft components.

The Paint Shop: some panels are being sprayed off the vehicles.

None of that diminished the demand for new buses, of course. Older examples continued to wear out just as quickly as before; indeed, often more quickly because skilled maintenance staff had been thinned out by the demand for soldiers, sailors and airmen. There soon arose an urgent need for replacements. The Government’s first response was to permit buses to be built from parts in stock and from part-completed vehicles on which work had been stopped. These ‘unfrozen’ vehicles were all to pre-war designs and were completed in 1941.

The next stage was the design of a stripped-out ‘utility’ specification, which would impose a common design on multiple manufacturers. Bodies used wooden frames to conserve metal for military machinery (although there were exceptions) and their simplified shapes did not require skills such as panel beating. Steel panels were used to conserve precious aluminium for aircraft, so making these bodies both heavy and rust-prone.

The prototype utility double-decker was built in October 1941 on an ‘unfrozen’ Leyland Titan TD7 chassis for London, but Park Royal built the first volume-produced example in 1942, on a Guy Arab chassis. Other bodybuilders gained permission to follow suit. Nevertheless, there was room for some individual interpretation within the standard outline and the bodies were far from standardized. Brush, BBW, Croft, Duple, Massey, Northern Counties, Park Royal, Pickering, Roe and Strachans were the permitted builders, with each adding their individual touches. There were ‘utility’ trolleybuses as well as motor buses, and both lowbridge (L27/28R) and highbridge (H30/26R) bodies. Seats were thinly upholstered into 1943, when wooden slatted seats took over. Upholstery was permitted again from mid-1945. Most ‘utility’ bodies had only one opening window on each side for each deck and the early ones had no window in the top-deck emergency exit.

These two scenes from the Trim Shop show work progressing on the seats and interior trimming.

These were the Finishing Bays, where the final touches were applied to new vehicles.

As for single-deckers, a standardized service bus design was built by Duple, Mulliner, Roe and SMT on the only chassis available – the Bedford OWB. There were no new coach bodies at all between 1940 and 1946. Many older chassis were also rebodied to ‘utility’ specification during the war. Beadle, Burlingham, Croft, East Lancs, Eastern Coach Works (ECW), Northern Coachbuilders and Reading all took part in this area of activity.

In all, around 6,700 ‘utility’ bodies were built between 1942 and 1945. Part of the deal had been that builders were allowed to use up stocks of parts before switching to utility construction and both East Lancs and ECW managed to get through the whole war without building utility designs; Beadle only ran out of old-stock parts towards the end. But the return of peace did not mark a return to the pre-war status quo in the bus manufacturing industry, which for the rest of the decade went through one of its toughest – and most interesting – times.

There had obviously not been anywhere near enough utility buses to go round and in any case the combination of their simplified construction and minimal maintenance was already indicating that they would need early replacement. The use of unseasoned timber in their construction had not helped, as this deteriorated rapidly. So there was a huge pent-up demand for new buses. To compound that, the Government was pushing manufacturers of all kinds to build for export, in order to earn the revenue needed to rebuild the economy. So there was no chance that the old-established manufacturers would keep up with demand from the domestic market. The whole situation was further compounded by erratic supplies of raw materials as Britain gradually returned to normality.

With a booming market and an industry that could not meet demand, a multitude of new bus-body manufacturers started up. Many were small engineering companies that had built up most of the necessary skills from wartime work on aircraft. Others were builders of luxury car bodywork, for which there was very little demand in the difficult economy of the late 1940s. Some seem to have specialized in refurbishing existing bodies rather than building new ones; many such rebuilds were done by local firms not otherwise involved in PSV manufacture, while others were carried out in Corporation workshops.

In The British Bus Story – The Fifties, Alan Townsin listed thirty-nine new bus-body makers that had been set up between 1945 and 1950. But demand soon levelled out and by 1952 the market was saturated. Bus operators tended to return to the established makers, whose products they knew they could trust. Tellingly, just two of those companies that had entered the market between 1945 and 1950 were still in business ten years later. The others mostly faded into obscurity in the first half of the decade.

Ready for delivery: a selection of completed vehicles outside the Duple works at Hendon.

Although bus bodies in the immediate post-war period picked up where their counterparts of the late 1930s had left off, there were signs of change. Metal-framed bodies returned and familiarity with aluminium alloys in aircraft construction led to a willingness to experiment with these in bus bodies. There was a trend towards jig-building, again resulting from wartime aircraft practice that had aimed for standardization and ease of repair. There were no major new design trends for double-deckers yet, but single-deck design did begin to change – and very noticeably.

There was a marked swing towards forward entrances on single-deckers rather than the centre or rear entrances of the 1930s. In the interests of ‘modernity’, full-fronts became increasingly popular, often concealing the traditional vertical radiator behind a styled panel, although this was more noticeable on coaches than on service buses, which generally retained half-cab designs. Five-bay construction on double-deckers gradually gave way to four-bay designs. Some coach bodybuilders (mainly the smaller, newer ones) experimented with swoopy, aircraft-inspired styles and shapes as they tried to make their names. Many of these designs, which continued into the early 1950s, were excessive, bizarre, or both.

But the major change for single-deckers was the arrival of underfloor-engined chassis. The real challenges did not begin until AEC (with the Regal IV) and Leyland (with the Royal Tiger) entered the market in 1950, but the arrival of the first underfloor-engined designs from operator Birmingham & Midland Motor Bus Company (BMMO) in 1946 and chassis maker Sentinel in 1948 certainly made the designers of single-deck bodies sit up and think very hard about the way things would go in the future.

THE 1950s

The 1950s was another decade of change and not least among the factors driving that change was the increasing popularity of the private car. Car owners used their vehicles for local journeys and holidays alike, so reducing the need for bus services and coach tours. The railways suffered similarly. Costs became more important to operators than ever before, as they tried to maintain profits in a dwindling market. Bus bodybuilders altered their designs to suit, squeezing more fare-paying seats into the footprint of the newly permitted 30ft (9m) long and 8ft (2.4m) wide chassis that came on to the market. By the end of the 1950s, double-deckers were seating as many as seventy-two passengers and single-deck buses were carrying forty-four or even forty-five, while even coaches typically had forty-one seats.

The full-size vertical-engined chassis lasted only until 1952–3, although the new lightweight Bedford SB chassis still had its engine at the front. The early 1950s saw a flowering of full-front designs and the new SB was always intended to have them. Coach designs in the early 1950s were a direct continuation of shapes pioneered in the 1930s, with curving waistlines and roof contours, and usually sloping window pillars as well. Generally speaking, the smaller concerns were happier working on vertical-engined chassis and many of them failed quite spectacularly to create pleasing designs for the new underfloor-engined types. As the demand for coach travel began to diminish and the bigger manufacturers came up with better designs at keener prices, so the order books of the smaller companies dried up and many of them passed into history. By the mid-1950s, coach bodybuilding was mainly carried out by a handful of the big names: Burlingham, Duple, Harrington and Plaxton. Duple was the most prolific, largely thanks to the special relationship it had developed with Bedford through designs for the SB chassis.

Atkinson, Daimler, Dennis and Guy all followed the lead set by Sentinel, AEC and Leyland, and even Bristol came up with an underfloor-engined chassis, although it was available only to the nationalized British Transport Commission (BTC) operators. This relentless move away from vertical-engined types forced the bodybuilders to come up with new designs very quickly and their indecent haste was evident in some of the results.

Service bus bodies were mostly square-rigged, boxlike and heavy in appearance, with thick window pillars. The need for driver supervision of the entrance resulting from the move towards one-man operation meant that front entrances were almost universal by 1955. These were usually equipped with power-operated folding doors, which demanded a rectangular doorway that in turn contributed to this boxiness. For coaches, Duple and Harrington adapted existing designs for vertical-engined chassis with sometimes disappointing results. Many of the smaller bodybuilders came up with coach designs that were awkward or downright ugly, while others did their best to be imaginative but were often guilty of excess, or at least of style for style’s sake.

Among the early entrants to the market, by far the most successful was the Seagull coach body by Burlingham, so named after the Blackpool operator for whom the first example was built. It became a design classic of its time. Designs of major importance from the later 1950s were the Plaxton Panorama, which featured the large windows its name suggested, and the Harrington Cavalier, which combined front and rear body peaks with a curved-glass windscreen made possible by new rules permitting fixed screens and new toughened glass technology delivering three-dimensional curves. The earliest underfloor-engined coaches mostly had centre entrances, but by the end of the decade front entrances were the norm.

Double-deck bodies in the first half of the 1950s evolved mainly to meet demands for lighter weight and higher seating capacities. Metal-framed construction was universal. Only the strong survived: Leyland closed its body department in 1954 and Crossley became an outstation of Park Royal after the company had been absorbed by the ACV group. Companies such as Brush, Cravens and Roberts were among the casualties. The need to reduce costs led to a period of rather austere designs at the end of the decade, coinciding with the arrival of the pioneer rear-engined chassis, the Leyland Atlantean. It would be the mid-1960s before really attractive designs were available for that chassis and its imitators, as all the first ones were adapted from existing designs for frontengined chassis.

THE 1960s

Compared to earlier times, only a handful of British bodybuilders remained active in the 1960s. Their numbers thinned out as the decade wore on, too: Burlingham and Willowbrook, for example, were engulfed by Duple. At the end of the decade, the fully standardized Leyland National bus arrived, and several older chassis from the Leyland group of companies disappeared. Without those chassis on which to work, the independent bodybuilders saw their custom disappearing fast.

Nevertheless, the 1960s were notable for some formidably attractive new coach designs. The spread of the motorways and of the express coach services that used them, plus the contraction of the railways network, added up to a demand for designs that were as good-looking as they were functional. The increasing use of glass-reinforced plastic (GRP) mouldings allowed designers to experiment with some interesting designs that would have been too complex, too expensive, or both, if made of traditional metal. Meanwhile, the newly permitted 36ft (11m) maximum length demanded different designs to achieve a harmonious balance of line; permitted width also increased by 2½in (64mm) to 8ft 2½in (2.5m).

On the service bus front, however, the standardization represented by the Leyland National was in many ways a watchword of the times. Variety was no longer seen as the spice of life. As they had been doing for many years, the BET (British Electric Traction) companies developed their own standard single-deck service bus style in the early years of the decade. This had modern-looking wrap-around front and rear screens and the bodybuilders who wanted BET orders had to build to this standardized design or lose the contract.

There was similar pressure from operators in other ways. A desperate need for attractive designs on the new rear-engined double-deck chassis led several municipalities to take matters into their own hands. Bolton, Liverpool, Manchester and Oldham all drew up the designs they wanted. It was then down to the bodybuilders they approached to put them into production. From 1968, Park Royal and Roe had a new standard body design for the Leyland Atlantean and Daimler Fleetline chassis that then dominated the market, and the same design, with some modifications, was subsequently made by Metro-Cammell, Northern Counties and Willowbrook as well.

This scene from Shorts’ factory shows how upper and lower decks were assembled separately before being fitted together. An upper deck is being transported across the body assembly shop by overhead crane.

These pictures show the jig-built metal frames of Leyland bodies from the 1930s. Wood was used only for the floors and as a medium for securing panels and brackets.

Anxious to maintain market share and to deliver a standardized design, Metro-Cammell moved into integral construction in 1969, buying in mechanical units from Scania in Sweden. Although the original Metro-Scania was less successful than its makers had hoped, it was important in showing the way forwards for bus construction in Britain.

Then, just as the 1960s were drawing to a close, more new legislation was introduced to affect the design of coaches. This was a relaxation of the maximum permitted length from 36ft (11m) to 39.4ft (12m). Operators and bodybuilders alike were slow to take advantage of the new regulations, which were announced in 1967 but took effect from 1968. Their main impact would be on the designs of the 1970s.

THE 1970s

The gradual shrinkage of the PSV market in Britain during the 1960s had taken its toll among the smaller builders of bus and coach bodywork, and even some of the bigger ones had huddled together for comfort. There was no future in increasing prices to compensate for lower sales volumes, because operators were being ever more tightly squeezed by social changes that did not favour public transport. Continuing the trend of the 1960s, more and more homes now owned a car, and more and more families stayed indoors to watch television in the evenings instead of going out and travelling to cinemas, theatres and other places of entertainment.

All this left the market ripe for continental European bus builders to move in. With their larger markets and consequently higher sales volumes, they could keep costs lower and compete very effectively with British products on their home ground. So it was that some British coach dealers – Moseley was the first – began to offer vehicles bodied by continental European coach-builders. From 1968 Caetano bodies from Portugal had been available under the Moseley Continental brand; though unfashionably rectangular in appearance, with garish grilles for decoration, they soon made their mark. By 1970, Caetano was an important player on the British coach market. Moseley looked into the possibilities of selling Van Hool coachwork from Belgium in 1969, but it was Arlington that eventually handled these bodies, which were available for both lightweight and heavyweight chassis as the 1970s got under way. Before the decade was out, there were others: Berkhof (from the Netherlands), Beulas (from Spain), Ikarus (from Hungary), Irizar (from Spain) and Jonckheere (from Belgium).

The 1970s also saw a greater willingness by operators to accept integral construction, not least because many of the products coming in from the European continent depended upon it. That it reduced flexibility in body design was no longer an issue; what mattered was whether the end result was affordable, while also being sufficiently attractive and comfortable to earn customer approval.

The need to deal with lower passenger numbers generally also led to the rise of a new type of bus in the early 1970s. While minibuses gradually gained in popularity for stage-carriage services, the midibus became popular where more room was needed. Based on underfloorengined PSV chassis, these more or less matched such vehicles as the Bedford OB of the 1940s in size, but the real problem for bus bodybuilders was getting the proportions right. Too many looked like truncated toy editions of their full-size brethren.