Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

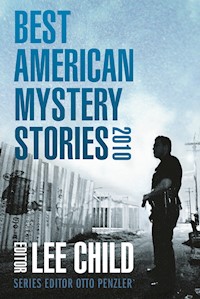

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: The Best American Mystery Stories

- Sprache: Englisch

A state of the Art collection: the world's bestselling crime writer complies his pick of the year's best crime writing. This year's guest editor is Lee Child, the creator of Jack Reacher and a simultaneous bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic. Featuring twenty of the year's standout crime short stories handpicked by one of the world's best thriller writers, Best American Mystery Stories 2010 showcases not only the very best of the crime genre, but the best of American writing full stop. Within its pages, literary legends rub shoulders with the hottest new talent. Contributors in the past have included James Lee Burke, Jeffrey Deaver, Michael Connelly, Alice Munro and Joyce Carol Oates.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 750

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

GUEST EDITORS OFTHE BEST AMERICAN MYSTERY STORIES

1997 ROBERT B. PARKER

1998 SUE GRAFTON

1999 ED MCBAIN

2000 DONALD E. WESTLAKE

2001 LAWRENCE BLOCK

2002 JAMES ELLROY

2003 MICHAEL CONNELLY

2004 NELSON DEMILLE

2005 JOYCE CAROL OATES

2006 SCOTT TUROW

2007 CARL HIAASEN

2008 GEORGE PELECANOS

2009 JEFFERY DEAVER

2010 LEE CHILD

Copyright

First published in the United States of America in 2010 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

This edition first published in Great Britain in 2010 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © 2010 Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company

Introduction copyright © 2010 by Lee Child

The moral right of Lee Child to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents act of 1988.

The Best American Series® is a registered trademark of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

The Best American Mystery StoriesTM is a trademark of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

ISBN: 978-0-857-89153-2

First eBook Edition: January 2010

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26-27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

“Charlie and the Pirates” by Gary Alexander. First published in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, January/February 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Gary Alexander. Reprinted by permission of Gary Alexander.

“The Emerald Coast” by R. A. Allen. First published in The Literary Review, Summer 2009. Copyright © 2009 by R. A. Allen. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“An Early Christmas” by Doug Allyn. First published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, January 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Doug Allyn. Reprinted by permission of Doug Allyn.

“Maynard” by Mary Stewart Atwell. First published in Alaska Quarterly Review, Fall/Winter 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Mary Stewart Atwell. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Dredge” by Matt Bell. First published in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Fall/Winter 2009–2010. Copyright © 2009 by Matt Bell. Reprinted by permission of Matt Bell.

“A Jury of His Peers” by Jay Brandon. First published in Murder Past, Murder Present, September 15, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Jay Brandon. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Designer Justice” by Phyllis Cohen. First published in The Prosecution Rests, April 14, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Herbert Cohen. Reprinted by permission of Herbert Cohen.

“The Cross-Eyed Bear” by John Dufresne. First published in Boston Noir, November 1, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by John Dufresne. Reprinted by permission of John Dufresne.

“The Case of Colonel Warburton’s Madness” by Lyndsay Faye. First published in Sherlock Holmes in America, November 1, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Lyndsay Faye. Reprinted by permission of Lyndsay Faye.

“The First Rule Is” by Gar Anthony Haywood. First published in Black Noir, March 3, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Gar Anthony Haywood. Reprinted by permission of Gar Anthony Haywood.

“Killing Time” by Jon Land. First published in Thriller 2, May 26, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Jon Land. Reprinted by permission of International Thriller Writers and Mira.

“Animal Rescue” by Dennis Lehane. First published in Boston Noir, November 1, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Dennis Lehane. Reprinted by permission of Ann Rittenberg Literary Agency, Inc.

“Tell Me” by Lynda Leidiger. First published in Gettysburg Review, Summer 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Lynda Leidiger. Reprinted by permission of Lynda Leidiger.

“The House on Pine Terrace” by Phillip Margolin. First published in Thriller 2, May 26, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Phillip Margolin. Reprinted by permission of Phillip Margolin.

“Bias” by Chris Muessig. First published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, July 1, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Chris Muessig. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Bismarck Rules” by Albert Tucher. First published in Oregon Literary Review, Summer/Fall 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Albert Tucher. Reprinted by permission of Albert Tucher.

“Ed Luby’s Key Club” from Look at the Birdie: Unpublished Short Fiction by Kurt Vonnegut, copyright © 2009 by The Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. Trust. Used by permission of Delacorte Press, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc.

“Custom Sets” by Joseph Wallace. First published in The Prosecution Rests, April 14, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Joseph Wallace. Reprinted by permission of Joseph Wallace.

“The Shipbreaker” by Mike Wiecek. First published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, March/April 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Mike Wiecek. Reprinted by permission of Michael Wiecek.

“Blood and Dirt” by Ryan Zimmerman. First published in Thuglit, issue 34, November/December 2009. Copyright © 2009 by Ryan Zimmerman. Reprinted by permission of Ryan Zimmerman.

Contents

Cover

GUEST EDITORS OF THE BEST AMERICAN MYSTERY STORIES

Copyright

Foreword

Introduction

GARY ALEXANDER

Charlie and the Pirates

R. A. ALLEN

The Emerald Coast

DOUG ALLYN

An Early Christmas

MARY STEWART ATWELL

Maynard

MATT BELL

Dredge

JAY BRANDON

A Jury of His Peers

PHYLLIS COHEN

Designer Justice

JOHN DUFRESNE

The Cross-Eyed Bear

LYNDSAY FAYE

The Case of Colonel Warburton’s Madness

GAR ANTHONY HAYWOOD

The First Rule Is

JON LAND

Killing Time

DENNIS LEHANE

Animal Rescue

LYNDA LEIDIGER

Tell Me

PHILLIP MARGOLIN

The House on Pine Terrace

CHRIS MUESSIG

Bias

ALBERT TUCHER

Bismarck Rules

KURT VONNEGUT

Ed Luby’s Key Club

JOSEPH WALLACE

Custom Sets

MIKE WIECEK

The Shipbreaker

RYAN ZIMMERMAN

Blood and Dirt

Contributors’ Notes

Other Distinguished Mystery Stories of 2009

Foreword

EVERY YEAR, when I sit down to write the foreword to the new edition of The Best American Mystery Stories, two thoughts leap to mind. The first is: what can I write about that I haven’t written about in the previous volumes? The second is: does anyone actually read it anyway, or do they (wisely) go straight to the fiction?

Well, just in case this book has found its way into the hands of a completist reader, here are a few things you should know.

Mystery is a very broad genre that includes any story in which a crime (usually murder) or the threat of a crime (creating suspense) is central to the plot or theme. Detective stories are one subgenre, others being crime (often told from the point of view of the criminal), suspense (impending man-made calamity), espionage (crimes against the state, which potentially have more victims than a single murder), and such sub-subgenres as police procedurals, historicals, humor, puzzles, private eyes, noir, and so on.

If you are expecting to read a bunch of what mostly passes for detective stories these days, you will be disappointed. Almost no one writes distinguished tales of ratiocination; observation of hidden clues and the deductions a brilliant detective makes of them is largely a lost art. Most contemporary detective stories rely on coincidence, luck, a confession, or flashes of insight by the detective (whether private eye, police officer, or an amateur who has taken time off from his or her primary occupation of cooking, gardening, knitting, writing, hair-dressing, or shopping).

Mystery fiction today is primarily devoted to the notion of “whydunit” rather than “howdunit” or “whodunit.” Therefore, most tales are based on psychological scrutiny, whether by a detective, by the reader, or by the protagonist.

The line between mystery fiction and literary fiction has become almost totally blurred. Such mystery writers as Elmore Leonard, Robert B. Parker, Dennis Lehane, George Pelecanos, James Ellroy, and others are certainly writing literary works. Such mainstream literary writers as Joyce Carol Oates, Michael Chabon, Paul Auster, Jonathan Lethem, Salman Rushdie, and others have written stories and books of mystery, crime, and suspense.

This collection is devoted to the best-written mystery stories published in the 2009 calendar year. You can call them mysteries or crime stories or literary stories, and you will be right. The goal, as it is every year (and this is the fourteenth edition), is to collect the very best mysteries of the year, and I think we have succeeded—again.

The “we” referred to above includes my colleague Michele Slung, who examines thousands of stories every year to find the most worthy; Nat Sobel, the greatest agent in the world, whose impeccable taste has discovered dozens of first-rate tales that have been recommended for inclusion; the scores of editors of literary journals who keep me on their subscription lists and often point out work that merits extra attention; and of course, Lee Child, the guest editor. It is a cause of astonishment as well as gratitude that Child, an author who hits number one on bestseller lists in America, England, and who knows where else, was willing to take time out from a very full schedule to read the fifty stories I selected as the best of the year (or, at least, my favorites) and pick the top twenty, as well as write a superb, thoughtful introduction.

Also important, if less directly, to the ongoing success of this series are the previous guest editors, who have generously lavished so much time and attention on these annual volumes: the late Robert B. Parker, Sue Grafton, Evan Hunter (Ed McBain), Donald E. West-lake, Lawrence Block, James Ellroy, Michael Connelly, Nelson De-Mille, Joyce Carol Oates, Scott Turow, Carl Hiaasen, George Pelecanos, and Jeffery Deaver.

While I engage in a nearly obsessive quest to locate and read every mystery/crime/suspense story published, I live in paranoid fear that I will miss a worthy story, so if you are an author, editor, or publisher, or care about one, please feel free to send a book, magazine, or tear sheet to me, c/o The Mysterious Bookshop, 58 Warren Street, New York, NY 10007. If it first appeared electronically, you must submit a hard copy. It is vital to include the author’s contact information. No unpublished material will be considered for what should be obvious reasons. No material will be returned. If you distrust the postal service, enclose a self-addressed, stamped postcard.

To be eligible, a story must have been written by an American or Canadian and first published in an American or Canadian publication in the calendar year 2010. The earlier in the year I receive the story, the more fondly I regard it. For reasons known only to the dimwits (no offense) who wait until Christmas week to submit a story published the previous spring, this happens every year, causing much gnashing of teeth as I read a stack of stories while my wife and friends are trimming the Christmas tree or otherwise celebrating the holiday season. It had better be an extraordinarily good story if you do this because I will start reading it with barely contained rage. Since there is necessarily a very tight production schedule for this book, the absolute firm deadline for a story to reach me is December 31. If the story arrives twenty-four hours later, it will not be read. Really.

O. P.

Introduction

EVERYONE SEEMS TO KNOW what a short story is, but there is very little in the way of theoretical discussion of the form. A tentative definition is often approached from two directions simultaneously: first, Edgar Allan Poe is quoted as being suspicious of the novel, preferring instead that which can be consumed at a single sitting; and then Mark Twain is quoted as saying — of a letter, not a story — “I’m sorry this is so long; I had no time to make it shorter.”

Some people attribute the second quotation to Pascal, but Twain is always a safe bet for quotes, and in either case the counterintuitive meaning is clear: it takes more time and greater effort to hone a narrative into a short form than to let it run a longer course. Combined with Poe’s concept of the “single sitting,” the short story is therefore seen as a delightfully well-crafted jewel, to be enjoyed by the connoisseur in the same way as a great meal or a glass of fine wine is enjoyed by a gourmet.

I’m not so sure.

To take issue with Poe first: his quote is full of self-interest. No one form has an inherent superiority over any other. All writers are scufflers at heart. We’re all trying to earn our daily bread, and we’ll do whatever sells. Poe’s “single-sitting-as-a-virtue” trope was driven by what the market wanted. He was trying to keep the wolf from the door by writing for periodicals, of which there was a huge and increasing number during his lifetime. Believe me, if he could have sold thousand-page novels, he would have, and today he would be remembered for extolling their manifest superiority over shorter fiction. But the market wanted bite-size pieces, so bite-size pieces were what he wrote. Charles Dickens was in the same boat, but Dickens just broke up his (thousand-page) novels into chunks, and they were printed sequentially, to great acclaim, not least because the desire to know what happened next proved so powerful. Arthur Conan Doyle was somewhere between the two; the Sherlock Holmes canon is certainly mainly a series of short stories, but “Sherlock Holmes” is also a single, massive entity, loved and enjoyed for its totality rather than its episodic nature, as if the whole arc exists independently of its disjointed publication history, as one giant mega-novel.

And to take issue with the assumption behind the Twain quote: I absolutely guarantee that none of the stories in this anthology took longer to write than their authors’ various novels. Not even remotely close. Yes, each sentence is crafted and polished; yes, each story was read and revised and then reread and revised again — but so is every sentence and chapter in a novel, and novels are much longer than short stories, and the effort expended is entirely proportional.

So, are the short stories in this collection not delightfully well-crafted jewels to be enjoyed by the connoisseur in the same way as a great meal or a glass of fine wine? Well, yes, they are, but not for the reasons given by conventional wisdom, but for a whole bunch of different reasons.

Short stories allow a little freedom. In their careers as novelists, the authors presented here are all, to some degree, locked into what they write, by economics and expectations. But in today’s market, short stories have neither a real economic upside or downside; nor are they constrained to any real degree by reader expectation. So authors can write about different things, and more especially they can write in different ways.

Novels are assembled like necklaces, from a long sequence of ideas that combine like gemstones and knots; short stories can contain only one idea. Novels must take aim at the center mass of their amalgam of issues; short stories can strike glancing blows, even to the point of defining the idea only by implication. (As in Ernest Hemingway’s famous six-word story: “For Sale. Baby Shoes. Never Worn.”) To some degree the slightness of — or the partial knowledge of — the central issue or idea becomes a virtue. For instance, I was once in an expensive boutique on Madison Avenue in New York City. It sold pens and notebooks and things like that. A woman asked to see some Filofaxes — small leather ring-binders designed for personal clerical use. She was shown two. She dialed her cell phone and said, “They have blue and green.” She listened to the reply and said, “I am not being passive-aggressive!”

Now, there is no way that eavesdropping incident could inspire a novel. There’s not enough there. But it could inspire a short story. Every writer has a mental file labeled “Great Ideas, Can’t Use Them in My Novels,” and short stories are where those ideas can find release.

Equally, every writer has mental files labeled “Great Voices, Can’t . . .” and “Great Characters, Can’t . . .” and “Great Scenarios, Can’t . . .” and so on. Noir writers might want to try a sweeter setup at some point, and “PG” writers might hanker after a real “R” rating — or even an “XXX.” The short story market is where those wings can be spread. The result is often a between-the-lines feeling of freshness, enthusiasm, experimentation, and enjoyment on the author’s part. That’s the feeling you’ll find in this collection, and perhaps that feeling brings us to a better definition of exactly what a short story is — in today’s culture, at least: short stories are a home run derby . . . the pressures of the long baseball season are put to one side, and everyone smiles and relaxes and swings for the fences.

LEE CHILD

G A R Y A L E X A N D E R

Charlie and the Pirates

FROMAlfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine

CALL HIM Juan Gama. That’s what he goes by. He isn’t Latino, but he’s dark, thanks to Syrian blood on his mother’s side. He can pass, at least with a nosy gringo tourist like this Charlie dude at the next table.

“Campeche has an amazing history,” Charlie Peashooter is saying, guidebook open beside his sweet roll and orange juice. “The only city in the Americas other than Cartagena, Colombia, to be walled to thwart pirates. You surely know that, señor. My apologies if I am boring you.”

Juan smiles blankly and nods, holding to the image that English to him is a foreign language. They are in La Parroquia, an open-air café on Calle 55. Morning eggs and coffee here is a homey routine Juan has fallen into. He knows that routines and patterns can be deadly, but six months in Campeche has slackened him.

Located on the Yucatán Gulf Coast, Campeche City is the size of Tacoma and Shreveport. It is tropical and picturesque, and nobody goes there. Juan Gama guesstimates a maximum of five hundred foreign visitors are in town at any one time, and that includes the Eurogringo variety. If they’ve determined that he fled south of the border, they would be scouring hot spots like Acapulco and Cancún, where one can debauch in style.

Juan Gama just turned twenty-four. Although he is nearly naked in shorts and T-shirt, he still manages to appear rumpled. His rimless glasses are smudged and his wavy black hair has a mind of its own. He is lanky and a bit awkward, and has accumulated fifteen pounds, much of it around the midsection. He hasn’t been so relaxed in years.

“Pirate,” he replies, pretending to struggle with the word.

“I should say so,” Charlie says, consulting his guidebook. “Listen to this. English, Dutch, and French pirates regularly plundered Campeche after its founding in the 1500s. On February 9, 1663, they combined forces and killed every man, woman, and child. After the attack, Spanish colonial authorities decided to wall the city. The project was completed over the following half-century and eliminated the pirate menace. Any subsequent foray was driven off.”

Not every woman was killed, not if you believe Teresa, Juan’s lady, who can get cuckoo on the subject. Teresa just knows that a female ancestor of hers survived, a beauty, ravaged by a pirate captain. She’s conflicted because of her pirate blood and what they did to her forebears.

Juan continues nodding, smiling.

Charlie initiated the conversation and introduced himself. He has a decade on Juan Gama. Slim and muscular and tanned, natty in slacks and pullover, his teeth are straight and white. The part in his sandy hair is as precise as a laser beam.

His appearance is agreeable and post-preppy, though his nose is too long and his features are too bunched to qualify him as Hollywood handsome. He smiles easily and his blue eyes never quite make contact. He is a baritone with perfect diction who wears heavy cologne.

Charlie has an aura of relentless congeniality. He looks to Juan like a game show host.

“Yes. Very hard times,” Juan says, returning to his eggs.

“Indeed. The definition of piracy is more varied and complex these days. One dictionary defines it as unauthorized use of another’s invention, production, or conception. They’re referring primarily to copyright infringement. Those software companies are having fits, aren’t they? Of course, the scope of piracy is even broader. For instance, the methodical manipulation of games of chance in three states. To the tune of two million dollars.”

Juan Gama drops his fork and looks up.

Charlie Peashooter’s smile is glorious. “Juan, you were thinking they would send a no-neck creature named Joe Knuckles?”

Juan Gama is genuinely speechless.

“Relax. That was the old way, in the old days. Please, finish your meal. Then we’ll talk.”

“I am a consultant,” Charlie explains as they stroll the malecon, the boulevard that skirts the Gulf of Mexico. “Understand this, Juan. I was sent to negotiate, to resolve this difficulty. I am a reasonable person. My employers are reasonable people. That is my context.”

They are walking beneath a fiery cloudless sky. The water is a vivid and murky green, like lime sherbet. “How’d you find me?”

“I’ll continue addressing you as Juan if you don’t mind.”

“I don’t.”

“You trained and operated a brigade of card counters on a scale heretofore unseen. You went on a whirlwind tour and made your money before the casinos realized what had happened. Were they frat rats from your college, old chums?”

“No. Dormies, some still in school,” Juan says.

“Compensation?”

“Fifty percent, less airfare and meals and hotel rooms.”

“Hit and run, you were. A veritable blitzkrieg. You trained and rotated them so fast they were long gone before their photos circulated. Your system was devastatingly simple and effective. Blackjack dealers who thought they’d seen everything never knew what hit them. Hats off to you, sir.”

“Uh, thanks. But, like, how’d you find me?”

“Resources. Everybody passed the hat and brainstormed. Your whereabouts was a challenge, sir.”

“Card counting isn’t a crime, you know. Having an idea what cards are left in the shoe shifts the advantage from the house to the player, that’s all.”

“It’s a question of ethics.”

Juan Gama laughs out loud.

“Oh, I admit it’s hypocritical, but that’s how it is. Nonetheless, my people want their money.”

Juan is on the verge of losing his breakfast. He pauses, takes a deep breath.

Charlie places a hand on his shoulder and smiles genially. “Juan, please do try to relax. It’s going to be all right. Bugsy and Moe and Icepick Willie haven’t inundated that environment for decades.”

Juan inwardly flinches. “You said negotiate?”

“That I did. The folks who run casinos nowadays have corporate bloodlines. They are cut from the entertainment conglomerates and tribal hierarchies. They understand that broken kneecaps don’t enhance the bottom line. They understand compromise, they understand business decisions.”

Juan nods grimly.

“A fifty-fifty split netted you in the neighborhood of one million smackeroos. You obviously live conservatively. Nevertheless, we wouldn’t expect you to have every last penny squirreled away.”

“You’re right.”

“We’ve written off your kiddy cohorts. I’m authorized to leave you ten percent free and clear. You give us ninety percent of the one million and keep the change. Down here, you’re set for life. They look at the swindle as tuition for the education you gave them. Whadduya say, guy?”

“Uh. Yeah. Okay.”

“When?”

Juan gazes out at the water. “Well, like I don’t have it in a suitcase under my bed.”

Charlie chuckles. “Ah. Offshore banks?”

“Grand Cayman,” Juan improvises.

“You were a statistics major before leaving academia without your degree, Juan. A brilliant albeit indifferent student. I’m pleased to be part of bringing peace of mind and stability to your life.”

“I appreciate that, Charlie.”

“When do you think?”

“Tomorrow maybe.”

“Let’s say tomorrow, definitely. Thanks to the miracle of electronics, we can do the transaction at the speed of light. All we require is the will. La Parroquia for breakfast. I’m buying.” Charlie gives him a slip of paper. “This is a wire transfer number. You say it’s done. I make a confirmation call. You live happily ever after.”

“Okay.”

Charlie gestures to the water. “Today’s the ninth of February. Quite a coincidence.”

“Huh?”

“The anniversary of the massacre, the ultimate plundering.” Charlie swings his arm inland, to the land gate, a man-made stone monolith. The attaching walls on this side are long gone. They are standing on land filled in the 1950s. “We’re at sea level. Before the fortifications, they simply moored and marched right in. No natural defenses. Tragic, tragic, tragic.”

Juan thinks of Teresa’s pirates. There must be a moral to Charlie’s story, but he doesn’t ask what it is.

“Translated, Juan Gama is Spanish for John Doe,” Charlie says. “Simplistic, yes, but you do have an engaging, impish quality.”

Juan replies by staring at his feet.

Charlie says, “Alas, we live in a grown-up world, Juan.”

Charlie sits on the edge of his bed. It is early evening, and he is watching the darkening horizon and the sea that is growing livelier by the minute. Charlie is five floors high, perhaps directly above where the pirates tied up. This hotel was the place to stay in Campeche during the go-go oil boom era, the late seventies and early eighties. Now it’s frayed, not entirely clean, and almost empty.

That’s just hunky-dory with Charlie. He doesn’t particularly like people and he enjoys the privacy.

He assembles his Colt .25 automatic, disassembles it, and repeats the process until the finest film of oil coats every moving surface. He wipes the excess and admires the machined creation that fits in the palm of his hand.

Smuggling the weapon into the country was no problema. Charlie’s clients flew him to Monterrey by private jet. From there he went charter to here.

He goes to the window and holds a round up to the fading light. In his home workshop, Charlie hollows his store-bought hollow-points until the lead walls are nearly translucent.

Nobody can operate at my proximity, he thinks proudly. Nobody. And he’s right. Charlie’s affability permits him point-blank range. Everybody likes Charlie. Not even the most paranoid assignment knows what hits him.

Cold steel against the ear. An instantaneous recognition of betrayal. One low-velocity shot, no louder than a handclap, the auditory canal serving as nature’s silencer. A gurgle, eyeballs rolling up like blinds, then nothingness. No muss, no fuss.

Medical examiners who have removed Charlie’s slugs from brains of assignments he has turned into porridge comment that they resemble spiders. This is only one component in the legend of Charlie Peashooter, who uses a sissy gun and never misses.

Charlie slips the Colt into a pocket holster, mesmerized by what has become a spectacular display of lightning and howling wind and horizontal rain. Palm trees are bent like bows and there are whitecaps on the hotel’s pool. He has never before been to the tropics and is amazed. The weather seems to be changing as fast as it does on the TV news where the talking haircuts speed up the satellite photos.

He worries about this Juan Gama assignment. His clients were so anxious that they dispatched him as soon as they isolated Juan and his breakfast ritual. Charlie hasn’t the foggiest where Juan lives, though they did discover that he resides in the area with a woman named Teresa and her brother Perez.

Juan is a flighty young man who lacks graces. But he seems sensible. He should show tomorrow. After Juan Gama provides the magic number and the transaction is accomplished, Charlie will steer him someplace where he can complete his assignment. It isn’t, after all, all about money. It’s the principle of the thing.

Charlie shuts off the light. Early to bed, early to rise. That’s his motto.

He stares at the flyspecked ceiling, again finding it peculiar that his clients often prioritize retribution above financial recovery. He puzzles over them as he does serial killers. He’s never understood the breed. Why not kill for fun and profit?

He yawns, deciding that it takes all kinds.

Juan Gama stares at a ceiling that is not flyspecked. Teresa is an immaculate housekeeper.

“Your trouble, has it come for you?”

“Why do you say that?”

“How you were when you come home late from breakfast.” Teresa hesitates. “How you are now, how you hold me after we make love tonight. You never hold me afterward.”

Teresa is older than Juan. She is a kind, passionate woman with glossy black hair and trusting eyes. She has ample hips and comes up to his shoulders. She works as a travel agent at the hotels. Juan and she met on a day trip she led to the Maya ruin of Edzna. Juan was the odd man out in a group of French tourists.

Juan took her to dinner afterward. They ate broiled grouper and drank wine. They drank more wine and held hands. Teresa said he looked like he was lost. Not any longer, he said.

Teresa took Juan to her home in the old walled city. He has been there ever since, sharing the house with her worthless brother, Perez, who is his age. Teresa is lover, mother, and best friend to him, all that and more.

The walled city is in the throes of urban renewal. Lining narrow streets of flat, smooth blocks are row upon row of one- and two-story dwellings with ornate doors, wrought-iron balconies, and pastel stucco. Those that aren’t already spiffed up are getting the treatment, buckets of paint dangling from precarious bamboo scaffolding. The town’s being daubed in every jelly bean color except licorice.

Teresa’s is tangerine. Her front room is a mini-museum. Descended from a longtime Campechano family — some great-great-greats of hers helped fight off the pirates, so she claims — she has old-timey portraits of them and bad dudes like Pegleg Pete and Blackbeard. In an armoire and mounted on a wall are a flintlock pistol, a cannonball, a blunderbuss, and a crossbow.

A gust from the storm has the wooden shutters clattering like drumsticks. Juan gets out of bed and secures them.

“I felt you were running from something, but you would never confide in me.”

She is on her side, her back to him.

“I don’t want to burden you,” he says, not completely lying.

“You can, Juan.”

“It’ll be fine.”

“Your name. Juan Gama. I know it is not real.”

“Would you like my real —”

“No. I want to know you as I know you.”

Juan Gama–John Doe, he thinks. He must have been out of his mind. Totally clueless. But he has gone through life treating life like a game.

He thinks she is asleep when she asks, “Have you seen Perez today?”

“No,” he lies.

“I did not hear him come in. El Norte, this awful storm, I hope he is not caught in it.”

Northers, the winter storms that occasionally blast through, the locals call them El Norte. “He’ll be okay. He’s a big boy.”

“He is not a big boy, Juan. He is a child.”

Juan pretends that he is dropping off.

“Sometimes, Juan, you remind me of Perez.”

Juan does not drop off. He does not sleep a wink. He knows that as good a dude as Charlie seems to be, there are limits to his good nature.

If only I had money to give him, Juan laments.

Charlie Peashooter sips coffee at La Parroquia well past Juan Gama’s breakfast time. He is disappointed in Juan, although not surprised. He cannot imagine greed clouding one’s survival instincts, but that’s human nature.

The storm has abated slightly. It is no longer curling eyelids inside out and raising tsunamis on mud puddles. It is not ideal flying weather. However, this is a blessing. Charlie overhears a taxi driver at the next table complaining to a waiter that nothing is landing at the airport because of high crosswinds and water on the runway.

The airport, Charlie thinks. On a hunch, he asks a waiter where Juan is and learns that Juan had told him that he was flying out of town this morning for a short trip.

Perez gazes out rain-streaked glass at the airstrip. A plane accelerates along the runway, its tires raising roostertails. It lifts off the ground just fine. His airliner from Mexico City could lift off just fine too to fly him to the capital on its return flight, but it isn’t here. You can take off in this stuff, but you cannot land, so it has been diverted.

Perez doesn’t understand flying, how you can go up but not down in foul weather. He orders another glass of whiskey from the bar. It would be just his luck if El Norte pours and blows for the three solid days. He feels at times like a big, black cloud hovers above him.

The gringo, his sister’s boyfriend, who has never offered him a peso, had given him an airline ticket to cash in and meals and barhopping and a hotel room he had reserved in Mexico City. The gringo said he had business that was canceled, so why waste the trip?

The gringo has no business that Perez knows of and has not gone anywhere since he moved into Teresa’s bed, but Perez did not argue with him.

Perez drinks and he smiles. He suspects that Teresa is behind this. She wants her brother out of the way for a few days so she can be alone with the gringo and extract a marriage proposal. While Juan isn’t a terrible fellow for an Anglo, Teresa seems to like him more than he likes her.

Whether Juan stays or he goes, Perez has no strong opinion. He is rich like any gringo is rich, but no big money has materialized until this travel gift. The home belongs to Perez also and Teresa is a hard worker. Due to a combination of bad luck and bad bosses, Perez has had no success holding a job, but thanks to Teresa, there will always be beans and tortillas on the table.

“Are we in for forty days and forty nights of this? If you see a boat floating by loaded with animals, head for the hills.”

Perez laughs at the corny joke by the gringo with the broken Spanish who is standing beside him.

“Of all the rotten luck,” the gringo goes on. “My girlfriend is waiting at the Mexico City airport for me.”

“Man, I know what you mean about bad luck,” Perez says.

“Two weeks in Campeche on a consultancy assignment, she is as ready to see me as I am her. If you catch my drift.”

Perez catches his drift. He is smiling broadly and winking. He is so suave and his voice is so perfect he should be a master of ceremonies on American television.

“You got my sympathy, man. I was going there on holiday. If you got money and I got money, you can find yourself a party anywhere.”

The gringo sighs. “Too bad about our plane. My girl’s sister is visiting us. She’s your age and is hot as a firecracker.”

Perez looks at him.

The gringo makes an hourglass gesture with his hands. Perez resumes observing airplanes spray water as they taxi. His last job was peddling wooden pirate ships on the street to tourists who did not want to buy them. Now that he finally has a wad of pesos in his wallet, the fates are depriving him of his fun.

The gringo snaps his fingers. “I have an idea. They say Mérida is clearing up. There must be outgoing flights. How far is it?”

Mérida, capital of Yucatán State, is an easy three-hour drive. Perez answers him and adds, “On account of the weather, it could take longer, but not much.”

“I have a car, but I don’t know the roads.”

“I know the roads,” Perez says.

“You’d be doing me a favor, taking the sister off my hands. You strike me as being capable of pulling that duty.”

Another grin and wink. He is a nice, friendly man and they have a mutual problem.

“Why not?” Perez says. “What do I have to lose?”

Next day, Sunday, is as bright and hot as Juan Gama’s mood is cool and gloomy. Teresa suggests that they take food and drink to the central plaza. There is a concert and big crowds. They can watch the people and listen to the music.

“You are troubled with the demons in your head and I worry about Perez. It will take our minds off these things,” she says.

Juan shrugs. “He met a woman. That’s all.”

“He packed clothes before he went out yesterday and did not say a word to me.”

“He’s a grown man, Teresa.”

“Only in years.”

Juan lets it ride. Despite his offer to buy their food and drink from vendors, frugal Teresa packs bread, cheese, and sodas. For the eight blocks to the plaza, he carries their picnic sack in one hand and holds hers with his other. Since this is the end of him and her, this moment is incredibly bittersweet.

Juan is certain that Perez is in Mexico City, eating and drinking and living it up. When he stood Charlie up at La Parroquia, there were bound to be repercussions. Juan pictures Charlie beelining it to the airport to cajole Juan Gama’s Mexico City itinerary from airline people.

If Charlie knew where he lived, he’d’ve come for him at Teresa’s, not the café. Juan estimates that he has a one-day window to escape. Today.

On a bench in the plaza, he looks at the people and the band. He sees and hears nothing. His thoughts wander to roulette, the purest of the casino games.

The wheel itself, rich inlaid wood, spinning on precision bearings, is a work of beauty. At rest or in motion, it is mesmerizing. No participation whatsoever is required of the player. You lay your money on the felt and the dealer rakes it off.

Juan Gama, a statistics major with a mathematical brain; of all people, he should have known better. He could not stop himself any more than a heroin addict could keep a needle out of his arm. Like one of those degenerate gamblers, he lost the card-counting proceeds almost as fast as they came in.

He has enough money stashed for another year. Then what? He can worry about that then. Charlie is today’s headache.

Easygoing Charlie, wouldn’t he sympathize if Juan could convince him of his staggering roulette losses? What is that old saying? You’re only a temporary custodian of the house’s money. Wouldn’t Charlie take back word to his bosses that they’ve had their money all along?

Yeah, right. And pigs can fly.

“Are you not feeling well?” Teresa asks.

“What?”

“You won’t talk to me. You have been in a trance.”

“Sorry.”

She gets up. “Since you are not having any fun, I cannot have any either. Anyway, I am anxious to see if Perez is home.”

Why not? Juan thinks, rising slowly. He puts his arm around her and, setting a slow pace, begins to tell her everything.

Charlie Peashooter is impressed. This little abode is as neat as a pin and the living room is an antique store with a military theme, including a rogue’s gallery of buccaneer and colonial potentate portraiture. The feminine touch is apparent, with doilies and the scent of waxes. The decorator presumably is the sister of that unfortunate lad with the drinking problem.

In order to gain access to the airport terminal’s interior, Charlie had purchased a ticket to Cancún. When he did not see Juan, it was logical that he utilized someone in this misdirection play. Another element in the logic: why would Juan blab to that waiter if he was skipping town? It had been easy enough to grease a ticket agent’s palm to learn if a man named Perez had likewise purchased a ticket and to identify him.

Juan Gama’s ill-gotten gains may not be in an offshore account, Charlie theorizes. Perhaps, he thinks, Juan is old-fashioned, preferring to squirrel it in a mattress. His guess is close. In a shoebox in a cubbyhole behind a closet, perhaps unbeknownst to the lady of the house, is a shoebox containing fifteen thousand dollars in green-backs and pesos.

Juan is teasing him with petty cash. They will have their chitchat concerning that Grand Cayman numbered account.

Charlie peeks between curtains. The stinker, there he is, home early from their picnic. His pleasantly plump lady friend is red-eyed, squeezing her hankie for all it’s worth. Charlie steps out of the light.

“How could you do this to Perez?” a sniffling Teresa is saying not for the first time. “To make a hunting decoy of him.”

“Hey, like he’s having a ball,” Juan says. “Charlie’s looking for me, not Perez. Nothing will happen to him.”

“Something already has. I can feel it. How could you lie to me for these months?”

“I wasn’t lying. I, uh, withheld. I was planning to tell you everything soon.”

“Liar. When are you leaving me?”

“I have to go right away. I’ll be back as soon as I can. I promise.”

“Liar. What do I smell?”

They are inside. Juan is about to close the door, but he freezes. He smells it too.

“A man’s perfume. You do not wear any.”

“I do,” Charlie says, stepping out of a shadow. “Forgive me. The door was unlocked.”

“Liar,” Teresa says, backing into Juan.

Juan steps protectively in front of her. “Charlie, I need an extra day or two.”

Charlie sighs and exhibits a compassionate frown. “Juan, Juan, Juan. You should have been upfront. That hurts. I’d’ve worked with you.”

Juan hangs his head.

Teresa demands, “Where is my brother?”

“A fine young man. Dissipating himself in Mexico City, I’ll betcha. Oops, sorry, sis,” Charlie replies with a wink.

“Liar. Liars. Both of you.”

Charlie looks at Juan, his eyes widening playfully. “Well, I know where the term ‘Mexican spitfire’ originates, you lucky dog. Juan, now, this situation of ours?”

“One more day, Charlie. There’s a mix-up on the account numbers —”

“You stop lying to him, maybe he will stop lying to me.”

“Excuse me?” Charlie says to her.

Teresa looks at Charlie and his dead, cordial eyes. She has no expectation of prizes behind curtains.

“There is not any money except for what this man hides in my house he thinks I do not know about. Answer me where my brother is and you can take that money and go.”

“No money?” Charlie says to him. “There has to be money.”

“There is. Honestly, Charlie, there is.”

Juan says “honestly” as car dealers in TV commercials do. Charlie realizes now that there is no money. An unsatisfactory development, yes, but the denouement will be the same.

He sidles to Juan, pats his arm, and says, “Money. If you say so. Splendid. Heck, we should go out to a telephone right now and resolve this. Let’s get it out of our hair, okay?”

Juan’s feet won’t move.

Charlie gives him a winning smile and a nudge that is more than a nudge. “C’mon, big guy, one call does it all.”

“No,” Teresa says in a hoarse whisper.

But she is not speaking from where she was, behind Juan’s slumped shoulders. She has shifted to the hallway shadows. He may have to do her also. Three assignments for the price of one. Life is so unfair.

He has already edged Juan outside. Hand firmly clamped to a wrist of his prey, Charlie reenters. He blinks, eyes adjusting to the darkness, and turns toward Teresa, igniting his smile. He glances at the wall with the pirate memorabilia. Something is missing.

Charlie reaches into his pocket when it dawns on him what it is. He reaches too late. The arrow pierces his throat as he draws his pistol.

“We drove your kind away once. We can do it again,” Teresa says.

She is not talking to Charlie Peashooter, who is on the floor and cannot hear her. She is talking to Juan, who stumbles out the door and breaks into a run as she reloads the crossbow.

R . A . A L L E N

The Emerald Coast

FROMThe Literary Review

THERE WAS NO BREEZE. The Gulf’s blue-green surface was flat, and a haze — the waning vestige of a morning fog — hung above it. Listless waves slopped the tide line like a careless janitor. Waitron lit a cigarette and half-leaned half-sat on the wooden railing that enclosed the al fresco deck of Joe’s Crab Trap. It was the midafter-noon lull: bartenders prepping fruit garnishes for happy hour, busboys sweeping up sandy French fries, and the wait staff trudging through the personally unprofitable side work demanded by management in order to save money by not actually hiring someone to clean mirrors, dust woodwork, polish stainless steel, and whatnot.

Because of the haze, the glare was diffuse and everywhere and it burned into Waitron’s retinae even in the shade of the deck’s canopy. The haze muffled the beach noises: children squealing, the thump of a volleyball, snatches of music, the shrieks of gulls. He scanned the long white shore from east to west for as far as he could see. How many females could he discern between the vanishing points of his sight? Three hundred? More than five hundred? Certainly less than there were in August.

The need within him was rising, building like steam, his need for sex-plus. Sex-plus was a fulfillment that, he knew, average men never dream of; but it was his ultimate gratification. It came at a price, though, and the price was the need itself — the wanting — which was like hunger and thirst and a drug craving rolled into one. It was time to mark this territory and move on. He was first out in the shift rotation tonight and would be packed up and headed for Colorado in a few days, disappearing back into the floating world of the seasonal waiter. The time was right, like planets aligning in his favor. He would have to find the right one. He would try tonight.

“Robert?”

It would be Holcomb, the day-shift manager; the only one who addressed him by his real name. Hands on hips, Holcomb was standing just inside the doorway. He said, “You think you might dust the paddle fans anytime soon?”

Because he was tall, this was one of Waitron’s side-work duties. He dead-eyed Holcomb for a beat or two. “When I finish this,” he said, ashing his cigarette on the plank floor.

Holcomb went back inside.

There was nothing else Holcomb could say and they both knew it — the season was ending. Waitron turned his attentions back to the beach. How many between the ages of twelve and twenty-four? How many with the correct hair? The right body?

Now a hammering noise broke his reverie — a man replacing shingles atop the main building of the restaurant. Waitron watched him with detachment. The roofer was one of those construction worker types that, a few seasons ago, were everywhere in Destin. Scruffy hair and beard, shirtless and tanned impossibly dark, one of the numberless rabble drawn from the rural areas of the Southeast by the building boom now fizzling out along the Emerald Coast of the Florida Panhandle. He was just under medium-sized, monkey-built, a creature of sinew and vein. He wore a tool belt over cutoff jeans and a pair of filthy tennis shoes. To Waitron, he was a perfect specimen of his class: a cracker, a variety of Georgia/ northern-Florida white trash whose life revolved around semi-skilled labor, cheap beer, and trailer park squabbles. It must be 120 degrees up there, Waitron mused — how does he stand it?

As if he could feel someone staring, the roofer stopped work and eased into a squatting position against the low slope of the roof, forearms resting on his knees, hammer dangling from one hand. He stared back at Waitron. The roofer had a crude tattoo — an eye — on his left triceps. A warning floated up from Waitron’s memory. The roofer continued to stare at him with pale eyes set in a hawkish face. Waitron turned away.

Oakley paced the balcony, grinding on the mood he was in. “They call us trailer trash,” he said. “And because the world has tarred us with this appellation, we are condemned to a brutish existence.”

“I reckon what we’re called is an accident of our births,” Sparrow responded mildly. “I don’t feel like trash.” He’d been pounding nails since five a.m. in the broiling heat. Now freshly showered and in clean clothing, all he wanted was to relax with this beer while the sun set on the beautiful Gulf below. “You read some Hobbes when you were up in Fountain?”

“Yeah, I read Leviathan. I read that copy of The Peloponnesian War you sent. I read a lot. Ain’t nothing changed: you do your forty-cent-an-hour job, you do your reps at the weight pile, you go to chow when they call you, and you sleep when it’s lights out. There’s still lotsa time left over to advance your education.”

“You didn’t go Mao-Marxist on me did you?” Sparrow joked.

“Nah. I’m just saying . . .”

Oakley had been out for three weeks. His doomed fascination with a jewelry store up in Dothan had bought him a stretch of two years and ten months.

Sparrow and Oakley had been best friends since grade school in a nameless, sun-struck tract of Section Eight housing on the outskirts of Mary Esther, Florida — itself a strip mall of a town that owed its existence to neighboring Eglin Air Force Base. They had shared the highs as well as the misery, looking out for each other in stir and out.

They were on the balcony of Oakley’s second-floor crash in the old Spindrift Motel, a fifties-era relic, now condemned — pilings washed out by a June hurricane had destabilized the western wing. By this time next year, the pastel high-rise depicted on the billboard out front would take its place. Oakley was living there on the sly through the beneficence of Two-Eleven, the Spindrift’s onetime handyman, now caretaker-cum-watchman pro tem and old jailing buddy to them both. It was no big deal to Two-Eleven, as he figured to be let go when the developer sent the dozers in — which might be any day now.

With two hundred feet of sand-covered extension cord, Oakley was stealing enough electricity from the absentee owners of the condo next door to power a refrigerator, a fifteen-gallon hot water heater, and a couple of lamps. There was no A/C, but it was late September, so the heat was tolerable for sleeping — just. Money for the necessities came in from day trips as a deckhand on the charter boats out of East Pass, baiting hooks for tourists, cleaning their catches, swabbing the decks and gunnels, lugging ice — the flunky work of a nautical factotum. But Oakley, not one to take direction in the first place and chafing at the dictatorial manner of the charter captains, was gaining a reputation as a malcontent on the marina. His other source of income, he’d told Sparrow, was “odd jobs.”

They watched a young couple stroll out to the water’s edge and settle onto a blanket. For Sparrow, the girl added a carload of black chips to the quality of the beachscape. She was a stunner, a corn-silk blonde not older than twenty. In defiance of a municipal ordinance laid down by the local guardians of social order, she was wearing a thong — coral in hue, a mere afterthought in terms of beachwear. Sparrow shivered. “You get laid since you got out?”

“Went and saw Amber a couple of times while that sheriff’s deputy she moved in with was on duty, but she’s turning into a candidate for Girls Gone Wild.”

Sparrow remembered the hot-and-haughty Amber. He emitted a dry laugh.

Oakley studied the thong girl for a moment and then looked away, as if the sight of her caused him pain. “I got money on my mind, bro. I lack funding. A man can’t be who he really is without money. Which brings up my next point: I need to find Davy Redstone.”

“Davy Redstone the fence?”

“Yeah. He owes me three dimes from that pawnshop B-and-E that I pulled before I went in. I heard he’s hanging out at a bar north of the 331 Bridge, a slop chute called the Owl’s Eye. I need you to go with me. I need you to watch my back.”

“That was four years ago. Redstone’s gonna balk on you.”

“I will stress to him that a debt is a debt. He gives me any shit, I’ll have to tune him up.”

Sparrow nodded. He did not doubt that the prospects for violencia were distinct, if not imminent. Along with the alpha-dog precepts of your seasoned convict, Oakley had the muscle and the martial portfolio to back up a volatile nature. Problem was: Redstone traveled with an entourage. If it came to a dustup, they would be bucking the law of superior numbers.

“He’ll have his homies cheek by jowl,” Sparrow said.

“I got no choice.”

“I’m there for you, bro.”

Watch my back was the undeniable — the unquestionable — call for support between them. And Sparrow’s response was gold-standard true, true at the risk of incarceration, true past the point of injury, true unto death. It was his duty to a bond forged out of old hard times.

Duty. At one time, Sparrow would have greeted violent confrontation in service of this bond with gritty cheer. But he had turned thirty-three in March. Somewhere, Sparrow had read that thirty-three is an introspective watershed for even the thickest of men: they come to the sit-up-in-bed realization that times are flying. Like the tolling of a giant bell, it had been no different for him. He had been into some kind of criminality since the age of twelve — all of it larcenous, some of it violent, most of it with Oakley. But during his latest left-handed endeavor, Oakley had been behind bars. It was in collusion with an Atlanta-based counterfeiter — a former penitentiary colleague — that Sparrow spent two months passing bogus twenties in the Caribbean. The Feds were waiting for him at the gate at Miami International. On a half-dozen surveillance videos, he starred as the prosecution’s witness against himself.

The government confiscated everything they could find; what they couldn’t find, his lawyer wound up with. He’d bargained for thirty months and maxed it out at the Federal Correctional Institution in Marianna. It wasn’t that he couldn’t do the time; it was just that, in the joint, the judicial system is eating the front end off of your future.

Right after his release, he’d met, fallen in love, and moved in with Marlene, a clerical for a bail bondsman in Fort Walton. She had a four-year-old daughter who adored him for no reason whatsoever. So he had come to a conclusion: he didn’t care if he had to be a roofer or a ditch digger or a dishwasher for the rest of his life, he wasn’t going to do any more time. He had a duty to Marlene. And for little Jonquil, he was going to be the father she’d never known. Would Oakley understand his duty to them? Sparrow didn’t think so. Right now, he wished he were at home with them, watching TV. But Marlene was up in Waycross visiting her mama, which was why he now found himself here with Oakley. He hoped they wouldn’t find Redstone.

“When do you want to go?” Sparrow said.

“Now.”

“My truck is on empty.”

“We’ll take my car.”

“When did you get a car?”

“The other day. It’s parked over in the Hampton lot. Keeping it around here might draw attention to my living arrangements. Grab the rest of them beers. Let’s go.”

Sparrow gave the beach a wistful last look. The wind was picking up.

The Hampton Inn was a two-block walk east on Scenic 98 — the original beach-view part of Highway 98 — and two blocks north. There was no view of the Gulf from this Hampton, and it attracted the folks that couldn’t afford one — kids, mostly, or blue-collar families who scrimped to give their children a few days at the beach. From the rooftops, Sparrow would see them: mom, dad, and their youngsters, shuffling along in single file — serious as mourners — on the white gravel shoulders of the beach-access streets, wearing their sandals and bathing suits, loaded down with towels, coolers, floats, umbrellas, and other beach crap.

Oakley’s ride was a late model Taurus. Sparrow got in and took its measure. “You boosted a rental,” he said, checking the column.

“Yeah. But the plates are fresh.”

“Goddamn.”

Oakley was grinning like a dog eating cheese. “Don’t worry, bro. I’ll drive safe.”

“Hi, folks, I’ll be your waitron for your dining experience tonight,” he said — his standard icebreaker that generally evoked a smile from patrons. “Would you like to start with a cocktail?”

The party was comprised of two fortyish couples and a teenaged girl — a daughter, he supposed. The adults wanted cocktails. While they decided, Waitron eyed the girl. Her hair was all wrong — too long, too light.

Leaving with their drink order, he noticed a lone girl at the bar. She was correct: petite, shoulder-length brunette hair, early twenties. Her face was okay — a poor man’s Drew Barrymore. The glasses were an added attraction. By coming in here with that sluttish haircut, she was begging for sex-plus.

This was his last table. If the girl at the bar stayed until his checkout was over, it would be another sign.

She reminded him of number four, decomposing now for some two years in a hole fifty yards into a wooded area off of Highway 7 a few miles outside of Norwalk, Connecticut. Like the others, he had her GPS coordinates committed to memory: bargaining chips that would keep him off death row in case they caught him.

The sun went down. His table decided against dessert, but, to his annoyance, one of the women wanted coffee. He checked on the girl at the bar. She’d just ordered another margarita. His luck was holding.

After Waitron finished with his checkout, he marked time at the waiter’s station, rolling silverware in paper napkins and watching the girl. Finally she finished her drink and paid, leaving, not by the door to the lot that bordered Scenic 98, but down the steps to the beach. Perfect. Waitron felt his nostrils flare; felt his lungs fill to the bursting point. He counted to ten and exited by the front door. He jogged through the parking lot to his car, where he grabbed the sack that contained the things he needed and then walked around the outside of the building to the beach. Her white shorts made her easy to follow as she walked eastward, barefoot in the surf-dampened sand.

Oakley had the pedal flat on the floor on their way back across Choctawhatchee Bay, speedometer bumping 110. The Taurus was bucking like a jackhammer because, having whacked a parked truck on their gravel-slurring escape from the Owl’s Eye, the front end was out of alignment.

“Feels like we’re coming apart,” said Sparrow, gripping the arm-rest.

“We gotta get off this bridge,” Oakley said. “If they called the five-o’s, we could get bottled up.”

Sparrow thought his prayers had been answered when they walked into the Owl’s Eye to find that the fence was not there. They’d hung around for a while at the bar, casually pumping an evasive bartender about Redstone, and otherwise minding their own business.

Evening dissolved into night. The Owl’s Eye was a dive and it possessed that seething atmosphere that all dives have, but things remained peaceful until a girl who was all teased-up hair and quick movements came up and wanted to know about Oakley’s shamrock tattoo like it was some kind of message aimed at her from outer space.

Turns out: there was a narrow-minded boyfriend.

Oakley knocks boyfriend’s eye out of its socket with a backhanded blow from a two-pound beer mug.

Boyfriend’s friends materialize.