0,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Quickie Classics

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Spanning 1805–1812, War and Peace follows the Rostovs, Bolkonskys, and Pierre Bezukhov across salons, campaigns, and private reckonings, interlacing intimate realism with sweeping reflections on history and freedom. Tolstoy's shifting focalization, exact psychology, and embedded essays create a capacious, experimental epic. The Maude translation—prepared by Aylmer and Louise Maude in consultation with Tolstoy—renders military dispatches, society chatter, and historiographic argument in lucid, balanced English, from Austerlitz and Borodino to the burning of Moscow. An aristocrat turned moral inquirer, Tolstoy drew on service in the Caucasus and Crimea, broad reading in French and Russian histories, and domestic observation at Yasnaya Polyana. Composed 1865–1869 amid post-emancipation Russia, the novel rejects "great man" legend, recasting history as countless small causes. Through Pierre, Andrei, and Natasha, Tolstoy channels his oscillation between ambition, skepticism, and a quest for ethical simplicity, probing how conscience survives contingency. This Maude edition invites both scholars and first-time readers: the supple prose carries strategic analysis, domestic comedy, and metaphysical inquiry with equal poise. Seek it for a panoramic education in war, love, and responsibility, and for an enduring argument about the limits of power and historical agency. Quickie Classics summarizes timeless works with precision, preserving the author's voice and keeping the prose clear, fast, and readable—distilled, never diluted. Enriched Edition extras: Introduction · Synopsis · Historical Context · Author Biography · Brief Analysis · 4 Reflection Q&As · Editorial Footnotes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2026

Ähnliche

War and Peace (Summarized Edition)

Table of Contents

Introduction

War and Peace traces the perpetual negotiation between private conscience and public convulsion, asking how ordinary lives can seek truth, loyalty, and love while vast, impersonal forces rearrange nations, overturn expectations, and compel people to choose between the urgencies of the heart and demands of history, between the intimacy of home and the clangor of the battlefield, and between the desire to act and the recognition of limits, so that the measure of a life emerges not from isolated heroics or inherited status but from the difficult, evolving integration of feeling, thought, duty, and the stubborn, unpredictable movement of time.

Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, in the Maude translation, is a vast historical novel set in Russia during the Napoleonic era, principally the campaigns that shook Europe in the first decades of the nineteenth century. First appearing in the 1860s, the book unites social comedy, domestic drama, military chronicle, and philosophical reflection into a single, carefully textured narrative. Aylmer and Louise Maude render Tolstoy’s prose into clear, measured English that preserves the novel’s scope and intimacy without ornament. The result is a work that feels at once panoramic and precise, grounded in place and time yet attentive to the smallest fluctuations of feeling.

The story opens among aristocratic salons and family gatherings in St. Petersburg and Moscow, where conversations about war, marriage, and ambition unfold against the distant thunder of European conflict. As the narrative widens, readers follow intersecting households whose decisions are shaped by duty, affection, and the shifting expectations of their world. Campaigns advance and retreat; seasons turn; friendships and rivalries evolve. Battles are observed alongside letters, councils, dinners, and encounters on country estates. Without revealing outcomes, it is enough to say that personal quests for purpose and belonging continually meet the pressures of history, creating a living tapestry of intertwined journeys.

Tolstoy’s narrative voice is lucid and unhastening, moving from the hush of a drawing room to the smoke of a field with the same attentive gaze. Scenes arrive with vivid physical detail, yet the emphasis rests on inner weather—hesitations, impulses, and the moral coloring of choice. The Maude translation underscores this balance, favoring clarity over flourishes and allowing the rhythm of observation to carry the reader forward. The tone is humane rather than judgmental, contemplative rather than rhetorical, and the novel’s pace alternates between intimate episodes and broader panoramas, inviting patience while offering continual moments of recognition.

Central themes emerge with steady resonance: the interplay of individual agency and historical necessity; the porous boundary between war and peace in public and private life; the testing of family bonds; the search for moral integrity; and the question of what constitutes genuine greatness. The book examines power as something dispersed through countless decisions rather than concentrated in a single figure. It weighs chance, habit, and conviction, and it asks what kind of freedom is available within circumstance. Faith, skepticism, and the pull of the everyday coexist, as characters discover that meaning often arises from conduct sustained over time.

For contemporary readers, the novel matters because it resists simplifying stories about leaders and events, modeling a way of seeing that honors complexity without surrendering humanity. In an age of sweeping narratives and accelerated information, War and Peace insists that understanding grows from attention—to motives, contexts, and consequences. It portrays communities under stress, the costs of conflict, and the restorative power of care, work, and friendship. Its portraits of uncertainty feel familiar, and its refusal to sentimentalize suffering makes its compassion convincing. The book encourages humility about prediction and certainty, while affirming that everyday choices still shape the world.

Reading War and Peace in the Maude translation is an immersive, steady undertaking that rewards curiosity and calm persistence. The scale can seem formidable, but the chapters are finely cut, the scenes clear, and the emotional arcs accessible. One can follow the story through households and seasons, noticing how slight shifts in perspective reveal new meanings. The translation’s unshowy diction keeps attention on persons and processes rather than linguistic display. Approached as a living landscape rather than a monument, the novel offers continuous satisfactions, culminating not in a single revelation but in a deep, gathered sense of how lives take form.

Synopsis

Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, presented here as known through the Maude translation, unfolds across Russian high society and the battlefields of the Napoleonic era. Beginning in 1805, it follows interconnected families—the Bolkonskys, Rostovs, and Kuragins—while tracking the fortunes of Pierre Bezukhov, Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, Natasha and Nikolai Rostov, and Princess Marya. Salons in St. Petersburg and Moscow frame debates about duty, honor, and the allure of Europe as Napoleon advances. Private hopes collide with public upheaval, and the novel’s broad canvas alternates between intimate scenes and panoramic historical set pieces, establishing a study of character, chance, and the pressures of history.

In 1805 the young men enter service with differing expectations. Andrei seeks purpose beyond court life and joins General Kutuzov’s staff, while Nikolai Rostov enlists with romantic zeal. Pierre, unexpectedly wealthy after an inheritance, is drawn into Petersburg circles that prize image over conviction, and his impulsiveness leads to a compromising marriage and strained friendships. The campaign culminates in a major defeat for the coalition against Napoleon, and Tolstoy’s depiction of command and confusion challenges heroic myths. Andrei’s encounters in battle and recovery deepen his skepticism about glory, turning his attention toward inner reform and the possibility of a quieter, more principled life.

Between campaigns, the narrative shifts to estates and drawing rooms. At Bald Hills, the austere old prince imposes discipline on his household, shaping Princess Marya’s inward, devout character. In Moscow, the warm but imprudent Rostovs face financial pressures as Natasha blossoms into a charismatic presence. Pierre searches for moral orientation and joins the Freemasons, hoping to improve his conduct and manage his lands justly. Social rituals broker alliances and expectations: Andrei and Natasha are drawn together, while the scheming Kuragins maneuver within fashionable society. Tolstoy contrasts the sincerity of domestic feeling with the performative codes of rank, money, and imperial ambition.

Military life continues for Nikolai, who meets the prosaic hardships of campaigning rather than the triumphs he imagined. Gambling and bravado complicate his friendships, and he struggles to reconcile loyalty to his family with the temptations of regiment life. Pierre’s reforming zeal collides with inertia on his estates, exposing limits to benevolence from above. Princess Marya, isolated by her father’s severity and her own shyness, faces awkward negotiations over marriage and inheritance. Throughout, Tolstoy develops a counterpoint between idealistic resolve and the stubborn particularity of circumstance, suggesting that moral growth emerges unevenly from errors, obligations, and the patient work of everyday duties.

As Europe’s political crisis intensifies, Russia prepares for renewed conflict. Napoleon’s renewed campaign pressures borders and court reputations alike, and strategic debates reawaken old rivalries. Andrei returns to service with a graver sense of responsibility. Natasha’s entrance into society exposes her to admiration and peril; an ill-judged infatuation derails plans and tests her conscience, reshaping her understanding of trust and family. Pierre, restless and self-critical, explores schemes of self-improvement and contemplates decisive action against tyranny, without clarity of means. The novel’s attention to private missteps and reconciliations mirrors the state’s uncertain maneuvers as armies assemble and the nation braces for invasion.

The 1812 campaign brings the war to Russian soil. Tolstoy renders marches, councils, and supply lines alongside the feelings of common soldiers and civilians. Pierre, an observer at a decisive battle, experiences the battlefield’s chaos firsthand, while Andrei confronts command and the cost of courage. Moscow’s evacuation reveals civic improvisation and class tensions; the Rostovs’ hurried departure includes acts of mercy that strain their resources. The city’s occupation and fire alter the social landscape. On country estates, Marya confronts unrest and new responsibilities, finding unexpected support. Through shifting perspectives, Tolstoy questions whether strategy or circumstance governs outcomes when nations are in extremis.

With the French in Moscow, resistance assumes dispersed forms. Partisan bands harry supply lines, and irregular fighters shadow the retreat. Pierre, swept up by events, endures arrest and captivity, encountering ordinary prisoners and soldiers whose resilience reframes his moral search. The peasant Platon Karataev, among others, embodies an unassuming endurance that contrasts with grandiose plans. Kutuzov emphasizes preservation over dramatic victory, a patience that reflects Tolstoy’s skepticism about command genius. As winter deepens and the invaders withdraw, the narrative dwells on small acts of compassion and cruelty, implying that history’s turning points are composed of countless minor choices and necessities.

In the aftermath, armies move west and Russian society confronts losses, debts, and altered expectations. Estates are repaired, households reconfigured, and youthful certainties reconsidered. Pierre returns from adversity changed in temper and aim. Natasha’s earlier innocence gives way to steadier devotion, while Princess Marya and Nikolai negotiate obligations to land, family, and country. Friendships realign as characters seek purposes that fit diminished illusions. Tolstoy allows intimate scenes of reconciliation, responsibility, and shared labor to counterbalance the lingering spectacle of war, suggesting that continuity is rebuilt not by proclamations but by modest commitments that dignify ordinary time.

Alongside the story, Tolstoy threads reflections on causation in history, challenging theories that credit outcomes to singular leaders. He depicts events as the product of innumerable wills and constraints, where choice and necessity interweave. The novel proposes that moral insight arises less from abstraction than from attention to daily life, mercy, and truthful self-knowledge. Its enduring significance lies in uniting a vast historical panorama with the evolution of private character, inviting readers to consider how individuals act within forces they cannot command. The Maude translation conveys this sweep and intimacy, preserving a work that still questions glory and locates meaning in the ordinary.

Historical Context

War and Peace is set in the Russian Empire during the first two decades of the nineteenth century, chiefly in St. Petersburg and Moscow, under the reign of Emperor Alexander I (1801–1825). The state was an autocracy supported by the nobility and a sprawling bureaucracy structured by Peter the Great’s Table of Ranks. Society rested on serfdom, with millions of peasants bound to noble estates, and wealth concentrated in landholdings and court service. The aristocracy spoke French in salons and drawing rooms, read Enlightenment authors, and followed European fashions, while Orthodox rituals, imperial ceremonies, and military service framed elite life and public institutions.

Russia’s place in the Napoleonic Wars defined the external pressures shaping the era. In 1805, as part of the Third Coalition with Austria and Britain, Russian armies met Napoleon and suffered defeat at Austerlitz. After further campaigning, Russia was beaten at Friedland and concluded the Treaties of Tilsit (1807), entering an uneasy Franco-Russian alliance and the Continental System against Britain. Strategic and economic frictions persisted, including disputes over Poland’s Duchy of Warsaw and Russia’s curtailment of the blockade. By 1810–1812, relations deteriorated sharply, setting the stage for renewed conflict that entwined high diplomacy, commercial policy, and dynastic prestige with national survival.

The 1812 campaign was decisive for Russia and Europe. Napoleon’s Grande Armée crossed the Niemen River in June, advancing through Lithuania and Belarus as Russian commanders Michael Barclay de Tolly and Prince Peter Bagration adopted a strategic retreat to preserve forces. Major engagements at Smolensk and the bloody battle of Borodino in September caused enormous casualties. Moscow, largely evacuated, was occupied by the French and then devastated by a vast fire during the occupation. With supplies dwindling and winter approaching, Napoleon withdrew. Russian forces, Cossacks, and partisans harried the retreat, and the crossing of the Berezina further shattered the invaders.

Military institutions and social obligations underpin the conflict’s realities. The imperial army relied on recruit levies, with quotas imposed on communities to furnish conscripts for life or long terms, while the officer corps was dominated by nobles. Elite Guards units stood alongside line regiments, artillery, and engineers. Irregular forces, including Don and other Cossack hosts, excelled in reconnaissance and raids. In 1812 the government mobilized provincial militias (opolchenie) and requisitioned supplies on a vast scale. Chronic shortages of fodder, transport, and clothing shaped operations as much as battlefield plans, and guerrilla actions by figures like Denis Davydov disrupted French logistics.

Russian high society and provincial life were structured by estate culture. Noble households oversaw serf labor, collected dues (obrok) or demanded labor obligations (barshchina), and maintained patronage ties with peasants and dependents. Education for aristocratic children commonly involved foreign tutors, and French remained the prestige language in conversation and correspondence. The Orthodox Church shaped calendars, rites, and charitable activity, while patriarchal norms governed marriage, inheritance, and domestic authority. Freemasonry, popular among some nobles in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, offered moral and philanthropic programs before imperial restrictions curtailed lodges; its language of self-improvement resonated in elite circles.

Administrative reform and conservative reaction marked Alexander I’s reign. Early measures created ministries (1802) and, under Mikhail Speransky, proposed a State Council (established 1810) and constitutional reordering that stalled amid opposition and war. After 1812, the empire assumed a leading role in defeating Napoleon and shaping the postwar settlement, including the Holy Alliance (1815). The presence of Russian troops in Paris and exposure to European politics fostered reformist ideas among some officers, currents that later contributed to the Decembrist uprising of 1825. Though outside the novel’s timeframe, these tendencies grew from the very milieu and campaigns the narrative depicts.

War and Peace engages nineteenth-century debates about historical causation and leadership. Against hero-centered narratives popular in Europe, Tolstoy emphasizes contingency, material conditions, and the collective actions of armies and civilian populations. His depictions of councils, confusion, and logistical limits question the efficacy of grand strategies and the idea that commanders singlehandedly direct events. The portrayal of Marshal Kutuzov’s patience and restraint echoes strands of Russian historiography that credited endurance over decisive maneuvers in 1812. These reflections echo contemporary historiography and moral inquiry, inviting readers to scrutinize patriotic mythmaking, the costs of war, and the limits of individual will within vast institutions.

Composed between 1865 and 1869 and first published in the journal The Russian Messenger, the novel arose amid Russia’s reform era following the Emancipation of the Serfs (1861) and debates over national identity, faith, and social responsibility. Tolstoy drew on histories, memoirs, and official documents to anchor events. The Maude translation, produced by Aylmer and Louise Maude in the early 1920s, reflected their close association with Tolstoy and aimed at linguistic fidelity, including the treatment of French passages. Through its panoramic structure, the work interrogates aristocratic privilege, bureaucratic inertia, and militarized glory, offering a critical mirror to Russia’s past and present.

Author Biography

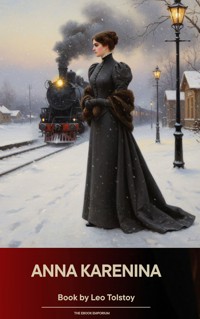

Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) was a Russian novelist, short-story writer, dramatist, and moral philosopher whose work helped define nineteenth-century realism. Writing from the milieu of the late imperial era, he combined panoramic social vision with exacting psychological insight, creating narratives that interrogate power, conscience, faith, and everyday life. His vast novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina are widely regarded as landmarks of world literature, and his later essays on ethics and nonviolence gave him a global voice beyond fiction. Across genres, Tolstoy pursued clarity of moral perception and the dignity of ordinary experience, shaping debates about the novel’s purpose and the demands of ethical living.

Raised on the family estate at Yasnaya Polyana in the Tula province, Tolstoy received a private education before enrolling at Kazan University, where he studied languages and law. He left without taking a degree and began an intensive self-education, reading widely in history, philosophy, and literature. Travels in Western Europe in the late 1850s exposed him to new pedagogical theories and to state violence—most memorably a public execution in Paris—which reinforced his skepticism toward coercive institutions. He founded an experimental school for peasant children at Yasnaya Polyana and wrote about education, advocating freedom in learning. Influences included classical epic, the Gospels, Rousseau, and strands of European and Russian realism.

In 1851 Tolstoy joined the army in the Caucasus, later serving as an artillery officer during the Crimean War. The experience supplied material for his early prose, notably Sevastopol Sketches, a series that rejects heroic clichés in favor of the soldier’s perspective and moral ambiguity. He also published the autobiographical trilogy Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth, and the novella The Cossacks, each refining his interest in self-scrutiny and the tensions between culture and nature. These works established his reputation in Russia as a distinctive realist, attentive to the textures of daily life and to the ethical implications of choice, habit, and social pressure.

During the 1860s and 1870s Tolstoy produced his two major novels. War and Peace, completed in 1869, fuses family chronicle with meditations on history and free will, employing multiple registers—from battle narrative to philosophical essay. Anna Karenina, serialized in the mid-1870s, offers a profound social panorama of urban and rural life, setting intimate stories against questions of duty, desire, and belief. Both books were acclaimed for structural daring, lifelike characterization, and breadth of vision, and they consolidated Tolstoy’s stature as one of the era’s most searching literary minds. Translations soon extended his audience beyond Russia and made his name internationally synonymous with the novel.

After the triumphs of his long novels, Tolstoy underwent a profound spiritual crisis in the late 1870s, described in A Confession. He turned to a radical reading of the Gospels, advocating nonviolence, conscientious resistance to state compulsion, and a simplified way of life. Works such as What Then Must We Do?, The Kingdom of God Is Within You, and What Is Art? critique economic injustice, military service, and aesthetic elitism while proposing an ethics grounded in love and truthfulness. His religious critiques led the Holy Synod to excommunicate him in 1901. Nonetheless, his moral writings influenced pacifist movements and helped shape discourse on civil disobedience.

Even as he advanced his ethical program, Tolstoy continued to write fiction of concentrated power. The Death of Ivan Ilyich examines mortality and self-deception; The Kreutzer Sonata probes jealousy, law, and sexuality; Master and Man explores risk and responsibility amid a snowstorm. His final long novel, Resurrection, challenged legal and penal systems and encountered censorship; he directed proceeds from some later works to support humanitarian causes, including aid to persecuted religious minorities such as the Doukhobors. Posthumously published works like Hadji Murad and Father Sergius reaffirm his interest in courage, hypocrisy, and spiritual testing, demonstrating that his artistic vitality endured alongside his polemical commitments.

In his later years Tolstoy lived mainly at Yasnaya Polyana, writing essays, letters, and educational materials, including primers for children. He sought personal consistency with his moral views while remaining engaged with readers, educators, and reformers in Russia and abroad. In 1910 he left home on a final journey and died shortly afterward at a railway station in Astapovo. His legacy spans art and ethics: a transforming influence on the modern novel’s psychological reach and social scale, and a catalyst for nonviolent thought that inspired figures such as Mohandas K. Gandhi. Tolstoy remains central to global literary culture, frequently read, debated, and adapted.

War and Peace (Summarized Edition)

BOOK ONE: 1805

“Well, Prince, Genoa and Lucca are now just Buonaparte family estates; if you won’t call this war I drop our friendship! But how are you? Sit down and tell me everything.” In July 1805 invalid Anna Pavlovna Scherer, claiming la grippe[1], greets Prince Vasili Kuragin at her fashionable salon. Morning invitations had promised an evening “with a poor invalid.” Unruffled, the decorated courtier bows, kisses her hand, and in polished French asks after her health. “Can one be well when suffering morally?” she sighs. He must later attend the English ambassador’s fête, yet she complains fireworks have become wearisome.

Conversation turns to politics. Prince Vasili murmurs that Bonaparte has burned his boats; Anna Pavlovna suddenly flames: “Oh, don’t speak to me of Austria! Russia alone must save Europe. Our gracious sovereign will crush the hydra of revolution, this murderer and villain! England trades, Prussia schemes, only God and our Emperor remain.” She breaks off, smiling at her own ardor. “If you had gone instead of Wintzingerode you’d have stormed the Prussian king’s consent,” he laughs, requesting tea. She announces the coming of the Vicomte de Mortemart and the Abbe Morio. With studied carelessness he asks whether the Dowager Empress favors Baron Funke for Vienna.

Her lids lower in reverence: “Baron Funke has been recommended by Her Majesty’s sister.” The prince shrugs, so she turns to his household. “Since your daughter came out everyone adores her; but Anatole displeases me.” He sighs that he lacks the bump of paternity, calls Hippolyte a fool and Anatole an active one, and admits his children are the bane of his life. She asks if he has considered marrying the prodigal. Cousin Princess Mary is rich. Vasili tallies the dowry, moans that Anatole already costs forty thousand a year, and clasps her hand: “Arrange it and I am your slave—slave with an f.

And with familiar ease he lifted the maid-of-honor’s hand, kissed it, swung it, then gazed elsewhere. "Attendez," Anna Pavlovna said, "this evening I’ll speak to Lise, young Bolkonski’s wife; on your family’s behalf I begin my apprenticeship as old maid." Her drawing room filled with Petersburg’s elite: radiant Helene in ball dress fetching Prince Vasili, pregnant Princess Bolkonskaya, Hippolyte with Vicomte Mortemart, the Abbe Morio, many more. For every arrival Anna asked, "Have you seen my aunt?" and solemnly led them to the little lady with enormous ribboned cap. Each guest dutifully inquired after Her Majesty’s health, escaped with relief, and never returned.

The little princess placed her workbag by the samovar. "I’ve brought my embroidery; Annette, you promised a small party—look how badly I’m dressed!" Anna smiled, "Soyez tranquille, Lise, you’re always prettiest." She told a general, "My husband deserts me to be killed—what is this wretched war for?" Prince Vasili murmured, "Delightful woman." Pierre Bezukhov, bespectacled, entered. Anna, uneasy, steered him to the aunt; he bowed to Lise, then left the aunt before her speech ended. She intercepted him: "Do you know the Abbe Morio? A most interesting man." "His perpetual-peace plan is clever but impossible," Pierre began, until she said, "We’ll talk later," and fled.

Conversation whirred like spindles. Save the ignored aunt and one wan companion, all settled into three knots: men round the Abbe, youths round Helene and the pink little princess, and a circle round Vicomte Mortemart with Anna Pavlovna. The vicomte—polished, sure of fame yet courteous—was served as the evening’s delicacy. They discussed the murder of the Duc d’Enghien[2]; he said the duke fell by his own magnanimity and Bonaparte’s hatred. "Ah yes, contez-nous cela, Vicomte," Anna cried, savoring the Louis-XV ring. She shifted chairs, murmured, "He knew the duc… finest society," then called, "Come here, Helene, dear," to place the beauty in front.

The princess smiled. She rose with the same serene glow that had marked her entrance, white gown whispering with moss and ivy, diamonds flashing on glossy hair and bare shoulders. She glided between admiring men without looking at them, yet granting each her unchanging radiance, as though a ballroom aura followed her toward Anna Pavlovna. Too lovely for coquetry, she almost seemed shy of her triumphant beauty. “How lovely!” murmured all; the vicomte shrugged, dazzled. “Madame, I doubt my ability before such an audience,” he bowed. She leaned her round arm on a table, waited, adjusted chain and folds, still smiling.

While the vicomte began, Helene sat upright, studied the curve of her arm, shifted a diamond on her bosom, mirrored Anna Pavlovna’s expressions, then relapsed into brilliance. The little princess tripped up, chirping, “Wait, I’ll get my work… Fetch my workbag!” Hippolyte complied and dropped beside Helene; strikingly like his sister, he was nonetheless thin, awkward, and oddly smug. He fixed a lorgnette. “It’s not going to be a ghost story?” “Why no, my dear fellow.” “Because I hate ghost stories,” he declared, baffling all. The vicomte resumed; his neat tale set the Duc d’Enghien and Bonaparte before Mademoiselle George. The ladies gasped, enchanted.

Anna Pavlovna noticed Pierre arguing balance of power with the abbe. “Russia, disinterested, could save Europe!” the Italian proclaimed; Pierre asked how, but she interrupted with talk of climate and swept both men into the salon. Prince Andrew Bolkonski arrived, handsome, bored, cold to his sparkling wife. “You go to war?” “Kutuzov takes me as aide-de-camp.” “And Lise?” “She will stay in the country.” She fluttered about the vicomte’s tale; Andrew turned aside. Pierre gripped his arm. “I’ll sup with you.” “Impossible!” Andrew laughed softly. As Prince Vasili left with radiant Helene, Pierre watched, rapt, and Princess Drubetskaya begged Vasili for her son.

“Listen to me, Prince,” Anna Mikhaylovna whispered, eyes shining. “I have never begged you, but for God’s sake help my Boris, and I shall call you my benefactor.” She fights back tears while Princess Hélène, waiting at the doorway, softly warns, “Papa, we shall be late.” Prince Vasíli, weighing the cost of favors, recalls the debt he owed her father and the obstinacy of mothers like her. At last he sighs, “My dear Anna Mikhaylovna, it is nearly impossible, yet to show my devotion I will do the impossible—your son shall be transferred to the Guards. Are you satisfied

“My dear benefactor, I knew your kindness!” she cries, seizing his hand, then halts him with a final plea. “When he joins the Guards you, who are friendly with Kutúzov, must recommend Boris as adjutant. Then my heart will rest.” Vasíli only smiles. “I will not promise that; Kutúzov is besieged for adjutancies.” “Promise! I won’t let you go!” she insists. Again Hélène murmurs, “Papa, we shall be late.” “Well, au revoir, good-bye; you hear her,” he laughs, adding, “Tomorrow I’ll speak to the Emperor; about Kutúzov I don’t promise.” She pursues him coquettishly; he departs, and her practiced smile stiffens.

Back among the guests, Anna Pavlovna exclaims, “And what do you think of that latest comedy, the coronation at Milan, Buonaparte on a throne granting petitions? The world has gone mad!” Prince Andrei meets her gaze and quotes in Italian, “‘God gave it to me; let him beware who touches it.’” She predicts the sovereigns’ patience will snap; the vicomte retorts that those sovereigns did nothing for the Bourbons and now court the usurper. Hippolyte, peering through a lorgnette, sketches the Condé arms for the little princess. The vicomte warns that if Bonaparte rules another year, good French society will be destroyed.

Pierre, blushing yet eager, bursts out, “The execution of the Duc d’Enghien was a political necessity, and Napoleon showed greatness of soul in assuming full responsibility.” “Mon Dieu!” gasps Anna Pavlovna; the little princess smiles, “Do you call assassination noble?” Cries of “Oh! Capital!” rise, but Pierre presses on: Napoleon quelled anarchy, preserved equality, freedom, a grand achievement of the Revolution. The vicomte scoffs at “liberty and equality,” calls 18th Brumaire[3] a swindle; Anna Pavlovna cites the innocent duc, the princess recalls the African prisoners; Hippolyte mutters, “Low fellow.” Pierre’s kindly, childlike smile disarms them, and at last everyone falls silent.

“How do you expect him to answer at once?” Prince Andrew asks, distinguishing Napoleon’s roles. Pierre agrees. Andrew praises Napoleon at Arcola and Jaffa yet admits other acts defy defense, then signals his wife to leave. Prince Hippolyte leaps up, begs silence, and in halting Russian begins his Moscow anecdote: a miserly lady orders her huge maid, “Girl, put on livery, ride behind the carriage.” Wind blows, the maid’s hat flies off, hair tumbles, “and the whole world knew…!” He collapses laughing; polite smiles follow. Conversation drifts to past and future balls, theater dates, chance meetings.

Guests thank Anna Pavlovna and prepare to depart. Awkward Pierre grabs the general’s three-cornered hat, restores it, and receives her gentle reproof: “I hope to see you again—and that you’ll change your opinions, dear Monsieur Pierre.” He bows, smiling vaguely. In the hall, Princess Lise chats with Hippolyte; Anna Pavlovna whispers about marrying Anatole to her sister-in-law. Hippolyte praises the evening, wraps Lise’s shawl, and keeps an arm round her until she slips away, glancing at her weary husband. “Allow me, sir,” Andrew says coldly when Hippolyte blocks him. The carriage rolls off; Hippolyte, laughing, escorts the vicomte home.

Inside Hippolyte’s carriage the vicomte kisses his fingertips: “Your little princess is charming, quite French. I pity that small officer who apes a monarch.” Hippolyte splutters, boasting of his skill with Russian ladies. Pierre arrives first at Andrew’s house, stretches on the sofa, opens Caesar’s Commentaries. Andrew enters, chides, rubs his hands. Pierre waves: the abbé interests him, peace is possible. Andrew cuts him short, urges him to choose Guards or diplomacy; Pierre hesitates, condemns war against “the greatest man in the world.” Andrew replies, “If men fought only on conviction, there’d be no wars.” A dress rustles; Princess Lise bustles in.

“Why can’t men live without wars?” the princess cries, praising her husband’s post and dreaming of him as the Emperor’s aide. Pierre, seeing Andrew’s dislike, stays silent. “Oh, don’t mention his going!” she pleads, shivering with fear. Andrew, cool and remote, asks, “What are you afraid of, Lise?” She protests: “Men are egotists; you lock me in the country.” He reminds her, “With my father and sister.” Her lip trembles; he orders, “Your doctor says you must rest.” Tears burst. “Why have you changed? You’re going to war and pity me none!” Andrew’s “Lise!” breaks her; she whispers “Mon Dieu,” kisses his brow, and withdraws.

After she leaves, the two men sit wordless until Andrew sighs, “Let’s have supper,” and leads Pierre into the fresh, glittering dining room. Halfway through the meal he drops his elbows on the table; agitation flashes in the face usually so detached. “Never, never marry, my friend! Marry only when you are old or have stopped loving; otherwise you ruin yourself. You’ll be chained to drawing rooms beside lackeys and fools.” He laughs bitterly. “My wife is excellent, yet I’d give anything to be free. Women—selfish, vain, trivial—suck a man into gossip, balls, vanity. Don’t marry, don’t marry

Pierre removes his spectacles and stares, astonished. “You call your life spoiled, yet everything lies ahead.” Andrew shakes his head. “My part is played out. Let’s talk of you.” Pierre smiles shyly. “What am I? An illegitimate son without name or money… I’ve no idea what to do and hoped you’d advise me.” Andrew’s affectionate gaze still hints at superiority. “You’re the one live man among us; choose any path and you’ll succeed. Only quit the Kuragin house—debauchery and ‘women and wine’ don’t suit you.” Pierre shrugs. “Women, my dear fellow!” “Women comme il faut are different,” Andrew replies; “the Kuragins’ are incomprehensible.

“Do you know,” Pierre suddenly exclaimed, “I’ve long been pondering… Leading such a life I can’t decide anything. One’s head aches and one spends all one’s money. He asked me for tonight, but I won’t go.” “You give me your word of honor not to go?” “On my honor!” After one o’clock he left his friend. The pale northern night felt like dawn, too bright for sleep. Near his own door he recalled Anatole’s card party and the wild finale he loved. His pledge to Prince Andrew seemed trivial; “tomorrow one may be dead!” he thought, and turned the cab toward Kuragin’s glowing, drunken house.

Inside, empty bottles, cloaks, and a footman drinking leftovers littered the rooms; laughter, a bear’s growl, and bets echoed. Eight or nine young men crowded an open window while three teased the chained cub. “I bet a hundred on Stevens!” “Mind, no holding on!” “I bet on Dolokhov!” Shirt open and coatless, Anatole hailed Pierre: “Petya! First you drink!” Glass after glass vanished. Amid the din he explained Dolokhov had wagered he could drain a bottle of rum while sitting outside the third-floor ledge, legs dangling. “At one draught, or he loses!” someone cried. Dolokhov ordered the frame removed; Pierre ripped it free.

Dolokhov climbed through the opening, settled on the sloping stone, and set the rum within reach. Anatole placed candles beside him though dawn already glimmered. A guest lunged forward: “I say, this is folly! He’ll be killed.” Anatole restrained him. Dolokhov warned, “If anyone meddles, I’ll throw him down. Now then!” He lifted the bottle, head tilting farther, free hand spread for balance; silence choked the room. Seconds stretched until his body slid, wavered—and steadied. At last he stood upright on the sill, triumphant. “It’s empty.” The bottle flew to the Englishman, coins rattled into Dolokhov’s palm, and Pierre leaped onto the window ledge.

‘Gentlemen, who’ll bet with me? I’ll do it anyway!’ Pierre suddenly shouts, demanding a bottle. Dolokhov grins: ‘Let him do it.’ Friends protest, ‘You’ll get dizzy on a staircase!’ Pierre slams the table: ‘I’ll drink it! Rum!’ He strides toward the window; restraining hands fly, but he sends them spinning with his strength. Anatole laughs, ‘You’ll never hold him. Tomorrow I’ll take the bet—tonight we’re all going to ——’s.’ ‘Come on!’ Pierre roars. ‘And we’ll take Bruin!’ He scoops up the bear, swings it onto his chest, and waltzes round the room, roaring, drunk and invincible.

Prince Vasili keeps his promise to Anna Mikhaylovna: the Emperor approves, and Boris becomes a cornet in the Semenov Guards[4], though he is denied a staff place with Kutuzov. Anna Mikhaylovna returns to Moscow and lodges with her wealthy cousins, the Rostovs, whose house on Povarskaya buzzes on St. Natalia’s day. Carriages clatter, visitors flow, while the countess and her eldest daughter receive congratulations; younger folk linger in inner rooms. The jovial count escorts each guest, repeating, ‘My dear, be sure to dine with us or I shall be offended!’ He strolls through the vast dining hall, praising the glittering table.

A towering footman intones, ‘Marya Lvovna Karagina and her daughter!’ The weary countess pinches snuff yet receives them. Dresses rustle, voices tumble over one another about Count Bezukhov’s failing health and his wayward son. ‘I’m so sorry for the poor count,’ sighs the visitor. ‘They say the police expelled the young man.’ ‘You don’t say so!’ the countess exclaims. Anna Mikhaylovna murmurs that Pierre, Dolokhov, and Anatole are ‘regular brigands’ who tied a policeman to a bear and dropped both into the Moyka. The count roars, ‘What a nice figure the policeman must have cut!’ and again invites everyone to dinner.

The countess smiled politely, signaling it was time to leave, when a crash next door announced thirteen-year-old Natasha, who darted in clutching something under her frock. Boris in scarlet collar, a Guards officer, Sonya, and Petya piled up behind. The count seized her, laughing, “Ah, here she is, my pet, name-day girl!” “Ma chere, there is a time for everything; you spoil her, Ilya,” the countess said. The visitor wished Natasha “many happy returns.” Natasha whipped out doll Mimi and collapsed in gales of laughter. When the lady asked, “Is Mimi a relation, a daughter?” she stared gravely while the young ones stifled giggles.

Boris joked he’d known Mimi before her nose cracked; Natasha blushed and fled, he went to fetch the carriage, Petya scowling after. Only Nicholas and cousin Sonya stayed. Her eyes adored him beneath a smile. The count boomed, “For friendship he leaves the Archives and me and joins the hussars with Colonel Schubert—there’s friendship!” “It isn’t that,” Nicholas flared; “the army is my vocation.” The visitor said, “They say war is declared.” “They always say so,” the count shrugged. Julie Karagina breathed, “Thursday was dull without you.” Nicholas leaned closer; Sonya rose, fled in tears, he followed, and Anna M sighed, “Cousinage—dangereux voisinage.

Once the brightness vanished the countess sighed, “How much anxiety one bears—at this age it is greater than joy.” The visitor answered, “It all depends on the bringing up.” The countess insisted she was always her children’s confidante and that impulsive Nicholas would never resemble the Petersburg boys. “Splendid youngsters!” cried the count, ending every problem by declaring it splendid. The guest called Natasha “a little volcano.” “Yes, a regular volcano,” laughed the count. “She’ll be a singer, a second Salomoni; we have engaged an Italian for lessons.” “Isn’t she too young? Training can harm a voice.” “Oh no—our mothers married at twelve or thirteen.

The countess smiled: “She’s already in love with Boris! If I forbade it they’d kiss in secret; as it is she tells me everything. I may spoil her, but it’s best. I was stricter with the elder.” “Yes, I was brought up differently,” said Vera, whose smile sharpened her features. The visitor sighed, “People are too clever with their eldest.” “True,” laughed the count, “but she’s turned out well.” The guests rose, promised to return for dinner, and filed out. “What manners, I thought they would never go,” muttered the countess. Natasha darted to the conservatory and, stamping, hid among the tubs when Boris approached.

Sonya ran inside; Nicholas followed. “Sonya, what’s wrong?” “Nothing, leave me!” “Why torment us for a fancy?” He seized her hand. “You alone are everything.” “Don’t speak so.” “Then forgive me,” he said and kissed her. Natasha thought, “How nice!” When they left she beckoned, “Boris, come.” Among the tubs she said, “Kiss the doll.” He waited; she whispered, “Would you kiss me?” Blushing, he hesitated; she jumped onto a tub, clasped his neck, and kissed him. “I love you,” he said, “but in four years I’ll ask your hand.” She counted on her fingers, smiled, “Settled forever?” “Settled.” Hand in hand they stepped out.

The countess refused callers and turned to Princess Anna Mikhaylovna. “Vera, show tact and leave,” she said. Vera entered the parlor where Nicholas copied verses for Sonya and Boris sat with Natasha. Brandishing an inkstand she snapped, “Stop taking my things. What secrets? Nonsense!” “Why care?” murmured Natasha. “You’ve never loved—Madame de Genlis!” “At least I don’t chase men before visitors,” Vera retorted. “Now you’ve upset everyone; let’s go,” Nicholas sighed, and the four slipped away shouting the nickname. Vera smoothed her hair. In the drawing room the countess sighed over money; Anna answered, “God spare you widowhood—I besiege great men till they yield.

“Whom did you approach about Bory?” the countess asks. Anna answers, glowing, “Prince Vasili; he agreed at once and placed the matter before the Emperor.” The countess wonders if the prince has aged, recalling past attentions. “He’s the same,” Anna says, quoting, “ ‘I’m sorry I can do so little, dear Princess; command me.’ ” Tears follow: her lawsuit drags, she owns one twenty-five-ruble note, needs five hundred to equip Boris. She eyes the dying Count Bezukhov, Bory’s godfather. “I’ll go to him now; gossip be hanged,” she decides, whispering, “Wish me luck.” Count Rostov adds, “If he’s better, ask Pierre to dine; Taras will excel.

In the carriage Anna strokes her son’s arm. “Be affectionate; your fate depends on your godfather.” Boris sighs, “I’ve promised, though only humiliation may come.” They reach Bezukhov’s straw-strewn entrance. The porter, eyeing Anna’s worn cloak, says the count is worse and receives no one. “My dear,” she whispers, and pleads, “I am a relation; let me see Prince Vasili.” The bell rings; a footman announces “Princess Drubetskaya.” She straightens her dyed silk at the mirror, prods Boris—“you promised”—and climbs the stairs. In the spacious hall Prince Vasili, escorting Doctor Lorrain, says, “Then it’s certain?” “Humanum est errare,” the doctor murmurs.

Prince Vasili dismisses the doctor and turns. Anna greets him sadly; Boris bows. He signals despair. “This is my son; he wished to thank you.” “A mother’s heart never forgets,” she adds. Adjusting lace, Vasili warns, “Serve well and show yourself worthy. Are you on leave?” “Awaiting orders to join the Guards, your excellency.” Hearing Boris stays with the Rostovs, he scoffs, “How could Nataly marry that bear and gambler!” Anna praises Rostov, murmurs about preparing the count’s soul. Vasili hesitates; she persists. A princess complains of noise. Anna trills, “I’m here to help.” Ignored, she removes gloves, sinks into an armchair, and beckons Vasili.

"Boris," she said with a smile, "I will visit the count; you must see Pierre and give him the Rostovs’ dinner invitation. I suppose he won’t come?" Turning to the prince, she waited. "On the contrary," he answered, depressed, "I’ll be grateful if you free me from that young man; the count never asks for him." He shrugged. A footman guided Boris down one stair, up another, to Pierre’s door. Pierre, recently expelled from Petersburg for tying a policeman to a bear, had been in Moscow several days, staying at his ailing father’s mansion.

Pierre entered the princesses’ drawing room: one read, two stitched. At his greeting their faces stiffened, the youngest ducking to hide a grin. “How do you do, cousin? Don’t you know me?” “Too well. The count suffers, and you worsen it; if you mean to finish him, go in,” she said, sending Olga for beef tea. Pierre bowed and left amid the youngest’s laughter. Next day Prince Vasili warned, “Repeat your Petersburg antics and you’ll end badly; the count is very ill, you must not see him.” Confined upstairs, Pierre paced like Napoleon until a well-built young officer was shown in.

Boris Drubetskoy entered. Pierre gripped him yet could not place him. The officer brought the Rostovs’ dinner note; Pierre mistook him for Ilya and recalled Sparrow Hills. “You’re mistaken,” Boris said, “I’m Boris, Princess Anna Mikhaylovna’s son.” Pierre, abashed, shifted to Napoleon. Boris, unimpressed, replied that Moscow gossiped only of the count’s fortune and that he and his mother would never seek it. Pierre praised such candor, accepted dinner, and shook his hand. Alone, he paced, smiling, sure they would be friends. That night Prince Vasili set Anna in her carriage; she wept for will as Boris listened, while Countess Rostova dried eyes and rang.

“What’s wrong with you, my dear? Don’t want to serve me? I’ll find another.” “Very sorry, ma’am.” “Call the count.” He waddled in. “Well, countess, the sauté au madère is splendid; Taras earned his thousand.” Leaning forward he asked, “Your commands?” She brushed a spot on his waistcoat. “I need five hundred rubles.” He took out his wallet. “Dmitri! Bring seven hundred, clean notes for the countess.” “At once, sir?” “At once, clean, please.” Dmitri exited. The count chuckled, “What a treasure; nothing’s impossible.” “Money, Count—how much sorrow it brings, yet I need it.” “Spendthrift!” He kissed her hand and left.

When Anna Mikhaylovna returned from Bezukhov, a neat pile of clean notes lay beneath a handkerchief on the countess’s table, and suspense shadowed her face. “Well, my dear?” the countess asked. “He is terribly ill; I scarcely spoke,” Anna murmured. The countess suddenly blushed. “Annette, for heaven’s sake, don’t refuse me.” She drew out the money. Anna understood, bent forward. “This is for Boris, for his outfit.” She embraced the countess and wept; the countess wept too. They cried for friendship, kindness, money’s humiliation, their vanished youth, and those shared tears felt sweet to them both.