6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

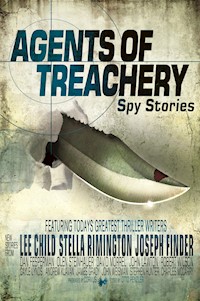

A unique collection of brand-new spy stories from world-class writers. An instant classic for thrill addicts everywhere. Features a brand new short story from Lee Child From a secretive soldier on the eve of the Normandy landings to a golf-playing gun fanatic in a suburb of modern Britain, everybody has something to hide in this brilliant collection of original spy fiction that brings together the distinctive voices of the genre for the very first time. In Lee Child's 'Section 7', a Top Secret operational meeting is given a sly twist, while David Morrell's tale of an interrogator's techniques in a world where the tables might turn at any moment is dark, sinister and frighteningly real. In a business where one country's traitor is another country's hero, how far would you go to get to the truth? With an introduction from Otto Penzler, these thrilling tales of intrigue and deception, heroism and betrayal, courage and cowardice will push your adrenaline to dangerous new levels. With contributions from: Charles McCarry, Lee Child, James Grady, Joseph Finder, John Lawton, John Weisman, Stephen Hunter, Gayle Lynds, David Morrell, Andrew Klavan, Robert Wilson, Dan Fesperman, Stella Rimington, Olen Steinhauer.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

Copyright

First published in the United States of America in 2010 by Vintage Crime/Black Lizard

This edition first published in Great Britain in 2010 by Corvus, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Otto Penzler 2010.

The moral right of Otto Penzler to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

First eBook Edition: January 2010

ISBN: 978-1-848-87996-6

Corvus

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26-27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Steve Ritterman

With fond memories of

the masked ball in Vladivostok

and that fearsome dark bar in Prague

Contents

Cover

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

THE END OF THE STRING

SECTION 7 (A) (OPERATIONAL)

DESTINY CITY

NEIGHBORS

EAST OF SUEZ, WEST OF CHARING CROSS ROAD

FATHER’S DAY

CASEY AT THE BAT

MAX IS CALLING

THE INTERROGATOR

SLEEPING WITH MY ASSASSIN

THE HAMBURG REDEMPTION

THE COURIER

HEDGED IN

YOU KNOW WHAT’S GOING ON

INTRODUCTION

Otto Penzler

THE INTERNATIONAL THRILLER is one of the most successful literary genres in the world, its primary practitioners becoming household names, insofar as any author’s level of fame can compete with an entertainer, sports figure, or world-class criminal. Ian Fleming, John le Carré, Graham Greene, Lee Child, Nelson DeMille, Frederick Forsyth, Robert Ludlum, Ken Follett, and Eric Ambler, among many others, are familiar to readers around the world. It will come as little surprise to learn that for many years, one of every four novels sold in the United States fell into the espionage or international adventure category.

What may come as a surprise, if not an outright shock, is that there never has been, until now, a collection of original stories devoted to this highly respected and challenging genre. There have been a modest number of collections by individual authors largely devoted to what used to be called cloak-and-dagger stories. Fleming’s For Your Eyes Only contained five James Bond adventures; Peter O’Donnell’s Cobra Trap collected Modesty Blaise stories; E. Phillips Oppenheim, the hugely popular thriller writer who wrote prolifically between the two world wars (as well as before) produced numerous collections. There are a few other volumes, mostly obscure, and quite a few mixed collections by such writers as Greene, Ambler, John Buchan, H. C. McNeile, and Forsyth, in which a small number of spy stories are surrounded by other types of fiction.

The number of important authors in this very large genre who have never written even a single short story is legion. Ludlum never wrote one, nor did Dan Brown, Tom Clancy, Follett, Alan Furst, Robert Littell, Daniel Silva, W. E. B. Griffin, Thomas Gifford, or Trevanian.

The few anthologies devoted to spy and thriller stories are all reprint collections, jostling for the right to reprint le Carré’s lone spy story and several familiar tales along with some obscure (though often very good) narratives. Alan Furst’s excellent anthology, The Book of Spies, is devoted to excerpts from novels.

One could reasonably wonder why this scarcity of short fiction by otherwise often prolific authors persists, and the explanation is simple. Short stories set in the complex world of international espionage and adventure are very, very difficult to write. A disproportionate number of novels in that category, you will have noticed, are big, fat books. Although they are seldom leisurely, they are nonetheless longer than most novels. Establishing characters and places, creating plots within plots within plots, arranging treachery and duplicity in a credible fashion within the political alliances and betrayals of the time, all take subtlety and explanation—and a lot of pages. To attempt to contain all these disparate but necessary elements in a story of twenty or thirty pages is a challenge few can manage. What often captivates the reader of this compelling fiction is not the outcome of whatever the struggle has been. We know World War II will break out. We know de Gaulle will not be assassinated. We know Hitler will not be killed by German officers. What is terrifically engaging is watching the principal characters struggle with the moral compromises they are forced to make through fear or accommodation.

Every story you are about to read, to a greater or lesser degree, deals with these issues. Some adopt a fundamental theology of right and wrong, home country versus enemy state, while others assume the philosophical position of much contemporary espionage fiction, filled with ambiguity and relativism. One country’s traitor is another’s hero, a duplicitous lying swine to one organization is viewed as a stalwart figure of brilliance and courage by another. There is a broad spectrum of political and philosophical ideology represented on these pages, but it is rarely overt or obvious. The single quality that the contributors to this unique collection share is an ability to tell a complex story in a simple manner. I once asked Eric Ambler what he regarded as the most difficult element of writing the kind of novels he wrote, and he said, “to make it simple.” Mr. Ambler, I believe, would have approved of the stories collected here by these distinguished authors, a veritable who’s who of today’s most highly regarded thriller writers, as well as the most widely read.

In a relatively brief time, Lee Child has established himself as one of the best-selling thriller writers in the world. His novels about Jack Reacher, the powerful giant of a man who fearlessly behaves heroically, consistently achieve the number-one spot on the best-seller list of The New York Times and are equally successful in Great Britain.

Dan Fesperman has had a distinguished career as a journalist, covering events in thirty countries, beginning with the first Gulf War in 1991. The (British) Crime Writers’ Association named Lie in the Dark the best first novel of 1999 and The Small Boat of Great Sorrows the best thriller of 2003; USA Today named The Prisoner of Guantánamo the best thriller of 2006.

The first career choice of Joseph Finder was to be a spy and he was even recruited by the CIA but quickly deduced that life in the bureaucratic world was less exciting than it was portrayed in fiction. His first novel, The Moscow Club, was named one of the ten greatest espionage novels of all time by Publishers Weekly. “Neighbors” is his first short story.

One of the half dozen most famous espionage novels of all time is James Grady’s Six Days of the Condor, successfully filmed with Robert Redford as Three Days of the Condor. Working as an investigative reporter for syndicated columnist Jack Anderson and for Senator Lee Metcalf helped provide the background information that makes his fiction so realistic.

As one of America’s most distinguished film critics, Stephen Hunter won a Pulitzer Prize in 2003, but he is even better known for his best-selling, intricately plotted thrillers, especially those about macho Vietnam veteran sniper Bob Lee Swagger, known as “The Nailer.” The first Swagger novel, Point of Impact, was filmed in 2007 as Shooter, starring Mark Wahlberg.

The controversial Andrew Klavan writes blogs and op-ed pieces at a prodigious rate, but it is crime fiction, notably such novels as Don’t Say a Word, which was later filmed starring Michael Douglas, and True Crime, directed by and starring Clint Eastwood, that has put him atop the best-seller lists around the world. His first politically incorrect thriller was Empire of Lies.

Although John Lawton’s Chief Inspector Troy works for Scotland Yard, he mainly finds himself caught up in international intrigue. His first case, Black Out, won the WHSmith Fresh Talent Award. A Little White Death was a 2007 New York Times Notable Book. London’s Daily Telegraph’s “50 Crime Writers to Read Before You Die” included Lawton, one of only six living English writers on the list.

A member of the U.S. Association for Intelligence Officers, Gayle Lynds is a cofounder (with David Morrell) of the International Thriller Writers. Among her best sellers are Masquerade, named one of the ten best spy novels of all time by Publishers Weekly; Mosaic, picked as the thriller of the year by Romantic Times; and three volumes in the Covert-One series coauthored with Robert Ludlum.

After serving in deep cover with the CIA for a decade, Charles McCarry was a speechwriter for the Eisenhower administration before becoming an editor-at-large for National Geographic. He has often been described as the greatest American writer of espionage fiction, producing such poetic masterpieces as The Tears of Autumn, The Secret Lovers, and The Last Supper, all featuring his hero, Paul Christopher.

Although he has published more than thirty books, had David Morrell stopped writing after his first novel, his legacy would have been assured. First Blood introduced Rambo, who in books and Sylvester Stallone films has become one of the iconic American adventure heroes. Morrell also wrote The Brotherhood of the Rose, upon which NBC based what became the most-watched miniseries in history.

After more than three decades in all three branches of the British Secret Service (MI5)—counterespionage, countersubversion, and counterterrorism—Stella Rimington was named the first female Director-General of the agency, serving from 1992 to 1996; she was made a Dame Commander of Order of the Bath (DCB) the year she retired. Upon stepping down, she wrote a candid memoir, Open Secret, followed by five espionage novels.

Olen Steinhauer’s first novel, The Bridge of Sighs, began a five-book thriller series chronicling Eastern Europe during the Cold War, a decade at a time until the fall of communism. It was nominated for five mystery awards, including an Edgar, as was his fourth book, Liberation Movements. The film rights to The Tourist, his first nonseries novel, were acquired by George Clooney, who plans to star in the motion picture.

One of the rare authors who has been on the New York Times best-seller list for fiction and nonfiction, John Weisman cowrote Rogue Warrior, the real-life story of the navy’s elite counterterrorism unit of the SEALS and its commander, which was on the list for eight months, four weeks in the top spot. Five fictional sequels made the list. His books have twice been the subject of Mike Wallace episodes of 60Minutes.

Portugal’s neutrality in World War II is the background for Robert Wilson’s A Small Death in Lisbon, which won the (British) Crime Writers’ Association Gold Dagger as the best novel of 1999, and his spy thriller The Company of Strangers. He was nominated for another Gold Dagger for the first of four Javier Falcón novels set in Spain, The Blind Man of Seville.

The assignment given to the contributors to this unique collection was deceptively straightforward and simple: Write an international espionage or thriller story and set it anyplace in the world you like, in any era. No subject was forbidden, no word length specified, no political position denied, no philosophy advanced or hindered. The wide range of styles and focus contained herein will attest to the fact that the men and women who labored over these stories and produced such masterly tales accepted the invitation in the proper spirit.

THE END OF THE STRING

Charles McCarry

I FIRST NOTICED the man I will call Benjamin in the bar of the Independence Hotel in Ndala. He sat alone, drinking orange soda, no ice. He was tall and burly—knotty biceps, huge hands. His short-sleeved white shirt and khaki pants were as crisp as a uniform. Instead of the usual third-world Omega or Rolex, he wore a cheap plastic Japanese watch on his right wrist. No rings, no gold, no sunglasses. I did not recognize the tribal tattoos on his cheeks. He spoke to no one, looked at no one. He himself might as well have been invisible as far as the rest of the customers were concerned. No one spoke to him or offered to buy him a drink or asked him any questions. He seemed poised to leap off his bar stool and kill something at a moment’s notice.

He was the only person in the bar I did not already know by sight. In those days, more than half a century ago, when an American was a rare bird along the Guinea coast, you got to know everyone in your hotel bar pretty quickly. I was standing at the bar, my back to Benjamin, but I could see him in the mirror. He was watching me. I surmised that he was gathering information rather than sizing me up for robbery or some other dark purpose.

I called the barman, put a ten-shilling note on the bar, and asked him to mix a pink gin using actual Beefeater’s. He laughed merrily as he pocketed the money and swirled the bitters in the glass. When I looked in the mirror again, Benjamin was gone. How a man his size could get up and leave without being reflected in the mirror I do not know, but somehow he managed it. I did not dismiss him from my thoughts, he was too memorable for that, but I didn’t dwell on the episode either. I could not, however, shake the feeling that I had been subjected to a professional appraisal. For an operative under deep cover, that is always an uncomfortable experience, especially if you have the feeling, as I did, that the man who is giving you the once- over is a professional who is doing a job that he has done many times before.

I had come to Ndala to debrief an agent. He missed the first two meetings, but there is nothing unusual about that even if you’re not in Africa. On the third try, he showed up close to the appointed hour at the appointed place: two a.m. on an unpaved street in which hundreds of people, all of them sound asleep, lay side by side. It was a moonless night. No electric light, no lantern or candle, even, burned for at least a mile in any direction. I could not see the sleepers, but I could feel their presence and hear them exhale and inhale. The agent, a member of parliament, had nothing to tell me apart from his usual bagful of pointless gossip. I gave him his money anyway, and he signed for it with a thumbprint by the light of my pocket torch. As I walked away I heard him ripping open his envelope and counting banknotes in the dark.

I had not walked far when a car turned into the street with headlights blazing. The sleepers awoke and popped up one after another as if choreographed by Busby Berkeley. The member of parliament had vanished. No doubt he had simply lain down with the others, and two of the wide-open eyes and one of the broad smiles I saw dwindling into the darkness belonged to him.

The car stopped. I kept walking toward it, and when I was beside it, the driver, who was a police constable, leaped out and shone a flashlight in my face. He said, “Please get in, master.” The British had been gone from this country for only a short time, and the locals still addressed white men by the title preferred by their former colonial rulers. The old etiquette survived in English, French, and Portuguese in most of the thirty-two African countries that had become independent in a period of two and a half years—less time than it took Stanley to find Livingstone.

I said, “Get in? What for?”

“This is not a good place for you, master.”

My rescuer was impeccably turned out in British tropical kit—blue service cap, bush jacket with sergeant’s chevrons on the shoulder boards, voluminous khaki shorts, blue woolen knee socks, gleaming oxfords, black Sam Browne belt. A truncheon dangling from the belt seemed to be his only weapon. I climbed into the backseat. The sergeant got behind the wheel, and using the rearview mirror rather than looking behind him, backed out of the street at breathtaking speed. I kept my eyes on the windshield, expecting him to plow into the sleepers at any moment. They themselves seemed unconcerned, and as the headlights swept over them they lay down one after the other with the same precise timing as before.

The sergeant drove at high speed through backstreets, nearly every one of them another open-air dormitory. Our destination, as it turned out, was the Equator Club, Ndala’s most popular nightclub. This structure was really just a fenced-in space, open to the sky. Inside, a band played highlife, a kind of hypercalypso, so loudly that you had the illusion that the music was visible as it rose into the pitch-black night.

The music was even louder. The air was the temperature of blood. The odors of sweat and spilled beer were sharp and strong. Guttering candles created a substitute for light. Silhouettes danced on the hard dirt floor, cigarettes glowed. The sensation was something like being digested by a tyrannosaurus rex.

Benjamin, alone again, sat at another small table. He was drinking orange soda again. He, too, wore a uniform. Though made of finer cloth, it was a duplicate of the sergeant’s, except that he was equipped with a swagger stick instead of a baton and the badge on his shoulder boards displayed the wreath, crossed batons, and crown of a chief constable. Benjamin, it appeared, was the head of the national police. He made a gesture of welcome. I sat down. A waiter placed a pink gin with ice before me with such efficiency, and was so neatly dressed, that I supposed he was a constable, too, but undercover. I lifted my glass to Benjamin and sipped my drink.

Benjamin said, “Are you a naval person?”

I said, “No. Why do you ask?”

“Pink gin is the traditional drink of the royal navy.”

“Not rum?”

“Rum is for the crew.”

I had difficulty suppressing a grin. Our exchange of words sounded so much like a recognition code used by spies that I wondered if that’s what it really was. Had Benjamin got the wrong American? He did not seem the type to make such an elementary mistake. He looked down on me—even while seated he was at least a head taller than I was—and said, “Welcome to my country, Mr. Brown. I have been waiting for you to come here again, because I believe that you and I can work together.”

Brown was one of the names I had used on previous visits to Ndala, but it was not the name on the passport I was using this time. He paused, studying my face. His own face showed no flicker of expression.

Without further preamble, he said, “I am contemplating a project that requires the support of the United States of America.”

The dramaturgy of the situation suggested that my next line should be, “Really?” or “How so?” However, I said nothing, hoping that Benjamin would fill the silence.

Frankly, I was puzzled. Was he volunteering for something? Most agents recruited by any intelligence service are volunteers, and the average intelligence officer is a sort of latter-day Marcel Proust. He lies abed in a cork-lined room, hoping to profit by secrets that other people slip under the door. People simply walk in and for whatever motive, usually petty resentment over having been passed over for promotion or the like, offer to betray their country. It was also possible, unusual though that might be, that Benjamin hoped to recruit me.

His eyes bored into mine. His back was to the wall, mine to the dance floor. Behind me I could feel but not see the dancers, moving as a single organism. Through the soles of my shoes I felt vibration set up by scores of feet stamping in unison on the dirt floor. In the yellow candlelight I could see a little more expression on Benjamin’s face.

Many seconds passed before he broke the silence. “What is your opinion of the president of this country?”

Once again I took my time answering. The problem with this conversation was that I never knew what to say next.

Finally I said, “President Ga and I have never met.”

“Nevertheless you must have an opinion.”

And of course I did. So did everyone who read the newspapers. Akokwu Ga, president for life of Ndala, was a man of strong appetites. He enjoyed his position and its many opportunities for pleasure with an enthusiasm that was remarkable even by the usual standards for dictators. He possessed a solid gold bathtub and bedstead. He had a private zoo. It was said that he was sometimes seized by the impulse to feed his enemies to the lions. He had deposited tens of millions of dollars from his country’s treasury into personal numbered accounts in Swiss banks.

Dinner for him and his guests was flown in every day from one of the restaurants in Paris that had a three-star rating in the Guide Michelin. A French chef heated the food and arranged it on plates, an English butler served it. Both were assumed to be secret agents employed by their respective governments. Ga maintained love nests in every quarter of the capital city. Women from all over the world occupied these cribs. The ones he liked best were given luxurious houses formerly occupied by Europeans and provided with German cars, French champagne, and “houseboys” (actually undercover policemen) who kept an eye on them.

“Speak,” Benjamin said.

I said, “Frankly, chief constable, this conversation is making me nervous.”

“Why? No one can bug us. Listen to the noise.”

How right he was. We were shouting at each other in order to be heard above the din. The music made my ears ring, and no microphone then known could penetrate it. I said, “Nevertheless, I would prefer to discuss this in private. Just the two of us.”

“And how then will you know that I am not bugging you? Or that someone else is not bugging both of us?”

“I wouldn’t. But would it matter?”

Benjamin examined me for a long moment. Then he said, “No, it wouldn’t. Because I am the one who will be saying dangerous things.”

He got to his feet, uncoiled would be the better word. Instantly the sergeant who had brought me here and three other constables in plain clothes materialized from the shadows. Everyone else was dancing, eyes closed, seemingly in another world and time. Benjamin put on his cap and picked up his swagger stick.

He said, “Tomorrow I will come for you.”

With that, he disappeared, leaving me without a ride. Eventually I found a taxi back to the hotel. The driver was so wide awake, his taxi so tidy, that I assumed that he, too, must be one of Benjamin’s men.

The porter who brought me my mug of tea at six a.m. also brought me a note from Benjamin. The penmanship was beautiful. The note was short and to the point: “Nine o’clock, by the front entrance.”

Through the glass in the hotel’s front door, the street outside was a scene from Goya, lepers and amputees and victims of polio or smallpox or psoriasis, and among the child beggars a few examples of hamstringing by parents who needed the income that a crippled child could bring home. A tourist arrived in a taxi and scattered a handful of change in order to disperse the beggars while he made his dash for the entrance. Clearly he was a greenhorn. The seasoned traveler in Africa distributed money only after checkout. To do so on arrival guaranteed your being fondled by lepers every time you came in or went out. One particularly handsome, smiling young fellow who had lost his fingers and toes to leprosy caught coins in his mouth.

At the appointed time exactly Was I still in Africa? Benjamin’s sergeant pulled up in his gleaming black Austin. He barked a command in one of the local languages, and once again the crowd parted. He took me by the hand in the friendly African way and led me to the car.

We headed north, out of town, horn sounding tinnily at every turn of the wheels. Otherwise, the sergeant explained, pedestrians would assume that the driver was trying to kill them. In daylight when everyone was awake and walking around instead of sleeping by the wayside, Ndala sounded like the overture of An American in Paris. After a hair-raising drive past the brand-new government buildings and banks of down-town, through raucous streets lined with shops and filled with the smoke of street vendors’ grills, through labyrinthine neighborhoods of low shacks made from scraps of lumber and tin and cardboard, we arrived at last in Africa itself, a sun-scorched plain of rusty soil, dotted with stunted bush, stretching from horizon to horizon. After a mile or so of emptiness, we came upon a policeman seated on a parked motorcycle. The sergeant stopped the car, leaped out, and leaving the motor running and the front door open, opened the back door to let me out. He gave me a map, drew himself up to attention, and after stamping his right foot into the dust, gave me a quivering British hand salute. He then jumped onto the motorcycle behind its rider, who revved the engine, made a slithering U-turn, and headed back toward the city trailed by a corkscrew of red dust.

I got into the Austin and started driving. The road soon became a dirt trail whose billowing ocher dust stuck to the car like snow and made it necessary to run the windshield wipers. It was impossible to drive with the windows open. The temperature inside the closed vehicle ( air-conditioning was a thing of the future) could not have been less than one hundred degrees Fahrenheit. Slippery with sweat, I followed the map, and after making a right turn into what seemed to be an impenetrable thicket of rubbery bushes, straddled a footpath which in time opened onto a clearing containing a small village. Another car, a dusty black Rover, was parked in front of one of the conical mud huts. This place was deserted. Grass had grown on the footpaths. There was no sign of life.

I parked beside the other car and ducked into the mud hut. Benjamin, alone as usual, sat inside. He wore national dress—the white togalike gown invented by nineteenth-century missionaries to clothe the natives for the benefit of English knitting mills. His feet were bare. He seemed to be deep in thought and did not greet me with word or sign. A . 455-caliber Webley revolver lay beside him on the floor of beaten earth. The light was dim, and because I had come into the shadowy interior out of intense sunlight, it was some time before I was able to see his face well enough to be absolutely certain that the mute tribesman before me actually was the chief constable with whom I had passed a pleasant hour the night before in the Equator Club. As for the revolver, I can’t explain why I trusted this glowering giant not to shoot me just yet, but I did.

Benjamin said, “Is this meeting place sufficiently private?”

“It’s fine,” I replied. “But where have all the people gone?”

“To Ndala, a long time ago.”

All over Africa were abandoned villages like this one whose inhabitants had packed up and left for the city in search of money and excitement and the new life of opportunity that independence promised. Nearly all of them now slept in the streets.

“As I said last night,” Benjamin said, “I am thinking about doing something that is necessary to the future of this country, and I would like to have the encouragement of the United States government.”

“It must be something impressive if you need the encouragement of Washington.”

“It is. I plan to remove the present government of this country and replace it with a freely elected new government.”

“That is impressive. What exactly do you mean by ‘encouragement’?”

“A willingness to stand aside, to make no silliness, and afterwards to be helpful.”

“Afterwards? Not before?”

“Before is a local problem.”

The odds were at least even that afterward might be a large problem for Benjamin. President Ga’s instinct for survival was highly developed. Others, including his own brother, had tried to overthrow him. They were all dead now.

I said, “I recommend first of all that you forget this idea of yours. If you can’t do that, then you should speak to somebody in the American embassy. I’m sure you already know the right person.”

“I prefer to speak to you.”

“Why? I’m not a member of the Ministry of Encouragement.”

“But that is exactly what you are, Mr. Brown. You are famous for it. You can be trusted. This man in the American embassy you call ‘the right person’ is in fact a fool. He is an admirer of President for Life Ga. He plays ball with President Ga. He cannot be trusted.”

I started to answer this nonsense. Benjamin showed me the palm of his hand. “Please, no protestations of innocence. I have all the evidence I would ever need about your good works in my country, should I ever need it.”

That made me blink. No doubt he did have an interesting file on me. I had done a good deal of mischief in his country, even before the British departed, and for all I knew his courtship was a charade. He might very well be trying to entrap me.

I said, “I’m flattered. But I don’t think I’d make a good assistant in this particular matter.”

Something like a frown crossed Benjamin’s brow. I had annoyed him. Since we were in the middle of nowhere and he was the one with the revolver, this was not a good sign.

“I have no need of an assistant,” Benjamin said. “What I need is a witness. A trained observer whose word is trusted in high places in the U.S. Someone who can tell the right people in Washington what I have done, how I have done it, and most of all, that I have done it for the good of my country.”

I could think of nothing to say that would not make this conversation even more unpleasant than it already was.

Benjamin said, “I can see that you do not trust me.”

He picked up the revolver and cocked it. The Webley is something of an antique, having been designed around the time of the Boer War as the standard British officer’s sidearm. It is large and ugly but also effective, powerful enough to kill an elephant. For a long moment Benjamin looked deeply into my eyes and then, holding the gun by the barrel, handed it to me.

“If you believe I am being false to you in any way,” he said, “you can shoot me.”

It was a wonder that he had not shot himself, handling a cocked revolver in such a carefree way. I took the weapon from his hand, lowered the hammer, swung open the cylinder, and shook out the cartridges. They were not blanks. I reloaded and handed the weapon back to Benjamin. He wiped it clean of fingerprints, my fingerprints, with the skirt of his robe and put it back on the floor.

In the jargon of espionage, the recruitment of an agent is called a seduction. As in a real seduction, assuming that things are going well, a moment comes when resistance turns into encouragement. We had arrived at the moment for a word of encouragement.

I said, “What exactly is the plan?”

“When you strike at a prince,” Benjamin said, “you must strike to kill.”

Absolutely true. It did not surprise me that he had read Machiavelli. At this point it would not have surprised me if he burst into fluent Sanskrit. Despite the rigmarole with the Webley, I still did not trust him and probably never would, but I was doing the work that I was paid to do, so I decided to press on with the thing.

“That’s an excellent principle,” I said, “but it’s a principle, not a plan.”

“All the right things will be done,” Benjamin said. “The radio station and newspapers will be seized, the army will cooperate, the airport will be closed, curfews will be imposed.”

“Don’t forget to surround the presidential palace.”

“That will not be necessary.”

“Why?”

“Because the president will not be in the palace,” Benjamin said.

All of a sudden, Benjamin was becoming cryptic. Frankly, I was just as glad, because what he was proposing in words of one syllable scared the bejesus out of me. So did the expression on his face. He was as calm as a Buddha.

He rose to his feet. In his British uniform he had looked impressive, if slightly uncomfortable. In his gown he looked positively majestic, a black Caesar in a white toga.

“You know enough now to think this over,” he said. “Do so, if you please. We will talk some more before you fly away.”

He ducked through the door and drove away. I waited for a few minutes, then went outside myself. A large black mamba lay in the sun in front of my car. My blood froze. The mamba was twelve or thirteen feet long. This species is the fastest-moving snake known to zoology, capable of slithering at fifteen miles an hour, faster than most men can run. Its strike is much quicker than that. Its venom will usually kill an adult human being in about fifteen minutes. Hoping that this one was not fully awake, I got into the car and started the engine. The snake moved but did not go away. I could easily have run over it, but instead I backed up and steered around it. Locally this serpent was regarded as a sign of bad luck to come. I wasn’t looking for any more misfortune than I already had on my plate.

After dinner that evening I spent an extra hour in the hotel bar. I felt the alcohol after I went upstairs and got into bed, and fell almost immediately into a deep sleep. Cognac makes for bad dreams and I was in the middle of one when I was awakened by the click of the latch. For an instant I thought the porter must be bringing my morning tea and wondered where the night had gone. But when I opened my eyes it was still dark outside. The door opened and closed. No light came in, meaning that the intruder had switched off the dim bulbs in the corridor. He was now inside the room. I could not see him but I could smell him: soap, spicy food, shoe polish. Shoe polish? I slid out of bed, taking the pillows and the covers with me and rolling them into a ball, as if this would help me defend myself against the intruder who I believed was about to attack me in the dark with a machete.

In the dark, the intruder drew the shade over the window. An instant later the lights came on. Benjamin said, “Sorry to disturb you.”

He wore his impeccable uniform, swagger stick tucked under his left arm, cap square on his head, badges and shoes and Sam Browne belt gleaming. The clock read 4:23. It was an old-fashioned windup alarm clock with two bells on top. It ticked loudly while I waited until I was sure I could trust my voice to reply. I was stark naked. I felt a little foolish to be holding a bundle of bedclothes in my arms, but at least this preserved my modesty.

Finally I said, “I thought we’d already had our conversation for the day.”

Benjamin ignored the Bogart impersonation. “There is something I want you to see,” he said. “Get dressed as quick as you can, please.” Benjamin never forgot a please or a thank you. Like his penmanship, Victorian good manners seemed to have been rubbed into his soul in missionary school.

As soon as I had tied my shoes, he led the way down the back stairs. He moved at a swift trot. Outside the back door, a black Rover sedan waited with the engine running. The sergeant stood at attention beside it. He opened the back door as Benjamin and I approached and, after a brief moment as Alphonse and Gaston, we got into the backseat.

When the car was in motion, Benjamin turned to me and said, “You seem to want to give President Ga the benefit of the doubt. This morning you will see some things for yourself, and then you can decide whether that is the Christian thing to do.”

It was still dark. As a usual thing there is no lingering painted sunrise in equatorial regions; the sun, huge and white, just materializes on the rim of the earth, and daylight begins. In the darkness, the miserable of Ndala were still asleep in rows on either side of every street, but little groups of people on the move were caught in our headlights.

“Beggars,” Benjamin said. “They are on their way to work.” The beggars limped and crawled according to their afflictions. Those who could not walk at all were carried by others.

“They help each other,” Benjamin said. He said something to the sergeant in a tribal language. The sergeant put a spotlight on a big man carrying a leper who had lost his feet. The leper looked over his friend’s shoulder and smiled. The big man walked onward as if unaware of the spotlight. Benjamin said, “See? A blind man will carry a crippled man, and the crippled man will tell him where to go. Take a good look, Mr. Brown. It is a sight you will never see in Ndala again.”

“Why not?”

“You will see.”

At the end of the street an army truck was parked. A squad of soldiers armed with bayoneted rifles held at port arms formed a line across the street. Benjamin gave an order. The sergeant stopped the car and shone his spotlight on them. They had not stirred or opened their eyes as when the sergeant drove down this same street the night before. Whatever was happening, these people did not want to be witnesses. The soldiers paid no more attention to Benjamin’s car than the people lying on the ground paid to the soldiers.

When the beggars arrived, the soldiers surrounded them and herded them into the truck. The blind man protested, a single syllable. Before he could say more, a soldier hit him in the small of the back with a rifle butt. The blind man dropped the crippled leper and fell down unconscious. The soldiers would not touch them, so the other beggars picked them up and loaded them into the truck, then climbed in themselves. The soldiers lowered the back curtain and got into a smaller truck of their own. All this happened in eerie silence, not an order given or a protest voiced, in a country in which the smallest human encounter sent tsunamis of shouting and laughter through crowds of hundreds.

We drove on. We witnessed the same scene over and over again. All over the city, beggars were being rounded up by troops. Our last stop was the Independence Hotel, my hotel, where I saw the beggars I knew best, including the handsome, smiling leper who caught coins in his mouth, being herded into the back of a truck. As the truck drove away, gears changing, the sun appeared on the eastern horizon, huge and entire, a miracle of timing.

Benjamin said, “You look a little sick, my friend. Let me tell you something. Those people are never coming back to Ndala. They give our country a bad image, and two weeks from now hundreds of foreigners will arrive for the Pan-African Conference. Thanks to President Ga, they will not have to look at these disgusting creatures, so maybe they will elect him president of the conference. Think about that. We will talk when you come back.”

In Washington, two days later at six in the morning, I found my chief at his desk, drinking coffee from a chipped mug and reading the Wall Street Journal. I told him my tale. He knew at once exactly who Benjamin was. He asked how much money Benjamin wanted, what his timetable was, who his coconspirators were, whether he himself planned to replace the abominable Ga as dictator after he overthrew him, what his policy toward the United States would be—and, by the way, what were his hidden intentions? I was unable to answer most of these questions.

I said, “All he’s asked for so far is encouragement.”

“Encouragement?” said my chief. “That’s a new one. He didn’t suggest one night of love with the first lady in the Lincoln bedroom?”

A certain third world general had once made just such a demand in return for his services as a spy in a country whose annual national product was smaller than that of Cuyahoga County, Ohio. I told him that Benjamin had not struck me as being the type to long for Mrs. Eisenhower.

My chief said, “You take him seriously?”

“He’s an impressive person.”

“Then go back and talk to him some more.”

“When?”

“Tomorrow.”

“What about the encouragement?”

“It’s cheap. Ga is a bad ’un. Shovel it on.”

I was cheap, too—a singleton out at the end of the string. If I got into trouble, I’d get no help from the chief or anyone else in Washington. The old gentleman himself would cut the string. He owed me nothing. “Brown? Brown?” he would say in the unlikely event that he would be asked what had become of me. “The only Brown I know is Charlie.”

The prospect of returning to Ndala on the next flight was not a very inviting one. I had just spent eight weeks traveling around Africa, in and out of countries, languages, time zones, identities. My intestines swarmed with parasites that were desperate to escape. There was something wrong with my liver: the whites of my eyes were yellow. I had had a malaria attack on the plane from London that frightened the woman seated next to me. The four aspirins I took, spilling only twenty or so while getting them out of the bottle with shaking hands, brought the fever and the sweating under control. Twelve hours later I still had a temperature of 102; I shuddered still, though only fitfully.

To the chief I said, “Right.”

“This time get all the details,” my chief said. “But no cables. Your skull only, and fly the information back to me personally. Tell the locals nothing.”

“Which locals? Here or there?”

“Anywhere.”

His tone was nonchalant, but I had known this man for a long time. He was interested; he saw an opportunity. He was a white- haired, tweedy, pipe-smoking old fellow with a toothbrush mustache and twinkling blue eyes. His specialty was doing the things that American presidents wanted done without actually requiring them to give the order. He smiled with big crooked teeth; he was rich but too old for orthodontia. “Until I give the word, nobody knows anything but us two chickens. Does that suit you?”

I nodded as if my assent really was necessary. After a breath or two, I said, “How much encouragement can I offer this fellow?”

“Use your judgment. Take some money, too. You may have to tide him over till he gets hold of the national treasure. Just don’t make any promises. Hear him out. Figure him out. Estimate his chances. We don’t want a failure. Or an embarrassment.”

I rose to leave.

“Hold on,” said the chief.

He rummaged around in a desk drawer and after examining several identical objects and discarding them, handed me a large bulging brown envelope. A receipt was attached to it with Scotch tape. It said that the envelope contained one hundred thousand dollars in hundred-dollar bills. I signed it with the fictitious name my employer had assigned to me when I joined up. As I opened the door to leave, I saw that the old gentleman had gone back to his Wall Street Journal.

Benjamin and I had arranged no secure way of communicating with each other, so I had not notified him that I was coming back to Ndala. Nevertheless, the sergeant met me on the tarmac at the airport. I was not surprised that Benjamin knew I was coming. Like all good cops, he kept an eye on passenger manifests for flights in and out of his jurisdiction. After sending a baggage handler into the hold of the plane to find my bag, the sergeant drove me to a safe house in the European quarter of the city. It was five o’clock in the morning when we got there. Benjamin awaited me. The sergeant cooked and served a complete English breakfast—eggs, bacon, sausage, fried potatoes, grilled tomato, cold toast, Dundee orange marmalade, and sour gritty coffee. Benjamin ate with gusto but made no small talk. Air conditioners hummed in every window.

“Better that you stay in this house than the hotel,” Benjamin said when he had cleaned his plate. “In that way there will never be a record that you have been in this country.”

That was certainly true, and it was not the least of my worries. I was traveling on a Canadian passport as Robert Bruce Brown, who had died of meningitis in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, thirty-five years before at age two. Thanks to the sergeant, I had bypassed customs and passport control. That meant that there was no entry stamp in the passport. In theory I could not leave the country without one, but then again, I was carrying one hundred thousand American dollars in cash in an airline bag, and this was a country in which money talked. If I did disappear, I would disappear without a trace. One way or another, so would the money.

“There is something I want you to see,” Benjamin said. Apparently this was his standard phrase when he had something unpleasant to show me. After wiping his lips on a white linen napkin, folding it neatly, and dropping it onto the table, he led me into the living room. The drapes were drawn. The sun was up. A sliver of white-hot sunlight shone through. Benjamin called to the sergeant, who brought his briefcase and pulled the curtains tighter. Before leaving us he started an LP on the hi-fi and turned up the volume to defeat hidden microphones. Sinatra sang “In the Still of the Night.”

Benjamin took a large envelope from the briefcase and handed it to me. It contained about twenty glossy black-and-white photographs—army trucks parked in a field; soldiers with bayonets fixed; a large empty ditch with two bulldozers standing by; beggars getting down from the truck; beggars being tumbled into the ditch; beggars, hedged in by bayonets, being buried alive by the bulldozers; bulldozers rolling over the dirt to tamp it down with their treads.

“The army is very unhappy about this,” Benjamin said. “President Ga did not tell the generals that soldiers would be required to do this work. They thought they were just getting these beggars out of sight until after the Pan-African Conference. Instead the soldiers were ordered to solve the problem once and for all.”

My throat was dry. I cleared it and said, “How many people were buried alive?”

“Nobody counted.”

“Why was this done?”

“I told you. The beggars were an eyesore.”

“That was reason enough to bury them alive?”

“The soldiers were supposed to shoot them first. But they refused. This is good for us, because now the army is angry. Also afraid. Now Ga can execute any general for murder simply by discovering the crime and punishing the culprits in the name of justice and the people. The generals have not told the president that the soldiers refused to follow his orders, so now they are in danger. If he ever finds out he will bury the soldiers alive. Also a general or two. Or more.”

I said, “Who would tell him?”

“Who indeed?” asked Benjamin, stone-faced. I handed the pictures back to him. He held up a palm. “Keep them.”

I said, “No, thank you.”

The photos were a death warrant for anyone who was arrested with them in his possession.

Benjamin ignored me. He rummaged in his briefcase and handed me a handheld radio transceiver. Technologically speaking, those were primitive days, and the device was not much smaller than a fifth of Beefeater’s, minus the neck of the bottle. Nevertheless, it was a wonder for its time. It was made in the U.S.A., so I supposed it had been supplied by the local chief of station, the man who played ball with Ga, as a trinket for a native.

Benjamin said, “Your call sign is Mustard One. Mine is Mustard. This is for emergencies. This, too.” He handed me a Webley and a box of hollow-point cartridges.

I was touched by his concern. But the transceiver was useless—if the situation was desperate enough to call him. I would be a dead man before he could get to me. The Webley, however, would be useful for shooting myself in case of need. Shooting anyone else in this country would be the equivalent of committing suicide.

Benjamin rose to his feet. “I will be back,” he said. “We will spend the evening together.”

When Benjamin returned around midnight, I was reading Sir Richard Burton’s Wanderings in West Africa, the only book in the house. It was a first edition, published in 1863. The margins were sprinkled with pencil dots. I guessed that it had been used by some romantic Brit for a book code. Benjamin was sartorially correct as usual—crisp white shirt with paisley cravat, double-breasted naval blazer, gray slacks, gleaming oxblood oxfords. He cast a disapproving eye on my wrinkled shorts and sweaty shirt and bare feet.

“You must wash and shave and put on proper clothes,” he said. “We have been invited to dinner.”

Benjamin offered no further information. I asked no questions. The sergeant drove, rapidly, without headlights on narrow trails through the bush. We arrived at a guard shack. The guard, a very sharp soldier, saluted and waved us through without looking inside the car. The road widened into a sweeping driveway. Gravel crackled under the tires. We reached the top of a little rise, and I saw before me the presidential palace, lit up like a football stadium by the light towers that surrounded it. The flags of all the newborn African nations flew from a ring of flagstaffs.

The soldiers guarding the front door, white belts, white gloves, white bootlaces, white rifle slings, came to present arms. We walked past them into a vast foyer from which a double staircase swept upward before separating at a landing decorated by a huge floodlit portrait of President Ga wearing his sash of office. A liveried servant led us up the stairs past a gallery of portraits of Ga variously uniformed as general of the army, admiral of the fleet, air chief marshal, head of the party, and other offices I could not identify.

We simply walked into the presidential office. No guards were visible. President Ga was seated behind a desk at the far end of the vast room. Two attack dogs, pit bulls, stood with ears pricked at either side of his oversize desk. The ceiling could not have been less than fifteen feet high. Ga, not a large person to begin with, was so diminished by these Brobdingnagian proportions that he looked like a puppet. He was reading what I supposed was a state paper, pen in hand in case he needed to add or cross something out. As we approached across the snow-white marble floor, our footsteps echoed. Benjamin’s were especially loud because he wore leather heels, but nothing, apparently, could break the president’s concentration.

About ten feet from the desk we stopped, our toes touching a bronze strip that was sunk into the marble. Ga ignored us. The pit bulls did not. Ga pressed a button. A hidden door opened behind the desk, and a young army officer in dress uniform stepped out. Behind him I could see half a dozen other soldiers, armed to the teeth and standing at attention in a closetlike space that was hardly large enough to hold them all.

Wordlessly, Ga handed the paper to the officer, who took it, made a smart about-face, and marched back into the closet. Ga stood up, still taking no notice of us, and strolled to the large window behind his desk. It looked out over the brightly lit, shadowless palace grounds. At a little distance I could see an enclosure in which several different species of gazelle were confined. In other paddocks—too many to be seen in a single glance—other wild animals paced. Ga drank in the scene for a long moment, then whirled and approached Benjamin and me at quick-march, as if he wore one of his many uniforms instead of the white bush jacket, black slacks, and sandals in which he actually was dressed. Benjamin did not introduce me. Apparently there was no need to do so, because Ga, looking me straight in the eye, shook my hand and said, “I hope you like French food, Mr. Brown.”

I did. The menu was a terrine of gray sole served with a 1953 Corton Charlemagne, veal stew accompanied by a 1949 Pommard, cheese, and grapes. The president ate the food hungrily, talking all the while, but only sipped the wines.

“Alcohol gives me bad dreams,” he said to me. “Do you ever have bad dreams?”

“Doesn’t everyone, sir?”

“My best friend, who died too young, never had bad dreams. He was too good in mind and heart to be troubled by such things. Now he is in my dreams. He visits me almost every night. Who is in your dreams?”

“Mostly people I don’t know.”

“Then you are very lucky.”

During the dinner Ga talked about America. He knew it well. He had earned a degree from a Negro college in Missouri. Baptist missionaries had sent him to the college on a scholarship. He graduated second in his class, behind his best friend who now called on him in dreams. When Ga spoke to his people he spoke standard Africanized English, the common tongue of his country where more than a hundred mutually incomprehensible tribal languages were in use. He spoke to me in American English, sounding like Harry S. Truman. He had had a wonderful time in college: the football games, the fraternity pranks, the music, the wonderful food, homecoming, the prom, those American coeds! His friend had been the school’s star running back; Ga had been the team manager; they had won their conference championship two years in a row. “From the time we were boys together in our village, my friend was always the star, I was always the administrator,” he said. “Until we got into politics and changed places. My friend stuttered. It was his only flaw. It is the reason I am president. Had he been able to speak to the people without making them laugh, he would be living in this house.”

“You were fond of this man,” I said.

“Fond of him? He was my brother.”

Tears formed in the president’s eyes. Despite everything I knew about his crimes, I found myself liking Akokwu Ga.

Servants arrived with coffee and a silver dessert bowl. “Ah, strawberries and crème fraîche!” said Ga, breaking into his first smile of the evening.

After the strawberries, another servant offered cigars and port, discreetly showing me the labels. Ga waved these temptations away like a good Baptist. I did the same, not without regret.

“Come, my friend,” said Ga, rising to his feet and suddenly speaking West African rather than Missouri English, “it is time for a walk. Do you get enough exercise?”

I said, “I wish I got more.”

“Ah, but you must make time to keep up to snuff,” said Ga. “I ride horseback every morning and walk in the cool of the evening. Both things are excellent exercise, and also, to start the day, you have the companionship of the horse which never says anything stupid. You must get a horse. If you are too busy for a horse, a masseur. Not a masseuse. They are too distracting. Massage is like hearty exercise if the masseur is strong and has the knowledge. Bob Hope told me that. Massage keeps him young.”

By now we were at the front door. The spick-and-span young army captain who had earlier leaped out of the closet behind Ga’s desk awaited us. Standing at rigid attention, he held out a paper for Ga. Benjamin immediately went into reverse, walking backward as he withdrew from eyeshot and earshot of the president, while the latter read his document and spoke to his orderly. I followed suit.

Staring straight ahead and barely moving his lips, Benjamin muttered, “He is charming tonight. Be careful.” These were the first words he had uttered all evening. Throughout dinner, Ga had ignored him entirely, as if he were a third pit bull lying at his feet.

Outside, under the stadium lights, Ga led the way across the shadowless grounds to his animal park. Three men walked in front, sweeping the ground in case of snakes. As I knew from rumor and intelligence reports, Ga had a morbid fear of snakes. Another bearer carried Ga’s sporting rifle, a beautiful weapon that looked to me like a Churchill, retail in London, £10,000.

The light from the towers was so strong that everything looked like an overexposed photograph. Ga pointed out the gazelles, naming them all one by one. “Some of these specimens are quite rare,” he said, “or so I am told by the people who sell them. I am preserving them for the people of this nation. Most of these beasts no longer live in this part of Africa, but before the Europeans came with their guns and killed them for sport, we knew them as brothers.”

Ga was a believer in raising a mythical African past to the status of reality. The public buildings he had built during his brief reign featured murals and mosaics depicting Africans of a lost civilization inventing agriculture, mathematics, architecture, medicine, electricity, the airplane, even the postage stamp. In his mind it was only logical that the ancients had also lived in peace with the lion, the elephant, the giraffe—everything but the serpent, which Ga had exiled from his utopia.

We tramped on a bit, to an empty paddock. “Now you will see something,” he said. “You will see nature in the raw.”

This paddock was unlighted. Ga lifted his hand, and the lights went on. Standing alone in the middle of the open space was an animal that even I was able to recognize as a Thomson’s gazelle from its diminutive size, its lovely tan and white coat, the calligraphic black stripe on its flank. This one was a buck, just over three feet tall, a work of art like so many other African animals.

“This type of gazelle is common,” Ga said. “There are hundreds of thousands of them in herds in Tanganyika. They can outrun a lion. Watch.”

The word suddenly does not convey the speed of what happened next. Out of the blinding light in which it had somehow been concealing itself as it stalked the Tommy, a cheetah materialized, moving at sixty miles an hour. A cheetah can cover a hundred meters in less than three seconds. The Tommy saw or sensed this blur of death that hurtled toward him and leaped three or four feet straight up into the air, then hit the ground running. The Tommy was slightly slower than its predator, but far more nimble. When the cheetah got close enough to attack, the little gazelle would make a quick turn and escape. This happened over and over again. The size of the paddock—or playing field, as Ga must have thought of it—was an advantage to the Tommy, who would lead the cheetah straight to the fence, then make a last-second turn. Once or twice the cheetah crashed into the wire.

“This is almost over,” Ga said. “Usually it lasts only a minute or so. If the cat does not win very quickly, it runs out of strength and gives up.”

A second later, the cheetah won. The gazelle turned in the wrong direction, and the cat brought it down. A cheetah is not strong enough to break the neck of its prey, so it kills by suffocation, biting the throat and crushing the windpipe. The Tommy struggled, then went limp. The cheetah’s eyes glittered. So did Ga’s.

Beaming, he threw an arm around my shoulders. He said, “Wonderful, eh?”

I smelled the food and wine on his breath, felt his excited heart beating against my shoulder. Then, without a good night or even a facial expression, Ga turned on his heel, and, surrounded by his snake sweepers and his gun bearer, marched away and disappeared into the palace. The evening was over. His guests had ceased to exist.

We lost no time in leaving. Minutes later, as we rolled toward the wakening city in Benjamin’s Rover, I asked a question.

“Is he always so hospitable?”

“Tonight you saw one Ga,” Benjamin said. “There are a thousand of him.”

I could believe it. In this one evening I had seen him in half a dozen incarnations, Mussolini redux, gourmet, Joe College, tender friend, zoologist, mythologist, and a fun-loving god who stage-managed animal sacrifices to himself.