6,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: DSP Publications

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Since the loss of his lively, charming wife to cancer six years ago, minister Paul Tobit has been operating on autopilot, performing his religious duties by rote. Everything changes the day he enters the church lobby and encounters a radiant, luminous being lit from behind, breathtakingly beautiful and glowing with life. An angel. For a moment Paul is so moved by his vision that he is tempted to fall on his knees and pray. Even after he regains his focus and realizes he simply met a flesh-and-blood young man, Paul cannot shake his sense of awe and wonder. He feels an instant and overwhelming attraction for the young man, which puzzles him even as it fills his thoughts and fires his feelings. Paul has no doubt that God has spoken to him through this vision, and Paul must determine what God is calling him to do. Thus begins a journey that will inspire Paul's ministry but put him at odds with his church as he is forced to examine his deeply held beliefs and assumptions about himself, his community, and the nature of love.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 321

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Published by

DSP PUBLICATIONS

5032 Capital Circle SW, Suite 2, PMB# 279, Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886 USA

http://www.dsppublications.com/

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of author imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

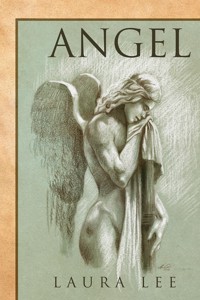

Angel

© 2015 Laura Lee.

Cover Art

© 2011 Anne Cain.

Cover Design

© 2011 Mara McKennen.

Cover content is for illustrative purposes only and any person depicted on the cover is a model.

All rights reserved. This book is licensed to the original purchaser only. Duplication or distribution via any means is illegal and a violation of international copyright law, subject to criminal prosecution and upon conviction, fines, and/or imprisonment. Any eBook format cannot be legally loaned or given to others. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law. To request permission and all other inquiries, contact DSP Publications, 5032 Capital Circle SW, Suite 2, PMB# 279, Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886, USA, or http://www.dsppublications.com/.

ISBN: 978-1-63476-173-4

Digital ISBN: 978-1-63476-174-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015904659

Second Edition November 2015

First Edition published by Itineris Press, 2011.

Printed in the United States of America

This paper meets the requirements of

ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For my father.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

DEEPESTGRATITUDE to Jennifer Hunter, who was not only Angel’s first reader but the most constant supporter of this project. Thank you to Crystal Brunell, Jodi Connors, Lisa Crawford, Carol Lee, Jennifer Lee, and Laura Ross for their generous feedback.

Thank you to my thoughtful editor, Lynn West, whose keen eye for detail helped shape Angel, and to cover artist Anne Cain, who gave the concept of an angel a beautiful shape.

THE MOUNTAIN

“From the muses of Helicon, let us begin our singing, that haunt Helicon’s great and holy mountain, and dance on their soft feet round the violet-dark spring….”

—Hesiod, “Theogony”

THEMOUNTAIN is nothing but itself. It does not speak. It has no message, and yet it is the great metaphor maker. It reflects what the traveler brings to it: a getaway, quiet majesty, a challenge, security, or danger. It is all these things or none of them, and the traveler sees whichever he looks for in it. For millennia people have come to high mountains and sat at their feet or scaled their peaks, hoping to return with the answer to a question.

Six days a week, from Tuesday through Sunday, Paul Tobit drove a sightseeing bus on the winding roads at the base of Mount Rainier in Washington. People often asked him if he got tired of the view. He never did. The mountain was vast enough to provide endless material for wonder and contemplation. There was the sheer majesty of the towering peak, the way it changed with the seasons and the weather, the sense of danger and foreboding that came with its snow cap, where the oxygen was thin and adventurers risked life and limb for the chance to say they reached the summit.

“Magnificent in its symbiosis.” Those were the words Paul usually used on his tours to describe Rainier. Up on the mountain, everything is interconnected. The logs fall and they turn into mulch, which becomes soil for new trees. There’s an algae up there that grows in a wispy hanging vine. It somehow draws from the tree without choking it. To Paul, it was evidence of the hand of God.

The philosopher Edmund Burke described two different responses to natural beauty in his treatise On the Sublime and Beautiful: one originates in love, the other in fear. Fields full of flowers, meadows and ponds covered in lilies are comforting; they give people a sense of harmony and security. They are pretty, but they are not sublime. To be sublime, a landscape has to evoke not only beauty but terror—a sense of something so great, so enormous, with a life span so long that we can scarcely comprehend it. It renders us weak and insignificant in comparison.

Mount Rainier is sublime. Even the most arrogant man would have to be humbled in its presence. It reminds us that the world is much bigger than we are, that there are still places that we cannot blast, or sell, or pave, or control. Is it any wonder that Jesus, who “went up to the mountain to pray,” came down with the message that “the meek shall inherit the earth” and delivered the sermon “on the mount”?

Paul enjoyed his job. There was no gossip, no politics, no deadlines or performance reviews. He found both solitude and company on the side of the mountain. The tourists who filed onto his bus each day were always in a good mood—you don’t take a sightseeing tour to be miserable and grumpy. The groups bonded quickly over their shared temporary interest in snapping photos of nature. After a pleasant day together, they parted ways without any messy breakups or accusations.

People take vacation snaps in a futile attempt to capture the mountain and the moment so they can take them home to flat states like Indiana and Kansas. There is something in our DNA that makes us want to hold onto the transitory. Photographs give us the pleasing illusion that we can. Yet the image never quite evokes the experience…. “The picture doesn’t do it justice. You had to be there.”

People also take photographs so they will not feel lonely. They take them for the absent friends they wish were there to share the view. There are few things more melancholy than looking out on a truly sublime landscape and realizing you are experiencing it all alone. This was something Paul knew quite well.

The ritual of being a tour guide appealed to him. What was for the tourists a singular experience was for Paul a repeating experience. Each day he would unlock the bus, jot notes in a couple of logs, and fill the gas tank. At 10:00 a.m., the visitors started to file in with their passes and take their seats. Some privacy-loving folks went straight for the back. The ones who liked to ask questions sat near the front. In the middle were the social ones who hoped to meet their new neighbors during the ride.

Paul rounded a familiar curve in the road and heard the expected sighs and murmurs as the tourists saw a spectacular view for the first time. He had developed an act of sorts over the course of two years. He knew what guests always asked, and he told them before they had the chance. He knew what jokes and lines made people laugh. He had his share of inspirational and thought-provoking observations too. And if that wasn’t the group’s mood, he could ply them with trivia and hold a contest, awarding a T-shirt to the winner. At the end of the day, his pocket was always stuffed with more than his share of tips. He would never become rich on his mountain proceeds, of course, but he had everything he needed—regular meals, a small cabin with a spectacular view, and time to gaze at the mountain and reflect on life.

Throughout his tours, Paul liked to make references to burning out on his old job. Inevitably, toward the end of the tour, someone would ask what his old job had been. He loved their reactions when he said, “A minister.”

“SPECIAL FRIEND”

“I summited Mount Rainier.” Words are inadequate to the experience—all the preparation, every single step, the times you think you can’t go on, the cold, the thin air—all that it means to accomplish that feat—it’s lost to everyone but the individual who undertakes the journey.

OFALL the parts of his job as a minister, Paul liked funerals the most. Of course, “like” wasn’t the right word. No one “liked” having to perform a funeral. Yet ever since his wife, Sara, died, Paul found funerals, and only funerals, truly satisfying. Though he was an introvert by nature, he had always been a compassionate and thoughtful minister. Even as a young man just starting out in his ministry, he intuitively grasped when to offer comforting words and when to allow a silence. He had a stock of memorial prayers that made people cry and smile with private memories in the right balance. You could say he had developed the craft and had a good funeral technique.

After Sara died, however, Paul felt the full weight of performing funerals. He became part of a fraternity of grief and understood all the emotions of the person in front of him. He remembered the small gestures: the offers of food, the shared memories, the shoulders he cried on. He came to believe he could give sermons for the rest of his life and it would never have as much meaning as holding a recent widow’s hand and letting her cry for as long as she needed. It was the one time he still felt blessed to be a minister, to have the opportunity to know he was making a difference.

Until she got sick, Sara had been full of life and energy. It seemed like only yesterday that they had met. She sat behind the reception desk in the church office. He was smitten immediately by her charming freckles, her mane of curly red hair, and her warm and genuine smile. She made it her life’s mission to help him take his life less seriously. He never fully understood how someone so personable, outgoing, and universally loved could have chosen him. His joy existed in her. When he buried her in the cemetery beside the church, he buried his joy with her.

Could it really have been six years since Sara died? Sometimes it seemed like an eternity, and sometimes it seemed like only a day. At first he had believed it had to be a mistake. Someone like Sara could not possibly stop existing. She would walk through the door in her favorite pastel dress and laugh the way she always had. It was months before that feeling stopped haunting him.

The constant invasive memories of Sara stopped after the first year. One day he woke up and realized he hadn’t thought of her at all the previous day. Then two days passed without thinking of her. Then more. He stopped expecting her to be there. He found ways to take care of himself, to work around her absence, yet he could never truly fill the void she left behind. There was no substitute for the role she had played in his life.

He continued to live mostly on the momentum of his habits. He got up on Tuesday morning (Monday was a minister’s day off) and drove to the church with about as much enthusiasm as someone would drive to an office cubicle for a job counting widgets. He met with people about weddings and baptisms and pasted on his best ministerial smile. He sat through the meeting to plan the sermon with Emily, the music director, and Marlee, the religious education director, and let his experience carry him through.

He waited for the mail in the early afternoon, a highlight of his day that inevitably disappointed. (No engraved invitations to lunch with the governor, no handwritten personal letters, just a few advertisements and newsletters from other churches.) Then he went home, heated up a frozen dinner, ate it off a folding table in front of the TV, went to bed around ten, and the whole thing started again.

Today was a Wednesday, normally a complete throwaway of a day, but fortunately, Paul thought, he had a funeral to plan. It made getting out of bed easier. He entered the church through a back hallway that led to the office. It was already unlocked when he arrived, which meant Julie was in.

Julie had assumed the reception duties at the church after Sara became the minister’s wife. Now in her midforties, she had blonde hair, which she often wore in a long French braid. She had many of the same qualities that had made Sara perfect for the job. She was patient, warm, and interested in people. She was also the gossip hub of the church. Churches have files and records, but most of the real information about a congregation resides in the receptionist’s head. If you wanted to know anything about anyone in the church, it was Julie, not Paul, who could tell you.

Paul stopped in the restroom behind Julie’s desk and examined his face in the mirror. At forty-two, his hair was already salt-and-pepper gray. The hair at his temples had gone completely white, and he was starting to thin a bit at the crown. He reached down and grabbed the spare tire around his waist. It didn’t quite qualify as a “beer belly,” but he was certainly not the trim man he had been twenty years before. That was his real body, of course; this replacement was some kind of mistake. Paul thought the dark circles under his eyes made him look three times his age.

Then he had an even more disquieting thought. Maybe he looked exactly his age. Paul threw some water on his face, then went into his office and waited for his meeting with Stuart Briggs.

When Mary Adams died at age eighty-one, it came as a surprise to no one. The end came after years of slow decline that took her motor skills, memories, and sanity. Then there was the long death watch. She held on, uncomprehending and in pain, for weeks. She finally slipped into a welcome unconsciousness, where she remained for several days before finally letting go. “At least she's not suffering anymore,” people usually said.

Through all of it, Stuart Briggs was at Mary’s side. Mary was Stuart’s first and only love. They had met in high school and hit it off right away, but for whatever reason, Mary never was attracted to him. They never dated. Stuart waited in the background as she dated other boys. He was a guest at her wedding to another man. When her first husband died, Stuart was there, hoping for his chance, but it never came. He waited through a second marriage, which ended in divorce.

After that, Mary came to rely on Stuart’s constancy. He was the person she called when she needed someone to go with her to the movies, to help her with an errand, or just to talk. They became regular companions, but as far as anyone could tell, they never had a physical relationship and it was never a romance, at least not for her.

When Mary became ill, it was Stuart who cared for her. He took her to church on Sundays, pushing her in her wheelchair even as walking became a challenge for him. He was calm and patient with her confusion and mood swings. He visited her daily in the nursing home long after she had forgotten his name. He stayed with her every day she was in the hospital and then in hospice. He was there when she died, holding her hand. Now he was making the funeral arrangements because Mary’s children were scattered across the country in California and Colorado.

He now sat before Paul holding a small scrap of newsprint. It was Mary’s obituary, a short notice mentioning her career as a teacher and her long membership in the church. It named her first husband (“pre-deceased by….”) and said she was survived by her two children and their families. Stuart was identified only as “special friend.” He had loved Mary longer than her husband; longer than anybody. The center of his world was gone, and yet he had no official title to acknowledge his status. When someone says, “I lost my wife,” everyone understands the magnitude of that loss. “I lost my friend” is different. Unless you know the person well, it has no meaning at all.

As Stuart talked about his thoughts for the service, Paul thought about obituaries. When a person you love dies, the obituary takes on an outsized importance. It is the community record that this person lived; she was here; her life did not pass without notice. Yet obituaries are also almost always flat and disappointing. They consist of a dry list of job titles and accomplishments and official connections. But what about the unofficial connections we have in life? Where are the teachers who changed our whole perspective; the mistresses; the dear, dear friends; the ones who worshiped us with unrequited love? What about the ones who got away? The ones we pined for who never returned our affections? Where do they fit?

Obituaries are written in shorthand, sketching out a biography but leaving out all the context that creates a full life. Marital status is a shorthand, but a misleading one. You can be a devoted spouse or a disinterested spouse, an abusive spouse or a supportive spouse. You might have married for love or social status. It is all marriage. Career titles are a shorthand. The deceased held a job, but was it his main sense of pride and identity, or something he dragged himself to every day to pay the bills? You will never know from a death notice. Even seemingly straightforward words like “mother,” “father,”“daughter,” and “son” are shorthand. Was your brother “like abrother” to you, or were you distant or rivals? Was your father the constant presence who taught you to play baseball and took you to Cub Scouts, or was he the man who had sex with your mother and disappeared? Was your relationship with your mother loving or strained and difficult?

The shorthand of obituaries is meaningful to those already in the know—but then, they don’t really need the biography. Our obituaries, our biographies in general, are a show for those who know us the least. Paul thought he had stumbled onto the very definition of what it means to be intimate, to know someone well. It is to understand the meaning of those shorthand words for a particular individual, to understand the ambiguities of a life, the parts that do not fit neatly into boxes.

When he had finished his meeting with Stuart, Paul walked to the cemetery next to the church and sat on the ground beside Sara’s stone, on the plot where he hoped his bones would one day be buried. The cemetery was designed to be peaceful and meditative. It was far enough from the road that the cars sounded like a distant breeze.

“Have you seen Mary Adams?” Paul asked Sara’s slab of granite. “I’m doing her service this weekend. She’s probably with you now.” He paused, imagining but not hearing her answer. “Stuart had a picture of her from when she was young. She was pretty. It was like looking at another woman, another time…. You’ll never be old, will you?”

He sat for a moment, pulling weeds from the grass by his feet.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen to him. People are supportive. They’re all taking shifts bringing him food. But what is he going to do when they leave? I don’t know whether to pity him or admire him. I can’t imagine being that committed to anything. There’s something noble in it.” He sighed.

“God, I miss you, Sara. I just don’t know what I’m doing anymore. You had a way of pointing me in the right direction. My job is to inspire people. How can I do that if I’m not inspired? I don’t need God to send an angel down on a cloud to touch me on the shoulder. But I wouldn’t mind a little spark of inspiration. I just want to wake up to life again, to feel the presence of God in something. I’m just going through the motions, and the members of the church deserve better.”

He sat listening to his own thoughts, feeling the absence of Sara’s replies, until the ticking of the clock seemed to penetrate the walls, calling him back to his normal state of unproductive busyness. He stood and smiled at the stone as if it could smile back at him. Then he walked through the courtyard and back, he thought, to his normal routine.

ANGEL

“Every angel is terrifying,” begins Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Second Elegy.” “But if the archangel now, perilous, from behind the stars took even one step down toward us: our own heart, beating higher and higher, would beat us to death. Who are you?”

The poet describes angels as “mountain ranges, peaks growing red in the dawn of all Beginning.”

PAULENTERED the church foyer still lost in his thoughts. While his eyes were adjusting to the dim light (it took longer these days) he was nearly blind. Across from him, the front door opened, and bathed in the rays of the late-morning sun was a startling vision. It was an angel, a radiant, luminous being. Her long hair, like spun gold, surrounded her in a halo. Her huge eyes, the color of the ocean, were a portrait of childlike wonder and love. For a moment, Paul was so moved by his mystical vision he was tempted to fall on his knees right there and pray to God.

He took a step forward and squinted. As the figure came into sharper focus, he realized his mistake. He was not looking at an angel, nor was it even a woman. It was a young man. He appeared to be in his early twenties. His shoulder-length hair was dishwater brown, not spun gold. It hung forward to obscure his face. He had a slim build, not bony, but more “skinny” than “thin.” He wore a white long-sleeved T-shirt with a picture of the Pillsbury Doughboy in the center paired with tattered jeans. Paul felt a twinge of embarrassment over his mistake—human for angel, man for woman—but his fascination with the being was not diminished.

The visitor ran his finger beside his ear and tucked the wayward strand of hair behind it, revealing his entire face for the first time. Paul had never seen a face so beautiful outside an art museum. A dimple in the chin and the slightest trace of stubble made his jawline masculine. That and his strong cheekbones contradicted the delicate, feminine nature of the rest of his features—the upturned nose and soft lips that curled up at the ends, creating a captivating pout. He had a swan-like neck, and his large eyes—were they blue or green?—were as riveting as they had been when Paul thought they belonged to an angel. Each feature was perfection, and the whole was more than the sum of its parts. He was not at all feminine in his movements. Masculine, and yet too pretty to read entirely as a man.

Paul felt his eyes widen as his pupils dilated. His heart began to race. Could the young man hear it from where he was standing? Who on earth was he? Paul was struck with the desire to take up painting just to try to capture his classical beauty. An angel. An angel had walked in through the door of the church. He was simply the most beautiful work of art Paul had ever seen. He was captivated and terrified by the intensity of the feeling.

“Can I help you? I’m Paul, I’m the minister here,” he said over the sound of his beating heart. He put out his hand.

The young man took it. The corners of his lips turned up into a curlicue smile. Soft hands. A firm handshake. He was a corporeal being after all. “Hi,” he said. “I’m looking for the AA meeting.”

The AA meeting. Well, it wasn’t exactly what Paul had expected an angel to utter. The young man was not looking for a church or a minister. He would go to his meeting and walk out the door and might never appear again. Normally, Paul would have pointed down the hall and said, “Turn left.” Instead, he said, “This way,” and he gestured for the younger man to follow.

“Thank you,” the visitor said, and he smiled again. It was just a typical everyday smile, the kind you’d give to the clerk at the drug store when she handed you your change. One of his front teeth, the third to the left, was slightly crooked, creating a small gap. Paul seized on the imperfection. The young man had flaws. He could need somebody. He could need a minister.

As hard as he tried, Paul could not come up with anything else to say on that walk of a hundred feet.

“Here it is.”

“Thank you,” the visitor said with a small nod, and then he started into the room.

Paul called after him, “If you need anything else, let me know.”

But he was already taking a seat in the circle of recovering alcoholics. Why had Paul said that? “If you need anything else?” He only needed directions. Who wanted lots of personal focus showing up for their AA meeting?

“What am I thinking? He’s a man. A man.” But he knew it was already too late. The vision had been too powerful. It would not leave him.

It was only the second time in his life that Paul had experienced something he truly believed was a direct message from God. The first had not been nearly as intense. When he was a young man, about the age of the mystery visitor, Paul had prayed for guidance about his career. He asked the Lord if he should become a minister or perhaps study business or law. That night he had a vivid dream in which he met Jesus Christ and kissed his hand. He knew immediately upon waking what he was meant to do with his life. He never doubted God had spoken to him through the dream. For years, Paul prayed to God to give him another sign. He longed for a truly transcendent experience, but he never had another dream or vision. Not until now. Paul had no doubt his vision of an angel was a message of some kind, but this time he had no idea what the meaning was.

He went back to his office and tried to think about the eulogy for Mary Adams. He couldn’t. He tapped his pen on the desk and gazed out the window. Wasn’t this guy young to already be in AA? He could help this young man, he thought. He could be his mentor and teacher. There was nothing strange about wanting to help someone. That was all it was, surely. God had given him a sign that this was someone he should notice so he could help him spiritually. Yet Paul sensed his attraction went beyond a desire to be of service. What was it?

It wasn’t sexual, he told himself. It couldn’t be sexual. He was not gay. He had to be feeling something else. Inspiration, a pure appreciation of beauty. There was nothing wrong with admiring beauty where it existed, even in a male form. God had created it. It was divine energy. The guy needed a community, a church home. There was a reason God had sent him through that door right when Paul happened to be standing there. He felt the enormity of fate in the chance meeting. He could not let the young man walk out as though nothing had happened. Somehow he had to find a way to speak to the angel again. He needed to know what these feelings were calling him to do.

He tapped his pen on the desk. The more he waited, the less time passed. How long did AA meetings run, anyway? He left his office and went to Julie’s desk, where they kept the three-ring binder that showed how long each room was in use.

“Do you know when the pavilion will be available?”

“Well, there’s an AA meeting in there now. Did you need it for something?”

“No. No. Not right now. How long are they in there for?”

“They have the room for an hour and a half.”

“That’s how long the meeting goes?”

“I don’t know. I think they clean up after. Why?”

“Just wondering. I’m going to take a walk in the courtyard to work on my eulogy, if anyone needs me.”

He picked up a prayer book and paced into the courtyard. He held the book in front of his face, but the words just danced. He sat down on a bench. From there he could peer over the top of the book and glance into the pavilion window. He knew where the young man was seated and could just barely make out his left side. He was slumped forward with his elbow on his knee. His long hair brushed his shoulder whenever he tilted his head.

Paul suddenly felt uncomfortable spying on an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, so he tucked the prayer book into his pocket and went back into the foyer. He looked at the bulletin board and took down three out-of-date announcements. Then he straightened the pamphlets in the visitors’ rack. That didn’t take much time, so he decided to take them all off the rack and arrange them alphabetically by title. Some of the booklets had pictures but no text on the covers. He decided to place those at the end of the rack. Because it was “Hope Church,” there were entirely too many Hs. He hadn’t left enough space. He took the pamphlets from last part of the alphabet down on a nearby table. He placed a stack of “Welcome to Hope Church” on the rack and turned around to grab “What Would Jesus Do?” and crashed straight into someone, regaining his balance by placing his hands on the other person’s upper arms. It was his angel. They stood with their faces just inches apart. Paul gasped and backed into the rack, causing several copies of “Membership and You” to rain down on the floor.

“Sorry,” the young man said. “I didn’t mean to startle you.”

“It’s…. I wasn’t looking.”

“Well, I was just going to say thanks again for the directions.” He turned away and started to walk toward the door.

“Wait!” Paul called after him.

The angel turned back. He raised his eyebrows and tilted his head. Paul had asked him to wait, and he was waiting. The problem was, Paul hadn’t planned anything to say beyond that one word.

“Here,” he said, handing the young man a pamphlet. “It gives our service hours. You’re welcome to come on Sunday. We have a very nice… a very supportive community. You’d like it.”

“Yeah, sure. Thanks,” he said as he folded the pamphlet and put it in his back pocket. Then he turned and walked away.

That night Paul lay awake in his bed, fascinated and troubled by his vision and embarrassed by his awkwardness around the young man. He replayed every moment, the angel stepping forward and becoming a man, the way he looked when his face was fully revealed, the surprising affection Paul felt on discovering the small gap in his teeth, the warmth from his body when they crashed by the literature rack. He tried to convince himself that his appreciation for the young man’s beauty was purely aesthetic. He wanted to gaze on the face again the way he appreciated the beauty of other forms of nature—an expansive canyon or a sunset over the mountains. But human beauty was different. A scenic vista created appreciation and wonder, but not longing. For the stranger, Paul felt longing. Some part of him ached to be in his presence again. He knew, as well, that simply being near him, seeing him, would not be enough. Seeing him again could only increase the longing.

In the privacy of his room, he allowed his mind to explore the nature of this ache. He stopped trying to critique and explain. He came back to the moment when their bodies touched, when their faces were so close, his hands on the visitor’s arms. He imagined their lips coming together, his hands exploring the other man’s chest. He imagined at first something ethereal—the pair bathed in white light, communing with an angel. But his musings gave way to something much more physical and sweaty, a pure masturbatory fantasy of limbs and tongues and powerful erections.

As he lay in the glow of his climax, he wondered who he was and what this all meant. He thought back to his youth and the forbidden Playboy and Penthouse magazines he had kept hidden in the crawl space. He remembered the time one of his teachers bent a little too far down and accidentally exposed her right breast, and how that image played into his fantasy life for years; how all-consuming his high school infatuation with Sally Guthrie had been, how nervous he had been about that first kiss and how much persuasion it had taken to get her to third base.

He thought about Sara, how lovely her shyness about her body was. How much he had longed to ravish the paragon of Christian community, to become the only one to unravel her secrets. He loved the freckles that dotted her skin (and that she hated so much), her little teacup breasts (she called herself an “ironing board”), and the undeniable intrigue of the ginger hair that decorated her nakedness. These had not been substitute fantasies. He had not desired women because he thought he was supposed to. The attractions had been as real as the wind and the tides, a true force of nature. So what was this? What was this?

The following Sunday, Paul surprised the greeters by joining them in the foyer. He said he’d decided it was much more welcoming if the minister took the time to greet all the newcomers personally. His eyes were wide, and he watched each person coming through the door with a sense of anticipation. The young man never arrived.

“It was nice to see you out there greeting like that,” Julie said after the service. “It was a good idea. A lot of people had good things to say about it. Since Sara died, well, it’s just nice to see you so engaged again. Like old times.”

He greeted the visitors again the following Sunday, and the two after that, and each time he held onto the nervous expectation that his angel would appear. He never did. Each Wednesday afternoon Paul found something to do in the pavilion or the lobby. He watched the alcoholics file in and leave. The visitor was not among them. On every occasion, Paul was both disappointed and slightly relieved. He started to wonder if he had imagined the whole thing. Perhaps the young man did not exist at all.

HERE ISTHE CHURCH, HERE ISTHE STEEPLE

Archaeologists think they know what ancient people believed. Ancient tall things were supposed to be monuments to the divine and our modern structures monuments to mankind. We’ve become self-centered and arrogant. That’s what they say. But is that true? The Egyptian pyramids were tombs of the notable people of their day. We inscribe our large buildings with Masonic cornerstones and mythic symbolism. Future archaeologists might think the Sears Tower was built to take us closer to God.

If man was created in God’s image and God makes mountains, isn’t it natural we’d try to build mountains of our own? Weren’t all these structures created out of the same human desire to climb? Building a cathedral is building a mountain. It is the creation of an edifice so large and grand that we are humbled in its presence. Could it be that, paradoxically, the magnificent churches with grand steeples represent a Christianity of humility, not hubris?

PAULWAS gazing out the conference room window into the foyer and the spot where he had first seen the young stranger. He pictured himself reaching out to him, touching his cheek.

“I’m not saying we shouldn’t fix it. I’m just saying it shouldn’t be our priority.”

Paul’s attention snapped back to the room. Mike Davis, the church board president, was serious and pragmatic. Mike was always the alpha in any meeting. He was a business owner who had focused so much of his time and attention on his industry that he couldn’t quite keep his focus on a wife. He was now on his third.

As with most churches, the church board was made up entirely of volunteers. They almost always ran unopposed, so the main qualification was a willingness to do the job. The church didn’t have to pay them, but that also meant no one could fire them. It was always hard to give people enough appreciation to keep them interested. The rotating boards changed the tone of the administration every couple of years. Sometimes there would be a volunteer who couldn’t get around to doing any work but who didn’t want to relinquish the title and the position, and everything would grind to a standstill. Other times an overly enthusiastic volunteer would put in so much time and energy that she would start to feel resentful, and she’d end up quitting the church entirely.

Mike brought a serious business tone to the board. He believed strongly that the principles of corporations should be applied to the church. Under his leadership, the board had created a mission statement and posted it everywhere. Their priority was “growth,” which they equated with success. Paul had nothing against growth, per se. It would be good for his ego, certainly, to see the pews full each Sunday. But he was uncomfortable with the implication that worship was a product to be marketed the same way you’d sell a soft drink or a pair of designer jeans. It seemed the entire culture had become permeated with a marketplace mentality, and church should be the exception.