Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

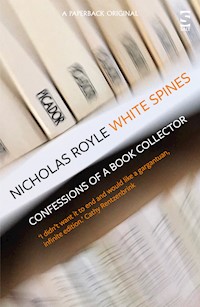

Editor's Choice, The Bookseller A mix of memoir and narrative non-fiction, White Spines is a book about Nicholas Royle's passion for Picador's fiction and non-fiction publishing from the 1970s to the end of the 1990s. It explores the bookshops and charity shops, the books themselves, and the way a unique collection grew and became a literary obsession. Above all a love song to books, writers and writing.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 362

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WHITE SPINES

Confessions of a Book Collector

NICHOLAS ROYLE

v

For my mum

vii

‘You want something physically in your hands, don’t you?

It’s the whole point of collecting.’ Customer in Church Street

Bookshop, Stoke Newington, London

Picadors are involved here and there (8).

Rufus, Guardian

‘That’s the point of second-hand bookshops. Being closed.’

Rob Gill, Gosford Books, Coventry

Contents

Introduction

On a weekday in the middle of March 2020, I get in the car in Manchester at 6.15am and drive in the direction of the Peak District. Up on the moors somewhere after Woodhead I see what look like three dark woollen jumpers flapping madly in the wind. Lapwings, it would seem, are like buses: you don’t see one for years and then three come along at once. The wild, joyful unpredictability of their aerobatic display is exhilarating. Lapwings, that is, not buses.

The roads are quiet and I enter the outskirts of Norwich at 10.30am. In the boot are two boxes of chapbooks. A chapbook is like a pamphlet. I’m getting one box-load signed in Norwich, the other in Ipswich, then back home for tea. Maybe around midnight. But not before, I hope, seeing my mum in Ipswich as well.

I find my way to Andrew Humphrey’s place close to the centre of Norwich; he and Ipswich-based Robert Stone are the latest two additions to my Nightjar Press roster of authors. Andy Humphrey signs his 200 chapbooks in good time (under an hour is good), which means I have time to make another call before heading down to Ipswich. I park the car on a meter and walk 2around the city centre. Most places are closed, but I did phone ahead to check that where I want to go is open. What I didn’t do, though, was save a picture of its location on a map and now I have no phone signal. Is Norwich one of those old city centres, like Canterbury and Chichester, full of cathedrals and other old buildings, but no phone masts? Eventually, almost by luck, I find myself on the right street and there it is, Oxfam Books & Music. This is where I go to commune, to rejoice, to give thanks and receive blessings. Part of me always wants to stop and take a moment before entering. But another part of me is too impatient and I feel myself being drawn in.

It’s a good branch. I can tell that as soon as I enter. The careful way things are laid out, the well-stocked ‘literature’ shelves, the general sense of order. I start looking in a few books. The prices are not cheap. I remember when that used to bother me about Oxfam Bookshop Chorlton in Manchester, them tending to charge £3 for a paperback instead of the more typical £2.50 at my local Didsbury branch, or 99 pence at Dalston Oxfam in Hackney, which is also local to me, some of the time. I rationalised it. Chorlton is well managed. This branch in Norwich is obviously well managed. I get the feeling they know what they’re doing. If they charge £4 for a paperback, they must know someone will happily pay it and that’s more money for Oxfam and its good causes.

I find, to my delight, a Picador I don’t think I have, Nomad by Mary Anne Fitzgerald, a 1994 edition of a 1992 non-fiction work subtitled One Woman’s Journey into the Heart of Africa. There’s no direct link between the content of this book and the emotion I feel in finding it – I rarely read non-fiction books and, if I’m honest, I’m unlikely to read this one – but the pleasure I feel as I take it from the shelf and look at the cover, which I am pretty 3sure I have never seen before, is real. The cover illustrations (front and back), which are credited to Mack Manning, employ mixed media – old photographs, handwriting, a photograph of the author, and postage stamps. I find there’s something irresistible about postage stamps on book covers.

Later, at home, I’ll look for other postage stamps on other Picador book covers and will not find as many as I thought I might. The signs are initially good as I start from the beginning of the alphabet – they are shelved alphabetically, by author – and soon come across a 1995 edition of Julian Barnes’s Letters From London 1990–1995 sporting not one, not two, not three, four, five or six postage stamps, but a lucky seven, all photographed, by Andrew Heaps, stuck to various appropriate artefacts: a Stan Laurel stamp on a bowler hat; a second-class stamp on a Labour rosette; a Charles and Diana stamp, torn in half, attached to a picture of the Queen. There’s a postage stamp from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic on the cover of Lesley Chamberlain’s Volga, Volga and a couple of pretend postage stamps on the covers of Tama Janowitz’s A Cannibal in Manhattan and Jill Tweedie’s Letters From a Fainthearted Feminist. I also find another cover by Mack Manning, although this one is credited to Mac Manning, on Gavin Bell’s In Search of Tusitala: Travels in the Pacific After Robert Louis Stevenson. Non-fiction books often seem to have rather long-winded titles, or rather they may have a short title designed to intrigue and a longer subtitle that has the job of describing, more prosaically, what the book is about. For instance, White Spines: Confessions of a Book Collector.

Also to my great pleasure – we’re back in Oxfam now, in Norwich, in the middle of March 2020 – on the ‘literature’ shelves, I find a 1973 Penguin edition of Quartet by Jean Rhys. Nine out of ten copies of Jean Rhys’s Quartet that you will 4find will be of a particular Penguin edition with a film tie-in cover and non-standard lettering on the spine. I owned a copy of this edition years ago and never read it and somehow the book and I parted company. Although I would like to have the novel, and the possibility of reading it, back in my life, I can’t have that non-standard spine messing up my Penguin shelves. I could shelve it elsewhere, with other non-standard A-format paperbacks, but with that spine, frankly, it wouldn’t look good anywhere. The 1973 edition, however, which I’m looking at now, is perfect. Author’s name in black, title in white, both out of orange. When Penguin still went for a uniform look on the spine, and cycled through a series of different designs, this was the one that I liked best – and still do – probably because when I bought or was given my first Penguins – Graham Greene’s A Sense of Reality and The Power and the Glory – in the mid 1970s, that was the spine, that was the template. Author name in black, title in white. (Cover illustrations, on the Greene titles, by Paul Hogarth.)

I am still browsing when I hear the shop manager – or volunteer – answer a phone call.

‘We’re only open for the next two days,’ he says, ‘because after Saturday we’re shut for four weeks – temporarily.’

I get home around midnight after a successful visit to Ipswich, where Robert Stone signed his box of chapbooks and I met my mum for a coffee, and then a long drive back along the A14, up the A1 and over the Peaks, where I stopped, briefly, to listen to the weirdly metallic cries of lapwings in the darkness. To writer and musician Virginia Astley, creator of the 1983 album From Gardens Where We Feel Secure, the cry of the lapwing sounds like an oscillator on an early analogue synthesizer, the VCS3.

On my Picador shelves at home I find I’ve already got Nomad 5by Mary Anne Fitzgerald, so I was wrong about not having seen Mack Manning’s cover before, but it doesn’t matter. The duplicate copy can join what I have started calling my ‘shadow collection’, the purpose of which is so far unclear to me. The Penguin edition of Quartet can join my other Jean Rhys titles on the Penguin shelves. Months later I will post a picture of my modest Jean Rhys collection on Instagram and someone will comment that she is their favourite writer. Someone else will say, ‘These are brilliant.’ Another commenter will post a black heart emoji and another will say she has an edition of After Leaving Mr Mackenzie with a photographic cover, which I will immediately think I need to look out for, to go with my Faith Jaques-illustrated edition. An old friend will post, ‘Get some bloody writing done. #displacementactivity’.

I am, by then, getting some bloody writing done, because I have a deadline, and deadlines help, especially the sound of them whooshing by, as Douglas Adams once said. But, really, I’ve been writing this book since I was nineteen or twenty, using ‘writing’ in the very loosest sense. Researching, perhaps.

Christmas, 1980. My parents gave me a single. I’ve no doubt they gave me some other presents as well, but ‘Dark Entries’ by Bauhaus is the one thing I know they must have given me that Christmas, because it was released in 1980 and I definitely remember being given it one Christmas and I wouldn’t have wanted to wait more than a year before owning it. I had heard it on John Peel; he played it several times during 1980, as well as a session from the band that I still have on home-recorded audio cassette. The ‘Dark Entries’ picture sleeve featured a detail from a painting credited on the back as Venus Asleep by Paul Delvaux. Having never previously heard of Delvaux, I became 6at that moment an instant, lifelong fan. A pale-complexioned, wide-eyed woman occupies the centre of the image. She wears an elaborate hat of scarlet feathers, her upper body covered by a tight black garment that gives her torso the appearance of a dressmaker’s dummy – with arms. Her right arm is down, extended a short way from her body, her left arm bent at the elbow, so that her left hand is raised, palm open in an ambiguous gesture as she approaches an upright skeleton, which, like the backdrop of classical structures, is bathed in moonlight. In the background, a tiny female nude embraces a thick white column. There was about this image a mood, an atmosphere of sinister melancholy that appealed to me immediately and profoundly. It was a coup de foudre, although I may not have known the term at the time and probably would have said, if you had asked me, that it was love at first sight.

My second date with Delvaux took place within months. Having written a fan letter to Peter Murphy, singer and lyricist with Bauhaus, at the Northampton address on the back of the ‘Dark Entries’ sleeve, I was thrilled to receive a reply, on stiff yellow card that he had folded and squeezed into my stamped addressed envelope. He told me that Venus Asleep was owned by the Tate Gallery, as it was then called, in London. I duly made the trip to the capital, unaware that only a fraction of a major gallery’s holdings will be hanging at any time, but I was lucky. I was excited to see that the detail reproduced on the sleeve of the single accounted for less than a third of the painting, which featured the sleeping Venus of the title in the foreground and four other female nudes in addition to the small figure in the background. The moonlight washing across the bones of the skeleton, the columns and steps of the classical buildings and the bodies of the female figures was provided by a mere crescent, 7which could not possibly, on an actual night in the real world, have cast so much light.

In September 1982, aged 19, I moved to London to study French and German at Queen Mary College, University of London. The college was in the East End, but I moved into an intercollegiate hall of residence on Cartwright Gardens, between Euston and St Pancras, just south of Euston Road. If you came out of Hughes Parry Hall and walked south, away from Euston Road, within less than a minute you were on Marchmont Street, passing Gay’s the Word bookshop on the left and, on the right, if it was there then, which it wouldn’t have been, because he was still alive, a blue plaque recording the fact that Kenneth Williams had lived in a flat above his father’s barber shop at No.57. I know Kenneth Williams was still alive because some time that year or the year after or, in any case, certainly before 1988, I walked past him on Tottenham Court Road, just a few minutes’ walk west of Marchmont Street. Russell T Davies has said that Williams rarely strayed far from the area around King’s Cross and that he never ventured further west than the Edgware Road.

I was walking north, on the right-hand side of Tottenham Court Road, having just crossed Great Russell Street, and there was Kenneth Williams walking towards me, a slight figure in a dark raincoat, of similar height to me. I recognised him at once and smiled, and he smiled back. I had never been a fan of the Carry On films, but I had loved Williams’s contributions to Round the Horne, which we would listen to at home, whether repeats on the radio or on my dad’s reel-to-reel tape recorder, alternating with The Goon Show.

But, to return to Marchmont Street, go back ten paces to Great Russell Street, turn left, walk past the site of the old 8Cinema Bookshop at Nos. 13–14 on the right, and, on the left, offices upstairs at No. 102 where I worked at the International Visual Communications Association (IVCA) between October 1987 and November 1988. Some readers might remember the Cinema Bookshop, a tiny space crammed from floor to ceiling with books on the movies; given my lifelong love of film and the fact that I worked just across the road for a year, it doesn’t make a lot of sense that I only went in there a handful of times, unless it was simply that I was more often drawn, as I had been when I was a student, to Skoob Books.

The first time I went looking for Skoob Books, which in the autumn of 1982 was located on Sicilian Avenue, a pedestrian cut-through from Vernon Place to Southampton Row, it took some finding. It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that Sicilian Avenue made it into the A–Z. In Skoob, they shelved all their Penguins together; I had seen that done elsewhere, all those orange spines. In addition, beyond the Penguins, in the next room, there was a wall of white spines. These, I saw on closer inspection, were Picadors, and I had never seen Picadors shelved together like this. (Why, I vaguely remember thinking, would you do that?) I’m not even sure I had seen any Picadors at all before. Maybe I had, in Paramount Books on Shude Hill in Manchester, or on Dick’s market stall, Ipswich, where my family had moved in the summer of 1982, but if I had, they had not made much impression. It was when I found, among these tall, white-spined paperbacks in Skoob Books, a novel called Ice by Anna Kavan, that I knew there was something special about Picador.

The cover of the Picador edition of Ice features a painting of a female nude. The time of day is night, the setting a puzzling combination of interior and exterior. The female figure stands face on to the viewer, eyes closed, a lacy white gown draped 9over her right arm while in her right hand she holds a burning candle. To one side of her is a cobbled street, to the other a red carpet leading to a set of stairs and a closed door. If it weren’t signed in the bottom-right corner – P. DELVAUX – you would still know the identity of the artist, if you had seen his Venus Asleep. This painting, Chrysis, dates from 1967, the same year Ice was first published by Peter Owen – a nice touch and, I would guess, not a coincidence.

I have bought numerous copies of the Picador edition of Ice. I have given several to friends as presents, most of those, once it became a sort of joke, to my good friend Adele Fielding, and I have had to replace copies loaned and never recovered. (I drop a quick line to Dell to ask her if I should include the grave accent on the middle ‘e’ in Adele. She responds: ‘I don’t mind what you call me, but my actual name as given by my parents is Adele Fielding – my parents were only aware of an accent as being something that you needed to get rid of to get on in life.’ Anyone who knows Dell knows how fabulously she has got on in life, and her Rochdale accent is as broad now as it was the day she left Syke, for London, in 1982.) The edition has become scarce, for which perhaps I should take some blame. At the time of writing, there are only three copies available on AbeBooks. There are newer editions with forewords and afterwords by notable writers, but for me the Picador edition (complete with Delvaux cover and introduction by Brian Aldiss) is unbeatable. It was one of sixteen titles published by Picador in 1973.

The list was launched the previous year, in October 1972, by Sonny Mehta, as an imprint of Pan Books, with the aim of publishing outstanding international writing in paperback. They launched with eight titles: A Personal Anthology by Jorge Luis 10Borges, Trout Fishing in America by Richard Brautigan, Heroes and Villains by Angela Carter, Rosshalde by Hermann Hesse, The Naked i edited by Frederick R Karl and Leo Hamalian, The Bodyguard by Adrian Mitchell, The Lorry by Peter Wahloo and The Guérillères by Monique Wittig.

I have copies of all of these. I have copies of the sixteen titles published the following year. I also have— Actually, I don’t have copies of the nineteen titles published in 1974. I only have eighteen of them. But I’m getting ahead of myself. This is supposed to be an introduction.

One of the striking things about the eight books, looking at them today, is how slim they are, how unbloated they appear. No literary agent or commercially driven editor told these authors that a novel has to be 90,000 words. Six of these books are around 150 pages; The Lorry is 250 pages and The Naked i just over 300. When an Instagrammer posts a picture of the seventeen books she has read in January, or February, they all look like new releases and they all have great big fat spines, with the odd exception by Max Porter. It’s great that people are reading new books; I just wish they weren’t all so long. Before I was commissioned to write this book for Salt, I worked for them as a commissioning editor, acquiring approximately twenty-five books over nine years with an average length of just under 50,000 words.

Also striking are the covers of the eight Picador launch titles. Three utilised existing paintings, by Dalí, Grünewald and Hundertwasser. The Brautigan cover was based on the first US edition. Mitchell’s The Bodyguard used an original photograph by Roger Phillips and The Naked i employs graphic design, credited to Paul May, inspired by, but an improvement on, the first US edition. Rosshalde was the first in a series of six books by 11Hesse to appear in Picador with cover illustrations by Guernsey artist Peter Le Vasseur, who was to do at least one other cover for the imprint in a similar style, for John Livingston Lowes’ The Road to Xanadu: A Study in the Ways of the Imagination.

The cover for Wittig’s The Guérillères was by the English surrealist painter and prolific book and album cover artist John Holmes, who, discovered and nurtured by art director David Larkin at Granada Publishing (who would go on to be part of the team that set up Picador at Pan), had already done notable covers for Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch and Nabokov’s Despair for Paladin and Panther, respectively, and would go on to do covers for Picador editions of Beckett and Pynchon as well as Jung’s Man and His Symbols and dozens if not hundreds of covers for other publishers.

If my relationship with Picador started with Ice, it underwent a change at Christmas 1983, when my parents gave me a copy of Black Water: The Anthology of Fantastic Literature – that title/subtitle formula again, but, unusually, on a book of fiction – edited by Alberto Manguel. At a little under a thousand pages, this landmark Picador anthology, published that same year, contained a small number of stories I had already read several times, such as Franz Kafka’s ‘In the Penal Colony’, EM Forster’s ‘The Story of a Panic’ and Horacio Quiroga’s ‘The Feather Pillow’; numerous stories I hadn’t read before by authors I liked very much, including Saki, Daphne Du Maurier, Graham Greene, Jorge Luis Borges and Marcel Aymé; and dozens of stories by writers I had never read, but who I would read, in this book and in other books, over the years to come.

I don’t know if I asked for Black Water for Christmas or if my parents just knew.

I now own two copies of Black Water. On a Sunday in April 122017, I visited a branch of Oxfam, where I found, in the short stories section (I like it when a second-hand bookshop has a short stories section), two books side by side. One was Black Water, the same Picador edition I already had, and the other was Stepping Out, Short Stories on Friendship Between Women (Pandora), edited by Ann Oostuizen. I noticed a dedication in Black Water: ‘Dear ______, fondest love, _____, 25.12.83’. I thought, I know someone called ______, and I happened to know that she knew or had known a woman called _______. And then, in the copy of Stepping Out, I saw, on the flyleaf, in blue ballpoint, ‘________ _______’. The copy of Black Water had obviously been ______’s as well, inscribed to her by _______ ______. How wonderfully ironic that this gift from ______’s friend _______ had now been given away along with a book of stories about friendship between women. I decided not to buy the books and left, realising about half an hour later that I had to buy them, after all, and went back and did so.

If I ever decide I don’t need two copies of Black Water, I know someone who would happily accept the inscribed copy. WB Gooderham is the author of Dedicated to … The Forgotten Friendships, Hidden Stories and Lost Loves Found in Second-hand Books (Bantam Press), which grew out of Wayne Gooderham’s website of the same name, which grew out of his collection of second-hand books containing dedications, the more personal the better. On top of Wayne’s wardrobe in the north London flat he calls the Bunker are boxes and boxes full of books that he has ‘absolutely no interest in reading’ but that he has been collecting for many years for the dedications written within them. I think of Wayne as a fellow traveller, although as I write these words in February 2021 no one is doing a lot of travelling; maybe virtual cell mate would be more appropriate. The point 13is that I probably have as many books as Wayne does that I have absolutely no interest in reading.

I also have, as I’m sure Wayne does, hundreds of books that I have read, and hundreds of books that I want to read, and hundreds, well dozens, of books that I have read and want to reread, as well as a certain number of books that I do regularly reread. Another friend (I say, ‘another’, which presumes I can call Wayne a friend), a very old friend, the writer Conrad Williams, has a dislike, if not a deep, pathological loathing, for that word – ‘reread’. I know what he means. At least, I think I do. You know the sort of thing. ‘I’m rereading Proust.’ ‘I was rereading Hamlet the other day.’ ‘This summer, when we go to Tuscany, I am looking forward to rereading Nabokov’s stories.’ That sort of thing. They want you to know they’ve read Proust or Hamlet or Nabokov’s stories before. In fact, they’re terrified lest you think they’re so ignorant and poorly read that they’re only just getting around to reading Proust or Hamlet or Nabokov’s stories.

When I say ‘the writer Conrad Williams’, I mean the author of London Revenant, The Unblemished and One Who Was With Me, among many other novels and short story collections, rather than the literary agent with Blake Friedmann who is also a novelist (Sex and Genius, The Concert Pianist). The subject of writers sharing a name with another writer is a subject I will return to.

For now, as my deadline approaches faster than the speed at which I can write, I’m engaged in reading, or in some cases rereading, those first eight Picador launch titles. A couple of days ago I finished Angela Carter’s Heroes and Villains, but I won’t comment on that yet as I don’t want to start off on a negative note, especially not in relation to such a well-loved figure. Even 14I, a poor strategist, can see that that would be rather foolish. I’m currently reading Richard Brautigan’s Trout Fishing in America, which I thought I might have read before, but it’s not at all familiar and you’d think it would be, what with all the fun he has with different interpretations of who or what is meant by Trout Fishing in America. I’ve barely finished reading Trout Fishing and moved on to Monique Wittig’s The Guérillères when, in my current lockdown Scandi noir, 2017 Norwegian crime drama series Monster, police chief Ed Arvola, played by Bjorn Sundquist, is sitting at home reading Trout Fishing in America. His wife asks him what it’s about and he says, ‘Definitely not about trout fishing. Just lots of weird stories.’ This is not an unfair assessment, although there’s more about trout fishing than I expected. The best story, or chapter, comes towards the end. The Cleveland Wrecking Yard is selling a trout stream, but selling it in foot-long lengths that are stacked up outside the back of the shop. ‘“We’re selling the waterfalls separately of course,”’ says the man, ‘“and the trees and birds, flowers, grass and ferns we’re also selling extra. The insects we’re giving away free with a minimum purchase of ten feet of stream.”’

Having owned a copy of The Naked i since the mid 1980s and dipped into it many times, it’s only recently that I’ve read it from start to finish. It’s quite a thing to read Kafka, Borges, Cortázar and Ellison one after another. I hadn’t read Richard Wright’s ‘The Man Who Went to Chicago’ or Carlos Fuentes’ ‘Aura’ before and both are among the highlights. Rereading Ted Hughes’s ‘Snow’ reminded me that I once applied to Manchester’s Cornerhouse for a little pot of funding to edit a mini-anthology called Snow of stories called ‘Snow’, which would have included reprints of stories by James Lasdun, Jayne Anne Phillips and Miles Tripp alongside the Hughes and an 15original story by one of my students. The application was unsuccessful. My favourite story in The Naked i is Sylvia Plath’s ‘Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams’, which begins, ‘Every day from nine to five I sit at my desk facing the door of the office and type up other people’s dreams.’ An administrator in a hospital, Plath’s narrator also takes her work home, where it consumes her. I once put together a book called The Tiger Garden: A Book of Writers’ Dreams. Every day I sat at my desk typing up other people’s dreams. Because it was a charity project intended to benefit Amnesty International, I was unable to offer payment to contributors. ‘I don’t dream,’ wrote actor and writer Dirk Bogarde in response to my request, ‘and not for “free” anyway.’ The book was dismissed by critic Harry Ritchie as ‘uniquely pointless and stupid’, so he’s not going to enjoy the current book, which will feature some of my dreams about books, writers, bookshops and critics, including at least one in which Harry Ritchie appears. Since it’s widely believed that there’s nothing more boring than other people’s dreams, I’ll try not to include too many and will use them as section breaks, which could be easily skipped, or studied, or simply enjoyed, according to your preference. They’ll look like this, with a date.

Saturday 29 October 2016

I found two white-spined Picadors in a second-hand bookshop. I can only remember – or perhaps I only properly saw – one of them, a non-fiction book about the Tarot.

Not to be confused with snatches of overheard conversations, which will also be dated and will include a location and brief note on who is speaking, and be laid out like this.16

Friday 31 January 2020

Thai Café, Stoke Newington, London.

Couple, late 50s, eating dinner.

Her: It’s interesting.

Him: That’s not much to say about a novel. All novels are interesting.

As far as I know, there haven’t been any Picador non-fiction books about the Tarot. There was Calvino’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies, but that’s fiction.

Having recently read Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, I’m not sure I’d agree that all novels are interesting.

Susanna Moore’s In the Cut, a brilliant erotic thriller that would be one of my top ten Picadors, endears itself to me on only the second page: ‘Some of them admitted that before completing the Virginia Woolf assignment they’d smoked a little dope and it had helped.’ I don’t, but I can imagine it might.

There will be chapters in which the main focus will be on various things, like: covers; inclusions – my preferred term, possibly even my coinage, for ephemera found in second-hand books; other people’s books; names and inscriptions; Picador Classics; second-hand bookshops; French books and bookshops; writers with the same name as other writers; memories of Picador authors. Throughout, I will be hoping to throw some light on to what makes Picador so special that I decided to collect every single B-format Picador paperback published between 1972 and 2000, when the publisher abandoned its commitment to the white spine with black lettering in a more or less uniform style (which has started to sound to me like a fairly long-winded yet niche specialist subject on Mastermind). What it will not be is a history or biography of Picador; nor will it be a systematic guide 17to second-hand bookshops like a Skoob Directory or Drif’s Guide. I’ll try to stick to the point while at the same time allowing digressions. Adelle Stripe, responding to my series of lookalike photographs on social media, called me the ‘Cindy Sherman of Northern Literature’, which I liked, but I hear myself going on a bit in this introduction, which has topped 5,000 words, and I wonder if I might not be the Ronnie Corbett of Contemporary Letters, and I mean principally for his armchair monologues rather than the fact his feet didn’t quite reach the floor. And, if that’s the case, who is my Ronnie Barker?

I might be indiscreet, but I’ll try not to offend. I may occasionally go into slightly bewildering detail, but I’ll try not to be boring. Someone suggested to me that this book might be like ‘that Nick Hornby book, but about books instead of records’. If it is, it will be by accident, because I haven’t read it, although I have read Giles Smith’s excellent Picador memoir Lost in Music, which came out in the same year as High Fidelity, which, it now occurs to me, was a novel anyway. In November 2020 I read Chris Paling’s Reading Allowed: True Stories & Curious Incidents From a Provincial Library (Constable), which I found in the excellent Bopcap Books in Levenshulme Antiques Market, which was briefly open between one lockdown and the next. Novelist Paling’s highly readable and likeable memoir of his career-switch from BBC radio producer to public librarian does a number of the things I had been hoping to do in White Spines, which was mildly concerning but also perhaps reassuring. If Chris Paling can do this, so can I, sort of thing.18

1

Cover versions

Thursday 5 March 2009

I’m with Graham Joyce and another, unidentified member of the England Writers team, and David Beckham. I shake hands with Beckham. His hand is curiously light and bony. Graham and the other writer, both in football kit, stand either side of me, dwarfing me, and we have a bit of a laugh about it. I ask if it is a good idea to draw attention to the short stature of the goalkeeper, since it seems I am to be the goalkeeper for this match, not Graham.

Everyone I meet in Leicester – on Monday 8 May 2017 – says, ‘It’s not as warm as yesterday.’ I can believe it; it only warms up when I am walking briskly between bookshops. The meeting I’m in town for, at De Montfort University, is on the Tuesday morning, early enough that they’re putting me up in a hotel on the Monday night. A little online research suggests I will be able to fill an afternoon easily enough before paying a visit to the family of my late friend, the writer Graham Joyce.

I start at Maynard & Bradley on Silver Street in the city centre. It’s a charming shop with an affable owner, but I come 20away empty handed. I survey a smattering of charity shops with the same result. Tin Drum Books on Narborough Road looks more promising. It’s the classic second-hand bookshop: tall bookcases, full shelves; pleasing level of order despite tattiness and frayed edges; older gentleman sitting behind the counter quietly getting on with whatever the proprietors of second-hand bookshop get on with. I inspect the shelves, checking non-fiction first, saving up fiction like the icing on a cake. I don’t find anything in non-fiction, so I move on to fiction. I start at the end of the alphabet and pick out Man Descending by Guy Vanderhaeghe. He sounds Belgian but is Canadian; the fact his book is a short story collection published in the 1980s by Sceptre is good enough for me. It’s not all about the Picadors. My heart beats a little bit faster when I spot the tattered spine of William Trevor’s The Children of Dynmouth. I have a copy in Penguin, but this is a King Penguin, so the chances are it could have a James Marsh cover. I tease it out and see the eyes floating in the sky, the lighthouse nose and the bird for a mouth. The book is in poor condition, but I love these covers. I love them like I love those by Grizelda Holderness for Emma Tennant in Picador and Tom Adams’ covers for Fontana’s Agatha Christie series. I assemble a smallish pile of books (Charles Nicholl’s The Fruit Palace and Justin Cartwright’s Look at it This Way in Picador, Louis Aragon’s Paris Peasant, which I already have in Picador but this is a Picador Classics, so, since I also collect the black spines of Picador Classics, I have to have it, and Anita Desai’s Games at Twilight in King Penguin) that come to £11.50. I head to the counter, wishing I felt able to say to the man that £2 seems a bit steep for the William Trevor, given that it is literally falling apart. He counts them up and says, ‘Let’s call it £10, a nice round number.’ 21

The next shop on my list is Treasure Trove on Mayfield Road. As I walk I look at the books I have just bought. The Anita Desai short story collection has a cover by Poul Webb, who illustrated a whole series of Anita Desai covers for King Penguin in the 1980s: vividly coloured landscapes and gardens, some with figures, some without, but most featuring a bird in flight. The bird may not be the first thing you see, but once you’ve seen it, you can’t unsee it. The James Marsh cover on the Trevor novel also features a bird, which is typical of Marsh, across his many book and album covers, but not of this particular series of books for Penguin, which are all representations of human faces made out of unusual features, including a letter box for a mouth and irises made out of jet engines. The Dynmouth cover reminds me of Marsh’s cover for a Picador book, Randolph Stow’s 1979 novel Visitants, with its suggestion of a face using two flying saucers and an arum lily. (In February 2021, as I write this chapter, I’m charging through Monique Wittig’s The Guérillères, translated from the French by David Le Vay, and, on page 52, I read, ‘It is during this movement that they exhale a perfume of arum lily verbena which spreads instantly through the surrounding space.’) As an enthusiast, rather than an art historian, I’m not very good at categorising art, but artist and designer John Coulthart describes Marsh’s style as ‘hard-edged, post-Surrealist’.

Most notable about the Picador Classics edition of Aragon’s Paris Peasant is not the cover, if illustrator Max Ellis will forgive me, but the biographical note about the author, which begins and proceeds in the conventional manner – it’s factual, neutral and dry, precisely how a biographical note should be – covering his being a founder of the Surrealist movement before converting to communism, then distinguishing himself as a soldier in WWII 22and in the Resistance. Then, we read, ‘His post-war fiction was crudely propagandist and he became little more than a poseur with dyed red hair in the years before his death in 1982.’

I find out later I could have reached Mayfield Road by going up New Walk, the most beautiful street in Leicester. On London Road, I pass the Church of St James the Greater, where in 2014 I attended Graham Joyce’s memorial service. It’s a cliché, of course, but Graham was one of those larger-than-life, passionate, funny and generous characters you simply can’t quite accept are no longer around once they’ve gone. Dying far too young at 59, he was as committed to defending the goal-mouth for the England Writers football team as he was to defending disadvantaged groups generally.

The Mayfield Road address for Treasure Trove turns out to be a private residence. What can you do except take a step back and stare up at a building resentfully? Maybe you assess how recently the change of use took place? Can you still smell books in the air? In this case, 21 Mayfield Road doesn’t look as if it has ever been a second-hand bookshop. You start to doubt the reliability of Google. You wonder if Donald Trump is to blame. Or the Russians. Better for the blood pressure just to walk on, in this case south into increasingly leafy neighbourhoods, eventually stumbling upon the charming villagey centre of Clarendon Park, with its twin bookshops either side of Queen’s Road run by Age UK and LOROS (a local hospice charity). In the former, where ladies of a certain age gather for lattes at the tables in the window, I find an Edmund White collection in Picador that I have never seen before, Skinned Alive. You see some White titles a lot – A Boy’s Own Story, The Beautiful Room is Empty, even Nocturnes For the King of Naples and Caracole – but Skinned Alive is a new one on me. Also: a King Penguin edition of JM 23Coetzee’s Waiting For the Barbarians, with, tucked in between pages 98 and 99, a newspaper clipping of a letter from Coetzee to the Times Higher Education Supplement dated 7 October 1988 in which he, as a professor at the University of Cape Town, writes in support of the cultural and academic boycott of South Africa.

I remember the clip on YouTube in which Coetzee introduces British writer Geoff Dyer to a festival crowd at Adelaide Writers’ Week in March 2010. Dyer gets up and goes to the microphone. ‘Thank you, John, and thank you, everyone,’ says Dyer. ‘What an honour. If someone had told me twenty years ago that I’d be here in Australia and I’d be introduced by a Booker Prize-winning, South African, Nobel Prize-winning novelist, I don’t know what I’d have said. I mean, yeah, what would I have said? I would probably have said, “Well, that’s incredible, because Nadine Gordimer is my favourite writer.”’ Dyer’s face breaks into a smile, the audience fall about laughing and Geoff glances across at the Booker Prize-winning, South African, Nobel-Prize-winning novelist to see if he appreciates the joke. On Coetzee’s granite face there is not a flicker.

Over the road in LOROS I buy a copy of Graham Joyce’s thirteenth and penultimate novel Some Kind of Fairy Tale. I ask the shopkeeper if he knew Graham. He didn’t, but when in conversation I mention that Graham had been a fan of Coventry City, the man opens up. He’s a Derby fan himself. He doesn’t watch Match of the Day, he says, because he can’t bear it when men talk about football. Neither of us comments on the irony as we proceed to have a friendly and apparently mutually enjoyable chat – about football.

I have a sense that Clarendon Books, around the corner on Clarendon Park Road, could be the highlight of my afternoon and, indeed, when I get there the signs are good. In one of the 24boxes outside is a copy, albeit in poor condition, of Christopher Kenworthy’s short story collection Will You Hold Me? I’ve known Chris as long as I knew Graham, since the late 1980s. He has lived in Australia for many years now. His collection contains some of my favourite short stories. They are as affecting as they are odd. ‘Odd’, in my opinion, or in this context anyway, is an entirely positive descriptor.

As I push open the door of Clarendon Books, the carpet beneath it rucks up. I poke my head around a pile of books and apologise to the proprietor. ‘It’s been happening all day,’ he tells me. Clarendon Books is similar to Tin Drum Books, although with more books crammed into less space. I find a Picador by John Cowper Powys that I don’t have – Weymouth Sands. When I get it home it will join five others of his books and the six of them will account for an impressive nine inches of shelf space. Cowper Powys, a writer of unusually long books, died the year I was born, our lives overlapping for only three months. It says on the back of Weymouth Sands