Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

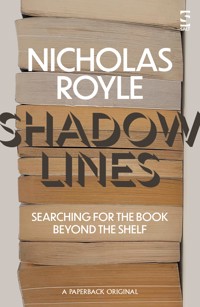

'Shadow Lines very much celebrates the world of books' —Telegraph Nicholas Royle's love of second-hand books and the 'inclusions' he finds inside them, their presence betrayed by 'shadow lines', is about making connections. Someone has scribbled a number in a book? He'll text or call. An old address? He'll return the book to where it used to live. Follow him as he walks between bookshops, reading as he goes, on the hunt for treasure, for ways to make us feel closer – to the books on our shelves, to each other and to our own lives. Share in Royle's enthusiasm for the Rev W Awdry's Railway Series, Penguin Modern Stories and Paul Auster's cult classic, The New York Trilogy, as well as books in art and film. The brilliant follow-up to the instant classic, White Spines. Praise for Shadow Lines ★★★★★ 'What links Bin Laden's bodyguard to an Oxfam bookshop in London?What links Bin Laden's bodyguard to an Oxfam bookshop in London?. In Shadow Lines, Nicholas Royle tracks down the owners of objects slipped into second-hand books – with amusing and surprising results.' —Ian Sansom The Telegraph If you love books, bookshops and browsing, this is your perfect all-year gift – head to your happy place with a copy Shadow Lines today! (Note: 'inclusions' not supplied.)

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 355

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iiiiii

SHADOW LINES

Searching for the Book Beyond the Shelf

NICHOLAS ROYLE

For Gareth Evans

‘I love you more than words can tell.’

Unsigned note found inside Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho bought from Oxfam Books & Music Islington, 1 October 2023

Contents

Introduction

I said to my publisher that I wanted to do a follow-up to White Spines. He said, Sure, go ahead, but make sure it doesn’t feel too much like a follow-up. Sequels never do as well.

I thought of The Godfather Part II and Terminator 2: Judgment Day. I thought of Paddington 2. I didn’t think of Aliens, because Aliens is a vastly inferior film to Alien, and you are free to disagree, but I’m not going to change my mind. Even Alien³ is better than Aliens and Alien³ is not very good.

I am aware that this is a book, not a film.

White Spines had a narrative: the edge-of-your-seat story of my quest to collect all the white-spined Picadors published by that publisher between 1972 and 2000, when they abandoned the classy look that had been more or less a guarantee of quality.

This book, Shadow Lines, would be different. It would make a virtue of not having a narrative. It wasn’t that I couldn’t think of one. I toyed with various exciting plotlines – the hunt for all the white-spined King Penguin paperbacks published between 1981 and 1987; the quest to collect all the white-spined Paladin paperbacks published between 1986 and 1992; the search for all the white-spined Sceptre paperbacks published between 1986 2and 1994 – and rejected them all. I do collect those books, as well as the white-spined paperbacks of Abacus and Vintage and Black Swan, but I wanted the new book to be more than a find-and-replace job.

I wanted to write about my collection of the Rev W Awdry’s Railway Series stories, and, more to the point, about the illustrations. Everyone, I imagine, who has any interest in Thomas the Tank Engine and friends, has their own favourite illustrator. I wanted to write about mine – C Reginald Dalby – and the connections I started to see between his work and the paintings of the great Belgian surrealist René Magritte.

I wanted to write about the Penguin Modern Stories series of anthologies from the late 1960s and early 1970s edited by Judith Burnley, not to be confused, despite the fact that in my head I do it all the time, with author Julia Blackburn. I will try not to do it in this book.

I wanted to write more about what I call ‘inclusions’ – ephemera found within the pages of second-hand books, like insects in amber, which are known as inclusions – and how they have become often more important to me, in my collecting, than the authors, titles or printed contents of many books. I wanted to write about how I find them, by means of what I call ‘shadow lines’. I wanted to write about books in which people have scribbled phone numbers. I wanted to write about books in films and books in the work of installation artist Mike Nelson.

I wanted to write about walking and reading, about people I see doing it and the books they are reading, and about my own decades-long compulsion to do it, too, and about the books I am reading when I am doing it.

I realised I was acquiring – and keeping in my home – books that perhaps ought to be in other homes. I wanted to write about 3some writers I have known who have died. I wanted to vent about one or two things. I wanted to write about a cult classic that I first read in the late 1980s and see if I still think it’s the masterpiece I thought it was then. I also wanted to share some more of my overheard conversations in bookshops and dreams about books. These will be dropped in here and there.

The search for the white-spined B-format Picador paperbacks published between 1972 and 2000, which provided the main focus of White Spines, is ongoing.

Visiting family in Shrewsbury on a Saturday in July 2021, I went for the first time to Welsh Bridge Books & Collectables, an excellent shop that sprawls over three floors of a very old building – ‘MIND YOUR HEAD’ – with an interesting selection of books. One section is devoted to Beat writers. There were titles by Kerouac and Burroughs and, to my great delight, a Picador I hadn’t known existed, Kentucky Ham, by William Burroughs Junior, marked ‘RARE’ and costing only £2. I’m not even sure I’d known that William Burroughs Junior existed.

I’m not sure either how after that I ended up in Erotic Literature, but it was there that I found Trevor Hoyle’s The Hard Game (New English Library). I’m a fan of the string of novels Hoyle published with John Calder – Vail, The Man Who Travelled on Motorways and Blind Needle – which might be characterised as experimental or speculative. (Blind Needle was the first book I was commissioned to review for the Guardian, although the review never appeared.) Wikipedia describes Hoyle as a science fiction author; The Hard Game appears to add yet another string to his bow.

After we had exhausted Welsh Bridge Books & Collectables, my wife’s brother-in-law took me to the lovely Raven 4Bookshop in Shrewsbury’s Market Hall, where I added Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights to my collection of Virago Modern Classics, and a Raven Bookshop badge to my collection of button badges. Finding Candle Lane Books closed, we called in at the Oxfam Bookshop, where I found Rilke’s The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge (Picador Classics) and Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry (Fitzcarraldo Editions). Hatred is a strong word, but I didn’t enjoy Lerner’s first two novels, Leaving the Atocha Station and 10:04, enough to make me want to read his third, The Topeka School. As for this slim volume of non-fiction, I was curious to find out if I would like Lerner more if he turned out to hate poetry (despite being a poet and a poetry editor).

I have now read The Hatred of Poetry and couldn’t actually tell you what is Lerner’s opinion of poetry.

I found three new-to-me Picadors in one place in Carlisle. Anyone who knows their second-hand bookshops will know specifically where in Carlisle.

Where else but Bookcase? I’d gone there – to the bookshop’s café, Cakes & Ale – to meet artist and Picador cover illustrator Paul Leith and as a bonus he had brought along his lovely wife Tina. We had coffee and rainbow cake, and found we had a few acquaintances in common, such as Paul’s fellow book cover artist John Holmes (who I never actually knew, but I had been in contact with his family over the proposed use of two of his images) and artist and figurative painter Andrew Ratcliffe (who had been my art teacher at school). In the shop I found three books with covers by John Holmes – Ivy Compton-Burnett’s A Heritage and Its History, Vladimir Nabokov’s Quartet, and Possible Tomorrows edited by Geoff Conklin – and three Picadors not among my collection – Stacy Schiff’s Véra (Mrs Vladimir Nabokov), 5Tony Parker’s The People of Providence and Ajay Sahgal’s Pool. I picked out another Picador, Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics, with a cover by the Brothers Quay, previously owned by a Bernard Fison. It struck me as an unusual name; I looked him up.

A retired stockbroker, Bernard Fison sailed his yacht around the world, before returning to his family’s holiday home in the Cumbrian village of Boot and subsequently making Boot his permanent home. Singing in a local choir, taking art classes and becoming a church warden, he lived village life to the full, while at the same time raising money for the poor of Sri Lanka, where he had been shown great kindness on his round-the-world trip.

In 2007, he was involved in a serious four-vehicle accident on the A595 and died at the scene, leaving a son, two daughters, a brother and a granddaughter.

Now, thanks to Bookcase, I have his copy of Cosmicomics – and his 1000 lire note, bearing a picture of another world traveller, Marco Polo, which I found tucked inside at page 59. In a coincidence that Calvino would perhaps have enjoyed, the only other Italian currency I have found in a second-hand book was also a 1000 lire note, also with Marco Polo, in a 1987 Paladin edition of The Wine-Dark Sea, a 1973 short story collection by Calvino’s contemporary, Leonardo Sciascia, with a striking cover by the great James Marsh. The banknote in The Wine-Dark Sea had been inserted at page 61.

In October 2018 a new second-hand bookshop, Yum Yum, opened in Tib Street, in Manchester’s so-called Northern Quarter. I failed to write about it in White Spines, although I thought that I had. At some point over the next two years, it changed its name to Anywhere Out of the World. The last time I saw Louis, the young man who dared to open a bookshop when more people were closing bookshops than opening them, 6he was sitting barefoot on his couch in the middle of the shop declaring that he was retreating from the world of the senses into a world of interiority. Since then, however, the business has expanded. Expect great things.

Talking of great expectations, I was in upstairs in Richard Booth’s Bookshop in Hay-on-Wye on Wednesday 4 August 2021 when I became aware of a hubbub at the far end of the room. I heard the end of a brief speech, an announcement, a burst of applause. I gathered that a young couple had just become engaged. He talked about having pinched a ring so that he would be able to order the correct size of engagement ring. She said something about the bookshop. It seemed that maybe they were connected with the shop in some way. Perhaps they had worked there, or perhaps still did. I hope they enjoy a long and happy life together.

Amid the excitement I found some good books, at Hay prices, some of them. Marguerite Duras’s Le ravissement de Lol V Stein (Folio) with the name of a previous owner, Damien Bertrand (juin 1988), and an inclusion, a business card from a restaurant, Michel Chabran in Pont de l’Isère. Another French book, Monique Wittig’s Virgile, Non (Editions de Minuit), withdrawn from the library of the University of Sheffield. A Sceptre first novel, Watercolour Sky, by William Rivière, two novels by Anita Mason – The Racket (Sceptre) and The War Against Chaos (Abacus) – and a Picador with a horrible brown-speckled white spine, Tama Janowitz’s American Dad, which I will try to replace with a non-speckled spine. It looks like they were aiming for rag-roll and got bog roll instead.

On an honesty shelf in an alleyway I found The Picador Book of Modern Indian Literature edited by Amit Chaudhuri, published in 2001 but with the old white spine. This was very 7exciting for me, because previously the latest iterations of the white spine I had seen, and bought, had been from 2000.

A week or so earlier, I had been to Sharston Books, in south Manchester, for what I thought would be my last visit. Novelist and short story writer Neil Campbell was still working there, but he was on notice; by now the shop was closed to customers and open for online orders only. Neil let me in. Among many other interesting finds I came across another Marguerite Duras, in translation (by Barbara Bray), Blue Eyes, Black Hair (Flamingo), a copy previously owned by ex-Factory Records boss and Manchester impresario Tony Wilson, who had used the inside back cover to write out a ten-point plan of action. Point one was ‘Create new entity’. Point four, ‘All rights transferred to the new entity’ etc.

In fact, Sharston Books limped on into 2022. On Sunday 29 May 2022, I saw on Facebook, at 1pm, that Sharston Books would be open that day, for the last time, until 2.30pm, so I walked down to the river, over Simon’s Bridge, around the golf course, down the various paths and arrived to find the gates locked, and a woman indicating that I should go around to another entrance. A sad sight awaited me. Most shelves cleared. Classics gone. A young man behind the desk playing on his phone. Upstairs, miles of empty shelves. In the shipping container devoted to fiction I picked out ten for a tenner, including one with a good shadow line.

When you are looking down on the top edge of a book block – the pages of a book that have been glued or stitched together to form a single unit – and you see a line of shadow that suggests that within lies treasure, be it a train ticket from London to Tiverton Parkway dated 12 April 2001 inside E Croxford’s copy of Ruth Brandon’s Surreal Lives or a birthday card from Anita to Bernard in Dashiell Hammett’s The Dain Curse in which Anita 8has written, ‘The first of many together’, that line, that parting of pages, is what I call a shadow line.

Daphne Merkin’s Enchantment (Paladin) had a strong shadow line near the end of the book – page 241, I saw, when I removed it from the shelf and opened it and found a little stash of nine children’s drawings. If the former owner of this book were ever to read this and want them back, nothing would give me greater pleasure than to return them. The same goes for any inclusions that I describe in this book.

Although I write somewhere in these pages about how finding books that you are missing from a collection out in the wild is more exciting than being given them, the generosity of friends and strangers who have given me Picadors, and other books, must be acknowledged. I have experienced the pleasure of giving, and the pleasure of receiving should begin with an appreciation of the act of giving. So, thank you to David Batt, without whose offer of two Picadors he knew I didn’t have – Richard Klein’s Cigarettes Are Sublime and Joe Queenan’s Imperial Caddy – I would almost certainly never have entered the doors of Brooks’s Club, St James’s, where I went to pick them up. On the way there I had called in at the Skoob Books pop-up in the Brunswick Centre where I had found another Richard Klein title, Eat Fat, which had also eluded me up to that point. And on the way to Skoob, I had popped into Oxfam Books & Music Islington and spotted the faintest of shadow lines on the top edge of a Livre de Poche edition of Amélie Nothomb’s 2010 novel Life Form, revealing a to-do list that I hope it is not too indiscreet to reproduce here:

Card for Penny

LSO sing-in – book

Food for lunch/Sonia 9

Plan Sun lunch

email Bridget

Letter – Zara (re pyjamas)

Hackney vouchers

email Carla/Billy

email Gill

write Sally

Phone scaffolding

French h/work

CQ to bank

Band

Impressively efficient – I have no doubt that Sunday lunch was eventually planned, but I’d love an update on ‘Letter – Zara (re pyjamas)’ and I hope the author of the list had more luck with Zara than I did with Uniqlo when trying to exchange an item with a receipt but without the price tag (which incorporates a computer chip).

I have lost count of the number of Picadors given to me by Gareth Evans. On a Saturday in October, 2021, he gave me a copy of The Dispossessed by Robert McLiam Wilson and Donovan Wylie. The same day, I had been, with my wife, to Brighton and we had visited the Smallest Bookshop in Brighton, which on that day took the form of a stall on Brighton Open Market. Proprietor John Shire had emailed after reading White Spines to say he had a copy of The Freud/Jung Letters edited by William McGuire and abridged by Alan McGlashan that he would put aside for me. My wife picked out Mary McCarthy’s The Groves of Academe (Panther) and I also selected a first edition of Frights (Gollancz) edited by Kirby McCauley. When Frights went into paperback it was divided into two volumes and I only have the 10first one, which doesn’t include Robert Aickman’s story, ‘Compulsory Games’, or for that matter stories by Ramsey Campbell and Dennis Etchison. Frights and Mary McCarthy, along with The Freud/Jung Letters, came to £14, but John sold them to me for a tenner. That’s my kind of second-hand bookseller.

Two people each gave me a copy of Gilbert Sorrentino’s Mulligan Stew, both expressing surprise that I hadn’t already got a copy, but due to what I can only call a cock-up on the record-keeping front, I can’t say who either of these people was.

Sometimes, although not very often, I see a book I would like to buy – for its inclusion or inscription, perhaps – but don’t.

At 5pm on a Saturday afternoon in December, 2022, I was making my way through the crowds in Portobello Road when I spotted a book stall on the market. I had a look. Lots of stock, including Picadors and ghost story anthologies from the 1960s and ’70s. I picked up a Picador and quickly put it down again – £10 for a Picador? Don’t make me larf. I picked up The Fourth Fontana Book of Great Ghost Stories edited by Robert Aickman. I collected this series years ago – alongside the Fontana Book of Great Horror Stories and Pan Book of Horror Stories series – and had always been missing one volume, the fourteenth, until I found it in Oxfam in Durham in June 2022 for a couple of quid. Pencilled on the flyleaf of this copy of the fourth volume was the price: £25. Twenty-five big ones? Cor blimey, strike a light, guvnor! Talk about ripping off the tourists. More interesting to me was what was written in green ink on the inside front cover. ‘A present from my brother. This book belongs to Melanie Boycott.’ I took a picture, glowered my intense disapproval towards the stall generally and melted back into the crowd.

I found a Melanie Boycott on Etsy and sent her the picture 11I had taken of the book and a short message. Later, Melanie replied by email. She was the same Melanie Boycott; it had been her book. ‘I’ve travelled around a bit, since I owned it,’ she wrote. I explained that had it been a couple of quid, I would have bought it and sent it to her, but that it was ridiculously overpriced. ‘My brother would have got me that when we lived in Barnsley,’ she continued. ‘It was a time you all had to have a fountain pen for school and I had a bottle of green and a bottle of purple ink.’ I, too, used green ink in my school exercise books, green and turquoise.

Melanie went on: ‘We then moved to Tywyn in Gwynedd and from there I went to Sheffield Polytechnic. After staying in Sheffield for a while I moved to Skipton where my mum and dad had a caravan.’

By now, if things have gone according to plan, Melanie should have moved to Earby in Lancashire, but historically part of Yorkshire. Her son, she told me, lives in London, but otherwise she has no connection with the capital. Apart from that outrageously overpriced copy of a book her brother gave her.

In August 2021, in Oxfam Books & Music Islington, I found a lovely Penguin Modern Classics edition of Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds with a wraparound cover that reproduces The Bus by the River by Jack B Yeats. On the inside front cover in distinctive, almost Gothic, handwriting, in purple ink, is the name Penny Ashbrook, followed by ‘Manchester 1973’. On the facing page, the flyleaf, in tiny handwriting in the top-left-hand corner, close to where, sadly, the jacket is starting to come away from the book block, we read, ‘8 for £1.’

At page 141 there is an inclusion, a theatre ticket designed to look like an old £1 note. ‘From Edinburgh,’ it says, ‘At Swim-Two-Birds. 12Christ’s Theatre. 8.30pm Oct 16th–20th.’ The price given is 35p.

Only in November 2023 does it occur to me to ask novelist and short story writer John Ashbrook, who I know, and whose partner Elizabeth Baines I also know, because they live near me in Manchester, whether Penny Ashbrook might be any relation. In fact, I ask Elizabeth, and she tells me that Penny is John’s daughter and, although she lives in New Zealand, she is staying with them at the moment. In 1973, Penny was in Cambridge, but was coming and going between Cambridge and Manchester. After that she lived in north London before moving to New Zealand in 2004, where she works as a TV writer, director and producer.

Frustratingly, in November 2023, I can’t find my copy of the book and was working from my notes relating to its purchase in 2021. I find it on a wet and windy night in January 2024, the night before I am due to deliver the manuscript of this book (the latest – and definitely the last – in a series of deadlines). There’s no reason why Penny should want the book back – she gave it away, after all – but it might be fun to see it again, and if she has returned to New Zealand, maybe John would like to see it. He can either keep it or give it back to me.

I slip the book into a padded envelope and head out into the night.

1

Reginald the Surrealist Engine

In the first episode of the new era of University Challenge, presented by Amol Rajan and broadcast on 12 July 2023, the new question-master asks the team from Trinity College Cambridge the following bonus question: ‘A murderer at the scene of his crime and two bowler-hatted men armed with a club and a net feature in which painter’s 1927 Surrealist work The Menaced Assassin?’ It’s the detail of the bowler hats that allows the Trinity team to answer, with confidence, ‘Magritte.’

Three years and one fortnight earlier, on 27 June 2020, just days after non-essential shops were allowed to reopen following the first national Coronavirus lockdown, I came off the M6 at Coventry, parking on Brighton Street in Upper Stoke. Or is it Barras Heath, or perhaps Ball Hill? I don’t know, but the key thing was I was at least a mile from the centre of Coventry and parking was unrestricted. Plus, there was a good stretch of road with back gardens on one side and a high privet hedge on the other: I could park without inconveniencing anyone. Indeed, no one was actually parked here. There didn’t appear to be anyone around at all. I walked down towards Walsgrave Road, a high brick wall having appeared on my right to shield local 14residents from the noise of the traffic on Jimmy Hill Way. At Gosford Green I turned right and walked along Far Gosford Street, heading towards the Big Comfy Bookshop and hoping it would be open. I had done my research, which suggested it was supposed to be, but in June 2020 we were all more used to seeing shops closed than open.

It was open and it turned out to be a good bookshop to visit immediately post-lockdown, because it had a generous amount of floor space – concrete, painted red, if you want to know. There were even armchairs, also red, but they were taped off. ‘CAUTION,’ shouted the yellow plastic tape. ‘ATTENTION.’ My eye was caught by a more welcoming, handwritten sign affixed to a shelf of old books. ‘OLD BOOKS,’ it said. ‘Is there any better smell than that of old books? Come and browse for a while, you never know what you might find.’ I found a novel, in hardback, The Exhibitionist, by Henry Sutton. I could see that it couldn’t possibly be by my contemporary Henry Sutton, author of The Househunter and Flying and numerous other novels, unless he had been a child prodigy and written it when he was four. I decided to buy it and write to Sutton and ask him if he knew about it, maybe offer to send it to him if he was interested, and was about to head with it to the till when on a low shelf I spotted a short, slim black spine, title in white, Bodoni Ultra bold italic – that wasn’t the title, that was the typeface. The title was Toby the Tram Engine. Or:

TOBY THE TRAM ENGINE

If you can imagine that white out of black.

In fact you don’t need to. 15

TOBY THE TRAM ENGINE

I read it while walking back to the car. Toby the Tram Engine is number seven in the Railway Series of books by the Rev W Awdry, first published in 1952, but the reprints I collect are from the 1960s and ’70s, as they remind me so strongly of my childhood. I love everything – well, almost everything – about them, from the typeface on the spine and front cover, to the small format, the very fact of their being a numbered series, and of course the stories themselves. But, most of all, I love the illustrations, which, as I hope to show, are not just engines with pretty faces, but evidence that the ambition of one of the Railway Series artists extended way beyond the island of Sodor.

There was tension and conflict on the railway, however, and not everything ran smoothly.

The first book in the series, The Three Railway Engines, was first published in 1945. Awdry had written three stories for his young son, Christopher, and, with his wife’s encouragement, had submitted them to publisher Edmund Ward in 1943. A fourth story was requested and this set the template for The Three Railway Engines and the next twenty-five books in the series, all written by Awdry, the last of these, number twenty-six, appearing in 1972. Eleven years later, Christopher Awdry took up his pen and added a further sixteen books to the series.

The first edition of The Three Railway Engines was illustrated by William Middleton. Awdry was unhappy with Middleton’s work and it’s easy to see why – the features sit rather flatly and sketchily on the moon-like faces of the engines – and he was replaced for the second book, Thomas the Tank Engine, by Reginald Payne, whose style was livelier and more vivid, the faces more 16expressive. Sadly, however, Payne suffered a nervous breakdown and was himself replaced for book three, James the Red Engine, by C Reginald Dalby, who also redid Middleton’s illustrations for later editions of The Three Railway Engines and made a number of alterations to Payne’s work on Thomas the Tank Engine – Thomas backs into a station instead of facing forwards; extra luggage appears on a platform; telegraph poles and a signal gantry are added to countryside scenes; a water tower gets a different pipe; and a van changes colour from green to brown – although my edition, dating from 1969, does not credit either illustrator.

Dalby would remain the series’ illustrator until (and including) book eleven, Percy the Small Engine, in spite of Awdry’s increasing dissatisfaction with his work as well. The author complained that Dalby’s illustrations were inaccurate and inconsistent. When we see, for example, in Tank Engine Thomas Again, Henry standing at a platform, still in his blue livery that he had been given at the end of the first book, but with square buffers and two side windows in his cab, instead of round buffers and one side window, in other words looking exactly like Gordon, who is also blue, it is hard to disagree with Awdry. There was further inconsistency in Henry’s wheel arrangement: originally drawn as a 4-6-0 locomotive, he would sometimes appear as a 4-6-2 engine. Don’t worry if you don’t know what these mean; trust me, it’s an inconsistency.

When Awdry described Percy, in the eleventh book, Percy the Small Engine, as resembling ‘a green caterpillar with red stripes’, Dalby, a successful commercial artist and the creator of the famous Fox’s Glacier Mints polar bear logo, packed up his brushes and refused to illustrate any more Railway Series books, citing late delivery of scripts as the reason why.

‘I was sorry to give up,’ Dalby is quoted as saying, or writing, 17in a video posted on YouTube by ClickClackTrack. ‘I had become intimately involved with my engines, their characters and personalities; but, like that other famous “artist” Adolf Hitler, my patience became exhausted.’

If Dalby did say, or write this, you have to think it’s an unwise and somewhat baffling comparison to make, but when I look at the raised right arm of the vicar in the final illustration in Percy the Small Engine, I wonder if he was playing a long game. He certainly seems to have found Awdry – who, let’s not forget, was a reverend – pedantic and difficult to work with, while the relationship between the two men might have been doomed from the start. When original Thomas the Tank Engine illustrator Reginald Payne had gone AWOL, Awdry had done some sketches of his own for book three, in collaboration with his friend Barbara Bean, but when he sent these to editor Eric Marriott, the answer came back that an artist, Dalby, had already been engaged. One can imagine even a cleric’s nose might have been put out of joint.

Dalby was replaced by John T Kenney, whose colours were a little less bright, most noticeably in the green livery worn by Percy, Henry and Duck, but who enjoyed a good working relationship with Awdry and was only replaced after book seventeen, Gallant Old Engine, when his eyesight began to fail. For book eighteen, Stepney the ‘Bluebell’ Engine, the commission went to Swedish artist Gunvor Edwards, who asked her husband Peter to assist her and they shared the illustration credit until book twenty-six, Tramway Engines, which was Awdry’s last. Their style was more impressionistic; to me, the faces look all wrong, perhaps because the first faces I had seen had been Dalby’s and so those, to me, were the originals, the real faces, imprinted on my mind, and any that came later were inauthentic, unconvincing, poor substitutes. 18

For similar reasons, perhaps, actual trains today seem to me more like plastic toys than real trains. Which is not to say I miss the days of steam; I had to go out of my way, to the Keighley and Worth Valley Railway, for example, to encounter steam, or happen to be on York station when Sir Nigel Gresley called by with a special. The trains that moved me were the AM4 electric multiple units I would travel on as a boy from Altrincham to Manchester Piccadilly; the Class 25 diesel locomotives and Class 40s and occasional Type 3s and Brush 2s that I would see pulling goods trains through Skelton Junction; the Peaks I would cop, or even cab, at Piccadilly as they stood waiting to pull the Harwich Boat Train; the Class 76 electric locos I would goggle at, at Guide Bridge, with their widely spaced window eyes and diamond-shaped pantographs (yes, I was a trainspotter, in case you hadn’t guessed). These were, and remain, real trains, because they were the trains I encountered at an impressionable age, when my mind was like the grey putty in Magritte’s painting The Reckless Sleeper, which may not be a perfect analogy, because the grey ‘tablet’, as the Tate website calls it, in the Belgian Surrealist’s 1928 work, probably represents the sleeping mind, but the way those symbolic ‘everyday objects’ – mirror, bird, bowler hat, bow, candle and apple – are ‘embedded’ in it suggests to me an act of imprinting.

Today’s trains, while they might get me where I’m going in a shorter time, don’t seem altogether real and an after-effect of lockdown, once we were permitted to travel again, was to put more people back in their cars and fewer on trains.

On 22 September 2020 I was driving up the M1. I left the motorway at junction 14 and skirted Newport Pagnell, parking a mile out of Olney and walking back in to visit the Oxfam Books & Music. It was quite a small shop and I found nothing I 19wanted until I spotted a battered copy of The Time Out Book of Paris Short Stories (Penguin). I edited this anthology for Time Out, but have few copies, so I thought I’d buy it rather than leave empty handed. Plus, it had an inclusion, but one of the least interesting ones I’m sure I will ever find, a tiny scrap of brown envelope with sealing gum on one side, tucked in at page 45, the first page of Toby Litt’s ‘Story to Be Translated From English into French and Then Translated Back (Without Reference to the Original)’. Whatever music had been playing over the Olney shop’s music system switched to Van Morrison. Following his recent pronouncements on the subject of Covid 19, I thought I could do without Van Morrison, so left, walked back to the car and drove north, heading for Market Harborough. Again, I parked out of town and walked back in, again, to visit the Oxfam Books & Music. It somehow didn’t feel, as Olney hadn’t, that it would prove to be a treasure trove on a level with Harpenden, say, or St Albans or the fabled Berkhamsted shop. All I found was Edward the Blue Engine, book nine in the series, so one of those illustrated by C Reginald Dalby. Again, I read it as I walked back to the car.

Readers may know that Thomas the Tank Engine and his friends inhabit the fictitious island of Sodor located between the Isle of Man and mainland Britain. Wilbert Awdry was born in Romsey, Hampshire, in 1911. His father was Vicar of Ampfield and many of his parishioners were railwaymen. He would visit them, at the station and at their platelayers’ huts beside the railway, and sometimes he would take his son along. In 1917 the Awdry family moved to Box. It is said that the young Wilbert would lie awake in bed at night listening to trains effortfully climbing the hill to Box tunnel and he would imagine that they were talking to themselves. ‘“Can I do it? Can I do it? … 20Yes, I can. Yes, I can.”’ Awdry, a lifelong railway enthusiast and keen railway modeller, would later say that most of the stories in his Railway Series were based on real events. And some of the characters were based on real people, too. In the story ‘Saved From Scrap’, in Edward the Blue Engine, a traction engine called Trevor is heading for the scrapyard before a kindly vicar steps in to save him. Could this be a case of the author writing a flattering version of himself into the series? Apparently not, since Awdry appears in later books as the Thin Clergyman, accompanied by the Fat Clergyman, who was based on his friend, the Rev Teddy Boston, a fellow railway enthusiast and owner of a traction engine called Fiery Elias.

Wednesday 5 October 2022

Oxfam, Kendal.

Female customer: Ooh look at that! Isn’t that cute? Kids’ books are always better, because they’ve got pictures in. Our books should have pictures in. Adult books should have pictures in.

Male customer: Hm.

[…]

Her: Have you seen that one that’s collectable? Footsteps in the

Snow or summat. You should look out for that. It’s valuable.

Male customer: Hm.

If you like visiting second-hand bookshops and you haven’t been to Astley Book Farm, well, what are you doing tomorrow?

On Monday 20 June 2022, I was in the car on the M1 again, this time accompanied by novelist, Small Pleasures podcast creator and (at that point, although not for much longer) Manchester Writing School colleague Livi Michael. Driving north, we slipped on to the M6, then came off at junction 3 21for Astley Book Farm, which is just a couple of miles north of the motorway, but, with its miles of bookshelves, thousands of books, and café boasting the largest fondant fancies I’ve ever eaten, a world away.

Livi had been recommending Ruth Rendell, so I picked up her Arena Novella, Heartstones, to join my small collection of Arena Novellas. I also found a duplicate copy of the Penguin edition of Derek Marlowe’s The Disappearance, one of my favourite novels of all time, and a lovely Penguin Modern Classics edition of Raymond Radiguet’s Devil in the Flesh. To replace my C-format edition of Stephanie Merritt’s Gaveston (Faber), I picked up a B-format mass-market edition from the same publisher. (In a bid to relieve congestion, I am replacing hardbacks with paperbacks, and C-format paperbacks with B-formats.) Livi kindly bought me a copy of Paris Tales (Oxford) edited by Helen Constantine.

We had coffee and fondant fancies then drove on to Lichfield, where, in the Oxfam Books & Music I found a lovely clean B-format edition of Tom Fletcher’s Witch Bottle (Jo Fletcher Books) to replace my C-format and Helen Hodgman’s Blue Skies & Jack and Jill (Virago Modern Classics) for its wonderful cover, Night and Day (1938), by the British Surrealist Roland Penrose. Livi was drawn to a copy of Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy in the crime section, which made me realise I should always check the crime shelves when looking for copies of The New York Trilogy. Luckily this copy was lacking any interesting elements, so I bought it for her, which might sound a bit odd until you’ve read the chapter in this book on The New York Trilogy, ‘Project For a Walk in New York’.

We then went a couple of doors down to the St Giles Hospice bookshop, where, because we didn’t have a bag between us, we 22showed the manager the books we’d bought in Oxfam and she teased us for having gone there first. I responded that we’d saved the best till last. Then, however, I didn’t find anything and was about to buy two CDs of Greig’s piano music, out of desperation, when I spotted a stack of Railway Series books, so I bought all seven.

At home, from my purchases I picked out Henry the Green Engine, illustrated by Dalby, and settled down with a brew. I nearly spat out my tea when I got to the penultimate page of the last story, ‘Henry’s Sneeze’. Henry is determined to punish some naughty boys who have been dropping stones from a bridge and have broken some of the windows in Henry’s coaches. His intention is to teach them a lesson by ‘sneezing’ when he next goes under the same bridge: ‘Smoke and steam and ashes spouted from his funnel. They went all over the bridge, and all over the boys who ran away black as n—.’

When complaints were made in 1972, twenty-one years after the volume’s original publication, Awdry at first stood his ground, arguing oversensitivity on the part of the race relations board, but later apologised and changed the description to ‘black as soot’. In my edition, a reprint from 1974, the N-word is still present. (In a second edition dating from 1952 that I saw in Oxfam Bookshop Wanstead, in October 2023, the N-word had been crossed out in ballpoint pen and the word ‘soot’ added.)

Luckily, there are more positive things to talk about in Henry the Green Engine. Such as the advertisements in the form of posters on the station wall in the penultimate illustration in the first story, ‘Coal’. Henry stands at the platform smiling in the direction of the Fat Controller while on the wall behind him we can see two posters. One reads: ‘You must read “THE THREE RAILWAY ENGINES”’ and the second one 23says, ‘READ ABOUT “JAMES THE RED ENGINE”’. Later in the same book, in the penultimate story, ‘Percy and the Trousers’, a double-decker bus going over a bridge has a banner advert on its side reading ‘TROUBLESOME ENGINES’. This was the second time the creators of the series had indulged in playful subliminal advertising. In the first story, ‘Thomas and the Guard’, in Tank Engine Thomas Again, Thomas is pulling coaches Annie and Clarabel out of a station, while in the foreground the station bookstall has a poster on its exterior wall reading, ‘NOW IN STOCK JAMES THE RED ENGINE’, and a newspaper headline board next to it headed ‘GRAND NEWS’ and, printed underneath, ‘ALL ABOUT THOMAS THE FAMOUS TANK ENGINE’.

This metatextual device, even while calling attention to itself as artifice and to the fictionality of the Sodor universe, has the unexpected effect of making the world of the story more believable. Look! They’re advertising the world of the books within the world of the books! It shouldn’t work and yet it does. Was this Awdry’s idea, or Dalby’s, or perhaps that of the editor, Eric Marriott? My money is on Dalby. Awdry had a bee in his bonnet about Dalby’s shortcomings, but Dalby’s mind was on the bigger picture. Awdry may have been the showrunner, as it were, with the island of Sodor forever expanding like a huge model railway inside his head, but Dalby was the art director or production designer, creatively inserting allusions here, visual quotations there.

It was Toby the Tram Engine that opened my eyes to Dalby’s ambition. In the final story in that book, ‘Mrs Kyndley’s Christmas’, the second illustration shows Mrs Kyndley sitting up in bed in a red dressing-gown waving to Toby, who is passing along the line immediately outside her bedroom window. On the 24