1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

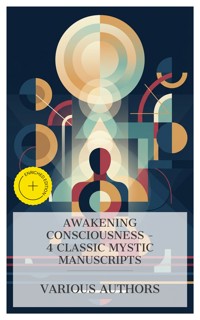

- Herausgeber: e-artnow Collections

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Awakening Consciousness – 4 Classic Mystic Manuscripts is a remarkable anthology that delves into the realms of mysticism, spirituality, and the search for inner truth. This collection brings together four seminal texts, each offering a distinctive take on the journey of enlightenment and self-discovery. The manuscripts range from insightful parables to profound philosophical discourses, collectively painting a rich canvas of human consciousness. Throughout the anthology, readers will uncover themes of divine wisdom, the nature of the soul, and the pursuit of spiritual harmony, all while engaging with thought-provoking literary styles that challenge the conventional boundaries of mystical literature. The anthology unites the visionary works of Mabel Collins, Levi H. Dowling, Joseph Benner, and U. G. Krishnamurti, each a luminary in their own right within the spiritual and mystical traditions. These authors, writing across a spectrum of time periods and cultural contexts, contribute uniquely to the anthology's vibrant tapestry of ideas and insights. Their works draw on historical and cultural movements, including Theosophy and New Thought, offering readers an expansive outlook on how mysticism can shape our understanding of the self and the universe. Awakening Consciousness is essential reading for anyone seeking to explore the depths of spiritual literature and mysticism through a diverse collection of voices. This anthology provides a unique opportunity to engage with the profound questions of existence crafted by its influential contributors. Whether for scholarly examination or personal reflection, the collection promises to enlighten readers, inviting them to partake in a profound dialogue across time and thought. Embrace this volume for its compelling narrative journey and the educational experience it offers into the realm of the mystical consciousness. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - An Introduction draws the threads together, discussing why these diverse authors and texts belong in one collection. - Historical Context explores the cultural and intellectual currents that shaped these works, offering insight into the shared (or contrasting) eras that influenced each writer. - A combined Synopsis (Selection) briefly outlines the key plots or arguments of the included pieces, helping readers grasp the anthology's overall scope without giving away essential twists. - A collective Analysis highlights common themes, stylistic variations, and significant crossovers in tone and technique, tying together writers from different backgrounds. - Reflection questions encourage readers to compare the different voices and perspectives within the collection, fostering a richer understanding of the overarching conversation.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Awakening Consciousness – 4 Classic Mystic Manuscripts

Table of Contents

Introduction

Awakening Consciousness – 4 Classic Mystic Manuscripts assembles works by Mabel Collins, Levi H. Dowling, Joseph Benner, and U. G. Krishnamurti around a single, insistent theme: the possibility of inner awakening. Each book seeks, in its own idiom, to loosen habitual certainties and invite a more luminous apprehension of life. The unifying thread is not doctrinal agreement but an experiential claim that awareness can be trained, shocked, or guided into a transformed clarity. Taken together, the texts propose that the journey of consciousness is both intimate and universal, requiring personal responsibility while pointing beyond private preference toward a wider, enduring reality.

Light on the Path and Through the Gates of Gold by Mabel Collins open the collection with images of guidance and passage. Their very titles suggest a pedagogy of light and a traversal of thresholds, presenting interior cultivation as a disciplined walk and a courageous crossing. The tone is concise and exhortatory, valuing attention, restraint, and purpose. In this approach, mystical aspiration is framed as practical training for perception and character. Collins provides a vocabulary of stages and qualities that anchor the more expansive or disruptive currents elsewhere in the volume, establishing a baseline of ethical poise and inward steadiness for readers to test and refine.

Levi H. Dowling’s The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ brings a narrative and devotional register into the conversation. Its gospel designation points to a storytelling mode in which teachings emerge through scenes, voices, and symbolic action. By centering a figure whose name carries profound resonance, the work integrates mystical insight with the cadence of a life-pattern, encouraging recognition of wisdom as embodied and enacted. The shift from aphoristic counsel to narrative movement expands the collection’s tonal range. It poses questions about authority, revelation, and universality that echo across the other works, without insisting on a single pathway or uniform vocabulary.

Joseph Benner’s The Impersonal Life introduces a rigorous interior emphasis, in which the deepest orientation is toward what the title names as impersonal. Here the problem of selfhood is recast as an obstacle to unclouded awareness, and devotion is redirected from personal assertion to a subtler alignment. The implied method is reflective, quiet, and uncompromising about motive. As a counterpoise to Dowling’s narrative and Collins’s practical directives, Benner’s focus concentrates attention on the source of agency and identity. The result is a searching meditation on responsibility and surrender, shaping a vision of freedom that neither denies the world nor accepts its claims unexamined.

U. G. Krishnamurti’s The Mystique of Enlightenment places the collection’s aspirations under unsparing scrutiny. The title signals a probing of the very idea of enlightenment as an alluring construct, with emphasis on exposing projection, romanticism, and spiritual ambition. The tone is bracing and iconoclastic, less concerned with offering techniques than with dismantling consoling narratives. In this voice, awakening is not a program but a confrontation with the unadorned fact of being, stripped of transferable models. Krishnamurti’s stance does not negate the other works; it interrogates their assumptions, forcing clarity about what is sought and why, and inviting sobriety where fervor might otherwise prevail.

Across these books, recurring motifs accumulate: path, gate, gospel, impersonality, enlightenment. Each term refracts the others, generating a productive dialogue about method and meaning. Collins cultivates disciplined ascent; Dowling narrates wisdom as event and character; Benner withdraws into a lucid interior axis; Krishnamurti questions the very premise of an attainable state. The shared dilemma is how to honor the urgency of transformation without substituting fantasy for insight or mere technique for understanding. Differences in tone—didactic, narrative, contemplative, skeptical—do not fracture the collection but articulate its breadth, revealing awakening as a family of approaches that correct, challenge, and sustain one another.

In contemporary culture, with its rapid circulation of symbols and persistent uncertainty about meaning, these works retain a distinctive resonance. Artists, thinkers, and seekers continue to debate whether consciousness can be educated, whether the sacred is personal or transpersonal, and whether enlightenment is achievable or illusory. The collection demonstrates that such questions are not exhausted by fashion, nor reducible to slogans. It models conversation across registers—ethical, imaginative, philosophical—without collapsing difference. As a result, the books operate as catalysts: they unsettle clichés, refine language for inner experience, and broaden the imaginative resources available to anyone exploring the life of awareness today.

Historical Context

Socio-Political Landscape

Composed in late-Victorian Britain, Mabel Collins’s Light on the Path and Through the Gates of Gold arise from an imperial society negotiating industrial expansion, class mobility, and gendered constraints. Their call to inner governance mirrors public anxieties about social order, vagrancy of belief, and the moral responsibilities of newly educated urban populations. Collins’s concise commandments and ascetic rhetoric implicitly valorize disciplined citizenship while questioning material triumphalism of empire. As a woman author in largely male esoteric forums, her voice also indexes broader suffrage-era tensions: the possibility of private spiritual authority challenging clerical, academic, and patriarchal gatekeeping without overt political agitation.

Levi H. Dowling’s The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ appears amid Progressive Era ferment in the United States, when labor conflict, temperance, and expanding suffrage reframed civic virtue. Its universalist Jesus, teaching across cultures, answers populist demands to democratize sacred authority beyond denominational lines. The book’s pacific cosmopolitanism responds to mounting militarism while affirming individual conscience over institutional decree. By presenting sacred history as an open, transnational itinerary, it subtly contests exclusivist nationalism and sectarian gatekeeping. The narrative’s stress on service and moral uplift dovetails with reformist currents that sought ethical reconstruction of society through transformed character rather than coercive regulation.

Joseph Benner’s The Impersonal Life meets readers in an America reeling from war, boom, and bust, where inward sovereignty offered refuge from volatile markets and fragile institutions. Its anonymous divine address decentralizes authority, promising stability amid civic disillusionment. Decades later, U. G. Krishnamurti’s The Mystique of Enlightenment confronts a globalized, postcolonial world skeptical of charismatic leadership and spiritual commerce. His uncompromising negations resonate with late twentieth‑century critiques of ideology, advertising, and guru economies. Together they chart a trajectory from solace within to demolition without: one proposes interior anchorage beyond politics, the other strips spiritual promises that, by then, mirrored consumer power structures.

Intellectual & Aesthetic Currents

Mabel Collins writes within the occult revival’s syncretic matrix, blending ascetic counsel with symbolic poetics. Light on the Path compresses wisdom into terse injunctions, adapting aphoristic forms recognizable from ancient sapiential literature while channeling meditative practices circulating in esoteric lodges. Through the Gates of Gold extends this economy of style into a reflective prose that privileges inner gold over outward acquisition, resonating with late‑Victorian aestheticism’s moralized refinement. Both works favor impersonal diction, ceremonial imagery, and disciplined cadence, cultivating a portable manual for self‑regulation. Their restrained rhetoric distances them from sensationalism, positioning mystic practice as sober craftsmanship rather than theatrical spectacle.

The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ synthesizes currents from American metaphysical religion, comparative philology, and spiritualist reportage. Its claim to recover teachings through visionary “records” exemplifies an era confident that science‑like methods could audit the invisible. Structurally, it remixes gospel pericopes with travel narrative, producing a pedagogical itinerary that humanizes, universalizes, and internationalizes Jesus. Stylistically plain yet programmatic, the text adopts didactic repetition and set‑piece discourses to model ethical formation. Its harmonizing theology aligns Christian motifs with broader wisdom traditions, mirroring a modernist hope that reconciliation of doctrines would accompany the reconciliation of peoples in a rapidly shrinking world.

Joseph Benner’s The Impersonal Life advances a radical second‑person address—“I” speaking as the divine within—that fuses New Thought affirmation, apophatic restraint, and nondual metaphysics. The effect is therapeutic minimalism: compressed sentences, gentle prohibitions, and recursive invitations to notice awareness itself. U. G. Krishnamurti’s The Mystique of Enlightenment counters with anti‑method: colloquial dialogues, uncompromising refusals, and physiological metaphors that de‑romanticize transcendence. Where Benner employs devotional intimacy to quiet striving, Krishnamurti dismantles the striver, indicting the cultural machinery that manufactures spiritual goals. Together they map a spectrum from interior consent to radical deconstruction, each using stark economy as rhetorical instrument.

Legacy & Reassessment Across Time

Mabel Collins’s manuals long circulated as initiation primers, prized for portability and severity; later readers have alternately praised their clarifying rigor and questioned hierarchical undertones. Scholarly reassessments read her work as a distinct female intervention in late‑Victorian esotericism, negotiating authority through stylistic austerity. The Aquarian Gospel has endured as an alternative scripture for seekers, fostering devotional communities and lay study circles. Critics scrutinize its historical claims and cultural projections, yet acknowledge its role in popularizing cross‑cultural ethics. Both authors’ texts oscillate between charges of simplification and recognition of pedagogical genius, sustaining debate over the proper balance between universality and context.

Joseph Benner’s The Impersonal Life has been repeatedly rediscovered during periods of spiritual self‑help enthusiasm, with readers debating whether its commanding inward “I” heals dependency or risks authoritarian substitution. Its anonymity invites projection, allowing communities to adapt it for contemplative practice without confessional boundary‑keeping. U. G. Krishnamurti’s The Mystique of Enlightenment circulates primarily as transcripts and quotations, shaping discourse through negation rather than program. Admirers find an ethical detox from spiritual consumerism; detractors hear sterile nihilism. Subsequent scholarship often pairs the two to illustrate a twentieth‑century swing between constructive interiorization and radical critique, each challenging institutional religion from divergent angles.

Synopsis (Selection)

Light on the Path and Through the Gates of Gold (Mabel Collins)

Two concise manuals outline the seeker’s ethical purification and perceptual refinement, using symbolic counsel to chart a movement from personal desire toward impersonal insight and poise.

Their prescriptive clarity aligns with Benner’s inward consecration and contrasts with U. G. Krishnamurti’s rejection of method, while Dowling’s mythic arc situates this roadmap within a universal story of awakening.

The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ (Levi H. Dowling)

An esoteric life of Jesus reframes the narrative as a universal itinerary of training and service, blending visionary instruction with a didactic, devotional tone.

Its expansive mythos amplifies Collins’s stepwise path and resonates with Benner’s inner divinity, even as its sacred narrative becomes a foil for U. G. Krishnamurti’s iconoclasm.

The Impersonal Life (Joseph Benner)

A meditative, admonitory discourse invites surrender of egoic striving to the impersonal divine within, emphasizing quiet receptivity and self-inquiry over external forms.

It echoes Collins’s purification while making the path immediate and inward, complementing Dowling’s universal Christ yet meeting the sharp skepticism of U. G. Krishnamurti’s anti-prescriptive stance.

The Mystique of Enlightenment (U. G. Krishnamurti)

A confrontational dismantling of spiritual ideals presents ‘enlightenment’ as no goal to pursue, challenging teachers, techniques, and transcendence as psychological traps.

Its radical negation cuts against the progressive maps of Collins, the devotional narrative of Dowling, and Benner’s inner surrender, sharpening the collection’s spectrum from structured aspiration to uncompromising critique.

Awakening Consciousness – 4 Classic Mystic Manuscripts

Esoteric Pathways and Symbolic Teaching

Impersonal Realization and Non‑dual Insight

Mabel Collins

Light on the Path and Through the Gates of Gold

LIGHT ON THE PATH

I

These rules are written for all disciples: Attend you to them.

Before the eyes can see, they must be incapable of tears. Before the ear can hear, it must have lost its sensitiveness. Before the voice can speak in the presence of the Masters it must have lost the power to wound. Before the soul can stand in the presence of the Masters its feet must be washed in the blood of the heart.

1. Kill out ambition.

2. Kill out desire of life.

3. Kill out desire of comfort.

4. Work as those work who are ambitious.

Respect life as those do who desire it. Be happy as those are who live for happiness.

Seek in the heart the source of evil and expunge it. It lives fruitfully in the heart of the devoted disciple as well as in the heart of the man of desire. Only the strong can kill it out. The weak must wait for its growth, its fruition, its death. And it is a plant that lives and increases throughout the ages. It flowers when the man has accumulated unto himself innumerable existences. He who will enter upon the path of power must tear this thing out of his heart. And then the heart will bleed, and the whole life of the man seem to be utterly dissolved. This ordeal must be endured: it may come at the first step of the perilous ladder which leads to the path of life: it may not come until the last. But, O disciple, remember that it has to be endured, and fasten the energies of your soul upon the task. Live neither in the present nor the future, but in the eternal. This giant weed cannot flower there: this blot upon existence is wiped out by the very atmosphere of eternal thought.

5. Kill out all sense of separateness.

6. Kill out desire for sensation.

7. Kill out the hunger for growth.

8. Yet stand alone and isolated, because nothing that is imbodied, nothing that is conscious of separation, nothing that is out of the eternal, can aid you. Learn from sensation and observe it, because only so can you commence the science of self-knowledge, and plant your foot on the first step of the ladder. Grow as the flower grows, unconsciously, but eagerly anxious to open its soul to the air. So must you press forward to open your soul to the eternal. But it must be the eternal that draws forth your strength and beauty, not desire of growth. For in the one case you develop in the luxuriance of purity, in the other you harden by the forcible passion for personal stature.

9. Desire only that which is within you.

10. Desire only that which is beyond you.

11. Desire only that which is unattainable.

12. For within you is the light of the world—the only light that can be shed upon the Path. If you are unable to perceive it within you, it is useless to look for it elsewhere. It is beyond you; because when you reach it you have lost yourself. It is unattainable, because it for ever recedes. You will enter the light, but you will never touch the flame.

13. Desire power ardently.

14. Desire peace fervently.

15. Desire possessions above all.

16. But those possessions must belong to the pure soul only, and be possessed therefore by all pure souls equally, and thus be the especial property of the whole only when united. Hunger for such possessions as can be held by the pure soul; that you may accumulate wealth for that united spirit of life, which is your only true self. The peace you shall desire is that sacred peace which nothing can disturb, and in which the soul grows as does the holy flower upon the still lagoons. And that power which the disciple shall covet is that which shall make him appear as nothing in the eyes of men.

17. Seek out the way.

18. Seek the way by retreating within.

19. Seek the way by advancing boldly without.

20. Seek it not by any one road. To each temperament there is one road which seems the most desirable. But the way is not found by devotion alone, by religious contemplation alone, by ardent progress, by self-sacrificing labor, by studious observation of life. None alone can take the disciple more than one step onward. All steps are necessary to make up the ladder. The vices of men become steps in the ladder, one by one, as they are surmounted. The virtues of man are steps indeed, necessary—not by any means to be dispensed with. Yet, though they create a fair atmosphere and a happy future, they are useless if they stand alone. The whole nature of man must be used wisely by the one who desires to enter the way. Each man is to himself absolutely the way, the truth, and the life. But he is only so when he grasps his whole individuality firmly, and, by the force of his awakened spiritual will, recognises this individuality as not himself, but that thing which he has with pain created for his own use, and by means of which he purposes, as his growth slowly develops his intelligence, to reach to the life beyond individuality. When he knows that for this his wonderful complex separated life exists, then, indeed, and then only, he is upon the way. Seek it by plunging into the mysterious and glorious depths of your own inmost being. Seek it by testing, all experience, by utilizing the senses in order to understand the growth and meaning of individuality, and the beauty and obscurity of those other divine fragments which are struggling side by side with you, and form the race to which you belong. Seek it by study of the laws of being, the laws of nature, the laws of the supernatural: and seek it by making the profound obeisance of the soul to the dim star that burns within. Steadily, as you watch and worship, its light will grow stronger. Then you may know you have found the beginning of the way. And when you have found the end its light will suddenly become the infinite light.

21. Look for the flower to bloom in the silence that follows the storm not till then.

It shall grow, it will shoot up, it will make branches and leaves and form buds, while the storm continues, while the battle lasts. But not till the whole personality of the man is dissolved and melted—not until it is held by the divine fragment which has created it, as a mere subject for grave experiment and experience—not until the whole nature has yielded and become subject unto its higher self, can the bloom open. Then will come a calm such as comes in a tropical country after the heavy rain, when Nature works so swiftly that one may see her action. Such a calm will come to the harassed spirit. And in the deep silence the mysterious event will occur which will prove that the way has been found. Call it by what name you will, it is a voice that speaks where there is none to speak—it is a messenger that comes, a messenger without form or substance; or it is the flower of the soul that has opened. It cannot be described by any metaphor. But it can be felt after, looked for, and desired, even amid the raging of the storm. The silence may last a moment of time or it may last a thousand years. But it will end. Yet you will carry its strength with you. Again and again the battle must be fought and won. It is only for an interval that Nature can be still.

These written above are the first of the rules which are written on the walls of the Hall of Learning. Those that ask shall have. Those that desire to read shall read. Those who desire to learn shall learn.

PEACE BE WITH YOU.

II

Out of the silence that is peace a resonant voice shall arise. And this voice will say, It is not well; thou hast reaped, now thou must sow. And knowing this voice to be the silence itself thou wilt obey.

Thou who art now a disciple, able to stand, able to hear, able to see, able to speak, who hast conquered desire and attained to self-knowledge, who hast seen thy soul in its bloom and recognised it, and heard the voice of the silence, go thou to the Hall of Learning and read what is written there for thee.

1. Stand aside in the coming battle, and though thou fightest be not thou the warrior.

2. Look for the warrior and let him fight in thee.

3. Take his orders for battle and obey them.

4. Obey him not as though he were a general, but as though he were thyself, and his spoken words were the utterance of thy secret desires; for he is thyself, yet infinitely wiser and stronger than thyself. Look for him, else in the fever and hurry of the fight thou mayest pass him; and he will not know thee unless thou knowest him. If thy cry meet his listening ear, then will he fight in thee and fill the dull void within. And if this is so, then canst thou go through the fight cool and unwearied, standing aside and letting him battle for thee. Then it will be impossible for thee to strike one blow amiss. But if thou look not for him, if thou pass him by, then there is no safeguard for thee. Thy brain will reel, thy heart grow uncertain, and in the dust of the battlefield thy sight and senses will fail, and thou wilt not know thy friends from thy enemies.

He is thyself, yet thou art but finite and liable to error. He is eternal and is sure. He is eternal truth. When once he has entered thee and become thy warrior, he will never utterly desert thee, and at the day of the great peace he will become one with thee.

5. Listen to the song of life.

6. Store in your memory the melody you hear.

7. Learn from it the lesson of harmony.

8. You can stand upright now, firm as a rock amid the turmoil, obeying the warrior who is thyself and thy king. Unconcerned in the battle save to do his bidding, having no longer any care as to the result of the battle, for one thing only is important, that the warrior shall win, and you know he is incapable of defeat—standing thus, cool and awakened, use the hearing you have acquired by pain and by the destruction of pain. Only fragments of the great song come to your ears while yet you are but man. But if you listen to it, remember it faithfully, so that none which has reached you is lost, and endeavor to learn from it the meaning of the mystery which surrounds you. In time you will need no teacher. For as the individual has voice, so has that in which the individual exists. Life itself has speech and is never silent. And its utterance is not, as you that are deaf may suppose, a cry: it is a song. Learn from it that you are part of the harmony; learn from it to obey the laws of the harmony.

9. Regard earnestly all the life that surrounds you.

10. Learn to look intelligently into the hearts of men.

11. Regard most earnestly your own heart.

12. For through your own heart comes the one light which can illuminate life and make it clear to your eyes.

Study the hearts of men, that you may know what is that world in which you live and of which you will to be a part. Regard the constantly changing and moving life which surrounds you, for it is formed by the hearts of men; and as you learn to understand their constitution and meaning, you will by degrees be able to read the larger word of life.

13. Speech comes only with knowledge. Attain to knowledge and you will attain to speech.

14. Having obtained the use of the inner senses, having conquered the desires of the outer senses, having conquered the desires of the individual soul, and having obtained knowledge, prepare now, O disciple, to enter upon the way in reality. The path is found: make yourself ready to tread it.

15. Inquire of the earth, the air, and the water, of the secrets they hold for you. The development of your inner senses will enable you to do this.

16. Inquire of the holy ones of the earth of the secrets they hold for you. The conquering of the desires of the outer senses will give you the right to do this.

17. Inquire of the inmost, the one, of its final secret which it holds for you through the ages.

The great and difficult victory, the conquering of the desires of the individual soul, is a work of ages; therefore expect not to obtain its reward until ages of experience have been accumulated. When the time of learning this seventeenth rule is reached, man is on the threshold of becoming more than man.

18. The knowledge which is now yours is only yours because your soul has become one with all pure souls and with the inmost. It is a trust vested in you by the Most High. Betray it, misuse your knowledge, or neglect it, and it is possible even now for you to fall from the high estate you have attained. Great ones fall back, even from the threshold, unable to sustain the weight of their responsibility, unable to pass on. Therefore look forward always with awe and trembling to this moment, and be prepared for the battle.

19. It is written that for him who is on the threshold of divinity no law can be framed, no guide can exist. Yet to enlighten the disciple, the final struggle may be thus expressed:

Hold fast to that which has neither substance nor existence.

20. Listen only to the voice which is soundless.

21. Look only on that which is invisible alike to the inner and the outer sense.

PEACE BE WITH YOU.

Footnote

Note on Rule 1.—Ambition is the first curse: the great tempter of the man who is rising above his fellows. It is the simplest form of looking for reward. Men of intelligence and power are led away from their higher possibilities by it continually. Yet it is a necessary teacher. Its results turn to dust and ashes in the mouth; like death and estrangement it shows the man at last that to work for self is to work for disappointment. But though this first rule seems so simple and easy, do not quickly pass it by. For these vices of the ordinary man pass through a subtle transformation and reappear with changed aspect in the heart of the disciple. It is easy to say, I will not be ambitious: it is not so easy to say, when the Master reads my heart he will find it clean utterly. The pure artist who works for the love of his work is sometimes more firmly planted on the right road than the occultist, who fancies he has removed his interest from self, but who has in reality only enlarged the limits of experience and desire, and transferred his interest to the things which concern his larger span of life. The same principle applies to the other two seemingly simple rules. Linger over them and do not let yourself be easily deceived by your own heart. For now, at the threshold, a mistake can be corrected. But carry it on with you and it will grow and come to fruition, or else you must suffer bitterly in its destruction.

Note on Rule 5.—Do not fancy you can stand aside from the bad man or the foolish man. They are yourself, though in a less degree than your friend or your master. But if you allow the idea of separateness from any evil thing or person to grow up within you, by so doing you create Karma, which will bind you to that thing or person till your soul recognises that it cannot be isolated. Remember that the sin and shame of the world are your sin and shame; for you are a part of it; your Karma is inextricably interwoven with the great Karma. And before you can attain knowledge you must have passed through all places, foul and clean alike. Therefore, remember that the soiled garment you shrink from touching may have been yours yesterday, may be yours tomorrow. And if you turn with horror from it, when it is flung upon your shoulders, it will cling the more closely to you. The self-righteous man makes for himself a bed of mire. Abstain because it is right to abstain—not that yourself shall be kept clean.

Note on Rule 17.—These four words seem, perhaps, too slight to stand alone. The disciple may say, Should I study these thoughts at all did I not seek out the way? Yet do not pass on hastily. Pause and consider awhile. Is it the way you desire, or is it that there is a dim perspective in your visions of great heights to be scaled by yourself, of a great future for you to compass? Be warned. The way is to be sought for its own sake, not with regard to your feet that shall tread it.

There is a correspondence between this rule and the 17th of the 2nd series. When after ages of struggle and many victories the final battle is won, the final secret demanded, then you are prepared for a further path. When the final secret of this great lesson is told, in it is opened the mystery of the new way—a path which leads out of all human experience, and which is utterly beyond human perception or imagination. At each of these points it is needful to pause long and consider well. At each of these points it is necessary to be sure that the way is chosen for its own sake. The way and the truth come first, then follows the life.

Note on Rule 20.—Seek it by testing all experience, and remember that when I say this I do not say, Yield to the seductions of sense in order to know it. Before you have become an occultist you may do this; but not afterwards. When you have chosen and entered the path you cannot yield to these seductions without shame. Yet you can experience them without horror: can weigh, observe and test them, and wait with the patience of confidence for the hour when they shall affect you no longer. But do not condemn the man that yields; stretch out your hand to him as a brother pilgrim whose feet have become heavy with mire. Remember, O disciple, that great though the gulf may be between the good man and the sinner, it is greater between the good man and the man who has attained knowledge; it is immeasurable between the good man and the one on the threshold of divinity. Therefore be wary lest too soon you fancy yourself a thing apart from the mass. When you have found the beginning of the way the star of your soul will show its light; and by that light you will perceive how great is the darkness in which it burns. Mind, heart, brain, all are obscure and dark until the first great battle has been won. Be not appalled and terrified by this sight; keep your eyes fixed on the small light and it will grow. But let the darkness within help you to understand the helplessness of those who have seen no light, whose souls are in profound gloom. Blame them not, shrink not from them, but try to lift a little of the heavy Karma of the world; give your aid to the few strong hands that hold back the powers of darkness from obtaining complete victory. Then do you enter into a partnership of joy, which brings indeed terrible toil and profound sadness, but also a great and ever-increasing delight.

Note on Rule 21.—The opening of the bloom is the glorious moment when perception awakes: with it comes confidence, knowledge, certainty. The pause of the soul is the moment of wonder, and the next moment of satisfaction, that is the silence.

Know, O disciple, that those who have passed through the silence, and felt its peace and retained its strength, they long that you shall pass through it also. Therefore, in the Hall of Learning, when he is capable of entering there, the disciple will always find his master.

Those that ask shall have. But though the ordinary man asks perpetually, his voice is not heard. For he asks with his mind only; and the voice of the mind is only heard on that plane on which the mind acts. Therefore, not until the first twenty-one rules are past do I say those that ask shall have.

To read, in the occult sense, is to read with the eyes of the spirit. To ask is to feel the hunger within—the yearning of spiritual aspiration. To be able to read means having obtained the power in a small degree of gratifying that hunger. When the disciple is ready to learn, then he is accepted, acknowledged, recognised. It must be so, for he has lit his lamp, and it cannot be hidden. But to learn is impossible until the first great battle has been won. The mind may recognise truth, but the spirit cannot receive it. Once having passed through the storm and attained the peace, it is then always possible to learn, even though the disciple waver, hesitate, and turn aside. The voice of the silence remains within him, and though he leave the path utterly, yet one day it will resound and rend him asunder and separate his passions from his divine possibilities. Then with pain and desperate cries from the deserted lower self he will return.

Therefore I say, Peace be with you. My peace I give unto you can only be said by the Master to the beloved disciples who are as himself. There are even some amongst those who are ignorant of the Eastern wisdom to whom this can be said, and to whom it can daily be said with more completeness.

Regard the three truths. They are equal.

PART II

Note on Sect. II—To be able to stand is to have confidence; to be able to hear is to have opened the doors of the soul; to be able to see is to have attained perception; to be able to speak is to have attained the power of helping others; to have conquered desire is to have learned how to use and control the self; to have attained to self-knowledge is to have retreated to the inner fortress from whence the personal man can be viewed with impartiality; to have seen thy soul in its bloom is to have obtained a momentary glimpse in thyself of the transfiguration which shall eventually make thee more than man; to recognise is to achieve the great task of gazing upon the blazing light without dropping the eyes and not falling back in terror, as though before some ghastly phantom. This happens to some, and so when the victory is all but won it is lost; to hear the voice of the silence is to understand that from within comes the only true guidance; to go to the Hall of Learning is to enter the state in which learning becomes possible. Then will many words be written there for thee, and written in fiery letters for thee easily to read. For when the disciple is ready the Master is ready also.

Note on Rule 5.—Look for it and listen to it first in your own heart. At first you may say it is not there; when I search I find only discord. Look deeper. If again you are disappointed, pause and look deeper again. There is a natural melody, an obscure fount in every human heart. It may be hidden over and utterly concealed and silenced—but it is there. At the very base of your nature you will find faith, hope, and love. He that chooses evil refuses to look within himself, shuts his ears to the melody of his heart, as he blinds his eyes to the light of his soul. He does this because he finds it easier to live in desires. But underneath all life is the strong current that cannot be checked; the great waters are there in reality. Find them, and you will perceive that none, not the most wretched of creatures, but is a part of it, however he blind himself to the fact and build up for himself a phantasmal outer form of horror. In that sense it is that I say to you—All those beings among whom you struggle on are fragments of the Divine. And so deceptive is the illusion in which you live, that it is hard to guess where you will first detect the sweet voice in the hearts of others.

But know that it is certainly within yourself. Look for it there, and once having heard it, you will more readily recognise it around you.

Note on Rule 10.—From an absolutely impersonal point of view, otherwise your sight is colored. Therefore impersonality must first be understood.

Intelligence is impartial: no man is your enemy: no man is your friend. All alike are your teachers. Your enemy becomes a mystery that must be solved, even though it take ages: for man must be understood. Your friend becomes a part of yourself, an extension of yourself, a riddle hard to read. Only one thing is more difficult to know—your own heart. Not until the bonds of personality are loosed, can that profound mystery of self begin to be seen. Not till you stand aside from it will it in any way reveal itself to your understanding. Then, and not till then, can you grasp and guide it. Then, and not till then, can you use all its powers, and devote them to a worthy service.

Note on Rule 13.—It is impossible to help others till you have obtained some certainty of your own. When you have learned the first 21 rules and have entered the Hall of Learning with your powers developed and sense unchained, then you will find there is a fount within you from which speech will arise.

After the 13th rule I can add no words to what is already written.

My peace I give unto you. [Greek: D]

These notes are written only for those to whom I give my peace; those who can read what I have written with the inner as well as the outer sense.

COMMENTS

I

"BEFORE THE EYES CAN SEE THEY MUST BE INCAPABLE OF TEARS."

It should be very clearly remembered by all readers of this volume that it is a book which may appear to have some little philosophy in it, but very little sense, to those who believe it to be written in ordinary English. To the many, who read in this manner it will be—not caviare so much as olives strong of their salt. Be warned and read but a little in this way.

There is another way of reading, which is, indeed, the only one of any use with many authors. It is reading, not between the lines but within the words. In fact, it is deciphering a profound cipher. All alchemical works are written in the cipher of which I speak; it has been used by the great philosophers and poets of all time. It is used systematically by the adepts in life and knowledge, who, seemingly giving out their deepest wisdom, hide in the very words which frame it its actual mystery. They cannot do more. There is a law of nature which insists that a man shall read these mysteries for himself. By no other method can he obtain them. A man who desires to live must eat his food himself: this is the simple law of nature—which applies also to the higher life. A man who would live and act in it cannot be fed like a babe with a spoon; he must eat for himself.

I propose to put into new and sometimes plainer language parts of "Light on the Path"; but whether this effort of mine will really be any interpretation I cannot say. To a deaf and dumb man, a truth is made no more intelligible if, in order to make it so, some misguided linguist translates the words in which it is couched into every living or dead language, and shouts these different phrases in his ear. But for those who are not deaf and dumb one language is generally easier than the rest; and it is to such as these I address myself.

The very first aphorisms of "Light on the Path," included under Number I, have, I know well, remained sealed as to their inner meaning to many who have otherwise followed the purpose of the book.

There are four proven and certain truths with regard to the entrance to occultism. The Gates of Gold bar that threshold; yet there are some who pass those gates and discover the sublime and illimitable beyond. In the far spaces of Time all will pass those gates. But I am one who wish that Time, the great deluder, were not so over-masterful. To those who know and love him I have no word to say; but to the others—and there are not so very few as some may fancy—to whom the passage of Time is as the stroke of a sledge-hammer, and the sense of Space like the bars of an iron cage, I will translate and re-translate until they understand fully.

The four truths written on the first page of "Light on the Path," refer to the trial initiation of the would-be occultist. Until he has passed it, he cannot even reach to the latch of the gate which admits to knowledge. Knowledge is man's greatest inheritance; why, then, should he not attempt to reach it by every possible road? The laboratory is not the only ground for experiment; science, we must remember, is derived from sciens, present participle of scire, "to know,"—its origin is similar to that of the word "discern," to "ken." Science does not therefore deal only with matter, no, not even its subtlest and obscurest forms. Such an idea is born merely of the idle spirit of the age. Science is a word which covers all forms of knowledge. It is exceedingly interesting to hear what chemists discover, and to see them finding their way through the densities of matter to its finer forms; but there are other kinds of knowledge than this, and it is not every one who restricts his (strictly scientific) desire for knowledge to experiments which are capable of being tested by the physical senses.

Everyone who is not a dullard, or a man stupefied by some predominant vice, has guessed or even perhaps discovered with some certainty, that there are subtle senses lying within the physical senses. There is nothing at all extraordinary in this; if we took the trouble to call Nature into the witness box we should find that everything which is perceptible to the ordinary sight, has something even more important than itself hidden within it; the microscope has opened a world to us, but within those encasements which the microscope reveals, lies a mystery which no machinery can probe.

The whole world is animated and lit, down to its most material shapes, by a world within it. This inner world is called Astral by some people, and it is as good a word as any other, though it merely means starry; but the stars, as Locke pointed out, are luminous bodies which give light of themselves. This quality is characteristic of the life which lies within matter; for those who see it, need no lamp to see it by. The word star, moreover, is derived from the Anglo-Saxon "stir-an," to steer, to stir, to move, and undeniably it is the inner life which is master of the outer, just as a man's brain guides the movements of his lips. So that although Astral is no very excellent word in itself, I am content to use it for my present purpose.

The whole of "Light on the Path" is written in an astral cipher and can therefore only be deciphered by one who reads astrally. And its teaching is chiefly directed towards the cultivation and development of the astral life. Until the first step has been taken in this development, the swift knowledge, which is called intuition with certainty, is impossible to man. And this positive and certain intuition is the only form of knowledge which enables a man to work rapidly or reach his true and high estate, within the limit of his conscious effort. To obtain knowledge by experiment is too tedious a method for those who aspire to accomplish real work; he who gets it by certain intuition, lays hands on its various forms with supreme rapidity, by fierce effort of will; as a determined workman grasps his tools, indifferent to their weight or any other difficulty which may stand in his way. He does not stay for each to be tested—he uses such as he sees are fittest.

All the rules contained in "Light on the Path," are written for all disciples, but only for disciples—-those who "take knowledge." To none else but the student in this school are its laws of any use or interest.

To all who are interested seriously in Occultism, I say first—take knowledge. To him who hath shall be given. It is useless to wait for it. The womb of Time will close before you, and in later days you will remain unborn, without power. I therefore say to those who have any hunger or thirst for knowledge, attend to these rules.

They are none of my handicraft or invention. They are merely the phrasing of laws in super-nature, the putting into words truths as absolute in their own sphere, as those laws which govern the conduct of the earth and its atmosphere.

The senses spoken of in these four statements are the astral, or inner senses.

No man desires to see that light which illumines the spaceless soul until pain and sorrow and despair have driven him away from the life of ordinary humanity. First he wears out pleasure; then he wears out pain—till, at last, his eyes become incapable of tears.

This is a truism, although I know perfectly well that it will meet with a vehement denial from many who are in sympathy with thoughts which spring from the inner life. To see with the astral sense of sight is a form of activity which it is difficult for us to understand immediately. The scientist knows very well what a miracle is achieved by each child that is born into the world, when it first conquers its eyesight and compels it to obey its brain. An equal miracle is performed with each sense certainly, but this ordering of sight is perhaps the most stupendous effort. Yet the child does it almost unconsciously, by force of the powerful heredity of habit. No one now is aware that he has ever done it at all; just as we cannot recollect the individual movements which enabled us to walk up a hill a year ago. This arises from the fact that we move and live and have our being in matter. Our knowledge of it has become intuitive.

With our astral life it is very much otherwise. For long ages past, man has paid very little attention to it—so little, that he has practically lost the use of his senses. It is true, that in every civilization the star arises, and man confesses, with more or less of folly and confusion, that he knows himself to be. But most often he denies it, and in being a materialist becomes that strange thing, a being which cannot see its own light, a thing of life which will not live, an astral animal which has eyes, and ears, and speech, and power, yet will use none of these gifts. This is the case, and the habit of ignorance has become so confirmed, that now none will see with the inner vision till agony has made the physical eyes not only unseeing, but without tears—the moisture of life. To be incapable of tears is to have faced and conquered the simple human nature, and to have attained an equilibrium which cannot be shaken by personal emotions. It does not imply any hardness of heart, or any indifference. It does not imply the exhaustion of sorrow, when the suffering soul seems powerless to suffer acutely any longer; it does not mean the deadness of old age, when emotion is becoming dull because the strings which vibrate to it are wearing out. None of these conditions are fit for a disciple, and if any one of them exist in him it must be overcome before the path can be entered upon. Hardness of heart belongs to the selfish man, the egotist, to whom the gate is forever closed. Indifference belongs to the fool and the false philosopher; those whose lukewarmness makes them mere puppets, not strong enough to face the realities of existence. When pain or sorrow has worn out the keenness of suffering, the result is a lethargy not unlike that which accompanies old age, as it is usually experienced by men and women. Such a condition makes the entrance to the path impossible, because the first step is one of difficulty and needs a strong man, full of psychic and physical vigor, to attempt it.

It is a truth, that, as Edgar Allan Poe said, the eyes are the windows for the soul, the windows of that haunted palace in which it dwells. This is the very nearest interpretation into ordinary language of the meaning of the text. If grief, dismay, disappointment or pleasure, can shake the soul so that it loses its fixed hold on the calm spirit which inspires it, and the moisture of life breaks forth, drowning knowledge in sensation, then all is blurred, the windows are darkened, the light is useless. This is as literal a fact as that if a man, at the edge of a precipice, loses his nerve through some sudden emotion he will certainly fall. The poise of the body, the balance, must be preserved, not only in dangerous places, but even on the level ground, and with all the assistance Nature gives us by the law of gravitation. So it is with the soul, it is the link between the outer body and the starry spirit beyond; the divine spark dwells in the still place where no convulsion of Nature can shake the air; this is so always. But the soul may lose its hold on that, its knowledge of it, even though these two are part of one whole; and it is by emotion, by sensation, that this hold is loosed. To suffer either pleasure or pain, causes a vivid vibration which is, to the consciousness of man, life. Now this sensibility does not lessen when the disciple enters upon his training; it increases. It is the first test of his strength; he must suffer, must enjoy or endure, more keenly than other men, while yet he has taken on him a duty which does not exist for other men, that of not allowing his suffering to shake him from his fixed purpose. He has, in fact, at the first step to take himself steadily in hand and put the bit into his own mouth; no one else can do it for him.

The first four aphorisms of "Light on the Path," refer entirely to astral development. This development must be accomplished to a certain extent—that is to say it must be fully entered upon—before the remainder of the book is really intelligible except to the intellect; in fact, before it can be read as a practical, not a metaphysical treatise.

In one of the great mystic Brotherhoods, there are four ceremonies, that take place early in the year, which practically illustrate and elucidate these aphorisms. They are ceremonies in which only novices take part, for they are simply services of the threshold. But it will show how serious a thing it is to become a disciple, when it is understood that these are all ceremonies of sacrifice. The first one is this of which I have been speaking. The keenest enjoyment, the bitterest pain, the anguish of loss and despair, are brought to bear on the trembling soul, which has not yet found light in the darkness, which is helpless as a blind man is, and until these shocks can be endured without loss of equilibrium the astral senses must remain sealed. This is the merciful law. The "medium," or "spiritualist," who rushes into the psychic world without preparation, is a law-breaker, a breaker of the laws of super-nature. Those who break Nature's laws lose their physical health; those who break the laws of the inner life, lose their psychic health. "Mediums" become mad, suicides, miserable creatures devoid of moral sense; and often end as unbelievers, doubters even of that which their own eyes have seen. The disciple is compelled to become his own master before he adventures on this perilous path, and attempts to face those beings who live and work in the astral world, and whom we call masters, because of their great knowledge and their ability to control not only themselves but the forces around them.

The condition of the soul when it lives for the life of sensation as distinguished from that of knowledge, is vibratory or oscillating, as distinguished from fixed. That is the nearest literal representation of the fact; but it is only literal to the intellect, not to the intuition. For this part of man's consciousness a different vocabulary is needed. The idea of "fixed" might perhaps be transposed into that of "at home." In sensation no permanent home can be found, because change is the law of this vibratory existence. That fact is the first one which must be learned by the disciple. It is useless to pause and weep for a scene in a kaleidoscope which has passed.

It is a very well-known fact, one with which Bulwer Lytton dealt with great power, that an intolerable sadness is the very first experience of the neophyte in Occultism. A sense of blankness falls upon him which makes the world a waste, and life a vain exertion. This follows his first serious contemplation of the abstract. In gazing, or even in attempting to gaze, on the ineffable mystery of his own higher nature, he himself causes the initial trial to fall on him. The oscillation between pleasure and pain ceases for—perhaps an instant of time; but that is enough to have cut him loose from his fast moorings in the world of sensation. He has experienced, however briefly, the greater life; and he goes on with ordinary existence weighted by a sense of unreality, of blank, of horrid negation. This was the nightmare which visited Bulwer Lytton's neophyte in "Zanoni"; and even Zanoni himself, who had learned great truths, and been entrusted with great powers, had not actually passed the threshold where fear and hope, despair and joy seem at one moment absolute realities, at the next mere forms of fancy.

This initial trial is often brought on us by life itself. For life is after all, the great teacher. We return to study it, after we have acquired power over it, just as the master in chemistry learns more in the laboratory than his pupil does. There are persons so near the door of knowledge that life itself prepares them for it, and no individual hand has to invoke the hideous guardian of the entrance. These must naturally be keen and powerful organizations, capable of the most vivid pleasure; then pain comes and fills its great duty. The most intense forms of suffering fall on such a nature, till at last it arouses from its stupor of consciousness, and by the force of its internal vitality steps over the threshold into a place of peace. Then the vibration of life loses its power of tyranny. The sensitive nature must suffer still; but the soul has freed itself and stands aloof, guiding the life towards its greatness. Those who are the subjects of Time, and go slowly through all his spaces, live on through a long drawn series of sensations, and suffer a constant mingling of pleasure and of pain. They do not dare to take the snake of self in a steady grasp and conquer it, so becoming divine; but prefer to go on fretting through divers experiences, suffering blows from the opposing forces.

When one of these subjects of Time decides to enter on the path of Occultism, it is this which is his first task. If life has not taught it to him, if he is not strong enough to teach himself and if he has power enough to demand the help of a master, then this fearful trial, depicted in Zanoni, is put upon him. The oscillation in which he lives, is for an instant stilled; and he has to survive the shock of facing what seems to him at first sight as the abyss of nothingness. Not till he has learned to dwell in this abyss, and has found its peace, is it possible for his eyes to have become incapable of tears.

II

"BEFORE THE EAR CAN HEAR, IT MUST HAVE LOST ITS SENSITIVENESS."

The first four rules of "Light on the Path" are, undoubtedly, curious though the statement may seem, the most important in the whole book, save one only. Why they are so important is that they contain the vital law, the very creative essence of the astral man. And it is only in the astral (or self-illuminated) consciousness that the rules which follow them have any living meaning. Once attain to the use of the astral senses and it becomes a matter of course that one commences to use them; and the later rules are but guidance in their use. When I speak like this I mean, naturally, that the first four rules are the ones which are of importance and interest to those who read them in print upon a page. When they are engraved on a man's heart and on his life, unmistakably then the rules become not merely interesting, or extraordinary, metaphysical statements, but actual facts in life which have to be grasped and experienced.

The four rules stand written in the great chamber of every actual lodge of a living Brotherhood. Whether the man is about to sell his soul to the devil, like Faust; whether he is to be worsted in the battle, like Hamlet; or whether he is to pass on within the precincts; in any case these words are for him. The man can choose between virtue and vice, but not until he is a man; a babe or a wild animal cannot so choose. Thus with the disciple, he must first become a disciple before he can even see the paths to choose between. This effort of creating himself as a disciple, the re-birth, he must do for himself without any teacher. Until the four rules are learned no teacher can be of any use to him; and that is why "the Masters" are referred to in the way they are. No real masters, whether adepts in power, in love, or in blackness, can affect a man till these four rules are passed.

Tears, as I have said, may be called the moisture of life. The soul must have laid aside the emotions of humanity, must have secured a balance which cannot be shaken by misfortune, before its eyes can open upon the super-human world.

The voice of the Masters is always in the world; but only those hear it whose ears are no longer receptive of the sounds which affect the personal life. Laughter no longer lightens the heart, anger may no longer enrage it, tender words bring it no balm. For that within, to which the ears are as an outer gateway, is an unshaken place of peace in itself which no person can disturb.

As the eyes are the windows of the soul, so are the ears its gateways or doors. Through them comes knowledge of the confusion of the world. The great ones who have conquered life, who have become more than disciples, stand at peace and undisturbed amid the vibration and kaleidoscopic movement of humanity. They hold within themselves a certain knowledge, as well as a perfect peace; and thus they are not roused or excited by the partial and erroneous fragments of information which are brought to their ears by the changing voices of those around them. When I speak of knowledge, I mean intuitive knowledge. This certain information can never be obtained by hard work, or by experiment; for these methods are only applicable to matter, and matter is in itself a perfectly uncertain substance, continually affected by change. The most absolute and universal laws of natural and physical life, as understood by the scientist, will pass away when the life of this universe has passed away, and only its soul is left in the silence. What then will be the value of the knowledge of its laws acquired by industry and observation? I pray that no reader or critic will imagine that by what I have said I intend to depreciate or disparage acquired knowledge, or the work of scientists. On the contrary, I hold that scientific men are the pioneers of modern thought. The days of literature and of art, when poets and sculptors saw the divine light, and put it into their own great language—these days lie buried in the long past with the ante-Phidian sculptors and the pre-Homeric poets. The mysteries no longer rule the world of thought and beauty; human life is the governing power, not that which lies beyond it. But the scientific workers are progressing, not so much by their own will as by sheer force of circumstances, towards the far line which divides things interpretable from things uninterpretable. Every fresh discovery drives them a step onward. Therefore do I very highly esteem the knowledge obtained by work and experiment.

But intuitive knowledge is an entirely different thing. It is not acquired in any way, but is, so to speak, a faculty of the soul; not the animal soul, that which becomes a ghost after death, when lust or liking or the memory of ill deeds holds it to the neighborhood of human beings, but the divine soul which animates all the external forms of the individualized being.

This is, of course, a faculty which indwells in that soul, which is inherent. The would-be disciple has to arouse himself to the consciousness of it by a fierce and resolute and indomitable effort of will. I use the word indomitable for a special reason. Only he who is untameable, who cannot be dominated, who knows he has to play the lord over men, over facts, over all things save his own divinity can arouse this faculty. "With faith all things, are possible." The skeptical laugh at faith and pride themselves on its absence from their own minds. The truth is that faith is a great engine, an enormous power, which in fact can accomplish all things. For it is the convenant or engagement between man's divine part and his lesser self.

The use of this engine is quite necessary in order to obtain intuitive knowledge; for unless a man believes such knowledge exists within himself how can he claim and use it?

Without it he is more helpless than any drift-wood or wreckage on the great tides of the ocean. They are cast hither and thither indeed; so may a man be by the chances of fortune. But such adventures are purely external and of very small account. A slave may be dragged through the streets in chains, and yet retain the quiet soul of a philosopher, as was well seen in the person of Epictetus. A man may have every worldly prize in his possession, and stand absolute master of his personal fate, to all appearance, and yet he knows no peace, no certainty, because he is shaken within himself by every tide of thought that he touches on. And these changing tides do not merely sweep the man bodily hither and thither like drift-wood on the water; that would be nothing. They enter into the gate-ways of his soul, and wash over that soul and make it blind and blank and void of all permanent intelligence so that passing impressions affect it.