11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

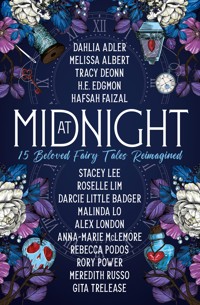

A dazzling collection of retold and original fairy tales from fifteen acclaimed and bestselling YA writers, including Tracy Deonn and Melissa Albert.A dazzling collection of fifteen original and retold fairy tales from acclaimed and bestselling writers.Fairy tales have been spun for thousands of years and remain among our most treasured stories. Weaving fresh takes and unexpected reimaginings, At Midnight brings together a diverse group of celebrated writers to breathe new life into our beloved traditions.Dahlia Adler, "Rumplestiltskin"Tracy Deonn, "The Nightingale"H.E. Edgmon, "Snow White"Hafsah Faizal, "Little Red Riding Hood"Stacey Lee, "The Little Matchstick Girl"Roselle Lim, "Hansel and Gretel"Darcie Little Badger, "Puss in Boots"Malinda Lo, "Frau Trude"Alex London, "Cinderella"Anna-Marie McLemore, "The Nutcracker"Rebecca Podos, "The Robber Bridegroom"Rory Power, "Sleeping Beauty"Meredith Russo, "The Little Mermaid"Gita Trelease, "Fitcher's Bird"and an all-new fairy tale by Melissa Albert

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

THE TALES RETOLD

Sugarplum – Anna-Marie McLemore

In the Forests of the Night – Gita Trelease

Say My Name – Dahlia Adler

Fire and Rhinestone – Stacey Lee

Mother’s Mirror – H. E. Edgmon

Sharp as Any Thorn – Rory Power

Coyote in High-Top Sneakers – Darcie Little Badger

The Sister Switch – Melissa Albert

Once Bitten, Twice Shy – Hafsah Faizal

A Flame So Bright – Malinda Lo

The Emperor and the Eversong – Tracy Deonn

HEA – Alex London

The Littlest Mermaid – Meredith Russo

Just a Little Bite – Roselle Lim

A Story About a Girl – Rebecca Podos

About the Authors

Acknowledgements

THE ORIGINAL TALES

The Nutcracker and Mouse-King – E. T. A. Hoffman

Fitcher’s Bird – The Brothers Grimm

Rumpelstiltskin – The Brothers Grimm

The Little Match Girl – Hans Christian Andersen

Little Snow-White – The Brothers Grimm

Little Brier-Rose – The Brothers Grimm

The Master Cat, or Puss in Boots – Charles Perrault

Little Red-Cap – The Brothers Grimm

Frau Trude – The Brothers Grimm

The Nightingale – Hans Christian Andersen

Cinderella, or the Little Glass Slipper – Charles Perrault

The Little Mermaid – Hans Christian Andersen

Hansel and Gretel – The Brothers Grimm

The Robber Bridegroom – The Brothers Grimm

About the Original Authors

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

A Universe of Wishes: A We Need Diverse Books Anthology

Cursed: An Anthology

Dark Cities: All-New Masterpieces of Urban Terror

Dark Detectives: An Anthology of Supernatural Mysteries

Dead Letters: An Anthology of the Undelivered, the Missing, the Returned…

Dead Man’s Hand: An Anthology of the Weird West

Escape Pod: The Science Fiction Anthology

Exit Wounds

Hex Life

Infinite Stars

Infinite Stars: Dark Frontiers

Invisible Blood

Daggers Drawn

New Fears: New Horror Stories by Masters of the Genre

New Fears 2: Brand New Horror Stories by Masters of the Macabre

Out of the Ruins: The Apocalyptic Anthology

Phantoms: Haunting Tales from the Masters of the Genre Rogues

Vampires Never Get Old: Tales with Fresh Bite

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands 2: More Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands: The New Apocalypse

Wonderland: An Anthology

When Things Get Dark

Isolation: The Horror Anthology

Twice Cursed: An Anthology

Multiverses: An Anthology of Alternate Realities

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

At Midnight: 15 Beloved Fairy Tales Reimagined

Print edition ISBN: 9781803363233

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803363240

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: February 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

‘Sugarplum’ © Anna-Marie McLemore 2023

‘In the Forests of the Night’ © Gita Trelease 2023

‘Say My Name © Dahlia Adler 2023

‘Fire and Rhinestone’ © Stacey Lee 2023

‘Mother’s Mirror’ © H. E. Edgmon 2023

‘Sharp as Any Thorn’ © Rory Power 2023

‘Coyote in High-Top Sneakers’ © Darcie Little Badger 2023

‘The Sister Switch’ © Melissa Albert 2023

‘Once Bitten, Twice Shy’ © Hafsah Faizal 2023

‘A Flame So Bright’ © Malinda Lo 2023

‘The Emperor and the Eversong’ © Tracy Deonn 2023

‘HEA’ © Alex London 2023

‘The Littlest Mermaid’ © Meredith Russo 2023

‘Just a Little Bite’ © Roselle Lim 2023

‘A Story About a Girl’ © Rebecca Podos 2023

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Caleb, the brightest star in the darkest sky

And in loving memory of Jo,who made dreams come true

INTRODUCTION

Fairy tales are often our earliest exposure to complex stories. So many of us were raised on narratives of princes and princesses, talking animals, powerful witches, and dreams coming true. But the more we read the stories, and the older we are as we read them, the more we come to understand all the different elements that formulate these foundational texts, including not just sparkling romance and rising from rags to riches but uglier themes like abusive parenting and manipulative trickery.

Are these stories meant to teach us morality? Are they meant to entertain? Are they cautionary, or are they aspirational? Is the intent for us to plumb their depths, or to sit back and simply embrace the magic? However you view fairy tales, there are certainly conversations to be had about their place in both literature and history, perhaps best exemplified by examining the way each story’s narrative changes over time and place. While the contributions in At Midnight were primarily inspired by the Brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen, and Charles Perrault, there are countless versions of these tales stemming from cultures all over the world, varied in every detail from character names to whether they end in laughter, tears, or bloodshed. And then, of course, there’s always the Disney effect.

In this anthology, some of YA’s most innovative authors take their turns breathing new life into the stories we know so well, remolding a hood into a hijab, a puss in boots into a coyote in high-tops, and a fatal fire into the flames of passion. The stories range from horror in the frigid reaches of Canada to historical fantasy in colonial India to a thoroughly modern tale of a social media Cinderella, with one thing in common: teens at the helm.

While the hearts of the originals have been preserved, prevalent themes of the original tales, such as transformation, toxic relationships, sibling rivalry, and the pursuit of the forbidden, are closely examined and spun on their heads to reflect their places (or lack thereof) in a more diverse world.

So polish that apple, double-check your roses for thorns, and settle in for a collection of absolutely inspired magic.

—Dahlia Adler

THE TALESRETOLD

SUGARPLUM

Anna-Marie McLemore

Inspired by “The Nutcracker”

RECIPE FOR THE SILBERHAUS ANNUAL CHRISTMAS PARTY

You will need:

• One intimidatingly enormous house (complete with actual columns)

• Your father’s boss and his wife

• Roughly thirty adults

• Approximately five hundred million bottles of imported wine and top-shelf hard liquor

• Enough fancy hors d’oeuvres to sandbag against five hundred million bottles of wine and liquor

• A Betty White impersonator

• Organic chicken tenders

• Dye-free soda

•A powder-puff tutu (No fucking way, not this year)

•A pair of split-sole ballet shoes you don’t mind anyone spilling grenadine on (See above)

•Substitute for above: the most annoying girl in five zip codes

Begin by arriving at the enormous house. Feel exceedingly small compared to the white pillars in front of the brick facade. It will be just as you remember it, so cloyingly and ridiculously nice that the cream drapes might wrinkle if you get too close. (But really, says Mrs. Silberhaus, make yourself at home.)

Observe the adults, all of them employees and their spouses who each want to make an impression at their boss’s Christmas party, one that suggests they are fun and relaxed and definitely not nervous about performance reviews in three months.

Say a prayer of gratitude as these adults deposit their children in the plush-carpeted finished basement. There, they will be fed the organic chicken tenders and dye-free soda by the nanny who used to take care of the Silberhauses’ now too-old-for-nannies children. She’s a Betty White type who is retired but comes out of retirement whenever the Silberhauses have a party. About five different parents will bring her plates from upstairs—Knock, knock, I thought you might want some grown-up food—as an excuse to make sure their children haven’t destroyed anything priceless.

It is good that the children are down here. No kid should see what’s going on upstairs.

Upstairs, witness the opening of the five hundred million bottles of imported wine and top-shelf liquor, or at least enough so that by the end of the night, most of the adults present have revealed themselves to be either hard drinkers or willing to just play one on TV for the night. Witness the artful arrangement of hors d’oeuvres on gilt-edged plates, directed by a chef who demands absolute silence for the sake of her artistry (and really, you have to admire the woman for being able to shut up the rich people who hire her).

Cringe at how few people are here. Your mother and father are always determined to be among the first to arrive, proving to your father’s very white boss and his very white wife that just because you’re Mexican doesn’t mean you can’t show up on time. While Mr. Silberhaus leads your father to the wine fridge so your father can praise his choice of vintages for tonight, your mother will help Mrs. Silberhaus arrange overpriced cookies on pewter serving trays. No, the catering team will not do this part, because lifting the cookies from their glossed white bakery boxes makes Mrs. Silberhaus feel as thrillingly domestic as if she’d baked them herself, and inviting a brown woman to do it with her makes her feel like a good person.

Meanwhile, take this opportunity to warm up your muscles, stretch out, work on that stubborn spot on your left calf that always feels tight. Because partway through the party—when she’s had her third or fourth glass of sémillon—Mrs. Silberhaus will ask if you could show her guests just a little of your ballet, it always makes me feel so festive, won’t you indulge us, just this once? And all the other drunk people will clap their hands like you are Tinker Bell and they can make you light up by applauding.

But Mrs. Silberhaus is your father’s boss’s wife. And when Mrs. Silberhaus gets what she wants, and when she gets to show off to her friends, she’s happy. And when you have done something to make Mrs. Silberhaus happy, Mr. Silberhaus is happy with your father.

So you indulge them. Just this once.

Repeat.

Just this once.

Every fucking year.

But not this time. This year, you will not dance. This year, omit the tutu and the ballet shoes, both of which you have left at home, and please note the following alterations to the previous directions:

This year, there is something else Mrs. Silberhaus wants from you. And that is to go cheer up her sullen daughter. Petey Silberhaus is always a little sullen, but in addition to being sullen she’s also currently a little sad. She screwed up her arm playing hockey or frozen crew or whatever it is she does at the school she goes to.

Having to interact with Petey more than usual is not ideal, but it is far better than dancing for a bunch of drunk people like a figurine on a music box, so you will gladly do it.

Smile as Mrs. Silberhaus leads you from the marble foyer up the stairs. Try not to stare at her hand on the banister, the nails impossibly shiny, like the inside of a shell. If you stare, you will feel compelled to hide your own nails, which are bitten down. Yesterday you applied sparkly fuchsia polish, which is already chipping.

Smile again as Mrs. Silberhaus says, “Petey’s going to be so glad to see you. She’s always liked you.”

Refrain from telling Mrs. Silberhaus that no, Petey has not always liked you. There was just a stretch of years where you and Petey were the only kids around the same age at these parties, cowering away from the older ones and staying out of the way of the younger ones, who were so sugar-infused they were bouncing off the holiday decor.

Do not roll your eyes when Mrs. Silberhaus’s delicate knock and song of “Your friend is here” is met with a grunt of acknowledgment from the other side of the door.

Gain an unexpected modicum of respect for Mrs. Silberhaus when she gives you a tight-lipped smile and a “Good luck,” because Mrs. Silberhaus apparently knows just how much of a delight her daughter is not, and you were not aware of this.

Open Petey Silberhaus’s bedroom door.

Observe Petey sprawled on her bed with a book (has she gotten taller since the Siberhauses’ Fourth of July party? Really? Again? While you’re still waiting for Madame Arnaut to decide you’ve reached a suitable height to audition for Aurora and Cinderella?).

Observe how your dress, which you loved until this moment, looks ridiculous in the same room with Petey’s T-shirt and sweatpants.

Observe how Petey sees you, eyes the full length of your dress—with its pink-mauve satin, its tea-length tulle, its trailing ribbons and lace detailing that you and your mother both decided were adorable—and bursts out laughing.

Say, “Shut up.”

“You look like a sugarplum.”

“And you look like an asshole. No special outfit required.” Sit on Petey’s bed with the full force of your Mexican ass, wrinkling the duvet as much as possible.

Ask Petey: “How did you get out of this?”

When Petey lifts the cast on her arm, say, “Yeah, I don’t believe it for a second. If your mother wanted you down there, you and your cast would be in your best blazer.”

“I’m a moody bitch these days,” Petey will say. “She doesn’t want me ruining her party. This is just a good excuse. She gets to tell me to rest and feels like a caring mother. I get out of smiling at everyone’s vodka breath. We all win.”

Look at the cast and ask, “Hockey?”

“Curling.”

“You are not on a curling team.”

“Oh yes I am.”

This will annoy you, because you watch curling whenever it’s on TV, and you think it’s kind of hot, and you refuse to let Petey Silberhaus be hot or even hot-adjacent.

Try not to glare when Petey smirks and says, “Oh, you’re into that?”

“You wish.”

“You want to see my rocks?”

“Eww.”

“The ones we slide over the ice. You’re the one making this dirty.”

Spread your sugarplum skirt so it covers as much of Petey’s duvet as possible. Gold and silver embroidery and the pink underskirt everywhere. Take up the whole fucking bed.

Ask Petey: “What are you reading?”

“‘The Nutcracker.’”

“Wow. I didn’t think you were the holiday-spirit type.”

“Holiday spirit, my ass. This is the original. This shit is weird.”

“How?”

“Look.”

Do not hesitate when Petey scoots a little closer on the bed and holds the book between you. If you hesitate, Petey will know that the fine hairs on her arm brushing against yours just made you freeze for a second. Do not think too hard about this. Remember that Petey is the Most Annoying Girl in the World. Petey has made fun of every frilly holiday dress you’ve ever worn.

When Petey asks, “What?” just shake your head like you’re shrugging something off.

When Petey asks, “Are you okay?” just nod.

Skim the words in Petey’s book. The part about Maria bandaging the broken nutcracker with a ribbon from her dress. The grandfather clock. The dolls coming to life. Maria rescuing the nutcracker prince from being taken prisoner by throwing her slipper at the mouse king (really? That works? Should you try this at school?).

Agree with Petey that this shit is indeed weird.

Alert when your mother calls your name from downstairs.

Sigh.

Get off Petey Silberhaus’s bed.

Stop just before the door when Petey says, “Good luck. I’ll be here if you want to know what happens next.”

Make a round at the party. Let your mother show you off while your father pretends to care about the conversation he’s having alongside the giant Christmas tree with its giant glass ornaments.

When Mrs. Silberhaus asks if you’re “going to do your little dance for us this year,” like you’re a toddler in a sequin-edged tutu, say nicely, “Not this year.”

When Mrs. Silberhaus lets out an exaggerated awwww of disappointment and says, “What a shame. Our guests always look forward to it,” smile and say, “Maybe next year.”

Hope that the sugary smell of white wine on her breath means she will not remember you saying this.

You will not put on your split-sole ballet shoes and dance on the fluffy carpet in their living room. You will not be their Christmas doll. You will not be their Marzipan, or their Sugar Plum Fairy, or their Spanish Dancer.

Wait until both your parents are absorbed in conversation and go back upstairs. You are being nice, after all. You are keeping Petey company. You may be denying Mrs. Silberhaus the show she wants, but you are lifting the Christmas spirits of her youngest child.

Ask Petey and her open book, “What’s happening now?”

“There’s a court astrologer. And a ridiculously convoluted prophecy. The usual.”

When Petey eyes your dress again, sit on Petey’s bed and throw your skirt even wider, so Petey can’t even move without brushing it.

When Petey flicks away a corner of tulle and asks, “Is that for this year’s performance?” tell her, “No, I’m not doing that this year. I told my mother.”

“So she punished you with that dress?”

Throw the fluff of your skirt at Petey Silberhaus. “I picked this out, you jerk.”

Try to see it coming.

You won’t. Try anyway.

Try to see it coming that when you and Petey Silberhaus bat the layers of your skirt back and forth like you’re having a pillow fight, a film of heat brushes against your legs like another layer of tulle. When ribbons trailing off your skirt stroke Petey’s arms, do not notice that she’s blushing.

Tense your legs until that invisible layer of tulle vanishes.

When it doesn’t vanish, when Petey goes still, with her mouth slightly parted and her eyes half-closed, like she’s looking at you for the first time, do not come closer.

Do not kiss Petey Silberhaus. Your father’s boss’s daughter.

Seriously. Do not kiss Petey Silberhaus, no matter how much you like how she smells right now or how her hair is getting in your face. Kissing Petey Silberhaus will fuck up your perfect chignon and probably your heart.

Both love and hate your mother for calling your name from downstairs again at exactly this moment.

When you and Petey look at each other, startled out of what was just about to happen, break the tension by saying, “If they’re relying on me to be the life of the party, this is gonna be a disappointing party.”

Do not notice how cute Petey’s half smile is.

Do not look back as you leave the room.

Try not to jump fifteen feet when, downstairs, Mrs. Silberhaus comes up behind you, puts her hands on your upper arms, and chirps, “I just heard the good news.”

Wonder for a second who’s pregnant, until Mrs. Silberhaus says, “Your mother says I might be able to persuade you to dance for us after all.”

Notice how your next breath feels like it takes two minutes.

Notice how the whole party goes still, reduced to this woman’s hands on your arms.

Look for your mother.

Say, stammer, “I didn’t bring my stuff.”

Locate your mother. Who is holding out your ballet shoes with a pained, apologetic look.

Imagine what polite, delicate pressure Mrs. Silberhaus put on your mother while they refreshed the trays of holiday cookies.

We’ve just all gotten to expect it. It’s sort of a holiday tradition, isn’t it? We’ve always considered your daughter part of our family. We just love seeing her.

Look back at Mrs. Silberhaus and say, “I didn’t bring a costume.”

Look forward again, at your mother, as Mrs. Silberhaus says, “Oh, you can dance in that dress, it’ll be perfect. You look darling.”

Know that, in this moment, you hate your mother for the betrayal held in those satin shoes, but that you hate her more for letting you think you might get to say no to this.

Watch your hands take the slippers.

Try not to flinch as Mrs. Silberhaus’s golden, perfectly barrel-curled hair brushes your shoulder and as you realize that everyone at this party is watching and waiting.

Do not look at your father, who looks at a glass ornament, as though he is ashamed that his daughter must please not just his boss but his boss’s wife.

Slip on the ballet shoes.

As Mrs. Silberhaus gives sheet music to the man she hired to play the piano for the evening, do a half-assed job of warming up your muscles and stretching. Everyone is watching, and stretching does not interest them.

Then dance.

Dance for everyone in the Silberhauses’ enormous, richly upholstered living room.

Dance as the Christmas tree seems to grow toward the vaulted ceiling, the ornaments swelling to the size of gazing globes.

Dance with bourreés as delicate as the Marzipans.

Give them the confident port de bras of the Spanish Dancer.

Arabesque as gracefully as the Sugar Plum Fairy, with the tulle of your party dress spilling across your legs.

Leap high with each pas de chat. Spin in a coupé jeté, secretly hoping you will break something expensive. Spin in piqué turns so fast the party guests must move back toward the walls.

With one of your turns, lose your spotting just enough to notice Petey at the railing at the top of the stairs. Try not to see the pain in her face, like she wants to tell you that you can get off the music box, that you don’t have to stay there. Do not fault her for realizing that you don’t get to stop spinning until the music box winds down.

Dance, and ignore the tiny tears in your muscles from not being properly warm. Dance, and feel the hard edges of the split soles digging into the bottoms of your feet each time you point your toes. Dance, and let them all watch, like a brown music box ballerina is the strangest marvel they have ever seen.

When the music stops, hold your arms in the perfect pose.

Wait the half second before they applaud and roar their approval.

Curtsy with the shy humility of a snow princess. Stand back up with a fake smile so big it will leave your jaw tight until tomorrow morning.

Stand there, in the middle of the living room, as Mrs. Silberhaus laughs and applauds her thanks. Stand on the plush carpet as wine-breathed adults in sparkling party clothes tell you what a graceful young lady you are.

Stand there, as your mother and father are swept into new conversations that begin with what a lovely and talented daughter they have and then quickly move to how even more lovely and talented their own children are.

Keep smiling, so big that everyone could still see it if you were onstage.

Keep smiling, especially when you realize that the Betty White impersonator brought her charges upstairs for the performance. Smile at the ones who pull on the tulle of your skirt and ask if you’re a princess. Will the tears on your cheeks to turn into dewdrops or sugarplums or snowflakes or marzipan so that they will not see them.

When Betty White tells these children that it’s time to let the princess get her beauty sleep, when she claps her hands and says she has cupcakes for all of them, give her as much of a silent thank-you as your frozen-in-place expression will let you.

Keep your arms in demi-seconde, as though you are still onstage, even though no one is watching you now.

When a hand appears in front of you—open, a little tilted down—you wonder if you are imagining the Sugar Plum’s Cavalier in this sparkling living room. Brush your fingers over the hand to see if it’s really there. When you do this, Petey will clasp your hand and lead you upstairs.

Feel each stair in the thin satin of your slippers.

Sit on Petey’s bed and stare out the window, your own tears blurring each star into a silver ornament.

When Petey asks, “Are you okay?” try to unknot your throat. Fail.

Barely hear Petey as she says, “Wait here.”

Laugh, dabbing away a mascara-dyed tear, when she comes back with a cake and two forks. She will not bring plates, except the decorative frilled-edged one underneath the cake. “My mom ordered a bunch of them. They’ll never notice one’s gone.”

When Petey sits on the edge of the bed next to you, join her in tearing the cake apart with the forks. Tear open the shell of swirled meringue frosting to reveal the Christmas-red cake underneath. Let the sugar and meringue dissolve on your tongue.

When Petey asks, “Are you sure you’re okay?” lie back on her bed, your skirt fluffing out.

Hand Petey the book and say, “Just tell me what happens next.”

Shut your eyes as Petey Silberhaus tells you what happens next.

Feel a glittering cold on your face. Wonder if the tears on your cheeks are in fact turning to sugarplums or marzipan. Then open your eyes and realize that as Petey reads, snow is falling from the ceiling of her room. With each word she reads, a few more snowflakes drift down over the bed, gilding the satin and tulle of your skirt, glittering in Petey’s hair. Watch the walls around you vanish, revealing a pine forest.

Take your cavalier’s hand and lead her into the snow-silvered trees. Pull a ribbon off your dress and gently tie it around her cast. Throw one slipper, then the next, at anyone who tries to follow you.

Kiss the snowflakes catching on Petey’s eyelashes. Lick the tiny meringue snowdrift off her lower lip.

Know that you will have to dance for them all again next year, and the year after that, and every year that your father works for Mr. Silberhaus and that his wife is amused by your dancing.

Know that you will have to leap onto the thin velvet stage of their music box whenever they turn the windup key.

But for now, dance under the silver winter of this night, for no one but your cavalier, and you.

IN THE FORESTSOF THE NIGHT

Gita Trelease

Inspired by “Fitcher’s Bird”

That spring, the girls began to disappear.

The first girl, picking tea in the white heat of midday.

In those long rows of emerald-green bushes, vipers sometimes sunned themselves, threaded through the branches like deadly streamers. But if it’d been a snake that killed her, where was her body?

The second girl, herding goats through the cool of a pine forest. On the other side bloomed a wildflower meadow perfect for picnics where, by a stream, blue butterflies danced. Two days later (most of) the goats found their way back. The girl did not.

The third girl—the skin on the back of my neck prickled when my sister Maya told me—sitting in the shade of her own doorway, mending a rip in her sari. Her brothers heard her scream. In the space of a breath the enormous cat vanished in the elephant grass. Throwing rocks, they gave chase, but the tiger was inhumanly fast. They shouted her name until their throats ached, but all that came back were echoes.

The third girl was the daughter of my grandmama’s driver.

Incandescent with rage, Granny swept off the veranda of Orchid House, into her car, and down the hill into town. There she stormed the British club, where no Indians, not even Granny, were allowed. In her deadliest voice she demanded the chief of police send for Captain Colin Fitcher. An army veteran, he’d once killed a man-eating tiger that had taken 210 lives. And though normally the deaths of three Indian girls wouldn’t have raised a single English eyebrow, Granny was the widow of a Rajput prince, and that was the kind of thing the British understood.

Captain Fitcher was summoned. As it turned out, he’d been nearby the whole time. He’d arrived last year from the west; no one knew where. No one had seen him; none of us knew what he looked like. He didn’t socialize with the British, and he definitely didn’t socialize with us, but lived alone on the outskirts of town, in an old bungalow overrun by jungle. Without knowing it was his, I’d seen his place on my way to school. Five red points of roof above the treetops, a chimney snarled in vines.

Our lives changed after that. While Fitcher with his men and guns stalked the tiger (many against one), we girls were trapped indoors. Except for school, but there the nuns were more eagle-eyed and suspicious than ever. Finger in the air, Sister Thomas warned, “Your very lives depend on being obedient!” Which only made me want to race out of assembly and smoke bidis behind the refectory with Ash and stay out all night, doing wild, unpredictable things.

Our parents and everyone else who should have come up from Delhi (like living in an oven) didn’t, because of the tiger. A telegram, though, arrived for me: Ash’s ship had docked in Bombay. After almost a year away at Oxford, there was only one long train ride left between us. In the muggy afternoons, I listened for the steam engine’s distant whistle and wondered: After all this time, had Ash changed? Had I?

I used to be a fairly good student (Lili’s work is exemplary, if at times too imaginative), but since the killings it’d become impossible to concentrate.

The air in our biology classroom was always thick and warm, like something you could touch. Next to me, Savita doodled hearts in her notebook; dust motes drifted in the syrupy sunlight. As Sister Agnes endlessly explained cell division, I stared out the window—and saw the curtains twitch. When they trembled again, longer this time, I knew: something was trapped behind them.

Carefully I lifted the fabric. Caught between it and the window was a silvery moth. Its wire-thin legs tapped at the glass that must have looked like sky but was only a dead end. Exhausted, it beat its scalloped wings, slow as death, and then went still.

I stood and shoved up the window’s heavy sash. It made a terrible cracking sound.

Sister Agnes spun around. “You, Lili! Where do you think you’re going?”

I dropped into my chair. “Nowhere, Sister! I was just—”

The moth crawled onto the windowsill. The other girls tittered.

“Just what?”

She was the biology teacher. If anyone would understand, she would. “A moth was trapped behind the curtain—”

Sister Agnes frowned, wrinkles knotting above her glasses. “What a story! Don’t think for a minute I’ve forgotten your escapade at the lake. Didn’t you go out the window then as well? And lead so many others into your misbehavior? You are a rash and irresponsible girl, Lili Blake.”

It had been my idea to go down to the lake.

Last spring, Ash and I had planned to sneak out of school and rent a boat. To row out onto the jade-colored water with the hills rising lush around us, and beyond them the silvery peaks of the Himalayas. To lounge on tasseled cushions and stare up at the clouds—or at each other. To feel the sweet air on our skin, the dazzle of him next to me: one boat ride, just us, before he left for England. Was it too much to ask?

Apparently it was, because Edith Vane saw me climbing over the school wall and followed (no imagination), as did three of her friends. They rented one boat, Ash and I another. But so many English girls on the lake set an alarm ringing in the boat wallah’s mind, and he sent a boy up to the school. We’d barely left the dock when the headmistress stepped out of a rickshaw, her face murderous.

Ash had tried to take the blame—one-eighth Indian being more credible to the headmistress than one-half—but it didn’t work. Instead my parents came up from Delhi to consult with the headmistress (everyone was very concerned). At the train station, before they left again, my English father said fondly, “Do try and be careful, darling, won’t you? We can’t always be here to get you out of scrapes.” And my Indian mother said, “You mustn’t draw attention to yourself, Lili. We only want to protect you.”

From what? But I think I knew, even then.

Normally Sister Agnes would have kept me after school, writing on the chalkboard I will not open the window or I will not save a moth. But these weren’t normal days. That morning a farmer had spotted a tiger on the winding road to school. When the nuns learned of it we were sent home with our books and extra assignments.

It got hotter.

Late in the afternoons, thunder murmured promises of rain. The monsoon was coming. While Maya scribbled secret letters she paid the sweeper to deliver, I sat on the veranda, kicking my heels against the wicker rocker, tormented by whatever adventures Ash was having without me.

The walls of Orchard House crept nearer and nearer until I felt like Alice in the storybook we had, grown so big in Wonderland she no longer fit indoors. In the black-and-white illustration she looked angry enough to kick the whole house down. Everything felt too close, even the jagged teeth of the far-off mountains.

At night a tiger roamed the hills behind the house, growling and huffing. In the pitch black I slipped into Maya’s room and lay next to her as the ceiling fan clicked round and round.

Against the window, the oleander tapped nervous branches.

Had the girls who’d been killed heard a warning—a monkey’s call, a snapped twig? Or hadn’t they known the End was coming closer, making no more sound than a shadow? Did they turn and fight, or run?

Once, I heard the tiger breathing, hot and restless and close. As if it were on the other side of the wall, whispering in my ear. I made a dark wish then, the kind you’re not supposed to make: I wished the tiger would slip through Fitcher’s snares, past the beaters and shooters that roamed the hills. Free, and away from here.

My wish didn’t come true—not all of it.

Because three days later, Captain Fitcher announced that he’d killed two man-eating (girl-eating) tigers.

Granny threw a party to celebrate.

* * *

It was nearing dusk when the first guests arrived. Drinks fizzed on silver platters; jazz poured out of the gramophone’s trumpet-shaped horn. On the terraces, people were laughing and gossiping as if they’d been released from a long siege. Which I suppose they had been. As I lingered on the veranda, hoping Ash would show up soon, the scarlet flowers of the bougainvillea dissolved like ink, and far below, the eye-shaped lake turned from green to silver.

Maya came up behind me, her bracelets clinking as she laid her hand lightly on my shoulder. I smiled, already less lonely. She was two years older than I was and fairer, with hazel eyes and red in her hair, so pretty in her peacock-blue gown with its sparkling glass beads. I’d put on a smoke-gray silk dress that brought out my brown skin and amber eyes—though compared to Maya’s, it felt suddenly too plain.

“I adore that dress,” she said, “though I wonder if you might be too glamorous to be my little sister.” I could always count on Maya to know how I was feeling. “Is Ash here yet?”

My throat constricted, and I shook my head.

“Never mind. If he doesn’t come tonight, it’s only because he’s not back in town. The trains from Bombay are dreadfully slow.” Trying to distract me, she said, “Have you seen Captain Fitcher?”

The party was crowded now, the line of black automobiles on the street below getting longer. On the upper terrace, surrounded by a crush of people, stood a tall Englishman in a crisp linen suit and a straw fedora. He was lean, with light eyes and hair, but deeply tanned (crouching in the sun, waiting to kill animals). A hunting knife hung conspicuously from his belt. Maya’s best friend was saying something to him and pointing to the hills.

“That’s got to be him there,” I said, “with Gayatri.”

She was the most beautiful girl in town, with huge almond-shaped eyes and a quick, daring smile she’d give you before she did something outrageous. Not the kind of girl to be starstruck. But there she was, Fitcher’s white hand on her arm, her face turned up to his.

“She’s positively spellbound,” Maya said with a laugh.

Seeing Gayatri like that sent a ripple of unease through me. Conspiratorially I said, “Let’s see if she needs to be rescued.” Together we went down to the lower terrace and squeezed into the group.

“The tiger’s pugmarks,” Fitcher was saying, “what you’d call paw prints, were almost as big as this.” He stretched his hand out as wide as it would go. In the setting sun the skin between his fingers glowed red.

“And to kill such a large animal . . . ?” Gayatri asked.

He smiled, showing his teeth. “I become the top predator.”

“How?” she asked. “Do you wait overnight in a machan? Put out bait?”

Bait? I wanted to kick her. She knew hunters tied a baby buffalo to a stake and waited in a blind for the tiger to come. What was happening to her?

“It’s not quite so simple.” Fitcher’s hand came now to rest on my sister’s shoulder. “Shall I explain?”

Maya nodded, and he told the story of how he’d tracked the man-eater of Chowgarh. For months it had deliberately led him astray. But he’d persisted, following clues of bent grass and fur tufts on branches until he put an end (shot through the heart) to the tiger’s reign of terror.

“But, Captain?” my sister asked dreamily, so unlike herself. “What makes you the best at it?” Her hazel eyes had gone soft, unfocused, and they didn’t leave Fitcher’s face. She reminded me of a snake charmer’s cobra, so mesmerized by the sway of the street performer’s instrument, it forgets it has fangs.

I nudged her in the ribs. “Come with me to see Granny. Please.” But she didn’t even turn to look at me.

“Patience,” Fitcher replied, “and observation. Control. When you come down to it, the tiger’s broken. It’s sick or hurt and can’t catch its normal prey. So it hunts something easier.”

“Like girls,” I said.

Fitcher’s ice-chip gaze swiveled to me. “Something defenseless. Once a tiger sees how easy it is, it’ll keep coming back, more dangerous than ever.”

The horror of it made the hair on my arms stand up. Unfazed, Gayatri batted her lashes at him. “What’s the biggest tiger you’ve ever shot?”

He straightened the lapels of his jacket. “Fifteen feet, nose to tail.”

“That’s hard to believe,” I said under my breath.

But Fitcher heard me. “Why’s that?”

“Haven’t you British hunted our biggest game animals to death?”

“Between us and your princes we’ve done quite a job of it, that’s for sure.” He hid his hands in his pockets. “I’m going to stuff them—real as life. By the time I’m done they’ll look like they could walk out of the room. The safest way to see wild animals, don’t you think?”

Bile rose in my throat as I imagined him stripping a tiger’s skin from its flesh. Peeling it back and filling it with something else. Making a trophy of it. Making it safe.

“We’ll go, won’t we?” Gayatri put her arm around my waist and Maya’s. “And see these tigers for ourselves.”

Around me rose a chorus of yes, please, me toos. I scowled at Maya, trying to get her attention, but like the rest of them, she only had eyes for Fitcher. But I hadn’t forgotten the desperate tiger padding around Orchid House, whispering through the wall. I slipped away and left them to their unsettling fascination.

Over us the sky was deepening to indigo, while down in town, lights snapped on in the houses. At the lush edge of our garden stood Granny under her oldest mango tree. Admiring the fruit-laden branches while adjusting his striped college tie was Ash.

I paused in the shadows, drinking him in. He was handsome as always, his tawny hair tousled, the easy smile he’d had since we were kids softening the now-sharp line of his jaw. Away from our Indian sun, his skin had gone pale. He looked tired and worn, as if he’d passed through too many hands. I wanted to believe that he was who he’d always been: the boy who kept my secrets and said yes to every adventure. My oldest friend. My love.

“Ash!” I kicked my fancy shoes off under a rosebush and raced barefoot across the cool stones. “You’re home!”

“Lili, darling!” His face changed when he saw me, like he’d never been away. And though my grandmother gave us both a stern look, we cheerfully waved so long and disappeared into one of the garden’s secret haunts. For a delicious half hour there were no more hunters or prey, only the two of us under a jasmine-woven pergola, our feet in the fountain as we watched the stars spark, one by one.

There was so much to catch up on. The weeks of travel by train and by ship, glamorous London, scholarly Oxford. Punting a boat on the River Cherwell in the fall, the winter so damp he never felt warm and was teased for wearing two sweaters indoors. The libraries full of books and the demanding classes, the afternoon cricket matches and the dinners that ended at dawn.

I could tell he loved it, and it hurt, more than a little. “Was it at all strange, being there?”

He fell silent, considering. “No one seemed to care where I came from, if that’s what you mean.”

On the seat between us, our fingers lay braided together, mine dusky, his almost white. Could being half English and half Indian matter less in Oxford than it did here? Or was it that I was half, and he an eighth? “I’ve been thinking . . . I could try to get into St. Hilda’s.”

“You’d come with me to Oxford?” he said, bewildered. “But I thought you loved it here.”

The music on the gramophone had gone swoony, sad. “It’s not the same anymore.”

“What do you mean?”

I sighed. “It’s as if there’s always been a rope around my ankle, but I’ve only just noticed it.” I told him about the endless weeks of not being able to do anything, the cautions and be carefuls, my life slipping away like water. The nuns and Granny and everyone else forcing me to wait—to be safe—until I thought I might explode. And then, how even after Fitcher had killed the tigers, they wouldn’t let me do what I’d done before.

“Darling, listen to me.” His eyes were fierce and serious. “If you want to go, I swear I’ll do everything I can to help convince your granny. And your parents. I promise, Lili—I won’t leave you behind.”

“Truly?” Tears I’d held back since the girls had first disappeared pricked at my eyes. I squeezed his hand, hard.

“Truly.” Tucking a strand of hair behind my ear, he let his fingers trail down my cheek. “You’ll dazzle them—Oxford’s never met anyone like you.”

When we finally emerged from the garden, star-dazed, drunk on each other, most of the guests had left, including Fitcher. Ash and I said goodbye on the lower terrace, where in the dark the steps zigzagged down to the road.

Suddenly formal, he said, “May I walk you to school tomorrow?”

Maya, Ash, and I had walked to school together for years; the whitewashed walls of the boys’ school faced ours across the street. But this felt deliciously different. “The other girls will burst into envious flames,” I teased.

“And you’ll warm your lovely hands on the fire.” He brought my face close and kissed me, slow and delirious. “Until tomorrow, then.”

Heat burned through me as I watched him go. I had to find Maya and tell her.

In her bedroom the coverlet was turned down, the fan clicking away, but she wasn’t there. Uneasy, I went to see our old nurse, who told me Maya and Gayatri had left the party with Captain Fitcher, to see the tigers he’d killed. “My poor girl!” she cried. “No sense, going to a man’s house. Even worse, an Englishman’s!”

“You’ve always insisted she was the sensible one,” I said, more cheerfully than I felt. “You’ll laugh when she tells us about it in the morning.”

But in the morning, Maya hadn’t come home.

* * *

Before it was properly light, I crept down the hall and found her room empty, the perfectly made bed still waiting for her, eerie and wrong. In the kitchen I wolfed down several cups of tea, an excuse to linger and listen as, just outside the door, the mustached police chief briefed Granny. He told her his men had already combed the gardens and rooms of Orchid House for a sign of the girls and interviewed Fitcher. It was true that the girls had wanted to see the tigers, he’d said, but once in town they’d changed their minds. He’d dropped them near Gayatri’s house.

But I knew they wouldn’t have gone there unless they’d been in trouble; Gayatri’s father was a closet drinker, uncomfortable to be around. Either Fitcher had scared them so much they’d gotten out of his car in town, or they’d continued with him to his house.

Despite the heat of the kitchen, I shivered. Everything about this felt wrong.

When the police chief finally left, I turned on Granny. “Did the police search Fitcher’s house?”

“Why would they?” She dried her damp cheeks with the end of her sari. “It was a tiger that did this! My granddaughter is lying maimed in some forest, suffering—”

A tiger, snatching up two girls in the center of town? If I had told Granny this, she’d have scolded me for imagining things. But Fitcher had hypnotized them all into believing something they’d otherwise never accept as true.

Before Granny could tell me I had to stay home from school because of the tiger, I hurried down the sixty-three steps to the street. At the bottom was an iron gate with a brass bell. Ash was due in an hour, but I couldn’t wait. Instead I wrote him a note saying I’d gone to look for Maya, which I wrapped around the bell’s clapper. It was a system we’d come up with when we were kids; he’d know there was a message as soon as he opened the gate and the bell didn’t ring.

I headed down the road, my school shoes setting off plumes of dust. The day was overcast, the air so wet it felt almost like rain. I went first to Gayatri’s and talked to her family’s sweeper, who knew everything that happened at the house. He confirmed the girls hadn’t come home. I told myself it was too soon to panic, but it happened anyway, the fear ticking like a too-fast watch inside of me. Almost running, I went the places the police wouldn’t know to check. Like Gayatri’s favorite sweetshop, and the stand of the flirtatious chai wallah where Maya bought tea after school. I even rushed down to the wide green lake, in case they’d rented a boat and capsized—but no one had seen them.

It was as if they’d simply disappeared.

But if I’d learned anything from what happened that spring, it was that girls didn’t just disappear. There was always a reason.

It was already afternoon by the time I found the road to Fitcher’s house. The entrance was so overgrown and shabby that I’d passed it twice before spotting the half-hidden sign that said Fitcher. A faint dirt track wound through the forest, climbing slowly into the gloom. Though I kept to the center of the path, dead branches clawed at my arms, overgrown grass hissing around my legs. The forest smelled wild, sharp and green. High in the canopy, monkeys shrieked back and forth. Among the dark leaves, birds’ wings flared yellow and red.

Suddenly, behind me, I heard a car’s engine, running fast. I scrambled out of the way just as a big black car roared up, with Fitcher behind the wheel.

He cranked down the window and stared. His eyes, I noticed, were bloodshot. “Has your sister been found? And the other girl?”

“I’m sure they’ll turn up eventually. No one’s at all worried,” I lied.

His hands gripped the wheel so hard the knuckles were white. “What are you doing here, may I ask?”

I gave him a helpless shrug. “You said I could see the tigers.”

He relaxed then. “As you wish.” He leaned over and flipped the lock. The car door yawned open. Scarlet leather seats, the reek of cigarettes. “The house is still a way up the road. You’d best drive with me.”

I got in and closed the door. On his forearm was a clumsy bandage I hadn’t noticed last night. Pinpricks of blood had seeped through the gauze. He made small talk about the weather; I stared out into the forest, not wanting to give anything away.

We jolted along the track for several minutes before the trees backed off and the house came into view. It’d once been a grand bungalow with balconies and dozens of large windows. But the shutters with their peeling red trim were closed, as if the house were asleep. Mold ferned the once-white walls; rot had eaten away at the veranda’s pillars. From the gutters trailed eager, grasping vines. What had once been a pretty garden had escaped its fence, already halfway to jungle.

He noticed me looking as we got out. “I’m not here very much, you see.”

Behind us, the car ticked as it cooled. The lake glinted through the trees. “You have a nice view.”

The corners of his mouth turned down. “Nothing like your grandmother’s. Come in and see my collection.”

Up the stairs, across the sagging veranda, and in through the front door to a central hall. With the shutters closed, it was suffocatingly hot, and dark. It smelled of awful things: decay, the gag of formaldehyde. Nothing moved; the house was secretive and still.

Then Fitcher flicked a switch and lights blazed on overhead.

I flinched—the room was filled with eyes. Horns and teeth and tusks.

The severed head of a sambar, antlers curved like a crown. A spotted chital deer, its eyes dilated with fear. By the door loomed a pale-nosed bear, one paw forced out into a mockery of a handshake. An elephant foot, its toenails intact, had been transformed into a wastebasket; on a low table a tortoise’s shell held letters. Two prancing blackbucks with spiraling horns stood shoved against the wall, as if Fitcher had killed so many creatures he’d run out of room to show them off. Under an archway of ivory tusks hung an enormous tiger’s head, its mouth forever open in a silent scream. As I stared, a beetle crawled out of its ear and into a hole in the wall. And across the wide stone floor, as if they’d been slain where they stood, lay the pressed-flat hides of chinkara and lions and black-stippled cheetahs.

The safest way to see wild animals, he’d boasted. I bit down on the inside of my cheek to keep from throwing up.

Fitcher gestured at his trophies as if he were unveiling a work of art. “Impressive, aren’t they?” His voice climbed, almost giddy. “Don’t they look alive? Silent and—as a girl you must appreciate this—perfectly tame?”

The blackbucks’ almost-human eyes seemed to swivel to mine. Careful to keep the dread out of my voice, I pointed to the severed head and asked, “That tiger over there isn’t one of the man-eaters, is it?”

“Clever girl. Even I couldn’t have stuffed it that fast. Come, there’s more—shall I get you a nimbu pani as I show you around?” Fitcher flashed me a conspiratorial grin. “I suppose you’re too young for a cocktail.”

Had he offered Maya and Gayatri a drink? On the cheetah skins perched a few leather club chairs, a coffee table, a brass cocktail cart. It was cluttered with liquor bottles, but there was no sign it had been used last night. No lipsticked glasses. No crumpled napkins.

It didn’t mean much. They could have been here last night and Fitcher had cleaned away any trace of them. I needed to keep looking. “No, thanks, I’d just like to see the tigers—the ones my sister and her friend saw.”

Blandly, Fitcher said, “They never saw the tigers—they changed their minds.”

It sounded so reasonable. Girls were always changing their minds. Distracted, teasing, impulsive. But Maya and Gayatri weren’t like that . . . except at the party last night when they’d been enthralled by Captain Fitcher. His pale hands on their arms, their eyes locked to his. Hypnotized.

The police might have believed him, but I didn’t. Brightly, I said, “I would like to see the rest of your collection.”

He really looked at me then—watchful and patient—and seemed to come to a decision. “This way.”

He led me down a hall, flipping on lights, and I followed, searching for a sign that my sister and Gayatri had been there. On the walls hung animal hides and grim photographs of men posing with guns, dead animals under their boots. Rooms opened off on both sides, packed like cells in a hive. The farther we went from the front door, the darker they became. More full of shadows.

A phone shrilled next to me, and I nearly jumped out of my skin.

Fitcher snatched up the receiver. He listened, head cocked, then hung up. A blue vein stood out on his forehead. “Someone’s seen a tiger by the boys’ school—I must go. The rains could start any minute and wash away the pugmarks.”

Not yet. There was still so much house to cover. “But your collection—”

A slow, calculating smile. “Why, after coming all the way up here you must stay as long as you like.”

“Really?” If he was so at ease, maybe there wasn’t anything to see after all. Or maybe, the dead animals in the photos whispered, it is a trap.

“My house is your house. There’s loads to look at, so feel free to wander into any room you like. Take your time.”

I remembered the rooms we’d passed, some doors unlocked, others closed tight. “They’re all open?”

“The ones you’re allowed to enter are.” His eyes slid to the telephone, black and quiet on the table. “But before you go any farther, you must take off those dusty shoes.” He pointed to a pair of furred slippers tucked under the table. “Put those on instead, and don’t get them dirty.”

“I’ll be careful.” I unbuckled the straps of my Mary Janes and stepped into the slippers, rounded like paws.

“See you soon,” he said. “Be good.”

I waited until I heard him drive away.

The telephone table had a single drawer in it, a few inches high. Fitcher had glanced at the table, and now, in the silent house, it seemed to beckon me too. I had a prickling feeling, a kind of presentiment, that if I took hold of the brass knob and pulled it open and looked inside, there would be no going back.

Slowly I slid it toward me. The drawer was empty except for an iron ring bristling with keys of many sizes and shapes. They made a sound like splintering glass when I lifted them out.

Ahead of me doorways disappeared in the gloom.

I’d taken only a few steps when I felt something hard, like a pebble, in the toe of the left slipper. I turned the shoe upside down; a tiny ball fell out and rolled glinting across the floor.

My hand shook as I picked it up: it was a blue glass bead from Maya’s dress.

I ran down the hall, the keys in my fist. The first door I unlocked led to a study, wallpapered with moldering books. No sign of them. Then a dining room, glasses on a sideboard, a table feathered with dust. Nothing. Desperate, I kept opening doors: a sitting room with a horn chandelier, a moth-eaten billiard table, cold tiled bathrooms, and a large bedroom, mosquito netting a ghost over the bed. But no matter how many rooms I went into, no matter how many keys I tried, I could find no other trace of my sister and Gayatri.

At the end of the hallway waited one last door, plain and narrow.

As I hurried toward it, something rumbled in the distance. Thunder? I listened hard for the sound of Fitcher’s car. One heartbeat, two, three—nothing but rain in the hills.

I twisted the knob on the narrow door, but it didn’t open. Locked. There were a dozen keys I hadn’t used yet; I chose one and tried to fit it to the lock. Too big. I tried another one, smaller, and that too wasn’t even close. One after another I tried the keys, and none were right.

I was running out of time.

Frustrated, I stooped to look at the keyhole. It was tiny, curved like a fingernail clipping, so small it could only be unlocked by the tiniest of keys. I fumbled with the ring until I found it: tarnished silver, no longer than the first joint of my little finger. As I held it, the key burned cold against my palm. Now or never.

As soon as I fit the silver key into place, the door creaked open. The smell I’d noticed in the front hall snaked out, sharp and sickening.