Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

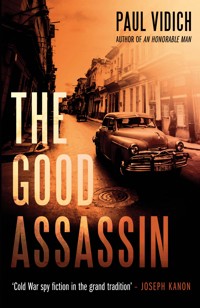

Paul Vidich follows up his acclaimed debut spy thriller with a suspenseful tale of Cold War espionage set in 1950s Cuba, as foreign powers compete to influence the outcome of a revolution. Paul Vidich follows up his acclaimed debut spy thriller with a suspenseful tale of Cold War espionage set in 1950s Cuba, as foreign powers compete to influence the outcome of a revolution. The CIA director persuades retired agent George Mueller to go to Cuba during the perilous last throes of the Batista regime to investigate Toby Graham, a CIA operative suspected of assisting Fidel Castro's rebel fighters with diverted CIA weaponry. Posing as a magazine travel writer, Mueller reconnects with Jack and Liz Malone, old friends who have relocated to Cuba and are unable to see the coming upheaval in their lives, both political and personal. Toby's betrayals aren't limited to his mission, and Mueller must make a choice between justice and duty, between loyalty to his profession and to his friends. Paul Vidich has written a powerful story of ideals, passions, betrayals, and corrupting political rivalries in the months before Castro's triumphant march into Havana on New Year's Day 1959.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 346

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

GOOD ASSASSIN

Paul Vidich follows up his acclaimed debut spy thriller with a suspenseful tale of Cold War espionage set in 1950s Cuba, as foreign powers compete to influence the outcome of a revolution.

The CIA director persuades retired agent George Mueller to go to Cuba during the perilous last throes of the Batista regime to investigate Toby Graham, a CIA operative suspected of assisting Fidel Castro’s rebel fighters with diverted CIA weaponry. Posing as a magazine travel writer, Mueller reconnects with Jack and Liz Malone, old friends who have relocated to Cuba and are unable to see the coming upheaval in their lives, both political and personal. Toby’s betrayals aren’t limited to his mission, and Mueller must make a choice between justice and duty, between loyalty to his profession and to his friends.

Paul Vidich has written a powerful story of ideals, passions, betrayals, and corrupting political rivalries in the months before Castro’s triumphant march into Havana on New Year’s Day 1959. This sequel showcases the widely praised talents of Paul Vidich, who Booklist says, ‘writes with an economy of style that acclaimed novelists might do well to emulate.’

About the author

Paul Vidich has had a distinguished career in music and media. Most recently, he served as Special Advisor to AOL Inc and was Executive Vice President at the Warner Music Group, in charge of technology and global strategy. He serves on the Board of Directors of Poets & Writers and The New School for Social Research. A founder and publisher of the Storyville App, Vidich is also an award-winning author of short fiction. An Honorable Man is his first novel.

Praise forAn Honorable Man

‘An Honorable Man is an unputdownable mole hunt written in terse, noirish prose, driving us inexorably forward. In George Mueller, Paul Vidich has created a perfectly stoic companion to guide us through the intrigues of the red-baiting fifties. And the story itself has the comforting feel of a classic of the genre, rediscovered in some dusty attic, a wonderful gift from the past’ – Olen Steinhauer, New York Times bestselling author of All the Old Knives

‘Cold War spy fiction in the grand tradition – neatly plotted betrayals in that shadow world where no one can be trusted and agents are haunted by their own moral compromises’ – Joseph Kanon, New York Times bestselling author of Istanbul Passage and The Good German

‘A richly atmospheric and emotionally complex… tale of spies versus spies in the Cold War… Vidich writes with an economy of style that acclaimed espionage novelists might do well to emulate. This looks like the launch of a great career in spy fiction’ – Booklist starred review

‘Paul Vidich’s tense, muscular thriller delivers suspense and intelligence circa 1953: Korea, Stalin, the Cold War rage brilliantly, and the hall of mirrors confronting reluctant agent George Mueller reflects myriad questions: Just how personal is the political? Is the past ever past? An Honorable Man asks universal questions whose shadows linger even now. Paul Vidich’s immensely assured debut, a requiem to a time, is intensely alive, dark, silken with facts, replete with promise’ – Jayne Anne Phillips, New York Times bestselling author of Quiet Dell and Machine Dreams

‘An Honorable Man is that rare beast: a good, old-fashioned spy novel. But like the best of its kind, it understands that the genre is about something more: betrayal, paranoia, unease, and sacrifice. For a book about the Cold War, it left me with a warm, satisfied glow’ – John Connolly, #1 internationally bestselling author of A Song of Shadows

‘A cool, knowing, and quietly devastating thriller that vaults Paul Vidich into the ranks of such thinking-man’s spy novelists as Joseph Kanon and Alan Furst. Like them, Vidich conjures not only a riveting mystery but a poignant cast of characters, a vibrant evocation of time and place, and a rich excavation of human paradox’ – Stephen Schiff, writer and co-executive producer of The Americans

For Joe and Arturo, with love

‘Blessed are the dead

that the rain falls on’

– F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Great Gatsby

PART I

1

WASHINGTON DC, 1958

It was all set in motion over lunch at Harvey’s when the director made a casual request that caught George Mueller off guard. The request came out of nowhere in the midst of the director’s rambling on about the unfortunate state of affairs in Cuba. Mueller thought it an odd, but harmless favor, and it didn’t require anything of him that he wasn’t willing to freely give – but still it was unexpected.

‘Toby Graham is a good man and good men are hard to keep. They get tired, or fed up with the goddamned bureaucracy we’ve become, or squeamish about the work, or they want a bigger house. They move on. We think he is leaving us. I want to know what’s on his mind.’

It was noon. Mueller remembered the time well. The restaurant was empty at that hour and the director, who arrived early to the office, had taken to lunching before the place filled with a boisterous crowd of eavesdropping Capitol Hill staffers. The director had drained his second gin martini right after the first.

Mueller had come down by train from New Haven for their annual lunch, which had started the year he left the Agency, and now five years on had devolved into a quaint ritual. Mueller didn’t allow himself to look interested when the request came. He didn’t want to give the director the satisfaction of seeing truth in his prediction that Mueller would become bored teaching privileged undergraduates, so he let the director make his case at length. Mueller listened indifferently and his expression had the flat affect of a judge at trial. The director held the last olive in his snaggletooth and withdrew the flagged toothpick, which he stuck in the warm French bread neither of them had touched. He slid an oyster into his mouth. He wore a slate blue suit with crimson pocket square and matching bow tie. He was older, but his effort to dress fashionably was young, and smart rimless spectacles rested on his thick nose. His gray hair had thinned and whatever he’d lost on his head now erupted from his eyebrows. The director shifted the conversation, as he was wont to do, to the unrelated topic of college teaching, going on at length on his theory of pedagogy.

‘And that too,’ the director said suddenly, ‘is why I asked you here. You know how a man can change. Even the best of us miss the signs, and then when we see them we don’t know whether to promote the change or contain it.’

Mueller didn’t find the director’s remark surprising. It was just like him to be vague and Mueller didn’t take the trouble to respond.

‘It’s a small assignment,’ the director said. ‘A small favor. Probably a week of your time. You’ll get paid well. I can be generous with people on the outside, and I’m sure you can use the extra income. Nothing dangerous or scandalous,’ he assured Mueller.

‘What’s on Graham’s mind?’ the director repeated laconically. The emphasis implied by the repetition belied the casual tone of his voice. ‘That’s what I want to know. What’s he thinking?’

‘Thinking?’

‘Is he happy? You know him, don’t you?’

Mueller did know Graham. They’d been undergraduates together, where they met racing sculls, matched against each other on the Thames and the Connecticut River, beginning as rivals and remaining that way through the war, and then as colleagues in Vienna in ’48. The director had their file and would know their history.

‘I need someone I can trust,’ the director said. ‘Someone he will trust. Not an insider. Friends?’

‘Friendly enough to grab a drink after work.’

‘You still on the wagon?’

Mueller hated that phrase. What wagon? And why was being on the wagon synonymous with being sober? He was inclined to challenge the director on his choice of speech, but he knew wisdom in the English language lay in the simile, so he casually repeated, ‘Still on the wagon.’ He lifted his half-finished Coca Cola to prove his claim. ‘Wine occasionally.’

‘Campus life has been good for you. I don’t trust men who won’t drink with me.’

Mueller had heard the director use the line before. It was one of those repetitions that came unconsciously, and if you knew the person long enough you knew it was a tic that came out like a prejudice, but now the director’s words lacked his usual cheerful mocking tone. He seemed preoccupied.

‘We need to know what’s on his mind,’ the director said again. ‘You’re familiar with his type of work.’

Mueller didn’t need an explanation, for these things were known among the men who shared the fraternity of intelligence. To ask a question was to suggest a suspicion. Trust was the fragile bond that held them together. Agents did things that made them useful in the field, but memories were dangerous with men who left, retired, or were forced out. Details of covert operations. Compromising reports of unfortunate mistakes. The truth beneath plausible denials. Agents stuck together, but that was not who Mueller was. He had stayed away from his old colleagues except for his annual lunch with the director.

‘We can’t erase a man’s memory, but we can judge his loyalty.’ The director looked at Mueller and an evanescent smile broke through his grim visage. ‘He may want to take time off. Like you. He’s been working hard.’

The director lowered his voice as two Capitol Hill staffers walked by, and he leaned toward Mueller, close enough for Mueller to smell the cloying alcohol. His cheeks had a rosy, happy blush. Mueller thought the director had aged in the intervening year – gained weight, eyes dimmed, lost his smugness – worn down by the bitter rivalries among temperamental politicians who called him to confess before closed-door congressional hearings.

‘You will work with the FBI’s man in Havana. Frank Pryce.’

The director pushed a file toward Mueller, and Mueller didn’t push it back, which was a mistake. When he saw the yellow-stamped ‘top secret’ and ‘eyes only’ he found himself uncomfortably reluctant to give them up. An old adrenaline conspired against his hesitation.

‘We’ve gotten over the rivalries,’ the director said. ‘That soap opera doesn’t play well with the White House. We won the turf war so now we can be magnanimous. They can be useful here. If there is a success they can take credit and we won’t have to dirty our hands.’

The file before Mueller described Pryce’s discovery – suspicion, the director amended when he saw Mueller raise an eyebrow.

‘Pryce believes the arms embargo against Batista has been breached. Weapons are getting through. There has been a lot of self-righteous chest-beating on Capitol Hill that we put guns in the hands of a dictator who turned them on his citizens. Congress and the press whine that our State Department’s noble intentions with the embargo came too late, offered too little. That we’re coddling a tyrant.’ The director smiled. ‘Our public outrage against dictators we secretly prop up is one of our glorious hypocrisies.’ He licked the last drop of gin from his glass. ‘Pryce thinks it’s Graham.’

The director looked at Mueller. ‘Pryce won’t give his sources. The mob? Hotel wiretaps?’ The director arched an eyebrow. ‘I want to know what Pryce knows. I want to know what he thinks is going on.’ He nodded. ‘You try and find out.’

He popped the last olive in his mouth. ‘We can’t be ostriches about this. Has Graham become a risk? Has he gone around the embargo on his own? We hire good men and give them latitude. It goes without saying that Graham shouldn’t know we are asking questions.’

Mueller tolerated the director’s continued presumption that he’d take the assignment, and he knew that each time he didn’t object he compromised his ability to decline.

‘Pryce will have the details. He knows what we want. Batista’s people are in the dark.’

Disdain and scorn rose in the director’s voice when he mentioned the Cuban dictator by name. ‘Abjectly corrupt. A fat worthless head of state. God knows how we pick our allies.’

Mueller didn’t agree to the assignment at their lunch, but his silence was confederate to the director’s request. He knew one week was an impossibly optimistic estimate of the time he’d be in Cuba, but the idea that he would escape campus lethargy had tart appeal. His sabbatical was upon him, but he’d lost interest in his research on the puns and paradoxes in Hamlet, a lively but binocularly narrow topic, and he was out of sorts with his life. He had arrived at New Haven and was disappointed by the petty academic squabbling, and in his first year he had found that he had time on his hands, was prone to being morose, and longed for the clarity of his old job. He poured his deep ambivalence about the conduct of the Cold War spy game, and how it sacrificed good men for abstract principles, into two paperback novels that were transparently autobiographical, thinking it was a way to make a little money. Teaching and his writing had been a retirement that appealed to his solitary personality, but in time he saw himself as his ex-colleagues saw him, a middle-aged man who belonged to that tragic class of spy prematurely removed from the game – for whom academic life thickened the waist and atrophied instincts. A chess master suddenly withdrawn from a championship match to a rural Connecticut life.

Mueller had stood back from campus life, as he had learned to do in the field, but being an outsider – essential for a spy – made it hard to be a civilian. He’d been appalled to discover that he’d exchanged the rank hypocrisy of Agency work for petulant campus politics.

‘I’m happy where I am,’ he said to the director. They stood on the sidewalk outside Harvey’s. ‘I don’t have the time for this.’

‘If he is your friend,’ he said, ‘you should do this. Lockwood made your arrangements.’

They parted quietly. The sun was high. Its lurid glare scorched the street. They walked in opposite directions into the sparse population out in Washington’s oppressive humidity. Mueller was lanky and handsome, but nondescript in a gray suit, and boyish even in his robust middle age. He felt no urgency in life and no zeal, at least not any longer, and all this gave him a blandness that didn’t draw the stranger’s eye as he strolled to Union Station.

*

Mueller met CIA Inspector General Lockwood a week later in the Rockefeller Center offices of Holiday magazine. Lockwood knew the editor, an old OSS colleague who’d agreed to hire Mueller to write an article on Havana’s night life so he’d have a cover story.

It was a lunch meeting in a private dining room on the thirty-eighth floor that looked north to Central Park. Throughout the one hour Mueller’s eyes drifted to the panoramic view of that great rectangle of landscape design wedged between Fifth Avenue’s Beaux Arts mansions and Central Park West’s gothic co-ops. A shoebox of greenery, he thought. Mueller looked for the metaphor in things. The right image, he told his students, was an aid to unreliable memory.

‘George?’ Lockwood said. ‘You’re distracted. We need your full attention if you’re going to be a success here.’

Mueller took his eyes off the canopy of trees. ‘Thinking about Graham.’

Mueller had met Lockwood when he was division chief positioned for a senior leadership role in the Agency, and then he contracted polio during a trip to Asia on Agency business that left him paralyzed from the waist down. He was a protégé of the director, who accommodated his handicap and made him inspector general, a fittingly senior staff job and suitable for a man confined to a wheelchair, but a dead end. Mueller had been impressed by Lockwood’s stoic dignity. Not once had he seen the man angry, resentful, or depressed. He was the same lanky WASP with his spit of unruly blond hair he brushed from his forehead, but all of him was now compressed into a black mechanical chassis he wheeled around with gloved hands.

‘You were talking about the FBI,’ Mueller said, looking at Lockwood, who was opposite him at the dining table laid with serviettes, silverware, bone china, and a flower centerpiece. Mueller met Lockwood’s skeptical gaze with a benign smile. Though he disapproved of the FBI’s aggressive tactics, and their altogether too heartfelt policing, he had it in him, he said, to cooperate. Dignity, formality, self-restraint. Gifts he allowed himself to believe he had. ‘I can work with them. We’re all mature here.’

Mueller knew that Lockwood performed liaison work with the FBI through the president’s Foreign Intelligence Agency Board, and he was the architect of a rapprochement between the CIA and the FBI. How had he put it on their way up the elevator? ‘Intelligence has to be divorced from police work otherwise a Gestapo is created. We are separate but we cooperate. We’ve got the president yelling he wants someone to tell him what the hell is going on in Cuba. There are people from all over the place, different agencies, different interests, including the FBI, telling him different things, so this is all about that.’

This? Mueller had asked.

‘The FBI is in Havana bugging hotel rooms where the mob stays – Lansky and Stassi and Trafficante. Taped conversations that the FBI makes into transcripts. They don’t know that we know, and they don’t know that we’ve discovered through our own channels that they think we may be responsible for those weapons. You can’t imagine the shit storm in the White House if the director of the FBI walked into the Oval Office with secret recordings that showed one of our assets was ignoring the State Department embargo. We are staying close to the FBI. Friends close, enemies closer, right, George?’

‘A bunch of spleeny dog-hearted farts.’ This from the editor.

Mueller turned to the man seated prominently at the head of the table. He almost laughed. As the one not drinking, Mueller was aware of the volume consumed by the other two. Mueller wondered how the editor would do anything productive when he got back to his desk. He had heard the man’s voice deepen with alcohol and then his humor had thickened too. He was a corpulent man, with thinning hair and piercing blue eyes. Lockwood had given Mueller background on the editor during the elevator ride. He was part of the original OSS contingent who’d come over to the Agency and chafed at the new rules. He became fed up with the growing bureaucracy and was deeply ambivalent about the conduct of the Cold War, and he’d left after the Korean Armistice, taking with him his resentments, his drinking, his opinions, which he offered freely as an editor – and he had his targets. He despised the head of the FBI and denounced him as an incontinent paranoid. England was another target for his readers: ‘Crumbling cold water castles not fit to sleep in.’

The editor looked at Mueller. ‘I read your book. The writing is tolerable. Good enough for us. I’m looking for color on that worm of an island that sits below the Florida Keys.’ The editor said he needed a new angle. ‘Everyone says it’s dangerous, but our readers want to visit and they need to believe it’s safe. They want a week in the Caribbean away from humdrum lives – to gamble, to drink, and to watch erotic floor shows – the taste of scandal they don’t get at home.’

The editor winked at Mueller. He added sternly, ‘I don’t want a police report with body counts. Advertisers won’t pay for that. Don’t invent anything, of course, but you don’t have to harp on the bombings. Isn’t that guy Castro stuck in the mountains?’

The editor rang the waiter’s bell. Lunch was over. He finished the conversation with a suggestion. ‘Hemingway is there in Finca Vigía. Find out what he thinks of Castro. He’s a man dedicated to his art and has an equivalent dedication to everything he does, his fishing, his drinking, and he’s a serious guy who is horrified by the shoddy, the fraudulent, the sentimental, the haphazard, the immoral. So, he is a man of strong opinions and he must have an opinion on Castro. Put the question to him. I’ll double your word rate if you get a quote out of him.’

*

Within the week George Mueller found himself aboard PAN AM Flight 29 with two reporter’s notebooks, a letter of introduction, and the ambiguous comfort of a return trip ticket traveling to that season’s war zone. Toby Graham was in Mueller’s mind when Idlewild Airport sank beneath the airplane, and he was still in his thoughts hours later when the stewardess nodded at his empty glass. ‘Last call.’ She pointed out the window. ‘The Sierra Maestra.’ She took a moment to chat and guessed he was a lawyer, which he was not. She pegged his age at forty, which was close, and she thought he was married, which was half right. Divorced years before. ‘The Tropic of Cancer is there,’ she said. ‘We are a tropical country, but there it is alpine.’ She pointed to the east at the deep green toupee of hunched peaks penetrating the low cloud cover.

Mueller looked down. A vast savanna opened up below the plane and the overriding impression was of a linear order imposed on the land by dirt roads and barbed-wire fences formed into rectangles of pastureland. Geometry imposed on the land was broken where ancient flows gave meandering course to streams that fed a larger river. And then a change in air pressure and he knew their descent to Havana had begun.

The stewardess took his empty glass. Yes, she had come on to him, but when he showed little interest, she walked away and his thoughts returned to Toby Graham. For all his hours of contemplation during the flight, Mueller had no better insight in the stubborn question the director had raised. Graham was a man shaped by espionage. He’d made an early reputation turning ex-Nazis and sending them back into East Germany. Some of them survived long enough to provide intelligence on Soviet military installations, but most were promptly caught and executed. Graham took to the practice of spying. He drew diagrams, planned covert operations, seemed to live in a continuous state of emergency, planted in their cold office in West Berlin most days for ten or twelve hours, or running off to Tempelhof Airport. He jogged in the morning. Drank in bars until late. Mueller saw these surface details in his mind’s eye like a photograph that didn’t open up – revealing little of the inner man.

2

DAIQUIRIS AND BOMBS

Drenching rain pulled a veil over the face of the city. Mueller stood just inside the bar’s door, as did a jolly, middle-aged American couple, who had also been caught in the sudden downpour and laughed brightly at the indignity of their misfortune. One week in Havana had bronzed Mueller’s face and worn thin the novelty of the place.

He slapped his sturdy straw hat against his thigh, knocking off water, and his darting eyes made a confirming survey of the customers. Ever since he’d left the Agency Mueller had tried to unwind his habit of surveying a bar before he sat down, but now he was glad he had the old habit. His eyes drifted from one table to the next, as he raked his hair, taking in each face to see if he knew the person, or to discover if a customer took an interest in him, and if one did, because of some chance encounter, Mueller was prepared to account for his presence, and he had an explanation ready.

It was too early for cocktails, except for the sullen man alone at the bar, whose drinking had no clock, and several sailors on shore leave from the U.S. Navy frigate anchored in the harbor. Across the room half a dozen Cubans were gathered around a table, and they had taken notice when Mueller arrived, but they’d gone back to their conspiratorial whispers. A radio played ‘Volare.’

Mueller glanced at his watch. Toby Graham was late. Graham had been abrupt on the phone – after he got over his surprise – and he asked if they could talk in person at El Floridita. One of those shoddy Havana saloons where the food is cheap and the drinks generous. The word ‘shoddy’ had stuck in Mueller’s mind, and it repeated itself as he took in the place. Red velvet cushions on the banquettes were worn thin, or missing, and the ceiling fan made a labored squeak with each slow revolution. Framed celebrity photographs hung askew on a wall of flies.

Mueller’s eyes wandered across the gallery of Hollywood actors. He liked to think of himself as someone who could both quote Hamlet and put a name to that year’s popular movie stars. His little private conceit. There was Errol Flynn from The Sea Hawk, a movie he knew only by reputation, and there was Ava Gardner, her bare shoulders and alluring smile from The Killers, which he had seen, but had not liked. And he picked out John Wayne, George Raft, Stewart Granger, Orson Welles, Deborah Kerr, Richard Burton, and he felt good about his score, but then he stopped at the last photograph. There was a burly man, bordering on heavy, on a dock, whose face was obscured by the shadow of a wide straw hat.

‘Hemingway,’ a voice said. ‘He’s standing next to a big dead fish.’

Mueller turned. He recognized all at once the buzz-cut, the wrinkled white linen suit, the big man thick in the waist like a tree trunk who stood before him as if he’d taken root.

‘You look surprised. Some people aren’t good with names.’

‘Frank Pryce,’ Mueller said civilly.

Pryce laughed. ‘I meant Hemingway. I suppose you could have forgotten my name.’

Mueller didn’t let Pryce see that his surprise had nothing to do with names.

‘Grab a drink,’ Pryce said. ‘Wait out the storm. Or a sandwich, if you haven’t eaten.’

Mueller struggled with the algebra of rudeness, but the FBI man coaxed him forward and Mueller found himself face-to-face across a table with the one man with whom he didn’t want to be seen. He glanced at his watch again. Think.

‘Papa Doble,’ Pryce said to the waiter who’d appeared as soon as they were seated. ‘Papa Doble. Understand? Comprende?’

Mueller waved off an order when the waiter looked at him.

‘I’m not interrupting anything, am I?’ Pryce asked.

Mueller shook his head rather than invent a lie. Pryce had the square jaw of a high school linebacker who’d gained weight in a desk job. A small gut folded over his tightly cinched belt and his linen suit had darkened from moisture. Beads of sweat dotted his hairline and his teeth clenched a cigarette that looked small on his puffy face. Mueller had formed a view of Pryce in their one meeting, and this second encounter reinforced the first impression that Pryce was of that loud class of overseas Americans who felt entitled to order a drink in English and to be irritated when the waiter didn’t understand. There was that other thing too from the meeting held in Pryce’s cubicle in the embassy where he’d summoned Mueller and then made him wait half an hour. That had put Mueller in a foul mood, and none of the smiling, pretend friendliness Pryce later exhibited got Mueller to recover his goodwill. He listened to Pryce’s summary of the state of play in Cuba. Castro’s forces had turned back Batista’s summer offensive in the Sierra Maestra mountains so now the chaotic opposition forces had no choice but to follow the lead of Castro’s July 26th Movement. The name, he said, when Mueller asked, commemorated the date Castro attacked Moncada Barracks in 1953. Not much was accomplished after his brisk report. A goal agreed, the rules of the game set – when and how to communicate, each keeping the other informed of what he did. Easy promises of cooperation.

Pryce nodded at the tall, cold drink that landed on the table. ‘Papa Doble. House specialty. Hemingway sits over there in the corner and orders three at a time. One puts the ordinary drinker in a blissful state, but he does three. Immense daiquiris with grapefruit juice instead of lime. Sailors approach him having read his books on a long ocean voyage hoping to shake the hand of the man who won the Nobel Prize.’

Mueller shook his head when he was offered a taste.

‘I read your novel,’ Pryce said. ‘What’s it called? Judas Hour? Not even the tradecraft was believable. Poison toothpaste? It made me wonder if you’d ever worked in the field.’

Mueller felt his cheeks flush. The incident Pryce brought up only to disparage was from the beginning of the novel when the main character is dispatched on a mission to assassinate a popularly elected African president. Mueller had struggled to fill the lacunae when a stubborn Agency censor deleted a classified killing technique.

‘The false detail spoiled the rest of the book.’ Pryce affected preoccupation with his cigarette, holding it before him, studying it, then again put it between clenched teeth. Mueller watched him finish the entire cigarette without removing it, ash lengthening, drooping, falling in clumps on his cotton shirt as he spoke. Sometimes he brushed away the ashes, but he continued to offer his literary critique with the cigarette dangling from his lips. When he accused Mueller of being inauthentic he snatched the cigarette with his fingers so he could apply the full force of his speech.

‘I expected something better from you.’ Pryce set his drink down carefully on the coaster, centering it, then slowly raised his eyes. ‘I followed you here, you know.’

Mueller raised his eyes. ‘Oh.’

‘I was across the street. I saw someone leave the portico and run with a newspaper over his head. Then I saw it was you. I lowered my car window and yelled, but you didn’t hear me. I wondered what was so urgent that you’d leave a dry spot. I thought, hell, he’s got his interview with Hemingway.’

Mueller remembered what Lockwood had said. He’s a homesick man trying to keep busy. He felt the conversation lengthening. ‘Nothing better to do? No crooks to shake down?’

‘No shortage of things for me to do, George. Plenty to keep me busy. The mob. You guys keep me busy.’ He paused. ‘Toby Graham keeps me busy. He’s stationed mid-island but I hear he’s in Havana now. Have you caught up with him?’

Mueller was silent.

‘Remarkable man. Dangerous man. Hard to pin down what he does, but by what people say of him, all the things, he could be two men. One person couldn’t do all of it. Men like him are put in the field and expected to use their judgment. It’s their willingness to push the edge of things that makes them good. Has he crossed the line? There’s talk he’s a hit man.’

The words made the nerves on the back of Mueller’s neck constrict. They were rarely seen in Agency memoranda, and if used at all, it was done allusively. No one wanted to acknowledge or admit to state murder. The director had not suggested it. Lockwood raised doubt without passing judgment by using the anodyne: Our options are limited.

‘Sounds like you know what you need to know.’ Mueller felt himself being tested. Mueller looked directly at Pryce. ‘I’m not sure what I’m doing here. Maybe I should take the next flight home.’

Pryce exhaled from the corner of his mouth. He affected pleasantness. ‘You guys in the CIA are a smug Ivy League bunch.’

‘I’m not one of them,’ Mueller said coldly. ‘I don’t have a stake in this. You want my help? Happy to help. Happy to let you figure it out by yourself too. But don’t mistake why I’m here. Or who I am.’

Mueller looked at his watch again and made no effort to hide his impatience. ‘I think we’re done here.’

Pryce stared. He looked around the bar and his eyes settled back on Mueller. ‘You’re meeting him. Is that what’s going on?’

‘He asked to see me. Alone.’

Pryce stood. He hitched his belt over his lumpish gut and thrust his shoulders back like a displaying turkey. He looked at Mueller, then glanced around the bar again. ‘You don’t know half the trouble he is in.’

On the radio, a Mexican song with bright brassy instrumentation and whoops and whistles had just ended. There came a sad song of plucked and strummed instruments accompanied by tenors singing melancholy lyrics with the refrain, Mama son de la loma. The bartender reached over to the radio and raised the volume.

Suddenly a Cuban among the seated group leapt to his feet. He was a slight man in a baggy suit, young, gentlemanly, a bit reserved, with a trimmed moustache and beaked nose. He had sprung from his seat like a jack-in-the-box. His wiry frame was board stiff, his voice strident, and he yelled toward the sailors, ‘Abajo el tirano. Abajo el dictador.’

‘Now there will be trouble,’ Pryce said laconically. He dropped his cigarette to the floor and ground it with his heel.

Startled customers became alert. The American couple looked up from their Havana guide book. Other Cubans at the table rose from their chairs, and added a loud chorus of Abajo el dictador.

A burly waiter hustled the Cuban provocateur out of the bar. Waiters moved among the tables solicitous, chagrined, apologizing. ‘He was referring to Franco, of course.’

Suddenly, a detonation rattled the quiet of the afternoon. A brilliant fiery flash went off outside the bar. It was followed instantly by a massive concussive blast that blew out the bar’s plate glass window and left the floor littered with broken red and white wine bottles so the floor was the color of rose. A hint of alcohol in the air mixed with the sweet sulfur odor of explosives.

A profound quiet settled around Mueller. Anguished faces of the injured in the room were mute. And then the knobs inside his head that control hearing turned up and everywhere he heard desperate pleas for help.

Pryce touched his shoulder. ‘You okay?’

Mueller realized he was sitting on the floor and he had no memory of how he’d gotten there. He cupped his ears and gently rocked his head to silence the ringing. He was surprised not to find blood.

‘Don’t go out,’ Pryce said. ‘They time the second bomb to follow the first.’

Waiters had gathered at the smashed window and cautiously looked beyond the jagged glass that formed the hole. The American held his wife’s hand, which bled profusely where a projectile of flying glass had neatly sliced through the wrist so it now hung by a tendon.

Mueller rose and made for the door, to escape, or observe, he wasn’t sure.

‘Stay put,’ Pryce shouted. ‘No one should go out until the police have cleaned the street. You can’t be of any help. The country has to burn a little before it gets its sense back.’

Mueller saw Pryce use his belt as a tourniquet on the woman’s arm and settle the numbed husband with a few calming instructions. Mueller paused, surprised by Pryce’s gesture, and seeing that side of the man made Pryce more human – more dangerous.

Mueller stepped outside. Already it was chaotic in the street. The grim tableau of violence was softened by the steaming vapor of the drenching rain rising off the hot asphalt. A milk truck had been reduced to its axle and the rest of the vehicle was gone, vaporized. Radiating from the mangled chassis were crates, broken bottles, and pooled milk thinned by the rain. Overturned cars formed a perimeter around the blast zone.

Mueller walked in the soaking rain among the injured. The face of terror was always the same. Injured bystanders sat stunned on the sidewalk, and he moved from one to the next with his offer of help. The dead were obvious. Body parts were scattered about, as if left by a tide – a naked leg severed at the hip still with its high heel shoe. A pregnant woman with a gash on her cheek. Her dress had lost a strap and one breast hung free. Mueller covered her shoulders with his sport jacket.

Pouring rain blurred the edges of violence and only approaching sirens brought Mueller back to the moment.

Police arrived first, and within minutes the ambulances, and then shortly afterward the green Oldsmobiles of the Servicio de Inteligencia Militar. SIM officers went about cordoning off the blast site with a perimeter to hold back the crowd gathering under the portico. They wielded cudgels against bystanders who ventured too close to the smoldering debris. From time to time one of these men in tan uniforms culled a bystander and dragged him to a paddy wagon. Pale blue uniforms of the regular police inspired respect from the crowd, but the tan uniforms of SIM inspired fear. One or two young boys knew what to expect and backed away. The crowd knew how to react to the threat. Everywhere cautious people hung back.

Mueller saw a young girl barely to puberty grabbed by a SIM officer. Her sly retreat toward a side alley indicted her. The thuggish officer struck once on her back with the sound of a crack. Her face curled in pain. She wore sandals, a loose dress, and long hair that he pulled. Mueller thought she was his son’s age.

He saw the officer strike again. She was too small, too frail, too childlike to resist. The sight stirred him from his complacency. He turned away from the girl, but her screams continued. Mueller cursed the impulse that rose in him. He had trained to be indifferent, to be cautious, to inure himself to the terrible things in the world.

‘Enough,’ he said. He stood tall, dignified, a surprising authority over the stocky officer. ‘She is a girl. Una joven.’

The officer, startled at the intervention, paused to take the measure of the man challenging him.

‘She did nothing,’ Mueller said, seeing he had the officer’s attention.

The officer gave Mueller a blasphemous look that said he could do what he wanted to the girl. She had already hunched over against the coming blow. Mueller grabbed the officer’s forearm and stopped his swing from landing.

He was promptly arrested. Tan-uniformed SIM surrounded Mueller and handcuffed him. He tried to be calm as he was dragged to the paddy wagon and placed among other handcuffed men. Mueller saw the girl lying on the sidewalk like a broken doll. He also saw Frank Pryce, who’d seen the whole episode from the bar. He stood in the doorway, arms akimbo. His face had a flat expression that revealed the burden of his contempt.

Gray light in the paddy wagon was extinguished when the double doors were slammed shut. Faces of men inside were illuminated only with the cab’s peephole. The closeness of their bodies, dank with sweat and rain, made the men less human. Faces around Mueller were grim, eyes wide, fear palpable. The man across from Mueller had the toughened expression of a prisoner rallying courage against coming indignities. Mueller saw he was the same man who’d jumped from his seat like a jack-in-the-box.

Mueller knew there was nothing to do but allow himself to go through with the arrest. Press credentials in his pocket would provide some measure of protection.

Mueller recalled Pryce’s comment that the country had to burn a little. It was the sort of thing Toby Graham would say, to justify the violence. Graham had always been one of those men whose dedication to work took him into the darkness, and as a matter of course, doing the work he did, he brought some measure of darkness into himself. How do you keep the darkness from consuming your humanity? Mueller had seen it, he’d feared it, avoided it, and he recognized it. There were rumors about Graham. Terrible things he’d organized, administered, deployed, carried out in Guatemala. Did he have a hand in this?

3

HOTEL NACIONAL

‘She was a dopey blonde.’

Mueller sat on a sofa in the Hotel Nacional’s vast marble lobby with an espresso that he sipped parsimoniously to play out the little drink for his conversation with the woman at his side, who flipped photographs of her portfolio and accompanied each with a remark. He leaned forward to get a better look at the bikini model at the wheel of the pink Cadillac convertible. He tried his best to be impressed.