7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

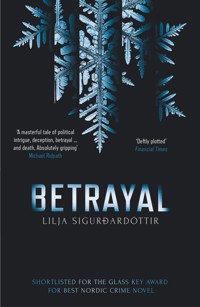

A stunning standalone thriller from the Queen of Iceland Noir. ***Shortlisted for the Glass Key Award for Best Nordic Crime Novel*** 'Tough, uncompromising and unsettling' Val McDermid When aid worker Úrsula returns to Iceland for a new job, she's drawn into the dangerous worlds of politics, corruption and misogyny … a powerful, relevant, fast-paced standalone thriller. ____________________ Burned out and traumatised by her horrifying experiences around the world, aid worker Úrsula has returned to Iceland. Unable to settle, she accepts a high-profile government role in which she hopes to make a difference again. But on her first day in the post, Úrsula promises to help a mother seeking justice for her daughter, who had been raped by a policeman, and life in high office soon becomes much more harrowing than Úrsula could ever have imagined. A homeless man is stalking her – but is he hounding her, or warning her of some danger? And why has the death of her father in police custody so many years earlier reared its head again? As Úrsula is drawn into dirty politics, facing increasingly deadly threats, the lives of her stalker, her bodyguard and even a witch-like cleaning lady intertwine. Small betrayals become large ones, and the stakes are raised ever higher… ____________________ Praise for Lilja Sigurdardóttir 'Tense and pacey' Guardian 'Highly unusual' The Times 'Smart writing with a strongly beating heart' Big Issue 'Deftly plotted' Financial Times 'Breathtakingly original' New York Journal of Books 'Taut, gritty and thoroughly absorbing' Booklist 'A stunning addition to the icy-cold crime genre' Foreword Reviews

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 452

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

i

Burned out and traumatised by her horrifying experiences around the world, aid worker Úrsúla has returned to Iceland. Unable to settle, she accepts a high-profile government role in which she hopes to make a difference again.

But on her first day in the post, Úrsúla promises to help a mother seeking justice for her daughter, who had been raped by a policeman, and life in high office soon becomes much more harrowing than Úrsúla could ever have imagined. A homeless man is stalking her – but is he hounding her, or warning her of some danger? And why has the death of her father in police custody so many years earlier reared its head again?

As Úrsúla is drawn into dirty politics, facing increasingly deadly threats, the lives of her stalker, her bodyguard and even a witch-like cleaning lady intertwine. Small betrayals become large ones, and the stakes are raised ever higher…

Exploring the harsh worlds of politics, police corruption and misogyny, Betrayal is a relevant, powerful, fast-paced thriller that feels just a little bit too real…

Betrayal

Lilja Sigurðardóttir

Translated by Quentin Bates

CONTENTS

PRONUNCIATION GUIDE

Icelandic has a couple of letters that don’t exist in other European languages and which are not always easy to replicate. The letter ð is generally replaced with a d in English, but we have decided to use the Icelandic letter to remain closer to the original names. Its sound is closest to the hard th in English, as found in thus and bathe.

The letter r is generally rolled hard with the tongue against the roof of the mouth.

In pronouncing Icelandic personal and place names, the emphasis is placed on the first syllable.

Úrsúla – Oors-oola

Óðinn – Oe-thinn

Rúnar – Roo-nar

Gunnar – Gunn-nar

Kátur – Kow-tuur

Eva – Ey-va

Gréta – Grye-ta

Freyja – Frey-ya

Herdís – Her-dees

Ingimar Magnússon – Ingi-mar Mag-noos-son

Thorbjörn – Thor-byortn

Katrín Eva – Kat-reen Ey-va

Jónatan – Yo-natan

Pétur – Pye-tuur

Guðmundur – Guth-mund-uur viii

With the benefit of hindsight, it was clear that Úrsúla’s promise, made on her very first day in office, was her downfall. At the same time it cracked open the armour that had encased her heart for far too long.

The night after accepting the keys in front of the press, she had dreamed terrible things. Her dreams were of fevered bodies, open sores, despair in the eyes of those bringing sick relatives to the camps, and then explosion after explosion, as if her former roles in Liberia and Syria had merged into one seamless nightmare.

The next morning she was still dazed and exhilarated after the previous evening’s reception at the ministry, and the cards bearing messages of goodwill and the flowers that had been presented to her were still piled high in her office. But the dream had left her feeling raw, so she was ill-prepared for the heartfelt rage of the woman who sat opposite her, begging her to help bring to justice the police officer who had raped her fifteen-year-old daughter back home in Selfoss.

The girl had hardly spoken a word since, didn’t want to leave the house. She had lost herself completely, the woman said as the tears flowed down her face. She wiped them away, whimpering with frustrated fury, and asked where the case had got to. She had asked the police, the state prosecutor’s office and her lawyer, but nobody seemed to know anything. So Úrsúla made a promise. She promised to make it her business to find out. She took the woman’s hand, who clasped it in her own, looked into Úrsúla’s eyes and thanked God that the minister of the interior was a woman.2

Friday

1

He was still full after the hot porridge at the Community Aid canteen, and the snow was deep, reaching halfway up his calves, so he ambled rather than walked. The snow was still coming down hard, so he decided to shorten his usual walk today. He wouldn’t go all the way down to Kvos as coming back again would be heavy going.

He started at Hlemmur, always at Hlemmur. There was a kind lady there at the bakery who always pushed a pastry his way. He’d usually keep it in his pocket so he had something for later on, when he’d feel the need of it. Sometimes he was hungry and would eat it the same day, and at other times he’d save it and have it a day or two later. Danish pastries kept well. Normally they were just as good after a couple of days. He left this time with both a twisted doughnut and some kind of fancy, nutty pastry in his pocket. It was a comfort to know that he had something to fall back on, in case he couldn’t make it to the Community Aid canteen but was still hungry, just like that summer when he had broken his leg. He had been properly in the shit then, living on his own in the bushes up at Öskjuhlíð, unable to walk and find himself anything to eat. It would have been great to have had something in his pocket then.

The next place was the kiosk. Sometimes he’d get coffee there, and sometimes small change, depending on who was behind the counter.

‘Good day, and may it bring you joy,’ he said as he pushed open the door. The cheerful response to his greeting told him that today 4there would be a handful of coins, so he may well be going all the way to Kvos, where he could visit the booze shop and buy beer.

‘G’day, old fella,’ said the pleasant young man who was there a couple of days a week. ‘What do gentlemen of the road have to say today?’

‘It’s snowing,’ he replied.

‘Proper snow,’ the lad added.

‘A proper winter,’ he said, and winked roguishly. ‘Any chance you could slip me a few coins, my friend?’

There was a ker-ching as the boy opened the till and scooped a palmful of hundred-krónur coins from the drawer.

‘There you go, old fella,’ he said. ‘Go and get yourself a bite to eat.’

‘Yep, I sure will,’ he lied. ‘A burger.’ He could see from the young man’s expression that he didn’t believe him; not that it mattered. ‘What’s your name again, my friend?’

‘My name’s Steinn,’ the boy laughed. ‘As I tell you every time you come in here.’

‘Names don’t matter,’ he mumbled on his way out. ‘Just eyes. The eyes tell you everything you need to know about someone.’

This Steinn had friendly eyes, with a spark of mischief behind them; the eyes of a man rebellious enough to steal from the shop’s cash register. But at the same time, friendly and charitable enough to give an old drunk small change. He strolled along Laugavegur, the snow settling on his head as he walked, forming a crown that melted until his thin hair was soaked and he began to shiver with the chill of it.

At the corner of Snorrabraut he crossed the street and went into one of the tourist shops; the thin, miserable man who worked there immediately threw him out. He tried to mutter that he only wanted to warm himself up a little, but that made no difference. The skinny guy was adamant that this wasn’t the place for him, and glared at him with his blank eyes, threatening to call the police. That would be something, being pulled by the law in a 5shop in the middle of the day, as sober as a judge and without even losing his temper. That would be a waste of a ride in a car and an overnight stay, so he left and walked briskly down to Kjörgarður – the heating under the pavement along this part of the street was easily enough to melt the falling snow – and before he knew it he was indoors with a mug in his hands. He hadn’t even needed to spend any of his stash of coins; the Asian lady who sold noodles there just handed him a mug and told him to sit down. She was loud and he didn’t understand a word of what she said, but she had kind eyes. He could see in them that she missed her parents, in a distant land far away, so she was happy to do a favour for an old guy with no home to go to.

He sipped his coffee, which gave him a glow of warmth inside, and leafed through the newspaper on the table in front of him. On the first spread, there she was, Úrsúla Aradóttir, with the news that she had become a minister. Somehow it didn’t seem quite right that she could be as grown up as she appeared in the picture, but there was no doubt that it was her. Once again he had the odd feeling he sometimes got – that the lives of other people moved ahead along straight lines while his own time went in circles. He took out his notebook and was about to write down these thoughts when his eyes strayed to the man at Úrsúla’s side in the photograph. They both smiled as they looked at the camera. But while her eyes were lively and cheerful, as they always had been, his were as cold as ice. These were the coldest eyes in the whole world. He stared at the picture and failed to understand how Úrsúla, now a minister, and whatever else she might be, could stand there and shake the hand of this man, the devil incarnate.

2

They had just left the marriage guidance counsellor’s office that Monday when Úrsúla’s phone had rung and the prime minister 6gave her two hours to make up her mind about taking on the role of interior minister for a year, a post combining the Ministries of Justice and Transport. Her eyes were still red with tears after yelling at Nonni in front of the counsellor, and she was sure her voice betrayed her upset as she told the PM that she would call back before the deadline. But she didn’t really need two hours, and she didn’t need to discuss it with Nonni before reaching her decision. She knew that she would make the call in good time and that she would take the job.

Nonni became weirdly excited and dropped his voice almost to a whisper, as if he was now party to some kind of state secret. His hand cupped Úrsúla’s elbow, steering her towards a coffee house on Skeifan, where he took her to a corner table by the window.

‘So just what did the PM say?’ he whispered, taking a seat opposite her.

‘Well, that it’s for one year, because the current minister has to step down for health reasons.’

‘Wow.’

‘It’s a bit awkward,’ Úrsúla said. ‘Appointing a minister from outside parliament and from neither of the two parties means they haven’t been able to agree on which of them should get the ministry.’

‘It’s a smart move to take a third option,’ Nonni said, falling silent as the waitress appeared.

Úrsúla had ordered a coffee, but Nonni had asked for a beer, which was unusual for him in the middle of the day. He had to be more upset than he appeared.

‘You’ll do it,’ he said. ‘Maybe it’s exactly what you need; what you need to be able to put down roots here again. Maybe this is something that’s exciting enough for you.’

Úrsúla nodded and they sat in silence for a while. Nonni took a long swallow of beer, which emptied half his glass.

He was probably right. She hadn’t been happy since they had 7come home; she felt out of touch – in a daze while life passed her by. This wasn’t the way she had foreseen things unfolding. She had expected to spend her whole life in charity work, somewhere sandy and hot, where the burning heat on her body would show her that she was making a difference.

‘What about the children?’ Úrsúla asked, although she didn’t expect anything would change for them, whether she became a minister or not. Nonni had looked after them mostly and would continue to do so.

‘I’m only teaching part-time and I can arrange my hours so I can do more preparation at home, so this isn’t a bad time.’

‘I should be able to help people out there,’ Úrsúla said and looked absently out of the window. It was snowing again, and a fresh layer of white was covering the grey that already lay on the ground. That was what she desperately wanted: to make a difference. To turn chaos into order, to make a difference to someone’s life, somewhere. Nonni reached across the table and laid a hand on hers.

‘It’ll be good for us as well,’ he said quietly, looking into her eyes. The argument in the counsellor’s office just now was already forgotten and the sparkle of humour had returned to his gaze. ‘A happy Úrsúla means happy kids and a happy Nonni.’

‘You’re sure about that?’ she asked. She wanted to hear his words of encouragement said out loud, to hear him speak his mind, to voice his decision to support her. She wanted to be reassured that things wouldn’t go back to the way they had been, with him criticising her decision to take on a demanding role, feeling sorry for himself for getting too little of her attention, turning his back on her.

‘Quite sure,’ he said. ‘It’s no coincidence that an opportunity like this should pop up right now. This is supposed to happen. I’m a hundred per cent behind you, my love.’

Úrsúla squeezed his hand in return. It was a relief to hear his unequivocal support, although it didn’t affect her decision. She 8had already made up her mind. She had done that before the conversation with the PM had ended. This was what she had been waiting for, something that sparked a desire inside her. This would be something that would wrench her out of the daze she had been in since she had left Liberia, on her way to the refugee camps in Syria.

3

The meeting with Óðinn, the permanent secretary, was a relief after the stiff formality of that morning’s State Council session. She had struggled to sit still while one minister after another had got to his feet to list his achievements in parliament to the president, who had been surprisingly successful in feigning a real interest in these long lists. Úrsúla had been badly nicotine starved and puffed the smoke of two cigarettes out of the car window as she hurtled back to the ministry to meet Óðinn.

He was impeccably turned out, a waistcoat buttoned under his jacket and his tie neatly knotted at his throat. As soon as the doors closed behind them, he shrugged off the jacket and hung it on the back of a chair; Úrsúla allowed herself to relax too, kicking off her heels beneath the table and drawing her feet under her chair. Óðinn started by passing her a little bottle of hand sanitiser.

‘Make sure you use it all the time,’ he said. ‘Over the next month you’ll have to shake more hands than you’ve shaken in your whole life so far, and the flu season’s almost on us.’

She laughed, squirted it into one palm and handed it back to him. Then they sat each side of the conference table and kneaded the gel into their hands. The sweet menthol aroma from her palms reminded Úrsúla of how safe she was now. There was no infection here that an ordinary sanitiser couldn’t cope with. In Liberia they had washed their hands in bleach.

He took care to work the gel in between his fingers. His hands 9were large, as was his whole frame. He had to be at least one metre ninety, and with a barrel of a chest, although he was slim with it, which indicated either manual labour in the past, or that he had been a sportsman. Once he had finished rubbing the sanitiser into his hands, he waved them a few times to dry them off. Úrsúla wanted to laugh – he resembled a giant, clumsy bird – but she held back.

‘Being ill isn’t an option, unless you are in hospital with a burst appendix,’ he said.

She nodded. He was making such a point of this, she wondered if he had bad experiences with ministers who were susceptible to infections. Rúnar, her predecessor, had stood down from the post for health reasons, but she assumed that was a heart problem or something equally serious.

‘Do you have high stomach-acid levels?’ Óðinn asked, his expression so serious that she couldn’t stop herself laughing.

‘No. Why do you ask?’

‘That’s good. In that case I advise you to eat plenty of chilli with every meal to keep stomach infections at bay. A minister with bad guts is nothing but trouble.’

‘Got you,’ she agreed. ‘I’ll do everything I can to stay healthy. But isn’t it time we took a look at the list?’

She pointed to a page of closely typed text on the table between them, listing all the matters they needed to attend to. Óðinn nodded, sat up straight in his chair and started at the top of the list: protocols for a non-governmental minister’s relations with parliament.

She nodded her head and listened absently, examining his face. He had to be close to sixty, with grey in his hair and a network of fine lines around his eyes that suggested that he frequently smiled. His current formal manner had to be because bringing a new minister up to speed with the job was a serious matter.

‘Then there are your assistants and their areas of work. Sometimes there’s a political adviser and a personal assistant, but if 10they’re the same person then it makes financial planning easier. Do you have any names in mind?’

‘I haven’t had time to think it over properly, but there are people from both parties who have made suggestions. I think one person will be enough,’ she said.

It was quite true. There had hardly been time to draw breath since the prime minister’s call on Monday giving her a two-hour deadline to decide whether or not to take the job.

‘Then there’s the car and the driver…’

‘No, thanks,’ she said, and Óðinn looked up in astonishment.

‘What do you mean?’

‘I can drive myself,’ she said. She had strong opinions about ministerial cars. Of course there was a certain convenience about such an arrangement, and it saved time. But there was something a little too grand about being driven in a smart limousine among normal Icelanders who were paying for it. It was simply not her style.

Óðinn put the list aside and leaned back in his chair with a thoughtful look on his face.

‘You realise that the only thing people miss once they’re no longer a minister is the driver? You can deal with emails on the way to and from work, you can send him to run errands for you, and he’s also responsible for your security. He’ll shovel snow off the steps, change lightbulbs, all that stuff.’

‘I’m married, you know,’ she said, and at last Óðinn cracked a smile.

‘We can discuss this later,’ he said, and although she had not meant to leave it open to further discussion, she nodded her agreement so they could continue with the list. She was desperate for a cigarette and wanted to get the meeting over with.

All the same, a full hour had passed and Úrsúla was edgy from nicotine withdrawal by the time Óðinn crossed off the final item on the list and got to his feet. She felt him loom over her as he offered his hand. 11

‘Welcome to the job,’ he said. ‘I’m here for you all the time, for anything, and I speak for the whole ministry when I say that we will do everything we can to ensure your tenure here is successful.’

She stood up and gripped his warm hand.

‘Thank you very much,’ she said. She had a feeling inside that they would work well together. He smiled and she saw the lines around his eyes deepen. For a second he reminded her of her father; not as he had been towards the end, but as she remembered him when she had been small and they had played together.

‘One more thing,’ she called after him as he was about to leave the conference room. ‘There was a woman who called here this morning with a request for the ministry to look into a case. It’s a rape accusation that seems to have been held up in the system. My secretary booked it as a formal request. Would you look into it and give me some advice on how to proceed?’

‘Of course,’ he said from the doorway. ‘I’ll check on it.’

Úrsúla accompanied him along the corridor towards her office, and as she was fumbling for her access card to open the minister’s corridor, she noticed a very young dark-skinned woman pushing a cleaning trolley.

‘Hæ,’ Úrsúla said, putting out a hand. ‘I’m the new minister. I don’t suppose you can tell me where someone could sneak out for a quiet smoke?’

4

There had been a strange crackle of tension in the air the whole of the previous day, and Stella was still feeling its effects. Everyone went about their work more quietly than usual, and there had been more couriers and journalists about the place than usual.

The receptionist downstairs had asked Stella to mop the lobby especially thoroughly because of the snow that was brought in on coats and the soles of shoes, and melted into muddy pools on the 12floor. She did her best, making the occasional quick sortie downstairs with a mop to wipe up the worst of the water. She didn’t want to be caught out not doing as she had been asked, as that would undoubtedly end up with the permanent secretary being called, as he seemed to be the top dog here. Stella found him frightening. She had encountered him once, when he had said hello, welcoming her to the ministry when she had started a few months ago. He had smiled amiably, but Stella had wanted to turn on her heel and run as fast as she could, as the touch of his hot hand gave her a feeling of pure, clear misery. This had taken her by surprise, as he seemed to be a man to whom life had been generous – tall, handsome with a senior job – so the dark sadness she sensed from him didn’t fit. Or maybe this sensitivity of hers was playing tricks on her. Her mother had always said that the gift she had inherited from her grandmother had come with a generous portion of imagination.

‘It’s always like this when there’s a new minister,’ the receptionist said. ‘Everyone’s stressed and worried, and then it turns out that the new minister is always lovely. I saw her yesterday when she came to collect the key and she seemed relaxed and cheerful.’

Stella shrugged. She had hardly had anything to do with the former minister; she’d only ever seen him hurrying along the corridors with a phone clamped to his ear. He had never spoken to her, and neither would the new minister. The receptionist was different, as everyone said hello when they came in, but cleaners were as good as invisible.

‘Well, she’s here,’ she heard people say as she passed by, emptying the bins. ‘Have you seen her yet?’

The new minister was in the building and had started work, but nobody seemed to have caught sight of her. She would probably not address the ministry staff until tomorrow, but people were sure they would recognise her, as last night’s news covered the change of minister and there had been a short clip in which she was holding the key.

Some people seemed to know her from her background in 13student politics, and someone mentioned that she had worked with refugees in foreign countries, organising aid in disaster areas, or something like that. But Stella neither watched the news nor read newspapers, so she knew nothing about this woman; she’d never even heard her name before.

It wasn’t a bad place to work, but Stella realised that she wouldn’t be here for long. Her job was part of a temporary initiative for young people who had ‘come off the rails’, and social security paid half of their wages. Mopping the corridors of the city’s smartest buildings was supposed to be a way of getting people’s lives back on track. The ministry’s staff had accepted her; they were clearly accustomed to having people in the building doing things nobody quite understood. After the first week she seemed to blend into the daily routine and nobody paid her any attention anymore. She liked that. She also liked the fact that as long as she kept the lobby floor dry and emptied the bins on the third and fourth floors, nobody was aware that she was there, as long as she punched herself in and out morning and afternoon. At the end of the day a bunch of people appeared from some big cleaning contractor and cleaned the whole ministry, so what Stella did or didn’t do made little difference. It was the easiest job she had ever had, and she had plenty to compare it against: in her nineteen years she had been through any number of jobs.

Her phone buzzed and she put the mop aside.

Party at our place tonight! read the message from Anna.

She didn’t check to see which Anna it was from. It didn’t matter. They were a couple, both called Anna. They were known as the Annas and threw regular lavish parties to which they invited only ‘cute, exciting’ girls. Stella knew that the colour of her skin alone put her in the right category; it was as if her golden-brown colouring worked like a magnet for lots of women. Normally she was quite happy to benefit from one of the few advantages of being one of the tiny minority of brown Icelanders. But after the last party the two Annas had thrown it had taken her a week to 14recover, and she had promised herself never to go back. But now it was Friday, and she was skint, with nothing to do but stay in her room and watch Netflix on the computer, so it didn’t seem such a bad idea. What else were weekends for if not having a little fun?

I’m busy and will be late, if I can get there at all, she wrote back. It didn’t do any harm to pretend that she actually had a social life; it added to her mystery. And anyway, she preferred to turn up late, when things were already in full swing and everyone had knocked back a few drinks. That way she wouldn’t have to hold any conversations. She always felt that she was more in control that way, although she knew deep down that once she had put away some of what was on offer she was as good as out of control. That was even without the Annas passing around the smarties.

She ran her fingers over the new Helm of Awe tattooed on her forearm, hoping it would protect her from drinking herself into a stupor and going home with someone she really didn’t want; such as the news reporter the Annas always invited and who was clearly in the ‘exciting’ class – courtesy of her TV fame, as she certainly wasn’t cute. Stella harboured a suspicion that the Annas were trying to pair her up with this woman, but her enthusiasm for this was precisely zero. Pondering this, she pushed the cleaning trolley ahead of her along the corridor and practically ran into a woman. The woman took hold of the trolley and stopped it with a laugh.

She extended a hand.

‘I’m the new minister,’ the woman said, and dropped her voice to a whisper. ‘I don’t suppose you can tell me where someone could sneak out for a quiet smoke?’

The speech that Permanent Secretary Óðinn had made earlier that day, emphasising that staff, whatever their political persuasion, were here to assist the minister in shouldering a great responsibility, came to Stella’s mind. So she took the minister to the fourth floor balcony, where she herself went to smoke. The minister could hardly be expected to shoulder all that responsibility without an occasional puff. 15

5

Gunnar put everything he had into that last lift. His shoulders screamed in pain and he was sure he could feel the tendons in his forearms tear under the strain. He was up to 150 kilos on the bench and while the fourth lift had been tough, the fifth was a bastard. He wasn’t concerned about the weights dropping onto him, though, and he couldn’t be bothered to ask a member of staff to watch over him, just in case things went badly. He was the competent, reliable type who fixed things alone when push came to shove. All his adult life had gone into preparing for this role, and he knew deep inside that a day of reckoning would come when the difference between life and death would be down to him alone.

‘That’s some proper punishment!’ said a man who walked past, and Gunnar realised that a loud gasp must have accompanied the last lift. He had to take a couple of deep breaths before he dared sit up. The sweat had glued his back to the bench and there were black dots dancing before his eyes. He was satisfied with what he had achieved, and now he needed to eat well to feed his freshly trained muscles. He wished they were even bigger, but for his work, not through vanity. His job called for bulging muscles, although bulk alone wasn’t the key; strength and courage had to go hand in hand.

He spent a long time under the shower, enjoying the feeling of his pores opening as the sweat washed away. Weightlifting was accompanied by a kind of spiritual wellbeing: the triumph of his will over his body never failed to make him proud of himself. It was more difficult with running though. He always had to force himself to run and generally didn’t feel great afterwards. But it was also important for work that he could sprint, not that he would often have to do it. He pulled on his trousers and decided to do without a singlet under his shirt. He was so hot that he felt as if he was on fire. 16

He quickly pushed his stuff into his training bag, put on his shirt and buttoned it up, but dropped his tie into a pocket. He could put it on in the car. He picked up his shoes, and walked barefoot to the gym’s lobby and out into the snow. To begin with the cold was pure pain, but this was followed by a chilled mist of satisfaction. The snow was soft, forcing itself up between his toes, and creaked with each step. By the time he reached the car his feet were numb, but the fire in his body had subsided and he felt good. Now his shirt wouldn’t be soaked with sweat. He turned up the car’s heater, directing it into the footwell to dry his feet while he knotted his tie. He’d put on his socks and shoes but hadn’t tied the laces when his phone rang. As soon as he saw the number he checked his watch in a moment’s panic, but there was nothing to worry about. He had a clear hour before he needed to be at the ministry.

Disappointment welled up in his chest as he put the phone aside, and the feeling that Iceland wasn’t the right place for him returned yet again. All his bodyguard training – most recently a course in evasive driving – would probably never be of any real use to him in this little country. He had imagined that the government offices would be just the place for him, and indeed they had liked the look of him, especially after the national commissioner of police had said there should be a higher level of security around ministers. But there were very few jobs going and plenty of people after them. All he could look forward to now was the same as usual: security at the ministries. He swallowed his disappointment and swore to himself. What sort of minister didn’t want a driver?

6

His feet carved a path through the snow as he ambled up and down Ingólfsstræti, keeping an eye on people going in and out of the ministry. He had tried to go in, but the security guard sitting 17in front of a computer at the reception desk told him to stay outside. He went round the corner of the building and climbed the steps under the balcony on the Sölvhólsgata side, but that door was locked, so he continued to wander around the building, peering through windows in the hope of seeing her inside.

Every now and again he stopped to look at the picture he had torn from the paper. There was no doubt whatever that this was the man: the devil incarnate. And he was holding on to little Úrsúla’s hand. She was no longer a little girl with cropped hair but a grown woman in a smart jacket and her hair in a bun. What on earth had she been thinking, giving him her hand like that? Examining the scrap of newspaper, he tried to imagine what the look in her eye might mean, but the picture was too grainy for him to judge whether her expression was one of a little girl who had got lost somewhere along the line and joined hands with evil.

He stopped by the statue on the mound of Arnarhóll and gazed back along the street. It was late in the day and he had yet to see her emerge. Thinking it over, he had seen remarkably few people passing through the doors of the building. The same people who had gone inside earlier had now come out, on their way home he guessed, many of the lights had been turned off, and few staff were now to be seen. There had to be a rear entrance to the building. He hurried back along the street towards the ministry, past the entrance on Sölvhólsgata and into the car park at the back. That was it. Beyond the gate, between the hotel and the ministry building, he could see another entrance from the lower car park that couldn’t be easily seen from the street. This lower car park was closed, with one of those electric gates that opened when a driver pointed a finger at it, but it was open to pedestrians, so he limped down the steps and into the car park. The spaces by the fence were unmarked, but right next to the building was a disabled space marked with a blue sign, and next to them the spaces he was looking for: those reserved for the minister and the permanent secretary. 18

There were cars in both spaces. One was big and black – a sleek 4x4 with darkened windows; it was in the permanent secretary’s spot. The other was a pretty ordinary family car – a Toyota – and he knew immediately that this had to be Úrsúla’s. He didn’t even need to look at the sign in front of the car. The Toyota hadn’t been properly cleaned for a long time and the roof was caked with hardened snow, as were the boot and bonnet. That was typical of little Úrsúla, whose mind was always on something other than where she was right now.

He pulled the sleeve of his coat over his hand and wiped snow from the windscreen. Soon Úrsúla would drive home and would be relieved not to have to wipe the snow off first. He cleared all of the windows with care, and then took out his notebook, tore out a page and wrote a message to Úrsúla. Unfortunately it had begun to snow again, so if he were to put the note under one of the wipers, it would quickly become soaked and illegible. He tried the door handle and found that luck was on his side. The door opened, so he could place the message to Úrsúla on the seat, where she would find it as soon as she went to get in the car. He smiled. It was typical of the little scatterbrain to forget to lock her car.

7

Úrsúla was surprised at her own surprise: she was taken aback by just how much of a shock the note was. She was already kicking herself for having forgotten to lock the car. It hadn’t occurred to her that by parking in the spot marked Minister, she was telling everyone which vehicle was hers. Clearly every fruitcake in the country had an opinion on everything imaginable, and that seemed to include her appointment as minister of the interior.

The devil’s friend loses his soul and brings down evil, the note read, the last few words an almost illegible scrawl. It looked like someone had decided she had made friends with the devil himself. There was 19nothing unusual about politicians being lambasted for entering into coalitions with people someone was unhappy with, but as she was not linked to any party, she had somehow imagined that this kind of criticism wouldn’t come her way. All the same, people ought to be used to seeing political parties working together when the parliamentary term was so far advanced, and anyway she’d simply been called in to finish the work begun by Rúnar. She screwed the note into a ball and flicked it aside, and it was lost among the mess of paper, juice cartons and sweet wrappers that filled the footwell. She reminded herself that this weekend the car would need to be cleaned as the smell was becoming overpowering. She sighed and tried to relax, to let her racing heartbeat slow. She had been aware before taking the job that she wouldn’t be popular with everyone and that she’d get to hear about it. But the note in the car had still been upsetting. Somehow it was too close to home, too personal. In future she’d leave the car in the other car park with all the others.

As she parked outside her house, she wound the window shut – the smell in the car had forced her to drive home with it halfway open. There had to be half a sandwich turning green somewhere down there, or something in the junk in the back. She’d have to ask Nonni to clean the car. Judging by the emails waiting for her and the long jobs list, there wouldn’t be much opportunity to do it herself. This weekend would have to be spent getting herself up to speed on everything the ministry did.

‘Congratulations, my love!’ Nonni called out as she opened the front door. ‘You made it through day one!’

Kátur bounced towards her, his furry body twitching with delight at seeing her again, and as usual she dropped to her knees to greet him. She held his little head in both hands, kissed the top of his head and breathed in the smell of newly bathed dog. Nonni regularly gave him a bath and used shampoo on him, even though Úrsúla had warned that it wasn’t good for dogs.

‘Lovely to see you, Kátur,’ she whispered into his fur as his tail wagged furiously. There was no limit to how much she loved this 20little dog. He had kept her sane when she had moved back home, becoming the compass that showed her the way back to love. He had helped her put aside her weapons and lower the defences she had erected around herself somewhere between the Ebola epidemic in Liberia and the refugee camps in Syria.

The dog wriggled from her arms, ran halfway along the hall into the apartment, and then back to her. That was what he always did, scampering between her and the family, as if he were showing her the way home to them. This was guidance she certainly needed, as since moving back to Iceland she had felt at a distance from them, as if they were on the far side of some invisible barrier that she had been unable to break through.

She took a deep breath, taking in the warmth of the household, and for a moment she was gripped by a doubt that she had done the right thing by jumping into a ministerial role. There was no getting away from the fact that it would mean less time at home, less energy to devote to the children, less time for Nonni. There would be less time for her own emotional recovery. But it was only for a year, the twelve remaining months of the parliamentary term.

‘Pizza!’ the children chorused the moment she stepped into the kitchen. They were busy arranging toppings on pizza bases, and she could see Nonni was preparing a seafood pizza just for the two of them. There was an open bottle of white wine on the worktop, a glass had been poured for her, and the dining table was set with candles.

‘You’re a dream,’ she sighed, kissing the children’s heads and wrapping her arms around Nonni. He was warm to the touch, freshly shaved and sweet-smelling, and she felt her heart soften with gratitude, blended with doubt that she genuinely deserved such a perfect man. This was how it had been for more than a year. Every time she felt a surge of warmth and affection towards him, it was accompanied by an immediate surge of bad feeling. There was guilt, regret and self-loathing. Why couldn’t she simply love him as she had loved him before? 21

‘So how’s it looking?’ he whispered and handed her a glass of wine.

She sat on a barstool and sipped. She’d tell him tonight, when the children had taken themselves off to bed. She would tell him how the day had begun, how she had been prepared for the first interview of the day, expecting to be getting to grips with complex and demanding issues, only to be faced with such a painful and difficult personal case.

The face of the mother who had sat opposite her that morning, rigid with anger and sorrow, remained vividly in her mind. As she watched her own daughter arrange strips of pepper to form a pattern on a pizza, she felt a stab of pain in her heart: she was only two years younger than the girl who had been raped.

Saturday

8

The report was so powerful that Úrsúla couldn’t be sure if it was the sheer loudness of it or the wave of air pressure generated by the explosion that pushed her eardrums in, leaving them numb, so that she lay face down on the ground in absolute silence. In her peripheral vision she could see some movement in the distance, but it was difficult to tell through the cloud of dust, so she lay still in the sand that now seemed to fill her whole consciousness, revelling in the joy at being alive that swept through her. She wanted to stay there and make the most of this feeling for as long as she could, because before long she would have to get to her feet and face the fact that the bomb must have gone off very close to the camp, perhaps right inside it, and there would be casualties. She would feel guilt at being alive and from there it would be a short stop to the deadness inside that had plagued her ever since Liberia.

The silence in her head dissipated gradually and she could hear faint shouts and moans. She flexed her arms, ready to stand up. It was high time to get the people who had sought shelter in the refugee camps over the border into Jordan.

Úrsúla was woken by the hammering of her own heartbeat. She was on the sofa at home in Reykjavík. There was a cartoon playing on the TV that had no doubt been put on for the children, who had woken ridiculously early. With a deep sigh, for a moment she wished she could be back in Syria, to the second after the explosion, when she had sensed the life force surge through her veins and felt that there was some reason for her existence. That was 23when she felt that she had a purpose, even a calling. She carried with her a responsibility to get living people – those who were frightened, hurt and in need – to shelter.

Now she wasn’t sure whether she had been asleep or having a vivid daydream, as if her thoughts had sought out memories that might kick-start her dormant emotions, exercising and stretching them back into life. Kátur crawled on his belly off her feet, where he had been curled in a ball, and along the length of her body until his damp, cold nose lay at her throat and she could feel his breath on her cheek. It was as if the dog sensed her thoughts. The love he always had for her never failed to melt her heart. Her affection for him was bound up with certainty and comfort. If she could love this bundle of fur, then surely she still had the capacity to love her own offspring.

Úrsúla sat up and shook off her own self-indulgence. Kátur watched her, waiting for a signal. If she were to get up, he would greet her as if she had just come through the door, then run to the back door – his way of telling her that he wanted to be let outside to pee. She would stand in the doorway, taking lungfuls of cold Icelandic outdoor air before brewing coffee and getting herself ready for the day ahead. She needed to go through a whole stack of documents, bring herself up to speed with the rules and regulations that applied to foreigners, and work out a job list for the coming week. It was clear that not much of her time would be her own, so she needed to make good use of the hours she had.

9

His expectations had created his disappointment. If he hadn’t so clearly envisaged himself doing his dream job, then he wouldn’t be so frustrated now. Although Gunnar understood the principles of Buddhism and tried to devote himself to them through meditation and the solutions that this offered, he still struggled to come 24to terms with the train of thought that said it would be better for him to accept right away that the bowl was cracked – that his dream job had been lost and that his life was already over.

He sat with his legs crossed, hands limp in his lap, concentrating on inhaling and exhaling while thinking of nothing but the flow of air that he felt crossing his upper lip and entering his nostrils then slipping down into his lungs to feed his bloodstream with oxygen, before taking away the carbon dioxide and discarding it by the same route. Fragments of daydreams in which his strength and alertness protected someone important from evil found their way into his consciousness. He repeatedly had to decline these thoughts – banish them so that he could continue to concentrate on the flow of air entering and leaving his body.

Meditation always helped, even though he never managed to maintain it for more than five minutes, and he was much calmer now, as he stood up, than he had been when he sat down, in spite of the burning disappointment. In reality he was disgruntled. It was a relief that he felt no real anger though. Anger was what he feared most, as it would herald rage. But there was only disappointment. He had been looking forward to taking on this assignment, getting to know the car and the minister, relishing the prospect of taking this task seriously and doing it better than it had ever been done in Iceland.

The real pain lay in knowing that, regardless of all his dreams and wishes, he had everything needed to make him a first-class bodyguard. He understood the importance of the role, that it was crucial to create a feeling of security so that whoever he was looking after could do their work without fear. He also had insight. Insight, as his teacher on the personal protection course in America had said, was the most important part of the bodyguard’s armoury. Insight meant feeling rather than knowing, and sensing rather than seeing. The key to all this was being able to trust these instincts.

He lifted both hands high above his head and bent forward to 25stretch his back after sitting. As he straightened up he felt a spark of hope deep inside him. Ministers come and go. In a year there would be another election, and then there would undoubtedly be a new government that would want drivers, and he could also start to look around for opportunities overseas.

‘Where on earth is anyone supposed to sit in this apartment?’ Íris asked as she came through the bedroom door into the living room, wearing one of his old singlets and with her hair awry. ‘Not everyone can sit on the floor all the time like you do.’

He smiled and pointed at the sofa.

‘Then the floor’s better,’ she said. ‘That sofa’s not something anyone would want to sit on.’

She was right that the sofa was neither smart nor particularly comfortable, but it was an excellent example of how to let a little suffice. This was something Íris didn’t understand, and whenever she came over or stayed the night she always complained about how sparsely furnished the place was. He got to his feet and went over to the kitchen worktop, where she stood shaking a carton of some protein drink.

‘Good morning, pretty lady,’ he said, a hand in her dark hair as he kissed her.

‘Good morning, handsome man,’ she replied.

She was a delight when she was like this, and he felt the fluttering down in his belly that came when he hadn’t seen her for a while, or when she was sweet and loving; when she had herself under control.

10

Time seemed to stand still, and when Stella looked at the clock in the living room it was always seven, every time. She wasn’t sure if that was seven in the morning or the evening, though. She had been hanging on all night for everyone to make a move to somewhere 26 they could dance, but nothing was happening; some of them had even started to dance in the living room. All of a sudden she was sick of it all and wanted to leave, but she was unsure if this was because there were no fun girls there, or because of the newsreader, who was always at her heels, trying to get her to talk, or just staring.