Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

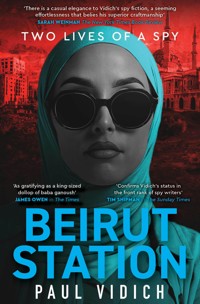

'Vidich has firmly established himself in the very top flight of espionage writers, with a series of slow-burn character studies putting him in the line of le Carré.' - CrimeReads A stunning new espionage novel by a master of the genre, Beirut Station follows a young female CIA officer whose mission to assassinate a high-level Hezbollah terrorist reveals a dark truth that puts her life at risk. Lebanon, 2006. The Israel–Hezbollah war is tearing Beirut apart and the country is on the brink of chaos. The CIA and Mossad are targeting a reclusive Hezbollah terrorist. They turn to young Lebanese-American CIA agent, Analise, who has the perfect plan. However, Analise begins to suspect that Mossad has a motive of its own. She alerts the agency but their response is for her to drop it. Analise is now the target and there is no one she can trust. A tightly-wound international thriller, Beirut Station is Paul Vidich's best novel to date.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 384

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Paul Vidich

‘There is casual elegance to Vidich’s spy fiction (now numbering five books), a seeming effortlessness that belies his superior craftsmanship. Every plot point, character motivation and turn of phrase veers towards the understated, but they are never underwritten’ Sarah Weinman, New York Times Editor’s Choice Selection

‘Vidich adds a welcome feminist twist to the familiar espionage theme of human lives trapped in the vice of competing and equally ruthless governments. From An Honorable Man (2016) through The Mercenary (2021), Vidich has established his position in the forefront of contemporary espionage novelists’ Booklist

‘[The Matchmaker] With a great narrative and powerful plot twists, the story comes to life and all is slowly revealed by the final chapter. This surely lives up to the standards of Graham Greene and John le Carré, as denoted in the dust jacket blurb. Kudos, Mr. Vidich, for an entertaining read that left me reminiscing of the days of the Cold War’ Mystery and Suspense Magazine

‘[Beirut Station] A cool, knowing, and quietly devastating thriller that vaults Paul Vidich into the ranks of such thinking-men’s spy novelists as Joseph Kanon and Alan Furst’ Stephen Schiff, executive producer of The Americans

‘Vidich writes with an economy of style that acclaimed espionage novelists might do well to emulate’ Booklist(starred)

For Linda

‘The spirit lives within me,

our savage ancient spirit of revenge.’

– Agamemnon, Aeschylus

Robert Fagles, translator

PART I

1

Beirut

July 2006

Beirut’s heat wave made the evening air in Analise’s apartment oppressively warm, and she was glad her hardship tour was ending. The last bit of agency work, and the most dangerous part, was coming in the morning. She rehearsed what she had to do, going over the details – the vehicle, the bomb, and the face of the targeted man. She closed her eyes to summon a memory of his photograph, but a whispered question interrupted her thoughts and her mind returned to the man lying next to her in bed. He had said, ‘What’s troubling you?’ and was waiting for her answer. When she could no longer stand the silence, she crossed the bedroom and threw open the window for the weak Mediterranean breeze. Nearby pop music and laughing voices came in with the cooling air and relieved her sense of confinement. She smelled the tobacco of his cigarette and felt the sea air on her skin.

‘It’s nothing to do with you,’ she said, returning to bed. She knew the mistake that men made, thinking that silence after coitus was a woman’s way of expressing dissatisfaction. She stretched her hand up toward the ceiling fan, her wrist moving one way, then the other, watching how light from the half-closed blinds carved ribbons on her small hamsa tattoo. She clenched and unclenched her fist, letting the dim illumination deepen the red markings.

‘Why did you have it done?’

‘This?’ She lowered her hand. ‘It brings good luck and wards off evil, if you believe in that sort of thing.’

‘How long does the henna last?’

‘Three weeks. Maybe a month. Then it fades. Like everything.’

‘Something is bothering you. You’re not the type to depend on luck.’

She turned on her side and looked into Corbin’s eyes – wide, mysterious, and content. She felt no obligation to respond to his comment, which she knew was something he’d said to fill the silence. The tattoo was there to be done, and she had done it on a whim, feeling vulnerable, wanting to avail herself of whatever powers it offered. Little of her life was spontaneous then, and she had done it because she could. She wasn’t going to tell him that, or anything else, and certainly not what troubled her. She had trained for what was coming the next day and prepared her mind to be ready if everything suddenly changed, her life at risk. Her non-official cover with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees wouldn’t protect her from an angry mob.

Their eyes lingered on each other – hers dark and almond-shaped, his green and round but darker in the dim light. Her long, olive-complected legs were next to his pale white form, and for all their intimacy she felt the distance of their different backgrounds. She took his cigarette and put it to her lips, brightening the end, and exhaled from the corner of her mouth. She handed it back.

‘You said you quit.’

She thought of the ironic comment she could make, but it was not the time or place to hurt him or be insincere. ‘You need to leave soon.’

Car honking and the whine of a motorbike came through the window. Lebanese voices argued in the street, a woman’s rising in shrill protest.

‘What’s she saying?’

‘She is pleading with her husband to leave the city. She says that it isn’t safe now and they will be stuck when the war reaches Beirut.’ Analise saw that his interest had drifted to her knobby knees.

‘What’s your view?’ she asked.

‘It’s late. I don’t have a view.’

‘It’s not like you to pass up an opportunity to give your opinion. Your sources are big shots in Tel Aviv. All I have are the wild rumors from refugees who show up at the UN fleeing the fighting.’ She respected his work, which made it easier to put up with his behavior. She had consented to sleep with him that night because he had shown up at her door with alcohol on his breath. They were two people in a war zone who had fallen into a pattern of casual sex.

He raised the cigarette above his head, watching the ember burn, and in doing so revealed the small serpent tattoo on his wrist.

‘When did you get it?’

‘This?’ He flexed his wrist so the serpent moved. ‘I had it done after I discovered my wife was cheating on me.’

Her eyes narrowed. ‘That explains why you’ve picked up tourists in bars and fucked prostitutes. A frenzy of promiscuity to lighten the burden of your betrayal.’

She rounded the word’s vowels to soften her sarcasm and looked at him tolerantly. She saw his eyes move across her body, and she knew that he was mildly smitten with her. There was a pause between them as she accepted his interest, her eyes trying to look into his mind. She indulged his talent for casual womanizing, and against her better judgment she found him oddly sympathetic. She allowed his fingers to travel along her thigh.

‘What’s so important that you have to get up early?’ he asked.

‘Work.’

‘The job you say you’re quitting?’

‘Refugees don’t suffer nine to five.’

He smiled and his hand moved to her knee. ‘There will be more.’

‘I won’t be the one to process their papers. It’s hard to look into their eyes and see desperation. It’s easy for you. You sit at your laptop, listen to the other reporters, file stories, and then drink at the bar. Or come here.’

She removed his hand. ‘It’s late.’ Her brisk tone was meant to shut down his flirting. Suddenly, she rose from the bed and moved to the sliding door where a large X of masking tape protected the glass. She looked south but saw only Beirut’s hills and rivers of headlights on nearby streets.

‘What is it?’

She pointed.

He was at her side, Blackberry in hand, looking into the night. Darkness provided a curtain of modesty from the many people who had moved to their balconies, drawn by the distant sound of a jet aircraft. Everyone’s attention went to the canopy of night, looking for Israeli warplanes, but clouds obscured the sky.

‘Where will they strike?’ she asked.

‘It’s probably a false alarm.’

‘Do you believe that? The IDF crossed the border with tanks. Don’t you read your own stories, or do you just hand them in? Words on the page?’

She watched him dial a number on his phone. Her eyes moved back to the view south. A brilliant flash lit the sky, and it was followed by a massive fireball that rose into the night, billowing smoke. Startled cries in the street mixed with murmuring voices, and an eerie quiet followed.

Analise counted the seconds until the sound of the concussive blast arrived. ‘It’s the airport or Hezbollah headquarters in Bourj al-Barajneh.’

Another bomb hit in the distance and lights in tall apartment buildings flickered before electricity was lost. Sirens wailed, and then the gravity of the bombing sank in, the quiet summer evening becoming a chaos of calm unease. A hurrying couple with a baby stroller sought shelter in a building lobby, an elderly man with a cane looked up at the sky, and everywhere barking dogs. Anti-aircraft bursts cast little yellow smudges on the dark canvas of night.

‘It’s me, Corbin,’ he said, when his call went through. She was beside him, but he was indifferent to her presence. ‘Israel is bombing the southern suburbs.’

His head was turned away and he had lowered his voice, but she overheard fragments of the conversation. She was careful not to show interest, but took note of what he said. She met his eyes when the call ended.

‘They want a story for New York’s morning edition. I have to go back to my hotel.’

‘Take a shower while there’s still hot water.’

‘I don’t have time.’

He grabbed his pants from the floor, where they lay in a heap, and shoved one leg in the trousers and then the other, cinching the belt over his abdomen. She had found his body attractive the first time she saw it, and that was one reason she continued to see him despite being warned to call it off. She gave him what he came for, and she took whatever information she could winkle from him.

When they stood at the apartment’s door, she fussed with his collar, straightening it, and kissed him briskly. A shadow crossed her face. ‘There may be roadblocks. Be careful.’

At the balcony, she stood wrapped in a sheet, arms across her chest, and watched him flag a taxi. He waved at her and called out something she couldn’t hear. This has to end, she thought.

She gazed at gray smoke pluming into the starless night. The air was warm but she felt cold. It was always that way the night before an operation, particularly one in which a man’s life would be taken. She was glad to be at the end of her tour and glad to be moving on. There was a plan in place, and what mattered was that the plan kept her from thinking too much about her role. She merely had to maintain cover and do her part. Most intelligence officers needed to be trained to compartmentalize their lives, but Analise’s instincts had sprung from her chrysalis fully formed. She never hesitated to close down a concern, and she could give a dozen explanations for what she was doing, or where or why, each more convincing than the truth.

2

Somewhere in Haret Hreik

Analise was there at the agreed-upon time and place, but the Mossad agent hadn’t shown himself. She paused to study one man’s reflection in the clothing store’s display window, half-shuttered to protect against the bombing. A scarf covered her head and her focus on the mannequin in the window disguised her interest. Oversized Prada sunglasses hid her concentration as she followed his movement across the street.

She had noticed him after passing Al Qaem Mosque, and he was there each time she moved up the street and stopped at another closed shop. He was behind her in a long queue of men that snaked toward a Coral gas station selling liters of rationed gasoline in plastic jugs. His face was hidden by a keffiyeh, and he wore a Western-style sport jacket and tan cargo pants. Bauman? she wondered. Her Mossad counterpart hanging back? Or Hezbollah surveillance?

She glanced around for more surveillance – the appearance of one man augured the presence of others. She adjusted the wireless earpiece hidden under her headscarf and tapped the mic, speaking softly. ‘I don’t see him.’

She walked toward the man, looking past him, but her peripheral vision noticed his shoes, the ring on his finger, the make of his wristwatch – seeking one confirming detail. She had moved past him when she stopped and searched her string bag, mumbling in Arabic, ‘Damn it. I forgot the bread.’ From the corner of her eye, she saw that he had stepped out of the queue and followed her.

Crackling in her earpiece carried a broken conversation and then a command. ‘What do you see?’

Dust billowed where workmen clawed at the rubble of an apartment building destroyed by the Israeli air strike. Laborers’ cries mixed with the whine of passing motor scooters, and anxious mothers with tissues over their noses shooed children away from the tangle of fallen electrical wires. Western journalists, some wearing gauze masks against the stench of death, watched as workmen dug for bodies, wary of unexploded ordnance. At the far end of the street, girls lined up at a crude pipe, filling water bottles from a broken spigot.

Analise whispered every detail, knowing that she was the eyes and ears of the men in a panel van parked a kilometer away.

‘Surveillance?’

‘One maybe. I can’t be certain.’

‘Guards?’

She looked at a three-story house guarded by two young bearded men with AK-47s. They stood by a parked Jeep Cherokee and scanned the street with the diligent scrutiny of sentries. ‘Two.’ Then curtly, ‘Where’s Bauman?’

‘No names!’

She cursed the rebuke. How had she gone from blessed monotony in the final week of her tour to this adrenaline punch? All she wanted to do was close her eyes and open them when it was over. It was happening again, the doubt, the fear, the feeling that she had forgotten her training, and the irresistible impulse to flee. Breathe, she told herself.

Her eyes darted across faces in the street.

‘He’s there. Sport coat and trousers. Behind you.’

She glanced up at the drone, realizing she was being watched from the van, and then turned. She raised her eyes, looking past the tall man in the keffiyeh and then right at Bauman. Their eyes met, a brief moment of recognition passed, and then the caution of two people falling into the practiced regimen of covert work.

Analise walked toward the Jeep, noting the license, glancing at the house’s wood door, but she kept moving close to the shops to avoid debris in the street. Her head was down, eyes looking past her footfalls, ears a tuning fork for danger. Beads of sweat on her forehead moistened the edges of her headscarf.

Intelligence was always exactly wrong, but if she was lucky the intelligence for that day would be generally correct. She and Bauman were ground spotters tasked with observing what was hidden from the overhead drone, and she instinctively slowed as she neared the Jeep. Time became elastic, stretching as she waited for the one detail she needed.

When the door opened, a burly man in a polo shirt with a pistol stuffed in his belt walked to the Jeep. His aviator sunglasses glinted in the sun, and he wore the smug attitude of a man of little stature entrusted with work of great importance. He pulled one driving glove tight onto his hand, then the other, and after nodding to the guards, he waved at the door.

Qassem stepped into the sunlight. Analise recognized him at once; he matched the photograph she’d committed to memory. She had been instructed to approach Qassem’s grandson and find a way to earn his trust, so she had become a volunteer teacher at his school. Once a friendly relationship had formed between student and teacher, she had gathered intelligence on the grandfather. The notoriously secretive Hezbollah militant was a man as much as he was a jihadist, and she looked for a way to exploit his humanity, knowing that every man had his weakness. Some men succumbed to greed, others power, a few to addiction or carnal urges. The trick was to find the right bait to compromise the man. Qassem was a tough case. He was surrounded by an insular group of clan members, and he moved frequently, which made it difficult for the dogged intelligence officer to track his whereabouts. But Analise used his affection for his grandchild to locate him.

Qassem lit a cigarette and drew deeply, smiling at his driver, exchanging a careless remark that Analise was too far away to hear. He was a heavyset man in his mid-fifties with short silver hair that matched a coarse graying beard, and he joked with his driver. A lighthearted moment of a confident man who was completely unaware that he was being watched.

‘Talk to us. What do you see?’

‘He’s outside,’ she whispered. Street sounds were all around, but she concentrated on the two men by the Jeep whose attention had turned to the group of Western journalists touring the night’s bomb damage. Qassem watched impassively with the confidence of a patient fighter comfortable in his neighborhood.

‘Two men.’

‘Who’s the other?’

‘His driver.’ Crackling on the line. ‘Can you hear me?’ She turned her head away from the house and spoke louder. ‘Target and driver.’

‘You’re sure?’

‘Yes.’

She recognized the Israeli accent and knew it must be Gal. He was the Mossad lead and mission architect. She’d confirmed Qassem’s location in the neighborhood the week before, and the bombing had trapped him until the operation could be assembled and the Pajero positioned. Weeks of careful planning and they were arriving at the moment when the best intelligence of the combined efforts of the world’s top spy agencies would be tested, their reputations put at risk.

Suddenly, Qassem’s two grandchildren – a skinny teenage boy and his sister in a hijab – emerged from the door and were hustled by the driver to the Jeep. He pulled the sullen girl by the arm, hurting her, and the boy protested loudly, but the driver responded indifferently. The mother was at her children’s side, consoling them, waving off the driver with a dismissive gesture, but then she calmly encouraged them to get in the Jeep, kissing them, giving each a warm pat.

Analise turned to keep the boy from recognizing her and veered toward an alley. As she moved, she encountered the press group standing before the crumpled apartment building. Journalists and photographers gathered around a slender man in a red military beret who gestured toward a limp hand protruding from the rubble. Cameras’ whirring clicks were a counterpoint to the man’s accented English, but over it she heard her name shouted.

‘Analise.’

Her head didn’t turn and she remained oblivious, as if the name belonged to someone else. Her name, again, louder and more strident. Corbin had pulled away from the Hezbollah press guide. His dark glasses were propped on his head; he lowered them and stared.

‘Analise!’

Without breaking her stride, or giving Corbin the satisfaction of a confirming glance, she slipped into the alley. Once around the corner, her pace quickened. She listened for running footsteps.

Jesus, fuck, she said to herself. Her training kicked in and she continued on with her string bag of vegetables like a woman returning from the market with the evening’s dinner. Fuck, fuck, fuck. The curses were a loud drum beat in her ear as an image of Corbin filled her mind’s eye. All the gnomic briefings, all the concentrated thinking about escape paths and contingencies didn’t account for the operation of chance. Her mind was numb to the random connections that had fallen into place to bring her and Corbin to the same patch of earth that afternoon. What were the odds?

She gripped her handbag and continued apace without hearing footsteps behind her. Corbin wasn’t following, and then he was gone from her thoughts. There was only pulsing in her ears and the soft padding of her shoes in the narrow alley. She brought the microphone to her lips and whispered to the men in the van.

‘Two kids,’ she said.

‘What?’

Louder. ‘Two kids in the vehicle. Abort.’

‘We lost you. Where are you?’

‘An alley. Coming to you.’

Analise emerged from the alley and walked past a ruined mansion, doubling back when she was certain it was safe and opening the door with a strong shoulder push. The shortcut avoided Corbin. She listened for the telltale sounds of danger and then she rose through the interior well’s staircase, open to the sky, taking steps two at a time, almost flying up like a bird, quiet and swift, until she came to a wood door that guarded the top-floor apartment. A bomb had punched a gaping hole in the roof, but the door into the apartment stood intact, still attached to the crumbling walls. She moved through the ruined living room to the fire escape, taking in the damage. She stepped around broken glass from a tall parlor window that had blown in. Wall plaster was cracked and streaked with water damage, and a child’s doll had been left behind in the rush to flee. An orange western sun flooded the once magnificent room with a warm glow that made the russet sofa burst with flames. Electricity was gone, but the sea breeze coming in the window turned the ceiling fan in squeaking rotations. A trespassing rodent scrambled out of sight.

She crossed adjoining roofs and entered another stairwell further on. A central atrium connected the buildings, and at the base there was a courtyard with shattered pieces of fallen cornice. She descended the stairwell two steps at a time, passing rooms now open to the sky. Unexploded cluster bomblets lay scattered on the landings, but over successive visits planning her route she had come to ignore the danger. Analise hurried down to the dark lobby where she saw a tall man silhouetted in the front door. At the sound of her footsteps, he turned.

‘What held you up?’ Bauman asked. He’d removed his kaffiyeh so his tanned face was clearly visible – a coarse-blond South African in baggy fatigues with his press credential in a plastic keeper now around his neck. His thin lips were pursed and he stood tall and brooding.

‘Corbin saw me. I had to come a different way.’

‘Did he recognize you?’

‘He called my name.’

A tremor of silence followed and the whole fraught history between them was punctuated by Bauman’s quick judgment. ‘That’s unfortunate.’

They heard the muezzin’s amplified call to prayer, which did little to empty the street. Then a shouted command came through their earpieces. Together they moved across the street toward a white Agence France-Presse panel van. She slipped in and Bauman followed, closing the door.

Rick Aldrich, Beirut’s station chief, was already there, as was Gal, his Israeli counterpart on the operation. Upon hearing the door close, they looked up from the monitor showing a drone image of the Jeep. Aldrich had the brisk irritation of a man whose concentration had been interrupted. Tall, in his early sixties, he had a rugged face paled by sleepless nights, and intense blue eyes. He had the impatient gruffness that came with dangerous covert work, but she knew that he thought of himself as a CIA officer who took the risks he assigned to others. He was a man of discretion and nerve who rarely raised his voice, but his fierce gaze could vanquish. He was part of the old guard new to the war on terror and he occasionally slipped into the heroic anachronisms of the Cold War, making him sound out of touch.

‘There are two kids in the Jeep,’ she said. ‘Abort!’

Gal was mildly annoyed by her tone. The Mossad agent was older, his body frail with age, but he was clear-eyed and had the quiet expression of a man who listened patiently but formed his own judgment. He had delicate hands with manicured nails. They were not hands that could strangle a man or point a gun. They were the hands of a bookkeeper who recorded debits and credits against his adversaries with tick marks in a ledger book. No one would look at him and think he would start a fight in a bar.

Gal turned back to the monitor, watching closely. The screen showed the Jeep avoiding a bomb crater, moving through the maze of narrow streets toward the parked Pajero. They all knew what was coming, and they understood that one step was taken and the next would fall soon. A powerful explosion would engulf the Pajero, sending shrapnel from the shaped explosive into the passing Jeep. Semtex was a precise explosive but its lethal blast killed indiscriminately, friend and foe, young and old, guilty and innocent.

‘Did you hear me? Two kids.’ She remained frozen before the three men, who looked at her with collective skepticism. Men at the moment of victory being asked to stand down. The taste of blood, and the satisfaction of revenge hot on their faces.

‘Fuck it,’ Gal said. He turned back to the screen and waved to the quiet technician who operated the monitoring equipment, taking the cell-phone detonator in his hand.

The drone’s camera closed in on the moving Jeep, enlarging the flat image to show the SUV from above. It enlarged again, moving closer in. A child’s hand was clearly visible hanging out the rear window, playing with the air.

The late-model Pajero had accumulated a fine layer of dust and looked like any other SUV popular among Hezbollah militia. The license plate was dirty and the cover of the spare tire attached to the rear was shredded in one spot. Great effort over several weeks had gone into making the new vehicle look old and weathered from long use on Lebanon’s harsh roads. Nothing had been overlooked. A particular yellow dirt from the Beqaa Valley had been flown to North Carolina and embedded in the wheels and chassis to imitate the appearance of wear. Only the VIN had been removed to prevent determined investigators from tracing the vehicle’s origin.

Images from a second drone appeared on another screen, and the monitors vied for the attention of the five people in the van. The overhead shot alternated with a low-angle front view from a drone hovering in place somewhere along the street.

‘Bag him,’ Bauman said, his South African accent at its gentlest and most appealing.

Analise looked from Aldrich to Gal and then glared at Bauman. ‘We had an agreement.’ A human silence lingered amidst the electronic hum of monitors and communication devices controlling the drones. Analise put on the face of superhuman tolerance. ‘What are we doing?’

‘It’s going down.’

‘I was seen. He’ll make the connection.’

‘It doesn’t matter. Your part is done.’

‘There are two children in the Jeep.’

She felt the insult of their patronizing indifference, and all the old anger at her treatment in the agency welled up. Catcalls in training, male camaraderie that excluded her, and crude sexual advances. The whole weight of her struggle to be respected. They were the senior male officers who would get the glory and she was the junior female colleague who would suffer the sting of knowing she had ginned up the boy with appalling lies to earn his trust. This isn’t happening, she thought. Her parting gift from the agency would be a lifetime of resentment.

‘This whole bloody thing is what exactly?’ She looked around. ‘So exactly what are we doing here?’ She had grabbed Gal’s neatly pressed sport jacket and swung him around. They were the same height, but he was older and weakened by asthma. Everyone’s attention moved from the monitor to her violent confrontation.

‘And you?’ she asked Aldrich.

‘Two blocks away,’ the quiet technician announced, an imperturbable cog in the operation, and everyone’s gaze was briefly drawn back to the monitor, where the drone’s camera showed the Jeep moving up a deserted street, then taking the required detour created by a bomb crater and moving toward the Pajero parked further on.

Faint staticky voices from the second drone and then dead silence until an American’s voice somewhere off camera in Haret Hreik came on, shrill and petulant.

‘Kids in the vehicle. Do you hear?’

Gal spoke patiently. ‘He is a wanted terrorist, a high-value target with blood on his hands, and this mission has been planned for months. For me, it’s been years.’

‘This isn’t right,’ she said.

Gal’s eyes narrowed. He said nothing. No anger. No remorse. No defense against the indefensible. The technician’s countdown of the Jeep’s rapid approach to the Pajero created an urgency in the cramped space.

‘You made the bomb,’ Gal said, wheezing. ‘We take responsibility. Your hands are clean. You’ve made your concern known and I’ll be certain to note your objection in my report.’ He turned to the monitor.

‘They’re kids.’

‘There are no innocents,’ he said. ‘Only casualties.’ He nodded at the technician who held the cell-phone trigger.

Analise turned to Bauman, appalled by his silence. She saw the impassive face of a man condemned to heartless extra-judicial murder. He was reluctant, but not so reluctant that he spoke up. She had begun to wonder about his indifference. The cold vacant expression on his face was something that she wouldn’t forget.

Aldrich’s jaw clenched and his eyes narrowed – an angry bull. He was at the technician’s side in one long stride and his entire body vibrated with indignation. He took the cell phone and shut it down.

‘Kindly note that I am the senior field officer in this situation. A final decision to proceed is mine, as you are aware. You may recommend; however, I decide.’

‘That’s not how we cooperate,’ Gal said.

Aldrich’s arm rose in a long arc across the top of the van toward the scream of low-flying Israeli jets. ‘Next time, have the courtesy to warn me you’re starting a war so I don’t have to look like a goddamned idiot when Langley asks what’s going on.’

‘The White House knew. It’s their job to share the information, not mine.’

Everyone was aware that during the argument the Jeep had passed the Pajero and was now beyond danger, traveling through the maze of streets. No one needed to say the obvious. The mission was over. Ended. All that remained was the filing of competing after-action reports that put an anodyne gloss on a catastrophe.

Gal took his eyes off the image of the Jeep on the monitor, now escaping its fate. He breathed lightly and shrugged. Disappointment and acceptance: the twinned emotions of a patient hunter.

‘So that’s it. We plan again, but let’s not kid ourselves that it will be easy. They have learned how to play the game. Hezbollah has created its own protective covering, moving between houses, changing cars and escape routes, shutting off cell phones that we can intercept. Never patronizing the same restaurant. We won’t get another easy chance.’

Gal put a comforting hand on Bauman, accepting the unwelcome disappointment. ‘We are all human beings. I have children, they have children, we all have grandchildren, and we all want a simple life to live in peace with other families. It is true for us and for most of them, but there are among them loud voices who want blood for blood and will never let peace live. Qassem is one such voice. So he can’t be allowed to live.’

Gal looked from Analise to Aldrich and then at Bauman, who hardly contained his anger. ‘We will try again. A new plan.’ He looked at Analise. ‘Suggest something.’

He nodded at the van’s driver, who had turned his head and looked through the small window into the rear of the van. The signal to leave. Gal sat on the bench against one wall. All eyes were on him. The storied Mossad agent had joined Israel’s National Intelligence Service in the sixties and had risen in its ranks. Each person in the van knew he had made a career of hunting Qassem.

‘Am I disappointed? Of course.’ He added, ‘I have been disappointed before and I’ll be disappointed again. I see a question in your faces. What’s next? It is not a question I am prepared to answer. It’s the same question since the destruction of the second temple. The gift of prophecy is given to the fool.’

Failure behind them, a new exhaustion settled on the five people as they sat in silence, bumping along the unpaved street, a bitter loss after a well-played match.

‘What do I tell the Knesset?’ Gal asked. ‘To save two children we let our number one terrorist go? And then tomorrow he kills again?’

‘You have it backwards,’ Aldrich said. ‘Better one hundred guilty go free than one innocent life is lost.’

Gal grunted. His hand made a weak, dismissive wave. ‘You are in the wrong job if that’s what you believe.’

3

Rue Gouraud

Analise’s surveillance detection route had begun two hours earlier, and she was confident she was clean, having passed Mohammad Al-Amin mosque’s blue domes twice, circling back to confirm no one followed. Her scarf wrapped her head and oversized Prada sunglasses hid her face from casual passersby. She removed her cell-phone battery before entering Achrafieh’s glass-domed shopping mall.

The old souk of her grandmother’s memory, with its narrow streets of covered awnings and displays of fragrant flowers and ripe fruit, was destroyed in the civil war; the new mall was soulless with brand-name retail shops. She stepped off the escalator and moved patiently from one store to the next, an elegant shopper looking for a bargain. In one, she fingered a Ferragamo scarf and smiled at the price, high even by the new standards during the war. She haggled, enjoying the shopkeeper’s game, and played along until she heard a loud cry from a group gathered around a large-screen television. News coverage of ambulances racing to hospitals was interspersed with graphic images of buildings collapsed by Israeli bombs, and suddenly the shopkeeper cursed the West, staring suspiciously at Analise. Part of her hated the stress of the work, constantly alert to being recognized or followed, and always needing to repel suspicion. Another part of her was exhilarated by the danger and enjoyed retreating into the mind of a calculating intelligence officer. Two lives, one open and known, a lady working for the United Nations, the other an agent known only to Mossad and the CIA’s station chief.

*

Analise paused at a narrow alley just off Rue Gouraud, where a music store projected loud hip-hop onto the sidewalk, nearly empty from the war. Once more she dawdled; once more she took stock of the people nearby, looking for surveillance.

She joined several passing stylish Lebanese women, acting like one of them, but she cleaved off when they passed an alley where the second-floor balcony of a pink Ottoman-era home was graced with a trio of arched windows. Houses didn’t have identifying numbers, but Aldrich had described the recessed front door. Analise ducked under the lush jasmine that cascaded from the balcony and approached the door, knocking three times, as instructed.

The woman standing before her was tall and attractive, dressed in a long skirt and silk blouse that left her arms uncovered. Two shrewd eyes appraised Analise’s dusty boots and tan trousers, and the woman briskly offered a hand. ‘Marhaba.’ Analise found herself in a lofty central hall filled with dim sunlight that seeped through mashrabiya latticework. The air in the dark hallway was as cool as a vault. She fell in behind Aldrich’s friend, climbing the wide stone stairs, and wondered what type of Lebanese woman would accept this type of arrangement. Aldrich’s first marriage had been to a glamorous, intelligent American journalist who chafed under the demands of his long hours and secret work. She left him during an overseas posting for one of her several lovers, and Aldrich, no longer a young man with the stamina for adventurous romance, had found it convenient to take up with a Lebanese woman who was unlikely to betray him in bed.

Analise entered the second-floor parlor, where Aldrich was across the room drinking a martini from a stemmed glass. His graying hair was casually swept back on his forehead, and his rumpled linen suit loosely fit on his trim form. He turned to her with the trained calm of a cautious spy, but confirming it was her, he smiled courteously and invited her in.

‘Vodka martini straight up? Two olives?’

‘No thanks.’

Aldrich turned to the woman at the door. ‘Shukran. That will be all.’ She retreated to the hall, closing the door.

He looked at Analise. ‘There is a risk meeting like this, but what I need to say has to be said in person. Hama is discreet, but I don’t take unnecessary risks. I told her you volunteer at the International College middle school, so if she asks around, she’ll get the same story.’

Aldrich moved to the arched balcony doors, motioning for Analise to join him, and pointed at two white sport utility vehicles parked at the end of the alley. A tall American woman in tan fatigues stood alertly by the lead vehicle, scanning vigilantly for threats. She dressed the part of a security detail – dark glasses, side arm, and a grim face, listening to chatter on her wireless earbud.

‘You know Helen?’

‘We trained together. She’s helping get the boy’s sister out of the country.’

‘I stopped holding meetings in Beirut Station’s secure conference room in Awkar. My sensitive conversations found their way to Langley and then to Gal. The Awkar compound has watchtowers and concertina razor wire, but there are people on the inside who I worry about. When I want a private conversation, I have it here.’

Aldrich nodded at the SUV. ‘I told Helen that I couldn’t do my job from Awkar. My assets wouldn’t risk being seen walking past the marine guards. When I moved here, she insisted that I have a double.’ Aldrich nodded at a tall man who stepped out of the decoy SUV – Aldrich’s height, similar graying hair, and an identical rumpled linen suit. ‘He has a vague idea who he is impersonating and how dangerous it is, but he is well paid and probably sees it as a good alternative to retirement in the States.’

Aldrich directed Analise’s attention further along the street to an Arab-looking man on his cell phone. ‘Mossad. They follow us too. We need to work together, but he’ll play us if it’s in his interest. Gal kept us in the dark on the invasion.’

He looked toward a narrow slice of harbor view where a glistening white cruise ship and gray navy cruisers were assembled to evacuate foreigners stranded by the war. Acrid gray smoke from bombed fuel tanks at the airport rose in the distance and darkened the sky. Aldrich’s entire body vibrated with irritation. ‘They played Washington. The White House was alerted, but they didn’t know it would be like this. Bombed bridges, roads, and villages. Airport runways cratered. An exodus of desperate refugees that has overwhelmed Beirut.’

Aldrich turned to her. ‘And for what? Two kidnapped Israeli soldiers?’ He looked at her. ‘Gal’s response, “the White House knew.” Arrogant crap. We’ll work together because we have to, but I have no illusions about them. This war is a mistake. It complicates our job.’

Aldrich’s bluntness distinguished him from other high-ranking men in the agency who avoided taking sides by perfecting opinions that were elaborate compromises, expressing conviction and doubt in the same sentence.

‘Two kids were almost killed,’ she said.

‘It was unexpected and inopportune. You wouldn’t be human if you didn’t feel terrible.’ Aldrich had been looking at the harbor’s armada when he turned to her. ‘We remind ourselves that we’re honorable men and women who cling to our principles. It’s how we like to think of ourselves when we go to church. We like to believe we’re better than the Russians, or the Syrians, or the Israelis. Maybe we are. Maybe we aren’t.’

Aldrich wore the heavy burden of his job. ‘We go forward. Make another plan to get Qassem. Work with Mossad.’

He moved back inside. She recognized the tricked-out leather attaché case that he put on the table. He turned the key counterclockwise, opening it. Had he turned it clockwise, the usual way of opening a lock, gas jets inside would have incinerated the contents. He lifted the sandwich that was on the top and handed her a manila envelope marked ‘Confidential: Charles Corbin.’

She scanned two pages.

‘Did he tell you he has a wife?’

She stared at the color photo of the woman. Blond hair, gentle smile, full lips. Her physical opposite. ‘Yes.’

‘It’s easier for him to earn your trust if he’s not hiding things, but don’t be fooled by his answers just because he appears to be open. He’s a reporter and happy to play us.’ He paused. ‘I need to know what he is hearing about Israel’s plans. What Mossad is not telling us.’ He looked at her. ‘Did you get into his Blackberry?’

‘I didn’t get a chance.’

‘Don’t let him get too close.’

‘I won’t.’ She was ready to defend her lie as a misunder-standing of the different meanings of the word close, but there was no need. Aldrich had opened a second folder and presented cables with the latest intelligence on Najib Qassem.

‘It’s the update I requested. It will help us figure out the next step.’

‘My tour is over.’

‘You’re exhausted.’ A beat of silence. He met her eyes. ‘It’s tough, I know. Lonely. How’s your marriage?’

She thought a half-truth would answer his question without telling him anything he didn’t already know. ‘We’re talking.’

Agency work had put a strain on her marriage. Her first overseas posting came several months after her wedding. She was sent to Iraq working the non-official cover of an Arabic-speaking Iraqi antiquities dealer to penetrate the ratline Saddam Hussein’s generals used to escape Baghdad. Dirty, treacherous work, and a hard spot for an attractive woman fluent in Arabic. The violent death of a one-eyed colonel had been the finishing touch to a bad assignment – squalid, nasty, dangerous, without any satisfying outcomes except that it kept her away from desk work. The crouched Iraqi colonel had leapt from a hiding place with fierce eyes and a long blade, slashing her shoulder, and she’d killed him with one shot from her Glock. Her cover was blown, and the reward for the kill was to return to Langley and the bleak prison of desk work. She pored over classified cables from diplomats, foreign intelligence agencies, and field operatives, and then synthesized the best stuff into briefs for the DCI and the White House. Meticulous, highly analytical work. The stateside pleasure of time with her husband hadn’t worked out. She discovered that the fondness she’d harbored in his absence became intolerable irritation in the sustained intimacy of domestic life. Twelve months in, her request to return to the field was approved and she was sent to Beirut to join Qassem’s targeting team as a deep-plant HUMINT source, working the non-official cover of an interpreter assigned to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. She left behind her husband and placed her wedding band in a jewelry box for safekeeping.

‘We booked a weekend in Paris before I start in Cairo. We’ll see what happens.’ She looked at him, irritated. ‘I’m not supposed to be here.’

‘And the kids weren’t supposed to be in the vehicle. But they were. We need to finish this,’ Aldrich said. ‘The boy trusts you. He expects you to evacuate his sister. If we’d gotten Qassem, this would be moot, but we didn’t. You can’t leave. Not yet.’

‘I did my part. I found Qassem.’ She shook her head. ‘My cover may be blown. Corbin left three voice messages. He’s curious why I was in Haret Hreik.’

‘What did you tell him?’

‘I haven’t returned his calls.’

‘Avoid him. Keep your distance.’

‘I can’t avoid him,’ she snapped.

Aldrich heard the change in her tone of voice. ‘Give him a reasonable story that will hold up for a couple of weeks. I’ve extended your tour by two months. I’ll make Paris up to you.’

‘So that’s it? I’m being put out there.’

‘You’re already out there.’

Some part of her annoyance showed on her face, and Aldrich’s expression softened. He was quiet for a moment and turned to the open balcony doors where the setting sun glowed warmly on his face. Visible beyond the rooftops, the Mediterranean was an endless canvas of deepening blue. The wind had settled with dusk, and the surface of the water was still, which brought a pleasant calmness to the tension between them. Aldrich had gaunt cheeks, a tanned complexion, and the ascetic aspect of a man who had spent his adult life thinking about an unrepentant enemy. His arms hung at his sides, and his quiet face had the brooding mystery of a Buddha.

‘I also thought of leaving the agency in my early thirties. I was fed up with Langley’s politics, everyone a Cassius waiting for a Caesar. If you didn’t use the knife in your hand, you found it in your back. I resigned and walked out the turnstiles at Langley Headquarters, giving my badge to the security officer. I passed through the sliding glass doors that I’d crossed thousands of times, thinking that I was free. A chapter in my life was over. I was proud of my work, but happy I was leaving.’