1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In "Astoria; Or, Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains," Washington Irving presents a richly detailed narrative chronicling the early 19th-century fur trade in the Pacific Northwest. This work blends travel writing with historical accounts, employing an engaging literary style that combines wit, pathos, and vivid descriptions of the American landscape. Irving meticulously documents the ambitious ventures of John Jacob Astor and his company's attempts to establish a commercial outpost in uncharted territories, exploring themes of exploration, commerce, and the rugged individualism of frontier life. The book emerges as a significant contribution to American literature, framed within the broader context of Manifest Destiny and the spirit of adventure that characterized the era. Washington Irving, a pivotal figure in American literature, is renowned for his ability to weave narratives that reflect the complexities of his time. His experiences in early 19th-century America'—including his travels, exposure to diverse cultures, and keen observations'—shaped his perspective on the burgeoning nation. These insights, alongside his nuanced understanding of human nature, culminate in this endeavor, where Irving manages to capture both the grand vision and the intimate anecdotes of those pursuing the American dream. "Astoria" is highly recommended for readers interested in the history of American exploration and the intricate tapestry of cultural encounters in the early United States. Irving's masterful storytelling not only entertains but also imparts valuable lessons about ambition, resilience, and the nature of pioneering spirit. This book is an essential read for scholars, history enthusiasts, and anyone captivated by the timeless allure of adventure. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - An Author Biography reveals milestones in the author's life, illuminating the personal insights behind the text. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Astoria; Or, Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains

Table of Contents

Introduction

Across wind-scoured mountains and along storm-bitten coasts, Astoria captures how a daring commercial gamble collides with the vastness of a continent and the limits of human resolve.

Astoria; Or, Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains is Washington Irving’s expansive narrative history of a bold American venture to the Pacific Northwest, written in the mid-1830s and first published in 1836. Best known for his sketches and tales, Irving here turns to documentary storytelling, recounting an ambitious attempt to extend trade across the continent. Without divulging outcomes, he presents the endeavor’s conception, its logistical intricacies, and the human dramas that accompany a hazardous push beyond familiar horizons. His purpose is at once historical and literary: to assemble scattered records into a lucid, compelling account that illuminates an inflection point in American expansion.

Irving undertook the project with special access to company papers, journals, and correspondence, allowing him to weave firsthand observations into a continuous, readable chronicle. The enterprise he narrates was initiated by the prominent merchant John Jacob Astor, whose materials and perspective informed the work. Irving’s method was not that of a field reporter but of a synthesizer and stylist: he listened to participants, studied their records, and arranged their experiences into episodes that highlight risks, strategies, misunderstandings, and the sheer labor of traversing an unmapped interior. The result is a narrative that balances documentary care with the pacing and texture of literature.

Astoria forms part of Irving’s late-career engagement with Western subjects, alongside A Tour on the Prairies (1835) and The Adventures of Captain Bonneville (1837). Having returned to the United States after years abroad, he turned his polished prose toward American scenes, seeking to reconcile national myth with factual record. In Astoria he tests how far elegance can carry history without sacrificing accuracy, and how far archival fidelity can sustain drama without invention. The book exemplifies his ambition to give American readers a history that feels lived-in, yet scrupulous, linking distant coasts, river systems, and trading posts into a coherent continental vision.

Its classic status rests first on scope. Few earlier American works attempted such a panoramic account of the Pacific Northwest, its river corridors, and the vast logistical chain tying Atlantic markets to Pacific possibilities. Irving shows how enterprise moves through weather, terrain, supply lines, and human networks, creating an early literary map of a region that would loom large in national imagination. By treating trade as a theater of character and chance, he dignifies the practical with narrative resonance, helping later readers and writers recognize commerce, rather than solely conquest, as a central engine of frontier transformation.

Astoria is also classic for the form it refines: the narrative history that reads with the clarity of a novel while maintaining documentary restraint. Irving’s graceful synthesis demonstrated that American materials—journals, ledgers, diplomatic entanglements, and campfire recollections—could be shaped into a story engaging enough for general audiences without betraying the record. This approach set expectations for subsequent chronicles of exploration and travel writing throughout the nineteenth century. In literary history, the book bridges polished Eastern letters and rough Western subject matter, proving that the nation’s emerging frontiers could be rendered with stylistic poise and interpretive tact.

At its core, the book follows a twofold plan to establish a commercial foothold on the far coast: one route by sea, the other overland across the continent. This premise furnishes Irving with intersecting lines of movement, contrasting the hazards and calculations of ships traversing remote waters with the trials of parties threading mountain passes and great river valleys. He attends to provisioning, leadership, and the unpredictable alchemy of weather, terrain, and personality. Without foreshadowing outcomes, the narrative emphasizes the ambition required to stitch together far-flung operations at a time when news traveled slowly and decisions carried irrevocable weight.

Throughout, Irving explores themes that have secured the book’s endurance: the magnetism of profit and the perils of overreach; the friction between planning and chance; and the moral and practical complexity of encounters among traders, trappers, and Indigenous nations. He is attentive to how reputation, rumor, and the scarcity of reliable information shape judgment in the field. The natural world appears not as passive backdrop but as active constraint, demanding improvisation and humility. In tracing these currents, the book examines the thin line separating vision from hubris and shows how collective endeavors hinge on courage, caution, and mutual dependence.

The work’s artistry lies in its arrangement. Irving favors anecdote and character sketch, but he never loses sight of the larger machinery: ships and stores, routes and rendezvous, rival companies and contested claims. His prose, urbane yet unforced, confers rhythm and lucidity on complex events, keeping the reader oriented while allowing for suspense and surprise. The narrative cadence alternates between panoramic surveys and intimate moments of decision, a structure that underscores how history is made in both boardrooms and bivouacs. That interplay gives Astoria its distinctive blend of breadth and immediacy.

Astoria inhabits the early nineteenth century, when global trade connected Atlantic cities with Pacific harbors and interior river systems served as arteries of exchange. Irving’s account reflects the geopolitical crosscurrents of the era and the layered sovereignties of the continent’s interior, where negotiation was as crucial as navigation. Modern readers will recognize that the book bears the assumptions of its time; yet precisely because it preserves period perspectives, it offers a valuable window onto contemporary understandings of territory, commerce, and cultural contact. Reading it critically enhances its historical value and enriches its narrative pleasures.

The book continues to resonate for its portrait of enterprise under uncertainty. Today’s readers, accustomed to global supply chains and rapid communication, can find in Irving’s pages a study of coordination when distances were vast and information scarce. Its attention to leadership, logistics, and stakeholder interests feels strikingly modern, while its depiction of environmental hazard and cross-cultural encounter prompts reflection on responsibility and restraint. The narrative reminds us that ambition always meets realities not of its making and that success depends on adaptability as much as on design, a lesson as pertinent in boardrooms as on backcountry trails.

In sum, Astoria endures because it melds documentary rigor with narrative grace, presenting an audacious commercial vision tested by landscape, weather, and human character. It invites readers to consider themes of risk, cooperation, and moral complexity while charting an episode central to the nation’s western horizons. Irving’s craftsmanship and judicious pacing keep the story vivid without sensationalism, making the book both instructive and absorbing. Its lasting appeal lies in this equilibrium: it satisfies curiosity about how such enterprises were conceived and carried out, and it challenges us to measure ambition against its costs, a balance that remains timelessly compelling.

Synopsis

Astoria; Or, Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains recounts the early nineteenth-century attempt, led by John Jacob Astor, to establish a permanent American fur-trading post on the Pacific coast. Washington Irving assembles the narrative from company papers, journals, and interviews, presenting a documentary history of the Pacific Fur Company. The book sketches the geopolitical landscape of the North American fur trade, noting competition with British-Canadian firms and the commercial promise of the Columbia River basin. It situates the venture within expanding global markets, where furs would move from interior tribes to the Pacific, then to China, while imported goods would return to the United States, forming a transcontinental circuit.

Irving outlines Astor’s integrated plan: a seaborne arm to carry men, supplies, and trade goods to the Columbia, and an overland expedition to establish interior connections and a reliable route. Former employees of the North West Company were recruited as partners and clerks, including Duncan McDougall, David Stuart, Donald McKenzie, and others. The ship Tonquin, under Captain Jonathan Thorn, would found the post at the river’s mouth, while Wilson Price Hunt led the inland party from St. Louis. The narrative describes organizational details, contracts, and the careful balancing of commercial aims with the practical challenges of distance, climate, and uncertain alliances in a contested frontier.

The Tonquin’s voyage forms the book’s first major movement. Departing New York, the vessel rounds Cape Horn, stops in the Hawaiian Islands to hire skilled canoe men and interpreters, and approaches the formidable bar of the Columbia River. Irving narrates the hazardous entry and the subsequent establishment of Fort Astoria. Early trade with coastal peoples develops amid mutual assessment, as the post’s leaders learn local protocols and seasonal patterns of movement and exchange. Leadership tensions aboard ship, particularly Captain Thorn’s strict discipline, carry into shore operations. The account emphasizes logistical tasks—building, provisioning, and coastal surveying—while noting the international visibility of the nascent settlement.

Parallel to the maritime effort, Hunt’s overland expedition advances from St. Louis with a mixed company of American frontiersmen, French Canadian voyageurs, and Indigenous guides and families. Irving describes the ascent of the Missouri, negotiations with Plains communities, and the onset of winter near the Arikara villages. In spring, the party turns west through rough country toward the headwaters feeding the Snake and Columbia. Supply shortages, terrain difficulties, and divergent opinions about the best route lead to divisions into smaller groups. The narrative records river hazards, the limits of existing maps, and the importance of local knowledge in navigating high plains, mountains, and interlaced watersheds.

Back on the coast, the Tonquin sails north to expand trade relations. Irving relates a fraught encounter that escalates during a trading visit, culminating in the ship’s loss and the death of most of those aboard. The episode underscores the volatility of maritime exchange when expectations are mismatched and trust breaks down. Its immediate consequence is the curtailment of coastal trading capacity and a reduction in experienced personnel available to Astoria. The narrative notes the impact on morale and the tightening of security at the fort, while also emphasizing the broader lesson for the enterprise: that distant outposts rely on steady, respectful relations and consistent supply lines to maintain stability.

The inland story resumes with separated parties struggling through the Snake River country, forced by hunger and river accidents to adopt improvised strategies. Irving chronicles raft failures, foraging, and assistance received along the way. Survivors reach Astoria over time, bringing intelligence about interior routes and communities. Relief arrives by sea when the Beaver reaches the fort, replenishing goods and carrying company partners to Russian posts in Alaska to negotiate supplementary supplies. These maritime-diplomatic exchanges broaden the enterprise’s network but also illustrate its vulnerability to timing, weather, and competing priorities. Meanwhile, the overland experiences expand geographic understanding, mapping practical passes and seasonal constraints.

Into this fragile equilibrium comes the War of 1812. Irving details how news of hostilities with Britain alters calculations for an American outpost on a coast patrolled by British ships and frequented by British-Canadian traders. The North West Company advances overland, and negotiations begin with Astoria’s leadership. Before a British warship arrives, company agents agree to transfer Pacific Fur Company assets and inventories to the North West Company. Later, a British naval vessel formally takes possession and renames the post, confirming a change long underway. The book presents documents and testimonies explaining the decision as a commercial mitigation of wartime risk rather than a contested military event.

Irving follows the return journeys and aftermath. Robert Stuart leads a small party eastward, identifying a broad, workable passage later known as South Pass, a key corridor for subsequent overland migrations. The narrative summarizes the fates of various participants, the dispersal of company assets, and the consolidation of the fur trade under rival firms. Irving includes descriptions of landscapes, river systems, and observations on diverse Indigenous nations encountered, noting languages, trade practices, and diplomacy, though reflecting the era’s documentary perspective. The cumulative record provides geographic and logistical knowledge valuable for later travelers, even as the original commercial design concludes under the pressures of war and competition.

The book’s overarching message is a measured portrait of ambition meeting environment, distance, and geopolitics. Astor’s design seeks to link continental interior resources with global markets, but success depends on coordinated sea and land operations, dependable supply, and sustained local relationships. Irving’s narrative shows how natural barriers, leadership decisions, rival enterprises, and international conflict shaped outcomes. Astoria stands as an early American attempt to anchor a Pacific presence through trade rather than conquest. While the enterprise does not endure as planned, its routes, observations, and experiences contribute to knowledge of the West and demonstrate the interdependence of commerce, geography, and diplomacy in continental expansion.

Historical Context

Astoria; Or, Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains is set chiefly between 1810 and 1813, when American and British commercial empires pushed into the Columbia River basin after the Louisiana Purchase (1803). The narrative centers on the lower Columbia, at the river’s mouth in present-day Oregon, where Fort Astoria rose as a coastal hub linking interior beaver streams to the Pacific world. Its stage stretches across New York mercantile houses, St. Louis gateways, the Rocky Mountains, and Pacific ports from Sitka to Canton (Guangzhou). The book unfolds in a contested region claimed in varying degrees by the United States, Britain, Spain, and Russia.

Washington Irving’s account inhabits a world shaped by the fur trade’s global circuits and by diplomatic ambiguity along the Northwest Coast. The time was marked by the aftershocks of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806) and by the looming War of 1812, which tightened British naval control of sea lanes. Indigenous polities—Chinookan, Clatsop, Kathlamet, and upriver nations at The Dalles—organized commerce and diplomacy on the Columbia, while Montreal’s North West Company (NWC) pressed south from the interior. Irving situates the endeavor within a precarious confluence of transoceanic trade, inter-imperial rivalry, and fragile overland logistics in an unmapped continental interior.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806), commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson, charted routes from St. Louis to the Pacific, wintering at Fort Clatsop (1805–1806) near the Columbia’s mouth. The expedition produced maps, ethnographic notes, and river intelligence that informed later American ventures. By reporting navigability, resource potential, and geographic obstacles, it offered the most comprehensive U.S. knowledge of the Northwest. Astoria directly leverages this legacy: Irving shows how John Jacob Astor planned his enterprise with the Corps of Discovery’s cartographic and logistical lessons in mind, viewing the Columbia as a gateway for an American transcontinental trade corridor to the Pacific.

John Jacob Astor founded the American Fur Company in 1808 and, to project U.S. commerce to the Pacific, organized the Pacific Fur Company (PFC) in 1810. He recruited partners such as Wilson Price Hunt, Duncan McDougall, Donald McKenzie, Robert Stuart, Alexander McKay, and Ramsay Crooks. The plan combined a maritime arm—led initially by the ship Tonquin—to establish a coastal depot, with an overland arm from St. Louis to supply the interior. Fort Astoria was erected in spring 1811 as the first American-owned settlement on the Pacific coast. Irving’s narrative, commissioned by Astor and based on partner journals, chronicles the company’s formation and early operations.

The maritime fur and China trade, active since the 1780s, linked the Northwest Coast to Canton (Guangzhou). American and British ships exchanged sea otter and beaver pelts for tea, silk, and porcelain under the Qing-era Cohong system. Astor’s scheme envisioned furs collected at Astoria being shipped aboard vessels like the Beaver to China, with Asian goods returning to New York for U.S. markets. This triangular commerce relied on predictable sea lanes and neutrality. Irving details the prices, cargoes, and ports, showing how Astor sought to exploit gaps left by the waning Spanish presence and to compete with the British East India Company’s commercial networks.

The overland expedition led by Wilson Price Hunt departed St. Louis in April 1811, moving up the Missouri through Arikara country, then across the Platte and into the Snake River basin. Lacking canoes suited to the treacherous Snake, the party suffered severe privations, starvation, and fragmentation in winter 1811–1812 before straggling to the Columbia and reaching Fort Astoria early in 1812. Figures like Donald McKenzie and Robert Stuart later undertook interior forays and return missions. Irving reconstructs the route, the ethnographic encounters, and the survival ordeals from journals by Gabriel Franchère and others, turning logistical crises into a central explanatory thread of the enterprise’s vulnerability.

The Tonquin incident (June 1811) occurred at Clayoquot Sound on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Under Captain Jonathan Thorn, the ship engaged in tense bargaining with Tla-o-qui-aht people; after Thorn reportedly insulted local leaders, a violent confrontation ensued. Most of the crew was killed, and the ship subsequently exploded—likely scuttled by a wounded sailor—leaving one or two survivors. The loss erased a key maritime asset and poisoned regional relations. Irving recounts the episode as a cautionary tale about cultural ignorance, rigid naval discipline, and the hazards of coastal trade, showing how a single misjudgment could cripple an entire commercial strategy.

The North West Company (NWC), headquartered in Montreal, intensified competition across the interior. David Thompson, its astronomer-surveyor, established posts such as Spokane House (1810) and descended the Columbia in July 1811, planting British claims at key confluences before visiting the newly founded Astoria. NWC brigades, led by partners including John George McTavish, controlled transport routes from the Great Lakes to the Rockies, drawing on extensive Indigenous partnerships. Irving portrays the rival company’s reach and cohesion as structural advantages over the nascent PFC, emphasizing encounters between Astorians and NWC men that foreshadowed the eventual commercial and legal struggle for the Columbia basin.

The War of 1812, declared by the United States in June 1812, reshaped Pacific operations. British naval superiority tightened blockades, menacing American shipping and insurance. Orders in Council, impressment, and frontier conflicts framed the transatlantic causes, but the Columbia theater turned on logistics. Without secure resupply, the PFC’s coastal depot and inland posts faced shortages and isolation. Irving highlights the war’s geopolitical shock: a private American venture suddenly became entangled in imperial conflict, with British authorities and Canadian traders gaining leverage via protected supply lines. The war’s onset transformed Astor’s calculated risk into a precarious wager on distant seas and mountain corridors.

Maritime disruptions devastated Astor’s timetable. The Beaver reached Sitka (Novo-Arkhangelsk) in 1812 to trade with the Russian-American Company under Alexander Baranov, then sailed to Canton as war news spread. The relief ship Lark, dispatched in 1813, wrecked in the Hawaiian Islands, eliminating a crucial lifeline. British licenses and NWC transport networks from Montreal and Fort William allowed rivals to maintain field capacity, while American neutrality evaporated. Irving follows these cascading failures—missed rendezvous, stranded inventories, and unanswered letters—to show how global war translated into shortages at Astoria, demoralized partners, and emboldened competitors who could reach the Columbia faster and with official protection.

By October 1813, Duncan McDougall and other PFC partners—assessing capture risk—sold Fort Astoria’s assets to John George McTavish of the NWC. When HMS Racoon arrived in December 1813, the post was renamed Fort George under the Union Jack. The Treaty of Ghent (December 1814) stipulated restoration of places taken during the war, but practical possession remained with the NWC, and after 1818 the United States and Britain agreed to joint occupation of the Oregon Country. Irving frames these events as the enterprise’s denouement: diplomacy lagged behind facts on the ground, and private capital proved brittle against naval power and imperial logistics.

Indigenous trade networks along the lower Columbia predated American arrival by centuries, organizing exchange in salmon, wapato, obsidian, and coastal goods. Chinookan leaders such as Comcomly acted as diplomatic brokers, controlling river mouths and portage knowledge; The Dalles functioned as an upriver emporium for Wasco-Wishram and Plateau peoples. Epidemics like smallpox had already disrupted demography in the late eighteenth century, yet commerce persisted through kin ties and ceremonial protocols. Irving’s narrative records negotiations, gift-giving, and misunderstandings, illustrating how Astorians depended on local pilots, food, and alliances. The book reflects a political landscape in which Indigenous sovereignty shaped access and survival.

Robert Stuart’s 1812–1813 eastbound journey discovered South Pass, a broad, low crossing of the Continental Divide in present-day Wyoming. His small party, carrying post papers, traversed the Sweetwater and Platte and reached St. Louis in April 1813. This route became the backbone of the overland Oregon Trail in the 1830s–1840s, enabling wagons and large-scale migration to the Pacific Northwest. Irving emphasizes the discovery’s strategic importance: even as the Astoria venture faltered, it yielded geographic intelligence that altered continental mobility and future U.S. settlement patterns, strengthening American claims to the Columbia basin by transforming a forbidding barrier into an accessible corridor.

The Nootka Conventions (1790–1794) between Britain and Spain resolved the Nootka Crisis, ending Spain’s attempt at exclusive control over the Northwest Coast and allowing multiple nations to navigate and trade there. This legal backdrop fostered competitive access for British, American, and Russian merchants, accelerating the maritime fur trade that supplied Canton. Irving situates Astor’s project within this framework of shared rights and ambiguous sovereignty, noting that the absence of a single enforcing power created both opportunity and peril. The conventions’ legacy explains the legal uncertainty at Astoria and the fluidity with which flags, claims, and commercial privileges shifted in the region.

Russian America, administered by the Russian-American Company from bases such as Sitka after 1804, sought foodstuffs and trade goods in exchange for furs harvested by Native Alaskan labor. Governor Alexander Baranov cultivated pragmatic ties with foreign merchants. Astor intended to supply Russian posts and funnel pelts to China via the Beaver, integrating the Columbia into a triangular network linking New York, Alaska, and Canton. War and distance destabilized this plan. Irving’s narrative of negotiations at Sitka and missed opportunities emphasizes how multinational entanglements—Russian needs, British policy, Qing trade rules—could either scaffold or collapse a private American venture on the Pacific rim.

Astoria functions as a critique of the era’s fusion of private capital and imperial strategy. Irving exposes how state power—naval blockades, licensing, and diplomatic delay—determined outcomes more than entrepreneurial daring. He contrasts Astor’s vast New York capital with the precarious lives of clerks, voyageurs, and sailors, whose labor and risk underwrote speculative profits. Episodes like Captain Thorn’s authoritarian conduct on the Tonquin illuminate the costs of rigid hierarchy and cultural contempt. The book highlights a political economy in which monopolies, charters, and informal empire structured markets, rendering “free enterprise” contingent on unequal access to coercion and international protection.

The narrative also critiques social injustice toward Indigenous nations whose sovereignty and systems of exchange were overridden by extractive commerce. Irving records negotiations and gifts, yet shows how misunderstanding, disease, and opportunism eroded reciprocal ties. The sale of Astoria under duress and the easy renaming to Fort George display the disposability of local communities in imperial contests. By chronicling starvation marches, shipboard violence, and speculative overreach, the book interrogates class divides between metropolitan financiers and frontier laborers. It thereby exposes a broader early nineteenth-century issue: the transformation of contested homelands into commercial corridors shaped by distant political decisions.

Author Biography

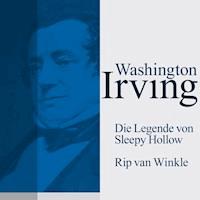

Washington Irving (1783–1859) was an American author, essayist, and diplomat whose work helped define early national literature in the United States. Active from the early nineteenth century through midcentury, he is widely credited as one of the first American writers to gain sustained international readership. Writing under personae such as Geoffrey Crayon and Diedrich Knickerbocker, he blended urbane humor, folklore, and travel sketch into forms that appealed on both sides of the Atlantic. His tales “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” together with a body of essays and histories, established models for the short story, the familiar essay, and the literary sketch in America.

Born in New York City, Irving studied law and was admitted to the bar, though he practiced only briefly. As a young man he contributed light pieces to newspapers under the signature Jonathan Oldstyle and helped launch the satirical periodical Salmagundi, sharpening a comic style rooted in urban observation. His reading drew on British essayists such as Addison and Steele, the sentimental and picturesque modes of Oliver Goldsmith, and emerging Romantic interests in landscape and legend. Early travels in Europe broadened his perspective and connected him to transatlantic literary circles, a context that would inform his experiments with pseudonymous narration and gently ironic social commentary.

Irving’s first major success came with A History of New York, purportedly authored by the eccentric antiquarian “Diedrich Knickerbocker.” This mock history, focused on Dutch-era New Amsterdam, mixed parody with affectionate local color and displayed his talent for creating narrators whose voices are as memorable as their subjects. The book’s playful footnotes, invented authorities, and comic digressions satirized pedantic historiography while also shaping a regional mythology for New York. Its popularity gave lasting currency to the Knickerbocker persona, which later became shorthand for a broader New York cultural identity. The work established Irving as a leading humorist and secured a readership ready for his more cosmopolitan sketches.

International fame followed with The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., a collection of essays and tales written largely during a prolonged stay in Britain. Its mixture of travel impressions, holiday pieces, and two enduring American tales—“Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”—demonstrated his skill at weaving Old World forms with New World settings and folklore. Encouraged by friendships with prominent British writers, including Sir Walter Scott, he refined a polished prose manner attentive to atmosphere and scene. The Sketch Book was warmly received in the United States and Britain, helping to validate an American author in transatlantic markets without surrendering national character.

He extended this success with Bracebridge Hall and Tales of a Traveller, continuing the persona of Geoffrey Crayon. Residence in Spain deepened his historical interests. Working with materials in Madrid, he produced A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, the Chronicle of the Conquest of Granada, and Legends of the Conquest of Spain, works that combined archival research with narrative grace. The Alhambra, a collection of sketches and tales set around the Moorish palace, offered romantic evocations of place alongside retellings of local legends. Irving also wrote a biography of Oliver Goldsmith, reflecting his admiration for eighteenth-century models that had shaped his own style.

Irving alternated literary production with public service. In the late 1820s and early 1830s he worked in American diplomatic posts in Madrid and London, experience that reinforced his role as a cultural intermediary. After returning to New York, he settled along the Hudson River and wrote Astoria, a commissioned narrative of the Pacific Northwest fur trade, and The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, adapted from frontier journals. In the early 1840s he served as United States minister to Spain, then devoted his final major effort to the multivolume Life of George Washington. That undertaking consolidated decades of research and presented a dignified, readable portrait of the nation’s founding leader.

In his later years Irving lived at Sunnyside on the Hudson River, receiving visitors and continuing to revise and collect his writings. He died in the mid-nineteenth century, by then an emblem of American letters whose career modeled professional authorship supported by a broad reading public. His genial irony, picturesque description, and deft handling of folklore have kept key tales in circulation, while his essays and historical narratives remain valued for style and narrative poise. Scholars now read him as a bridge figure linking British and American traditions, and general readers encounter him as a storyteller whose images still shape the cultural memory of early America.

Astoria; Or, Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains

CHAPTER I.

TWO leading objects of commercial gain have given birth to wide and daring enterprise in the early history of the Americas; the precious metals of the South, and the rich peltries of the North. While the fiery and magnificent Spaniard, inflamed with the mania for gold, has extended his discoveries and conquests over those brilliant countries scorched by the ardent sun of the tropics, the adroit and buoyant Frenchman, and the cool and calculating Briton, have pursued the less splendid, but no less lucrative, traffic in furs amidst the hyperborean regions of the Canadas, until they have advanced even within the Arctic Circle.

These two pursuits have thus in a manner been the pioneers and precursors of civilization.[1q] Without pausing on the borders, they have penetrated at once, in defiance of difficulties and dangers, to the heart of savage countries: laying open the hidden secrets of the wilderness; leading the way to remote regions of beauty and fertility that might have remained unexplored for ages, and beckoning after them the slow and pausing steps of agriculture and civilization.

It was the fur trade, in fact, which gave early sustenance and vitality to the great Canadian provinces. Being destitute of the precious metals, at that time the leading objects of American enterprise, they were long neglected by the parent country. The French adventurers, however, who had settled on the banks of the St. Lawrence, soon found that in the rich peltries of the interior, they had sources of wealth that might almost rival the mines of Mexico and Peru. The Indians, as yet unacquainted with the artificial value given to some descriptions of furs, in civilized life, brought quantities of the most precious kinds and bartered them away for European trinkets and cheap commodities. Immense profits were thus made by the early traders, and the traffic was pursued with avidity.

As the valuable furs soon became scarce in the neighborhood of the settlements, the Indians of the vicinity were stimulated to take a wider range in their hunting expeditions; they were generally accompanied on these expeditions by some of the traders or their dependents, who shared in the toils and perils of the chase, and at the same time made themselves acquainted with the best hunting and trapping grounds, and with the remote tribes, whom they encouraged to bring their peltries to the settlements. In this way the trade augmented, and was drawn from remote quarters to Montreal. Every now and then a large body of Ottawas, Hurons, and other tribes who hunted the countries bordering on the great lakes, would come down in a squadron of light canoes, laden with beaver skins, and other spoils of their year’s hunting. The canoes would be unladen, taken on shore, and their contents disposed in order. A camp of birch bark would be pitched outside of the town, and a kind of primitive fair opened with that grave ceremonial so dear to the Indians. An audience would be demanded of the governor-general, who would hold the conference with becoming state, seated in an elbow-chair, with the Indians ranged in semicircles before him, seated on the ground, and silently smoking their pipes. Speeches would be made, presents exchanged, and the audience would break up in universal good humor.

Now would ensue a brisk traffic with the merchants, and all Montreal would be alive with naked Indians running from shop to shop, bargaining for arms, kettles, knives, axes, blankets, bright-colored cloths, and other articles of use or fancy; upon all which, says an old French writer, the merchants were sure to clear at least two hundred per cent. There was no money used in this traffic, and, after a time, all payment in spirituous liquors was prohibited, in consequence of the frantic and frightful excesses and bloody brawls which they were apt to occasion.

Their wants and caprices being supplied, they would take leave of the governor, strike their tents, launch their canoes, and ply their way up the Ottawa to the lakes.

A new and anomalous class of men gradually grew out of this trade. These were called coureurs des bois[1], rangers of the woods; originally men who had accompanied the Indians in their hunting expeditions, and made themselves acquainted with remote tracts and tribes; and who now became, as it were, peddlers of the wilderness. These men would set out from Montreal with canoes well stocked with goods, with arms and ammunition, and would make their way up the mazy and wandering rivers that interlace the vast forests of the Canadas, coasting the most remote lakes, and creating new wants and habitudes among the natives. Sometimes they sojourned for months among them, assimilating to their tastes and habits with the happy facility of Frenchmen, adopting in some degree the Indian dress, and not unfrequently taking to themselves Indian wives.

Twelve, fifteen, eighteen months would often elapse without any tidings of them, when they would come sweeping their way down the Ottawa in full glee, their canoes laden down with packs of beaver skins. Now came their turn for revelry and extravagance. “You would be amazed,” says an old writer already quoted, “if you saw how lewd these peddlers are when they return; how they feast and game, and how prodigal they are, not only in their clothes, but upon their sweethearts. Such of them as are married have the wisdom to retire to their own houses; but the bachelors act just as an East Indiaman and pirates are wont to do; for they lavish, eat, drink, and play all away as long as the goods hold out; and when these are gone, they even sell their embroidery, their lace, and their clothes. This done, they are forced upon a new voyage for subsistence.”

Many of these coureurs des bois became so accustomed to the Indian mode of living, and the perfect freedom of the wilderness, that they lost relish for civilization, and identified themselves with the savages among whom they dwelt, or could only be distinguished from them by superior licentiousness. Their conduct and example gradually corrupted the natives, and impeded the works of the Catholic missionaries, who were at this time prosecuting their pious labors in the wilds of Canada.

To check these abuses, and to protect the fur trade from various irregularities practiced by these loose adventurers, an order was issued by the French government prohibiting all persons, on pain of death, from trading into the interior of the country without a license.

These licenses were granted in writing by the governor-general, and at first were given only to persons of respectability; to gentlemen of broken fortunes; to old officers of the army who had families to provide for; or to their widows. Each license permitted the fitting out of two large canoes with merchandise for the lakes, and no more than twenty-five licenses were to be issued in one year. By degrees, however, private licenses were also granted, and the number rapidly increased. Those who did not choose to fit out the expeditions themselves, were permitted to sell them to the merchants; these employed the coureurs des bois, or rangers of the woods, to undertake the long voyages on shares, and thus the abuses of the old system were revived and continued.

The pious missionaries employed by the Roman Catholic Church to convert the Indians, did everything in their power to counteract the profligacy caused and propagated by these men in the heart of the wilderness. The Catholic chapel might often be seen planted beside the trading house, and its spire surmounted by a cross, towering from the midst of an Indian village, on the banks of a river or a lake. The missions had often a beneficial effect on the simple sons of the forest, but had little power over the renegades from civilization.

At length it was found necessary to establish fortified posts at the confluence of the rivers and the lakes for the protection of the trade, and the restraint of these profligates of the wilderness. The most important of these was at Michilimackinac, situated at the strait of the same name, which connects Lakes Huron and Michigan. It became the great interior mart and place of deposit, and some of the regular merchants who prosecuted the trade in person, under their licenses, formed establishments here. This, too, was a rendezvous for the rangers of the woods, as well those who came up with goods from Montreal as those who returned with peltries from the interior. Here new expeditions were fitted out and took their departure for Lake Michigan and the Mississippi; Lake Superior and the Northwest; and here the peltries brought in return were embarked for Montreal.

The French merchant at his trading post, in these primitive days of Canada, was a kind of commercial patriarch. With the lax habits and easy familiarity of his race, he had a little world of self-indulgence and misrule around him. He had his clerks, canoe men, and retainers of all kinds, who lived with him on terms of perfect sociability, always calling him by his Christian name; he had his harem of Indian beauties, and his troop of halfbreed children; nor was there ever wanting a louting train of Indians, hanging about the establishment, eating and drinking at his expense in the intervals of their hunting expeditions.

The Canadian traders, for a long time, had troublesome competitors in the British merchants of New York, who inveigled the Indian hunters and the coureurs des bois to their posts, and traded with them on more favorable terms. A still more formidable opposition was organized in the Hudson’s Bay Company, chartered by Charles II., in 1670, with the exclusive privilege of establishing trading houses on the shores of that bay and its tributary rivers; a privilege which they have maintained to the present day. Between this British company and the French merchants of Canada, feuds and contests arose about alleged infringements of territorial limits, and acts of violence and bloodshed occurred between their agents.

In 1762, the French lost possession of Canada, and the trade fell principally into the hands of British subjects. For a time, however, it shrunk within narrow limits. The old coureurs des bois were broken up and dispersed, or, where they could be met with, were slow to accustom themselves to the habits and manners of their British employers. They missed the freedom, indulgence, and familiarity of the old French trading houses, and did not relish the sober exactness, reserve, and method of the new-comers. The British traders, too, were ignorant of the country, and distrustful of the natives. They had reason to be so. The treacherous and bloody affairs of Detroit and Michilimackinac showed them the lurking hostility cherished by the savages, who had too long been taught by the French to regard them as enemies.

It was not until the year 1766, that the trade regained its old channels; but it was then pursued with much avidity and emulation by individual merchants, and soon transcended its former bounds. Expeditions were fitted out by various persons from Montreal and Michilimackinac, and rivalships and jealousies of course ensued. The trade was injured by their artifices to outbid and undermine each other; the Indians were debauched by the sale of spirituous liquors, which had been prohibited under the French rule. Scenes of drunkeness, brutality, and brawl were the consequence, in the Indian villages and around the trading houses; while bloody feuds took place between rival trading parties when they happened to encounter each other in the lawless depths of the wilderness.

To put an end to these sordid and ruinous contentions, several of the principal merchants of Montreal entered into a partnership in the winter of 1783, which was augmented by amalgamation with a rival company in 1787. Thus was created the famous “Northwest Company[2],” which for a time held a lordly sway over the wintry lakes and boundless forests of the Canadas, almost equal to that of the East India Company over the voluptuous climes and magnificent realms of the Orient.

The company consisted of twenty-three shareholders, or partners, but held in its employ about two thousand persons as clerks, guides, interpreters, and “voyageurs,” or boatmen. These were distributed at various trading posts, established far and wide on the interior lakes and rivers, at immense distances from each other, and in the heart of trackless countries and savage tribes.

Several of the partners resided in Montreal and Quebec, to manage the main concerns of the company. These were called agents, and were personages of great weight and importance; the other partners took their stations at the interior posts, where they remained throughout the winter, to superintend the intercourse with the various tribes of Indians. They were thence called wintering partners.

The goods destined for this wide and wandering traffic were put up at the warehouses of the company in Montreal, and conveyed in batteaux, or boats and canoes, up the river Attawa, or Ottowa, which falls into the St. Lawrence near Montreal, and by other rivers and portages, to Lake Nipising, Lake Huron, Lake Superior, and thence, by several chains of great and small lakes, to Lake Winnipeg, Lake Athabasca, and the Great Slave Lake. This singular and beautiful system of internal seas, which renders an immense region of wilderness so accessible to the frail bark of the Indian or the trader, was studded by the remote posts of the company, where they carried on their traffic with the surrounding tribes.

The company, as we have shown, was at first a spontaneous association of merchants; but, after it had been regularly organized, admission into it became extremely difficult. A candidate had to enter, as it were, “before the mast,” to undergo a long probation, and to rise slowly by his merits and services. He began, at an early age, as a clerk, and served an apprenticeship of seven years, for which he received one hundred pounds sterling, was maintained at the expense of the company, and furnished with suitable clothing and equipments. His probation was generally passed at the interior trading posts; removed for years from civilized society, leading a life almost as wild and precarious as the savages around him; exposed to the severities of a northern winter, often suffering from a scarcity of food, and sometimes destitute for a long time of both bread and salt. When his apprenticeship had expired, he received a salary according to his deserts, varying from eighty to one hundred and sixty pounds sterling, and was now eligible to the great object of his ambition, a partnership in the company; though years might yet elapse before he attained to that enviable station.

Most of the clerks were young men of good families, from the Highlands of Scotland, characterized by the perseverance, thrift, and fidelity of their country, and fitted by their native hardihood to encounter the rigorous climate of the North, and to endure the trials and privations of their lot; though it must not be concealed that the constitutions of many of them became impaired by the hardships of the wilderness, and their stomachs injured by occasional famishing, and especially by the want of bread and salt. Now and then, at an interval of years, they were permitted to come down on a visit to the establishment at Montreal, to recruit their health, and to have a taste of civilized life; and these were brilliant spots in their existence.

As to the principal partners, or agents, who resided in Montreal and Quebec, they formed a kind of commercial aristocracy, living in lordly and hospitable style. Their posts, and the pleasures, dangers, adventures, and mishaps which they had shared together in their wild wood life, had linked them heartily to each other, so that they formed a convivial fraternity. Few travellers that have visited Canada some thirty years since, in the days of the M’Tavishes, the M’Gillivrays, the M’Kenzies, the Frobishers, and the other magnates of the Northwest, when the company was in all its glory, but must remember the round of feasting and revelry kept up among these hyperborean nabobs.

Sometimes one or two partners, recently from the interior posts, would make their appearance in New York, in the course of a tour of pleasure and curiosity. On these occasions there was a degree of magnificence of the purse about them, and a peculiar propensity to expenditure at the goldsmith’s and jeweler’s for rings, chains, brooches, necklaces, jeweled watches, and other rich trinkets, partly for their own wear, partly for presents to their female acquaintances; a gorgeous prodigality, such as was often to be noticed in former times in Southern planters and West India creoles, when flush with the profits of their plantations.

To behold the Northwest Company in all its state and grandeur, however, it was necessary to witness an annual gathering at the great interior place of conference established at Fort William, near what is called the Grand Portage, on Lake Superior. Here two or three of the leading partners from Montreal proceeded once a year to meet the partners from the various trading posts of the wilderness, to discuss the affairs of the company during the preceding year, and to arrange plans for the future.

On these occasions might be seen the change since the unceremonious times of the old French traders; now the aristocratic character of the Briton shone forth magnificently, or rather the feudal spirit of the Highlander. Every partner who had charge of an interior post, and a score of retainers at his Command, felt like the chieftain of a Highland clan, and was almost as important in the eyes of his dependents as of himself. To him a visit to the grand conference at Fort William was a most important event, and he repaired there as to a meeting of parliament.

The partners from Montreal, however, were the lords of the ascendant; coming from the midst of luxurious and ostentatious life, they quite eclipsed their compeers from the woods, whose forms and faces had been battered and hardened by hard living and hard service, and whose garments and equipments were all the worse for wear. Indeed, the partners from below considered the whole dignity of the company as represented in their persons, and conducted themselves in suitable style. They ascended the rivers in great state, like sovereigns making a progress: or rather like Highland chieftains navigating their subject lakes. They were wrapped in rich furs, their huge canoes freighted with every convenience and luxury, and manned by Canadian voyageurs, as obedient as Highland clansmen. They carried up with them cooks and bakers, together with delicacies of every kind, and abundance of choice wines for the banquets which attended this great convocation. Happy were they, too, if they could meet with some distinguished stranger; above all, some titled member of the British nobility, to accompany them on this stately occasion, and grace their high solemnities.

Fort William, the scene of this important annual meeting, was a considerable village on the banks of Lake Superior. Here, in an immense wooden building, was the great council hall, as also the banqueting chamber, decorated with Indian arms and accoutrements, and the trophies of the fur trade. The house swarmed at this time with traders and voyageurs, some from Montreal, bound to the interior posts; some from the interior posts, bound to Montreal. The councils were held in great state, for every member felt as if sitting in parliament, and every retainer and dependent looked up to the assemblage with awe, as to the House of Lords. There was a vast deal of solemn deliberation, and hard Scottish reasoning, with an occasional swell of pompous declamation.

These grave and weighty councils were alternated by huge feasts and revels, like some of the old feasts described in Highland castles. The tables in the great banqueting room groaned under the weight of game of all kinds; of venison from the woods, and fish from the lakes, with hunters’ delicacies, such as buffalos’ tongues, and beavers’ tails, and various luxuries from Montreal, all served up by experienced cooks brought for the purpose. There was no stint of generous wine, for it was a hard-drinking period, a time of loyal toasts, and bacchanalian songs, and brimming bumpers.

While the chiefs thus revelled in hall, and made the rafters resound with bursts of loyalty and old Scottish songs, chanted in voices cracked and sharpened by the northern blast, their merriment was echoed and prolonged by a mongrel legion of retainers, Canadian voyageurs, half-breeds, Indian hunters, and vagabond hangers-on who feasted sumptuously without on the crumbs that fell from their table, and made the welkin ring with old French ditties, mingled with Indian yelps and yellings.

Such was the Northwest Company in its powerful and prosperous days, when it held a kind of feudal sway over a vast domain of lake and forest. We are dwelling too long, perhaps, upon these individual pictures, endeared to us by the associations of early life, when, as yet a stripling youth, we have sat at the hospitable boards of the “mighty Northwesters,” the lords of the ascendant at Montreal, and gazed with wondering and inexperienced eye at the baronial wassailing, and listened with astonished ear to their tales of hardship and adventures. It is one object of our task, however, to present scenes of the rough life of the wilderness, and we are tempted to fix these few memorials of a transient state of things fast passing into oblivion; for the feudal state of Fort William is at an end, its council chamber is silent and deserted; its banquet hall no longer echoes to the burst of loyalty, or the “auld world” ditty; the lords of the lakes and forests have passed away; and the hospitable magnates of Montreal where are they?

CHAPTER II.

THE success of the Northwest Company stimulated further enterprise in this opening and apparently boundless field of profit. The traffic of that company lay principally in the high northern latitudes, while there were immense regions to the south and west, known to abound with valuable peltries[5]; but which, as yet, had been but little explored by the fur trader. A new association of British merchants was therefore formed, to prosecute the trade in this direction. The chief factory was established at the old emporium of Michilimackinac, from which place the association took its name, and was commonly called the Mackinaw Company[3].

While the Northwesters continued to push their enterprises into the hyperborean regions[6] from their stronghold at Fort William, and to hold almost sovereign sway over the tribes of the upper lakes and rivers, the Mackinaw Company sent forth their light perogues and barks, by Green Bay, Fox River, and the Wisconsin, to that areas artery of the West, the Mississippi; and down that stream to all its tributary rivers. In this way they hoped soon to monopolize the trade with all the tribes on the southern and western waters, and of those vast tracts comprised in ancient Louisiana.

The government of the United States began to view with a wary eye the growing influence thus acquired by combinations of foreigners, over the aboriginal tribes inhabiting its territories, and endeavored to counteract it. For this purpose, as early as 1796, the government sent out agents to establish rival trading houses on the frontier, so as to supply the wants of the Indians, to link their interests and feelings with those of the people of the United States, and to divert this important branch of trade into national channels.

The expedition, however, was unsuccessful, as most commercial expedients are prone to be, where the dull patronage of government is counted upon to outvie the keen activity of private enterprise. What government failed to effect, however, with all its patronage and all its agents, was at length brought about by the enterprise and perseverance of a single merchant, one of its adopted citizens; and this brings us to speak of the individual whose enterprise is the especial subject of the following pages; a man whose name and character are worthy of being enrolled in the history of commerce, as illustrating its noblest aims and soundest maxims. A few brief anecdotes of his early life, and of the circumstances which first determined him to the branch of commerce of which we are treating, cannot be but interesting.

John Jacob Astor[4], the individual in question, was born in the honest little German village of Waldorf, near Heidelberg, on the banks of the Rhine. He was brought up in the simplicity of rural life, but, while yet a mere stripling, left his home, and launched himself amid the busy scenes of London, having had, from his very boyhood, a singular presentiment that he would ultimately arrive at great fortune.

At the close of the American Revolution he was still in London, and scarce on the threshold of active life. An elder brother had been for some few years resident in the United States, and Mr. Astor determined to follow him, and to seek his fortunes in the rising country. Investing a small sum which he had amassed since leaving his native village, in merchandise suited to the American market, he embarked, in the month of November, 1783, in a ship bound to Baltimore, and arrived in Hampton Roads in the month of January. The winter was extremely severe, and the ship, with many others, was detained by the ice in and about Chesapeake Bay for nearly three months.

During this period, the passengers of the various ships used occasionally to go on shore, and mingle sociably together. In this way Mr. Astor became acquainted with a countryman of his, a furrier by trade. Having had a previous impression that this might be a lucrative trade in the New World, he made many inquiries of his new acquaintance on the subject, who cheerfully gave him all the information in his power as to the quality and value of different furs, and the mode of carrying on the traffic. He subsequently accompanied him to New York, and, by his advice, Mr. Astor was induced to invest the proceeds of his merchandise in furs. With these he sailed from New York to London in 1784, disposed of them advantageously, made himself further acquainted with the course of the trade, and returned the same year to New York, with a view to settle in the United States.

He now devoted himself to the branch of commerce with which he had thus casually been made acquainted. He began his career, of course, on the narrowest scale; but he brought to the task a persevering industry, rigid economy, and strict integrity. To these were added an aspiring spirit that always looked upwards; a genius bold, fertile, and expansive; a sagacity quick to grasp and convert every circumstance to its advantage, and a singular and never wavering confidence of signal success.

As yet, trade in peltries was not organized in the United States, and could not be said to form a regular line of business. Furs and skins were casually collected by the country traders in their dealings with the Indians or the white hunters, but the main supply was derived from Canada. As Mr. Astor’s means increased, he made annual visits to Montreal, where he purchased furs from the houses at that place engaged in the trade. These he shipped from Canada to London, no direct trade being allowed from that colony to any but the mother country.

In 1794 or ‘95, a treaty with Great Britain removed the restrictions imposed upon the trade with the colonies, and opened a direct commercial intercourse between Canada and the United States. Mr. Astor was in London at the time, and immediately made a contract with the agents of the Northwest Company for furs. He was now enabled to import them from Montreal into the United States for the home supply, and to be shipped thence to different parts of Europe, as well as to China, which has ever been the best market for the richest and finest kinds of peltry.

The treaty in question provided, likewise, that the military posts occupied by the British within the territorial limits of the United States, should be surrendered. Accordingly, Oswego, Niagara, Detroit, Michilimackinac, and other posts on the American side of the lakes, were given up. An opening was thus made for the American merchant to trade on the confines of Canada, and within the territories of the United States. After an interval of some years, about 1807, Mr. Astor embarked in this trade on his own account. His capital and resources had by this time greatly augmented, and he had risen from small beginnings to take his place among the first merchants and financiers of the country. His genius had ever been in advance of his circumstances[2q], prompting him to new and wide fields of enterprise beyond the scope of ordinary merchants. With all his enterprise and resources however, he soon found the power and influence of the Michilimackinac (or Mackinaw) Company too great for him, having engrossed most of the trade within the American borders.

A plan had to be devised to enable him to enter into successful competition. He was aware of the wish of the American government, already stated, that the fur trade within its boundaries should be in the hands of American citizens, and of the ineffectual measures it had taken to accomplish that object. He now offered, if aided and protected by government, to turn the whole of that trade into American channels. He was invited to unfold his plans to government, and they were warmly approved, though the executive could give no direct aid.