12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

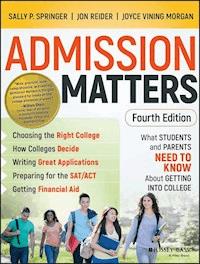

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

Make sense of college admissions and prepare a successful application Admission Matters offers comprehensive, expert, and practical advice for parents and students to guide them through the college admissions process. From building a college list, to understanding standardized tests, to obtaining financial aid, to crafting personal statements, to making a final decision, this book guides you every step of the way with clear, sensible advice and practical tips. This new fourth edition has been completely updated to reflect the latest changes in college admissions. including new developments in standardized testing, applications, financial aid and more. Questionnaires, interactive forms, checklists, and other tools help you stay focused and organized throughout the process.. With the answers you need and a down-to-earth perspective, this book provides an invaluable resource for stressed-out students and parents everywhere. Applying to college can be competitive and complex. Admission Matters offers real-world expert advice for all students, whether you're aiming an Ivy or the state school close to home. It also includes much needed guidance for students with special circumstances, including students with disabilities, international students, and transfer students. In addition, athletes, artists and performers, and homeschoolers will find valuable guidance as they plan for and apply to college. * Understand how the admissions process works and what you can and cannot control * Learn how to build a strong list of good-fit colleges * Craft a strong application package with a compelling personal statement * Get expert advice on early admissions, financial aid, standardized testing, and much more * Make a final decision that is the right one for you Whether you think you've got applying to college under control or don't even know where to begin, Admission Matters is your expert guide throughout the college admissions process.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 707

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Part 1: What You Need to Know Before You Begin

Chapter 1: Why Has College Admissions Become So Competitive?

It Used to Be Simple . . . but Not Anymore

What Is Selectivity All About?

Why Is There So Much Interest in a Small Group of Colleges?

The Rankings Game

Why Are Rankings So Popular?

Admissions Rate and Yield and How They Contribute to College Frenzy

“I'll Make More Money If I Graduate from an Elite College”: A Myth

The Importance of Fit

Notes

Chapter 2: What Do Colleges Look for in an Applicant?

How College Admissions Has Changed

What Matters Now

The Academic Record

Standardized Tests

Engagement Beyond the Classroom

Personal Qualities: The Person Behind the Paper

Hooks and How They Help

Fitting It All Together

Notes

Chapter 3: How Do Colleges Make Their Decisions?

Who Works in Admissions?

What Happens to Your Application?

Tentative Decisions

How The Final Decision is Made

A Look Inside the UCLA Admissions Process

The Special Case of the Most Selective Colleges

The Role of Your High School Counselor

How College Access Programs Can Help

Should You Consider Hiring an Independent College Counselor?

The Parents' Role

Notes

Chapter 4: How Colleges (and Students) Differ: Finding What Fits

So Many Choices: How Do You Begin?

Some Questions to Ask Yourself

Community Colleges

Liberal Arts Colleges

Research Universities

What's in a Name?

Master's Universities and Baccalaureate Colleges

Specialized Programs

Colleges with Special Affiliations

Earning Your Degree Abroad, in English

Which Kind of College Is Best for You?

Majors, Careers, and Curriculum

How Easily Can You Get Advice and Help?

Determining Your Priorities

Notes

Part 2: Making the Right Choices for You

Chapter 5: Where Should You Apply?

Start at Your Counseling Office

Use A College Search Tool

Meeting College Representatives

Read What They Send You (but Don't Let It Go to Your Head)

How to Narrow Things Down

The College Visit

Selectivity and Your College List

Check out the Data

How Long Should Your College List Be?

The Key to a Good College List

A Word About Finances

Notes

Chapter 6: The Big Tests

What Are the SAT and ACT?

The Structure of the SAT and ACT

Content Tested by the SAT and ACT

Pacing of the SAT and ACT

How Are the Tests Scored?

How Much Do Standardized Tests Count?

How Do the PSAT and PreACT Fit into the Picture?

Which Test Should You Take?

How Important Is the Essay?

How Does Test Prep Work?

When Should You Test?

The National Merit Scholarship Competition

The Case of Special Accommodations

The SAT Subject Tests

Test‐Optional Schools

A Word to Parents About Standardized Tests

Notes

Chapter 7: Deciding About Early Decision and Other Early Options

An Overview of Early Acceptance Programs

The Pros and Cons of Early Decision

Early Action in Detail

Should You Apply Early Decision or Early Action?

Likely Letters and Early Notification

The Advantage of Thinking Early Even If You Decide Against Applying Early

Notes

Chapter 8: Paying the Bill

Key Concepts for Understanding Financial Aid

How Colleges Determine Your Financial Need

What Forms Will You Have to File?

Getting an Estimate of Your Financial Need

What Goes into a Financial Aid Package?

Why Need‐Based Packages Can Differ from College to College

Will Your Need for Financial Aid Affect Your Chances for Admission?

How Merit Aid Works

Financial Aid for Veterans and Their Families

Other Scholarship Sources

Financial Aid and Your College List

Evaluating Aid After You've Been Accepted

Another Word About Early Decision

Planning Ahead When Your Child Is Young

Notes

Part 3: Tackling Your Applications

Chapter 9: Applying Well, Part I: The Application and the Essay

Getting Off to A Good Start

Application Choices

Writing an Effective Personal Essay

An Important To‐Do List

Notes

Chapter 10: Applying Well, Part II: Advice to Parents and Students

Getting Great Letters of Recommendation

Shining in Your Interview

Showing That You Are Interested

Highlighting What You've Accomplished

The Canadian, British, Irish, and Dutch Difference

You've Finished Your Applications—What's Next?

Notes

Chapter 11: Making the Most of Your Special Talents

The Student Athlete and Athletic Recruitment

Options for the Student Artist

Notes

Chapter 12: Students with Special Circumstances

Students with Disabilities

Tips for Homeschoolers

Making a Change: How to Successfully Transfer Colleges

Notes

Chapter 13: Advice for International Students

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Being an International Applicant

What Are Colleges Looking For?

How Will Your Application Be Reviewed?

Where Should You Apply?

The Role of Standardized Tests

Tests to Show Proficiency in English

Getting the Application Completed

Paying for Your Education

Special Circumstances

The Bigger Picture

Notes

Part 4: Bringing the Process to a Close

Chapter 14: Making

Your

Decision After the Colleges Make Theirs

How Will You Be Notified?

The Special Case of Early Decision

What You Can Do If You Are Deferred

When It Is Your Turn to Decide in the Spring

Dealing With Disappointment

Spring Admits

Taking Another Look

Revisiting Financial Aid

How Wait Lists Work

Deposit Ethics

Should You Consider a Gap Year?

A Word About Senioritis

Celebrate and Enjoy!

Notes

Chapter 15: What Matters Most

Some Parting Thoughts for Parents

Some Parting Thoughts for Students

Appendix A: College Research Worksheet

Appendix B: Essay Prompts, 2017–2018

Common Application

Universal Application

Coalition Application

Cappex Application

Appendix C: Financial Aid Shopping Sheet

Appendix D: Cost of Attendance Worksheet

College Preparation Time Line

Freshman Year

Sophomore Year

Junior Year

Senior Year

What if you are Beginning Your Search in Senior Year?

Resources

General Admissions Information

Reference Guides to Colleges

Narrative and Evaluative Guides to Colleges

Special Focus Guides

Test Preparation

Essay Writing

Advice for Artists

Advice for Athletes

Special Circumstances

Financial Aid

International Students

Gap Year

Studying in Canada, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Holland

About the Authors

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

v

vi

i

ii

iii

ix

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

197

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

347

348

349

351

352

353

354

355

357

358

359

360

361

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

PRAISE FOR Admission Matters What Students and Parents Need to Know About Getting into College

Fourth Edition:

“If you are looking for a book where you can get the best possible advice from authors who have the ability to anticipate and answer your questions with a marvelous combination of experience and insight, then this is the book you need to buy . . . quickly!”

Gary L. Ross, vice president and dean of admission, Colgate University

“Written by deeply experienced and respected professionals, Admission Matters aims to ‘empower students and their families to make good choices . . . and retain their balance and sanity at the same time.’ Bullseye!”

Philip Ballinger, associate vice provost for enrollment and undergraduate admissions, University of Washington

“You can't ask for a better introduction into college admissions. From exploring colleges, to applying, and deciding, Admission Matters continues to be an essential, comprehensive book for high school students and families.”

Art D. Rodriguez, dean of admission and financial aid, Vassar College

“Admission Matters demystifies college admissions like no other book has, with the most current information on testing, paying for college, and finding the right college.”

Robert Massa, senior vice president for enrollment and institutional planning, Drew University, and former vice president, Dickinson College and dean of enrollment, Johns Hopkins University

“I absolutely love this book and highly recommend it as a must‐read resource for students and parents going through the college admission search and application process. It's easy to understand, current, and contains spot on advice.”

Bob Bardwell, school counselor and director of school counseling, Monson High School (MA)

“A thoughtful, thorough tour of the college selection process. Admission Matters goes well beyond the basics, and invites the student to personalize the college process as few books do.”

Patrick O'Connor, associate dean, college counseling, Cranbrook Kingswood Upper School (MI)

“Clear, comprehensive, and sane advice from trusted experts. This updated guide provides a road map to what is often a bewildering and anxious process for students and families.”

Debra Shaver, dean of admission, Smith College

“Comprehensive, insightful, based on current research and insider expertise. A straightforward guide to today's complex college admission process that is anything but straightforward.”

Bruce Reed, co‐founder, Compass Education Group

“I wish I had this book when my daughters were applying to college. Admission Matters somehow finds clarity amidst the complicated set of confusing, even contradictory college admission practices.”

Kirk Brennan, director of undergraduate admission, University of Southern California

“An enormously useful and easy‐to‐read guide to getting into college. While others may claim to be the ‘gold standard,’ this one is the real deal.”

Nancy Griesemer, independent educational consultant and long‐time blogger on colleges and the admissions process

“All readers of Admission Matters—whether students, parents, or counselors—will benefit from the deep insights and expertise of the authors. Accessible and a good read, the book provides much needed guidance for the college admissions process.”

Sam Carpenter, senior assistant director of admissions, Duke University

“This book is a ‘must read’ for all families going through the college admissions process. If you are looking for a guide to help you approach the college search in a meaningful way, this is the book for you.”

Angel Perez, vice president for enrollment and student success, Trinity College

“Admission Matters provides a straightforward, no nonsense blueprint to navigate the complex college admissions process.”

Jon Westover, senior associate director of undergraduate admissions, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

“As an experienced counselor and the parent of a high school junior, I found this book packed with so many helpful and informative ideas to share with both my students and my own children. A must‐have for every college‐bound student's household.”

Kathi Moody, school counselor, Lynnfield High School (MA)

“This brand new edition of Admission Matters is just what the doctor ordered. It is filled with wise, up‐to‐date information and insider knowledge. Families will love it.”

Marjorie Hansen Shaevitz, author and founder, adMISSIONPOSSIBLE

“This is a must‐have resource for students and families navigating the college admissions process. The authors are respected, long‐time professionals and get it right from the search to enrollment.”

Jeff Rickey, vice president and dean, admissions and financial aid, St. Lawrence University

“Admission Matters is current, insightful, non‐dogmatic and the most inclusive book about the complex U.S. college admission process I have read. I can even see using it as a training manual for my new staff on the complexity of U.S. college admission; it is that thorough and in‐depth.”

Paul Thiboutot, vice president and dean of admissions and financial aid, Carleton College

“Admission Matters is the quintessential book for anyone who wants to thoroughly understand today's college landscape. It is a must read.”

Nanette Tarbouni, director of college counseling, John Burroughs School (MO)

“This is a valuable resource, with encyclopedic information on nearly every aspect of college admission. Whether you are new to college searches or a seasoned professional, you will find answers to detailed questions as well as a rich overview of this ever‐changing and complex process.”

Ralph Figueroa, dean of college guidance, Albuquerque Academy (NM)

“Filled with both common sense and sage advice, the fourth edition of Admission Matters is the only guide any high school student—and his or her parent—will ever need.”

Jennifer Delahunty, former dean of admissions and financial aid, Kenyon College

“This updated edition is a great addition to the library of any family with college‐bound students or any counselor's library.”

William S. Dingledine Jr., certified educational planner, past president Southern Association for College Admission Counseling

“Admission Matters is the single best comprehensive guide available to help students and their families avoid the harmful aspects of the ‘admission marketplace.’ The new edition continues that noble tradition by providing essential information and tools to make the college admission process sane, humane, and perhaps even, for its fortunate readers, a great voyage of personal growth and discovery.”

Michael Beseda, vice provost for strategic enrollment management, University of San Francisco

ADMISSION MATTERS

What Students and Parents Need to Know About Getting into College

FOURTH EDITION

Sally P. Springer

Jon Reider

Joyce Vining Morgan

Copyright © 2017 by Sally P. Springer, Jon Reider, and Joyce Vining Morgan. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-BassA Wiley BrandOne Montgomery Street, Suite 1000, San Francisco, CA 94104-4594—www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is Available

ISBN 9781119328391 (Paper)ISBN 9781119329909 (ePDF)ISBN 9781119329893 (ePUB)

Cover design: WileyCover image: © FatCamera/Getty Images, Inc.

FOURTH EDITION

To our children

Acknowledgments

Many colleagues have shared our goal of improving the college admissions process for students and parents and have helped us, in ways large and small, in the writing of the fourth edition of Admission Matters. We are grateful to all of them: Jed Applerouth, Terry Axe, Carolyn Barr, Bonnie Burks Becker, Jeffrey Corton, Jeffrey Durso‐Finley, Frances Fee, Duffy Grant, Vicki Kleinman, Douglas Long, Marybeth Kravets, Nancy Hargrave Meislahn, Bruce Poch, John H. Provost Jr., John Raftrey, Bruce Reed, Zita Riedlová, Gary Ross, Pam Schachter, Beatrice Schultz, Catherine Sinclair, Leanne Stillman, Ken Suratt, Marilyn van Loben Sels, Sue Wilbur, and Kim Zwitserloot.

We are indebted as well to the Jossey‐Bass editorial team for the fourth edition—Kate Bradford, senior editor; Connor O'Brien, project editor; and Sharmila Boominathan, production editor—for guiding us so capably through the publication process.

Three people who have made lasting contributions to Admission Matters through all four editions deserve special acknowledgment and recognition. The insights and wisdom of Marian Franck, coauthor of the first edition, remain an integral part of the book. Lesley Iura, then education editor at Jossey‐Bass, saw the value and potential of Admission Matters when it first arrived on her desk more than 13 years ago. Later, as publisher at Jossey‐Bass, she continued to support Admission Matters as a valued part of the Jossey‐Bass list. Professor emeritus Håkon Hope has contributed encouragement, insights, and support from the earliest stages of planning for the first edition through the final stages of reviewing page proofs for the fourth edition. His dedication to his students and their academic and personal development has been an inspiration throughout.

Finally, we want to thank the thousands of high school and college students whose lives we have touched over the course of our careers, both in the classroom and as counselors. Their dreams and aspirations have encouraged us to try to ease the path for others yet to undertake the college admissions journey.

Introduction

It is easy to understand why the college admissions process has become such a challenge, and even an ordeal, for many students and their families. Everywhere they look, families are barraged by evidence of “college mania.” Online and print media regularly regale readers with horror stories about the competition involved in gaining admission to selective colleges as application numbers rise and admissions rates fall, sometimes dramatically in a given year. Classmates, neighbors, coworkers, and even virtual strangers are all too eager to share tales about terrific kids with great academic and extracurricular records who were denied admission by the colleges of their choice.

As likelihood of admission becomes harder to predict at many schools, students find themselves applying to an increasing number of colleges to protect themselves. Of course, one major consequence of such behavior is an overall increase in application numbers and corresponding declines in admissions rates at those schools, feeding the very problem students are hoping to address by submitting more applications.

Adding to the challenge is the continuing rise in the cost of college, with the sticker price at some private four‐year colleges now approaching $70,000 per year. Recent changes in the standardized testing policies of many schools, as well as changes in the tests themselves, have also contributed to the uncertainty surrounding college admission.

The result of all of this is that families often find themselves caught up in a high‐stakes competition in which they are uncertain about the rules and even more uncertain about the outcome. Parents feel uncomfortable trying to support their children in a process that they do not completely understand and are not sure they can afford. Even those who consider themselves knowledgeable may quickly find that much of what they know is out‐of‐date or based on unverifiable hearsay.

Frank Bruni, author of a widely acclaimed book entitled Where You Go Is Not Who You'll Be: An Antidote to the College Admissions Mania, dedicated his book as follows: “To all the high school kids in this country who are dreading the crossroads of college admissions and to all the young adults who felt ravaged by it. We owe you and the whole country a better, more constructive way.”1 We fully agree.

College admissions does not have to be, and should not be, an ordeal. A clear understanding of the process can empower students and their families to make good choices for themselves and allow them to retain their balance and sanity at the same time. That has always been the goal of Admission Matters, from its first edition in 2005 through this fourth edition today.

We have written this book to demystify the college admissions process by explaining how it works and to level the playing field for those without access to extensive assistance from knowledgeable high school counselors or sometimes any counselors at all. It will also help those who have access to good counseling but would still like some extra support. Our advice is designed for students planning to apply to any four‐year college, whether highly selective or not.

Admission Matters explains

How rankings motivated by profits contribute to the application frenzy

How the admissions process really works, and what you can, and cannot, control

The ways in which colleges differ that really matter

How you can build a list of colleges that are a good fit for you and submit strong, competitive applications to gain admission to them

How and why many colleges use standardized tests and how you can best prepare for them

What recent changes in standardized tests as well as testing policies at many schools mean for you

When an early application makes sense, when it can be a mistake, and how to tell the difference

How financial aid works, what you can expect from it, and how you can increase your chances of receiving more

How to prepare strong applications that can help you distinguish yourself from other applicants

What you—student and parent—can do to work together in appropriate and respectful ways throughout the admissions process to achieve a happy outcome

And much more. In this thoroughly revised fourth edition of Admission Matters, we have worked hard to address the many changes that have occurred in the world of college admissions since our last edition. We want you, our student and parent readers, to begin the college admissions journey confidently with the latest and most complete information available. As before, students with disabilities, international students, and transfer students will find much needed guidance to address their special circumstances, as will athletes, artists, and homeschoolers. Information for first‐generation college students and undocumented students is included as well. We want Admission Matters to continue to be the most up‐to‐date, clear, insightful, supportive, and practical book on college admissions anywhere.

We recognize, however, that you may want more information on certain topics than space allows us to include. To help you access that additional information easily, we have provided a list of resources, many of them on the web, that give detailed information on topics such as financial aid and athletic recruiting to supplement our own coverage. To keep Admission Matters as up‐to‐date as possible, we are maintaining a website with free updates and additional materials. You can find it at www.admissionmatters.com. We welcome your feedback.

We feel we are especially well qualified to be your guides. Among the three of us, we have more than 100 years of experience in secondary and higher education in the roles of high school teacher and college counselor, college admissions officer, college professor and administrator, and independent educational consultant. Collectively we have worked with thousands of students across the United States and abroad. We are also proud parents of successful college graduates, so we have experienced the admissions process firsthand from the parent perspective as well. We are delighted that our readers in the general public have found Admission Matters enjoyable and easy to read, and we are honored that professional colleagues use it widely as a text in courses on college admissions for those studying to be counselors themselves.

We hope Admission Matters will serve as your trusted road map through the college admissions journey.

PART 1What You Need to Know Before You Begin

Chapter 1

Why Has College Admissions Become So Competitive?

Chapter 2

What Do Colleges Look for in an Applicant?

Chapter 3

How Do Colleges Make Their Decisions?

Chapter 4

How Colleges (and Students) Differ: Finding What Fits

CHAPTER 1Why Has College Admissions Become So Competitive?

For members of the baby boom generation born between 1946 and 1964, applying to college was a pretty simple process. Those bound for a four‐year college usually planned to go to a school in their home state or one fairly close by; many considered a college even 300 miles from home to be far away. Few students felt the need to apply to more than two or three colleges, and many applied to just one. They chose their colleges based on location, program offerings, cost, and difficulty of admission, with a parental alma mater sometimes thrown in for good measure. For the most part, the whole process was fairly low key. If students did their homework carefully before deciding where to apply, the outcome was usually predictable. Of course, there were surprises—some pleasant and some disappointing—but nothing that would raise the issue of college as to the level of a national obsession.

IT USED TO BE SIMPLE . . . BUT NOT ANYMORE

Fast‐forward 50 to 60 years when headlines tell a very different story for students applying to college now: “Why Is College Admissions Such a Mess,”1 “Applied to Stanford or Harvard? You Probably Didn't Get In. Admit Rates Drop, Again,”2 “New SAT Brings New Challenges, Same Old Pressure,”3 “Best, Brightest and Rejected: Elite Colleges Turn Away up to 95%,”4 “How College Admissions Has Turned into Something Akin to ‘The Hunger Games,' ”5 “Why Colleges Aggressively Recruit Applicants Just to Turn Them Down,”6 and “The Absurdity of College Admissions.”7

Colleges themselves make equally jarring announcements. In spring 2003, Harvard announced that for the first time it had accepted just under 10 percent of the students who applied for freshman admission for the class of 2007, or about 2,000 out of 21,000 applicants. This was a new low not only for Harvard but also for colleges nationwide. But much more was to come. By spring 2016, the admissions rate at Harvard had fallen to 5.2 percent out of an applicant pool of over 39,000 for the class of 2020, and at least nine other colleges had joined Harvard in the “under 10 percent” club. Among them was the University of Chicago, reporting an admissions rate of less than 9 percent for the class of 2020, down from a little less than 16 percent five years earlier and just over 38 percent a decade before.

Many public universities, particularly state flagship campuses, have also experienced dramatic growth in applications as well as falling admission rates. For example, UC Berkeley received 82,000 applications for the freshman class of 2020 and admitted 17.5 percent. Ten years prior, the campus received fewer than 42,000 applications and admitted 23.8 percent.

These are just a few of the many colleges reporting record‐breaking numbers of applications and record‐low rates of admission, continuing a trend that began two decades earlier. What has happened to change the college admissions picture so dramatically in such a relatively short time?

Population Growth

The simple explanation seems to be supply and demand: more high school graduates than ever are now competing for seats in the freshman class. After declining somewhat in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the number of students graduating from high school in the United States has risen steadily. In 1997 there were 2.6 million graduates; by 2013, the number had grown to almost 3.5 million. Although the numbers are now declining slightly, they are projected to stay at or above 3.4 million until 2028.8

I don't think anyone is complacent about getting a high‐quality applicant pool.

Harvard University admissions officer

Social Changes

But it turns out that the increase in applications is not just because of population growth. Application numbers have risen much faster than the age cohort because of important social changes. Not only are more students graduating from high school each year but also a greater percentage of them are interested in going to college. Studies confirm that a college diploma increases lifetime earnings, and many desirable careers require education beyond the bachelor's degree. As a result, more students are seeking to attend four‐year colleges, including students from underrepresented minority groups who previously attended college at much lower rates.

At the same time, colleges themselves have increased their efforts to attract large, diverse pools of applicants. Many have mounted aggressive programs to spread the word about their offerings nationally and internationally. Through colorful brochures mailed directly to students, e‐mail blitzes and social media activity, visits to high schools by admissions officers, college nights at local hotels, and information booths at college fairs, colleges are reaching out to prospective freshmen in the United States and abroad with unprecedented energy and at great expense.

Sophisticated marketing techniques are used not only by colleges that may have problems filling their freshman class but also by colleges with an overabundance of qualified applicants. And it works! As a result, more and more college‐bound students have become aware of and are willing to seriously consider colleges far away from home. Rising standards of living across the globe are also contributing to the number of students from abroad, particularly Asia, choosing to study in the United States.

The Role of the Internet

In addition, the Internet has played a major role in how students approach college admissions. Although printed material and in‐person presentations still help students learn about different colleges, the web has become the primary source of information for students. Students can visit campuses through sophisticated online virtual tours and videos and find answers to many of their questions from college Facebook pages, FAQs posted on their websites, and by tracking college‐sponsored blogs and Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat feeds. Colleges have invested heavily in technology to showcase themselves.

The Internet has also made it easier than ever to apply to college. Applications can be completed and submitted online, saving a lot of the time and effort that traditional paper applications once required. Simplifying things even more, more than 700 colleges now accept the Common Application, a standardized application in which a student can put in his or her basic information just once and then submit it online to up to 20 of those colleges.

With admission harder to predict, students are now submitting more applications than ever before. Ten to 12 applications are now the norm at many private schools and high‐performing public high schools; 15 or more applications are not uncommon. Through technology students can apply to an ever‐larger number of colleges.

All of these factors taken together—growth in the population of 18 year olds, greater interest in college, sophisticated marketing efforts, ready access to information, and ease of applying made possible by the Internet—explain why it is harder to get into college now than ever before.

But even that is not the whole answer.

As word spreads about the competition for college admission, students respond by applying to even more colleges to increase their chances of acceptance. In so doing, they end up unwittingly contributing to the very problem they are trying to solve for themselves.

High school counselor concerned about the trend

Where the Real Crunch Lies

Many people are quite surprised to learn that with relatively few exceptions, most four‐year colleges in the United States still accept well over half of their applicants. In fact, each May, the National Association for College Admission Counseling posts on its website a list of hundreds of colleges still seeking applicants for the fall. Many of these have vacancies well into the summer. How can this fact be reconciled with the newspaper headlines (not to mention firsthand reports from students and parents) about a crisis of hyper‐selectivity in college admissions?

It turns out that the real crunch in admissions—the crunch that drives the newspaper headlines and the anxiety that afflicts many families at college application time—applies to only about 150 of the most selective colleges that attract applicants from all over the country and the world. What's wrong with all the rest? Nothing, of course, except that they aren't in that list of 150. Bill Mayher, a college advisor, summarizes the problem succinctly: “It's hard for kids to get into colleges because they only want to get into colleges that are hard to get into.”9

WHAT IS SELECTIVITY ALL ABOUT?

The percentage of students offered admission to a college is a major factor in determining its selectivity. As the number of applications to a college increases, its admissions rate decreases. Another key factor affecting selectivity is the academic strength of the applicant pool because strong applicants tend to self‐select when applying to certain colleges, especially some smaller ones, well‐known for their academic rigor. Both of these factors—admissions rate and strength of the applicant pool—help determine the selectivity of a particular school. Complicating matters even more is that some schools have different admissions processes for different programs, with some programs, such as engineering or business, more selective than others within the same school.

Our Definition of Selectivity

To simplify our discussion here, we define selectivity only in terms of admissions rate and define a selective college as one with an overall admissions rate of less than 50 percent. We further divide selective colleges into four categories: ultra‐selective colleges (those admitting less than 10 percent of their applicants), super‐selective colleges (those admitting less than 20 percent of their applicants), highly selective colleges (those admitting less than 35 percent of applicants), and very selective colleges (those admitting less than 50 percent of applicants). In the following box we include colleges that offer a broad array of programs and not those that have a highly specialized mission such as military academies, conservatories, or those offering instruction in only one academic area such as business. We will discuss these specialized programs further on in Admission Matters, but for now we are not including them in the data presented here.

production: please format this sidebar as it appears on pp. 6–7 of 3rd edition

Colleges by Admissions Rate for the Class of 2020

Ultra‐selective (less than 10 percent of applicants admitted)

Brown University

Caltech

University of Chicago

Claremont McKenna College

Columbia University

Harvard University

MIT

University of Pennsylvania

Pomona College

Princeton University

Stanford University

Yale University

Super‐selective (less than 20 percent of applicants admitted)

Amherst College

Barnard College

University of California, Berkeley

Bowdoin College

Colby College

Colorado College

Cornell University

Dartmouth College

Duke University

Georgetown University

Grinnell College

Harvey Mudd College

Johns Hopkins University

University of California, Los Angeles

Middlebury College

Northwestern University

University of Notre Dame

Pitzer College

Rice University

University of Southern California

Swarthmore College

Tufts University

Vanderbilt University

Washington University, St. Louis

Wesleyan University

Williams College

Highly Selective (less than 35 percent of applicants admitted)

American University

Bard College

Bates College

Boston College

Boston University

Bucknell College

Carleton College

Carnegie Mellon University

Colgate University

Davidson College

Emory University

Franklin and Marshall College

Georgia Tech

Hamilton College

Haverford College

Kenyon College

Lafayette College

Lehigh University

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

New York University

University of North Carolina

Northeastern University

Oberlin College

Reed College

University of Richmond

Scripps College

Skidmore College

Trinity College (Connecticut)

Tulane University

University of Rochester

Vassar College

University of Virginia

Wake Forest University

Washington and Lee College

Wellesley College

Very Selective Colleges (less than 50 percent of applicants admitted)

Baylor University

Binghamton University

Brandeis University

Bryn Mawr College

Case Western Reserve University

University of Connecticut

Connecticut College

University of California, Davis

Denison University

Dickinson College

University of Florida

Fordham University

George Washington University

Gettysburg College

College of the Holy Cross

University of California, Irvine

University of LaVerne

Macalester College

University of Maryland

University of Miami

University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Muhlenberg College

North Carolina State University, Raleigh

Occidental College

Ohio State University

Pepperdine University

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

St. Lawrence University

University of California, San Diego

University of California, Santa Barbara

Sarah Lawrence College

Smith College

University of South Florida

Southern Methodist University

Southwestern University

Spelman College

Stony Brook University

Syracuse University

Texas Christian University

Trinity University

University of Tulsa

Union College

Villanova University

Washington and Jefferson College

College of William and Mary

University of Wisconsin, Madison

Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Note: This list is not all‐inclusive and omits schools with a highly specialized focus.

Our selectivity classifications are arbitrary, of course, and they don't consider the self‐selection factor we previously noted. Nevertheless, they provide a general idea of the relative difficulty of gaining admission to various schools. Although over 2,000 nonprofit four‐year institutions of higher education in the United States admit 50 percent or more of their applicants (and many admit at least 75 percent), many students focus their attention on the colleges that fall into the four groups we have just defined as selective.

The students applying to these colleges (and especially those in the super‐selective and ultra‐selective tiers) are the ones experiencing the “crisis” in college admissions. The crisis does not affect those applying to community colleges or seeking admission to the many colleges that accept most or all of their applicants. Nevertheless, it is very real to those who are applying to selective colleges in the next few years. You (or your child) may be one of them. In fact, that may be why you are reading this book. We will help you understand all aspects of the college admissions process, build a college list that is right for you, and submit strong applications.

But you don't have to plan to apply to schools we define as selective for this book to be valuable reading. If you'll be applying to some of the many schools that admit at least half of their applicants, this book will help you, too. All students need to understand the admissions process, and all face the challenges of identifying colleges that will be a good fit and then submitting strong applications. We wrote Admission Matters to help all students take the college admissions journey successfully.

WHY IS THERE SO MUCH INTEREST IN A SMALL GROUP OF COLLEGES?

What is behind the intense interest in the small group of colleges and universities that is driving the headlines about a crisis in college admissions, and, in particular, why is there a mystique surrounding the colleges in the Ivy League and a few others accorded similar status? Just what benefits do these elite colleges bestow (or do people believe they bestow) on their graduates?

Prestige, of course, is one obvious answer. The more selective a college, the more difficult it is to get into and usually the greater the prestige associated with being admitted. The student enjoys the prestige directly, and parents do so also by association. Parents are often the primary driver of the push toward prestige, but students also report similar pressures from peers in high school. And, of course, some students seek prestige themselves. Over the last generation, going to a highly ranked college has become a status symbol of greater value than almost any other consumer good, in part because, unlike an expensive car, it cannot simply be purchased if you have enough money.

Although some people openly acknowledge considering prestige in college choice, many more cite the assumed quality of the educational experience as the basis for their interest in an elite college. But this rationale often depends on the unstated and untested assumption that a good indicator of the quality of something is how much others seek it. People assume that selective colleges offer a better education: the more selective, the higher the quality. But is this really true?

Lots of times it's kids, I think, trying to define themselves by their school choice, not so much choosing the school that's right for them, but trying to look good through it. I'm not sure if they get it from parents or from other kids or from teachers. But they get it from somewhere.

Volunteer in counseling office at private high school

Take the eight colleges in the Ivy League, for example: Brown University, Columbia University, Cornell University, Dartmouth College, Harvard University, Princeton University, University of Pennsylvania, and Yale University. One counselor we know refers to them as the “climbing vine” schools to take away some of the glamour attached to the common brand. The Ivy League originally referred only to a football league. (At first, only seven colleges belonged. Brown eventually joined as the eighth member, although several other colleges were considered possibilities at the time.)

Over time, though, the term Ivy League became synonymous with prestige and a very strong academic reputation rather than an athletic league. The admissions rate of each Ivy places it in the ultra‐selective or super‐selective category. Certainly, each has fine students and faculty members renowned for their research. Everyone agrees that they are excellent schools, but do the Ivies automatically offer undergraduates a better educational experience than many other institutions? The answer, commonplace to those in academic circles but surprising to much of the public, is assuredly no.

Harvard is perhaps the most overrated institution of higher learning in America. This is not to imply that Harvard isn't a good school—on the contrary, Harvard is an excellent school. But its reputation creates an unattainable standard; no school could ever be as good as most people think Harvard is.

Comment by a Harvard student

THE RANKINGS GAME

A major contributor to the mystique of selective colleges has been the annual rankings of colleges published since 1983 by U.S. News and World Report. Over time, the rankings became so popular that they outgrew the magazine itself and became a separate annual guidebook simply called Best Colleges. A number of other rankings have emerged as competitors, but the U.S. News rankings are the best known and most influential.

Although U.S. News no longer exists as a print magazine, the rankings continue through the guidebook and an accompanying website published every year in August that feature extensive information and advice about applying to college, as well as rankings based on reputational and complex statistical formulas. The yearly rankings drive the sales of Best Colleges and generate considerable media attention and controversy among those, including us, who believe the ranking process is fundamentally flawed.

Concern about the rankings is not new. More than 20 years ago, Gerhard Casper, the president of Stanford University, expressed his concern about the rankings to the editor of U.S. News as follows: “As the president of a university that is among the top‐ranked universities, I hope I have the standing to persuade you that much about these rankings—particularly their specious formulas and spurious precision—is utterly misleading.”10

Some kids want that acceptance letter to Harvard, Yale, or Princeton so desperately, but they really do not know why except to impress family, friends, whomever. It is one thing to include prestige as a factor in your list of schools. It is a problem when it becomes the only factor, and I am seeing this more and more.

Private counselor concerned about the emphasis on prestige

What Goes into the U.S. News Rankings?

For the 2016 rankings, a little less than one quarter—22.5 percent to be exact—of a college's ranking is based on reputational ratings it receives in the poll that U.S. News conducts annually of college presidents, provosts, admissions deans, and a small group of high school counselors. The administrators are asked to rate the academic quality of undergraduate programs at schools with the same mission as their own (for example, liberal arts colleges or research universities) on a scale of 1 to 5 from “marginal” to “distinguished,” with an option to respond “don't know.” The counselors are asked to rate both liberal arts colleges and research universities. Many of the recipients of the questionnaire acknowledge that they lack the kind of detailed knowledge of other colleges that they would need to respond meaningfully. Why would the president of George Washington University be familiar with the undergraduate program at Georgia Tech? The response rate is usually fairly low: less than 50 percent for college administrators and less than 10 percent for the high school counselors.

The remaining 77.5 percent of a college's ranking is based on data collected in five categories, each weighted in the final calculation as follows: retention and graduation rate (22.5 percent), faculty resources (20 percent), student selectivity (12.5 percent), financial resources (10 percent), alumni giving (5 percent), and graduation rate performance (7.5 percent).11

U.S. News collects all of these measures annually for each college, puts them into a formula that weights them differentially, and then computes an overall “ranking.” To avoid comparing apples with oranges, U.S. News ranks campuses of the same type, so that research universities and liberal arts colleges, for example, are ranked separately. (We'll discuss the differences between these two kinds of institutions, as well as others, in chapter 4 when we look at factors to consider in choosing colleges.) Every few years, U.S. News slightly modifies its formula, ostensibly to demonstrate its precision and respond to criticism.

Overall, the rankings don't change much from year to year, although a school's position may bounce up or down a few notches because of a change in the formula or some aberration in a statistic reported for a given year. Does its quality relative to its peers really change significantly in one or two years? We think not. Critics of the rankings argue that meaningful changes in college quality cannot be measured in the short term and that U.S. News changes the formula primarily to appear fresh and up‐to‐date—and to sell more guidebooks.

Now more than ever, people believe that the ranking—or the presumed hierarchy of “quality” or “prestige”—of the college or university one attends matters, and matters enormously. More than ever before, education is being viewed as a commodity . . . The large and fundamental problem is that we are at risk of it all seeming and becoming increasingly a game. What matters is less the education and more the brand.12

Lee Bollinger, president of Columbia University

More Concerns About Rankings

Critics have pointed out that although the U.S. News variables may contribute indirectly to educational quality (perhaps higher salaries lead to more motivated faculty members, and smaller classes mean more personal attention), educators do not agree on how those variables can be used to measure the quality of a college. To make things worse, colleges can manipulate directly or indirectly some of the factors in the U.S. News formula to raise their standing. Alumni, boards of trustees, and even bond‐rating agencies on Wall Street pay close attention to the rankings and expect to see “improvement.” As much as college leaders disparage rankings, they are too high profile and too influential to be ignored.

While rankings such as this should always be taken with a grain of salt, it is certainly a clear sign that we are a top university and recognized as such.13

College president commenting on just‐released rankings showing an improvement for his school

Under pressure, some colleges have actively worked to look better in ways that have little to do with educational quality but will boost the school's ranking. One common but harmless approach that has been used for many years is the production of elegant, full‐color booklets that typically highlight a college's new programs and facilities, as well as its ambitious plans for the future. In addition to distributing them for fundraising and other purposes, some college presidents send them to their colleagues at other campuses in the hope that the booklets will raise awareness of their college and possibly lead to a higher reputation rating when the U.S. News questionnaire arrives the following year. No one knows if this actually works, but some colleges expend considerable effort in the hope that it does. Much more troubling are recent disclosures by several well‐known colleges that admissions staff members misrepresented data used in the rankings in an apparent effort to enhance their school's position.

WHY ARE RANKINGS SO POPULAR?

It is not surprising that students and parents turn to rankings such as those published by U.S. News when they think about colleges. Deciding where to apply isn't easy, and having supposed experts do the evaluating is an attractive alternative to trying to figure things out on your own, especially if you have no experience. We accept ratings that assess washing machines, restaurants, football teams, hospitals, and movies, so why not colleges, too?

College rankings, though, are very different. Although they offer the illusion of precision, the rankings simply don't measure what most people think they measure: the educational experience for an individual student. Doing that requires a personal look at a college through the eyes of that student. No standardized ranking can hope to evaluate how you as an individual might fare at a certain college.

There is no easy substitute for investing the time and effort to determine which colleges will be a good fit for you. Merely knowing which ones are the most selective or enjoy the highest reputations among college administrators (which, as we have said, is essentially what the U.S. News rankings are telling you) doesn't get you very far toward finding a place where you will thrive and learn.

ADMISSIONS RATE AND YIELD AND HOW THEY CONTRIBUTE TO COLLEGE FRENZY

Rankings aside, a college's admissions rate or selectivity is the one figure that captures the public's attention and the most headlines. A decline in the admit rate from the previous year is often interpreted as a reflection of a college's increased quality, not just the result of successful marketing. Sample headline: “College X Admits Record Low Percentage of Applicants.” This is news.

Factors That Affect Admissions Rate

Aggressive outreach to students to encourage them to apply, although the college knows that they will admit only a fraction of those applying, is the easiest way for a college to become more selective. Although most colleges engage in outreach with more noble goals, such as increasing diversity, the result is the same. Rachel Toor, a former Duke University admissions officer, vividly describes her own experience: “I travel around the country whipping kids (and their parents) into a frenzy so that they will apply. I tell them how great a school Duke is academically and how much fun they will have socially. Then, come April, we reject most of them.”14

I overheard a conversation at a reception for the parents of newly admitted students. A mom was chatting with a young admissions officer who was mingling with parents on the lawn of the president's house. “I have a question I'd like to ask you,” she said. “Since Elite U takes less than 15 percent of those who apply, why does the university work so hard to encourage more applications?” The admissions officer was silent for a moment. “I'm afraid you'll have to ask the dean of admissions that question,” she said.

Parent of prospective freshman

Colleges can also lower their admissions percentage by offering admission to those students who are most likely to enroll. Yield—the percentage of admitted students who decide to enroll—varies greatly from college to college, from about 80 percent at Stanford and Harvard to less than 20 percent at many others. A college with a high yield can admit fewer students and still fill its classes. If it has a low yield, it has to admit more to meet enrollment targets.

Ways Colleges Can Increase Their Yield

High yields are prized as a symbol of a college's attractiveness to potential freshmen. There are several admissions practices that will increase yield.

Accepting More Early Decision Applicants

A college can raise its yield by admitting a larger percentage of the incoming class by early decision, often referred to as ED. Through an ED application, students submit a completed application by November 1 or November 15 rather than the traditional January 1 deadline, in exchange for receiving an admission decision by mid‐December rather than in the spring. The catch is that an ED application is binding on the student, meaning that the student is obligated to attend if admitted, subject to the availability of adequate financial aid. So a student admitted by ED is a sure thing for a college. The yield is close to 100 percent. We'll talk much more about ED and its cousin, early action, in chapter 7, but we mention it now because it indirectly increases a college's overall yield and thereby reduces its overall admit rate. Some colleges admit from a third to more than half of their incoming freshman class under ED.

Wait‐Listing the “Overqualified”

A college may also increase its yield and lower its admit rate by rejecting or, more likely, wait‐listing students they consider “overqualified” because the college believes the student won't accept the college's offer of admission and will go elsewhere. The dean of admissions at one such college realistically defended the practice at his institution as follows: “We know our place in the food chain of higher education. We're not a community college. And we're not Harvard.” This practice is not common, but it is not rare either.15

Considering Demonstrated Interest

Finally, a college may increase its yield by preferentially admitting students who have shown that they are strongly interested in that school in some way beyond simply submitting an application. Colleges know from experience that students who connect with a college in different ways beyond submitting an application are more likely to enroll if offered admission than students who do not make such a connection. Some colleges, but not all, take this into account when they make their decisions. We'll talk more about “demonstrated interest” and its role in admissions in chapter 10.

“I'LL MAKE MORE MONEY IF I GRADUATE FROM AN ELITE COLLEGE”: A MYTH

Let's return now to the basic question of why there is so much interest in the most selective colleges. Okay, you say, you now see that name recognition and rankings do not necessarily equal educational quality. But maybe that is irrelevant to you. Isn't the value of an elite college education the contacts you make while there? Everyone knows that the rich, the famous, and the well‐connected attended these colleges. Wouldn't attending one of them increase your chances of getting to know the right people, getting into a prestigious graduate school, or getting an important career‐enhancing break—all eventually leading to fortune if not fame?

Students may have a better sense of their potential ability than college admissions committees. To cite one prominent example, Steven Spielberg was rejected by the University of Southern California and UCLA film schools.16

Stacey Dale and Alan Krueger, researchers who studied the long‐term effects of attending different types of colleges

The Association Between Income and College Selectivity

Several studies have been interpreted as supporting this conclusion. Years after graduation, graduates of elite institutions on average earn more than graduates of less well‐known colleges, just as the income of college graduates is higher those with a high school education. The simple interpretation is that attending a selective college is responsible for the income difference. But economists Stacy Dale and Alan Krueger investigated another possibility in two studies conducted a decade apart. Perhaps, they hypothesized, the students who apply to elite colleges have personal qualities to begin with that lead in some way to later income differences.

The Characteristics of the Student, and Not the College, Are Key

When Dale and Krueger controlled for a student's grade point average and test scores on entering college, they found no difference years later in the income of students who attended elite colleges versus those who had applied, were denied, and subsequently attended less selective schools. Students of similar academic ability who had the self‐confidence and motivation to envision themselves attending a selective college showed the economic benefit usually ascribed to those who actually attended such a college. However, some subgroups of students—African American and Hispanic students as well as those from less‐educated or low‐income families—did show significantly increased future earnings associated with attending a selective college. Overall, with these exceptions, Dale and Krueger's research suggests that the kind of college that students attend is less important than their inherent ability, motivation, and ambition.