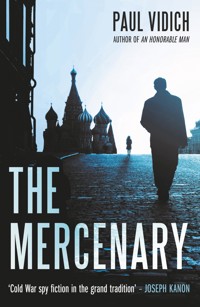

6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

From acclaimed spy novelist Paul Vidich comes a taut new thriller following the attempted exfiltration of a KGB officer from the ever-changing - and always dangerous - USSR in the mid-1980s. Moscow, 1985. The Soviet Union and its communist regime are in the last stages of decline, but remain opaque to the rest of the world - and still very dangerous. In this ever-shifting landscape, a senior KGB officer - code name GAMBIT - has approached the CIA Moscow Station chief with top secret military weapons intelligence and asked to be exfiltrated. GAMBIT demands that his handler be a former CIA officer, Alex Garin, a former KGB officer who defected to the American side. The CIA had never successfully exfiltrated a KGB officer from Moscow, and the top brass do not trust Garin. But they have no other options: GAMBIT's secrets could be the deciding factor in the Cold War. Garin is able to gain the trust of GAMBIT, but remains an enigma. Is he a mercenary acting in self-interest or are there deeper secrets from his past that would explain where his loyalties truly lie? As the date nears for GAMBIT's exfiltration, and with the walls closing in on both of them, Garin begins a relationship with a Russian agent and sets into motion a plan that could compromise everything.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Praise for Paul Vidich

‘A terse and convincing thriller… this stand-alone work reaches a new level of moral complexity and brings into stark relief the often contradictory nature of spycraft’ – Wall Street Journal on The Coldest Warrior

‘With this outing, Vidich enters the upper ranks of espionage thriller writers’ – Publishers Weekly, on The Coldest Warrior

‘In the manner of Charles Cumming and recent le Carré, Vidich pits spies on the same side against one another in a kind of internal cold war’ – Booklist, on The Coldest Warrior

‘A richly detailed work of investigative crime writing perfect for fans of procedurals and spy fiction alike’ – LitHub, on The Coldest Warrior

‘Vivid and sympathetic… a worthwhile thriller and a valuable exposé’ – Kirkus Reviews, on The Coldest Warrior

‘Chilling… more than an entertaining and well-crafted thriller; Vidich asks questions that remain relevant today’ – Jefferson Flanders, author of The First Trumpet trilogy, on The Coldest Warrior

‘Vidich spins a tale of moral and psychological complexity, recalling Graham Greene… rich, rewarding’ – Booklist, on The Good Assassin

‘The Good Assassin has traces of Conrad and le Carré… Allegiances are mixed, moral forces are confused, and the spies are utterly, irredeemably human’ – CrimeReads

‘Cold War spy fiction in the grand tradition - neatly plotted betrayals in that shadow world where no one can be trusted and agents are haunted by their own moral compromises’ – Joseph Kanon, bestselling author of Istanbul Passage and The Good German, on An Honorable Man

‘A cool, knowing, and quietly devastating thriller that vaults Paul Vidich into the ranks of such thinking-man’s spy novelists as Joseph Kanon and Alan Furst’ – Stephen Schiff, writer and executive producer of acclaimed television drama The Americans, on An Honorable Man

‘An Honorable Man is that rare beast: a good, old-fashioned spy novel. But like the best of its kind, it understands that the genre is about something more: betrayal, paranoia, unease, and sacrifice. For a book about the Cold War, it left me with a warm, satisfied glow’ – John Connolly, #1 internationally bestselling author of A Song of Shadows

‘This looks like the launch of a great career in spy fiction’ – Booklist on An Honorable Man

For Ryder, Juniper, and Leo

He had two lives: one, open, seen and

known by all who cared to know…

and another life running its course in secret.

– Anton Chekhov

‘The Lady with the Dog’

(translated by Constance Garnett)

1

Red Square

George Mueller knew that the night ahead would be about stamina. Stamina for waiting, for worry, and stamina for fear. He understood that he had to be ready for the moment, when everything would suddenly change and he would be a man on the run. He wouldn’t get off that roller coaster until the mission succeeded or his luck ran out. Hardened nerves, cold resolve, and a tolerance for nausea were things he would have to possess if he was going to get through the night. He had memorized his route through Moscow and took care to anticipate what could go wrong, knowing that he was no longer a young case officer who could jump off a cliff and hope to find his wings on the way down.

Five minutes after four o’clock in the evening, December 31. Mueller noted the time and date for the report he’d later write. The Agency’s new rules made it important to document an operation, and failure to do so was a poor mark on any case officer’s career, but date and time were important to Mueller for an entirely personal reason. At sixty-three, he was a few months from voluntary retirement. He didn’t want to end his storied career with a failed mission.

The cable from Headquarters that came into Moscow Station had been succinct. The walk-in Soviet intelligence officer who had approached Mueller, throwing an envelope in the open window of his car when he was stopped at a traffic light, was potentially the most valuable Soviet asset to ever offer his services to the CIA. Recruiting the man known only as GAMBIT took precedence over all other activity in Moscow Station.

Knowledge of GAMBIT’s existence was limited to Mueller and John Rositske, his deputy chief of station, who was at the wheel of the Lada. They were next in line to exit the embassy parking lot, and they waited for the marine guard to raise the barrier for the lead car. Neither of the junior officers in the Lada – Ronnie Moffat, who sat in the back next to Mueller, or Helen Walsh, in the front – knew the details of the night’s operation, nor did the case officers in the decoy car being waved through.

Mueller lit a Prima and cracked open his window. The top floor of the embassy’s French Empire façade was singed with dusk’s streaking light, turning the pale stucco an ochre red. Its height set it apart from neighboring Georgian homes along Tchaikovsky Street. Soviet militia stood in guard shacks on both ends of the embassy, using their telephones to call out the comings and goings of embassy staff to nearby KGB surveillance teams. Mueller’s eyes moved to the left, beyond the militia’s shack, toward two parked Volga sedans, exhaust pluming into the bitter cold. Across the street at the bus stop he saw two Russians in quilted-cotton jackets and shabby wool caps drawn over their foreheads sharing a bottle of holiday vodka. KGB? he wondered. Or members of the million-man-strong army of Russian alcoholics?

Gusting wind drove a light snow across the wide boulevard, which was empty of traffic at that hour as Muscovites left work early to celebrate the new year. Streetlamps went on one after another, illuminating the embassy like perimeter lights along a prison wall. Moscow was a city of elaborate privileges for foreigners with hard currency, but to Mueller and the other CIA officers in Moscow Station, it was a denied area – a dangerous place of provocations and surveillance. Mueller alone knew his destination that night. Two vertical chalk marks the day before on a postal box by the tobacco kiosk outside Kievskaya Metro Station had told him the meeting would go on.

Mueller was tall, and his knees hit the back of the small car’s front seat. He wore a bulky Russian overcoat that he’d purchased at a flea market, a pair of thick-soled shoes, and an old fox shapka. He struck a match and relit the Prima, cupping his hands against the breeze coming in his window, and exhaled pungent tobacco smoke.

Mueller had joined the Agency out of the OSS and witnessed firsthand the burgeoning bureaucracy’s reliance on new technologies, but he understood that spy satellites and code-breaking algorithms didn’t substitute for the intelligence that came from the solitary man who gathered secrets at the risk of his life. Mueller’s hair was gray and thinner, his lower back kept him from a good night’s sleep, and he started his morning with a regimen of pills, but he admitted to no one that he was too old to play at the young man’s game. He had circled his retirement date, but he had done that before, and there was no certainty he’d follow through this time. The job had defined him, shaped him in ways he hadn’t expected, and he found it hard to imagine life on the outside. Doing what? Quietly writing a memoir? Fishing? Reading Shakespeare? Looking for ways to stay relevant?

The marine guard raised the barrier. Mueller met Rositske’s eyes in the rearview mirror, and he confirmed that it was time to go operational. John Rositske was Mueller’s physical and personality opposite – shorter, heavier, Catholic, and a man who liked to talk even when it was wise to shut up. He had joined the Agency when it was no longer an exclusive club for eager young minds from the Ivy League. He was in his early forties, coming to the end of his two-year tour, a burly man with a big voice and an outsize confidence. He had red hair and a West Texas tan, which had paled in the long Russian winter, and his eyes, lively and kind at times, were grim coals and relentlessly skeptical on the job. He’d picked up his gruff voice as a teenager working weekends as a ranch hand, and it had served him well during his two tours in the Mekong Delta commanding a marine platoon. He’d led forty-two men on a risky night helicopter assault, which had earned him a Bronze Star and left half of his men dead.

Rositske lowered his window for the marine guard, who checked his State Department ID and glanced in the car.

‘What’s that?’ The guard pointed his flashlight at a cardboard box on the back seat.

Ronnie showed off covered porcelain dishes holding a holiday dinner: aspic, pirozhki, chicken with potato sloyami, and meat patties. She was prepared to give the address of the New Year’s party they were attending, and she also had an explanation, if one was needed, to account for the compressed air canister at her feet.

‘Ready,’ Rositske said after they’d been waved through. Rositske tapped the gas pedal twice to make sure the notoriously unreliable product of Soviet engineering didn’t stall, and he moved the stick shift with his knuckled fist. ‘Rock and roll, gentlemen. Moscow Rules.’

There was only one rule in Moscow anyone could remember, but the plural had survived. Trust no one. Assume every taxi driver, every drunk on a bench, each traffic policeman, and every shy girl in a bar looking for companionship worked for the KGB.

Rositske turned onto Tchaikovsky Street, and in his rearview mirror he saw two black Volgas pull away from the curb. ‘Tics. Far left side.’ He kept to the speed limit, making the second right turn into a neighborhood of narrow streets and once-elegant homes, and he continued at that speed, slowing only to make another right turn and then a left, altering course, and with each turn he confirmed the Volgas still followed. He knew their advantage – high-powered cars equipped with encrypted radio transmitters.

‘Next turn.’

Ronnie threw a blanket off her lap and pulled a deflated, life-size sex doll from the floor, arranging it on the seat, slumped forward. Mueller tested his door handle, rehearsing in his mind a sequence of moves.

Suddenly, the Lada sped up, accelerating into a right turn, and Rositske followed with another immediate right turn, and then a third. As he came out of the last turn, he pulled hard on the hand brake, slowing the car without its brake lights glowing red.

‘Now!’

Mueller pulled the handle, opening the door, and he rolled onto the pavement, hitting hard. His momentum brought him to his feet, and in a split second he had taken cover between a stunted bush with prickly thorns and a parked car. Mueller pressed against the car, gulping air, and he looked at the accelerating Lada. The inflated life-size doll was propped in his seat, the glowing tip of a Prima dangling from her mouth and a fox shapka on her head. Technical Services in Langley had come up with the trick. They purchased the doll and two back-ups in a Washington, DC, sex shop and shipped them to Moscow Station via diplomatic pouch.

Mueller saw the two Volgas speed past unaware of the deception and breathed deeply to prepare himself to go dark. He looked at his watch: 4:17 p.m.

*

Mueller moved along the dark street, keeping to the center of the sidewalk, and passed through circles of light cast by widely spaced streetlamps, just an older man carrying a cloth bag with his holiday meal. He had three hours until his rendezvous with GAMBIT, and while it had once seemed like an unnecessarily long interval, he was glad he had the time to dry-clean himself.

Mueller moved from shadow to shadow in his bulky overcoat with the slack step of a Party apparatchik returning to his one-room apartment to eat dinner alone. His cloth bag held a fresh orange, parsley potatoes, herring, walnut rogaliki, and a small bottle of plum brandy. Under his pensioner’s dinner was tightly wrapped brown paper of the sort used by butchers, and inside a T-50 miniature camera fitted into a ballpoint pen, film cartridges, a tiny burst radio transmitter, and a thick stack of rubles. The cloth bag swung at his side as he walked and from time to time he blew on his gloved hands for warmth. The falling temperature stung his cheeks.

Mueller made his way along grim streets and through drab apartment blocks dotted with lights, beacons of joy for families gathered to celebrate a secular holiday that the Communist Party had elevated over Christmas. He crossed the Moscow River at Borodinskiy Bridge and then doubled back on Kalininskiy Bridge, headed toward Moscow Center. He was alert to movements in his peripheral vision, but he resisted the temptation to look. He had learned not to meet another person’s eyes. If he looked, he knew the stranger would look away. Muscovites kept to themselves, and they knew to mind their own business.

But coming to the end of the second bridge, Mueller happened to stop to light another cigarette. As he shielded his match against the wind, he glanced around. If the KGB were there – on foot or in a car – they had mastered the art of being invisible, and that was the fear of some case officers in Moscow Station. It had been a bad season. A dozen of the Station’s best assets had been arrested, their networks rolled up, and years of patient work wiped out. Everyone had a theory for the loss. Rositske believed the KGB’s new ghost surveillance was a ploy to demoralize Moscow Station. Teams of KGB would wait beyond the visual horizon for hours, giving the appearance there had been a break in surveillance, and then suddenly they would converge in cars or on foot, when the case officer was confident he was dry-cleaned and could go operational.

Rositske advised Mueller not to take an operational role that required a young man’s reflexes and a chess master’s mind. At sixty-three, Mueller had his best years behind him, but the evening’s success depended on more than fitness – it depended on GAMBIT’s trust, and Mueller alone had that.

Mueller flicked his cigarette over the edge of the bridge and watched it fall to the river’s pack ice. He fixed his eyes on Kalinin Prospekt in the distance and beyond that the metro station. Ready, he thought.

The Arbatskaya Metro Station entrance was empty of the usual crowd, and he joined the few people moving down to the platform level. He let himself be pushed by a big, bustling woman who smiled until she got a better look at his face. Mueller was alert to watchful militia teams nearby and the footsteps of passengers rushing to beat the metro’s closing doors. He moved through the vaulted lobby, becoming another submissive Soviet Russian who knew to keep to himself. He shuffled his worn shoes to give the appearance of a diminished older man, someone the militia would judge to be a person of little interest. In this way Mueller passed through the station, emerging on the street at a separate entrance. He glanced back. Clean. It was time.

*

Mueller entered Karl Marx Prospekt on the northwest corner of the Kremlin. Cold darkness lay across Red Square, and he slapped his gloves to warm his hands and prepare for what lay ahead. Not since he’d parachuted behind Nazi lines at night in Occupied France had he been this nervous.

He moved clockwise around the medieval fortress and entered the open square, where the enormous clock and bells of Spasskaya Tower inside the Kremlin wall announced the time. A horizontal band of snow obscured the spire’s red star.

Mueller saw the honor guard goose-stepping out of an archway in the wall, proceeding to Lenin’s Tomb on their hourly rotation. He gazed across the scattered pedestrians who crossed the square, hunched against the wind, trying to stay warm. Mueller looked for a man like himself, dressed in a tired overcoat and shapka, holding a cloth bag in his right hand. GAMBIT had set the time and place of their brush pass, thinking – Mueller assumed – that an open place with people to overwhelm the militia’s watching eyes would be a good spot to converge. This was an amateur’s mind at work, and Mueller knew that GAMBIT’s choice could put them both at risk.

In spite of the bad weather and the late hour, groups of visitors looked toward Lenin’s dark granite mausoleum. Tourists from the provinces and a few foreigners endured the cold to catch the changing of the guard, while others had taken up positions to watch the evening’s fireworks display.

‘Smoke?’

Mueller was aware of the man before he heard his voice, but what unsettled him was the question in English. He turned to face an Interior Ministry militiaman wearing a high-crown cap with the seal of the USSR. He had the stern, self-assured face of a man aware of his authority. Mueller gave no hint that he understood, and his eyes opened slightly. Confusion. The militiaman pumped two fingers to his lips.

Mueller obliged, hitting the red pack of Primas on his sleeve, offering a loosened cigarette.

‘Spasibo.’

Mueller continued toward the Monument to Minin and Pozharsky in front of St. Basil’s Cathedral’s candy-striped domes. Mueller had gone a few steps when he saw the man he knew must be GAMBIT. The time was right, the spot agreed, and the man carried a cloth bag in his right hand. He was dressed like Mueller, so they could pass as doubles – two older men who looked alike on a vector to cross paths by the benches. If all went as planned, they would exchange bags in their brief moment of contact and separate. Only the most vigilant observer would notice that the cloth bags had been switched, Mueller carrying another man’s dinner and GAMBIT carrying camera, film, radio, and rubles. The brush pass would happen in the blink of an eye.

‘Amerikanets!’

Mueller cursed his luck. The militiaman was having fun with him because the night was cold and there was no one else to harass. He continued toward the monument and considered whether to abort.

‘Ostanovis!’ Halt.

Mueller’s world got very small. His choices were usurped by the sudden appearance of a black Volga that emerged rapidly from a side street by the GUM department store. A second Volga entered the square farther away, its wheels skidding on the thin covering of fresh snow, swerving wildly until its driver regained control and headed for Mueller. Third and fourth cars swept in from behind St. Basil’s. Tourists and foreigners gathered at Lenin’s Tomb looked at the four vehicles that raced toward the old man with his cloth bag.

Mueller stood perfectly still. It would be a fool’s errand to run. Plainclothes officers emptied from their cars and advanced on him in a tightening circle. Fuck! It was as if they had known he would be there. Mueller considered GAMBIT, now drawing the attention of a militiaman, and in that moment, he prepared himself mentally for the diversion he knew he must create.

He sprinted toward a narrow opening in the encircling net in a hopeless bid to escape. He was easily apprehended, but he continued to put up heroic resistance, cursing the men holding his arms. He continued his indignant objections until the officer pinning his arm kneed his lower back. A second blow struck the back of his skull. His head began to spin, and he dropped to the pavement. He breathed deeply to shake off the nauseating pain and gather his thoughts. His glove was pulled off and his palm grazed with a handheld black light, revealing dim, amber fluorescence.

‘Mr Mueller.’

A pair of polished black leather boots filled Mueller’s field of vision, and he raised his eyes. As he did, he glimpsed the shapka-capped man with his cloth bag by the Monument to Minin and Pozharsky. The man passed a few more benches and turned for a second, watching the commotion. He looked toward Mueller, a quick glance to take in the scene, and then turned again, walking away, beginning to hurry.

The officer standing over Mueller was of average height with bony cheeks scarred with pockmarks, calm eyes, and a gaunt frame that made him look menacing. Mueller recognized the high-crown gray cap of a KGB lieutenant colonel. Mueller had not met the officer, but he knew the face from Moscow Station’s files. Lieutenant Colonel Viktor Talinov, first deputy to the head of the Second Chief Directorate. Mueller knew he was a brutal man who had been trained by the Soviet system to be a tool of repression. He was known to be precise and quick in his methods – like a good butcher.

Talinov removed the contents of Mueller’s cloth bag and handed them to the KGB officer at his side – the orange, the plum brandy, herring, parsley potatoes, and finally the walnut rogaliki, briefly savoring the dessert’s candied aroma. He complimented its perfection with a knowing nod.

Talinov removed the brown paper package from the bottom of the bag. He undid the twine, unfolded the paper, and looked at the contents. He presented his discovery to his prisoner like an offering.

‘Dolboyob.’ Fuckhead.

Talinov removed his stitched leather glove by pulling one finger at a time, until his long, delicate pianist’s hand was open to the cold. He slapped Mueller’s cheek with the glove.

‘I have been looking forward to meeting you. Unfortunately, these are difficult circumstances.’

Mueller felt the slap’s sting as a prelude to a bruising night. He said what he would repeat many times, in those and similar words: ‘I am an American diplomat. I demand to speak with my embassy.’

2

Greenwich Village (Two Days Later)

The moment Aleksander Garin opened the front door of his West Village walk-up, he knew that his wife was gone. He stood in the vestibule, attaché case in hand, and he felt the dark silence of the empty apartment. Her coat was missing, her purse not where she usually placed it, and there was an envelope pinned to the corkboard where she knew he would see it – the care of a person making sure to tie up loose ends. She had written his name in her big, loopy script.

He moved into the small living room and dropped the envelope on the round dining table. He was reluctant to open it but also eager to know what she’d written, those opposing feelings tugging at him at the same time.

It was snowing outside again. Through the casement window he could hear plows scraping the pavement on their rumbling way down the quiet street. A week earlier they had celebrated his birthday at his favorite restaurant in Little Italy, and he’d commented that the neighborhood had changed, the old places now drawing patrons from the suburbs, but they had still enjoyed the meal, sharing a bottle of Chianti, and they’d made love when they got home. It had been a brave effort to hold on to their intimacy, but when they finished, they lay apart on the bed. They fell asleep without talking.

The next day, he’d gone to work, as usual. When he left the apartment, she was at the round table writing an outline for an article she was pitching to editors, and she hadn’t looked up to say goodbye even though, as previously planned, she would be off to visit her parents in Los Angeles for the weekend. She had returned from Los Angeles on the Sunday night red-eye, missing him before he left for the office, but she’d been waiting for him in the kitchen when he got home Monday night. They had talked, and then the argument had begun. It started with a small thing, as all their arguments did, and he couldn’t remember what had taken them down the path of blame and recrimination, but once there, they were unable to stop. Heated emotion eventually exhausted them and, just before going to bed, she had said it was over.

*

‘Sophie?’ He didn’t expect her to answer, but he thought it advisable to confirm she was gone before he read her note. He lifted it, holding it like an unwanted gift. She had written Aleksander on the envelope, addressing him as she occasionally did, but only when she was being formal, or serious, or when Alek wouldn’t get his attention. She had used Aleksander in their marriage vows, in heated arguments, and once when he’d been hit by a taxicab.

He opened the envelope. When he finished reading, he refolded the stationery and placed it back in the envelope and laid it on the table, as if that was where it belonged. He made himself a gin martini and drank half. Looking up, he happened to see his reflection in the beveled wall mirror above the breakfront. He was a little stunned, a little tired, but there was no surprise on his face and no sadness in his expression. He knew that would come later. After all, the end of a relationship was a kind of death, and sadness accompanied death. He finished the martini and made another.

Things between them had not been good for some time. His hours were long, his absences unpredictable, and his work a black box that he didn’t discuss. When they’d first met, he had laid out the reasons why he would be a terrible partner, but she had ignored his warning, believing she could change him. They had discovered the challenges of day-to-day living in the first months of marriage – lost weekends, urgent calls, and the mystery of his sudden out-of-town trips. What had seemed acceptable in the fresh blush of romance became unbearable in marriage. He believed that she cherished him, and she said she did, and there was a time when his privacy was safe from reproach. They had loved, made love, enjoyed the fullness of their feelings, and seized carefree moments. God, how he had wanted a normal life with her.

Garin turned away from the mirror. He walked to the bedroom and switched on the light. Everything was in order. The bed perfectly made, each vacation photograph squared on the wall, fluffed bed pillows arranged as she liked them. It was an odd thing, he thought, to leave the room in perfect order at the moment of her flight. There was a part of her he’d come to discover that needed predictability, order, safety. His work had none of that. When they understood this, they both knew the marriage was doomed. For a long time they refused to admit they’d made a mistake. He had known her as well as he’d known any person, but now, seeing her gone, he wasn’t sure he’d known her at all.

She had taken some clothes, and when he checked her jewelry box, he saw that she had taken a pair of heirloom earrings and her pearl necklace. There were empty hangers in the closet, and her rolling suitcase was missing.

He opened his desk drawer and felt underneath. Tape fixed the hidden manila envelope to the bottom. She hadn’t found his documents, or hadn’t looked. He removed the envelope and confirmed that the seal was unbroken. He tossed it on the bed.

Garin moved to the kitchen and stood at the sink, looking out into the dark, snowy night. He drank a glass of water and saw his reflection in the mirrored smokiness of the window. His hand was trembling. The glass fell, shattering in the porcelain sink, and a shard pierced his palm. He bled out the cut under the faucet’s cold water.

Suddenly, the telephone rang, startling him. On the second ring, he lifted the receiver.

‘Sophie?’

‘Alek Garin, please.’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m James Slattery. I am with the Agency. I’m calling on a secure line. Are you alone? Can we talk?’

‘I’m alone.’

‘I’m calling at the request of the deputy director. Sorry to bother you at this hour. There has been a problem in Moscow. Your name came up. We have a request for you.’

Garin’s eyes came off the snow falling out the window. His silence was a sort of consent.

‘Is there anything that will keep you from flying out of JFK the day after tomorrow?’

Garin closed the faucet and put pressure on his cut, cradling the phone against his neck. Sophie’s sudden departure and the surprise call combined to create a surreal sense of displacement. He knew he couldn’t live alone in the apartment. Memories in the familiar place would be a terrible reminder of their failure. His mind went over the half-dozen ties that would prevent him from going. ‘When do I have to decide?’

‘Now, actually. On this call. It’s an urgent matter. The Air France flight leaves at 5:00 p.m. We can have a car pick you up Wednesday afternoon. The driver will brief you.’

‘How long?’

‘Stopover in Charles de Gaulle for a further briefing. From there, you will fly to Sheremetyevo. You’ll be in Moscow in seventy-two hours.’

‘How long will I be gone?’

‘We’re not sure at this time. Weeks, certainly. Months, perhaps.’

‘The money?’

There was a pause. ‘We are prepared to deposit twice your usual fee in the account you’ve used in the past.’

The offer surprised him, not simply because of its size but because the amount implied the seriousness of the matter, and possibly also the risks. One day earlier, the danger would not have appealed to him.

He looked around the apartment. This was to have been his new life, but there had never been an end to work’s demands, and never enough money. Contract jobs paid well enough, but they were unpredictable. He’d stuck with it because the work had never been just about the money. He had a figure in mind – the amount he needed to start over in another city.

Garin wrote two numbers on the notepad that hung by the wall telephone. He gave Slattery the larger number and was prepared to accept the lower, but that wasn’t necessary. When the call ended, Garin placed the handset in its cradle and considered all that would now follow.

Garin entered the bedroom and lifted the manila envelope, tearing the seal. His American passport was the logical choice for the job – the name matched his driver’s license, and it was the name on his marriage certificate – but there was also good reason to use the name that appeared on his Soviet passport and his birth certificate. He looked at both passports, considered where he was going, the risk of being stopped at immigration, and made his choice.

3

Moscow Station

Sheremetyevo International Airport’s weather was unseasonably warm the morning that Garin stepped off Air France 1744. Winter fog was deep and gray on the tarmac, and it turned aircraft into ghost machines. His overnight flight from Paris was the last to land before air traffic controllers announced a ground stop. Passengers walked in the light mist from the plane’s remote location to the new terminal under the watchful eyes of armed border guards. Garin was alert to the surveillance, becoming for the moment another fatigued passenger happy to get out of the rain.

When it was his turn at immigration, he presented his American passport and forged visa to a stern, middle-aged officer with bloodshot eyes, a loosened necktie, and a mysterious badge on his uniform. He looked twice at Garin’s visa, matching photo to face, comparing the likenesses with the inscrutable expression of immigration officers everywhere, looking for a single reason to doubt the documents. Garin followed the example of other passengers, who did as they were told, moving from one queue to the next, until they extracted their bags from the carousel’s conveyor belt. He opened his bag for the customs agent, who poked through his underwear and then waved him through to the glass lobby.

The embassy driver sent to collect Garin stood beyond a roped perimeter that held back eager parties waiting to greet arriving travelers. Garin nodded at his handwritten name on the driver’s card and let the driver take his duffel bag.

Garin didn’t talk on the drive in. His mind was preoccupied by the view from the car’s window. The dense fog had lifted enough for him to see landmarks he thought he’d never see again – the brutalist architecture of grim apartment blocks, wispy coal smoke that rose straight into the air, and the sameness of the cars. How many times had he driven this route, the exact drive? There was something illusory about time and space that in the moment made him feel as if he’d never left the Soviet Union. The low visibility darkened his mood and reminded him of the morning he had been forced to flee. It still haunted him that he hadn’t seen, or chose to ignore, the obvious dangers. His wishful thinking had blinded him to the treachery of men he trusted, and it was only when he’d gotten out that he had time to reflect on what had gone wrong. On instinct, he looked behind and saw a black Volga following.

‘They’ve been there since we left the airport,’ the driver said, catching Garin’s eye in the rearview mirror.

Nothing has changed, he thought. But things were different. He was older, with a scar on his neck, another name, and a new assignment.

*

Garin was six feet, and slender for his age, which made him appear younger than he was, and his knees hit the front seat. After thirty-six hours of airport lounges and coach travel, he was exhausted, and he looked it. His cheeks had the rugged shadow of a hiker just back from a four-day trek. It was a masculine face but not a tough face, and fatigue had darkened his preoccupation. His slacks had lost their crease, his shirt was gray with perspiration, and his wide tie was loosened at the neck and fell across his chest like a lanyard. When he saw the embassy, he tightened the necktie’s knot and swept back his hair.

‘We’ve been expecting you,’ Ronnie Moffat said when Garin stepped from the car at the embassy’s side entrance. ‘I’ll bring you up.’ She hustled Garin past the marine guard.

Moscow Station was a cramped suite of rooms on the seventh floor. Bricked-up windows gave the vestibule they entered from the elevator a claustrophobic feeling. The small room served as a kind of air lock in which non-Agency personnel were allowed to read classified material. They moved toward a door without a handle or keyhole and no opening except a peephole for those inside to see who wanted to enter.

‘Listening devices were found in the beams,’ Ronnie said, noting his wandering eyes. ‘Two years ago, an electric typewriter had to be quarantined. We found a KGB microprocessor under the typewriter’s keypad that recorded each stroke and sent the data to the power cord, which transmitted it wirelessly.’

She swiped her badge against the electronic wall pad, causing the door to swing open automatically, and they entered a long, crowded area of cubicles and cramped offices. Overnight cipher clerks transcribed and decrypted coded messages from Headquarters, working reverse shifts to accommodate the time difference. Little had changed, Garin thought, as he stepped into Moscow Station, calibrating what he remembered against what he saw.

Ronnie pointed to a conference room that was encased in inch-thick Plexiglas. ‘Secure conversations take place there. We call it the Bubble.’

‘Aleksander Garin,’ she announced, opening the conference room door.

George Mueller sat at one end of a long conference table, and next to him was another man Garin did not recognize. Garin nodded at each one, but he settled on Mueller. Mueller’s right eye was a purpled spider web, which gave him the look of a man who had been on the losing end of a fistfight, and his left hand was splinted and bandaged. Mueller’s overcoat draped a chair, and his bulky garment bag leaned against the wall. An airplane ticket, his black diplomatic passport, and an open file lay in front of him on the table.

‘Your car is ready to take you to the airport,’ Ronnie said.

‘When I’m done here,’ Mueller replied, and then he looked at Garin. ‘Sit down. You keep looking at my face. You’ve never seen the KGB’s handiwork? It could be worse. I’ll have it looked at in Washington.’ He nodded. ‘Yes, I’ve been declared persona non grata and expelled. This is my deputy, John Rositske.’

‘Long trip?’ Rositske said.

‘No more than usual.’ Garin met Mueller’s eyes without acknowledging that they knew each other. He turned to Rositske. ‘Just the two of you?’

‘For now,’ Mueller said. ‘Surveillance?’

‘One car. They dropped back when we crossed the bridge.’

‘Immigration?’

‘No trouble.’

Garin saw Rositske stare at him like a bored house cat watching a sparrow through a window. ‘What?’

‘Your name?’ he said. ‘I drew a blank when your name came through on the cable from Headquarters. I read that you’re a native Russian speaker. That surprised me. I’m familiar with all the case officers in the division who work on Soviet affairs. I’ve never come across your name. How is that possible?’

‘I don’t work in the SE Division.’ Garin took a measure of the two men opposite. He flattened his accent to rid it of clues of who he was or where he was from, and he gave an account of the phone call and the details of his departure from New York, leaving out only personal details that weren’t germane. Garin had mastered the art of separating life and work. He spoke about the trip with the calm of a man who long ago had surrendered his will to the sudden demands of unpredictable covert work. ‘I was told there’s a mess to clean up.’

‘We don’t have a mess,’ Rositske said in his Texas drawl.

‘There was another breach,’ Mueller interrupted. ‘The KGB knew I would be in Red Square.’ Mueller folded his hands on the table solemnly. He nodded at late-arriving staff coming through the peephole entrance door. ‘That’s why we are in here. It’s just the three of us for now.’

Coffee was brought in. Garin took his black with four sugars that he measured carefully, stirring slowly counterclockwise, and then he drank it all at once. He listened to Mueller describe the Station’s loss of MOBILE, PANDER, and two others he didn’t identify.