3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Imaginarium Kim

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

“Band 2” is a chronological collection of previously published short stories by Ithaka O.

- - -

List of stories in this collection

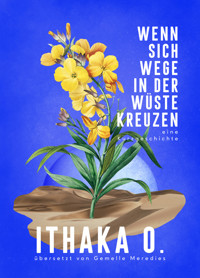

- When Paths Cross In the Desert

- The Fortune of the Palms

- When the Closet Worked Its Magic

- Milk

- Baby Blue

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

BAND 2

A CHRONOLOGICAL COLLECTION

ITHAKA WROTE SHORTS

ITHAKA O.

IMAGINARIUM KIM

© 2023 Ithaka O.

All rights reserved.

This story is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

No part of this story may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author.

CONTENTS

When Paths Cross In the Desert

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

The Fortune of the Palms

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

When the Closet Worked Its Magic

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Milk

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Baby Blue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Also by Ithaka O.

Thank you for reading

WHEN PATHS CROSS IN THE DESERT

1

The first time someone knocks from the other side, you look up. It’s the natural reaction, one that your grandmother before you and her grandmother before her have gotten from her grandmother who came way before them, so they can survive. Looking in the direction of a sound: a simple way to make sure you see your enemy, who might bludgeon you to death to take what’s rightfully yours. Then you can fight, flight, freeze—whichever you prefer or are capable of doing. Simple.

But this was no natural situation. From here, I couldn’t take flight. From here, we couldn’t fight. I could freeze, sure. But there was no reason to, because no one could bludgeon me to death. I was very aware of that. I had made myself be aware of that over many months, so that when someone knocked from the other side, I didn’t look up.

I had thought I had mastered this bitter trick. I watered the sweet little solitary yellow flower while the person kept knocking on the glass to get my attention. “The person,” because I resolutely refused to notice whether they were male, female, old, or young.

Here was how you did it. You looked down. Concentrated on the delicate oblong petals. Watched how, even when you aimed the narrow, quite precise stream of water right at the root of the flower, some of the water bounced off the arid ground. It behaved like extremely dry skin. You could put all the best moisturizing creams you wanted, it would still hurt and refuse to absorb most of the good ingredients, because it wasn’t functioning as it should. Such skin was broken. So was this ground. With its cracks so deep I couldn’t see the bottom, sometimes it just spat the water droplets right back out instead of letting them seep in.

Anyway, you looked down and watched the water and the flower. Admired the beautifully elegant curve of your copper watering can. Wondered that, had you been more interested in flowers and plants in general before the world came to this, if there would’ve been more little yellow flowers on this side, so this one here wouldn’t look so lonely. Or perhaps the seed of this particular yellow flower would’ve miraculously sensed that you were blessed with a green thumb, and would’ve grown closer to the home dome instead of the edge of the outer dome. In that case, since the home dome and outer dome were concentric, I could’ve stayed away from the madman (damn it, now I knew he was a man, I could see he was wearing running shoes as huge as boats, his ankles hairy) as far as physically possible. Then he might not have spotted me and then I wouldn’t have had to try so hard to keep looking down, concentrating on the stream of fresh, pleasantly cool water, landing at the root of the little yellow flower, to sometimes be absorbed and most of the time to bounce off.

He had to be a madman. Otherwise, why was he still knocking like crazy on the glass of the outer dome? They say a person who keeps doing the same thing over and over again, expecting a different result, is mad. By now, the knocking had become more than a sound: it traveled from his side to my side in the form of a dull prickling that made the hair on my bare arms stand on end. Sound and its waves—they knew no barriers. Even a shield as strong as the outer dome couldn’t fully block them out when someone hit it directly. Even this extra-fortified glass had to react to its surroundings. It, unlike me, couldn’t resolutely opt for ignorance.

“Water!” said the madman.

His voice sounded muffled. If it hadn’t been so obvious that he would utter that word, I might not have understood it.

“Please! We need more!”

Also obvious words.

Oh, how glad I was that Timothy had had the good sense to build these domes! About a year ago—eons ago—everyone told him he was crazy. A fortified glass dome in the middle of the desert! The size of a baseball stadium, too! And another littler dome inside, that one not transparent but black for privacy and for double protection! Protection from what? What a waste of resources. Crazy billionaire engineer. Thinks he’s the real Iron Man or something, when in reality, he’s just a paranoid doomsday advocate.

For the record, the outer dome was only as large as the actual field part of a baseball stadium—so, not including the seats.

Also, well, surprise, surprise. This was the reality. Most of the naysayers had all died. And I was here, in this glorious haven, where the strongest of the cruel sun’s rays got filtered and softened by Timothy’s special glass. No matter where the sun was, it never hurt my eyes. The air here, though dry and always rough in my nostrils, wasn’t nearly as dry and rough as the air outside. Or so I imagined. I’d never had to check first-hand. But in the beginning, before I had mastered my bitter trick, I had made the mistake of looking up. Multiple times. The skin condition of those outside told me that no moisturizing cream could fix them. Ever.

While the world outside roasted in Eternal Summer, hotter but more cold-blooded than any other summer ever witnessed in human history, I was watering a little yellow flower whose name I didn’t know. Our massive air conditioners circulated the air inside the outer dome. Less massive air conditioners circulated the air inside the home dome. I could wear a tank top, braless, showing my bare arms, because I didn’t need to worry about keeping the little moisture that I had inside my body. Truly, what I was doing by showing up here in my shorts and flip-flops was flaunting my luxury.

Why? I don’t know. Some of it was wanting to give those people out there a chance to yell at me, the way the madman was doing now. They always did, so I assumed they didn’t hate it. We all needed something to do, some kind of a routine that marked the day’s arrival and passing. The watering of the little yellow flower was a special event that served that function. That was why I, too, acted like a madperson by coming here every day, overcoming the fear that one day, I might run out of water and regret ever having watered the little yellow flower. A weird sense of obligation had formed inside me—to the flower and to those people.

Why did they keep approaching me? Why didn’t they hate me? I deserved their hatred. Whether massive or not, the air conditioners in the domes all released scorching steam into the atmosphere outside. But I was inside and look, obviously I didn’t care.

My reluctance, no, unwillingness to help should have been obvious. What was inside trumped all that was outside—the little yellow flower, for example, which never would’ve bloomed had it not been for Timothy’s foresight. We were inside, while a madman in boat-sized running shoes knocked from the other side, mad because he hadn’t seen water for days, possibly weeks. If I were to look up now, I could probably determine whether it was days or weeks. But I didn’t. This wasn’t nature. It was pointless. I wasn’t going to take flight. I wasn’t going to fight. I didn’t need to freeze. I, as an individual, had done absolutely nothing wrong. I hadn’t triggered Eternal Summer.

The narrow stream of water ceased to come out of my pretty copper watering can. Briefly, the madman’s knocking stopped. It was this sudden lack of sound and waves that made me forget about my bitter trick.

I made a mistake. I looked up.

The madman’s eyes were so grotesque, I suppressed a flinch. They were hollow. Because of that void, they looked like they could hold everything in this world. Water, massive amounts of water, whole bodies of water, ponds and rivers and lakes and oceans, if they were available. Or maybe not. Not enough room for water, because there was so much despair filling his eyes already. In that case, there was no void. In this whole wide world, so much despair was available, so there was no room for a void.

Once upon a time, those eyes may have sparkled with life. It was hard to tell his age. Maybe about the same as me, late twenties, early thirties. But when the sun shriveled you up, the young ones looked decades older all the time. And the older ones died without a chance to look even older.

Behind the madman crowded dozens more madpeople. Some sat, some lay. A few stood, in apparent solidarity with the madman. Everyone wore long-sleeved clothes. Many had thrown clothes over their heads. Those who hadn’t were going to terribly regret it later. The heat haze shimmered all around them. There was no roof. These were people who had left the town areas, having heard about the miraculous dome in the middle of the desert. Some had given up hoping for a way back. Some among those who lay were probably already dead.

Dozens. And beyond them, hundreds.

In the first days of Eternal Summer, the horizon had been free of all obstacles except for a solitary half-built pale-brown structure of some kind. (A collapsing phone booth? a random elevator? a giant abandoned water pipe, from a time when it used to rain and large water-cleaning facilities still served the populace instead of a few of the superrich?) So, I assumed that the additional bumps and lumps presently visible were all human or animal. There were no plants. If there had been, this wouldn’t be called Eternal Summer. Actually, that name was euphemistic. It should’ve been called Eternal Hell, Eternal Inferno, something more dramatic like that. But in the beginning, nobody had wanted to believe it was going to be hell, inferno. Hence summer. Sort of natural.

Unnatural: the bumps and lumps. Again, I repeat, hundreds. Maybe even thousands, if you wanted to count those who lay and sat around farther away, in places I couldn’t possibly see, with or without obstacles.

A blunt thump startled me. The madman in the boat-sized running shoes had slammed his palm against the dome. I took a step back. Flight, then? Even though he couldn’t attack?

But I didn’t back away another step. The madman wasn’t looking at me. He was looking at my copper watering can. And what glimmered in his eyes wasn’t fury and hatred. It was pure thirst—without accusation, without a sense of the future or the past, without a definition of him, me, and other individuals.

Just thirst.

I turned away. I could hear his palms making squishy sounds against the glass as they helplessly glided down. Good. There was still some moisture left in his tissues. He wasn’t going to die anytime soon.

2

Timothy didn’t look up from his screens when I entered the home dome and slipped out of my flip-flops. On the contrary: as expected, he focused more on his work as soon as I came in. He was grim, serious, and for some reason, tense, as if he weren’t the God of the domes, as if he was going to be late for an appointment.

His fingers danced over the keyboard. Tippaty tip. Busy, always busy, moving this and that part that required moving within his splendid paradise. The noise didn’t sound nearly as desperate and loud as the madman’s knocking, but his actions were much more effective. Incomparably so. When someone’s effectiveness was zero and another’s was a hundred, the latter wasn’t a hundred times more effective than the former. The latter was infinitely more effective. That shocking detail, I remembered from the little high school math I had taken.

He always sat in the dark. It was possible to open any plate that formed the black home dome, but he never did. The screen glow lit his bearded face and white T-shirt with a cool bluish tint. This should’ve been a relief after witnessing the blazing pale-brown heat; it wasn’t. But a little bit of solace did emanate from his eyes. They sparkled with intense purpose, the way they always had, probably for decades before Eternal Summer. Since birth, quite possibly. And they would keep on sparkling for decades more. Unlike the madpeople beyond the outer dome, Timothy was going to live out his natural lifespan, whatever that may be.

Perhaps he had a family history of cancer. He had never told me (he never told me much, just as I never told him much). But cancer usually didn’t kill people so soon—people our age; my age and the madman’s age; people in their early thirties. Of course, there were more random, quick causes of death, like a heart attack. If that was written in Timothy’s genes, he could keel over tomorrow.

That thought terrified me, of him dying tomorrow. It wasn’t because I particularly cared for him. Just the idea that I was unprepared scared me to death. I would be all alone. I didn’t know how any of the machinery here functioned. If I had known how to design and build such things, I wouldn’t have been the roommate/sex partner of the paranoid engineer. I would’ve built a dome of my own, probably smaller, less conspicuous. The massive air conditioners, the screens that were connected to the cameras adorning the near-top of the outer dome, all such technology were an enigma to me. I couldn’t have him die.

As if he had waited for me to realize that deepest desire inside me, he finally looked up.

“Interesting how those little things manage to survive in the direst of situations, isn’t it?”

“I guess.”

I knew he was talking about the flower. He knew I went to water it right around this time of the day.

“I think it’s beautiful, what you’re doing,” he said.

I froze. He was gazing directly at me. He rarely did that. The last time he had done that had been the day the dome was raised.

“Watering the flower?” I asked.

He nodded. “Saving one random thing that comes your way, even when you’re terrified.”

“I’m not terrified!” Sudden defensive anger swelled in my chest. He had too easily noticed a secret that I had only recently admitted to myself.

He shook his head minutely, more to himself than to me. His way of saying, Never mind, let’s change the subject.

“I made coffee,” he said. “It’s in the kitchen.”

“Thanks,” I snapped.

“Can you bring me another cup while you get yours?”

“Fine.”

I approached the desk to get his empty cup. His shampoo: minty, oceany, lemony, but surprisingly ineffective as a source of relief, just like the cool blue tint of the screens. He handed me his cup, the stain of his lips at a precise ninety-degree angle from the handle. Holding it at a safe distance away from my core (what did I think, that the cup was going to explode on me? ridiculous), I headed to the kitchen.

Here, a curved plate of the black dome, which I had opened up this morning, still remained open. A rectangular beam of sunshine flooded the space. The smell of freshly brewed coffee awakened me from the oppressive guilt that had numbed me since the encounter with the madpeople. Timothy had thought ahead of everything, not just the domes. Coffee in every shape and form was one of those things: pre-ground as well as beans and those little pods you inserted in the specially-manufactured brewing machines. Also, food: dry goods as well as a hydroponic garden. And sort of grossly, but when you thought about it, very considerately and smartly, tampons and pads and menstrual cups.

You have your pick, he told me, that day when he had raised the dome. Gazing directly at me, he sounded as earnest and openly despondent as a nervous travel agency clerk who’d been hired on the condition that he got the first customer who happened to waltz into the store to sign up for a space cruise.

Of course, Timothy was more prepared than such a hypothetical clerk could ever hope to be. He’d had time. Eternal Summer hadn’t shown up abruptly, oh no. Think of the world as a failing immune system. The process happens gradually. At some points during that process, as you continue to stuff your body with junk food, you may even deny its occurrence. But then whoop! and it’s too late to fix anything. When you got days after days of forty-something-degrees temperatures (Celsius, folks—Timothy abhorred Fahrenheit) pretty much everywhere in the world, you knew something was wrong. You didn’t need to be a mad engineer who built a dome in the middle of the desert.

Why did you build a dome here if you knew it was going to be Eternal Summer, not Eternal Winter? I asked.

Because of the extreme temperature variation, he said. These days, this desert is always hot, but it wasn’t always so. The summers were hot but the winters were freezing. The days were hot but the nights were freezing. I wanted to test and build at a location with such extreme conditions to ensure that what I had was safe. Also, there was just more space in the middle of this particular desert. Cheap space.

So even if Eternal Winter were to come, you’d survive inside the dome?

Yes. And you too, if you decide to stay. Soon, everything will melt. Everything will evaporate. Everything will die.

But why me?

What do you mean?

I mean, aren’t there other people who’d want this spot?

I don’t know. I haven’t asked.

I’m the only one you asked?

Yes.

That’s crazy.

Why?

Because… I mean…

I was truly embarrassed to ask, but I had to ask now, otherwise I would wonder forever:

What, are you in love with me or something? Love at first sight?

Mercifully, he took three seconds to absorb that question and then answered politely:

No.

So what is it, then? I’m just the grocery deliverer from the local supermarket. You’ve met me like three times for less than a minute each time. And you’re offering me a haven for life?

Why not you?

Huh?

You talk as if being the grocery deliverer from the local supermarket should disqualify you from being one of the two people who survives Eternal Summer with any certainty.

I didn’t say anything to that. He was right and he wasn’t being sarcastic. His beard slightly trembled with tense honesty. He expected me to refute again. I didn’t. That seemed to give him courage.

This won’t end, Nora.

You know my name.

Your name tag says your name.

I imagined a future in which this man of average height, average weight, and average handsomeness but sparkly eyes would be the only one to call my name ever again. Was he messing with me because he thought I wasn’t educated enough? I didn’t think this way simply because I was a grocery deliverer. Plenty of grocery deliverers were more educated than me. But no one, grocery deliverer or Nobel laureate, was more educated than him. And by education, I didn’t mean some college degree where you got a piece of paper that said you’ve paid for a diploma. This guy Timothy had educated himself. I mean, sure, he went to school and all that, but his genius hadn’t been taught by a few random professors. Timothy was a fanatic. Only a fanatic with a deep obsession could build a dome in the middle of the desert.

Okay, I said.

If he did something to me, I was going to kill him. There hadn’t been a need to do that, though. The only time he had unexpectedly grabbed me was on that same first day in the dome. And it wasn’t even anywhere embarrassing. He had grabbed my hand so he could get my fingerprints. For security, he had explained, as if he expected someone to break through his fortified glass. As soon as he noticed my discomfort at being thusly grabbed, he had whispered a genuine apology, genuine because of the embarrassed blush and all, and had never done something remotely similar ever again.

Really, I couldn’t hate Timothy. As I took out my own cup from the cupboard, I admired the kitchen’s sparkling clean counter. The cleaningbots he had built were about the size and shape of my forearm. Tirelessly, they did most of the repetitive cleaning of the surfaces.

We—the humans, Timothy and I—did the dishes. We took turns. Same with cooking. We took turns. We had sex because there was no one else and sometimes, we were both horny. Timothy wasn’t bad. My guess was that he thought the same thing about me. Nora wasn’t bad. We didn’t love each other, but what an extreme luxury was this, to be able to say It ain’t bad?

The guy was so polite he didn’t even walk around the home dome nude. He always wore a T-shirt and pajamas. (He had a few sets he wore at night and a few different sets he wore during the day.) But he did like walking around barefoot at home. No need for extra air conditioning, was his logic. That was why I took off my flip-flops when inside. And air conditioning aside, keeping outside things outside had never made more sense in the history of humanity.

Another thing to like about Timothy: he had prepared condoms. Lots of condoms. It was one of the things I most admired about Timothy, actually. He had the decency to be careful about creating unplanned offspring in this hellish inferno. Say if we had a child. What was that child supposed to do with themselves? Were they to live forever alone, as an involuntary celibate? What if we had several children and they lived together and… didn’t live as celibates?

So, all in all, Timothy was decent.

Could I blame him for not giving water to those madpeople? No. There was no water and no space, not for the hundreds, thousands outside.

I only wished Timothy would tell me more. Not the technical details, necessarily, but why he did things. If we’d had such conversations before, I wouldn’t have snapped at him when he had mentioned the idea that I was terrified. I might have told him that the primary driving force that I had learned to accept was guilt. And I had the sense that he might be driven by the same feeling. If not, why did he watch the screens most of the day? Why did he start typing so madly when I returned after watering?

In our respective cups, I poured coffee. The air here was warm, but the steam hotter. It whirled freely over the cups for a few seconds, then dispersed. But that spread of heat didn’t alarm me. We had the air conditioners. Thanks to Timothy.

Cancer wouldn’t take him anytime soon. A heart attack, especially not. Why would it? When he wasn’t monitoring the screens, Timothy worked out religiously. Two hours per day, every day. Even when the outside got so unbearably hot that our air conditioners seemed to slack, he exercised. Not for prettiness either. None of the “toned” and “sculpted” muscles and some such bullshit. He trained his muscles for practical purposes: to lift the heaviest weight, to run the longest miles.

This can be justified—heat generation during exercise, he always said. It’s the most cost-effective way of ensuring one’s well-being.

And no wonder he cared about his well-being so much. Sometimes, even his sharpest of tense states appeared inexplicably depressed. For some reason I thought those two didn’t belong together: tension and depression. But there he was, lifting or running, his eyes emanating that intense purpose that comforted me…

…when I knew full well that his razor blades were dull, always the most curiously ineffective elements about him, his beard never long but never trim either—as if he didn’t dare put a sharp blade near his throat.

He wasn’t a bad person. Which was why I didn’t mind, no, liked bringing him his coffee. It was the least I could do for him, my savior, who didn’t force me to clean and cook, didn’t turn me into a sex slave, didn’t threaten to kick me out.

I held the cups by their bottoms because that felt more secure than holding them by the handle. The warmth of the coffee transferred to my palms. It was a luxury I could afford. And it felt good.

Timothy slept in front of the screens. That was a first.

“Here’s your coffee,” extra kindly, hoping he didn’t feel hurt after the way I had snapped at him.

I put his cup next to him. He didn’t wake up. He lay over the keyboard.

“Timothy?”

He didn’t respond. Instinctively, the first thing I did was to place my own cup next to his. Dropping the cup and spilling hot coffee all over the place was something I most definitely did not want at the moment.

“Timothy.”

I poked his shoulder. He didn’t budge.

I poked harder. He didn’t resist. I kept pushing…

The black mesh swivel chair rolled back. Limply, Timothy collapsed on the floor. He didn’t wince or moan.

Heart attack. Brilliant.

3

The tears came a while later, after I put Timothy’s body in the incinerator. He burned everything in the incinerator: paperwork, food waste, other waste. And now, I was going to burn him.

Sometimes, he had spent hours in the incinerating room, doing God knows what, probably chopping up the waste into smaller bits so it would burn off with less energy. I appreciated him doing it without asking me to take turns. Mostly I cooperated by eating everything on my plate.

Incineration was the only way to avoid culturing harmful bacteria within the domes. Also, imagine the reek, if we had kept everything inside. Bad. That was why I didn’t wait for a day or three days or however long it took for a person to ascertain that another person was really dead. That, and how spooky it would be if I had to live with a corpse for that long.

I waited for exactly three hours, leaving him collapsed by the swivel chair, because to drag him up and take him elsewhere would only verify his death sooner.

Timothy didn’t budge. He had to go. I knew it, so I did it. Nora Haynes. The woman who did what she had to do. Super.

In the first few moments of putting him in the incinerator, the situation felt so surreal and distant, I morbidly wondered about the sound of burning bones. Did it sound any different from paper burning? Probably. Absolutely.

I examined the buttons. There weren’t many. One said “Empty.” The other said “Begin.” Surprisingly simple.

“Empty” sounded too ominous, as if the machine were asking me if I wanted to rid Timothy from this world, completely. (Which, I guess, was exactly what I wanted to do, but hey.)

“Begin” sounded more hopeful. So I pressed that.

The door locked from the inside with a click. But no other sound came. Timothy’s incinerator had thick walls, just like the outer dome and home dome. What happened inside stayed inside. No need to be tortured by the happenings from the other side, unless you had a masochistic tendency, like me when I went to water the little yellow flower and give the madpeople a chance to hate me.

I couldn’t even see his flesh burn, because there was no window on the silver front. And because the incinerator performed its job as perfectly as all the other inventions that Timothy had left behind, I felt no extra heat while staying in that barren white room. Still in my tank top and shorts, I cried and cried. My tears were probably the hottest substance affecting the temperature inside the domes. They trickled into my mouth. Salty. Gotta drink water. Dehydration was the most dangerously lethal thing I could do to myself right now.