20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

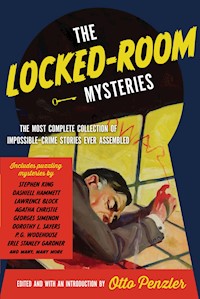

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

In this definitive collection, Edgar Award-winning editor Otto Penzler selects a multifarious mix from across the entire history of the locked room story, which should form the cornerstone of any crime reader's library. Virtually all of the great writers of detective fiction have produced masterpieces in this genre, including Agatha Christie, Edgar Allan Poe, Dorothy L. Sayers, Arthur Conan Doyle, Raymond Chandler, G.K. Chesterton, John Dickson Carr, Dashiell Hammett, Ngaio Marsh and Stephen King. The purest kind of detective story involves a crime solved by observation and deduction, rather than luck, coincidence or confession. The supreme form of detection involves the explanation of an impossible crime, whether the sort of vanishing act that would make Houdini proud, a murder that leaves no visible trace, or the most unlikely villain imaginable. 70 stories handpicked by Otto Penzle

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

ALSO EDITED BY OTTO PENZLER

The Big Book of Christmas MysteriesThe Big Book of Ghost StoriesZombies! Zombies! Zombies!The Big Book of Adventure StoriesThe Vampire ArchivesAgents of TreacheryBloodsuckersFangsCoffinsThe Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask StoriesThe Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps

First published in the United States in 2014 by Vintage Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

Published in e-book in 2014 and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2015 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Introduction and compilation copyright © Otto Penzler, 2014

The moral right of Otto Penzler to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

The permissions to reprint previously published material appear on pages 939–41.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 0 857 89892 0E-book ISBN: 978 1 782 39029 9

Printed in Great Britain.

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Anthony CheethamGentleman, scholar, loyal friend

CONTENTS

Introduction by Otto Penzler

FAMILIAR AS THE ROSE IN SPRING

(The most popular and frequently reprinted impossible-crime stories of all time.)

THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE Edgar Allan Poe

THE PROBLEM OF CELL 13 Jacques Futrelle

A TERRIBLY STRANGE BED Wilkie Collins

THE TWO BOTTLES OF RELISH Lord Dunsany

THE INVISIBLE MAN G. K. Chesterton

THE DOOMDORF MYSTERY Melville Davisson Post

THE ADVENTURE OF THE SPECKLED BAND Arthur Conan Doyle

THIS WAS THE UNKINDEST CUT OF ALL

(Stabbing in a completely sealed environment appears to be the most common murder method.)

THE WRONG PROBLEM John Dickson Carr

THE THING INVISIBLE William Hope Hodgson

DEPARTMENT OF IMPOSSIBLE CRIMES James Yaffe

THE ALUMINIUM DAGGER R. Austin Freeman

THE CREWEL NEEDLE Gerald Kersh

THE DOCTOR’S CASE Stephen King

A KNIFE BETWEEN BROTHERS Manly Wade Wellman

THE GLASS GRAVESTONE Joseph Commings

THE TEA LEAF Edgar Jepson & Robert Eustace

THE FLUNG-BACK LID Peter Godfrey

THE CROOKED PICTURE John Lutz

BLIND MAN’S HOOD Carter Dickson

FOOTPRINTS IN THE SANDS OF TIME

(Is there a more baffing scenario than to find a body in smooth sand or snow with no footprints leading to or from the victim?)

THE MAN FROM NOWHERE Edward D. Hoch

THE LAUGHING BUTCHER Fredric Brown

THE SANDS OF THYME Michael Innes

THE FLYING DEATH Samuel Hopkins Adams

THE FLYING CORPSE A. E. Martin

THE FLYING HAT Vincent Cornier

AND WE MISSED IT, LOST FOREVER

(It is a fantasy for many people to disappear from their present lives. Some people disappear because they want to; others disappear because someone else wants them to. And objects—large objects—sometimes disappear in the same manner.)

THE DAY THE CHILDREN VANISHED Hugh Pentecost

THE TWELFTH STATUE Stanley Ellin

ALL AT ONCE, NO ALICE William Irish

BEWARE OF THE TRAINS Edmund Crispin

THE LOCKED BATHROOM H. R. F. Keating

MIKE, ALEC, AND RUFUS Dashiell Hammett

THE EPISODE OF THE TORMENT IV C. Daly King

GREAVES’ DISAPPEARANCE Julian Hawthorne

THE HOUSE OF HAUNTS Ellery Queen

THE MONKEY TRICK J. E. Gurdon

THE ORDINARY HAIRPINS E. C. Bentley

THE PHANTOM MOTOR Jacques Futrelle

THE THEFT OF THE BERMUDA PENNY Edward D. Hoch

ROOM NUMBER 23 Judson Philips

HOW EASILY IS MURDER DISCOVERED

(There are so many ways for the creative killer to accomplish the act.)

THE BURGLAR WHO SMELLED SMOKE Lynne Wood Block & Lawrence Block

THE KESTAR DIAMOND CASE Augustus Muir

THE ODOUR OF SANCTITY Kate Ellis

THE PROBLEM OF THE OLD OAK TREE Edward D. Hoch

THE INVISIBLE WEAPON Nicholas Olde

THE CONFESSION OF ROSA VITELLI Ray Cummings

THE LOCKED ROOM TO END LOCKED ROOMS Stephen Barr

SHOOT IF YOU MUST

(It may not be terribly original, but shooting someone tends to be pretty effective.)

NOTHING IS IMPOSSIBLE Clayton Rawson

WHERE HAVE YOU GONE, SAM SPADE? Bill Pronzini

IN A TELEPHONE CABINET G. D. H. Cole & M. I. Cole

DEATH OUT OF THIN AIR Stuart Towne

THE DREAM Agatha Christie

THE BORDER-LINE CASE Margery Allingham

THE BRADMOOR MURDER Melville Davisson Post

THE MAN WHO LIKED TOYS Leslie Charteris

THE ASHCOMB POOR CASE Hulbert Footner

THE LITTLE HOUSE AT CROIX-ROUSSE Georges Simenon

STOLEN SWEETS ARE BEST

(How does a thief remove valuables from a closely guarded room? It seems impossible, but . . .)

THE BIRD IN THE HAND Erle Stanley Gardner

THE GULVERBURY DIAMONDS David Durham

THE FIFTH TUBE Frederick Irving Anderson

THE STRANGE CASE OF STEINKELWINTZ MacKinlay Kantor

ARSÈNE LUPIN IN PRISON Maurice Leblanc

THE MYSTERY OF THE STRONG ROOM L. T. Meade & Robert Eustace

NO WAY OUT Dennis Lynds

THE EPISODE OF THE CODEX’ CURSE C. Daly King

ONE MAN’S POISON, SIGNOR, IS ANOTHER’S MEAT

(Often described as a woman’s murder weapon, poison doesn’t really care who administers it.)

THE POISONED DOW ’08 Dorothy L. Sayers

A TRAVELLER’S TALE Margaret Frazer

DEATH AT THE EXCELSIOR P. G. Wodehouse

OUR FINAL HOPE IS FLAT DESPAIR

(Some stories simply can’t be categorized.)

WAITING FOR GODSTOW Martin Edwards

INTRODUCTION

OTTO PENZLER

AMONG AFICIONADOS of detective fiction, the term “locked-room mystery” has become an inaccurate but useful catchall phrase meaning the telling of a crime that appears to be impossible. The story does not require a hermetically sealed chamber so much as a location with an utterly inaccessible murder victim. A bludgeoned, stabbed, or strangled body in the center of pristine snow or sand is just as baffling as a lone figure on a boat at sea or aboard a solo airplane or in the classic locked room.

Like so much else in the world of mystery fiction, readers are indebted to Edgar Allan Poe for the invention of the locked-room mystery, which happened to be the startling core of the first pure detective story ever written, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” initially published in the April 1841 issue of Graham’s Magazine. In this groundbreaking tale, two women are heard to be screaming and a group of neighbors race up the stairs to the women’s apartment. They break down the locked door, the key still in the lock on the inside, to find the savagely murdered mother and daughter. The windows are closed and fastened, egress through the fireplace chimney is impassable, and there are no loose floorboards or secret passages. Of course, the police are baffled (just as readers were then, and continue to be today, one hundred seventy years after the story’s original appearance). Only the detective, C. Auguste Dupin, sees the solution, establishing another of the mainstays of the detective story: the brilliant amateur (often replaced in later stories by the private eye) who is smarter than both the criminal and the official police.

The locked-room mystery, or impossible-crime story, is the ultimate manifestation of the cerebral detective story. It fascinates the reader in precisely the same way that a magician is able to bring wonderment to his audience. What he demonstrates appears to be impossible. After all, young ladies, no matter how attractive and scantily clad, don’t just disappear, or turn into tigers, or get sawed in half. Yet we have just seen it happen, right before our very focused eyes.

Be warned. As you read these astoundingly inventive stories, you will inevitably be disappointed, just as explanations of stage illusions exterminate the spell of magic that we experience as we watch the impossible occur. Impossible crimes cannot be impossible, as the detective will quickly point out, because they have happened. Treasure has been stolen from a locked and guarded room or museum or library, in spite of the constant surveillance by trained policemen. A frightened victim-to-be has locked, bolted, and sealed his home because the murderer has warned him that he will die at midnight, and a brigade of officers in a cordon surrounding the house cannot prevent it.

If the mind of a diabolical genius can invent a method of robbery or murder that appears to be insoluble, then surely there must be a mind of equal brilliance that is able to penetrate the scheme and explain its every nuance. That is the detective’s role and, although he appears to be explaining it all to the police and other interested parties, he is, of course, describing the scenario to the reader. The curtain that has masked the magic, that has screened the illusion, is raised, and all returns to ordinary mechanics, physics, and psychology—the stuff of everyday life.

Therefore, if you want to maintain the beauty of a magic show, refuse to listen to a magician who is willing to explain how he performed his illusion. Similarly, if the situations in these locked-room mysteries have provided a delicious frisson of wonder, stop reading them as soon as you reach the denouement.

No, of course you can’t do that. It is human nature to want to know, and the moment of clarity, when all is revealed, brings a different kind of satisfaction. Admiration replaces awe. The legerdemain achieved by the authors of the stories in this volume is, to use a word that has sadly become cheapened by overuse, awesome.

While it is true that Poe invented the locked-room story (although Robert Adey, in the introduction to his monumental bibliography, Locked Room Murders, gives credit to a pioneering effort by the great Irish novelist Sheridan Le Fanu, claiming the honor of first story for “A Passage in the Secret History of an Irish Countess,” which appeared in the November 1838 issue of Dublin University Magazine and was later reprinted in the posthumously published The Purcell Papers in 1880), there can be no argument that the greatest practitioner of this demanding form was John Dickson Carr.

Not only did Carr produce one hundred twenty-six novels, short stories, and radio plays under his own name and as Carter Dickson, but the range of seemingly impossible murder methods he created was so broad and varied that it simply freezes the brain to contemplate. In perhaps the most arrogant display of his command of the locked-room mystery, in his 1935 novel The Three Coffins (published in England as The Hollow Man), he has his series detective, Dr. Gideon Fell, deliver a lecture to a captivated audience. In this display of erudition, Fell spends fifteen pages enumerating all the ways in which a locked room does not turn out to be impenetrable after all, and in which the impossible is clearly explained. He offers scores of ideas for solutions to the most challenging puzzles in the mystery genre, tossing off in rapid succession a greater cornucopia of invention than most mystery writers will conceive in a lifetime. When he has concluded his seemingly comprehensive tutorial, he informs the attendees that none of these explanations are pertinent to the present case and heads off to conclude the investigation.

Many solutions to the feats of prestidigitation in this collection will have been covered in Fell’s lecture, but the sheer inventive genius of many of the contributors will have exceeded even Carr’s tour de force. In his brilliant history of the mystery genre, Murder for Pleasure (1941), Howard Haycraft warned writers of detective fiction to stay away from the locked-room puzzle because “only a genius can invest it with novelty or interest today.” It should be pointed out that, however well-intentioned the admonition, nearly half the stories in this volume were written after the publication date of that cornerstone history and appreciation of the literature of crime.

The locked-room mystery reached its pinnacle of popularity during the Golden Age of detective fiction between the two world wars. This is when Agatha Christie flourished, and so did Dorothy L. Sayers, Ellery Queen, Clayton Rawson, R. Austin Freeman, Margery Allingham, and, of course, Carr. In those years, the emphasis, particularly in England, was on the creation and solution of a puzzle. Readers were more interested in who dunnit, and how dunnit, whereas in the more modern era a greater focus has been placed on why dunnit. Murder—the taking of another person’s life—was a private affair and its solution demanded a ritual that was largely followed by most writers. The book or short story generally began with a fairly tranquil community (even if that community was in a big city such as London or New York) in which all the participants knew each other. A terrible crime, usually murder, occurred, rending the social fabric. The police came to investigate, usually a single detective rather than an entire team of forensic experts, and either he (there were precious few female police officers in the detective stories of that era) would solve the mystery or show himself to be an abject fool, relying on a gifted, and frequently eccentric, amateur to arrive at a conclusion. Clues were placed judiciously throughout the story as the author challenged the reader to solve the case before the protagonist did. The true colors of the least likely suspect were then revealed and he or she was taken into custody, returning the community to its formerly peaceful state.

Many current readers don’t have the patience to follow the trail of clues in a detective story in which all suspects are interviewed (interrogated is a word for later mysteries), all having doubt cast on their alibis, their relationships with the victim, and their possible motives, until all the suspects are gathered for the explanation of how the crime was committed, who perpetrated it, and why they did it. It is not realistic and was never intended to be. It is entertainment, as all fiction is . . . or should be. Dorothy L. Sayers pointed out that people have amused themselves by creating riddles, conundrums, and puzzles of all kinds, apparently the sole purpose of which is the satisfaction they give themselves by deducing a solution. Struggling with a Rubik’s Cube is a form of torment eliciting a tremendous sense of achievement and joy when it is solved. This is equally true of reading a good detective story, the apotheosis of which is the locked-room puzzle, with the added pleasure of becoming involved with fascinating, occasionally memorable characters, unusual backgrounds, and, when the sun is shining most brightly, told with captivating prose.

Don’t read these stories on a subway train or in the backseat of a car. They want to be read when you are comfortably ensconced in an easy chair or a bed piled high with pillows, at your leisure, perhaps with a cup of tea or a glass of port. Oh, heaven!

THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE

EDGAR ALLAN POE

“THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE” is, without question, the single most important story in the history of mystery fiction. In these few pages, Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849) invented most of the significant elements in a literary form that relied on this template for the next one hundred seventy years: the brilliant detective, his somewhat dimmer sidekick, the still dimmer official police, the apparently impossible crime, misleading clues, the observation of disparate bits of information and the inspired deduction that results, and the denouement in which all is made clear.

Born in Boston and orphaned at the age of two when both his parents died of tuberculosis, Poe was taken in by a wealthy merchant, John Allan, and his wife; although never legally adopted, Poe nonetheless took Allan for his name. He received a classical education in Scotland and England from 1815 to 1820. After returning to the United States, he published his first book, Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827). It, and his next two volumes of poetry, were financial disasters. He won a prize for his story “MS. Found in a Bottle” (1833) and began a series of jobs as editor and critic of several periodicals. While he dramatically increased their circulations, his alcoholism, strong views, and arrogance enraged his bosses, costing him one job after another. He married his thirteen-year-old cousin, Virginia, living in abject poverty for many years with her and her mother. Lack of money undoubtedly contributed to the death of his wife at twenty-four. The most brilliant literary critic of his time, the master of horror stories, the poet whose work remains familiar and beloved to the present day, and the inventor of the detective story, Poe died a pauper.

“The Murders in the Rue Morgue” was first published in the April 1841 issue of Graham’s Magazine. It was first published in book form (if a forty-eight-page pamphlet may be counted as a book) in a very rare volume (a copy in collectors’ condition would sell for at least two hundred fifty thousand dollars) titled Prose Romances (Philadelphia, Graham, 1843), which also contains “The Man That Was Used Up.” It then was collected in Tales (New York, Wiley & Putnam, 1845).

THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE

EDGAR ALLAN POE

What song the Syrens sang, or what name Achilles assumed when he hid himself among women, although puzzling questions, are not beyond all conjecture.

—Sir Thomas Browne

THE MENTAL FEATURES discoursed of as the analytical, are, in themselves, but little susceptible of analysis. We appreciate them only in their effects. We know of them, among other things, that they are always to their possessor, when inordinately possessed, a source of the liveliest enjoyment. As the strong man exults in his physical ability, delighting in such exercises as call his muscles into action, so glories the analyst in that moral activity which disentangles. He derives pleasure from even the most trivial occupations bringing his talent into play. He is fond of enigmas, of conundrums, hieroglyphics; exhibiting in his solutions of each a degree of acumen which appears to the ordinary apprehension præternatural. His results, brought about by the very soul and essence of method, have, in truth, the whole air of intuition.

The faculty of re-solution is possibly much invigorated by mathematical study, and especially by that highest branch of it which, unjustly, and merely on account of its retrograde operations, has been called, as if par excellence, analysis. Yet to calculate is not in itself to analyze. A chess-player, for example, does the one, without effort at the other. It follows that the game of chess, in its effect upon mental character, is greatly misunderstood. I am not now writing a treatise, but simply prefacing a somewhat peculiar narrative by observations very much at random; I will, therefore, take occasion to assert that the higher powers of the reflective intellect are more decidedly and more usefully tasked by the unostentatious game of draughts than by all the elaborate frivolity of chess. In this latter, where the pieces have different and bizarre motions, with various and variable values, what is only complex, is mistaken (a not unusual error) for what is profound. The attention is here called powerfully into play. If it flag for an instant, an oversight is committed, resulting in injury or defeat. The possible moves being not only manifold, but involute, the chances of such oversights are multiplied; and in nine cases out of ten, it is the more concentrative rather than the more acute player who conquers. In draughts, on the contrary, where the moves are unique and have but little variation, the probabilities of inadvertence are diminished, and the mere attention being left comparatively unemployed, what advantages are obtained by either party are obtained by superior acumen. To be less abstract, let us suppose a game of draughts where the pieces are reduced to four kings, and where, of course, no oversight is to be expected. It is obvious that here the victory can be decided (the players being at all equal) only by some récherché movement, the result of some strong exertion of the intellect. Deprived of ordinary resources, the analyst throws himself into the spirit of his opponent, identifies himself therewith, and not unfrequently sees thus, at a glance, the sole methods (sometimes indeed absurdly simple ones) by which he may seduce into error or hurry into miscalculation.

Whist has long been known for its influence upon what is termed the calculating power; and men of the highest order of intellect have been known to take an apparently unaccountable delight in it, while eschewing chess as frivolous. Beyond doubt there is nothing of a similar nature so greatly tasking the faculty of analysis. The best chess-player in Christendom may be little more than the best player of chess; but proficiency in whist implies capacity for success in all these more important undertakings where mind struggles with mind. When I say proficiency, I mean that perfection in the game which includes a comprehension of all the sources whence legitimate advantage may be derived. These are not only manifold, but multiform, and lie frequently among recesses of thought altogether inaccessible to the ordinary understanding. To observe attentively is to remember distinctly; and, so far, the concentrative chess-player will do very well at whist; while the rules of Hoyle (themselves based upon the mere mechanism of the game) are sufficiently and generally comprehensible. Thus to have a retentive memory, and proceed by “the book” are points commonly regarded as the sum total of good playing. But it is in matters beyond the limits of mere rule that the skill of the analyst is evinced. He makes, in silence, a host of observations and inferences. So, perhaps, do his companions; and the difference in the extent of the information obtained, lies not so much in the validity of the inference as in the quality of the observation. The necessary knowledge is that of what to observe. Our player confines himself not at all; nor, because the game is the object, does he reject deductions from things external to the game. He examines the countenance of his partner, comparing it carefully with that of each of his opponents. He considers the mode of assorting the cards in each hand; often counting trump by trump, and honor by honor, through the glances bestowed by their holders upon each. He notes every variation of face as the play progresses, gathering a fund of thought from the differences in the expression of certainty, of surprise, of triumph, or chagrin. From the manner of gathering up a trick he judges whether the person taking it can make another in the suit. He recognizes what is played through feint, by the manner with which it is thrown upon the table. A casual or inadvertent word; the accidental dropping or turning of a card, with the accompanying anxiety or carelessness in regard to its concealment; the counting of the tricks, with the order of their arrangement; embarrassment, hesitation, eagerness, or trepidation—all afford, to his apparently intuitive perception, indications of the true state of affairs. The first two or three rounds having been played, he is in full possession of the contents of each hand, and thenceforward puts down his cards with as absolute a precision of purpose as if the rest of the party had turned outward the faces of their own.

The analytical power should not be confounded with simple ingenuity; for while the analyst is necessarily ingenious, the ingenious man is often remarkably incapable of analysis. The constructive or combining power, by which ingenuity is usually manifested, and to which the phrenologists (I believe erroneously) have assigned a separate organ, supposing it a primitive faculty, has been so frequently seen in those whose intellect bordered otherwise upon idiocy, as to have attracted general observation among writers on morals. Between ingenuity and the analytic ability there exists a difference far greater, indeed, than that between the fancy and the imagination, but of a character very strictly analogous. It will be found, in fact, that the ingenious are always fanciful, and the truly imaginative never otherwise than analytic.

The narrative which follows will appear to the reader somewhat in the light of a commentary upon the propositions just advanced.

Residing in Paris during the spring and part of the summer of 18——, I there became acquainted with a Monsieur C. Auguste Dupin. This young gentleman was of an excellent, indeed of an illustrious family, but, by a variety of untoward events, had been reduced to such poverty that the energy of his character succumbed beneath it, and he ceased to bestir himself in the world, or to care for the retrieval of his fortunes. By courtesy of his creditors, there still remained in his possession a small remnant of his patrimony; and, upon the income arising from this, he managed, by means of a rigorous economy, to procure the necessities of life, without troubling himself about its superfluities. Books, indeed, were his sole luxuries, and in Paris these are easily obtained.

Our first meeting was at an obscure library in the Rue Montmartre, where the accident of our both being in search of the same very rare and very remarkable volume brought us into closer communion. We saw each other again and again. I was deeply interested in the little family history which he detailed to me with all that candor which a Frenchman indulges whenever mere self is the theme. I was astonished, too, at the vast extent of his reading; and, above all, I felt my soul enkindled within me by the wild fervor, and the vivid freshness of his imagination. Seeking in Paris the objects I then sought, I felt that the society of such a man would be to me a treasure beyond price; and this feeling I frankly confided to him. It was at length arranged that we should live together during my stay in the city; and as my worldly circumstances were somewhat less embarrassed than his own, I was permitted to be at the expense of renting, and furnishing in a style which suited the rather fantastic gloom of our common temper, a time-eaten and grotesque mansion, long deserted through superstitions into which we did not inquire, and tottering to its fall in a retired and desolate portion of the Faubourg St. Germain.

Had the routine of our life at this place been known to the world, we should have been regarded as madmen—although, perhaps, as madmen of a harmless nature. Our seclusion was perfect. We admitted no visitors. Indeed the locality of our retirement had been carefully kept a secret from my own former associates; and it had been many years since Dupin had ceased to know or be known in Paris. We existed within ourselves alone.

It was a freak of fancy in my friend (for what else shall I call it?) to be enamored of the night for her own sake; and into this bizarrerie, as into all his others, I quietly fell; giving myself up to his wild whims with a perfect abandon. The sable divinity would not herself dwell with us always; but we could counterfeit her presence. At the first dawn of the morning we closed all the massy shutters of our old building; lighted a couple of tapers which, strongly perfumed, threw out only the ghastliest and feeblest of rays. By the aid of these we then busied our souls in dreams—reading, writing, or conversing, until warned by the clock of the advent of the true Darkness. Then we sallied forth into the streets, arm in arm, continuing the topics of the day, or roaming far and wide until a late hour, seeking, amid the wild lights and shadows of the populous city, that infinity of mental excitement which quiet observation can afford.

At such times I could not help remarking and admiring (although from his rich ideality I had been prepared to expect it) a peculiar analytic ability in Dupin. He seemed, too, to take an eager delight in its exercise—if not exactly in its display—and did not hesitate to confess the pleasure thus derived. He boasted to me, with a low chuckling laugh, that most men, in respect to himself, wore windows in their bosoms, and was wont to follow up such assertions by direct and very startling proofs of his intimate knowledge of my own. His manner at these moments was frigid and abstract; his eyes were vacant in expression; while his voice, usually a rich tenor, rose into a treble which would have sounded petulant but for the deliberateness and entire distinctness of the enunciation. Observing him in these moods, I often dwelt meditatively upon the old philosophy of the Bi-Part Soul, and amused myself with the fancy of a double Dupin—the creative and the resolvent.

Let it not be supposed, from what I have just said, that I am detailing any mystery, or penning any romance. What I have described in the Frenchman was merely the result of an excited, or perhaps of a diseased, intelligence. But of the character of his remarks at the periods in question an example will best convey the idea.

We were strolling one night down a long dirty street, in the vicinity of the Palais Royal. Being both, apparently, occupied with thought, neither of us had spoken a syllable for fifteen minutes at least. All at once Dupin broke forth with these words:

“He is a very little fellow, that’s true, and would do better for the Théâtre des Variétés.”

“There can be no doubt of that,” I replied, unwittingly, and not at first observing (so much had I been absorbed in reflection) the extraordinary manner in which the speaker had chimed in with my meditations. In an instant afterward I recollected myself, and my astonishment was profound.

“Dupin,” said I, gravely, “this is beyond my comprehension. I do not hesitate to say that I am amazed, and can scarcely credit my senses. How was it possible you should know I was thinking of——?” Here I paused, to ascertain beyond a doubt whether he really knew of whom I thought.

“——of Chantilly,” said he, “why do you pause? You were remarking to yourself that his diminutive figure unfitted him for tragedy.”

This was precisely what had formed the subject of my reflections. Chantilly was a quondam cobbler of the Rue St. Denis, who, becoming stage-mad, had attempted the rôle of Xerxes, in Crébillon’s tragedy so called, and been notoriously Pasquinaded for his pains.

“Tell me, for Heaven’s sake,” I exclaimed, “the method—if method there is—by which you have been enabled to fathom my soul in this matter.” In fact, I was even more startled than I would have been willing to express.

“It was the fruiterer,” replied my friend, “who brought you to the conclusion that the mender of soles was not of sufficient height for Xerxes et id genus omne.”

“The fruiterer!—you astonish me—I know no fruiterer whomsoever.”

“The man who ran up against you as we entered the street—it may have been fifteen minutes ago.”

I now remembered that, in fact, a fruiterer, carrying upon his head a large basket of apples, had nearly thrown me down, by accident, as we passed from the Rue C——into the thoroughfare where we stood; but what this had to do with Chantilly I could not possibly understand.

There was not a particle of charlatanerie about Dupin. “I will explain,” he said, “and that you may comprehend all clearly, we will first retrace the course of your meditations, from the moment in which I spoke to you until that of the rencontre with the fruiterer in question. The larger links of the chain run thus—Chantilly, Orion, Dr. Nichols, Epicurus, Stereotomy, the street stones, the fruiterer.”

There are few persons who have not, at some period of their lives, amused themselves in retracing the steps by which particular conclusions of their own minds have been attained. The occupation is often full of interest; and he who attempts it for the first time is astonished by the apparently illimitable distance and incoherence between the starting-point and the goal. What, then, must have been my amazement, when I heard the Frenchman speak what he had just spoken, and when I could not help acknowledging that he had spoken the truth. He continued:

“We had been talking of horses, if I remember aright, just before leaving the Rue C——. This was the last subject we discussed. As we crossed into this street, a fruiterer, with a large basket upon his head, brushing quickly past us, thrust you upon a pile of paving-stones collected at a spot where the causeway is undergoing repair. You stepped upon one of the loose fragments, slipped, slightly strained your ankle, appeared vexed or sulky, muttered a few words, turned to look at the pile, and then proceeded in silence. I was not particularly attentive to what you did; but observation has become with me, of late, a species of necessity.

“You kept your eyes upon the ground—glancing, with a petulant expression, at the holes and ruts in the pavement (so that I saw you were still thinking of the stones), until we reached the little alley called Lamartine, which has been paved, by way of experiment, with the overlapping and riveted blocks. Here your countenance brightened up, and, perceiving your lips move, I could not doubt that you murmured the word ‘stereotomy,’ a term very affectedly applied to this species of pavement. I knew that you could not say to yourself ‘stereotomy’ without being brought to think of atomies, and thus of the theories of Epicurus; and since, when we discussed this subject not very long ago, I mentioned to you how singularly, yet with how little notice, the vague guesses of that noble Greek had met with confirmation in the late nebular cosmogony, I felt that you could not avoid casting your eyes upward to the great nebula in Orion, and I certainly expected that you would do so. You did look up; and I was now assured that I had correctly followed your steps. But in that bitter tirade upon Chantilly, which appeared in yesterday’s ‘Musée,’ the satirist, making some disgraceful allusions to the cobbler’s change of name upon assuming the buskin, quoted a Latin line about which we have often conversed. I mean the line

Perdidit antiquum litera prima sonum.

I had told you that this was in reference to Orion, formerly written Urion; and, from certain pungencies connected with this explanation, I was aware that you could not have forgotten it. It was clear, therefore, that you would not fail to combine the two ideas of Orion and Chantilly. That you did combine them I saw by the character of the smile which passed over your lips. You thought of the poor cobbler’s immolation. So far, you had been stooping in your gait; but now I saw you draw yourself up to your full height. I was then sure that you reflected upon the diminutive figure of Chantilly. At this point I interrupted your meditations to remark that as, in fact, he was a very little fellow—that Chantilly—he would do better at the Théâtre des Variétés.”

Not long after this, we were looking over an evening edition of the Gazette des Tribunaux, when the following paragraphs arrested our attention.

“EXTRAORDINARY MURDERS.—This morning, about three o’clock, the inhabitants of the Quartier St. Roch were roused from sleep by a succession of terrific shrieks, issuing, apparently, from the fourth story of a house in the Rue Morgue, known to be in the sole occupancy of one Madame L’Espanaye, and her daughter, Mademoiselle Camille L’Espanaye. After some delay, occasioned by a fruitless attempt to procure admission in the usual manner, the gateway was broken in with a crowbar, and eight or ten of the neighbors entered, accompanied by two gendarmes. By this time the cries had ceased; but, as the party rushed up the first flight of stairs, two or more rough voices, in angry contention, were distinguished, and seemed to proceed from the upper part of the house. As the second landing was reached, these sounds, also, had ceased, and every thing remained perfectly quiet. The party spread themselves, and hurried from room to room. Upon arriving at a large back chamber in the fourth story (the door of which, being found locked, with the key inside, was forced open), a spectacle presented itself which struck every one present not less with horror than with astonishment.

“The apartment was in the wildest disorder—the furniture broken and thrown about in all directions. There was only one bedstead; and from this the bed had been removed, and thrown into the middle of the floor. On a chair lay a razor, besmeared with blood. On the hearth were two or three long and thick tresses of gray human hair, also dabbled with blood, and seeming to have been pulled out by the roots. Upon the floor were found four Napoleons, an ear-ring of topaz, three large silver spoons, three smaller of métal d’Alger, and two bags, containing nearly four thousand francs in gold. The drawers of a bureau, which stood in one corner, were open, and had been, apparently, rifled, although many articles still remained in them. A small iron safe was discovered under the bed (not under the bedstead). It was open, with the key still in the door. It had no contents beyond a few old letters, and other papers of little consequence.

“Of Madame L’Espanaye no traces were here seen; but an unusual quantity of soot being observed in the fire-place, a search was made in the chimney, and (horrible to relate!) the corpse of the daughter, head downward, was dragged therefrom; it having been thus forced up the narrow aperture for a considerable distance. The body was quite warm. Upon examining it, many excoriations were perceived, no doubt occasioned by the violence with which it had been thrust up and disengaged. Upon the face were many severe scratches, and, upon the throat, dark bruises, and deep indentations of finger nails, as if the deceased had been throttled to death.

“After a thorough investigation of every portion of the house without farther discovery, the party made its way into a small paved yard in the rear of the building, where lay the corpse of the old lady, with her throat so entirely cut that, upon an attempt to raise her, the head fell off. The body, as well as the head, was fearfully mutilated—the former so much so as scarcely to retain any semblance of humanity.

“To this horrible mystery there is not as yet, we believe, the slightest clew.”

The next day’s paper had these additional particulars:

“The Tragedy in the Rue Morgue.—Many individuals have been examined in relation to this most extraordinary and frightful affair,” [the word ‘affaire’ has not yet, in France, that levity of import which it conveys with us] “but nothing whatever has transpired to throw light upon it. We give below all the material testimony elicited.

“Pauline Dubourg, laundress, deposes that she has known both the deceased for three years, having washed for them during that period. The old lady and her daughter seemed on good terms—very affectionate toward each other. They were excellent pay. Could not speak in regard to their mode or means of living. Believe that Madame L. told fortunes for a living. Was reputed to have money put by. Never met any person in the house when she called for the clothes or took them home. Was sure that they had no servant in employ. There appeared to be no furniture in any part of the building except in the fourth story.

“Pierre Moreau, tobacconist, deposes that he has been in the habit of selling small quantities of tobacco and snuff to Madame L’Espanaye for nearly four years. Was born in the neighborhood, and has always resided there. The deceased and her daughter had occupied the house in which the corpses were found for more than six years. It was formerly occupied by a jeweller, who under-let the upper rooms to various persons. The house was the property of Madame L. She became dissatisfied with the abuse of the premises by her tenant, and moved into them herself, refusing to let any portion. The old lady was childish. Witness had seen the daughter some five or six times during the six years. The two lived an exceedingly retired life—were reputed to have money. Had heard it said among the neighbors that Madame L. told fortunes—did not believe it. Had never seen any person enter the door except the old lady and her daughter, a porter once or twice, and a physician some eight or ten times.

“Many other persons, neighbors, gave evidence to the same effect. No one was spoken of as frequenting the house. It was not known whether there were any living connections of Madame L. and her daughter. The shutters of the front windows were seldom opened. Those in the rear were always closed, with the exception of the large back room, fourth story. The house was a good house—not very old.

“Isidore Musèt, gendarme, deposes that he was called to the house about three o’clock in the morning, and found some twenty or thirty persons at the gateway, endeavoring to gain admittance. Forced it open, at length, with a bayonet—not with a crowbar. Had but little difficulty in getting it open, on account of its being a double or folding gate, and bolted neither at bottom nor top. The shrieks were continued until the gate was forced—and then suddenly ceased. They seemed to be screams of some person (or persons) in great agony—were loud and drawn out, not short and quick. Witness led the way up stairs. Upon reaching the first landing, heard two voices in loud and angry contention—the one a gruff voice, the other much shriller—a very strange voice. Could distinguish some words of the former, which was that of a Frenchman. Was positive that it was not a woman’s voice. Could distinguish the words ‘sacré’ and ‘diable.’ The shrill voice was that of a foreigner. Could not be sure whether it was the voice of a man or of a woman. Could not make out what was said, but believed the language to be Spanish. The state of the room and of the bodies was described by this witness as we described them yesterday.

“Henri Duval, a neighbor, and by trade a silver-smith, deposes that he was one of the party who first entered the house. Corroborates the testimony of Musèt in general. As soon as they forced an entrance, they reclosed the door, to keep out the crowd, which collected very fast, notwithstanding the lateness of the hour. The shrill voice, this witness thinks, was that of an Italian. Was certain it was not French. Could not be sure that it was a man’s voice. It might have been a woman’s. Was not acquainted with the Italian language. Could not distinguish the words, but was convinced by the intonations that the speaker was an Italian. Knew Madame L. and her daughter. Had conversed with both frequently. Was sure that the shrill voice was not that of either of the deceased.

“——Odenheimer, restaurateur.—This witness volunteered his testimony. Not speaking French, was examined through an interpreter. Is a native of Amsterdam. Was passing the house at the time of the shrieks. They lasted for several minutes—probably ten. They were long and loud—very awful and distressing. Was one of those who entered the building. Corroborated the previous evidence in every respect but one. Was sure that the shrill voice was that of a man—of a Frenchman. Could not distinguish the words uttered. They were loud and quick—unequal—spoken apparently in fear as well as in anger. The voice was harsh—not so much shrill as harsh. Could not call it a shrill voice. The gruff voice said repeatedly, ‘sacré,’ ‘diable,’ and once ‘mon Dieu.’

“Jules Mignaud, banker, of the firm of Mignaud et Fils, Rue Deloraine. Is the elder Mignaud. Madame L’Espanaye had some property. Had opened an account with his banking house in the spring of the year——(eight years previously). Made frequent deposits in small sums. Had checked for nothing until the third day before her death, when she took out in person the sum of 4000 francs. This sum was paid in gold, and a clerk sent home with the money.

“Adolphe Le Bon, clerk to Mignaud et Fils, deposes that on the day in question, about noon, he accompanied Madame L’Espanaye to her residence with the 4000 francs, put up in two bags. Upon the door being opened, Mademoiselle L. appeared and took from his hands one of the bags, while the old lady relieved him of the other. He then bowed and departed. Did not see any person in the street at the time. It is a bystreet—very lonely.

“William Bird, tailor, deposes that he was one of the party who entered the house. Is an Englishman. Has lived in Paris two years. Was one of the first to ascend the stairs. Heard the voices in contention. The gruff voice was that of a Frenchman. Could make out several words, but cannot now remember all. Heard distinctly ‘sacré’ and ‘mon Dieu.’ There was a sound at the moment as if of several persons struggling—a scraping and scuffling sound. The shrill voice was very loud—louder than the gruff one. Is sure that it was not the voice of an Englishman. Appeared to be that of a German. Might have been a woman’s voice. Does not understand German.

“Four of the above-named witnesses, being recalled, deposed that the door of the chamber in which was found the body of Mademoiselle L. was locked on the inside when the party reached it. Every thing was perfectly silent—no groans or noises of any kind. Upon forcing the door no person was seen. The windows, both of the back and front room, were down and firmly fastened from within. A door between the two rooms was closed but not locked. The door leading from the front room into the passage was locked, with the key on the inside. A small room in the front of the house, on the fourth story, at the head of the passage, was open, the door being ajar. This room was crowded with old beds, boxes, and so forth. These were carefully removed and searched. There was not an inch of any portion of the house which was not carefully searched. Sweeps were sent up and down the chimneys. The house was a four-story one, with garrets (mansardes). A trap-door on the roof was nailed down very securely—did not appear to have been opened for years. The time elapsing between the hearing of the voices in contention and the breaking open of the room door was variously stated by the witnesses. Some made it as short as three minutes—some as long as five. The door was opened with difficulty.

“Alfonzo Garcio, undertaker, deposes that he resides in the Rue Morgue. Is a native of Spain. Was one of the party who entered the house. Did not proceed up stairs. Is nervous, and was apprehensive of the consequences of agitation. Heard the voices in contention. The gruff voice was that of a Frenchman. Could not distinguish what was said. The shrill voice was that of an Englishman—is sure of this. Does not understand the English language, but judges by the intonation.

“Alberto Montani, confectioner, deposes that he was among the first to ascend the stairs. Heard the voices in question. The gruff voice was that of a Frenchman. Distinguished several words. The speaker appeared to be expostulating. Could not make out the words of the shrill voice. Spoke quick and unevenly. Thinks it the voice of a Russian. Corroborates the general testimony. Is an Italian. Never conversed with a native of Russia.

“Several witnesses, recalled, here testified that the chimneys of all the rooms on the fourth story were too narrow to admit the passage of a human being. By ‘sweeps’ were meant cylindrical sweeping-brushes, such as are employed by those who clean chimneys. These brushes were passed up and down every flue in the house. There is no back passage by which any one could have descended while the party proceeded up stairs. The body of Mademoiselle L’Espanaye was so firmly wedged in the chimney that it could not be got down until four or five of the party united their strength.

“Paul Dumas, physician, deposes that he was called to view the bodies about daybreak. They were both then lying on the sacking of the bedstead in the chamber where Mademoiselle L. was found. The corpse of the young lady was much bruised and excoriated. The fact that it had been thrust up the chimney would sufficiently account for these appearances. The throat was greatly chafed. There were several deep scratches just below the chin, together with a series of livid spots which were evidently the impression of fingers. The face was fearfully discolored, and the eyeballs protruded. The tongue had been partially bitten through. A large bruise was discovered upon the pit of the stomach, produced, apparently, by the pressure of a knee. In the opinion of M. Dumas, Mademoiselle L’Espanaye had been throttled to death by some person or persons unknown. The corpse of the mother was horribly mutilated. All the bones of the right leg and arm were more or less shattered. The left tibia much splintered, as well as all the ribs of the left side. Whole body dreadfully bruised and discolored. It was not possible to say how the injuries had been inflicted. A heavy club of wood, or a broad bar of iron—a chair—any large, heavy, and obtuse weapon would have produced such results, if wielded by the hands of a very powerful man. No woman could have inflicted the blows with any weapon. The head of the deceased, when seen by witness, was entirely separated from the body, and was also greatly shattered. The throat had evidently been cut with some very sharp instrument—probably with a razor.

“Alexandre Etienne, surgeon, was called with M. Dumas to view the bodies. Corroborated the testimony, and the opinions of M. Dumas.

“Nothing further of importance was elicited, although several other persons were examined. A murder so mysterious, and so perplexing in all its particulars, was never before committed in Paris—if indeed a murder has been committed at all. The police are entirely at fault—an unusual occurrence in affairs of this nature. There is not, however, the shadow of a clew apparent.”

The evening edition of the paper stated that the greatest excitement still continued in the Quartier St. Roch—that the premises in question had been carefully researched, and fresh examinations of witnesses instituted, but all to no purpose. A postscript, however, mentioned that Adolphe Le Bon had been arrested and imprisoned—although nothing appeared to criminate him beyond the facts already detailed.

Dupin seemed singularly interested in the progress of this affair—at least so I judged from his manner, for he made no comments. It was only after the announcement that Le Bon had been imprisoned that he asked me my opinion respecting the murders.

I could merely agree with all Paris in considering them an insoluble mystery. I saw no means by which it would be possible to trace the murderer.

“We must not judge of the means,” said Dupin, “by this shell of an examination. The Parisian police, so much extolled for acumen, are cunning, but no more. There is no method in their proceedings, beyond the method of the moment. They make a vast parade of measures; but, not unfrequently, these are so ill-adapted to the objects proposed, as to put us in mind of Monsieur Jourdain’s calling for his robe-de-chambre—pour mieux entendre la musique. The results attained by them are not unfrequently surprising, but, for the most part, are brought about by simple diligence and activity. When these qualities are unavailing, their schemes fail. Vidocq, for example, was a good guesser, and a persevering man. But, without educated thought, he erred continually by the very intensity of his investigations. He impaired his vision by holding the object too close. He might see, perhaps, one or two points with unusual clearness, but in so doing he, necessarily, lost sight of the matter as a whole. Thus there is such a thing as being too profound. Truth is not always in a well. In fact, as regards the more important knowledge, I do believe that she is invariably superficial. The depth lies in the valleys where we seek her, and not upon the mountain-tops where she is found. The modes and sources of this kind of error are well typified in the contemplation of the heavenly bodies. To look at a star by glances—to view it in a sidelong way, by turning toward it the exterior portions of the retina (more susceptible of feeble impressions of light than the interior), is to behold the star distinctly—is to have the best appreciation of its lustre—a lustre which grows dim just in proportion as we turn our vision fully upon it. A greater number of rays actually fall upon the eye in the latter case, but in the former, there is the more refined capacity for comprehension. By undue profundity we perplex and enfeeble thought; and it is possible to make even Venus herself vanish from the firmament by a scrutiny too sustained, too concentrated, or too direct.

“As for these murders, let us enter into some examinations for ourselves, before we make up an opinion respecting them. An inquiry will afford us amusement,” [I thought this an odd term, so applied, but said nothing] “and besides, Le Bon once rendered me a service for which I am not ungrateful. We will go and see the premises with our own eyes. I know G——, the Prefect of Police, and shall have no difficulty in obtaining the necessary permission.”

The permission was obtained, and we proceeded at once to the Rue Morgue. This is one of those miserable thoroughfares which intervene between the Rue Richelieu and the Rue St. Roch. It was late in the afternoon when we reached it, as this quarter is at a great distance from that in which we resided. The house was readily found; for there were still many persons gazing up at the closed shutters, with an objectless curiosity, from the opposite side of the way. It was an ordinary Parisian house, with a gateway, on one side of which was a glazed watch-box, with a sliding panel in the window, indicating a loge de concierge. Before going in we walked up the street, turned down an alley, and then, again turning, passed in the rear of the building—Dupin, meanwhile, examining the whole neighborhood, as well as the house, with a minuteness of attention for which I could see no possible object.

Retracing our steps we came again to the front of the dwelling, rang, and, having shown our credentials, were admitted by the agents in charge. We went up stairs—into the chamber where the body of Mademoiselle L’Espanaye had been found, and where both the deceased still lay. The disorders of the room had, as usual, been suffered to exist. I saw nothing beyond what had been stated in the Gazette des Tribunaux. Dupin scrutinized every thing—not excepting the bodies of the victims. We then went into the other rooms, and into the yard; a gendarme accompanying us throughout. The examination occupied us until dark, when we took our departure. On our way home my companion stepped in for a moment at the office of one of the daily papers.

I have said that the whims of my friend were manifold, and that Je les ménagais:—for this phrase there is no English equivalent. It was his humor, now, to decline all conversation on the subject of the murder, until about noon the next day. He then asked me, suddenly, if I had observed any thing peculiar at the scene of the atrocity.

There was something in his manner of emphasizing the word “peculiar,” which caused me to shudder, without knowing why.

“No, nothing peculiar,” I said; “nothing more, at least, than we both saw stated in the paper.”

“The Gazette,” he replied, “has not entered, I fear, into the unusual horror of the thing. But dismiss the idle opinions of this print. It appears to me that this mystery is considered insoluble, for the very reason which should cause it to be regarded as easy of solution—I mean for the outré character of its features. The police are confounded by the seeming absence of motive—not for the murder itself—but for the atrocity of the murder. They are puzzled, too, by the seeming impossibility of reconciling the voices heard in contention with the facts that no one was discovered upstairs but the assassinated Mademoiselle L’Espanaye, and that there were no means of egress without the notice of the party ascending. The wild disorder of the room; the corpse thrust, with the head downward, up the chimney; the frightful mutilation of the body of the old lady; these considerations, with those just mentioned, and others which I need not mention, have sufficed to paralyze the powers, by putting completely at fault the boasted acumen, of the government agents. They have fallen into the gross but common error of confounding the unusual with the abstruse. But it is by these deviations from the plane of the ordinary, that reason feels its way, if at all, in its search for the true. In investigations such as we are now pursuing, it should not be so much asked ‘what has occurred,’ as ‘what has occurred that has never occurred before.’ In fact, the facility with which I shall arrive, or have arrived, at the solution of this mystery, is in the direct ratio of its apparent insolubility in the eyes of the police.”

I stared at the speaker in mute astonishment.

“I am now awaiting,” continued he, looking toward the door of our apartment—“I am now awaiting a person who, although perhaps not the perpetrator of these butcheries, must have been in some measure implicated in their perpetration. Of the worst portion of the crimes committed, it is probable that he is innocent. I hope that I am right in this supposition; for upon it I build my expectation of reading the entire riddle. I look for the man here—in this room—every moment. It is true that he may not arrive; but the probability is that he will. Should he come, it will be necessary to detain him. Here are pistols; and we both know how to use them when occasion demands their use.”

I took the pistols, scarcely knowing what I did, or believing what I heard, while Dupin went on, very much as if in a soliloquy. I have already spoken of his abstract manner at such times. His discourse was addressed to myself; but his voice, although by no means loud, had that intonation which is commonly employed in speaking to some one at a great distance. His eyes, vacant in expression, regarded only the wall.

“That the voices heard in contention,” he said, “by the party upon the stairs, were not the voices of the women themselves, was fully proved by the evidence. This relieves us of all doubt upon the question whether the old lady could have first destroyed the daughter, and afterward have committed suicide. I speak of this point chiefly for the sake of method; for the strength of Madame L’Espanaye would have been utterly unequal to the task of thrusting her daughter’s corpse up the chimney as it was found; and the nature of the wounds upon her own person entirely precludes the idea of self-destruction. Murder, then, has been committed by some third party; and the voices of this third party were those heard in contention. Let me now advert—not to the whole testimony respecting these voices—but to what was peculiar in that testimony. Did you observe any thing peculiar about it?”

I remarked that, while all the witnesses agreed in supposing the gruff voice to be that of a Frenchman, there was much disagreement in regard to the shrill, or, as one individual termed it, the harsh voice.