Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

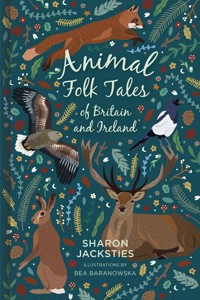

Stories and animals have long travelled the same routes. Through our heritage of charming, quirky and profound tales, you will find yourself re-acquainted with Britain's wondrous fauna. Find out how hedgehog ended up with spines and what makes him scuttle so fast, discover how pigs saved a prince from leprosy and why the wealthy lord was so intent on capturing the black fox. Sharon Jacksties' wonderful book combines traditional stories, little-known zoological facts and true anecdotes to create a treasure trove of stories for animal lovers of every kind.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 282

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Fiona and Felix

First published 2020

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Sharon Jacksties, 2020

The right of Sharon Jacksties to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9780750994460

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Europe

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Eric Maddern

Introduction

From the Horse’s Mouth (from the telling of Hugh Lupton)

1 Running Wild

Wolf and Fox, Enemies of Old

The Black Fox

Hare Here on Earth

The Hare and the Black Dog

Deer Dreaming

Deer Wife, Deer Son

King Arthur and the Ermine Cloak

How Ferret Came to Be

The Grateful Weasel

St Columba and the Squirrel

Bear Skin

2 Field and Farm

As Drunk as a Pig

How Pigs Saved a Prince

The Thieving Goat

The Cattle from the Lake

Faithful Gelert

Cat against Rat

The Donkey in a Basket

Another Christmas Donkey

Jack in a Sack

But One Horse Missing

3 Making Waves

Whale Music

How the Narwhal Became

Saved by a Seal

The Origin of the Selkies

The Selkie Suitor

The Selkie Bride

Gotham’s Eel

Davey Kisses his Catch

The Otter King

The Little Crabfish

A Crabby Curiosity

Oldest of the Old, Wisest of the Wise

4 Creeping, Crawling and Scuttling

How the Birds Helped Hedgehog

Robert the Bruce’s Spider

How Spider Became Wolf

Mischievous Moles and Mole-Catchers

The Grateful Ants

A Rick of Rats

Missy Mouse Marries the Moon

Snake in the Grass

God’s Bargain with the Worms

5 On the Wing

The Fly and the Flea

Bat Woman

War or Peace?

The Children of Lir

The Swan Captive

Robin’s Red Breast

Gotham’s Cuckoo

How the Birds Got Their Colours

How Magpie Taught Nestbuilding

What Swallow Tells her Chicks

The Rooks in the Pear Trees

The Honey Bees and the Snow-White Hare

Redstart Brings Fire

6 Reclaiming the Right to Roam

Braving the Boar

Boars’ Break for Freedom

The Grateful Wolf

The Return of the Wolf?

The Sea Eagles’ Revenge

The Return of the White-Tailed Sea Eagle

Lynx the Most Beautiful

The Return of the Lynx?

The Crane Skin Bag

An Eyeful of Crane

The Return of the Crane

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

WITH THANKS TO Giles Abbott; Damon Bridge; Fiona Collins; Joe Crane; Jem Dick; Sonia Guinnessy; Halsway Manor, Somerset; Simon Heywood; Lorcan O’Tuathail; Lisa Schneidau; The Shipwreck Centre, Arreton, Isle of Wight; Iris Skipworth; Yvette Staelens.

Most of all I would like to thank Debbie Felber, who wormed her way into story sources I never knew existed, shape-shifted into a mole amongst archives not available to ordinary mortals, beavered away at finding me unusual stories, squirreled the best of these away, and badgered me into staying as close to the ‘originals’ as possible!

Foreword

IT’S A LONG road we’ve shared with wild animals. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors closely observed the creatures of their world either to hunt them, or to hide from them, or to tune into their spiritual teachings. Thus animals have been fellow travellers and helpers on humanity’s evolutionary path since the beginning. They not only provided nourishment, they also gave fur, sinew, skin, bone and horn to make clothing, tools, weapons, instruments and artefacts. They were treated with great reverence and thanks was always given for the lives taken. It was also believed that wisdom and power could be found in their unique character, so animal totems were a key part of early cultures.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that most early stories were about animals: about how they made the sun, the moon and the stars, how they came to be, how they created the first people, how they brought fire. In this creation mythology people and animals often transform into each other. In their ritual re-enactment of the founding dramas, early human actors would dance their spirit animal to life and so be imbued with its transcendent power.

That early culture is long gone in Britain. Indeed, post-industrial twenty-first-century life seems to be its polar opposite.And yet vestiges of it remain, not only in the enduring attraction of hunting, fishing and blackberry picking, but also in the stories, in the folktales, myths and legends of these islands. In these traditional hand-me-down narratives, animals speak, humans transform into creatures and beasts are often the wise and knowing ones. The tales express our long and undying fascination with the wild beings that share this wondrous world of ours.

In this book Sharon Jacksties has gathered together an outstanding collection of time-honoured animal tales from all parts of Britain and Ireland. She’s included a good number of classics and dressed them afresh in new clothes. We hear, for example, about Finn Mac Cumhaill and his beloved deer wife and otherworldly son, Oisin. There are selkie tales from the Western Isles of Scotland and the old Welsh story of how Arthur’s men found Mabon, son of Modron, by asking the Ancient Animals. We learn how Arthur’s end was hastened by a snake in the grass, how four kings’ children were turned into swans, how the nightingale came by its golden voice.

Sharon has also, with the help of her badger-mole-beaver friend, found lesser-known stories and brought them to life in these pages. Here you can read how the spider turned into a wolf, how the princess became a bear, how the redstart brought fire. And so many more. This rich feast of tales is spiced up with enchanting rhymes, song lyrics and old sayings. And in the last chapter she weaves into the tales accounts of rewilding attempts to bring back some of the animals that have died out in Britain – the lynx, crane, boar, sea eagle and wolf. Her love for the creatures of the wild shines through in all of these stories.

Sharon Jacksties is a consummate storyteller and this comes across in her graceful and poetic retelling of these tales. She has a wry sense of humour and an eye for the absurd. In this book she has created a blend of tales highlighting the bizarre quirkiness of the folk tradition as well as the wisdom and insight that lies therein. More than anything, what comes across is her passionate commitment to story and the huge and human compassion she feels for our animal kin. Read this book and it will rub off on you!

Eric Maddern, Cae Mabon, 2020

HOW BEWILDERED MY parents must have been, completely uninterested in animals as they were, to have produced two animal-besotted children. Long before becoming a storyteller I was the devotee of every zoo and wildlife organisation within reach, even corresponding as a young child with our famous animal-collecting pundit and author, Gerald Durrell.

The writing of this book, however, has taken me on a very different journey. It is the stories themselves that have bestowed glimpses of why and how some of our native species are better better represented than others in what remains of our traditional canon. The questions that arise from traditional stories are, for me, an enhancement of their ability to create wonder. Despite all folk tales (unlike their mythological cousins) having the characteristically clear-cut endings that promote a sense of satisfaction, it is also the absences and omissions that provide a concurrent interest. For instance, it was a surprise to discover that some of our more iconic animals are so under-represented by fictional story. Bears and wolves, for example, are mostly to be found in the recent Germanic imports from the Brothers Grimm. Earlier Norse stories containing these major predators could arguably be later described as British given that although they were first told by incomers, they were heard and repeated by the incumbent population that itself was made up of previous settlers.

My work as a storyteller has involved many years telling to the very young, often in inner cities where children believe that milk originates from a lorry. Yet even three year olds grow wide-eyed with awe and fear at the mention of bears. They have never seen one and their parents and grandparents, many of whom are from all over the world, have probably not seen bears either. How to account for their reaction when the teller, through neither tone nor description, has inferred nothing untoward? Despite much research, only two British bear stories were found in time for publication. ‘Bear Skin’, rewritten here, is almost certainly Scottish, possibly Norse in origin/influence, yet part of a genre that has produced many forms of this story throughout Britain. Bears have not lived here for more than a thousand years, but this time-warping story happily presents us with a bear ensconced in a palace garden’s wheelbarrow!

The bear story that was not included for reasons of space, is a little-known Arthurian tale. The name ‘Arthur’ means bear and it is no coincidence that this hero of Britain’s most important story cycle is represented by this most powerful of animals. Our hero king, most celebrated for uniting a warring land containing some populations ambivalent towards the new religion of Christianity, is given the name of an animal most significant to what by then must have been vestigial pagan beliefs. In Brythonic Celtic pagan mythology, the bear chases away winter and summons the returning sun for the spring equinox. In this story, a huge, unknown young man appears at court from the forest and asks to be knighted. Arthur takes an instant and most uncharacteristic dislike to him and finds excuses to avoid doing this – one being that nobody knows who the youth’s father is. At that point a bear breaks out of the menagerie and rushes up into the tower, where the ladies of the court were to be found. Sir Gawain, Arthur’s champion, is also there but can do nothing as he is unarmed. The youth wrestles the bear into submission and throws him out of the window. Arthur then has to knight the young man, but maintains his hostility and distance – an implication being that the newcomer is himself half-bear and that Arthur will not tolerate another in his territory.

There is another echo of the mythological divine in ‘Bear Skin’ in which a father overprotects his virgin daughter, who escapes him by becoming a bear. The peoples of this land once listened to the classical tales brought by Roman invaders and settlers, in which the bear is dedicated to the Virgin Goddess Artemis, who was known to manifest as a bear.

The shape-shifting between human and animal forms, which contributes so much to the magical element in our traditional tales and folklore, derives from the beliefs and shamanic practices of our animistic ancestors. It is cultural memory preserved in story like a fly caught in amber. When sophisticated pantheons of pagan deities evolved, they took on these powers. Some of the best examples of these ancient beliefs can be found in our myriad stories about hares. The ancient Irish hero Oisin pursues one of these creatures into the Other World, only to find her transformed into her true shape and enthroned as a goddess. In a later age, Christianity disempowered these animals by subverting them from agents of the divine into those of evil and witchcraft whence, in their folk tale form, they continue to delighted us with a frisson from the Dark.

Our vast lore of selkie stories – those hybrid beings that are neither wholly human nor wholly seals – testifies to our fascination with both our need and inability to distinguish ourselves from beasts. During these times of increasing concern about our relationship with Nature, there is a growing interest in animals. May this book play a small part in renewing the wonder that is their due and inspire us to contribute to their protection.

Sharon Jacksties2020

From the Horse’s Mouth

From the telling of Hugh Lupton, storyteller, poet, author, teacher

There was once a king who was as kind as he was wise and as wise as he was kind. His sons and his people loved him.

One evening he and his court were feasting when he saw something glimmering on his food. Raising it on the tip of his knife, he held it towards the candle to see it better. The hair shone silver-white in the golden light. Furious, the king ordered that the cook be brought before him. All were silent as they waited for the cook to appear, it was so unusual for their king to display bad temper.

The king sat there, his darkened face fixed on his plate. The hand that held the knife with the silver hair still clinging to the blade, was trembling. The fearful cook came silently into the hall. He stood beside the king, who did not notice him at first until he coughed gently to let him know that he was there. The king looked up, into the face of a young man. The cook had glossy black hair; it would be years before any turned grey. The king had found one of his own hairs on his food. He had grown old without knowing it. ‘And they think me wise!’ he smiled to himself.

Now that he knew that he was approaching the end of his life, he wondered which of his sons to leave his crown to. All three were clever young men, so he decided to set them a task.

‘Bring me the least truthful thing in the land and bring me the most truthful thing in the land.’

The eldest went first. Before long, the king heard the sounds of a struggle outside his chamber. Suddenly the door was kicked open and the eldest prince burst into the room. Under one arm, squirming and protesting, was the prime minister. Under the other arm, protesting and squirming, was the archbishop. The king began to laugh. He laughed and laughed until he could barely speak. At last he managed to gasp,

‘Very good, my son, very good, but which is which?’ And fell to laughing again.

The middle son went next. He was soon back and placed before his father a portrait and a mirror. The king looked at the image of himself as a young man in his prime. Then he looked at his reflection. He knew he didn’t look like his picture any more, but when he looked in the mirror he knew that he didn’t feel as old as the old man who stared back at him. He looked from portrait to reflection, from reflection to portrait. Which was true – how he looked or how he felt? Tears ran down his cheeks as he said, ‘Very good, my son, very good, but which is which?’ And he fell to weeping again.

Then the youngest son set off. He returned when the courtiers were all assembled for the evening meal. There was a gasp when they saw what he held in his hands. It was a horrible sight: in one hand was a withered blackened strip of flesh and in the other was a raw, bleeding, still steaming horse’s tongue, fresh from the butcher.

‘Do not ask, Father, which is which, for it is easy to tell. In one hand I hold a human tongue that I cut from a corpse hanging on a gibbet. Of all God’s creatures, Man is the only one that can lie. Of all of God’s creation, the human race is the least truthful. In my other hand is the tongue of a horse, one whom we call a dumb beast. But, oh Father, if we could but understand the language of the birds and the beasts how wise we would be when we listened to those who cannot lie.’

When the youngest son ruled the kingdom, he was wise enough to always have his brothers’ company and help at hand.

Wolf and Fox, Enemies of Old

Fox set out on a winter’s night

He called on the moon to shine so bright

He’d many a mile to roam that night

Before he reached the farm – o! – farm – o! farm – o!

He’d many a mile to roam that night

Before he reached the farm – o!

On he ran to the farmer’s pen

Where ducks and geese were kept therein

‘A pair of you will grease my chin

Before I leave this farm – o! farm – o! farm – o!

A pair of you will grease my chin

Before I leave this farm – o!’

Every evening the farmer would drive his oxen home. It didn’t matter how hard they had worked during the day, the farmer always complained at how slow they were. Dragging their hooves and stumbling, he never thought that he had driven them too hard. He would sometimes curse them, saying, ‘By God, I wish the wolf would eat you!’

Though far away on the hillside, Wolf, with his keen hearing, heard this curse. He wasn’t the only one: Fox, always unseen and often too close for comfort, also heard it and much else besides. One hungry night Wolf was waiting by the oxen’s pen.

‘I have come to claim what is mine.’

‘There is nothing of mine that is thine,’ said the farmer.

Wolf explained how he had come to collect the oxen that had often been wished to him, and the farmer argued against this. As neither could agree, they decided to take the matter to a judge. At that moment, Fox, who had been secretly listening as usual, materialised out of the dusk and offered to judge the case. The others readily agreed, even though Fox said that in the interests of confidentiality he would have to speak to each of them separately.

The farmer was taken aside first and Fox promised him that he would ensure that Wolf did not take the oxen – for a small fee, of course: ‘Just the one goose for myself – oh, and a duck for Vixen.’

The plaintiff was nonplussed for a moment, being used to Fox stealing from him rather than him being put in the position of donor.

‘A goose and a duck – small price for a pair of oxen, I think. But if you have a better plan, I quite understand,’ said Fox, knowing full well he could always come back later.

Planning was not the man’s strong point and he felt more comfortable leaving that to others, even if this meant that a fox was doing his thinking for him. A second bad bargain being struck, Fox trotted off for his confidential interview with Wolf.

‘Farmer has reconsidered his hasty words and wants to make you an offer. A pair of oxen is a powerful great mouthful for one wolf. It would take you a month to eat the first and during that time you would have to be providing fodder for the second. It’s more trouble than it’s worth. Farmer has offered you a whole round of cheese instead.’

Wolf began to drool with hunger, a cheese would be less trouble than butchering an ox. He could think of it as a starter and maybe come back for an ox at a later date, now that he knew where they lived. Fox saw him hesitate: ‘If you’ll just follow me, I’ll show you where the cheese is kept to keep it fresh.’

Fox led Wolf to the well, knowing that the full moon would be reflected in it at exactly that time. Wolf peered into it and saw that a huge round of creamy cheese lay in its depth. A thin strand of drool stretched towards it, breaking the surface of the water. The cheese shivered invitingly, but how to reach it? Fox pointed out the buckets and handle and explained that if they took it in turns to sit in a bucket, their weight would bring them down to the cheese.

‘It might be a bit slippery with that water keeping it cool. Could be tricky lifting it – you wouldn’t want it to roll away from you like some great wheel,’ said Fox. ‘Perhaps I should come down and help you with it?’

At that Wolf felt a little wary. Supposing he went down and handed it to Fox, what would prevent him from running off with it – even bowling it before him like the wheel he had mentioned? But if Fox went down first then he would have to pass it to Wolf. Fox was invited to do this and he set off in one of the buckets. Wolf waited till he had reached the bottom before he scrambled into the other bucket. Of course, his descending weight made Fox’s bucket rise. As they passed each other Fox said, ‘There’s always somebody on the way up when there’s someone on the way down.’

Wolf stayed at the bottom of the well looking for the cheese until the moon passed over, and Fox collected his promised goose and duck. Not long after that, he collected a few more that had not been promised.

The Black Fox

‘Black Fox’ is a term given to an animal with a black brush and legs, sometimes a black muzzle or ears too. There have only been a handful of totally black foxes recorded in Britain.

There was once a lord who was the greatest landowner in the region. His estate spanned moor and coombe down to the North coast and the South. Often he would ride his favourite mare, Midnight, up to the highest tor to look in all directions at what was his. To the East and West his land stretched so far that he couldn’t see its limits – except for that one little dark patch on the rolling gold of the moor, before the woods dipped down into the coombe behind it. Whenever he saw that his guts twisted inside him because that tiny patch was a little cottage that he didn’t own, and couldn’t for all his trying.

There that cottage lay, a freehold blot on the landscape of all he possessed. His grandfather had given it outright to its owner, and the deed lay signed and sealed with the county sheriff. It was so long ago that people differed about the story behind that gift. Some said that it was in return for the favour she had done, saving his life after a hunting accident. Some said it was for more favours than that. What was hardest to believe was that the woman, old now beyond reckoning, was still alive – but nobody doubted that Dame Biddy was a healer and had been the best bone setter in the county. Others whispered what they dared not say aloud – that Dame Biddy was a witch. If that rumour had reached him, he didn’t wonder at it, as on the few times he had visited her, asking to buy her out for far more than the old cottage was worth, he had spent the following night in agony, gripped by gut-wrenching pains.

One day, the lord rode into town for the market. He noticed a stranger, a haughty young woman with red hair and a sinuous grace about her. He tried to catch her eye, but she slipped around the stalls in such a way that he couldn’t get close enough. Whenever he caught a glimpse of her and set off in her direction, she was gone, only to appear suddenly elsewhere. However, he soon forgot about her when a servant rushed up to him and whispered the news that Dame Biddy had died.

The next day he galloped over to the cottage, but reined Midnight in with a savagery she never deserved. There was smoke rising from the chimney. When he rode closer he could see washing on the line – two pairs of black stockings and a russet cloak. There came a sudden gust and the cloak fought it, turning itself almost inside out, revealing its black lining and startling the mare. As she bolted, he seemed to hear harsh, sawing laughter coming from the cottage. Somehow that mocking bark of a laugh deterred him from calling in person. It was his servant who told him that Dame Biddy had left the cottage to her great niece – and once more there was nothing he could do about getting it for himself.

It was strange, in those distant days, for a young woman to be living by herself. Many admired or even envied her independent ways. Footloose and fancy free she seemed, with a flashing grin for those she passed on her jaunts. She trotted along the lanes on fast, silent feet, her red hair sleek and glossy and her bright eyes sliding into that quick sly smile, so that none could have said what colour they were.

Everyone knew that she didn’t work but no one knew what she lived on. From time to time she would pass the lord in a narrow lane and it irked him that she had eyes only for his horse and not for him. It took a while for him to realise that it was she who had moved into what should have been his property. He hated her for this, but could not admit how much he was attracted to her. Unable to stay away at last, he visited on the pretext of offering her work at the big house. He found her in the garden. Her only answer was to bark that harsh laugh at him, her crimson mouth drawn back over pointed white teeth. Then she ran, leaping the garden wall to get away.

So the lord resorted to his one pleasure, that of hunting, the only thing that he had shared with his grandfather. Although he kept the best pack of hounds in the county, he would sometimes be invited to join other hunts. These were the only occasions when he would meet his neighbours, landowners like himself but none as wealthy. That season they were all talking about the highway robberies that were taking place on the moor, and of a highwayman who seemed to know exactly where and when the coaches would be passing even though routes and times had been varied.

The lord was more troubled by his mount, so unusually listless. Midnight, always ahead in the field, had hung back and barely cleared a gate. When he returned home he questioned the grooms. One admitted to finding her in a sweat first thing, even though she had been thoroughly groomed the night before. The grooms took it in turn to watch through the night from the hayloft. They never saw anything, although some mornings still found Midnight sweating and restless though tired. Fearing their master’s anger, they never mentioned these occasions, and rubbed her down so that her coat was as glossy as it should be. One of the cleverer grooms took some long hairs from her tail and attached them lightly to her tack, but on those troubled mornings, they were found to still be in place.

When the hunting season was over, the lord had nothing to distract himself from thinking of that cunning young woman he so hated to be fancying. Then the solution occurred to him: he would marry her. She would be his and as everything belonged to the husband after marriage, the cottage would also be his at last. He didn’t notice how Midnight’s head drooped and how she stumbled as he rode to that lonely dwelling. He was in the cottage and as the door swung behind him, the offer was out of his mouth. Even he could see how agitated the woman was and he laid a hand on her arm. She bit, hard. Unbelieving, he heard bone crunch before he tore his hand from her mouth. Then she was gone, escaped past him. His rage burned fiercer than his wounded hand.

That night there was a fire. Nobody knew how it started, or if they did they weren’t saying. That cottage burned down stock and stone. Nobody was sure what those black greasy remains had once been. Silently they watched the lord poking them with his ebony cane. If anyone noticed a sprinkle of sharp white teeth amongst them, nobody said.

On the first day of the new hunting season a large black fox was sighted. All day the lord’s hounds chased it, without seeming to get any nearer. It was started by the next hunt and the next, but the pack never seemed any closer to making a kill. Before any other fox could be sighted, the same black fox always appeared. Some said the brush was too slender for a fox’s – this had to be a vixen. Some said that no vixen was ever that large, that this animal was bigger than most dog foxes. The season wore on and that fox grew bolder and bolder. It would lead the pack on through boggy land where some were lost even though their quarry skimmed along that treacherous ground unharmed. The lord would whip hounds and horses beyond endurance and some were lost or injured that way too. Still he hunted on through the season with only half a pack, determined that however few remained would tear that beast apart before his eyes.

On the last hunt of the season, the black fox made sure its scent led to the stone wall that surrounded the garden of the burned cottage. Hiding behind the wall, it waited until the lord rode up. Then with one leap it was on top of the wall and at eye level with its hunter. A sly look, a flashing grin and Midnight reared, throwing her rider. This time there was no Dame Biddy to set his bones. The lord never regained his senses, but it was clear from his fevered cries and mutterings that in his mind he was still hunting the black fox until the day he died.

Hare Here on Earth

This tale has been inspired by a recording from Giles Abbott, storyteller, who was told it by a lady from the gypsy community. It is written here with Giles’ kind permission.

Long ago, when Time was new, all things were alive and all creatures spoke to each other. Sun and Moon, those most glorious of beings, showed their celestial love by creating a daughter. Hare leaped and bounded across the heavens, zigzagging her way between one parent and the other. Every time one of her paws touched the sky, a star appeared. Time smiled to see how her increase was measured across the sky in countless silver tracks.

Sun and Moon smiled to see how strong and fast their daughter had become, how tireless and nimble. Hare had reached her full strength. One day – or was it night? – she looked down and noticed Earth for the first time. Earth felt her gaze and looked upwards at the delicate paths of silver that followed this magical creature as she danced about. The moment when Earth noticed Hare, was the moment they fell in love.

Hare bounded off to tell her parents the wonderful news that she had found a lover, and one, moreover, who requited her feelings. Sun and Moon asked who she was considering uniting herself with, and Hare proudly told them that it was Earth. Her parents were appalled. How could their celestial daughter decide to have anything to do with a creature so base, so dense, who was incapable of producing any light? They told her that they would never have anything to do with her choice, and that if she persisted, they would not bless this shameful liaison.

But Hare was in love and hurt that her parents’ love for her did not exceed their misplaced pride. She decided to leave the sky forever and live with her lover. From that day – or was it night? – to this, she has stayed on Earth. She became the totem animal of love and fertility, and was venerated as the Goddess Oestra. She gave her name to our spring festival of Easter, and the female hormone oestrogen. Trusting that her consort will protect their children, she doesn’t make a home or burrow for them, but leaves them pressed close against the ground. During the spring equinox her children dance upright to give Sun and Moon an equal chance to see their grandchildren.

The Hare and the Black Dog

From the fifteenth to the seventeenth century, most people in Britain believed in the widespread practice of witchcraft or, if they didn’t, were wise enough to remain silent. Many hundreds were burned or hanged for this ‘crime’. It was believed that their magical powers enabled them to take on the form of an animal, often that of a hare. As the vast majority convicted of witchcraft were women, it is not surprising that they were associated with an animal that was revered as a manifestation of the goddess of fertility in the old religion. Queen Boudicca of the Iceni tribe in East Anglia would release two hares from her robes as a gift to the Goddess and a source of divination before a battle. It was in East Anglia where most of the witchcraft trials and death sentences occurred.

An example of this kind of trial can be seen in that of the conviction and hanging of a woman, unusually named Julian Cox, in 1663. The testimony of a huntsman, amongst others, was enough to convict her. He had started a hare that, after a long chase, took refuge in a bush. When he went around it, he found an old woman on all fours who was too out of breath to speak. It was obvious to him (and everyone else) that she had been the hare he had been hunting.