Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Myriad Editions

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

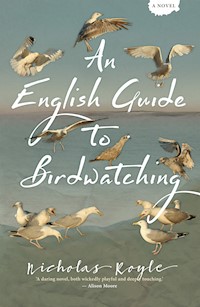

Silas and Ethel Woodlock retire to spend their twilight years by the sea, only to find themselves traumatised by herring gulls. London journalist Stephen Osmer writes a provocative essay about two people called Nicholas Royle, one a novelist, the other a literary critic. Whether Royle, the literary critic, is having an affair with the beautiful Lily Lynch, and has stolen and published Silas Woodlock's short story, 'Gulls', becomes a race to the death for at least one of the authors. Playfully commenting on the main story are 17 'Hides': primarily about birds, ornithology and films (including Hitchcock's), these short texts give us a different view of the messy business of being human, the fragility of the physical world we inhabit and the nature of writing itself. Witty as well as erudite and delightful in its wordplay, An English Guide to Birdwatching explores the fertile hinterland between fact and fiction. In its focus on birds, climate change, the banking crisis, social justice and human migration, it is intensely relevant to wider political concerns; in its mischief and post-modern (or 'post-fiction') sensibility, it celebrates the transformative possibilities of language and the mutability of the novel itself.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 482

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for NicholasRoyle’s first novel, Quilt

‘A book of mythological power. Quilt is unforgettable, like all those great pieces of fiction that are fed by our immemorial root system, the human dream of metamorphosis.’

Hélène Cixous

‘It is quiet, lapidary, and teases out the tangled filaments that link figuration to fact and insight to feeling with the unnerving stealth of a submarine predator.’

Will Self

‘An intense study of grief and mental disintegration, a lexical celebration and a psychological conundrum… Royle explores loss and alienation perceptively and inventively.’

The Guardian

‘Royle’s baroque, athletic prose… confers a strong sense of the “strangeness” of English, “which, after all, belongs to no one” and should be continually reinvented… Moments of delightfully eccentric humour and impressive linguistic experimentalism.’

The Observer

‘A work of remarkable imaginative energy.’

Frank Kermode

‘It is in those commonplace moments at the end of a life… moments which Nicholas Royle describes with such piercing accuracy, when this novel is truly at its strangest.’

Times Literary Supplement

‘What deceptively begins as a more or less realistic piece of auto biographical fiction evolves into an astonishing narrative that puts into question the very notion of everyday reality. A highly readable and stunningly original experiment in literary form.’

Leo Bersani

‘Captures the absolute dislocating strangeness of bereavement. While the novel is bursting with inventive wordplay, Royle’s use of language is most agile and beautiful in his descriptions of rays… The shifts in point of view have a sort of fairground quality to them, suddenly lurching, demanding your compliance, but it is the way the storyline ultimately develops that takes the breath away.’

New Statesman

‘Quilt is one of those books I long for but come across rarely… It is strange, surprising, sui generis… with its overturning qualities, its ability to stick in the head while resisting resolution, and its determination not to leave the reader feeling that the end of the text is the end of the reading experience. What my reading life needs – what the literary world needs – is more Quilts and fewer comfort blankets.’

John Self, The Asylum

‘An experimental and studied look at mourning… Playful, clever and perceptive.’

Big Issue

‘Subtle and eloquent writing… an intelligent and lyrical account of mourning, madness and manta rays.’

Times Higher Education

‘An inventive, risky piece of writing, which succeeds because of the way in which it combines flights of imagination with the sense of a powerful emotional reality.’

The Hungry Reader

‘An experiment, a curiosity… a stirring manifesto addressing the future of the novel itself.’

Booksquawk

Multas per gentes et multa per aequora vectus

In loving memory of

Simon Royle (1960–86)

painter and bird-lover

Happier of happy though I be, like them

I cannot take possession of the sky,

Mount with a thoughtless impulse and wheel there

One of a mighty multitude, whose way

And motion is a harmony and dance

Magnificent. Behold them, how they shape

Orb after orb their course still round and round

Above the area of the Lake, their own

Adopted region, girding it about

In wanton repetition, yet therewith

With that large circle evermore renewed:

Hundreds of curves and circlets high and low,

Backwards and forwards, progress intricate,

As if one spirit was in all and swayed

Their indefatigable flight. ’Tis done,

Ten times or more I fancied it had ceased,

And lo! the vanished company again

Ascending – list again! I hear their wings

Faint, faint at first, and then an eager sound

Passed in a moment – and as faint again!

They tempt the sun to sport among their plumes;

They tempt the water and the gleaming ice

To show them a fair image. ’Tis themselves,

Their own fair forms upon the glimmering plain,

Painted more soft and fair as they descend,

Almost to touch, – then up again aloft,

Up with a sally and a flash of speed,

As if they scorned both resting-place and rest.

William Wordsworth, Home at Grasmere

Contents

PART ONE

The Undertaking

Woodlock & Sons

Silas Woodlock was the end of the line, so far as he was concerned. There would be Ashley, of course, but then that was it. The entire tradition since 1869: kaput. Not that the same building had been home all that time. Still, the sense of history was there. Order, continuity, passing on the baton: one generation to the next. Now it was over. Enough was enough. Things had taken their toll, especially after the scare with Ethel last winter.

If you could call it winter. Primroses popping up in November, spring warmth at Christmas. Catch it in the corner of people’s eyes. Day after day unseasonably mild, as the forecasters liked to say. Imagine the fellow on the weather coming clean: Good evening, once again it was a worryingly unnatural sort of a day, nothing any of us are used to, a day out of sorts with the days we used to think of as days. Daze and confuse, ha-ha. Day after day clement without clemency. Try that. Followed by downpours and flash floods, then bitter weeks of ice and snow, then plunged again into days too mild to be remotely realistic.

Sunday family roast back in the day, coal fire flickering, windows foggy with condensation, clip round the ear if they caught you finger-writing. Dad at the head of the table and Mum bringing in the dishes one by one, steaming hot, and everyone settled and the rest, even the cat and dog, appreciating the order of ceremony. Then the moment impatience became acceptable, the mutt’s eye-whites under the table, the plaintive, semi-smothered yelping for a bone, and pussy in the well’s tortoiseshell arched back and as-if-electrocuted tail curling stiffly through the blind spinney of human legs. And after saying the grace, which never failed to happen at that repast, his old man very formal, as if he had never enunciated the words before, asked would someone be so kind as to supply the seasoning. And Silas and his sisters never thought to wonder what the seasoning was, only something they had to pass down the table for the father to shake out over his roast lamb and veg. It was the old man’s own special mix their mother wouldn’t have touched with a bargepole: salt and black pepper, rosemary and thyme, and other stuff that got stuck in your teeth. Always had to have it with his roast. But Silas couldn’t see what seasons had to do with it, until the last year of school when they studied Shakespeare and Lady Macbeth says to her husband: You lack the season of all natures, sleep.

He could imagine that on his headstone, as a matter of fact. Not that he’d have Ash or Ethel know. But he could picture it, quite poetical, better in the last resort than a line of Latin, fond as he was of that dead tongue. Did Macbeth have the first clue what his worse half was saying? You need some shut-eye is what you need, darlin’. The drift was obvious enough. You lack the season of all natures. Did it matter that no spouse in real life ever uttered such words to their soul-mate? The important thing was that it sounded simple and said more than you could easily ponder. The important thing, he remembered his English teacher saying, was that Shakespeare might have meant season in the sense of a period of time or he might have meant season in the sense of salt or spice and the rest, but it didn’t matter what he meant because we were never going to find out, and in the meantime there was life to live and this magnificent line: You lack the season of all natures, sleep.

Fit for a headstone possibly, but a bit screwball, Silas eventually conceded. Like a message from the dead to everyone still living. A blanket statement to the effect that everyone is suffering from sleep-deprivation. Or as if sleep were the name of a person, as if it were an inscription addressing Sleep itself. As if Sleep lacked all due season. Sleep, you’re out on a limb, mate, you’ve lost all sense and reason. Or then again the statement could be referencing the one who had passed on, inverting the soporific stereotype, called away, at the end of the day, exquisite corpse, the ultimate night-night, gone to sleep and the rest, no, you in the ground there, you lack the season, it’s so far past your bedtime you’re never going to sleep again, this is it, from now on in, sleep no more, no more shut-eye forever.

In any case it was over, pass the seasoning, seasons passed on, farewell Vivaldi, seasons no more. And Ethel being rushed into hospital was the wake-up call. He never quite put it like that to her. He never needed to. It was a wake-up call for them both. They would hand on the business to Ashley and get out of town, retire while the going was good or at any rate still had legs, move out of the giant rats’ nest of London down to the sea. Of course, when they’d been growing up, him and June and Pat, Croydon hadn’t been London at all. Now it was all joined up, crept house to house, street by street, a couple of fields here, a patch of woodland there, overrun, mile after mile filled in with what were a bit sinisterly called developments: retail and industrial parks, car parks, underpasses, flyovers and high-rise sprawl.

It wasn’t that business was bad. Indeed they had done rather well, despite all the change and new competition. Such as the Lady Funeral Director. That was funny. He and Ethel wondered initially was it just for hoity-toity women or what? And then there was the expansion of the black community and other ethnic groups, and different religions coming into the picture. Bespoke parlours of different sorts sprang up. But Woodlock & Sons, convenient in proximity to the register office on Mint Walk, was not like the others. They prided themselves on not having departed from the original family name in all these years. It was still Woodlocks, father and son, on hand to serve all, assisting the bereaved since 1869. As the executive director of another bonafide local family company was on record for remarking: Some large corporations in the ’90s purchased many family funeral businesses, maintaining the family name, thus deceiving the general public. Woodlock & Sons was not like that. It was in the old tradition: International Order of the Golden Rule and the rest.

But no longer. Ashley would keep the business on, of course, but the family-run nature of the thing was coming to an end. Such transformation in so few years! A couple of decades previously, no funeral director in the land had a computer, let alone a website and databases and laserprinters and all the other paraphernalia. With the increased pressure to provide specialism services, from high church to secular, from horse-drawn carriages which the Woodlocks gave up in the early ’80s to the 4x4 and motorcycle events, from gangland to eco-friendly, what a commotion it had all come to seem, what a palaver in the parlour and parlous state of things. Especially with Ethel having had that scare. Rushed into the Mayday or whatever they call it these days, the Croydon University Hospital, and there she was, on the brink, seven days and nights, what with pneumonia and life-support and the rest. The longest week of his life, not to mention hers. Flaming terrible it was, she said, you won’t see me in a hospital again. So they set up a trust arrangement and handed the business over to Ash, lock stock and casket (as his old man used to say), and with the monies released bought not a stately home exactly but a decent little property nevertheless, down in Seaford, East Sussex, in the heart of the old town.

Silas and Ethel had been visiting this stretch of the coast for years, mostly on occasional days out, and once not so long ago for three nights in a local bed and breakfast. They’d developed a soft spot for the town. Compared to its larger neighbours on either side, Brighton and Eastbourne, Seaford was tacky, old-fashioned and unpretentious. It had nothing, besides the elements, that you could call grand. Neither of them had ever lived by the sea and this was a remarkably quiet spot, all things considered. There was a long but walkable esplanade and a shingle beach stretching for a couple of miles in one direction to the port of Newhaven, then trailing off in the other to a golf course and impressive white cliffs. The main row of shops could have come straight out of the ’70s. You could easily get fooled with thinking was that Keith Richards coming out of Bob’s Retro Market, or just an eerie lookalike? The high street had the aura of being stuck in time, placidly indifferent, still in black and white. A couple of the bigger chains had wormed their way in but, by and large, the usual suspects had evidently deemed Seaford just not worth the candle.

Woodlock was drawn, too, by his fondness for second-hand books and vinyl records. The little town had a bustling trade in charity shops, bric-a-brac and antiques, junkshops and old bookshops. It was a great place to spend a few hours, stop for a cup of tea and slice of cake in one of the numerous cafés, mooch about the shops on Broad Street, have lunch at the Old Boot or the Old Plough, the Cinque Ports or the Wellington, then a stroll along the seafront, before heading back to the Great Rats’ Nest.

As the exchange date drew closer, the reality of the thing became almost too much. Ethel fretted:

— What about Ash? Do you think he’ll be alright?

— Of course he’ll be alright. He won’t be all on his tod, after all, there’ll be Jim and the other lads.

— Oh, yes, Ethel vaguely said, Jim.

Their son remained something of a conundrum. He seemed entirely uninterested in getting married or having children of his own. They never aired the matter, but Ethel did wonder if Ash was not of the other persuasion and yet to realise. He was close to Jim. They’d known each other since they were toddlers. Jim had joined them as a pallbearer before he was even out of school. Ethel had her suspicions about Ash and Jim. Not unpleasant suspicions: it can be hard, after all, being a mother and having your only son leave you for another woman. Not that this was much of a topic of talk in the public arena, it seemed to her, but one good reason in her books, why, as a doting mother, your son being gay had its attractions. And Jim was such a nice fellow, not the sharpest knife in the drawer, big but gentle, a bit mentally AWOL at times but flaming heck and pyjamas, who wasn’t, these days? In any case, when it came to working, he was always reliable and courteous.

Of course it’s difficult to be in the funeral parlour game without something to lean on, whether God or drugs or the bottle, and she had more than once caught the whiff of marijuana as they came in on a Saturday after a match (Ash and Jim were ardent Palace supporters) or a night out down at the Green Dragon. But, whatever they got up to, it never interfered with work, and that was good enough for Ethel. She and Silas also liked a drink, it was true. Time was when Silas could really put it away (but not these days). Whereas she would down a couple of glasses of wine and know when she was squiffy and stop. Wouldn’t want to forgo it though. Stem of a glass of cold chardonnay in your hand at the end of the day – few things nicer. In any case, no harm in a pallbearer being pale in the chops and dreamy if that was what it was, in their line of business, from going a bit heavy the previous night. No one ever raised any eyebrows on the subject. Different world from when she and Silas were growing up. Not that she especially liked to imagine her son naked with another fellow. The thrusting and groaning and expletives and everything. Best to let things take their course. So long as they were clean, tidying up properly after themselves. Frankly it was a boon not to know. Even worse, most probably, in the case of another woman.

That was the problem with the world these days. Transparency and accountability, recording and confessing everything. Whatever happened to privacy in all its common decency? The way people share their thoughts and feelings without batting an eyelid with anyone who cares to listen or sign up to their whatever they call it, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, their screensaving social life. Bad enough the amount of paperwork running a family business, doing everything on a screen enough to make you lose your eyesight. And then managing the website. Manage this, manage that. Everyone’s managing. Not. Mostly she left the website to Ash. Not to mention the way everyone was being spied on left, right and centre, every message sent or received, interrupted, intercepted, interception management. What was it all coming to? Somewhere or other down the line, most probably, we’re all on the wrong bus. If her son liked to snog Jim Phillips, far be it from her.

But then one Friday evening, just a month before the exchange date, Ashley came in through the front door of the flat with a pretty young girl. He didn’t seem remotely shy or embarrassed.

— Mum, this is Rhoda, he announced, grinning broadly. I said it would be alright for her to come up.

It was quiet in the Woodlocks’ living room, besides the tip-top, tip-top of the old clock on the mantelpiece. Ethel had thought of it as tip-top ever since her husband once uttered the phrase, a half-tipsy semi-slur that somehow seemed right. Silas disliked television, its tyrannical chewing-gum-for-the-eyes, its endlessly complacent glow. He could tolerate only the news and weather, and even then was inclined to keep up a hostile commentary. She only got to watch when he was out for one of his walks or had gone to his bed. Not that there was anything much on these days. Nothing but soaps full of bad language and unpleasant people. Or whatever they call it, reality shows, same difference. And Silas, though it used to be more regular, now only occasionally listened to his records, usually jazz and blues or, to pep up an evening, David Bowie or the Rolling Stones. But mostly, like tonight, he took to reading after dinner, if there was no job on. He would read for an hour or so, give himself time to digest, before retreating to his bed.

— How nice! exclaimed Ethel, getting to her slippered feet. She felt at once stung and flustered, seeing as she was in her house-clothes, a frumpy top and old slacks. Silas, on the other hand, at first was slow to react at all, caught up, apparently, in an Agatha Christie. Peril at End House it happened to be, and he must have read it at least three times before. What’s the flaming point, she wanted to ask him (but had stopped doing so years ago), reading a whodunnit when you know full well who?

The discombobulation of Rhoda’s arrival got buried in the move, a cold day in mid-January. It was a momentous thing, after all, to up-sticks and start anew down by the sea in the twilight of their years.

— They do say, Ethel said to her husband, as she rummaged for a battered box of Earl Grey teabags on the first morning after, that moving house is the most traumatic thing, apart from death and divorce.

Silas was standing a few feet away in their new living room, surrounded by boxes of books and records, everything feeling displaced and, if truth be told, a bit choked.

— I know, dear, you’ve said that several times in the past month.

— Things will settle soon enough, she observed, as if the retired undertaker had not even addressed her.

Doughty

The sentence he was writing as he hovered over his keyboard, staring at the screen, pursuing the pulsing vertical of the cursor as it left in its wake a new letter, then word, punctuation, space, till the final full-stop, gave Stephen Osmer such an access of pleasure that he died. He skipped off his seat like the carriage on an old typewriter at the end of a line and there he was, tarrying with a convulsion then completely still, on the floor.

He was doing what he had been every day for the past ten days or more, taking to heart the advice of T. S. Eliot: write in the calm of the early dawn. This counsel, given in the privacy of a letter to Lawrence Durrell but set forth with that canny aplomb suited to statements applicable to any would-be writer any time in history, he had long made fun of, keen as he was on cycling and galvanised in the realm of pre-breakfast activities rather by his own twist on the phrase: ride in the calm of the early dawn. Ride or run: for years he had been out, come rain or shine, tracking the empty streets or pavements of London through that eerie period of the morning when, in Wordsworth’s phrase (still oddly apt), the very houses seem asleep.

But for the past couple of weeks he had followed a quite new course. He worked relentlessly through the quietness that suspends central London before the first rumbling of buses, the yawning and electronic voices of delivery vehicles, the interring whoosh of traffic. It was mid-July and the dawn chorus of sparrows had been going on for some minutes. Set up at a little mahogany desk by the window, in his beloved little mews bedsit off Doughty Street, he had wrangled with himself at inordinate length, slowly drinking his first coffee of the day, over the closing section, the final movement as he thought of it, with which he had been preoccupied since Thursday, and then everything gave way. He was reaching for the words, or the words were reaching for him, embarked on the sentence, come upon by an elation unlike anything he had ever felt, a paper ecstasy clanging out of iron agony, his being in flight at the machine, as if silent, the words dropping into place, his eyes flickering between keyboard and screen, then finished.

The funeral was well-attended, despite being out of town. Ben and Jane Osmer had moved to the Cotswolds after Ben took early retirement. She stayed at the cottage, where she had been since hearing the news, like a frozen stalk. Such was the onset of grief, an Ice Age in an instant. No one plans for the death of their children. Ben was a Jew and lapsed communist, Jane the agnostic but devoted daughter of a Church of England vicar. A cremation in Cheltenham was all that could be envisaged. But quite a crowd came down from London, colleagues, admirers and loved ones, friends and relations. Even emerging from the surreal red velvet and brass shadow-show of the ceremony into the blinking light and drizzle, the song of thrushes and blackbirds, the plundering of worms and the green, faintly twinkling, still-dewy expanse of the cemetery was claustrophobic.

Ben made a speech that was even shorter than he had intended. He broke up after less than a minute, like a voice on a phone passing into a tunnel. Passionate about politics at university, his own career beginning at the Morning Star, moving on to promising positions at a couple of the broadsheets, Ben Osmer had had such hopes for his son. He could not say. For his son, he could not say, he – the boy had done well, the boy was going to do – and his daughter Sarah had to stand up and put her arm around him and help him back to his seat. Old colleagues of Ben looked on, pop-eyed in dismay, struggling to smile in solidarity. There was some muffled embarrassed snickering from a couple of Stephen’s fellow workers.

Then Sarah made a short speech, wishing to remember her brother for an inner stillness and purposiveness she would always find inspiring, for his kindness and warmth, for his loving protectiveness. She spoke of how on holiday as children, swimming at Welcombe Bay in north Devon, a sudden cold undercurrent had pulled her feet from under her and was dragging her out and Stephen had realised what was happening and, instead of shouting for help to their parents or others on the beach, swum after her and brought her back. That was what her brother was like.

The editor of the Gazette herself said a few words. She highlighted the tragedy of dying at the age of twenty-seven, what a brilliant young man Stevie had been, what an exceptional future blasted. Another colleague, Brian, hazarded a lighter tone, wanting people to remember how funny Osmer could be. He recounted a couple of cycling anecdotes. There was the time they were walking in Covent Garden, Stephen pushing his bike, in the company of Brian and another friend, both on foot, when Stevie spotted the Guardian journalist the late Simon Hoggart, one of London’s more notorious dislikers of people on bicycles. And Stevie straight away said watch this, mounted his bike and shot out of view, reappearing a minute later round the corner of Catherine Street, deliberately almost colliding with Hoggart, swerving out of his infuriated path at the last possible second. Then, just last spring, there was the time Stevie was waiting at some traffic lights when Russell Brand happened to pull up on a bicycle beside him, and Stevie in a flash dismounted, propped his bike on the kerb and, without any invitation, embraced Brand while declaring loudly enough for Stevie’s companion at the time to catch it on his phone: Mercedes-driving cyclist hug! Yay!

Young Osmer had been employed at the Gazette for almost five years. As a student at Warwick he had been extraordinary, ending up with the top first in his year, or indeed in several years. And then he had stayed on to do a PhD, working on language and class in the later novels of Dickens. But he failed to complete. Indeed he never really started. He read voraciously. He compiled file after file of notes. He knew Our Mutual Friend and The Mystery of Edwin Drood practically back-to-front. He had read more or less every academic article and monograph published on Dickens in the preceding fifty years. He knew everything that was worth knowing about theories of language and society, Victorian England, the history of the novel, Marx, ideology and class struggle. He read around his topic too. Besides all the novels and short stories of Dickens, Stephen Osmer prided himself on having read the collected novels of Wilkie Collins, Hardy and Trollope, not to mention all the Georges (Eliot, Meredith and Gissing). Yet, when it came to putting this knowledge and breadth of reading into practice, he found himself quite paralysed.

As an undergraduate, especially working under exam conditions, he would toss off scintillating essays time after time. It was no bother at all. But as he moved on to his postgraduate studies something closed. He failed to notice. It resembled a sleight-of-hand worthy of late Dickens himself. Initially the supervisor had supposed Osmer’s difficulties were related to the sheer amount of reading he had been doing: in his first year of postgraduate studies he had been left very much to his own devices. The professor had also been one of his undergraduate tutors and was, after all, well aware of Osmer’s intellectual candescence. No one, least of all the supervisor, doubted that this budding young scholar had a great academic career ahead of him.

A supervisory session would consist of an hour’s discussion of, say, Mayhew’s London or the representation of China in Edwin Drood, and the senior academic would be left wavering between intimidation at Osmer’s knowledge and articulacy, and the increasingly pressing obligation to encourage the young man to get his ideas down on paper and draft a chapter or two. Sixteen months went by and still Osmer had come up with nothing. In January he was summoned.

— It’s becoming problematic, Stevie. You’re now a full term late with getting your thesis topic confirmed. If you want to get upgraded to doctoral status you really need to get the outline complete and at least a sample chapter drafted.

But it was futile. Osmer could write notes and even discrete paragraphs without difficulty, but from the accomplishment of a coherent doctoral research outline, let alone a full-length thesis chapter, he was utterly blocked. It was, he told his supervisor (to whom he disclosed very little of a non-academic nature), like riding a bicycle into a sandpit. The professor set him up with some book-reviewing, hoping this might free him from the impasse. Kill two birds with one stone, he thought: get the lad’s writing flowing again, plus notch up some publications for the CV. As it turned out, the release was more dramatic than intended. Following the supervisor’s dispatch of a nicely formulated personal email, Stephen received a request to write a couple of brief notices for the London Literary Gazette. The editor was impressed and asked him down to lunch in Soho. At the end, over espresso, she offered him a permanent position on the editorial team. The young man hardly needed to consider. The following week he formally withdrew from Warwick, to his supervisor’s brief chagrin and longer-lasting relief. They would never speak again. Just ten days after that, Osmer had moved out of his cheap, spacious digs in Coventry into the cramped but charming bedsit in Bloomsbury.

The sentence with which he relinquished his life, nearly five years later, came at the conclusion of an essay about the banking crisis. It was the second full-length piece of prose he produced in his days at the LLG. It was to be a feature article. And that, besides a handful of book notices and off-the-cuff remarks tweeted by others, was his life’s work. The complete oeuvre of the cleverest young man in London boiled down, in the end, to just two essays and a few celebrated aphorisms. The estimation of young writers cut off in their prime, or rather well before reaching it, says something about the vitality of a culture. The value accorded to a few poems by John Keats or Wilfred Owen, for example, is in part a measure of a culture’s capacity to mourn lost art, to recognise the importance of what might have been but never was. It is also a sort of cover-up: the work is quietly smothered under the veil of life. But a culture needs to dream. And when, after all, is a writer’s prime? Hadn’t Sophocles been ninety when he set down Oedipus Rex? And wasn’t Dickens himself in his prime when writing The Mystery of Edwin Drood? Indeed, wasn’t the mystery of that Mystery about the very sense of being cut off in one’s prime, in that case not only regarding the author but the story itself?

All this talk (as there was, in the wake of his death) about cut-off primes: Osmer was no fillet of steak, but neither was he a Keats or an Owen. If youth was crucial, so was the manner of the cut. To take one’s own life, like Plath at the age of thirty, is to invite being snipped from a different cloth. The spectre-thin collateral of war or early-onset tuberculosis can more readily provoke a mourning for mourning itself. But if he was no beef-steak, neither was Osmer merely Gallerte, that mix of various kinds of meat and other animal remains to which Marx refers in Das Kapital in his vicious satire on what it is to be a worker, reduced to sloppy pottage, to be cannibalistically consumed by those who run the show. Osmer was, finally, a writer. For all the paucity of his output, his writing would prove ghostly and enduring. And its effects would still reverberate in years to come.

The first of his essays, on ‘the state of literary culture today’, had been a single blistering all-nighter, modestly revised thereafter, written in early March, just four months before his death. He had been under no external compulsion to write either of the essays. Indeed, that had been one of the great boons of working at the Gazette: he was not required to write. Producing copy was not part of the job description. He soon discovered the tightness, indeed, of the ship on which he was sailing. It was run by a captain who could scarcely countenance anyone besides herself having any significant role to play in any aspect of the operation whatsoever, unless it were in the area of advertising, for which she had indicated, on his very first day in the office, a scathing distaste. In short she was, in Brian’s phrase, a bit of a Grendel’s mother.

As is often the case with monsters, however, she also proved immensely loyal. Stephen Osmer thrived. He had grown up in the dull anonymity of southeast London. To be suddenly plumb in the middle of Bloomsbury was a sort of heaven. And it was to her, also, that he must be grateful for that: a wealthy American contact of hers kept the mews property as an occasional pied-à-terre, and let out the self-contained bedsit at what was, for London, an affordable rate. Stephen had swapped the scrimping miseries of postgrad purgatory in Coventry for the excitement and security of a full-time position at what felt like the global hub of literary and cultural journalism. For the LLG was, after all, a very cool place to be: the most intellectually and politically respectable publication of its kind in Britain, or indeed perhaps anywhere in the English-speaking world. Academics and writers in North America or Australia were just as avid readers and contributors as their counterparts in Islington or Oxford or Glasgow.

And Stephen’s job turned out to suit him very nicely. Besides everyday work on gathering and editing copy, he focused on advertising and events, liaising with the Arts Council, the media, literary agents and festival directors, especially organising evenings involving visiting speakers. This enabled him to have dealings with numerous well-known writers, but also academics, politicians, film-makers and artists. And then increasingly, too, he was given a bigger say, or at least listened to with greater deference, at the weekly editorial meetings, when decisions were made regarding the upcoming issue and the commissioning of essays and reviews for future issues. He lived close enough to the Gazette offices to walk, but he loved cycling around town when he could. And it was a quiet but constant reassurance to be living so close to where Dickens had lived in the 1830s and written Nicholas Nickleby, The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist, among other works. If Osmer had omitted to pay the great novelist the kind of tribute that he had earlier dreamt his doctoral thesis might have been, his attachment to Dickens was as deep as ever.

Mr Osmer was not a handsome man: his hair was already receding in a somewhat disheartening way, his blue eyes were rather close together and his face in general evinced a certain steely superiority which was not necessarily attractive. But he was tall and slender and, like many impassioned cyclists and joggers, emanated a wiry self-sufficiency. This lanky self-composure complemented his eloquence, intelligence and authority of manner and kept him, as it were, in regular girlfriends. He seemed indeed never to settle on any woman in particular, rarely letting a relationship reach its first anniversary. A six-month thing with another Warwick postgraduate terminated when he left Coventry, and just three months into his Bloomsbury job he began a new affair, which soon enough tangled up and gave way to another.

But after three years at the Gazette he met Lily. Lily was a beauty, with hair and eyes of a darkness completely at odds with her name, an enrapturing, luminously beautiful creature just down from Cambridge, three years his junior. She worked for the Arts Council and was clearly headed for great things. People loved working with her. Writers and administrators, fellow office-staff and politicians alike were knocked out. She was dazzlingly articulate, funny and fast. She was flighty and warm-hearted, creative and fiercely independent in her thinking; but she was also, as employers like to say, an excellent team-player. Most of all, she was hot. As noticeable to other women as to men, she entranced more or less everyone she met – and she had chosen to be with Stephen. Having Lily in his life gave him a self-assurance he had not realised he lacked.

Yet still he was a haunted man. He had failed to write a doctorate. He had disappointed his parents, and also himself. He was well into his twenties: Dickens, by his age, had already published Sketches by Boz, The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist. Stephen was, in his own and a good few others’ estimation, the cleverest young man in London. The shining presence of Lily at his side no doubt had a hand in things, but at dinner parties and public events with celebrity authors it was Osmer who provided the most incisive remark, the most compelling critique or memorable anecdote. He continued not to publish anything of his own, besides occasional very brief book-notices for one or other of the rival London literary magazines. These, though few and far between, always commanded respect. But it was his off-the-cuff opinions, his probing questions and impromptu responses that made his reputation. They were repeated by all who knew him, and he was regularly quoted by columnists, bloggers and tweeters. For someone who had never really published anything, he was becoming surprisingly known.

Inwardly, however, three strands twisted ever more tightly. One was an unspoken jealousy of those, especially contemporaries, who had succeeded in writing and publishing creative work – novels, stories, plays. Even piffling poets who had managed to get a slender volume into print he found enraging. Another was his contempt for the self-enclosed nature of academic life. This rancour of feeling had, he knew, intensified since he quit the PhD. And a final braid was anger of a more broadly social and political nature. It was a gathering outrage at the world around him.

The trajectory of anger has its conventions. It rises or boils up. People do not speak of its descent. Yet Stephen felt at moments something of that peculiarity. He saw the world for what it was: a planet entering on a phase of unprecedented anger and turmoil. No feeling of injustice, no sense of egregiousness seemed more charged or meaningful than his own. And this rage, this scorn and indignation, was as much a passage downwards as a mounting up. The body in Old English is the bone-house: something was happening in his foundations. Something broke, at first in a trickle, like a burst water-main pressing through stone, starting with drips then gathering momentum, running down through the brickwork into the cellar of the building.

It was a cold night at the beginning of March. He had arranged to have dinner with Brian at their favourite Turkish restaurant just off High Holborn. He walked briskly, avoiding the blustery exposure of Theobald’s Road, making his way from his flat via small streets and quiet squares.

— Now we’re away from the lair, Brian began, as he watched the waiter setting down glasses and half-poured bottles of beer, how was the visit to old Grauniad land?

Brian was a funny brain. Osmer was fond of him: he was clever and amusing, and had been warm and supportive from the day the Warwick man had arrived at the Gazette. But Stephen also liked to maintain a distance. Colleagues were colleagues. And male friendship, for Osmer, always entailed a dynamic of mutual intimidation. He knew that he was smarter than Brian, and this made it easier to like him. Brian was an Oxford man – Pembroke, to be precise, the place of study of Dr Johnson himself. Osmer had never aspired to Oxbridge, but made it his business to know about different colleges and former famous incumbents. This, he understood, was what the Establishment types themselves did. Any resentment Osmer felt at having ended up for several years at Warwick he had translated into a superior bemusement at what an Oxford education seemed to do to people. Having studied Beowulf, you dutifully inserted allusions to Grendel and the monster’s lair into your conversation. If you had cause to refer to the only – at least faintly – left-wing national paper in the country, you adopted the semi-affectionate, semi-frivolous idiom of Private Eye. ‘Old Grauniad land’ made him wonder if Brian was not in fact an admirer of Tolkien or, just as bad, ex-admirer. But he wasn’t going to go down that path. They had managed to avoid it for nearly half a decade and Osmer had no desire to see that change. Few things got his goat like ‘fantasy literature’. The very word ‘hobbit’, the bilge of ‘Bilbo Baggins’, the vomit-swilling smarm of ‘Silmarillion’ filled him with homicidal contempt. The phrase ‘lord of the rings’ had always sounded to him like some obscene joke or at least to call for one. Lodged in a surreal back-bar of his mind was a dartboard, with the Anglo-Saxon professor’s face miniaturised in the bull. He had taken the train down to Oxford one day, with a new girl from Warwick, and they had found themselves wandering into the Eagle and Child in search of a decent pub lunch, but he’d turned right around and walked out again, the girl following behind him, baffled. At the abject Christian fantasy writers’ parade, all the dreary photos of the deadly Inklings screwed to the walls like works of art in an Italian chapel, Stephen came close, there and then in the Fowl and Foetus, to throwing up.

It was vigorously tweeted at the time: with a single offensive remark, Osmer had stirred chaos at a public reading three nights earlier, at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation in Manchester. Stephen had, frankly, been trying to forget it. But Brian could not resist broaching the topic. The beer was cold, and the hummus with sautéed lamb fillet, baba ganoush and red lentil patties they were sharing as starters whetted the appetite, and the merlot with the main course helped carry Osmer along on an outpouring of vexation that he had fully failed to foresee he might deliver to his friend or to anyone else. He succeeded in keeping Lily out of the picture, but found himself telling Brian far more than he intended. Outside, they stood together briefly on the pavement before bidding one another good night. Stephen’s face was flushed from the wine and sudden cold air, but also from embarrassment at a conversation that had been, more precisely, his long if staccato linguistic monopoly. Brian, however, had enjoyed the evening and said so, before making off in the opposite direction from Stephen, towards Leicester Square.

As he strode up Kingsway then zigzagged, again via the short streets and little squares of Bloomsbury, now more or less deserted, Stephen thought of Dickens walking these same streets at speed, more or less every day, and then at home, frenetically writing. He deliberately overshot, digressing as far as Doughty Street in order to stop in front of No.48. Besides the occasional passing car or taxi, he had the view peacefully all to himself. And the anger of all the decades between Dickens and himself seemed to fill up the night from top to bottom. Looking up into the darkened windows behind which his precursor (not yet Stephen’s age) had written three novels and much more besides, gazing at the doorway through which Dickens had daily passed, Stephen apprehended, with a suddenness that seemed to set quivering the very pavement in front of the house, the force of the phrase at the start of A Tale of Two Cities: recalled to life. Edison’s perfected phonograph came to mind. It was as if the works of Dickens on a series of cylinders were set spinning in his body: he had dropped into a secret recording studio, a pocket of time in which the author’s phrase, by phonographic projection, was sounding through his body. He was recalled to life.

It was as if he had been cycling far harder than he realised and dismounted with a jolt. He might easily have fainted. Perhaps, momentarily, he did. Certainly he was overcome by a wave of coldness, a great gathering-up of numbness, at first in his toes then working its way like early cramp into his lower legs. In his dizziness he leaned on the railings of the house for a moment to steady himself. And a sensation of extraordinary warmth now flooded him. He felt doughty. He felt the meaning of that word in his veins. He made his way back to his tiny mews flat as fast as he could, pulled out his laptop and started to write. Stephen Osmer was doughty. He was recalled to life. He was going to write what he hadn’t written in years. He was going to make a statement about what led up to that outburst in Manchester. And five hours later he had finished. Just before emailing his boss to tell her he was not well and needed to go to bed, he tapped out a title at the head of the document: ‘Double Whammy: The State of English Literary Culture Today’. It duly appeared, a fortnight afterwards, as a lead article in the LLG.

Double Whammy: The State of English Literary Culture Today

We appear to have entered a new era. What remains of England now? What kind of England, however little, however diminished and perhaps pitiful, might be worth holding on to? A book-length discussion of such questions would be in order. I will attempt not to confront them head-on, but instead to illuminate them from a rather specific and no doubt partial angle. I am as susceptible as anyone to the pleasure of waking to the soft tolling of an English village church-clock and the cooing of wood pigeons in the early morning trees, but I am no St-George’s-flag-waving nationalist. On the contrary, I believe that the current surges in nationalistic feeling and self-regard, in England and elsewhere, are toxic to the core. We must oppose and critique the irrational and hate-fuelling forces of nationalistic thinking and beliefs wherever they may arise. The future is not nationalistic but international, as Marx foresaw.

England is one thing, English another. We cannot ignore or wish away the violent hegemony of Anglo-American. It is necessary constantly to grapple with the role played by the English language as capitalism’s lingua franca. This is arguably the writer’s first duty today. At the same time, more than ever, I believe in the capacity of language to transform society and the world. In educational and cultural respects, I would venture to suggest, English is this country’s only remaining important manufacturing industry. Which brings me to my ostensibly narrow and particular question: What is happening with literature and literary criticism in England today?

I want to focus here on the work of just two writers – a novelist and a critic. The former has not long ago published his seventh novel, variously praised as ‘clever’, ‘compelling’ and ‘ingenious’; as ‘a cutting-edge, vital new British novel’; as ‘strange, memorable and, arguably, way ahead of its time’. The latter has not long ago published his tenth book of literary criticism, variously praised as ‘extraordinary’, ‘fascinating’ and ‘exuberant’; as a ‘book that shows the way forward for literary studies’. I should straight away add that these accolades are, as so often, grossly exaggerated. If you believe the blurbs, every day brings another handful of novelistic masterpieces and literary critical groundbreakers. In this respect it should not matter that I have chosen to focus on a couple of mediocrities. You might be forgiven for confusing the novelist and critic in question, for they happen to share the same name: Nicholas Royle. Together they embody everything that is wrong with literary culture in England today.

Initially, like many other people, I did not realise that there were two of them. If you go to an online bookseller or library catalogue you find no distinction made. But on further research it is easy enough to confirm that they are indeed a twosome – one a literary critic and theorist, born in London in 1957, the other a writer of novels and short stories, born in Sale, Cheshire in 1963. The sheer absurdity of two writers with this name! It seems incredible they should ever have put up with it, or that we, the public, should have to do so. I was certainly not alone in doubting they really were different people. Just recently, however, I was able to confirm it, when visiting friends in Manchester and chancing to hear that the Nicholas Royles would be ‘in conversation’ at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation. I went along, and sure enough there they were.

The younger Royle was once described by Harry Ritchie in The Times as ‘specky’. He was also, I discovered, shaven-headed. And he sported, as apparent compensatory gesture, a small goatee. He was, in so many ways, short. A diminutive fellow. And he writes in that manner as well. Short sentences, without verbs. Sometimes. For effect. The older one was a good deal more heavily built. He looked like a worn-out bulldog. He had hair, but this was mostly silver, making him look professorial, just the part for his job: he teaches English, we were told, at the University of Sussex. The two of them together looked ridiculous, like Laurel and Hardy or Little and Large.

I sat at the back where I could get a good sense of the audience as well as gaze at the ‘stars’ of the occasion. The audience thought this pair of Nicholas Royles were funny. People were really laughing. It wasn’t just embarrassment; they genuinely seemed to find the whole thing comical. I don’t know how much the couple had rehearsed what they were doing, but they began with a couple of readings. The younger one proceeded briskly but pleasantly, no-nonsense, in a gentle Mancunian accent. The older one read slowly, lumberingly, in traditional Home Counties BBC English. Then there was a Q&A for about half an hour. There was only one microphone and they stood either side of it, chiming in as they saw fit.

Someone asked how they had met. This gave rise to what one of them called an uncanny story. Everything they talked about came back to the ‘uncanny’. This was evidently the joint declaration of their raison d’être. The fact that they shared the same name and both wrote about weird things, chance encounters, mysterious goings-on: this was ‘uncanny’. Oh, so uncanny. Someone need only say ‘uncanny’ a couple of times for it to start sounding vacuous. I could devote many pages to exposing the follies of this word, and in particular to detailing the fundamental disingenuousness with which it has come to be used in contemporary cultural and intellectual life. Suffice to observe that ‘uncanny’ is a lamentable example of failed thinking, an evasion and a subterfuge. It is a way of pigeonholing alienation while avoiding the reality of oppression. This risible couple had milked the thing and sucked it dry years ago, but were still sucking, like babies, oblivious.

In any case, the older one started reminiscing about a short story he once wrote. I admit this came as a revelation: I had not been aware that he wrote stories as well. The old woodlouse had sent a thing off to a magazine – this was back, he said, in the late ’80s – a magazine called Sunk Island Review. He said that when he got his customary rejection letter (more audience laughter here) his attention was arrested by an odd detail. The editor turning down his story had addressed him as Nick, whereas he had used his full forename when submitting the piece. Also, the editor referred to being ‘unable to use either of these pieces at the moment’; Royle had submitted only one story. But then he noticed that there was another typescript enclosed. This other typescript bore the title ‘Flying into Naples’ and the authorial name ‘Nicholas Royle’, along with an address somewhere in Shepherds Bush. Sunk Island Review was rejecting both Nicholas Royles. So Royle was then in a position to send on the misdirected story, as well as have the strange satisfaction of conveying the news of rejection to its rightful recipient.

Again, this anecdote solicited a good deal of tedious laughter. As if suddenly waking up to the reality of the occasion, the older one, the literary critic, remarked that they seemed to be a double-act. People practically fell off their chairs at this. And then the other one flamboyantly ‘copped on’ that they had not actually answered the question as such, about how they first met. Why was that felt to be amusing? It must have been the homoerotic frisson as well: there was something histrionically ‘romantic’ about their parading together in the public eye.

— We didn’t actually meet, though, till some years later, did we, Nick? (The audience quietened down again for this.) We exchanged letters and then emails.

— That’s right, said the critic. We only met for the first time in 1997, at Senate House, in London. I was giving a paper on the subject of the double (some chortling here) and I talked about Nick’s novel, The Matter of the Heart. No one else in the audience at that time knew that the novelist himself was in the room. We’d agreed in advance that we would meet – literally for the first time, shake hands with one another – at the end of my lecture. Nick was to stand up, we were to walk towards one another and shake hands, and then he was to make his way round and sit in my place and respond to questions.

— It was funny, chipped in the little one.

— It was awful, said the larger one. (Audience laughter.) It was completely unexpected. It was the longest, most troubled silence I have ever experienced. After a couple of minutes someone spoke up: This is taboo. This shouldn’t happen. And Nick and I realised it was true. There was something truly discomfiting about it, but we hadn’t seen it coming. When you give a lecture on someone’s novel it’s not appropriate to reveal to the audience at the end that the author is actually in the room and will now take questions.

— A bit, er, uncanny, said the younger Nicholas Royle. (This, to a mix of hearty and uncomfortable laughter. You didn’t have to be a Freudian to pick up the ambivalence: the audience could take only so much of all this ‘uncanny’ nonsense.)

And this prompted the novelist to recall another coincidence. It had to do with the fact that his first book, Counterparts (1993), appeared around the same time as the literary theorist Royle published a critical monograph (co-written with Andrew Bennett) about the novels of Elizabeth Bowen. At which juncture, unbeknownst to the other, each Nicholas Royle sent a review copy of his book to the then largely unknown Jonathan Coe. Allegedly weirded out by the simultaneous arrival of two books by strangers both called Nicholas Royle, each containing (one imagines) some sycophantic missive asking if he would consider reviewing the book, Coe felt he had to write something about at least one of them. His review of Counterparts duly appeared in The Guardian shortly afterwards, and the Mancunian novelist’s career was launched.

I have to confess that this dropping of Coe’s name into the conversation was the final straw. It was an entertaining enough evening, I suppose, and the Royles could count on selling numerous copies of their books after the event. But it also seemed to me troubling in ways that the dynamic duo completely failed to understand. Certainly the venue was significant. The building was a restored nineteenth-century warehouse, a huge interior of warm exposed red brick, mostly paid for by the success of Burgess’s novel, A Clockwork Orange