27,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

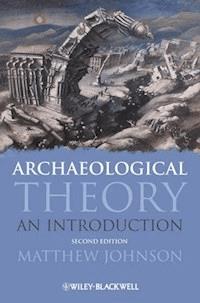

Archaeological Theory, 2nd Edition is the most current and comprehensive introduction to the field available. Thoroughly revised and updated, this engaging text offers students an ideal entry point to the major concepts and ongoing debates in archaeological research. * New edition of a popular introductory text that explores the increasing diversity of approaches to archaeological theory * Features more extended coverage of 'traditional' or culture-historical archaeology * Examines theory across the English-speaking world and beyond * Offers greatly expanded coverage of evolutionary theory, divided into sociocultural and Darwinist approaches * Includes an expanded glossary, bibliography, and useful suggestions for further readings

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 608

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

List of Figures

Acknowledgements

Preface: The Contradictions of Theory

1 Common Sense is Not Enough

Definitions of Theory

Understanding Theory

2 The ‘New Archaeology’

Culture History

Origins of the New Archaeology

New Archaeology: Key Points

Case Study: The Enigma of the Megaliths

Conclusion

3 Archaeology as a Science

Definitions of Science

Positivism

Examples

Objections to ‘Science’

Kuhn and Feyerabend

Social Constructivism

4 Middle-range Theory, Ethnoarchaeology and Material Culture Studies

Binford and Middle-range Theory

Interpreting the Mousterian

Uniformitarian Assumptions

Case Study: Bones at Olduvai

Middle-range Theory: Problems

Behavioural Archaeology

Material Culture Studies

5 Culture and Process

Culture History

Cultural Systems: Summary

The Idea of Process

Example: Cultural Process around the North Sea

Cultural Process: Strengths

The Context of Cultural Systems

Processual Thinking: Drawbacks

Processual Thinking Modified

Culture, Process and the Individual

6 Thoughts and Ideologies

Looking at Thoughts

Structuralism

Marxism

Ideology

Cognitive Archaeology

Conclusion

7 Postprocessual and Interpretive Archaeologies

Postprocessual Archaeology

Case Studies: Rock Art and Medieval Houses

Phenomenology

8 Archaeology, Gender and Identity

Gender

Bias Correction

Critique of Archaeological Practice

Archaeologies of Gender

Men, Women and Knowledge

Case Study: What This Awl Means

Archaeologies of Identity

Performativity

Conclusion

9 Archaeology and Cultural Evolution

Darwin, Marx and Spencer

Cultural Evolution

Criticisms of Cultural Evolution

Multilinear Evolution

Cultural Evolution and Marxism

Origins of the State

Case Study: Cahokia

Cultural Evolution Strikes Back

10 Archaeology and Darwinian Evolution

Darwin’s Dangerous Idea

Cultural Ecology

Genes and Memes

Co-Evolutionary Theory

Selectionist Archaeology

Case Study: Art, Handaxes, Population and Innovation in the Palaeolithic

Darwinian Archaeologies: Criticisms

Conclusion

11 Archaeology and History

Traditional History

The Annales School

The Linguistic Turn

Historical Archaeology

Historical Archaeology and the Text

Case Study: Bodiam Castle

Conclusion

12 Archaeology, Politics and Culture

Archaeology is Not in a Vacuum

Case Study: African Burial Ground

Indigenous Archaeologies

Multiculturalism, Diversity and Inclusion

The Relativism Question

13 Conclusion: The Future of Theory

Where We Are Now

The Fall and Rise of Empiricism

Processual and Postprocessual Archaeologies

Agency

Materiality

Theorizing The Field

Where Theory Is Going

Progress and Impact

Diversity and Pluralism

Conclusion

Selective Glossary

Further Reading

Bibliography

Index

Alan Sorrell, ‘Falling Tower’, date uncertain. Sorrell (1904–74) was a neo-Romantic artist known both for his ‘reconstruction’ drawings of archaeological sites and depictions of past cultural life, and for his ‘imaginative’ work, which was characteristically inspired by the monuments and images of the past.

For Jo,

who learnt to love theory

This second edition first published 2010

© 2010 Matthew Johnson

Edition history: Blackwell Publishing Ltd (1e,1999)

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Matthew Johnson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Johnson, Matthew, 1962–

Archaeological theory : an introduction / Matthew Johnson. – 2nd ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-0014-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4051-0015-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Archaeology–Philosophy. I. Title.

CC72.J65 2010

930.1–dc22

2009039202

List of Figures

Preface: ‘You’re a terrorist? Thank God. I understood Meg to say you were a theorist.’ From Culler (1997: 16)

2.1The gulf between present and past2.2Illustration of burial urns from Sir Thomas Browne, Hydriotaphia (1658)2.3‘Cultures’ in space and time, from Childe (1929)2.4Piggott’s (1968) view of culture2.5David Clarke’s (1976) systemic view of culture2.6Glyn Daniel’s (1941) view of megalith origins2.7Renfrew’s megaliths on Rousay, Orkney Islands, showing ‘distribution of chambered tombs in relation to modern arable land, with hypothetical territorial boundaries’3.1Lon Chaney, Jr and Lionel Atwill in Man Made Monster (1941, Universal)3.2A selective diagram showing some schools within the philosophy of science4.1Present statics, past dynamics and middle-range theory4.2Bordes’ Mousterian assemblage types, as redrawn by Binford (1983a)4.3Part of Hillman’s (1984) ethnoarchaeological model of grain processing, derived from ethnographic research in Turkey5.1David Clarke’s (1976) diagram of the normative view of culture5.2A systems model of the ‘rise of civilization’ in Mesopotamia 787.1The results of Hodder and Orton’s simulation exercise showing that ‘different spatial processes can produce very similar fall-off curves’, implying that ‘this advises great caution in any attempt at interpretation’7.2The relationship of theory and data in postprocessual archaeology7.3(a) Carvings from Nämforsen, (b) part of Tilley’s structural scheme for interpreting the carvings7.4A medieval hall (after Johnson 1989: figure 2)8.1Prehistoric life according to children’s books. From Unstead (1953: 20)8.2The awl handle excavated by Spector’s8.3The elderly Mazaokeyiwin working a hide9.1St George and the Dragon, as depicted on St George’s Altarpiece, National Gallery, Prague, c.14709.2A Native American chief, drawn by John White in the 1580s9.3An ‘Ancient Briton’, drawn by John White in the 1580s9.4Clarke’s contrast between organic and cultural evolution9.5Artist’s impression of the site of Cahokia at its peak, by William R. Iseminger10.1Charles Darwin, from a cartoon in 187110.2An entangled bank, close to Down House, Darwin’s home10.3William ‘Strata’ Smith’s map of the geology of the British Isles10.4Handaxes from Cuxton, southern England11.1Bodiam Castle11.2Bodiam Castle: plan of landscape context12.1A coffin from the African Burial Ground, New York. The heart shape is made of tacks; it has been interpreted as a west African symbol13.1Archaeological theory in 198813.2Archaeological theory in 199813.3Archaeological theory in 2008: the struggle between different elements of thought and activity, in the mind of every archaeologistAcknowledgements

The author and publishers gratefully acknowledge the following for permission to reproduce copyright material:

Acknowledgements

Preface cartoon © Anthony Hadon-Guest; figure 2.2 from Childe, V. G., The Danube in Prehistory (Oxford University Press, 1929); figure 2.4 copyright © 2010 by Transaction Publishers. Reprinted by permission of the publisher; figure 2.5 from Clarke, D., Analytical Archaeology (second revised edition) (Routledge, London, 1976); figure 2.6 from Daniel, G. E., ‘The dual nature of the megalithic colonisation of prehistoric Europe’, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 7, 1941, courtesy of The Prehistoric Society, Salisbury; figure 2.7 from Before Civilisation: A RadiocarbonRevolution and Prehistoric Europe by A. C. Renfrew, published by Century. Reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Ltd.; figure 3.1 © The Kobal Collection; figure 4.3 from Hillman, G., ‘Interpretation of archaeological plant remains’, reprinted from Lone, F. A., Khan, M. and Buth, G. M., Palaeoethnobotany – Plants and Ancient Man in Kashmir (A A Balkema, Rotterdam, 1993); figure 5.1 from Clarke, D., AnalyticalArchaeology (second revised edition) (Routledge, London, 1976); figure 7.1 from Hodder, I. and Orton, C., Spatial Analysis in Archaeology (Cambridge University Press, 1976); figure 7.3 from Tilley, C., MaterialCulture and Text: The Art of Ambiguity (Routledge, London, 1991, © Dr Christopher Tilley); figure 8.1 from Unstead, R. J., Looking at History1: From Cavemen to Vikings (Black, London, 1953); figure 8.2 © Klammers and the University of Minnesota Collections; figure 8.3 © Minnesota Historical Society; figure 9.1http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_George_and_the_Dragon-altar_wing-NG-Praha.jpg; figure 9.2 © The British Museum, London; figure 9.3 © The British Museum, London; figure 9.4 from Clarke, D., Analytical Archaeology (Routledge, London, 1976); figure 10.1 Private collection/The Bridgeman Art Library Nationalaity; figure 10.2 © Crown copyright, RCHME; figure 10.3 © Royal Geographical Society, London/The Bridgeman Art Library; figure 11.2 © Crown copyright NMR.

The publishers apologize for any errors or omissions in the above list and would be grateful to be notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in the next edition or reprint of this book.

Preface: The Contradictions of Theory

This book is an introductory essay on archaeological theory. It tries to explain something of what ‘theory’ is, its relationship to archaeological practice, how it has developed within archaeology over the last few decades, and how archaeological thought relates to theory in the human sciences and the intellectual world generally.

To many, ‘theory’ is a dirty word both within and outside archaeology. Prince Charles earned almost universal approbation when he condemned ‘trendy theorists’ in education; nobody however, including the Prince himself, seemed to be very clear precisely who he meant. When visiting an archaeological site a few years ago a suggestion of mine met with laughter and the response ‘that’s a typical suggestion of a theorist’. I don’t recall anyone telling me exactly why my suggestion was so absurd, and when I visited the site the following year the strategy had been adopted. For the meat-and-potatoes Anglo-Saxon world in particular, theory is an object of profound suspicion. It is a popular saying that for the English, to be called an intellectual is to be suspected of wanting to steal someone’s wife (sexism in the original). Theory, ‘political correctness’ and being ‘foreign’ stand together in the dock as traits to be regarded with hostility in the Englishspeaking world–and beyond; there is even a word for hostility to theory in German–Theorifeindlichkeit. I shall look at some of the reasons why this is so in chapter 1.

At the same time, however, theory is increasingly popular, and seen as increasingly important, both within and outside archaeology. Valentine Cunningham commented in The Times Higher Education Supplement that theorists in academia are ‘a surging band, cocky, confident in academic credentials, job security and intellectual prestige’, inspiring the columnist Laurie Taylor to write a memorable account of a bunch of theorists intellectually roughing up a more empirical colleague at a seminar before departing to the local bar. His account was fictitious but contained much truth.

‘You’re a terrorist? Thank God. I understood Meg to say you were a theorist.’ From Culler (1997: 16)

There are various indices of the ‘success’ of an explicitly defined archaeological theory; one might cite the frequency of ‘theoretical’ symposia at major conferences such as the Society for American Archaeology or the European Association of Archaeology, or the incidence of ‘theory’ articles in the major journals. One particularly telling index is the rise and rise of the British Theoretical Archaeology Group conference (TAG). This was formed as a small talking-shop for British archaeological theorists in the late 1970s, but since then has become the largest annual archaeological conference in Britain with substantial participation from North America and Europe. There are now similar organizations in North America, Scandinavia (NordicTAG) and Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Theorie).

It is true that a lot of papers delivered at TAG scarcely merit the term ‘theoretical’, and even more true that many only come for the infamous TAG party in any case. It must also be conceded that the degree of impact of TAGs and ‘theory’s’ influence on the ‘real world’ of archaeological practice, and the cultural and legislative framework of archaeology, is debatable. The theorist often feels like Cassandra, constantly giving what he or she sees as profound predictions and insight and constantly being ignored by the decision makers.

This book is written to give the student an introduction to a few of the strands of current thinking in archaeological theory. It is deliberately written as an introduction, in as clear and jargon-free a fashion as the author can manage (though as we shall see, criteria of clarity and of what constitutes jargon are riddled with problems).

It is intended as a ‘route map’ for the student. That is, it seeks to point out prominent landmarks on the terrain of theory, comment on relationships between different bodies of thought, and to clarify the intellectual underpinnings of certain views. As such, it is anything but an encyclopaedia; it is hardly one-tenth of a comprehensive guide to the field, if such a guide could be written. The text should be read with reference to the Further Reading and Glossary sections, and over-generalization, oversimplification and caricatures of viewpoints are necessary evils.

Above all, I remind all readers of the fourth word in the title of this book. I have tried to write an Introduction. The book, and its different chapters, are meant to be a starting-point for the student on a range of issues, which she or he can then explore in greater depth through the Further Reading sections. Many of the comments and criticisms made of the first edition of this book focused on an alleged over-or under-emphasis of a particular theoretical viewpoint, or lack of coverage. Many of these criticisms were valid, and I have tried to deal with them in this second edition; but many evaluated the text as a position statement with which they happened to agree or disagree, rather than on its pedagogical intention, that is as an introductory route-map to the issues. Additionally, students need to be reminded that this book should be the start, not the end, of their reading and thinking, a point I will return to in the Conclusion. A route-map is not an encyclopaedia.

To pursue the route map analogy, the route followed here is one of several that could be taken through the terrain of archaeological theory. I could have devoted a chapter each to different thematic areas: Landscape, The Household, Trade and Exchange, Cultures and Style, Agency, and so on. In each case, a variety of approaches to that theme could be given to show how different theories contradict or complement each other and produce different sorts of explanation of the archaeological record. Alternatively, a tour could be taken through different ‘isms’: positivism, functionalism, Marxism, structuralism, poststructuralism, feminism. These would be reasonable paths, and ones moreover that have been taken by other authors.

This book, however, tries above all to bring out the relationship between archaeological thought and wider strands of theory in intellectual and cultural life as a whole. It seeks to show how specific theoretical positions taken by individual archaeologists ‘make sense’ within a wider context, cultural, social and political as well as academic. This book also seeks to bring out the relationship between archaeological theory and archaeological practice more clearly than has been done in the past. The structure adopted here, of a historical approach focusing initially on the New Archaeology and reactions to it before moving on to current debates, fitted this purpose best.

I have written above that this book is a guide for ‘the student’; I mean the student in the broadest sense. Many practising archaeologists employed outside the academic world have told me that they are interested in current theoretical debates, and see such debates as of potential relevance to their work. Nevertheless many feel alienated by what they see as the unnecessary obscurity and pretentiousness that is central to the theoretical scene. I don’t subscribe to such an analysis, but I have to acknowledge that it is widespread. Right or wrong, I hope that they may find that what follows is of some help.

In trying to survey many different theoretical strands, I have been torn between trying to write a ‘neutral’, ‘objective’ survey of different currents of thought on the one hand, and a committed polemic advancing my own views on the other. The end product lies, perhaps a little unhappily, somewhere between these extremes. On the one hand, the construction of a completely objective survey simply isn’t intellectually possible; the most biased and partial views on any academic subject consistently come from those who overtly proclaim that their own position is neutral, detached and valuefree. In addition, it would be disingenuous to claim that the book is written from a disinterested viewpoint–that it is a guide pure and simple. Obviously an interest in theory goes hand-in-hand with a passionate belief in its importance, and an attachment to certain more or less controversial views within the field.

On the other hand, if we want to understand why theory is where it is today, any account of a wide diversity of intellectual positions must endeavour to be reasonably sympathetic to all parties. A survey can never be neutral, but it can make some attempt to be fair. As R.G. Collingwood pointed out in relation to the history of philosophy, most theoretical positions arise out of the perceived importance of certain contexts or issues; that is, philosophical beliefs are in part responses to particular sets of problems, and have to be understood as such rather than given an intellectual mugging. One’s intellectual opponents are never all morons or charlatans to the last man and woman and one’s bedfellows are rarely all exciting, first-rate scholars. Before we get carried away with such piety it must be remembered that this does not mean that certain positions are not therefore immune from criticism. An intellectual relativism in which ‘all viewpoints are equally valid’ or in which ‘every theory is possible’ is not a rigorous or tenable position. We can see historically that some theoretical positions have been abandoned as dead ends, for example the extreme logical positivism of the 1970s.

I have also been torn between writing a historical account of the development of theory, and of giving a ‘snapshot’ of theory in the present. On the one hand, it might be held that my re-telling of the origins of the New Archaeology of the 1960s, and more arguably the processual/postprocessual ‘wars’ of the 1980s and 1990s, is now out of date. On the other hand, I feel that in order for the student to understand where theory is today, it is necessary to look at its development over the last few decades, and indeed to look at the deeper intellectual roots of many views and positions in the more remote past, for example in the thinking of figures like Charles Darwin and Karl Marx. Much of traditional cultural evolutionary theory, and much of the early postprocessual critique, may appear to be passé to some; but I do not think that the modern student can understand current thinking without reference back to this literature. Archaeology would be a strange field of study if it asserted that it could understand the way the discipline thinks in the present, without reference back to the way it thought in the past.

For this second edition of the book, I have made a number of changes. I give a more extended account of these and reflection on them in the Further Reading section, but two stand out. First, there has been an explosion in archaeological discussion of Darwinian evolution, and I have therefore divided the chapter on ‘Evolution’ into two. Second, the first edition concentrated on theory in the Anglo-American world, in part reflecting my own background and limitations. This concentration was rightly criticized by many non-Anglo scholars. I have tried in this second edition to write a more inclusive text, giving more attention to Indigenous and postcolonial perspectives as well as drawing more attention to theoretical contributions from across the world. I have nevertheless retained the original structure of the book, and have run the risk of ‘fitting in’ material around this organizing structure; but the alternatives, for example of having a separate chapter on non-Anglo theory, or of a country-by-country survey, seemed to me to be greater evils and to do greater violence to the very subtle texture of theoretical debate.

The adoption of an informal tone and omission of detailed referencing from the text is deliberate. It is to help, I hope, the clarity of its arguments and the ease with which it can be read. Many ‘academic’ writers have often been taught to forsake the use of the ‘I’ word, to attempt to render our writing neutral and distant, to avoid a conversational or informal tone, all in the name of scientific or scholarly detachment. This may or may not be a valid project. The aim here however is educational rather than scholarly in the narrow sense.

One of my central points, particularly in the first chapter, is that all practising archaeologists use theory whether they like it or not. To make this point clear and to furnish examples I have often quoted passages from avowedly ‘atheoretical’ writers and commented upon them, to draw out the theories and assumptions that lie implicit within those passages. In most cases the passages come from the first suitable book to hand. I want to stress that critiques of these examples are not personal attacks on the writers concerned. Here, the need to use practical examples to make a theoretical point clear clashes with the desire to avoid a perception of unfair, personalized criticism.

The text is based in part on lecture notes for various undergraduate courses I have taught at Sheffield, Lampeter, Durham and Southampton. The students at all four institutions are thanked for their constructive and helpful responses. Some students may recognize themselves in the dialogues in some of the chapters, and I ask their forgiveness for this. The first edition of the book was partly conceived while I was a Research Fellow at the University of California at Berkeley in the spring of 1995. I would like to thank Meg Conkey, Christine Hastorf, Marcia Ann Dobres, Margot Winer and many others too numerous to mention for their hospitality during that time and for making my stay so enjoyable and profitable. I also thank Durham University for giving me study leave for that term. A number of reviewers, some anonymous, made a string of invaluable comments without which the book would have been much more opinionated and parochial and much less comprehensible. These include especially Randy McGuire, Jim Hill, Chris Tilley and Elizabeth Brumfiel. Robert Preucel and Ian Hodder reviewed the final draft extensively. Tim Earle, Clive Gamble and Cynthia Robin kindly corrected my misconceptions for the second edition. Dominic McNamara drew my attention to the Foucault quotation in chapter 6. Within the Department of Archaeology at Durham, Helena Hamerow, Colin Haselgrove, Anthony Harding, Simon James, Sam Lucy and Martin Millett read and made invaluable comments on the first draft. Brian Boyd, Zoe Crossland, Jim Brown and John McNabb helped with illustrations. William R. Iseminger kindly supplied figure 9.5 and Francis Wenban-Smith kindly supplied figure 10.4. Collaboration with staff of the History, Classics and Archaeology Subject Centre, particularly Annie Grant, Tom Dowson and Anthony Sinclair, influenced my thinking on the pedagogical framing and impact of the second edition. Conversations on the philosophy of science with my late father C. David Johnson clarified many points.

I moved to Southampton in 2004; I thank an outstanding group of colleagues and students there for their advice and support over the last five years. I prepared revisions for the second edition while a visiting scholar at the University of Pennsylvania in the autumn of 2008. I thank Bob Preucel and Richard Hodges for making that visit possible, and the students of Bob’s theory class for their input and hospitality. I also thank Clare Smith, Heather Burke and Matt Spriggs for organizing a stimulating visit to Australia in 2003/4, and Prof Joseph Maran, Ulrich Thaler and the staff and students of Heidelberg University for four wonderful months discussing theory and practice in spring 2005.

More broadly, can I thank everyone who has taken the time to speak or write to me over the last ten years to express their appreciation for this book. Students, teachers and practicing archaeologists have given me some very kind compliments, for which I am flattered and grateful, from the Berkeley feminist who said that I wrote like a woman to the Flinders student who sent me a picture of her Matthew Johnson Theory Action Doll.

Conversations with Chris Taylor, Paul Everson, Casper Johnson and David Stocker informed the discussion of Bodiam in chapter 10, though errors and misconceptions in this discussion remain my responsibility. John Davey, Tessa Harvey, Jane Huber, Rosalie Robertson and Julia Kirk at Blackwell were always patient, encouraging and ready with practical help when needed. My wife Becky made comments on successive drafts; proofread the final manuscript; and most importantly, provided emotional and intellectual support without which this book would never have been written. In return, I hope this book explains to her why archaeologists are such a peculiar bunch of human beings, though I know she has her own theories in this respect. My thanks to everybody.

1

Common Sense is Not Enough

Archaeology can be very boring, distressing and physically uncomfortable. Every year we excavate thousands of sites, some with painstaking and mind-numbing patience, some in a great and undignified hurry. Every year we get chilled to the marrow or bitten half to death by mosquitoes while visiting some unprepossessing, grassy mound in the middle of nowhere. Miles from a decent restaurant or even a warm bath, we try to look interested while the rain comes down in sheets and some great professor whose best work was 20 years ago witters on in a monotone about what was found in Trench 4B. Every year we churn out thousands of interminable, stultifyingly dull site reports, fretting over the accuracy of plans and diagrams, collating lists of grubby artefacts to publish that few will ever consult or use again.

Why?

We could spend the money on hospitals. Alternatively we could quietly pocket the cash and write a much more entertaining, fictitious version of what the past was like while we sat on a sun-kissed terrace somewhere in southern California. If we were feeling ideologically sound we could raise an International Brigade for a liberation struggle somewhere. Each of these alternatives has its attractions, but we don’t do any of these things. We go on as we have done before.

One reason we don’t do these things is because archaeology is very important. The past is dead and gone, but it is also very powerful. It is so powerful that an entire nation (Zimbabwe) can name itself after an archaeological site. It is so powerful that archaeological sites are surrounded by police and are the subject of attempted occupations by New Age travellers. It is so powerful that even individual groups of artefacts like the Parthenon frieze are the subject of major international disputes.

The question ‘why do we do archaeology?’ is therefore bound up with the question ‘why is archaeology – the study of the past through its material remains – so important to us?’ And this again leads on to the question of ‘us’, of our identity – who are we? And these are all theoretical questions.

Definitions of Theory

‘Theory’ is a very difficult word to define. Indeed, I shall return to this topic in the final chapter, since different theoretical views define ‘theory’ in different ways. Different definitions cannot therefore be fully explored without prior explanation of those views.

For the time being, I propose to define theory as follows: theory is theorder we put facts in. I will go on to discuss the extent to which ‘facts’ exist independently of theory, and how we might define ‘facts’. We can also note that most archaeologists would include within the purview of theory whywe do archaeology and the social and cultural context of archaeology. They would also refer to issues of interpretation. Most archaeologists would agree that the way we interpret the past has ‘theoretical’ aspects in the broad sense. For example, we could cite general theories such as cultural and biological evolution, issues of how we go about testing our ideas, debates over how we should think about stylistic or decorative change in artefacts.

There is disagreement over whether many concepts can be considered ‘theoretical’ or whether they are merely neutral techniques or methods outside the purview of theory. Stratigraphy, excavation and recording techniques, and the use of statistical methods are, for example, clearly all examples of putting facts in a certain order. However, they might be considered ‘theoretical’ by some but ‘just practical’ or ‘simply techniques’ by others. Theory and method are often confused by archaeologists. In this more restricted sense of theory, if theory covers the ‘why’ questions, method or methodology covers the ‘how’ questions. So theory covers why we selected this site to dig, method how we dig it. However, theory and method are obviously closely related, and many archaeologists including myself regard such a straightforward division as too simple.

To give an example of the relationship between theory and method, we might consider different methods of investigating social inequality in the archaeological record. Thus the method archaeologists might use would be to compare graves ‘richly’ endowed with lots of grave goods with poorer, unadorned graves. It is evident in this exercise that certain ideas or theories about the nature of social inequality are being assumed (that social status will be reflected in treatment of the body at death, that material goods are unequally distributed through society and that this has a direct relationship to social inequality, and so on). These ideas are themselves theoretical in nature.

Perhaps theory and method are one and the same thing and cannot be separated; perhaps they have to be separated if archaeology is to be a rigorous discipline that is capable of testing its theories against its data. This is a debate we shall return to in chapter 4.

I’m sorry to butt in, but all this discussion of theory and method clearly demonstrates just how sterile and boring theory really is. You’re already lost in definitions and semantics, you haven’t mentioned a single fact about the past, and I’m beginning to wish I hadn’t bothered to start reading this and had turned my attention to that new book about the Hopewell culture instead. Theory is irrelevant to the practice of archaeology; we can just use our common sense.

Ah, Roger, the eternal empiricist. (Roger Beefy is an undergraduate student at Northern University, England, though women and men like Roger can be found in any archaeological institution. Roger fell in love with archaeology when he was a child, scrambling up and down the ruins of local castles, churches, burial mounds and other sites. Roger spent a year after school before coming to Northern University digging and working in museums. Roger loves handling archaeological material, and is happiest when drawing a section or talking about seriation techniques over a beer. Now, in his second year at Northern University, Roger has found himself in the middle of a compulsory ‘theory course’. Full of twaddle about middle-range theory, hermeneutics and postcoloniality, it seems to have nothing to do with the subject he loves.)

So, you want to know why theory is ‘relevant’ to archaeological practice. Perhaps you will bear with me while I discuss four possible reasons.

1 We need to justify what we do

Our audience (other archaeologists, people in other disciplines, the ‘general public’ or ‘community’ however defined) needs to have a clear idea from archaeologists of why our research is important, why it is worth paying for, why we are worth listening to. There are a hundred possible answers to this challenge of justification, for example:

The past is intrinsically important, and we need to find out about it for its own sake.We need to know where we came from to know where we’re going next. Knowledge of the past leads to better judgements about the future.Only archaeology has the time depth of many thousands of years needed to generate comparative observations about long-term culture processes.Archaeology is one medium of cultural revolution that will emancipate ordinary people from repressive ideologies.The chances are that you disagree with at least one of these statements, and agree with at least one other. That doesn’t change the fact that each statement is a theoretical proposition that needs justifying, arguing through, and debating before it can be accepted or rejected. None of the statements given above is obvious, self-evident or common-sensical when examined closely. Indeed, very little in the world is obvious or self-evident when examined closely, though our political leaders would have us think otherwise.

2 We need to evaluate one interpretation of the past against another, to decide which is the stronger

Archaeology relies in part for its intellectual credibility on being able to distinguish ‘good’ from ‘bad’ interpretations of the past. Were the people who lived on this site hunter-gatherers, or were they aliens from the planet Zog? Which is the stronger interpretation?

It’s impossible to decide what is a strong archaeological interpretation on the basis of ‘common sense’ alone. Common sense might suggest, for example, that we accept the explanation that covers the greatest number of facts. There may be thousands of sherds of pottery dating from the first millennium BC on a site, all factual in their own way, but one other fact – a treering date of ad 750, for example – may suggest that they might be all ‘residual’ or left over from an earlier period. In practice, every day of our working lives as archaeologists, we decide on which order to put our factsin, what degree of importance to place on different pieces of evidence. When we do this, we use theoretical criteria to decide which facts are important and which are not worth bothering with.

A good example of the inadequacy of common sense in deciding what is a strong or weak archaeological explanation is that of ley lines. Ley lines were ‘discovered’ by Alfred Watkins in the 1920s, when he noticed that many ancient archaeological sites in Britain could be linked up by straight lines. The idea that ancient sites lay on straight lines could be ‘proved’ easily by taking a map upon which such ancient monuments were marked and drawing such lines through them. Watkins suggested these lines represented prehistoric trackways. Nonsense, said the professional archaeological community. It was common sense that prehistoric peoples living thousands of years before literacy or formal geometry were far too primitive to lay out such geometrically sophisticated lines. Watkins had intended his book as a genuine contribution to archaeology, but his research, sincerely carried out, was laughed out of court and consigned to the ranks of lunatic ‘fringe archaeology’. Other writers took his thesis up in succeeding decades but extended it by suggesting that the lines were of sacred significance or mystical power.

Now it is quite clear today that prehistoric peoples would have been quite capable of laying out such lines. The original, common-sensical criteria used by archaeologists for rejecting Watkins’s thesis were completely invalid.

Ley lines do not exist. This was shown by Tom Williamson and Liz Bellamy in Ley Lines in Question, which analysed such lines statistically and showed that the density of archaeological sites in the British landscape is so great that a line drawn through virtually anywhere will ‘clip’ a number of sites. It took Williamson and Bellamy a book’s worth of effort and statistical sophistication to prove this, however.

The moral of the debate over ley lines is that what is considered to constitute a strong or a weak explanation is not simply a matter of ‘common sense’. I would argue that if we really want to understand what drove and continues to drive the ley line debate, we have to look, in part, at class divides in British archaeology. In his time Watkins was derided as a vulgar amateur, while today the tradition of ley line searchers continues strongly in ‘alternative’ or New Age circles. New Age travellers and others in their turn view middle-class professional archaeologists with suspicion. Others might dispute this social interpretation and suggest alternative reasons for the intellectual development of the issue. I might reply: we would then be having a theoretical debate.

3 We must be explicit in what we do as archaeologists

In other words, we must be as open as possible about our reasons, approaches and biases, rather than trying to conceal them or pretend that they do not exist. This is a basic rule of academic discourse, though it is not always followed. Lewis Binford, a character we shall meet properly in the next chapter, made the point that all scientists of all disciplines need to be aware of the assumptions they are making if they wish to be productive.

It goes without saying that we can never be completely explicit about our biases and preconceptions. This should not stop us trying.

4 We don’t ‘need’ theory, we all use theory whether we like it or not

Put another way, we are all theorists. This is the most important point of all. The most lowly troweller, the most bored washer of ceramics, the most alienated finds assistant or lab technician, are all theoreticians in the sense that they all use theories, concepts, ideas, assumptions in their work. (The theory may have been imposed on them by the project director or funding body, but it is theory nevertheless.) Put another way, the driest, most descriptive text or site report is already theoretical. Somebody wielding a WHS or Marshalltown trowel relies on theories of soil colour change and stratigraphy in his or her work; editorial judgements about the relative weighting and order given to pottery and artefact reports in a site monograph depend on a judgement on what is ‘significant’ about that particular site which in turn rests on theoretical criteria.

Any archaeologist who therefore tells you that their work is ‘atheoretical’, that they are ‘not interested in theory’, or that they are doing ‘real archaeology’ as opposed to those ‘trendy theorists’ is not telling the whole truth. They are as much theorists as anyone else, though they might choose to mask their theoretical preconceptions by labelling them ‘common sense’ or derived from the ‘real world’. In doing so, I would argue that they are bypassing their responsibility to make clear the intellectual basis of their work, trying to hide the theoretical assumptions and approaches that they are in fact using from critical scrutiny. They are indulging in an intellectual sleight of hand.

I would go further: pretending to be atheoretical is an attempt to impose a kind of machismo on to archaeological practice. As we shall see in chapter 8, archaeological practice is bound up with gendered notions of what is or is not valuable. There is, at least in the English-speaking world, always something vaguely effeminate (and therefore, it is implied, somehow secondary) about talking, reasoning, discussing, trying to think clearly and explicitly. It is difficult to see Vin Diesel at a philosophy discussion group. ‘Real men’ don’t do isms and ologies; they just dig – preferably with a really large, heavy pickaxe.

I’ve listened long enough to this; you’re descending into abuse now.I’m willing to concede that we all use theory in some sense, but atthe end of the day it’s the facts, the raw data, that count.

I’m not going to argue now about whether ‘raw data’ really exist independently of theory – that will come later. Let’s suppose for now that raw data really do exist. Where does that get us? There is an infinity of archaeological facts. They are piled in their millions in museum and laboratory storerooms, in microfiche lists and in tables of data. Here are some pretty undeniable ‘facts’:

The pot I am holding is 600 years old.

Cuzco is an Inca site in Peru.

Lepenski Vir is a Mesolithic site in Serbia.

Colono Ware pottery has been found in Virginia.

A skeleton was excavated at Maiden Castle, Dorset, England, with an iron projectile lodged in its spine.

Great Basin projectile points come in different sizes.

The Bronze Age preceded the Iron Age.

Tikal was a major ceremonial centre for the Ancient Maya.

There are usually lots of clay pipe fragments on post-1500 sites. The Dordogne area of France is full of cave art.

The Great Wall of China is studded with towers.

In Chaco Canyon the ancient pueblos are built of stone.

Do the sentences above add up to a meaningful account of the past, a coherent archaeological narrative? No. Simply dredging up facts and waiting for them to cohere into an orderly account of the past is like putting a number of monkeys in front of typewriters and waiting for them to come up with the complete works of Shakespeare.

What makes us archaeologists as opposed to mindless collectors of old junk is the set of rules we use to translate those facts into meaningfulaccounts of the past, accounts that ‘make sense’ to us as archaeologists and (it is hoped) to those who read or engage with our work. And those rules, whether they are implicit or explicit, are theoretical in nature. Facts are important, but without theory they remain utterly silent.

Let’s take the example of a distinguished Professor of Archaeology who claims to be writing in an atheoretical, factual manner using ‘common sense’, and see what he is really doing. I have selected this text more or less at random:

It is worth stressing that Romano-British culture was based on a money economy. In south-eastern Britain coins were indeed in use before the conquest, but the Romans were responsible for spreading their circulation throughout the island. The extent to which currency permeated the whole commercial life of the country, down to the smallest transactions, may be gauged from the occurrence of coins on the humblest Romano-British sites and in the remotest part of the province. (Alcock 1976: 174)

One theoretical assumption being made here is that ideas like ‘transaction’ and ‘commercial life’, which only gain their modern meaning in the later eighteenth century and only arguably so even then, can easily be applied to Roman Britain without further explication. It follows that the writer must expect the reader to use his or her modern experience of transactions and commercial life – market oriented, largely unconnected with social relations, mediated by a common means of monetary exchange – to understand the meaning of the sentence. This and other assumptions may or may not be true, but they are theoretical in nature.

A second is a ‘middle-range’ assumption: that is, it connects particular facts on the one hand to general theories on the other (see chapter 4). Alcock assumes that the relative numbers of coins on different site types (note the use of an implicit site hierarchy that equates with a social hierarchy, assumed rather than demonstrated: ‘the humblest sites’) will accurately reflect the level of what Alcock has termed ‘commercial activity’. Of course, we have already acknowledged that commercial activity is a much more theoretically complex beast. Again, this is a theoretical proposition.

Alcock’s account may or may not be ‘true’, a ‘fair picture’ or ‘valid’; that is a matter for debate among those specializing in this period. It is certainly deeply theoretical. I could go on analysing the passage for several more pages, but the point has been made that even the most apparently straightforward, transparent, ‘clear’ prose conceals theoretical depths.

All this is very plausible and convincing, but I still dislike theory intensely. Theorists seem constantly to use incomprehensiblejargon, write in an impenetrable style, and never to get anywheretangible. You might persuade me there is a point to theory, but youcan’t stop me being irritated and alienated by what theoristswrite.

No, I can’t. I get irritated by a lot of theoretical writing, just as I get irritated by all sorts of archaeological writing. But you’ve raised a lot of points here that are worth taking in turn.

First, why the ‘jargon’? Long words with specialized meanings are not confined to archaeological theory. Every area within archaeology has its own specialist terms of reference; in this sense jargon is in the eye of the beholder. My familiar terms as a theorist or as a specialist in vernacular architecture may seem jargon to the environmental specialist, and those of the environmental specialist may equally seem jargon to me.

There is a deeper problem with the accusation of jargon, however. There seems to be an assumption behind such an accusation that we can always express what we want to say in ‘clear, simple and easy’ language. If only archaeology were so straightforward! If it were, we might have concluded the archaeological project with a perfect understanding of the past hundreds of years ago. Archaeology is, if nothing else, about new ideas about the past. We express ideas in words, and it may be appropriate to use new words to lead the reader to think in new ways.

Human societies were and are very complex things. As part of the natural world they share its complexity, and also have a social and cultural complexity all of their own. We don’t complain when the chemist or biologist uses technical language incomprehensible to the lay person, so why should we when the archaeologist does so?

The point I am making here is that archaeologists expect the finer techniques of archaeological practice to be difficult to comprehend and master; that is the nature of our discipline. We are prepared to put effort into mastering the language and practice of stratigraphy, Harris matrices, seriation, scientific dating techniques, even the half-intuitive practical skill of differentiating between layers by the feel of the soil under the trowel. But the ‘theory’ side of what we do – using the tiny scraps of information thus gained to tell us about the human past in all its richness and complexity – must be at least equally difficult as these ‘practical’ tasks. It fact, it must be one of the most intellectually demanding tasks we as a species have ever set ourselves.

I think you’re missing the point. The suspicion is that jargon isbeing used to mystify, to create a language of exclusion where theoutsider is made to feel small.

There is some justice in this charge. Certain forms of academic rhetoric are used, intentionally or unintentionally, to set up in-groups and out-groups. I do not defend such a practice. But again, one hears the vague murmur of pots calling kettles black; all sectional interests within and outside archaeology do this. Read any article in Vernacular Architecture on the classification of scarf-joints with squinted and pegged abutments, or a medieval historian on enfeoffments and subinfeudation.

Finally, ‘writing clearly’ assumes that one is writing about something else. In other words, that there is a real, external world out there with certain essential, concrete features, features that language can describe in a more or less clear and neutral manner. Now whether one is describing the decoration on pots or suggesting what it might have been like to live in the Bronze Age, this is a highly debatable assumption. Certainly, in most traditions of Western thought, the past doesn’t exist anywhere outside our own heads. I have never touched, kicked or felt the past.

Theory is difficult. If one accepts that all archaeologists are theorists, then logically it is no more or less difficult than any other branch of archaeology. But archaeology itself is difficult. We have set ourselves an incredibly daunting task. We want to understand human societies that have been dead and gone for thousands of years, whose customs, values and attitudes were almost certainly utterly different from our own. We have to do this without talking to the people themselves. What is more, we want to understand how and why they changed in the way they did. And the only materials we have to achieve this immense task are a few paltry scraps of rubbish they left behind on the way, most of which have long since decayed into dust. Such a task is not a simple one; the wish that, for all its practical discomforts and difficulties, it be an intellectually easy one is quite understandable, but very naïve.

Theory is also difficult for reasons that have less to do with jargon as such and more to do with academic practice. Practitioners in theory will often say one thing and do quite another. A theoretical article will proclaim that it is tackling a problem from a new, exciting perspective and just churn out the same old approach thinly disguised. Another article will accuse a rival of a string of theoretical iniquities and then do exactly the same things itself using different language.

Which leads to my final point: theory is difficult, in the last analysis, because it requires one to think for oneself. When a student writes a term paper or essay on southwestern Native American pottery, he or she can churn out a series of ‘facts’ gleaned from the standard textbooks. Such a list of facts, or more accurately a repetition of the textbooks’ narratives, may not get a particularly good mark in the absence of any critical analysis or independent thinking whatsoever, but the student will get by. Such an approach comes unstuck, however, in writing a theory essay. It’s more difficult to regurgitate things copied out of books and not really deeply understood when one is dealing with abstract ideas, particularly when one writer disagrees so clearly and fundamentally with another. Though any crop of undergraduate essays will demonstrate that it is not impossible.

The literary theorist Jonathan Culler (1997, 16–17) points out that:

theory makes you desire mastery: you hope that theoretical reading will give you the concepts to organize and understand the phenomena that concern you. But theory makes mastery impossible, not only because there is always more to know, but, more specifically and more painfully, because theory is itself the questioning of presumed results and the assumptions on which they are based.

Theory, then, involves pain. It involves the deliberate placing of oneself in a vulnerable position, where the need to think for oneself makes one’s conclusions always provisional and always open to attack from others.

Thinking for oneself, however, is something every student of archaeology (or any other critical discipline for that matter) is (or should be) in the business of doing. Ultimately, critical evaluation with reference to evidence is the key-stone of a liberal education. In an age when education is increasingly seen as a commodity, in which knowledge can, it is implied, be bought and sold in the marketplace, the idea of an education as learning the skills of thinking critically and of evaluating the evidence for and against a particular view is more and more under attack. Perhaps it is this cultural context that has led to some of the sharpness of the ritualized denunciations of theory.

Understanding Theory

Well, I still feel pretty dubious about theory, but I’m prepared togo along with you for a bit. Where do we go from here?

The rest of this book will try to illuminate some of the major trends in archaeological theory, starting with the 1960s and moving on from there. To try to make this book as clear as possible, I am going to adopt two strategies.

First, from time to time I shall talk at length about developments in associated disciplines and in intellectual thought as a whole. As a result, long passages and even sub-sections of chapters may seem utterly irrelevant to the practising archaeologist. The reason I do this is because archaeology has had a habit of picking up ideas second-hand from other disciplines. Ideas have been changed, even confused and distorted, in the process. As a result, it is necessary to go back ‘to source’ to explain them clearly and to understand precisely how they have been used and abused by archaeologists. So please bear with the text, plod through the ‘irrelevant’ material, and I will then try to explain its relevance to archaeological thought.

Second, I shall look at the development of theory historically, looking first at the origins of the New Archaeology, then at reactions to it. I suggest that by understanding the historical context of a set of ideas such as ‘New Archaeology’ or ‘postprocessual archaeology’, one may more easily sympathize with its aims and grasp some of its underlying principles and concerns. By understanding this context we can also put many of the features of contemporary archaeology in their historical surroundings rather than place them in a vacuum.

The next chapter will discuss the New Archaeology; the following three will look at the questions of ‘science’ and ‘anthropology’ that it raised. The New Archaeology is now over 40 years old, but the intellectual questions raised by New Archaeologists are, I will suggest, absolutely central to contemporary archaeological theory and practice.

2

The ‘New Archaeology’

Most archaeologists fall in love with the subject by getting ‘hooked’ on things. The things vary from case to case – castles, Roman baths, flint or chert arrowheads, Neolithic pots, Maya temples – but in most cases the immediate appeal is of mystery and romance, of the past calling to us through its remains. This romantic appeal is often aesthetic and sensual as well as intellectual. Archaeologists love clambering round medieval ruins or handling pottery sherds. We try to persuade ourselves, however, that these ruins or sherds are mere ‘data’. (One colleague told me that as a result of the acute boredom of his researches he now loathes Neolithic pottery to the depths of his soul, but I interpret this as another, rather twisted form of love.) Artefacts, whether as small as an arrowhead or as large as a royal palace, fascinate us.

This love of artefacts, in itself, has nothing to do with archaeology in the strict sense as the study of the past. Artefacts tell us nothing about the past in themselves. I have stood in the middle of countless ruins of castles and ancient palaces and listened very carefully, and not heard a single syllable. Colleagues tell me that they have had similar distressing experiences with pottery, bones, bags of seeds. They love handling and experiencing their material, but it remains silent. In and of itself, it tells them precisely nothing.

Artefacts can’t tell us anything about the past because the past does not exist. We cannot touch the past, see it or feel it; it is utterly dead and gone. Our beloved artefacts actually belong to the present. They exist in the here and now. They may or may not have been made and used by real people thousands of years ago, but our assessment of the date of their manufacture and use is itself an assessment that we make, that is made in the present.

Until scientists invent a time machine, the past exists only in the things wesay about it. Archaeologists choose to ask certain questions of our material: ‘How many beads were found in this grave?’ ‘Do we see a shift to intensive exploitation of llamas in the Formative Period?’ ‘What was it like to live in the Bronze Age?’ ‘What degree of social inequality do we see in this period?’ We make general or particular statements about the past: ‘There was increased use of obsidian in Phase 3B of this site’; ‘There were more elements of cultural continuity between Mesolithic and Neolithic populations than have hitherto been assumed’; ‘Gender relations became less equal through time’; ‘The Romans were a cruel and vicious people’. These are all statements made here, now, in the present, as I write and you read. They do not belong to the past.

It is only in works of fiction, or if you believe in ghosts, that past and present can really be made to collide and merge into each other. It is striking that many writers have used this collision with great effect to disturb and horrify the ‘rational’ Western mind (the novels of Peter Ackroyd are excellent examples of this). More critically, this collision of past and present is also possible within ‘non-Western’ schemes of thought, where living cultural traditions may be held to be embodiments of cultural memory and in which past and present are not so radically divided; hence in part the conflicts between different cultures over, for example, excavation and reburial of Native American human remains, where the belief that time moves in a cycle rather than in a line makes archaeological excavation a threat to the present through its ‘desecration’ of the past. ‘Indigenous archaeology’ does not, then, necessarily make this radical division between present and past, a point we will return to in chapter 12.

Now it is the task of archaeologists to find out about the past. We want to know what really happened back then. The source materials – stones, bones, pots – are in the present, and the past that we create is also in the present. We will never ‘know’ what the past was ‘really like’, but we all can and do try to write the ‘best’ account we can, an account that is informed by the evidence that we have and that tries to be coherent and satisfying to us.

One of the basic problems of archaeology, then, is summarized in figure 2.1. Somehow we have to take the archaeological materials that we have and through our questioning get them to give us information about the past. There is a gulf between past and present, a gulf that the archaeologist has to bridge somehow even if it can never be bridged securely or definitively. Otherwise we risk a descent into the mindless activity of simply assembling and collating old objects for their own sake, rather than as evidence for the past (an activity which has been derided as ‘mere antiquarianism’, though such a term fails to do justice to the methods of early antiquarians).

I am labouring this point because it is easy to fall into the trap of believing that the very physicality of archaeological material will in itself tell us what the past was like. It will not. Kick a megalith and it hurts; stand in a castle chamber and you see nothing but medieval fabric. But kicking the megalith or standing in that cold chamber will tell you nothing about what the Neolithic or the Middle Ages were ‘really like’, or what processes led to the construction and use of the megalith or castle. Archaeologists only see megalith and castle in the present, the here and now. This is a present that is framed by contemporary ideas, attitudes and assumptions. We see megalith and castle through our eyes, not the eyes of the prehistoric or medieval observer.

Figure 2.1 The gulf between present and past