7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

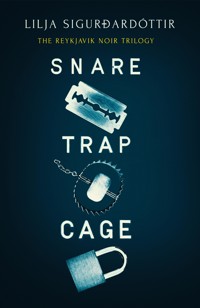

Drugs, smuggling, big money and political intrigue in Iceland rally with love, passion, murder and betrayal until the winner takes all … in the masterful, explosive conclusion to the award-winning Reykjavík Noir trilogy… ***Guardian Book of the Year*** ***WINNER of the Best Icelandic Crime Novel of the Year*** 'Tough, uncompromising and unsettling' Val McDermid 'One of the darkest and most compelling series in modern crime fiction … Tackling topical issues, the book will tell you a great deal about why the world's in the state it is, while never neglecting its duty to entertain' Sunday Express 'A tense thriller with a highly unusual plot and interesting characters' The Times _________________ The prison doors slam shut behind Agla, when her sentence ends, but her lover Sonja is not there to meet her. As a group of foreign businessmen tries to draw Agla into an ingenious fraud that stretches from Iceland around the world, Agla and her former nemesis, María find the stakes being raised at a terrifying speed. Ruthless drug baron Ingimar will stop at nothing to protect his empire, but he has no idea about the powder keg he is sitting on in his own home. At the same time, a deadly threat to Sonya and her family brings her from London back to Iceland, where she needs to settle scores with longstanding adversaries if she wants to stay alive… _________________ Praise for the Reykjavik Noir Trilogy: 'Cage is the muted and more credible conclusion to a wayward, but diverting trilogy that began with Snare (2017) and continued with Trap (2018) — ironic titles for essentially escapist fiction … Compassion beats complexity every time' The Times 'In keeping with a lot of Icelandic fiction, Cage is written in a clean, understated style, the author letting the reader put together the emotional beats and plot developments. Smart writing with a strongly beating heart' Big Issue 'Deftly plotted though and with a forensic attention to the technicalities of stock exchange manipulations and drug running techniques' Crime Time 'With shocks and surprises in store, and that oh so satisfying end, Cage provoked, chilled, and thrilled me' LoveReading 'A novel about survival, about scheming, it's about self-preservation and about clinging to a vestige of decency in a screwed up world. Superbly translated by Quentin Bates, who knows the language, the country, the people and crime writing intimately. Cage is a pacy thriller; you will find yourself invested in the story' New Books Magazine 'An emotional suspense rollercoaster on a par with The Firm, as desperate, resourceful, profoundly lovable characters scheme against impossible odds' Alexandra Sokoloff 'Clear your diary. As soon as you begin reading … you won't be able to stop until the final page' Michael Wood 'Zips along, with tension building and building … thoroughly recommend' James Oswald 'The intricate plot is breathtakingly original, with many twists and turns you never see coming. Thriller of the year' New York Journal of Books

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 411

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

iii

Cage

Lilja Sigurðardóttir

Translated by Quentin Bates

Contents

April 2017

1

The cell door shut behind Agla’s back with a smooth click. All the doors and walls in the new Hólmsheiði Prison were sound-insulated, so the women’s wing was quiet in the evenings. There was no slamming, and no calls or mutter of televisions carried through from the cells of the other women serving their sentences there. Instead there was a heavy silence, which seemed to engulf her like water – and she was sinking slowly and gently to the bottom.

She had known that being locked up wasn’t going to be a pleasant experience. A few years earlier she had been on remand for a couple of days while the market-manipulation case against her was being investigated, so she had been expecting something similar. But this was unlike anything she had anticipated. It was one thing to spend two or three days in a cell, at the end of which her lawyer had appeared like a guardian angel, sweeping her away to dinner; it was quite another to walk into this building that still smelled of damp cement and filler, knowing that it would be her world for the next year.

Now she had a month to go before she was eligible for parole. In her mind she had divided her sentence into sections: she had to complete half of her time and then the rest would be on probation. But now that the second section was within sight, she was consumed with trepidation. Somehow she had become the animal in the zoo that dared not leave its cage for fear of looking freedom in the eye.

As her time in prison had passed, she had found the cage an increasingly comfortable place to be; to the point where she was numbed by it. There was now something reassuring about having all her power taken 2away from her. The more she had complained about the hard mattress and the piss-warm shower, the more a simple fact had filtered through into her consciousness: whatever she did or said in here made no difference. Her own will was of no consequence.

She had the impression that life was progressing evermore slowly, and she was finding it increasingly difficult to make decisions. The warders would often suggest she played games or did some handiwork, or brought her books from the library; but she could no longer be bothered to play, work or read. The same seemed to apply to the other women. She’d seen those whose sentences had begun after hers turn up furious and bristling with pain, just as she had; but after three months all their fury had dried up, and now they hardly even spoke to each other.

Two of the Icelandic prisoners had arrived at the same time as Agla. With the justice system overloaded, like Agla and many others convicted of non-violent offences, they had had to wait a long time before they could start serving their sentences. Another woman had come here from a prison in the north, and one had joined them some time later. The foreign women were on the other corridor, so they had come and gone without Agla noticing. All of them had been mules – young women from Eastern Europe, dressed in track suits, with dyed hair and poor English. Like the Icelandic prisoners, they kept to their own corridor, but somehow their community seemed to be livelier, although the gales of laughter and the songs could sometimes turn into screams and fights.

At the beginning of her sentence, Agla had made daily visits to the fitness room, accepted interviews with the prison chaplain – if only to have someone to talk to – and made an effort when it was her turn to cook. Now, though, she no longer had the energy for any of this, and her fellow prisoners were lucky to get rice pudding and meat soup, as she couldn’t summon the energy to cook anything more demanding. Not that they complained; they had probably stopped tasting any flavour in the food long ago.

She took the nail clippers from her vanity bag, then used them 3to pick tiny holes in a sheet, so that she could tear it into strips. Two strips would definitely be needed, twisted together so they were strong enough. She had planned this a long time ago – when she had been informed that her probation was coming up, but she hadn’t made a decision about a precise day. Earlier, though, just after the evening news on TV, she had had the feeling that it was now time. Her decision was accompanied by neither sorrow nor fear, but instead by a kind of epiphany, as if a fog in her mind had lifted and for the first time in many months she could clearly see that this was the right thing to do.

It took longer than she had expected to rip up the sheet, and when she wound the two strips together, they lost half of their length, and became a short piece of rope. She looked around and immediately saw the solution, as if, now that the moment was near, new possibilities were appearing that she had not seen before. She unplugged the power cable for the TV and unwound it from its coil at the back of the set. It would work fine; it wouldn’t fail.

She made the sheet rope into a loop that would tighten around her neck, and then tied the loop to the cable. She got to her feet and went over to the radiator on the wall by the door. It was just about the only thing in her cell that anything could be tied to. Agla hoped it was high enough up the wall. She tied the cable to the top of the radiator and pulled at it – gingerly at first, afraid that the makeshift noose would give way, and then with all her strength. It seemed secure. She hoped that her body would not let her down at the last moment, responding with some self-preservation instinct and trying to keep her on her feet.

For a second the silence was broken by a blackbird’s song, as it made its nest somewhere nearby. The thick walls were not able to stifle the cheerful birdsong, and it triggered in Agla an immediate desire to step outside into the fresh air and inhale the scent of the blossoming birch trees. But this urge disappeared the second the birdsong came to an end, and images of her mother and Sonja passed through her mind.

The pain and the regret that came with these thoughts were so bitter, her heart ached; but at the same time she felt a sense of relief that this would be the very last time she would be tormented like this. Never 4again would she be outside these walls, having to stand alone, wondering why Sonja had abandoned her. Never again would she have to face the endless choices that freedom offered, and that, up to now, had mainly brought her misfortune. It came as a relief that her life was over.

She stood with her back to the radiator, pulled a plastic bag over her head and looped the noose about her neck. The moment she had tightened the noose, she sighed once, with satisfaction, and then sat down.

2

The chill evening breeze left Anton shivering. He zipped up his coat and checked the time on his phone. Eight minutes had passed since Gunnar had taken the moped they had brought to where they had decided to hide it. The only reason he had brought Gunnar in was because of his moped. At one point he had considered taking his dad’s car, because he could drive just fine, even if he was only fifteen and didn’t even have a provisional licence yet. But taking the car would have been risky – especially if they were pulled over by the police – and if anyone was about, a car would be more noticeable than a moped with no lights.

He heard quick footsteps approaching him from behind, and he spun around. It was Gunnar, running towards him with his white helmet on his head like a giant mushroom. They had agreed to wear helmets the whole time, both to reduce the likelihood of the police stopping them and so that any security cameras wouldn’t pick up images of their faces. Fortunately, though, there didn’t appear to be any cameras here. He had been checking the area out over the past few days, and knew that the roadworks guys used a diesel generator for the lights and heating in their shed. But now everything was dark – so dark that the green hue of the northern lights dancing in the eastern sky was unusually bright.

Anton shouldered the backpack containing their tools, and they hurried on quiet feet over to the fence, where Gunnar took the wire 5cutters from the bag and started making a hole big enough for them to crawl through.

‘That’s just a catflap,’ Anton said. ‘The hole has to be bigger. We need to get back through it with full backpacks.’

‘OK,’ Gunnar agreed, snipping a few more wires, but he was obviously tired already, so Anton took the cutters from his hand and continued the work. Even though these were decent cutters, brand new and sharp, the mesh was still unbelievably hard to cut. He had to use all his strength to break each strand.

To begin with they had planned to go over the fence, but the coils of razor wire at the top put an end to that idea – they would have had to cut through that anyway, so it was as well to forget climbing and make a hole down here. It was also safer, as there was less chance of them being seen at ground level.

‘Give it a pull now,’ Anton said.

Gunnar twisted the tongue of mesh upwards so that Anton could crawl through, then Gunnar followed behind him. They jogged past the workmen’s cabin to the storage shed behind it. Anton shook off his backpack, and they took out the head torches and fixed them to their helmets. He was pleased with this idea; they could see what they were doing without having to hold torches or a lamp.

‘OK,’ he said. ‘Let’s do it.’

Gunnar did not need to be told twice. He took out a hammer and began battering the padlock, while Anton set to work with a screwdriver, trying to unscrew the hinges. This was one aspect of the job they had not agreed on. They had spent time lying in the scrub, looking down on the place with a pair of binoculars, watching to see how the shed was closed and arguing about the best way to open it. It didn’t seem to be a proper door, more a homemade job with a sheet of plywood that had been cut to fit the opening and fixed with hinges on the outside. After racking their brains for a while, they decided on both approaches; they’d see which was the one that got them inside the shed first. Anton knew that the method didn’t matter. It was the objective that was important. But Gunnar seemed to think there was a principle 6at stake, and insisted on smashing open the padlock, so Anton had accepted this compromise.

‘There!’ Gunnar whooped as the first of the three padlocks gave way and hung open.

‘Cool,’ Anton grunted, concentrating on the screws. He had removed them all from one hinge and was almost there with the second.

As he pulled out the last screw, Gunnar was still getting his breath back after the battle with the padlock.

Anton took the hammer from him, slid the claw into the opening and put his weight behind it. The door dropped out of the frame and hung on the remaining two locks on the other side.

‘Yesss!’ Gunnar crowed, his excitement obvious. ‘You win. Ice cream on me after. You’re the meanest gangster in town, man.’

He was clearly enjoying every moment.

Anton, on the other hand, was surprised at how calm he felt. He had been sure he would be more nervous. But now a warm feeling of achievement swept through him as he stepped inside the shed and the light on his helmet flickered over the boxes.

This was the first step towards his objective. He knelt down and opened the first box and began stacking sticks of dynamite in his backpack.

3

‘I’m on the visitor list,’ María said, her resentment growing deeper and stronger the longer she spent talking to the prison officer responsible for dealing with visitors.

She had booked this visit a good few days before, and refused to believe that Agla had now taken her off the list. As far as María was aware, she was the only visitor Agla ever had. Yes, the visits did seem to trouble Agla, but each one always lasted the full allotted time, even though it invariably descended into arguments and quibbling. And yes, María always had a long list of questions, which Agla usually avoided 7answering, but her visits had to be about the only variation in the routine of being locked up. At least, María assumed that this was why Agla had put her name on the visitor list in the first place. It seemed to her highly unlikely that Agla had now changed her mind.

‘You can call tomorrow to book another visit,’ the prison officer said, tugging his shirt down over his paunch and stuffing it into his waistband. ‘Agla can’t have visitors today.’

‘Why not?’ María asked, leaning forwards, elbows on the table, driving home the point that she wasn’t about to leave.

‘She’s indisposed,’ the prison officer said, peering at the visitor list and scribbling a note on it.

‘I want to know why,’ María said. ‘Or let me call her myself, so she can tell me in person that she doesn’t want a visit.’

The prison officer sighed deeply.

‘Agla can’t see any visitors today. Try calling tomorrow.’

‘I’m an investigative journalist and I demand to know why prisoner Agla Margeirsdóttir isn’t available for a previously agreed visit. If I don’t get an explanation then I’ll have no choice but to take this to the Prison and Probation Administration.’

The prison officer sighed again, deeper this time, and his eyes rolled towards the ceiling.

‘Sweetheart, this isn’t Guantanamo Bay. We have a duty of confidentiality regarding the health of inmates, so all I can tell you is that Agla is unwell today, and that you can call tomorrow and book another visit.’

Now it was María’s turn to sigh. This was as far as she was going to get for the moment. There was no point in taking out her frustration on the prison officer. In reality, she didn’t suspect there was anything untoward about Agla’s absence; she was simply impatient. This time the questions on her list were all unusually urgent – she wanted to know about Agla’s links to Ingimar Magnússon and William Tedd, the Paris-based markets guru. She had come across both names during her investigation into Agla back when she had worked on economic crime for the special prosecutor. That had been in a previous life, before Agla had, indirectly, caused her to be sacked.8

María let her thoughts wander as she made her way back to her car. Although the days had begun to lengthen, the April sun was still low in the sky, and she squinted into the brightness. It would be more pleasant when these knife-edged, blue-white rays gave way to mild spring sunshine. In this light everything seemed to be grey and forlorn after the harshness of winter. There was no sign yet of any growth and the sunshine beat down mercilessly on the dry moorland that replaced the bare earth as she left the prison behind her. Not that the time of year made any difference. She wouldn’t be taking a summer holiday to enjoy the weather. She couldn’t afford one. Her online news service, The Squirrel, just about made ends meet, but only because of the income from the handful of advertisements she had been able to secure. So far she hadn’t been able to sell her material to any of the larger media outlets. Now, though, she suspected she was on the trail of something juicy. Just the names Ingimar Magnússon and William Tedd were enough to tell her she was on the right track.

María sat behind the wheel. Her heart skipped a beat when she noticed, hanging from the mirror, the little crystal angel that Maggi had given her. That had been a year before he had left her, saying that she wasn’t the person he thought he had married. If she were to trace everything back to its origins, then the divorce could also be laid at Agla’s door. Her whole life had been wrecked when she had been sacked by the special prosecutor, and for many months she had been in a kind of angry, disbelieving limbo. Finally Maggi had given up, saying that he no longer recognised her. If she were completely honest, she no longer recognised herself either.

It didn’t do to think too much about Maggi – it would wreck her day completely. If she didn’t take care and let herself drift too far, she would end up in tears on the steps outside his place. The worst of it was that, although she couldn’t help hoping that he would ask her in and then would hold her tight, she knew full well that he would actually just look at her with a mixture of disgust and pity, before shutting the door in her face.

She started the engine and wondered whether she ought to rip the 9angel from the mirror and throw it out onto the moor. But she couldn’t bring herself to do it. Maybe she would do it tomorrow. In the morning she would call the prison and book another visit. And since she wasn’t able to ask Agla her questions right away, she would have to start on Ingimar.

4

She had been more heavy-handed than usual today – to Ingimar’s satisfaction. He was exhausted after being whipped, and he had needed her help to reach the bed afterwards. This was the best part of it, exactly why he came to her; the hour he spent in her bed on the borderline between sleep and wakefulness, overwhelmed by the adrenaline that his body automatically pumped into his bloodstream as the first lash of the whip burned into his back, and the endorphins that accumulated the longer the treatment lasted, leaving him in a daze.

In his younger years he had believed that what he craved was the humiliation – of being tied, manacled, hung from a hook and whipped; of being completely in her power. But now he knew better. The key to it was the vulnerability that came afterwards; his defencelessness as she helped him, sobbing and bruised, to the bed, where she would apply a soothing balm to his back, tuck him in and whisper sweet words that were both calming and encouraging, just like a mother with her child. This was when he felt he was truly loved; he revelled in lying in bed without having had to do anything to deserve it, not one single thing.

‘You’re a good boy,’ she whispered, kissing the top of his head and leaving the room as he began to doze. He lay there in a dreamless state for a while, he had no idea how long, until his thoughts were again clear and linear, and he felt there was no longer any need to lie still. The time for rest was over. He got to his feet, pulled on his trousers and took his shirt with him to the kitchen where she was waiting for him with a smile.10

‘Let’s take a look at you,’ she said, examining his back. ‘You’re fine,’ she added, handing him his singlet and helping him into it. It stung like hell, but he liked that. He would feel the pain for the next few days, every time he dressed, took a shower or leaned back in a chair, and that was the way he wanted it. This reminder was something he needed; the reminder that he was human. It was the same as the Roman emperors who had a slave walking behind them, whispering ‘remember you are mortal, remember you are mortal’.

‘I’ll make a transfer to your account,’ he said as he buttoned his shirt.

She stepped closer and helped him with the top button and knotted his tie for him.

‘Not too much,’ she said. ‘You always pay me too much.’

‘I’m grateful,’ he said.

‘You’re still in a state when you make the transfer, so you make it too much.’

‘It’s no more than you deserve,’ he said, kissing her cheek.

‘Now you be a good little worm and do as you’re told.’ She smiled and winked as she teased him. ‘Otherwise you’ll feel it…’

He gave her an exaggerated bow.

‘Yes, madame!’

They understood each other instinctively. She knew precisely when it was safe to inject a little humour into the game they played, and when things had to be kept serious as it was crucial to not lose the momentum.

‘Call me whenever you want,’ she said, holding the front door open for him.

He blew her a kiss on his way down the steps, and as was so often the case, he was astonished at the change he’d undergone since he had turned up here a couple of hours ago. He had walked in tense with stress and with his mind in overdrive, but now he was relaxed and his thoughts had clarified, as if his soul had been cleansed.

He started his car and turned up the heater. It wasn’t particularly cold, but a whipping always left him with a chill that lasted a few hours. His phone showed one missed call and two text messages, all from the 11same number. He opened the first message. It was a long one, from an investigative journalist called María. He sighed. He knew who María was: a former investigator at the special prosecutor’s office who had fallen badly out of favour and who now ran her own online news outlet, an effort driven forwards more by determination than ability. She was the type who saw conspiracy everywhere she looked and who could make the most innocent thing look suspicious. The message was a series of questions concerning himself and Agla, and any business connections they might have.

That was something he could answer easily. Right now there were none. They had ended their joint business affairs some years before and since then had taken care to avoid each other.

He opened the second message and the flood of questions continued. This demonstrated an incredible optimism on her part. Surely she didn’t expect him to answer all these questions by text message? Normally he kept clear of journalists and wouldn’t have hesitated to delete these messages right away.

But the last question in the series troubled him:

What is the nature of the business conducted by yourself and William Tedd with Icelandic aluminium producers?

5

If she had imagined during the weeks before she’d sat down in front of the radiator with the noose around her neck that she couldn’t possibly have felt worse, she was wrong. Those days had been a walk in the park compared to waking up after trying to kill herself.

The pain of renewing her acquaintance with life, having already waved it a final goodbye, was so unreal, she wasn’t even able to feel angry with herself for making a mess of it. She opened her eyes and saw that everything around her was white, which told her she had to be in hospital. She closed her eyes again and hoped that she might slip back into unconsciousness. But it was hopeless. She was awake and a prison 12officer she knew was called Guðrún was in a chair at her side, leafing through a magazine.

‘How are you feeling?’ Guðrún asked, ringing a bell.

Under the circumstances, this was a bizarre question, and there was only one possible reply: bad. Agla tried to form the word but all that came out of her throat was an indistinct growl that could have been made by a wild animal. That would have to be a wounded, angry animal.

A woman in white scrubs came in and looked her over.

‘Don’t try to talk,’ she said. ‘Just rest and drink cold water. Your throat is still swollen and you’ve not long come off the ventilator, which will have left your throat sore as well. I’ll get you some water and painkillers, and the doctor will be along to talk to you.’

She looked into Agla’s eyes, and laid a hand on her arm, squeezing it briefly. Then she smiled and left the room. This tiny sign of human warmth was like a punch to the stomach, and Agla could feel tears flowing from her eyes and down onto the pillow. Self-pity wasn’t something she made a habit of, regardless of how tough things might be, but somehow this was pushing humiliation to a new level. A screwed-up attempt at death had become the perfect summation of a screwed-up life.

The nurse returned with a painkiller that she pumped through the cannula in the back of Agla’s hand. Then she spooned up an ice cube from the water glass at Agla’s side and lifted it to her lips. Agla opened her mouth like an obedient child and took the ice cube just as she felt the morphine take over. In a second, everything became a little better. The tears stopped flowing from her eyes, and she felt there was a security in having Guðrún at her side, again deep in a magazine.

Agla came round to the sound of the doctor’s deep voice, which somehow had seemed to grow louder inside the void of her unconsciousness. Maybe he had been standing there talking for a while.

‘You were lucky,’ he said. ‘You were extremely fortunate that the rope stretched almost enough to let you sit; it meant your bodyweight wasn’t concentrated entirely on your neck. Otherwise you’d have broken it, 13and damaged your spinal cord too. But as the rope stretched and you weren’t hanging there for long, we’re only looking at damage to your airway, and some swelling and bruises. Even your larynx is in pretty good condition. So you’ll be in here overnight and then you should be able to go home tomorrow,’ he said. Then he glanced at Guðrún, who coughed gently. ‘I mean, you can be discharged tomorrow.’

Agla blinked slowly instead of trying to nod her head, as her neck was still too stiff.

The doctor turned to leave.

‘There’ll be a psychiatrist coming to see you later today. That’s the rule when this kind of thing happens,’ he added from the doorway.

When this kind of thing happens, Agla thought to herself. Why doesn’t he just say when people try to kill themselves?

6

Júlía tiptoed up to the school steps, where Anton stood with his back to her, and slipped her little finger into his hand. He responded by twisting his little finger around hers. This was their special thing, an expression of what passed between them and their main physical connection. Anything further had been forbidden, which in itself had been unbelievably embarrassing, but hadn’t actually changed things much. They could still spend all the time they wanted together, her father had said when he had visited Anton’s father to ‘talk things over’, and they could go to each other’s houses and see each other, just as long as their bedroom doors remained open.

Anton had seen how his father had been taken by surprise by this visit, and how he had tried to hide it. To begin with he had used small talk, and had filled the old man with coffee and biscuits to stifle any serious conversation. Then, much to Anton’s surprise, he had agreed with Júlía’s father. Anton had expected him to go along with what his son was doing without saying a word. But instead he had announced to Anton in his grave voice that if he was serious about the girl, then he 14could wait. And Anton could wait. Everyone at school knew they were together, so none of the other boys dared go anywhere near her, which meant that he could be sure she was his; the prettiest girl in the school. In fact, she was easily the prettiest girl he had ever seen. Of course they broke the rules; they kissed and cuddled when nobody could see them, but it wasn’t often, as he could sense that she was uncomfortable with disobeying her father, and he didn’t want to pressure her. As his father had spelled out to him, if he wanted to hold on to the girl, then he would have to behave in a way that made her feel safe around him.

So he tried to do everything he possibly could to make sure that she had a feeling of security when she was near him.

He gently squeezed her little finger and turned his head towards her.

She smiled.

‘Shall we go to the pictures tomorrow?’ she asked.

‘Dinner and a movie?’ he suggested with a wink. That had to mean a burger or a kebab, followed by a bus ride to the cinema. It would be her birthday soon, and he had decided he would take her out somewhere smart, a shirt-and-tie place, and he’d have to do a deal with his father to cover transport and some extra finance.

By then he would also have given her the birthday present. This was what he had dreamed of for so many weeks. He was certain that it would be the best moment of their whole lives.

‘Talk to you this evening,’ she said as Gunnar cruised up to the school steps on his moped, which was still muddy from the night before.

‘Talk to you this evening,’ Anton said, squeezing her little finger again. There was no need to say it, as they talked every evening and sent each other endless messages and chatted online. As well as being the prettiest, she was the most fun girl he had ever met.

He hopped onto the moped and held on tight to Gunnar’s coat as he set off. They had agreed to meet after school to find a better place to store the dynamite, and to think over the problem of detonators. He had been sure that they would find detonators in the shed as well, but there hadn’t been any. They had searched everywhere to be certain. They would just have to find some other way to set the dynamite off.15

7

‘If you get a call from a journalist called María, phoning from Iceland, then don’t give her any chance to ask you anything,’ Ingimar said once he and William had exchanged the usual greetings.

The background music he could hear down the line told him that William was out enjoying himself somewhere. The man was a well-known party animal who never let a celebration or a gathering pass him by. He reminded Ingimar of a younger version of himself. Back in his younger days he had the same kind of energy that allowed him to spend a night on the town and be awake and ready for a tough day’s work after only three hours’ sleep. As far as he was concerned, that was now all in the past. But the same didn’t apply to William.

‘I’m at a friend’s birthday party,’ he said, his strong American accent coming across clearly. ‘You’d have had a great time.’

Ingimar knew what that meant: fine wines and fine women. He leaned forwards and used the car’s mirror to inspect the grey in his hair. For a second he felt a touch of regret for that life – but in fact he did not miss it. These days he could knock back wine at whatever time of the day he wanted to without feeling it, and he had pretty much given up chasing women. She didn’t count. That wasn’t chasing skirt. That was something different.

‘Everything looks good,’ Ingimar said. ‘This María is just fishing, but I wanted to warn you anyway. She’s one of those annoying people who doesn’t understand when to lay off. She’s trying to connect Agla with our project, and we need to be careful, we don’t want her getting mixed up in this.’

‘Why? Don’t you like Agla?’ William laughed, and, as if to underscore the glamour of his party, an up-tempo salsa number struck up in the background.

‘It’s not that I don’t like Agla. Quite the opposite. It’s just that if she gets the slightest inkling of what we’re up to, before we know it half the profits will end up in her pocket,’ he said.

William roared with laughter.16

‘That’s her, right enough,’ he said. ‘Now get yourself to Paris, mon cher Ingimar. I’m on the trail of a sweet little thing here who has a twin sister. So we could be up for a memorable double date!’

Ingimar smiled to himself. He enjoyed William’s zest for life. Americans were so delightfully shameless about their pursuit of pleasure.

‘Speak soon,’ he said, and ended the call.

He would certainly have enjoyed a trip to Paris, where he could have had William entertain him. But over the last few years it was as if life itself had tracked him down, and responsibility, which was something he had never worried much about, had become an increasing burden. Anton needed him close by, especially considering what his mother was like.

He took a deep breath and got out of the car. As he walked up to the house, his feet seemed unusually heavy. He slipped the key into the lock and opened the door silently. Inside there was silence, and all of his senses seemed to detect the stale aura of unhappiness that filled the house.

8

María felt the same stab of shame every time she entered the building where The Squirrel had its office, because on the other side of the corridor was her landlord, the nationalistically inclined Radio Edda, which played bad Icelandic music and appeared, according to the quality of its discussion programmes, to place a particular emphasis on removing rights for minorities. She would have preferred to locate The Squirrel somewhere else, but she couldn’t afford it. The rent at Radio Edda was well below the market rate for this central area of the city, but being here saved her a great deal of driving compared to an office somewhere on the outskirts. Still, even though it was cheap, she always felt the urge to hide her face every time she entered or left the building. Over the doorway hung the station’s slogan: Iceland for Icelanders.

She was hardly inside the office when Marteinn came hurrying in behind her.17

‘Brown envelopes, María. Brown envelopes, stuffed with cash that change hands at Freemasons’ meetings. Freemasons, María!’

She stared at him questioningly. He had that peculiar glint in his eyes that made him look like a startled horse and that indicated he was heading for a psychotic episode.

‘My dear Marteinn,’ she said. ‘Don’t you think you ought to be on your way to the doctor?’

‘No,’ he said, sitting at his desk.

It would have been an exaggeration to say that Marteinn was her colleague. He was more like an adopted pet who came and went, always on his own terms. She let him write a daily column in The Squirrel with the title ‘The Voice of Truth’, and in between he helped by digging out information. When his health was in good shape, he was remarkably skilled at searching out all kinds of oddities on the internet, although María suspected that he occasionally hacked into secure computer systems to get what he wanted. She had long since given up trying to manage him. He wasn’t exactly staff, as he never asked to be paid. Having someone on board who made an effort without invoicing for it was a real positive, though he wrote pleasantly barbed articles that often attracted attention, and it made a difference to not be a completely solo operation. It was almost like having a proper job when she sat down and had a cup of coffee with him while they talked over his latest conspiracy theory.

‘Don’t you think you ought to get your medication checked?’ she said now. ‘Shouldn’t you go to the clinic before they close for the day?’

‘No,’ he said with determination, hunching over the computer that sat among the piles of junk on his desk like a fledgling in a nest. ‘I need to write this article first.’

‘You’ve already given me enough for the whole of next week,’ she said.

‘But this is about the bribes that are paid to ensure that the pollution readings around the smelter are always within limits. This is what happens when the Freemasons meet, María. And people need to know about it!’18

She sighed. He seemed to come up with a new conspiracy theory twice a day, most of them involving the Freemasons in some way or other. She had to admit that most of the time she enjoyed his presence, and occasionally he would pick up something that wasn’t too far-fetched and that sparked her interest enough to make it worth checking out. But the sources of his theories weren’t always the most reliable.

‘Where did you hear about it?’ she asked.

‘What?’ He looked up and stared at her, his eyes blank. ‘Hear about what?’

‘Brown envelopes changing hands to ensure that pollution readings are always acceptable.’

‘Oh, that,’ he said, turning back to the computer, his fingers hammering the keys. ‘I had a dream about it.’

María groaned. She stood up and went out into the corridor to go to the toilet, promising herself that today she would count how many times she needed to go. It wasn’t normal how frequently she needed to pee, and how quickly the urge to go would grow. Only a minute or so had passed since she knew she had to go, and now she was so desperate that she was afraid she might wet herself, particularly as this damned metal door wouldn’t shut behind her. She kicked it so that it settled into its frame and then squatted on the toilet with relief.

Marteinn was a worry. If he didn’t agree to go to the mental health clinic by himself, then she would have to take him. It wouldn’t be the first time. More than once she had spent a day trying to keep him calm in the waiting room until it was his turn to see the doctor. It would be worthwhile trying to get him to go before he became even more of a mess, suspecting everyone and everything around him, her included.

9

‘Oh, Agla,’ said Ewa, the prison officer with the Polish roots, when Agla appeared in the reception suite accompanied by Guðrún, who was carrying the bag of medication Agla was supposed to take.19

Guðrún handed the bag to Ewa to deal with, but Agla was still finding it difficult to speak, so she just nodded to Ewa and looked away. She was consumed by a sudden desire to apologise to Ewa, as if she owed her a debt for the friendliness she had shown her since she had started work at the prison, but she was still in too much of a daze. Ewa took her arm and led Agla – cautiously, as if she were fragile – along to the female corridor.

‘Let me know if you need anything,’ she said in a low voice. ‘Whatever it is. There’s nothing so big or so small that I can’t try and fix it.’

Agla smiled weakly. Although Ewa was always ready to help, she couldn’t give her back her life, take those bad decisions back, neatly tie up the loose ends, or rewind a couple of decades. And she couldn’t assuage the pain of losing Sonja, which still only left her for a few moments at a time.

More than four years had passed since Sonja had vanished from her life, leaving only a short text message that simply stated that she couldn’t do this any longer. Agla had sat numb on the unopened boxes in the huge house she had bought for them and replayed their every conversation over and over in her mind as she searched for an explanation. Now, all these years later, she still had no understanding of why Sonja had left her, and the rejection still seared.

Ewa squeezed her arm gently as she left her at the entrance to the female wing. Agla went straight to her cell. The door stood open, and she was panicked by a thought: would the noose still be hanging from the radiator? But then she saw someone lying in her bed.

‘Hæ,’ the girl said, sitting up. ‘You’re supposed to be on suicide watch, so you’re in the security cell and I’m in here now.’

Agla stared at her and her eyes scanned the cell. It was as if she was in a dream – reality had been shoved to one side and twisted. She recognised the place, but didn’t. There were clothes all over the floor, a suitcase was open on the desk and the girl on the bed was surrounded by scattered sweet wrappers.

‘Did you try and top yourself?’ she asked, putting a piece of chocolate in her mouth. ‘Sorry, I was in rehab right after I was sent home 20from Holland to finish my sentence here, and now I’m completely hooked on sugar.’

Agla opened her mouth to ask who she was, but stopped. There was still no sound coming from her larynx, and it was even painful to whisper. It was no business of hers who this skinny, scruffy bitch who had stolen her cell might be. She turned in the doorway and went to the cell at the end, next to the door to the communal area, and there she found her things. One of the warders had laid out her personal stuff on the shelf in the bathroom and stacked her books on the table, but her clothes were still folded up in a cardboard box.

Agla let herself fall back on the bed and stared up at the all-seeing eye of the security camera that glinted in its glass dome in the middle of the ceiling. There seemed to be no end to this fuck-up. For the coming days and weeks, she would have to put up with being streamed live.

10

Ingimar sat for a long while at Rebekka’s bedside, watching her sleep. She was lying just as she had been the night before when he had come to check on her – on her left side with her right hand under her cheek, her left hand oddly stretched out and resting on the bedside table. The wedding ring had twisted around on her finger so that the diamonds were on the palm side. This was not what he had foreseen eighteen years before, when he slipped that ring onto her finger. But that’s the problem with passion; it blinds you to what would actually be better for you. It would have been better for him to have remained unmarried.

There would undoubtedly be several hours before she would emerge from her drugged mist, and it was just as likely that she would reach out for the box of tablets on the bedside table and go back to sleep instead of getting up. With one finger he steered a stray lock of hair from her face and let it rest behind her ear. She did not stir, but muttered something unintelligible, and a thin bead of saliva leaked from her mouth into the pillow.21

Ingimar stood up and went to his own bathroom, which had originally been a guest bathroom, until they had started to sleep separately. There had been no decision to sleep in different rooms, but he had not been able to sleep next to her when she was so heavily drugged. It seemed as if her complete immobility woke him repeatedly during the night, and every time, when he saw that she had not moved at all, he was struck by a deep discomfort. Before he could go back to sleep, he felt he had to put an ear to her mouth to be sure that she was still breathing. This feeling of unease ultimately became something he could no longer tolerate.

One night he had moved to the divan in the guest bedroom and had slept like a log, as if her shallow breaths in the next room were no longer any business of his. Within a few weeks the divan had been replaced by a bed. So the guest bedroom had become his bedroom, and the guest bathroom had become his personal space. Not that it mattered, as they no longer ever had guests.

He went downstairs, switched on the coffee machine and then made cocoa for Anton, carried it upstairs and sat by his bedside until he began to stir. Since he had entered his teens the boy seemed able to sleep around the clock. Ingimar had never needed much sleep; all his life he had been a morning person, awake and active. But people are different. He reflected that at Anton’s age, he had already been a fisherman.

Once Anton was sitting up in bed, Ingimar went to the bathroom and turned the shower on, lathering his face with shaving soap as the hot water began to run. As always, he shaved as he stood under the flow of water. The skin on his back stung under the heat of the water, so he finished with a blast of water so cold it made him gasp.

He dressed and said goodbye to Anton, then went into the kitchen and poured coffee into a paper cup to take with him. He put on his overcoat and looped his scarf around his neck, closing the door behind him on his way out. There was something special about taking a breath of the fresh outdoor air, and for a moment he felt as if he had surfaced from a long dive underwater, lungs thirsty for oxygen. He felt a new lightness now that he was out under the open sky.22

What was so peculiar was that around the time of the financial crash, his life had also fallen apart. It hadn’t been the collapsing banks that had hurt; the opposite was the case, as there were more business opportunities than ever before, and the profits were in excess of anything he could have dreamed of. There had been a crisis of another kind. An inner one. In the wake of this turmoil, he had found himself caught up in woman trouble, having made the mistake of sleeping with the same girl several times, in the process becoming captivated by her. He had taken the decision to ask for a divorce, but it became clear to him that there could be no such thing. He could not part with Rebekka now that she was in the state that he, admittedly indirectly, had got her into. And he couldn’t leave Anton behind. Although Anton didn’t conceal his disdain for his mother from her, Ingimar knew that if it came to the crunch, the boy would rather live with her than with him. Anton was in the same position as Ingimar, not daring to leave Rebekka on her own.

Ingimar walked with steady strides, but slowed his pace when he heard his phone buzz in his coat pocket. He took it out, glanced at the screen, and saw that this wretched journalist woman wasn’t going to give up. Now her questions were about how high the bribes had been to ensure that the pollution readings for the smelter remained within acceptable limits. He smiled. This was a weird kind of journalism; it was as if the woman was churning out endless conspiracy theories in the hope that one day she might accidentally hit on a true one.

11

A