0,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Quickie Classics

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

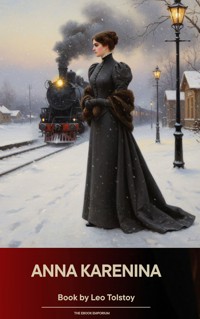

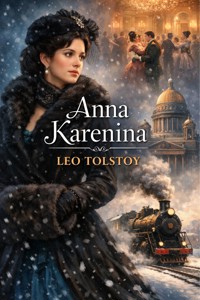

First serialized in The Russian Messenger (1875-77), Anna Karenina entwines Anna's fatal affair with Vronsky and Levin's countervailing search for ethical life, opposing metropolitan spectacle to agrarian labor in post-Emancipation Russia. With omniscient, psychologically exact realism and free indirect discourse, Tolstoy anatomizes marriage, faith, and status; railways, salons, courts, and fields become motifs through which modernity unsettles inherited codes. An aristocratic landowner at Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy drew on diaries, peasant schooling experiments, and stern self-scrutiny. Disillusionment with Petersburg society and the law, together with a marriage that sharpened his interest in family ethics, inform Levin's quasi-autobiographical arc, while the novel's juridical scenes, ecclesial debates, and railway sublime echo his Crimean War memories and fascination with industrial change. Rendered in the Annotated Maude Translation, by Aylmer and Louise Maude, Tolstoy's authorized translators, this edition couples lucid, faithful prose with notes on ranks, calendars, idioms, and social ritual, easing Russian names and contexts. It suits students and scholars alike, preserving tonal nuance while clarifying culture. For readers of serious realism, it is essential. Quickie Classics summarizes timeless works with precision, preserving the author's voice and keeping the prose clear, fast, and readable—distilled, never diluted. Enriched Edition extras: Introduction · Synopsis · Historical Context · Author Biography · Brief Analysis · 4 Reflection Q&As · Editorial Footnotes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2026

Ähnliche

Anna Karenina (Summarized Edition)

Table of Contents

Introduction

In Anna Karenina, the conflict between private passion and public duty unfolds amid the glitter and grind of a society in transition, where love promises freedom, marriage demands compromise, reputation polices every gesture, and the accelerating rhythms of modern life press upon fragile hearts until inner conviction, communal judgment, and the search for meaning collide. Across salons and stations, drawing rooms and fields, the fault lines between city glitter and country labor, desire and responsibility, faith and skepticism, privilege and conscience shape lives that seek wholeness yet encounter limits, asking what kind of truth a person can live when the world insists on compromise.

Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is a realist novel set in late nineteenth-century Imperial Russia, moving between St. Petersburg, Moscow, and provincial estates. First serialized in the 1870s and then published in book form soon after, it enters a world shaped by aristocratic rituals, shifting economic realities, and the technologies of a new age. This annotated Maude translation presents a classic English rendering by Louise and Aylmer Maude together with clarifying notes, offering guidance through ranks, customs, and idioms that structure the characters’ lives. The result situates readers within a precise social landscape while preserving Tolstoy’s breadth of vision and psychological exactness.

The novel opens with domestic unease in a prominent family, a disturbance that draws a visiting sister to Moscow and sets several lives into new alignment. As the city’s winter season hums, chance meetings kindle attractions, and the strains of marriage, kinship, and status reveal themselves in small gestures and shifting silences. In parallel, a country landowner navigates work, courtship, and spiritual perplexity, offering a counterpoint of soil, seasons, and conscience to the glitter of the capital. Tolstoy’s omniscient narration moves fluidly among consciousnesses, combining social panorama with intimate interiority in a tone at once compassionate, scrupulous, and unsparingly observant.

At its core, the book examines how love generates both illumination and blindness, and how marriage can be a shelter, a discipline, or a crucible. It probes the ways institutions—family, law, church, press, and estate—shape choices, assigning honor and shame with a force that may outlast private intentions. It studies the friction between urban spectacle and rural labor, asking what forms of work and community can ground a life. Throughout, Tolstoy attends to the moral texture of everyday acts, showing how glances, rumors, debts, and duties accumulate into character, and how the wish to live truthfully clashes with fear, pride, and habit.

For contemporary readers, these tensions feel immediate: the negotiation between personal authenticity and social expectation, the public life of private choices, and the velocity of change that tests inherited norms. The novel’s attention to mental strain, jealousy, and the anxious calculus of reputation anticipates concerns familiar in an age of constant scrutiny. Its meditation on work, purpose, and belonging resonates beyond class or geography, inviting reflection on how people construct meaning amid competing demands. Crucially, Tolstoy’s refusal to reduce characters to types models an ethic of understanding, asking us to read others—and ourselves—charitably, even when the cost of sympathy is discomfort.

The Maude translation, long valued for its balance of accuracy and fluent prose, gives English-language readers a supple equivalent of Tolstoy’s clarity of thought and cadence of scene. Annotations help decipher forms of address, social ranks, calendars, travel practices, and allusions that can otherwise blur into the background, illuminating why a glance matters here, a dinner there, a railway timetable somewhere else. By contextualizing customs and institutions, the notes enrich character motivations without intruding on them, allowing the narrative to breathe while deepening comprehension. The edition thus supports both first-time readers and returning admirers seeking renewed precision and nuance.

Approached patiently, the novel yields a rare fullness: shifting scenes accumulate into a living society, and quiet details gather power until they glow with moral significance. Its chapters invite attention to gesture as much as event, to weather and rooms as much as declarations. The experience is capacious rather than hurried, rewarding reflection on how lives intersect, diverge, and echo. In this annotated Maude edition, clarity of language and contextual insight guide the way without steering it, honoring Tolstoy’s breadth while supporting careful reading. What follows is not a lesson delivered but a world encountered, unsettling in its honesty and grace.

Synopsis

Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, presented here in the Annotated Maude Translation, opens amid a domestic crisis in Moscow. Stepan Oblonsky's infidelity has unsettled his marriage, and his sister Anna travels from St. Petersburg to help restore calm. The novel introduces a crowded social world of kinship ties, official ranks, and drawing-room rituals, where personal failings quickly become public knowledge. The Maude translation's plain style and the edition's notes clarify the period's customs while preserving Tolstoy's expansive realism. From the outset, the narrative establishes its central tensions: loyalty and desire, private conscience and public standing, and the fragile arrangements that hold families together.

While in transit to Moscow, Anna's path crosses that of Count Alexei Vronsky, a fashionable cavalry officer. His presence also shapes the prospects of Kitty Shcherbatskaya, a young debutante courted by Konstantin Levin but dazzled by Vronsky's charm. A ball crystallizes these competing attachments and leaves Kitty disillusioned. Levin, earnest and awkward, withdraws from the capital after a rejected proposal, returning to his country estate to reexamine his aims. The narrative now tracks parallel trajectories: the quickening attraction between Anna and Vronsky, and Levin's uneasy search for an authentic life, setting in motion a study of choice, consequence, and self-knowledge.

Back in St. Petersburg, Anna resumes life with her husband, the punctilious official Alexei Karenin, and their son. The capital's salons, especially those around Princess Betsy Tverskaya, provide a stage for Vronsky's attentions and for subtle negotiations of propriety. Karenin values order and reputation, interpreting marital duty through legal and institutional lenses, while Anna feels an awakening that defies conventions she once upheld. Social observation is central here: the narrative weighs gestures, glances, and rumors to show how reputation is formed and policed. The tension between an inner sense of truth and outward conformity steadily intensifies, drawing each character into difficult choices.

In the countryside, Levin throws himself into estate management, hoping practical labor will yield clarity. He studies agricultural methods, debates cooperation with peasants, and works alongside them in the fields, discovering moments of harmony and limits to reform. His conversations with friends and family circle around faith, science, and moral responsibility, revealing a mind at odds with the era's ambitions and his own restless heart. Tolstoy juxtaposes this rural immersion with urban spectacle, contrasting steady rhythms of work with the volatility of desire. Through Levin, the novel asks how a meaningful life might be built from duty, labor, and honest relation to others.

Society's pleasures and competitions supply both diversion and judgment. A celebrated race day centers attention on Vronsky's daring and the crowd's appetite for drama, while Anna navigates admiration and scrutiny with growing unease. Karenin, attentive to forms and appearances, seeks to manage his household within legal and social codes, even as private emotions complicate every calculation. The narrative registers the ways public events intrude on intimate lives, making even personal choices into spectacles. Throughout, the novel resists melodrama, showing how small decisions, invitations, and glances bind people into patterns that become hard to change once the city begins to talk.

Away from these salons, Kitty's story bends toward recovery. After disappointment, she travels abroad with her family to a health resort, where she meets Varenka, whose steady kindness models a quieter ethic of service. Kitty learns to temper expectation with patience and finds renewed dignity in caretaking and friendship. Meanwhile, Levin's troubled brother Nikolai struggles with poverty and illness in Moscow, accompanied by Marya, whose loyalty confounds social prejudice. Their situation confronts Levin with suffering he cannot systematize. These chapters broaden the novel's moral canvas, asking how compassion operates across class boundaries and how ideals change when faced with bodily fragility.

Levin returns to Moscow, where changed circumstances allow him and Kitty to renew their connection. Their courtship, frank and tentative, leads to a commitment that moves the narrative into domestic spaces: a country household, seasons of work, and the practical negotiations of shared life. Tolstoy attends to letters, silences, and small compromises, tracing how affection is tested by temperament, finances, and expectations. The couple's hopes for children and a stable home bring joy and anxiety in equal measure. In these pages the novel balances its portrait of passionate rupture with one of patient construction, considering what endurance and kindness require day after day.

For Anna and Vronsky, the costs of defying convention accumulate. Social invitations diminish, family ties strain, and legal mechanisms determine access to a child. Seeking freedom, they travel abroad, where new settings briefly ease scrutiny as Vronsky experiments with artistic pursuits and Anna measures happiness against isolation. Returning to Russia renews old pressures, and the relationship's intimacy becomes entangled with jealousy, dependence, and wounded pride. Karenin's stance, oscillating between law and conscience, reveals institutional limits and human ambivalence. Through these developments, the novel studies a society's double standard and the emotional weather of lives lived at odds with their declared values.

By interlacing a story of disruptive passion with one of deliberate domesticity, Anna Karenina assembles a wide inquiry into love, duty, belief, and social order. Its chapters move from salons to fields, from bureaucratic offices to railway platforms, always attentive to how institutions shape private choices. Without resolving every tension, Tolstoy leaves readers examining the costs of honesty, the uses and failures of law, and the search for a sustaining meaning in ordinary life. In the Maude translation, supported by annotations, the novel's breadth and nuance remain clear, securing its reputation as a capacious moral portrait of a society and its contradictions.

Historical Context

Anna Karenina unfolds in Imperial Russia during the 1870s, primarily in St. Petersburg, Moscow, and on landed estates. The reign of Alexander II framed public life, with the Imperial Court, the Orthodox Church, and the civil service organized by the Table of Ranks shaping elite society. French remained the prestige language in salons, while Russian was standard in administration and law. Expanding railways linked capitals and provinces; the St. Petersburg–Moscow line, opened in 1851, symbolized accelerated mobility and modern timekeeping. Within this setting, Tolstoy depicts aristocratic households, government offices, clubs, and country properties, testing traditional honor codes against emerging urban routines and technologies.

The 1860s–1870s were defined by Alexander II’s “Great Reforms.” The 1861 Emancipation abolished serfdom, creating legally free peasants bound to village communes (obshchiny) and burdened with long-term redemption payments. The 1864 zemstvo reform introduced elected local self-government in many provinces, while the judicial reform established independent courts, public trials, and juries. A modernized military followed, with universal conscription in 1874. These institutions reconfigured gentry authority and village life, altered social mobility, and introduced new arenas for civic participation. The novel’s scenes of estate management, provincial meetings, and legal proceedings mirror these structural shifts, stressing their friction with entrenched hierarchies and habits.

After emancipation, many landowners faced shrinking incomes, debts, and the need to adopt efficient farming. Debates raged over the peasant commune’s role versus private landholding, crop rotation, and machinery. Zemstvo statisticians and agricultural societies gathered data, while periodicals publicized model practices and the promise of scientific agriculture. Grain remained central to Russia’s export economy, yet uneven soils, climate, and labor incentives complicated reform. Tolstoy, himself a country squire at Yasnaya Polyana, drew closely on these realities. The novel’s attention to harvests, wages, and local elections reflects national arguments about how to reconcile moral responsibility with profitable, sustainable estate management.

Marriage in the Russian Empire was a sacrament administered by the Orthodox Church, and divorce required ecclesiastical courts, with limited canonical grounds such as adultery, impotence, or penal exile. Legal separation and child custody were likewise church-governed, and social penalties for marital transgression fell particularly on women in high society. Property norms were patriarchal, though dowries and settlements could mitigate dependence. Simultaneously, the “woman question” was widely debated in the press and universities; St. Petersburg’s Bestuzhev Courses opened in 1878 to expand women’s higher education. Against this landscape, the novel scrutinizes reputation, conscience, and the unequal consequences of public scandal.

Russian intellectual life was polarized between Westernizers and Slavophiles, and, by the 1870s, by populist (narodnik) activism that called educated youth to “go to the people.” Censorship was loosened but not abolished by the 1865 Temporary Press Rules, enabling a vibrant periodical culture with political and literary debate. Anna Karenina appeared serially in Mikhail Katkov’s conservative journal The Russian Messenger from 1875 to 1877. Tolstoy’s psychological realism engages contemporary questions—material progress, faith, and reform—without endorsing revolutionary doctrines. The narrative’s measured, critical distance from ideological polemics reflects the journal’s milieu while keeping moral inquiry and everyday ethics at the center.

Foreign affairs colored domestic atmosphere during the decade. Pan-Slav sentiment surged, philanthropic committees gathered aid, and volunteers joined Balkan struggles that culminated in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. Newspapers reported campaigns and diplomatic congresses, notably the Treaty of San Stefano and the Congress of Berlin, shaping drawing-room talk from capitals to provinces. The army’s reorganization and public patriotism coexisted with sober appraisals of cost and competence. Although not a war novel, Anna Karenina includes conversations about service, duty, and Russia’s mission, registering how international crises threaded into private decisions and tested the credibility of official rhetoric and social conformity.

Urban modernity altered rhythm and spectacle. Rail lines multiplied, stations became city gateways, and timetables disciplined work and leisure. The telegraph quickened news circulation, and mass-circulation newspapers fostered common reference points. Public entertainments—opera, skating, races—showcased status and taste, while clubs codified elite sociability. In Moscow and St. Petersburg, new boulevards and apartment living pressed proximity between classes, even as etiquette policed boundaries. Trains and platforms, emblematic of mechanized time and chance, punctuate the book’s world from its opening scene. Tolstoy’s attention to speed, publicity, and crowd psychology registers the promises and hazards of an increasingly synchronized, mediated urban society.

Leo Tolstoy wrote Anna Karenina after War and Peace, combining panoramic social observation with exacting moral scrutiny. His service in the Caucasus and the Crimean War, work in peasant schools, and long experience managing his estate informed his skepticism toward officialdom and his sympathy with ordinary life. The novel preceded his late religious crisis but already probes faith, repentance, and the limits of worldly success. In English, Aylmer and Louise Maude—friends of Tolstoy and authorized translators—produced an influential early twentieth-century version. Annotated editions now situate names, ranks, and customs, clarifying how Tolstoy’s critique emerges from verifiable institutions, reforms, and mores.

Author Biography

Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) was a Russian novelist, essayist, and moral philosopher whose work reshaped the modern realist tradition and broadened literature’s moral horizons. Writing in the turbulent decades of the late imperial period, he combined panoramic social vision with exacting psychological insight. His major novels became touchstones for discussions of history, freedom, and ethical responsibility, while his shorter fiction distilled those concerns into concentrated narratives. Beyond literature, Tolstoy’s public statements on religion, war, and social justice stirred international debate. Across genres, he pursued the question of how to live truthfully, and his authority as an artist and thinker extended well beyond Russia to readers worldwide.

Born at Yasnaya Polyana into the Russian nobility, Tolstoy was educated by tutors before entering Kazan University, where he studied languages and law. He left without a degree and pursued an intensive program of self-education, reading widely in history, philosophy, and European literature. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s moral writings, the Gospels, and classical authors such as Homer influenced his early outlook, as did Russian literary realism emerging around him. Tolstoy kept detailed diaries, cultivating habits of observation that shaped his style. Though not formally affiliated with a school, he absorbed and reshaped the techniques of realism, seeking a truthful representation of consciousness, everyday life, and the ethical demands of action.

In the 1850s Tolstoy served in the Caucasus and during the Crimean War, experiences that informed his first mature works. Sevastopol Sketches offered vivid reports from the siege and established his reputation for unflinching realism. Around the same time he published the autobiographical trilogy Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth, exploring memory and moral formation. He also wrote stories set among peasants and began formulating ideas about education, later producing primers and essays aimed at practical instruction. These early efforts already display Tolstoy’s hallmark blend of documentary precision and philosophical inquiry, foreshadowing the larger canvas on which he would examine history, society, and individual conscience.

Tolstoy reached international prominence with two vast novels. War and Peace, written mainly in the late 1860s, interweaves domestic life with military campaigns, reflecting on causation in history and the limits of power. Anna Karenina, composed in the 1870s, examines love, duty, and social judgment within a changing society. Readers and critics recognized both books as landmarks of realist art for their structural daring, multiplicity of perspectives, and extraordinary attention to lived detail. Tolstoy’s narrative method—shifting focalization, close psychological rendering, and the integration of thought with action—redefined expectations for the novel and contributed decisively to its modern form.

From the late 1870s Tolstoy underwent a profound moral and religious crisis that he recounted in A Confession. He came to advocate a radical ethic grounded in the teachings of Jesus, emphasizing nonviolence, love, and rejection of coercive institutions. Works such as The Kingdom of God Is Within You and What Is Art? argued for moral clarity, simplicity of life, and an art oriented toward ethical truth rather than aestheticism. His critiques brought him into conflict with authorities, and he was formally excommunicated from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1901. His ideas on nonviolent resistance later influenced figures including M. K. Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.

Tolstoy continued to produce major fiction alongside essays and correspondence. The Death of Ivan Ilyich, The Kreutzer Sonata, and Master and Man offered concentrated examinations of mortality, desire, and moral awakening. Resurrection addressed injustice and institutional hypocrisy, while Hadji Murat, published posthumously, returned to the Caucasus to explore honor and imperial conflict. He wrote extensively on education and social welfare and helped organize famine relief in the early 1890s. His public positions against capital punishment and militarism, coupled with his advocacy of nonviolent ethics, made him a prominent—sometimes controversial—moral voice as well as a celebrated artist.

In his final years Tolstoy maintained a demanding schedule of writing and correspondence, increasingly focused on practical ethics and the difficulties of living by his principles. In 1910 he left his home seeking solitude and died shortly afterward at a railway station after falling ill. His legacy is vast: a reimagined novel form capable of encompassing private consciousness and public history; a body of moral and religious thought that continues to inform debates about violence, justice, and responsibility; and an enduring influence across languages, media, and disciplines. Tolstoy remains central to world literature and to ongoing conversations about how art can illuminate life.

Anna Karenina (Summarized Edition)

Leo Tolstoy: A Short Biography

by Aylmer Maude

TOC

Count Leo Tolstoy entered the world on 28 August 1828 in a country house near Tula, south of Moscow. Country air always suited him, and he would later claim people thrive when close to fields and forests instead of crowding cities. He lost his mother at three and his father at nine, sorrows that left early gaps in his heart. At twelve a visiting schoolboy stunned the Tolstoy brothers with the whispered discovery: “There is no God; everything we’re taught is invented.” The seed of doubt sprouted quickly in a boy already keen to watch, question, and oppose accepted opinion.

School days in Moscow entrenched that skepticism. Among educated Russians “religion” already sounded old-fashioned; Tolstoy absorbed the mood before he was grown. At Kazan University he chose Oriental languages but soon abandoned lectures and failed his finals. He later remarked that the sharpest boy often languishes at the bottom, distracted by his own burning questions. Bright thoughts, however, could not compete with fashionable salons in his aunt’s Kazan house, where uniforms, cards, and flirtation lured him nightly. Serious study withered; debts blossomed. Still searching for direction, he quit academia, rode home to Yasnaya Polyana[1], and attempted to uplift the serfs.

He drew up schemes, planted trees, opened huts as schools, yet progress stalled; his own restlessness and card-losses outweighed reform. After three years he escaped to the Caucasus to economise and to follow his beloved elder brother in the army. Wild hills offered hunts, vodka, officers’ jokes, and the lonely night hours in which he drafted first sketches. Eventually he took a commission; Russian forces were wrestling fierce mountain tribes, and Tolstoy tasted both exhilaration and disgust. Whirling sabres, campfire songs, and silent corpses lodged inside him, promising future pages but also debts of conscience still unpaid to settle later.

When Crimea flared in 1854, he requested active duty, travelling first to the Danube frontier, then to the besieged bastion of Sevastopol. His uncle Prince Gorchakov commanded the army and installed him on staff, yet Tolstoy preferred mud-filled trenches where shells shrieked and men cursed. There he saw war naked: rulers quarreling over “Holy Places” and cryptic treaty lines, staying safely at home while conscripts from Lancashire, Picardy, Sardinia, Anatolia, and Russia slaughtered strangers they had never met. Over half a million died, £340,000,000 vanished, and in the end diplomats bargained only about ships allowed on the Black Sea waters.

Fifteen years passed; France fought Germany; Russia quietly tore up the Black Sea clauses, and foreign ministries now declared the old pact irrelevant. Lord Salisbury later admitted Britain had “put our money on the wrong horse,” though voicing such truth during the carnage would have been branded unpatriotic. Everywhere patriotic drums drowned honest words until the blood dried and memory cooled. Tolstoy never forgot how authority erased promises when convenient, then summoned peasants to die for slogans about “oppressed nationalities.” That bitter lesson fermented in him, shaping every later protest against war, coercion, and the lying splendour of empire rhetoric.

Peace restored, he settled in Petersburg amid chandeliers, receptions, and literary ovations. A noble officer fresh from heroic Sevastopol and already acclaimed for vivid sketches, he possessed applause, fortune, and endless invitations. For a year the glitter charmed; in the next it sickened him. He asked, “If my tales are paid so richly and praised so loudly, what vital message do they carry?” Gazing around glittering parlours he heard only clever style without substance, one writer contradicting another, bohemians lauded today, mocked tomorrow. The moral tone seemed lower than the barracks he had left. Disquiet swelled into self-disgust and silence.

Recalling those years he later wrote: “I cannot now think of them without horror, loathing, and heart-ache. I killed men in war, challenged duels, lost at cards, consumed what peasants produced, sentenced them, lived loosely, deceived people… there was no crime I did not commit, yet society approved.” The statement, he confessed, exaggerated details for moral emphasis; nevertheless he had indeed drifted within an immoral upper-class whirlpool, struggling intermittently toward better shores. Judged even harshly, contemporaries still considered him above average, yet his conscience cried louder than their compliments and drove him back to the countryside for clarity and penance.

Near his birthplace he managed estates and experimented with freeing serfs by commuting service into payments; full liberty had to await the 1861 decree, yet his efforts trained him for later battles. He opened village schools, believing that before teaching cultured crowds he must learn what to teach simple children. Soon he realized even that required knowing life’s purpose lest lessons merely help a pupil “get on to other people’s backs.” Two European tours followed; Prussian drill-schools and French classrooms struck him as grinding disparate minds like coffee beans for teachers’ convenience while parents neglected their own offspring at home.

Conflicting aspirations strained body and nerves until prostration loomed. Doctors ordered absolute rest; he journeyed eastward, living among the wild Kirghiz, drinking fermented mare’s milk, riding steppe horses, and letting thought subside to animal rhythm. Strength returned slowly; habits realigned. In 1862 he married Sofya Behrs, a bond sealed by deep affection that outlasted subsequent quarrels about property, poverty, and publication. Thirteen children were born, five lost young. Twenty years of active family life, his wife copying War and Peace seven times, partly muffled the metaphysical roar inside him, yet the unanswered question kept whispering beneath lullabies of nightly care.

As a government-appointed Mediator he travelled district roads settling disputes between former serfs and landlords. Meanwhile, during fourteen fertile years he composed the vast chronicle War and Peace and the tragic Anna Karenina, revising each page relentlessly until satisfied. Sofya’s devoted copying, lamp-lit through winter nights, mirrored his own perfectionism. Yet when guests praised the novels he silently wondered what use grand art was if it left the riddle of existence intact. The bigger his renown, the louder the inward cry. Ultimately the cry crystallised into a single demand: “What is the meaning of my life?” for me to discover.

He examined possible answers systematically. Wealth? He already owned twenty thousand Samara acres and earned lavish royalties; doubling riches would only double dread when death arrived to confiscate all. Family affection? Watching anxious parents ruined by a child’s fever showed him that tying purpose to fragile loves bred terror. Fame? Suppose he outshone Shakespeare; languages change, libraries burn, and he would not be here to enjoy posthumous applause. Each prospect ended beneath the same black archway: death. As dread sharpened, life itself seemed a cruel joke, and the notion of suicide hovered like a cold, tempting blade above his pillow.

Clinging to existence, he questioned those reputed to know. Scientists offered intricate tales of immutable atoms, self-acting evolution, suns cooling, species rising and vanishing; ingenious indeed, yet it answered only “How did I get here?” not “Why am I here?” Priests accepted the question but were shackled by dogma, nailed like insects under printed creeds; they dared not pursue naked truth. Worse, most blessed regiments, sprinkled holy water on ironclads, intoned prayers to confound unnamed enemies, and persecuted rival sects. Disillusioned, he found no help in microscopes or censers; the abyss yawned wider and the pistol drawer remained unlocked tonight.