9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

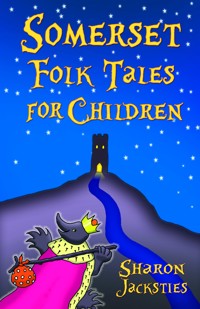

These Somerset tales, newly collected or retold with a strong sense of the land and the waters that shaped them, reflect our enduring interest in the natural landscape. Let these stories from the Summer Lands take you on a journey: across wind-wild moors that plummet to treacherous tides traversed by sea morgans; on a scramble from gorges shaped by the Devil's spite to caves dwelled in by bitter witches. Discover ancient mines and dragons' haunts, and emerge into forests and fields to be befriended by bees or bedevilled by fairies; then stroll beside ancient waterways, where willows walk and orchards talk. From Gwyn ap Neath to Joseph of Arimathea, your travelling companions will meet you from legend, history and living memory – from the places where they were once known best. Sharon Jacksties has a sharp eye for the landscape of Somerset and the seen and unseen stories that it holds, a sympathetic ear for the dialect of the South West, and a playful wit that brings this collection of tales to vivid and delightful life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

For Joe who has always said that I could and should, and for Jem who has lived with the consequences

For Di and Dave, and their warm Somerset welcome

For my sister Debbie, without whose expertise and boundless generosity this would not have been possible

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

One THE SALT SEA STRAND – THE BRISTOL CHANNEL

The Monster Fish

The Sea Morgan’s Child 17

Big Blue Ben

Local Hero Captures Slavers

The Laying of Lucott

St Decuman and the Holy Well

A Dragon Tamed

Creature from the Swamp – a Prehistoric Discovery

The Fairies and the Farmer’s Cattle

Two THE FERTILE GROUND – FIELDS AND ORCHARDS

The Golden Apple

As Sweet as Honey

Clever Betty

Saving Baby Bacon

The Fairy’s Midwife

The Brave Midwife

Unlucky Jack Finds his Luck

Three THE INLAND SEA – RIVERS, RHINES AND THE SUMMER LANDS

A Battle Most Unholy

Losing the Battle but not the War

The King of the Moles

When the Good Lord Made the Animals

Yeovil’s Giant Hay Thief

Eli’s Eel

Four THE CURVED HORIZON – HILLS AND MOORS

The Dragon of Shervage Wood

The ‘First’ Hedgehog

Gwyn ap Nudd

St Collen and the King of the Fairies

The Birth of St Bridget and her Mission in Glastonbury

Joseph of Arimathea and the Holy Grail

King Arthur and the Tor

The Death of Arthur

The Once and Future King

The Origin of the Pixies

Five ROOT AND BRANCH – WHAT THE TREES KNOW

The Elder Tree Witch

Why the Willow Has a Hollow Heart

The Apple Tree Man

The Haunted Oak Tree

The Cruel Ship’s Carpenter

The Somerton Murder and the Hanging Tree

The Legend of the Glastonbury Thorn

Six STANDING STONES, RUNNING WATER

Goblin Combe

King Bladud

The Witch of Wookey Hole

The Leaping Stones

Stones Placed to Please

The Devil’s Stony Countenance

The Devil and Cheddar Gorge – Another Unfinished Masterpiece

The Devil turns to Building

The Wedding at Stanton Drew

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks to the following:

Jem Dick, illustrator; Paul James and Mary ‘Biddy’ Rhodes, Halsway Manor; Kennedy-Grant Memorial Library, Halsway Manor; Les Davies, ranger; Pete Castle, storyteller, musician; Harry Giles, acting divisional engineer, Somerset River Board; Les Cloutman, naturalist and ancient archaeologist; The Langport Ladies’ Circle; Langport Senior Citizens’ Club; Langport Library Staff; Becky Wright; Eli’s (aka the Rose and Crown) Huish Episcopi; Gail Cornell, astronomer and writer; and Diane Shepherd.

INTRODUCTION

Somerset is my adopted county, and being an incomer has given me the privilege of seeing it with new eyes. Although I have lived here for nine years, the familiar has never yet become invisible, and not a day passes without my continuing to notice the beauty and variety of its scenery.

Having been a professional storyteller for more than twenty years, I was naturally eager to make an in-depth study of Somerset’s stories. Part of this process involved distinguishing those that were shared with other places from those which this county could claim exclusively as its own. The more I looked and listened, the more aware I became of the huge role that the landscape has played in shaping this county’s traditional stories.

My work with local groups, especially amongst the older people of the region, reinforced my fascination with the links between the traditional and mostly anonymous stories of the past, and the living present. Often the theme of a traditional tale would unlock the tongues and memories of the listeners, and I soon noticed that place was as important a trigger as subject matter.

Their joy at being listened to, and the generosity with which they shared stories – personal, family, regional, folk and legendary – inspired me, by nature and training an oral practitioner, to write this book.

This generosity has been mirrored at Halsway Manor, the National Centre for the Folk Arts; this residential centre, in the heart of the Quantock Hills, owns an extensive archive of Ruth Tongue’s manuscripts – one of the most important collections of local stories, songs and folklore in the country. The centre gave me unrestricted access to their library and permission to reproduce her work, some of which has not been generally available before.

If I am able to repay all those local people who have supported me, by reminding them of tales half-forgotten or by being in some small way an exponent of our heritage, I shall be more than happy to bear any retribution meted out by historians, archaeologists and naturalists!

As the idea of this book took hold, I began to realise that, of all the counties in England, Somerset boasted the widest range of landscapes; later, I discovered that Ruth Tongue had reached the same conclusion:

Rivers and rhines and cleeves and mines

Heather, beech and Severn shale

Cob and thatch where summer shines

Open headland to have the gale …

Somerset bred and Somerset born

Children of oak and ash and thorn …

Somerset born and Somerset bred

Cave and swallet and withy bed

Meadows a-bloom and orchards a-blow

Shining sea where the tides do flow

Purple hill for the hunting horn

Forests of oak and ash and thorn …

This variety has informed the shape of this book, with each chapter being dedicated to a particular landscape. Thus the settings naturally chose the stories, and, had space permitted, there could have been many more.

As I explored plot and place, it became increasingly clear that Somerset offers the unique as well as the extraordinary and the grandiose. Perhaps its most famous landscape feature is the Cheddar Gorge, the deepest in Britain – and how this was formed is described later.

A less well-known example, but just as remarkable, is its ‘inland sea’, the region we now call the Somerset Levels. Its many rivers empty into the estuary of one of Britain’s major waterways, the Severn. This vast inland sea used to cover an area of up to 400 square miles, its depth determined by seasonal rainfall, the distinction between its sweet and salt waters blurred by tidal surges. From north of Glastonbury to south of Ilminster, this formerly flooded landscape has left its legacy in the impossibly smooth contours of the water-rounded hills, which look as though they were shaped by a giant ice cream scoop.

Recent discoveries indicate that, more than 6,000 years ago, this was the first place in the world where people were managing their wetland habitat. Conquering the struggle of land versus water has, over the millennia, given this county the largest area of man-made land in Britain.

The floodwaters still rise along the rivers Axe, Brue, Cary, Huntspill and Parrett as they flow towards the Bristol Channel, whose tidal surges funnel the floods upstream. The name of the tiny village of Hornblotton recalls the villagers’ ancient duty of blowing a horn to warn neighbouring settlements that the waters were rising – ‘blotton’ being a Saxon word meaning ‘to blow’.

One of Somerset’s major rivers, the Parrett, is tidal as far as Burrowbridge, and used to be navigable (by seagoing vessels) as far as Langport, which disputably boasts England’s first money-lending bank. Visitors to this tiny town are proudly told that, until the 1920s, it was possible to buy a ticket for a berth from there to New York.

As I write, there is a sea change in the draining of the Somerset Levels. Conservationists value these unique wetlands and their ability to support plants found rarely elsewhere, for example sundew and butterwort. The Brue Valley supports a habitat where flora such as bog myrtle are like a floating lens on the bog itself, and need water flowing beneath them. Wind pumps have actually been installed to keep the water levels up, which must be a first for this region! The great crane, not seen here for hundreds of years, has been successfully reintroduced, and opinion is divided as to whether to re-instate the beaver…

Somerset’s coastline includes another unique feature – the Bristol Channel – whose peculiarities give rise to enough stories to form their own book. This stretch of water has the second highest tidal range in the world, with variations in depth of almost 50ft. The speed of its incoming tide continues to prove fatal for many unfortunates, drowned whilst trying to outrun it, or stuck fast in its quaking mudflats and quicksands. Nowadays people water-ski or surf the Severn Bore, the rip tide that causes waves of over 6ft to move upstream at 10mph. Few know that the Severn Sea once flooded most of Somerset, after the only tsunami ever recorded in these islands.

Inland, Glastonbury Tor is justly famous as a spiritual centre for both the old pagan religion and Christianity, and legend tells us that it was the site of the first Christian church. Many believe it to have been a magnet for systems of life and belief from even further afield, as the Glastonbury Zodiac testifies. The twelve signs of the zodiac, in their correct order, together with a thirteenth figure (the Great Dog of Langport, guardian of the Underworld) are so large that they cannot be seen – except from above … Outlined by earthworks, paths, roads, and the boundaries of ancient fields and waterways, the symbols may predate the developing of the landscape along and around their contours.

These Glastonbury Giants – one of the signs is over five miles across – were discovered by Katherine Maltwood in 1927, while she was working on an early Norman-French manuscript, ‘The High History of the Holy Grail’, written in Glastonbury Abbey; she found that the knights’ encounters with beasts and other characters were mirrored by the topography of the area, and the figures it concealed.

Another feature of Somerset is its incomparable native beverage – ‘Zummerzet be where they zoider apples grow’. Some would even say that Somerset folk owe their smooth and rounded accent to this ancient, natural sustenance:

The constant use of this liquor hath been found by long experience to avail much to health and long life, preserving the Drinkers of it in their full strength and vigour even to very old age … eight men who danced a Morris dance, whose age computed together made eight hundred years … were constant cider drinkers.

If the stories in this book inspire the people who live here to appreciate their home even more, I shall be content. And if they prompt others to visit this place where every stone whispers magic, I shall be content.

Sharon Jacksties, 2012

One

THE SALT SEA STRAND

The Bristol Channel

The Bristol Channel is known to be one of the most treacherous stretches of water in Europe. In the great flood of 1607, a huge wave, attributed to a tsunami in the Irish Sea, flooded 200 square miles of land, drowning 3,000 people. Entire villages were washed away, and the flood reached inland as far as Glastonbury.

Many songs refer to the changeable and destructive nature of this channel, which has taken so many lives:

Now Severn she’s wide as the eye can scan

And she wrecks them under both craft and man

Singing farewell shore, ’tis Severn no more

There’s none can ride her mighty bore

When she do rise with a terrible roar

Singing farewell shore, ’tis Severn no more.

Oh Severn do shine and she lies still

And all comes home both safe and well

Singing welcome shore, ’tis Severn no more

Despite the dangers of these waters, they provide a specialist living for those whose courage is supplemented by local knowledge passed down through the generations. Making the most of this tidal landscape, special wooden sledges were used to skim over the mud, in order to set nets and willow-basket salmon traps.

Following the great autumn tides, October is the best season for hunting conger eels. This sport is known as ‘glatting’, and the Severn Sea is the only place where this form of hunting developed. Dogs were trained to sniff out the eels’ lairs beneath the rocks, only revealed at lowest tides. The eels – aggressive and territorial – would be poked with a stick at least 8ft long until they were enticed from their hideaways to attack their tormentor. The dogs would worry them, whilst a blow to the head with a glathook (a hooked iron rod) would finish them off. Eels weighing 30lb and measuring over 6ft were not uncommon, and were a match for any dog. The glatter would have to be fast and skilful to avoid injury to his faithful companion.

Oh ’tis in October days when the mudflat open lays

We do take our prong and our dogs along

And a-glatting we do go so merry

When October tide is low, ’tis then the congers go

We do take our prong and our dogs along

And a-glatting we do go so merry

We do turn the rocks about and the dogs will pull them out

We do take our prong and our dogs along

And a-glatting we do go so merry

Stories of giant eels abound; they were perhaps the origin for many regional tales of water monsters, such as sea serpents and asrais.

Berrow Sands is a notoriously shifting body of sand, just submerged enough to be completely hidden at low water. Whole wrecks have disappeared into its sandy grave, with entire crews sucked under by quicksands. Small wonder, then, that it was considered to be the lair of a sea monster…

THE MONSTER FISH

Not so long ago that we can’t remember, there was a monstrous fish that lived near the Berrow Sands. Its mouth was so big, and it had so many huge teeth, that it could splinter whole boats to get at the crews. It devoured the men, with huge conger eels getting the leftovers. These eels, companions to the monster fish, grew so large that they too were a menace – but not if you were in a boat, only if you fell overboard, and then they would get you, several at a time.

Sometimes, if a boat foundered on those sands, it didn’t matter how loudly the sailors called for help or how many flares they set off, as it was too dangerous for another boat to approach; they couldn’t tell where the sandbank began, and they would get stuck too.

All you could hope for was that the boat wasn’t caught by quicksand, or that the incoming tide would lift it off. Mind you, you also had to hope that you were stuck where the water was too shallow for that monster fish to reach the boat. There are sailors who have seen the fish approach but draw no nearer, because the water wasn’t deep enough. And, just when they thought they might be saved by the rising tide, that fish has started lashing with its tail, shifting the sands to get the boat near enough for its jaws to reach it. Some say that the worst way to die in this place was when the boat was sinking in the quicksand and the giant eels got to you first. There have been men who have witnessed this from their boats, being unable to get quite close enough to rescue the trapped crew.

Those giant eels used to bark. You could hear them from the shore, and it meant that they and the giant fish were hungry, and everyone knew it was an especially dangerous time to be in a boat.

Well, there was once a very brave fisherman who heard the barking one moonlit night. He set out for the sands all by himself, knowing that it would be too risky to take anyone with him. Sure enough, in the moonlight he could see those eels raising their heads above the water and barking, and then diving down and nudging the boat from beneath. He could have sworn they were pushing it towards the monster fish, because suddenly there it was, right in front of him, with its huge mouth as big as a cave. It could easily have swallowed the boat whole. The fisherman bided his time until it got close enough, then he took up the anchor chain and he flung that anchor with all his might. It landed in the monster’s maw like some giant fish hook, and clean finished him off. Some say it was the cold iron and not the hook that did for him. That fish was never seen again, nor those eels heard to bark.

The Severn coast has its own name for mermaids – sea morgans, who are said to come ashore in St Audries Bay, at the foot of the waterfall which cascades to the beach. Local people call the razor shells found there ‘sea morgans’ combs’.

THE SEA MORGAN’S CHILD

There was once an old couple living not far from St Audries. One night the man, who was a fisherman amongst other things, went down towards the beach – but as the tides weren’t right for fishing, he must have been about his other business.

It was a calm night, so he could clearly hear singing above the sighing of the surf. It was the most beautiful sound he had ever heard and he yearned to get nearer. Silently he crept closer, until he could plainly see a group of sea morgans on the rocks below the waterfall. Some were dipping in and out of the rock pools, some were combing their long hair with razor shells, and all were singing.

He was so entranced that he stayed listening to them, without noticing that his body had gone stiff with cold. When at last he tried to change his cramped position, he stumbled and alarmed the sea morgans, who had never been so close to a human on the land. In their rush for the water, they left behind one of their children. She was so young that she had not yet started to grow her tail, and she waved her fists and gurgled up at him. The fisherman thought of his own child, who had been buried before she could walk. He scooped up the sea morgan and took her home, where he and his wife doted on her.

If neighbours wondered where she had come from they said nothing, but there was some comment when the couple named her Morgan.

‘As though there lacked wholesome Christian names to choose from, and they has to go and choose that heathen-sounding name,’ said one of the gossips.

Morgan grew as all children – except that she was overly fond of water and never seemed to feel the cold. She was always paddling through puddles and splashing in streams, and couldn’t even pass a bird bath without dabbling and flicking the water. She never seemed to notice if her clothes were sopping wet, whilst her adoptive mother always complained that she could never get her hair dry. But, when she started to sing, the air was filled with such sweetness that no one could stay cross with her; everyone smiled, forgetting her curious ways and their own troubles.

Because of her voice she was wanted in the church choir, but Morgan could never stay in church for long and always slipped away as soon as the service started. One Sunday, the emerging congregation heard splashing and singing, and found her swimming in the millpond. This was too much for the village busybodies, who marched round to her parents’ house to complain.

‘A gurt girl like that making such a heathen-showing of herself, when she should be at worship like every Christian soul …’ The gossips were trying to bustle into the cottage, whilst the old couple tried to hustle Morgan outside.

‘… And if her hair isn’t wringing wet still …’

Suddenly Morgan cried out, ‘What’s that singing? I know that song!’

Everyone could hear the most unearthly sweet sound coming from the direction of the sea, and the old man too recognised the song – but pretended he couldn’t hear it.

‘They are calling me now – there’ll be a storm tonight – they are calling me with my own song!’ And she was gone, running towards the shore.

The busybodies scuttled off to fetch the priest to chase the witch away – but they needn’t have bothered, because Morgan was with her own kind as they dived and swam and sang, and that’s where she wanted to stay.

And that night the storm was beyond imagining!

Breakers go crashing to foam as they go

There’s laughter and shouting far down below

The ripples they go running all on the incoming tide

Whisper of laughter from side to side

But no one goes looking whoever they may be

No one goes seeking the folk of the sea

The waves all awash on the bars of the beach

Murmur of sorrow, murmur of grief

Now seamen set sail; there’s green hair afloat

And eyes under water follow the boat

But no one goes looking whoever they may be

No one goes seeking the folk of the sea

Not all sea morgans were as harmless. One of their loveliest was never seen near the shore, but was heard and seen out to sea. Some say that she fell in love with a sailor and was abandoned by him, and that she had sworn revenge on all of his kind ever since. On moonlit nights, seafarers would hear her singing, and some would even change course to keep that sound with them. Sometimes they were allowed glimpses of her beauty … as she lured them to the lair of a giant eel, who would overturn their boat and devour them.

The sea is the womb

That cradles the grave

That rocks the tomb

That births the wave

That smoothes the bed

That lays the dead

BIG BLUE BEN

Big Ben was a huge dragon who lived inland before he became blue. His huge size was matched by his ferocity and he spouted massive quantities of fire. These attributes were coveted by the Devil, who, consumed with envy, wanted Ben for himself – rather like the ‘must have’ chihuahua that matches a fashion junkie’s handbag.