Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: An Áróra Investigation

- Sprache: Englisch

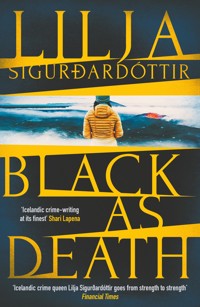

When the chief suspect in the disappearance of Áróra's sister is found dead, and Áróra's new financial investigation leads to the street where her sister was last seen, she is drawn into a shocking case that threatens everything … The unmissable finale to the chilling, twisty, award-winning series… 'Icelandic crime-writing at its finest' Shari Lapena 'Icelandic crime queen Lilja Sigurðardóttir goes from strength to strength' Financial Times 'A heartbreaking story and a twisty mystery that will only be fully appreciated by those who have read the other parts of the quintet first. You won't regret it if you do' Sunday Times 'So chilling' Crime Monthly _______ A final reckoning… With the fate of her missing sister, Ísafold, finally uncovered, Áróra feels a fragile relief as the search that consumed her life draws to a close. But when Ísafold's boyfriend – the prime suspect in her disappearance – is found dead at the same site where Ísafold's body was discovered, Áróra's grip on reality starts to unravel … and the mystery remains far from solved. To distract herself, she dives headfirst into a money-laundering case that her friend Daníel is investigating. But she soon finds that there is more than meets the eye and, once again, all leads point towards Engihjalli, the street where Ísafold lived and died, and a series of shocking secrets that could both explain and endanger everything… Atmospheric, dark and chilling, Black as Death is the breathtaking finale to the twisty, immersive An Áróra Investigation series, as Áróra and her friends search for answers that may take them to places even darker than death… Perfect for readers of Camilla Läckberg, Karin Slaughter, Eva Björg Ægisdóttir and Jo Nesbø. ____________ 'It is a testament to any writer's skill to sustain such a compelling narrative across five novels, yet Sigurđardóttir achieves this with remarkable ease. From the opening of Cold As Hell through to the conclusion of Black As Death, this has been an epic tale told with intimacy and unwavering command' Nordic Watchlist Praise for the An Áróra Investigation series 'A blast of Icelandic Air' The Times 'A terrific tale with twist after twist' Sunday Times 'Your next literary thrill' Vogue 'So atmospheric' Crime Monthly 'Action-packed and pacy … I would like to be Áróra's best friend' Liz Nugent 'The Icelandic scenery and weather are beautifully evoked…' Daily Mail 'Chilly and chilling' Tariq Ashkanani 'Tough, uncompromising and unsettling' Val McDermid 'A dark, twisty and pitch-perfect thriller' Michael Wood 'Another bleak, unpredictable classic' Metro

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 310

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iTHANK YOU FOR DOWNLOADING THIS ORENDA BOOKS EBOOK!

Join our mailing list now, to get exclusive deals, special offers, subscriber-only content, recommended reads, updates on new releases, giveaways, and so much more!

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Thanks for reading!

TEAM ORENDA iiiiiiv

vviviiviii

BLACK AS DEATH

Lilja Sigurðardóttir

Translated by Lorenza Garcia

BLACK AS DEATH

CONTENTS

PRONUNCIATION GUIDE

Icelandic has a couple of letters that don’t exist in other European languages and which are not always easy to replicate. The letter ð is generally replaced with a d in English, but we have decided to use the Icelandic letter to remain closer to the original names. Its sound is closest to the voiced th in English, as found in then and bathe.

The Icelandic letter þ is reproduced as th, as in Thorleifur, and is equivalent to an unvoiced th in English, as in thing or thump.

The letter r is generally rolled hard with the tongue against the roof of the mouth.

In pronouncing Icelandic personal and place names, the emphasis is always placed on the first syllable.

Áróra – Ow-row-ra

Baldvin – Bal-dvin

Björn – Bjoern

Engihjalli – Eng-e-hjattly

Grímur – Gree-muhr

Gúgúlú – Gue-gue-lue

Hafnarfjörður – Hap-nar-fjeor- thur

Hringbraut – Hring-broyt

Hvolsvöllur – Kvols-vull-uhr

Ísafold – Eesa-fold

Keflavík – Kep-la-veek

Kristján – Krist-tyown

Lauganes – Loega-ness

Laugardalur – Loe-gar-dahlur

Laurus – Low-rus

Miklabraut – Mikla-broyt xii

Oddsteinn – Odd-stay-tn

Reykjanes – Rey-kjah-ness

Seltjarnarnes – Sell-tjar-nar- ness

Seyðisfjörður – Say-this-fjoer-thur

Síðumúli – seethu-mooli

Snæþór Ómar – Snie-thor Oh-mar

Sturla – Sturt-lah

Sæbraut – Sigh-broyt

Vatnajökull – Vat-n-a-yer-kootl

1

‘You know what to do, Ísafold,’ her sister Áróra would doubtless have said, and Ísafold could imagine the weariness in her voice. Áróra had always been so dogged, so ready to fight her sister’s battles for her, but the last time Ísafold contacted her, it was obvious she had given up on her. ‘Call the Women’s Shelter,’ Áróra had told her then, and Ísafold had whispered back: ‘I know, I know. But I’m locked in the bathroom right now, and I don’t know if he’s gone to bed yet so I’m afraid to go out.’

And here she was, a few weeks later, in the same situation. She gave a sniff and dried her face on the towel. She didn’t have a nosebleed, at least. The towel would be red otherwise. Björn had punched her straight in the face, but the blow had caught her cheek. Then he’d grabbed her round the neck and squeezed hard. This time she came close to blacking out before he’d let go.

The bathroom window was open, but she didn’t dare get up to close it; she felt safer where she was, sitting on the floor. The door was locked, however Björn would often kick it, and she was scared the lock might give way, so she sat with her back against it, feet braced against the tub. She was clasping her phone in her hand and staring at it. Áróra was the only person in the world she wanted to call. To confide in. The last time she did that, though, Áróra had told her to call the emergency services. Ísafold felt a wave of dread rise inside her and almost threw up.

‘No,’ she’d whispered then. ‘He’ll only be even angrier tomorrow.’

‘You see!’ Áróra had declared, with an air of triumph. ‘You’re already thinking about what will happen when you go back to him. How can I take seriously what you said just now, about being ready to leave him this time? Yet you expect me to fly over to Iceland to2rescue you or … or what? I don’t even understand what it is you want me to do.’

‘I don’t either,’ Ísafold had breathed into the phone, feeling her voice falter. It was only this sense of aloneness she’d felt the need to share with her sister. And she had that same feeling now. She needed to convey to someone she trusted how utterly alone a person is in the face of violence. How the pain of the blows almost pales in comparison to the aching loneliness that fills one’s whole being. Yet she had never been able to convey this to Áróra, nor would she succeed now if she called her. Áróra was so sorted. Áróra was so strong. Áróra had no problem hitting back.

‘How many times have I dropped everything to rush over to Iceland to try to help you?’ Áróra had said that last time they’d spoken. ‘Only for you to go back to him before the black eye he gave you has even healed.’

‘I don’t blame you for giving up on me,’ Ísafold had whispered then, and her sister had sighed at the other end of the phone.

‘I haven’t given up on you, Ísafold,’ Áróra replied wearily. ‘I just can’t be responsible for you anymore. You know your options and you can decide for yourself. If you don’t want to involve the police you call your brother-in-law, Ebbi, and he’ll come straight over to fetch you. You’ve been through it all before so you know the drill. I don’t see what good I can do by rushing over to Iceland to hold your hand.’

If Ísafold called her sister now, Áróra would simply repeat the same thing. And she’d be justified. It was unfair of Ísafold to want to share her suffering with her sister. Áróra had the right to live her perfect life in peace, without Ísafold imposing her misery on her.

Ísafold dabbed her face again with the towel; the salty tears stung her cheek.

‘I think,’ she whispered into the silence, ‘I think he’ll end up killing me soon.’

MONDAY

2

The rain was bucketing down, so Felix sat in his car for a while, in the hope the downpour would stop, or at least subside a little before he ventured out. He turned on the radio breakfast news but couldn’t concentrate. His mind was a blur and he felt dreadfully sleepy, having woken up earlier than usual to begin his rounds for Sturla before noon. This was because the previous afternoon he’d been unable to get hold of anybody; it was as if they’d conspired to make themselves scarce, so that, eventually, he’d given up and gone home.

It didn’t look as though the rain would let up anytime soon. He’d have to brave the short distance between the car park and the apartment block and hope he didn’t get drenched. He zipped up his jacket, turned his collar up and silently cursed himself for not having worn his usual hoodie; the rain would mess up his hair, which had taken him so long to fix that morning – getting the middle parting straight, arranging his fringe so it fell over his forehead just the way he liked. He took a deep breath, stepped out of the car and made a dash for it across the car park, slowing down only when he’d reached the passageway that led from the street to the apartment block. There, he shook himself as might a dog and stood still for a moment to allow his heart to calm down.

His first stop was the Hippy – an ageing, small-time dealer who’d been selling grass for years and had recently branched out into pills. Felix knocked on the man’s door and had to wait a while before he came to open it. His long hair was dishevelled and his eyes looked bloodshot. 4

‘Felix,’ he murmured, handing him a bundle of notes. ‘Tell Sturla I’ll give him the rest next week, will you?’

Felix gave a nod, and a feeling of dread gripped his throat. He gave a little cough: ‘You know Sturla doesn’t like it when people are late with their payments.’ He didn’t need to tell the Hippy this; Sturla had a reputation for being a hard-ass, and his debtors could expect to pay with their blood. And not only his debtors, his debt collectors, too. Felix truly didn’t look forward to passing the Hippy’s message on to his boss.

His next stop was the Bartender. Felix arrived when the bar was being cleaned – chairs were upside down on the tables, and although the doors and windows had been flung wide open, the stench of stale beer seemed to have impregnated the paintwork, and the only effect of the detergent was to create a nauseating cocktail that made Felix want to retch. The Bartender instantly slid an envelope across the counter.

‘It’s all there, plus a bit extra to compensate for last week,’ he said. ‘Be sure to mention that to Sturla, will you?’

‘I will,’ Felix said, stuffing the envelope into his pocket. ‘Consider yourself lucky Sturla didn’t come here in person to collect what was owing.’ The flash of fear he saw in the Bartender’s eyes made him feel better. It was good they all knew Sturla was monitoring things. It made his job easier. He disliked having to beat people up.

3

‘Any news about the investigation?’ Áróra said, not really sure why she was asking. They had only planned to meet for lunch, as they sometimes did, but it had made Daníel so awkwardly happy that Áróra reproached herself for not taking the initiative to organise these treats more often.

‘You know I can’t discuss an ongoing case with you. Even if it does relate to your sister. Besides, I’m no longer part of the investigation. Gutti is in charge of it, as you well know, Áróra.’

‘Still, you must be following their progress, keeping abreast of what’s going on,’ she said, and instantly regretted it. From the expression on Daníel’s face, she realised she’d probably insisted too much. He assumed a faraway look, avoiding eye contact, and she could almost hear the mental drawbridge going up. But this wasn’t only about not discussing the case with her. He knew something – something he hadn’t yet told her.

‘It has to go through the proper channels,’ he said at last. ‘Can’t we just enjoy this delicious food?’

Áróra nodded, contemplating the plate of salad before her. It contained all her favourite ingredients – avocado, feta cheese, spinach, chickpeas, with a tasty dressing on top – but she wasn’t hungry. Even though lunch had been her idea. The food hall at Hlemmur was their habitual meeting place: it was handy for Daníel to nip across the road from the station, and easy for them both to find the food that suited them. Áróra needed something light as she’d be heading to The Gym afterwards to lift weights, whereas Daníel seemed to have no trouble putting away two square meals a day.

‘I’m sorry, Daníel,’ she said, sliding her hand across the table. He clasped hold of it, squeezing it gently, then stroked the back 6of her hand with his thumb, sending a frisson of pleasure up her arm that spread through her whole body. She felt a flash of embarrassment and glanced at the tourists sitting at the nearby tables. Of course, no one was paying any attention. Why would anyone be interested in whether a couple held hands or not? She returned the gesture. ‘I can’t help feeling strange, knowing a whole team is over there looking into Ísafold’s death, and I have no idea what’s going on. We’ve waited four years, and now, at last, when the case has taken off again, it’s hard not knowing whether they’ve found something new.’

‘Anything new,’ Daníel echoed, cutting in. ‘Look, cold cases like this are always tricky, and—’

Now it was her turn to interrupt. ‘There is something new. I can see it on your face, Daníel. I know you well enough by now to see when you’re keeping something from me. And the longer you keep it from me, the more awkward things will get between us. Whenever I mention Ísafold’s name you get that evasive look. I know you’re hiding something from me.’

Daníel struggled for a moment to cut up the duck thigh on his plate, then shovelled two forkfuls into his mouth, chewing vigorously and with an air of irritation. Then he emptied his glass of water in one gulp and rose swiftly from his chair.

‘All right,’ he said.

‘All right?’ she repeated, not sure how to interpret this abrupt end to their meal.

‘Let’s cross the street and talk to Gutti. There’s something he needs to tell you.’

4

Daníel checked his phone as they mounted the steps of the police station. There was nothing pressing, and he hoped it would stay that way so he could accompany Áróra when she spoke to Gutti.

He’d been dreading this moment for a few days, ever since, anxious for an update about the investigation, he’d dragged the information out of Gutti and Helena. At the same time, he was relieved, because he’d been forced to behave towards Áróra as if he knew nothing. But it hadn’t worked. It never did. She always saw through him.

There was nowhere for them to sit downstairs, so they installed themselves in the nicer canteen on the top floor; it wouldn’t matter if they took it over for a while as hardly anyone used it, and if somebody did decide to sneak in to use the good coffee machine they’d see through the windows in the corridor that an interview was taking place. Besides, it was cosier in there than in one of the bleak downstairs offices. The carpet tiles on the floor and one wall had the effect of softening any sounds, and the row of windows looking out onto Mount Esja offered the eyes, as well as the soul, a chance to find repose in its blue-green hues.

Daníel wasn’t sure how Áróra would respond – only that she would take it badly. She’d either adopt a tough attitude, snap at them, and say they had no right to withhold such an important piece of information from her, in which case it would take him days to calm her down. Or she’d be depressed and hurt. This would undoubtedly be worse. He didn’t know how to handle her when she retreated into herself.

After the discovery of her sister’s body earlier that spring, the 8strength Áróra had previously shown became fragile, the shell she’d so carefully constructed around herself threatening to crack at any moment. Despite long claiming she had no hope of her sister being found alive, the finality of knowing had somehow amplified her pain. As if she’d been holding part of her grief at bay until her sister’s death was confirmed. Until they found her body.

Daníel had just finished setting out the coffee cups when Gutti walked in and closed the door behind him. He shook his head when Daníel pointed inquiringly at the coffee machine, and sat down at the table opposite Áróra. Gutti wasn’t carrying anything. Neither his phone nor a report file of the sort detective chief inspectors habitually clutch, as they might a safety rope. It was always possible to open such a file and flick through its contents if an interview got a bit awkward, as if they’d suddenly thought of something they had to check, when in fact they looked up any information they needed on the police database – LÖKE.

‘Well, Áróra, my dear,’ Gutti said, in a voice so benign he couldn’t be criticised for employing a term of endearment that suggested a familiarity that didn’t exist. Gutti had only been involved with the Ísafold case for a few weeks, and had struggled to get up to speed, both with the missing-person investigation, as well as the discovery of the body. The two bodies. And this was where Gutti decided to start. ‘We have the remains of two individuals,’ he said. ‘Your sister, Ísafold, and her partner, Björn, and as you’re aware this discovery entirely contradicts our initial theory that Björn killed Ísafold before fleeing to Canada.’

Áróra said nothing, simply nodded. Daníel contemplated her face, but couldn’t read her thoughts. Her expression gave nothing away, other than that she was waiting expectantly. Waiting to hear what Gutti was about to tell her.

‘I assume you know, through Daníel, how police investigations work,’ he resumed. 9

But Áróra shook her head. ‘Not really. Daníel and I haven’t been together long enough for me to become any kind of expert on the subject.’

Gutti was slightly taken aback by her brusque response but quickly collected himself. ‘Yes, no, no. Right.’ He cleared his throat. ‘What I ought to have said is that in cases like these we sometimes choose to withhold certain details. For a limited time, of course. These are often details that risk causing a stir in the sensationalist media, upsetting the victims’ families, or elements we can use to verify the statements of people who claim to know something. Usually they relate to some characteristic, some peculiarity of the case, or in this instance…’ Gutti sighed then drew a deep breath, making his shirt stretch over his ever more prominent beer belly ‘…about the victim. Your sister.’

‘What?’ Áróra was now staring straight at Gutti, who shot a sidelong glance at Daníel, as though hoping he might help him out.

He had no intention of doing any such thing; he would never have chosen to withhold this information from Áróra if he’d been leading the investigation. ‘Tell her,’ he said.

‘Yes. Ahem.’ Gutti gave another little cough, and glanced furtively at Áróra, as though afraid to look her in the eye. ‘The result of the autopsy revealed an interesting … or, how should I put it? … a curious detail regarding Ísafold’s body.’

‘What?’ Áróra repeated, only now her tone was different. Now she sounded scared. Hesitant. As though she wasn’t sure she wanted to know more.

‘Her heart was missing.’

‘What?’ Áróra shook her head in disbelief, as if Gutti’s words hadn’t registered. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Whoever killed Ísafold apparently … Well. They removed her heart.’

Áróra made as if to speak, then turned her head slightly and 10gazed out of the window open-mouthed, the way a baby needing to rest its overstimulated senses might avert its eyes while it processes new experiences. Just then a big cloud scudded across the northern sky, casting a dark shadow over Esja.

Áróra turned once more to Gutti. ‘What about Björn? Was his…?’

‘No,’ Gutti replied instantly. ‘Björn was intact. I mean, none of his organs were missing. Only a few broken bones due to his body being crammed into the suitcase—’

‘Too much information,’ Daníel cut in, but Áróra shook her head.

‘No. I want to know,’ she said. ‘I want to know everything.’

Gutti now looked her in the eye and nodded. ‘I understand. But in fact, the information about the heart is the only detail we’ve kept to ourselves, because – how shall I put this? – it suggests a different type of murder than the ones we’re used to dealing with here in Iceland. As we already told you and your mother, due to the multiple injuries her body presented the autopsy was unable to determine the precise cause of Ísafold’s death, and this is the only additional piece of information. That her heart was missing.’

5

Áróra refrained from screaming until she and Daníel were outside, on the police station steps. The heavy traffic around Hlemmur and two buses accelerating mostly drowned out her cries.

‘How could you keep this a secret from me?’ she yelled, pushing him away when he made to embrace her. She did not want to cry. She did not want his pity. She was furious, seething with righteous indignation.

‘I heard about it a few days ago and I asked Gutti to tell you…’ he began, but she didn’t want to listen to him. She didn’t want to be softened by that calm voice of his that was so good at soothing her.

‘Her heart, Daníel! Her heart!’ she cried, unsure herself what she was trying to express, only that there was something particularly painful about her sister’s heart having been ripped out. She wouldn’t have given a damn about a missing kidney. That would’ve been different. But a person’s heart was somehow so central to their being. The dwelling place of emotions. Life’s metronome.

‘Áróra, darling…’ Daníel made another attempt to embrace her, but she pulled away, folding her arms across her chest, and he backed off again.

She swallowed the lump rising in her throat and gave a low growl to rekindle her anger. ‘How could you let us bury my sister without her heart? How could you be so insensitive? What do you think Mum will say when she hears about this?’ Áróra gave a gasp. ‘She mustn’t find out. It would destroy her.’ She grabbed Daníel’s arm. ‘You mustn’t tell her!’

Daníel looked at her, saddened. ‘Your mum knows about it,’ he said calmly. ‘Gutti told her as soon as we found out.’ 12

‘What?’ Áróra gazed at him in astonishment. ‘What…? How…?’ She didn’t even know which question to ask first. Her mind was a jumble of senseless thoughts.

‘Your mum didn’t want us to tell you,’ Daníel said. ‘She didn’t want you to suffer. And as Ísafold’s closest relative it was her decision to make.’

Áróra felt a flash of annoyance towards her mother, before realising how silly that was. Only a moment ago, she had implored Daníel to spare her mother by withholding the same information from her.

‘Your mum was convinced you’d get the bit between your teeth and refuse to bury her until we’d found her heart,’ Daníel went on. ‘She also felt you both needed some kind of closure. Time to say your farewells.’

Áróra stared at him and a sense of unease crept over her. This wasn’t over. This was far from being over. Not only had they yet to find Ísafold’s killer. They also had to find part of her body. Ísafold wasn’t whole where she lay buried in the ground next to their father.

‘And … and, what? Now you’re looking for her heart?’

‘I think that has to be in the mix, yes,’ Daníel said. ‘Although our decision to bury Ísafold’s body as it was found, in consultation with your mum, was based on the fact that we may never find her heart.’

‘How can you know that?’ Áróra was shouting again.

‘We can’t,’ Daníel replied calmly. ‘We’ll have to wait and see whether any clues emerge in the course of the investigation. This is still a cold case, even though it’s only been a few weeks since we found the bodies.’

‘Six weeks ago,’ she said. ‘You found them six weeks ago.’

‘Yes,’ Daníel replied softly, looking at her in a way that told her he was trying to read her thoughts.

‘Stop it,’ she said. 13

‘Stop what?’ he asked.

‘Looking at me like that.’

He averted his eyes, and she wanted to shake him. She wanted to go on being angry, to shout and scold him, but she couldn’t. She’d never been able to stay angry with him for long.

‘Shall I drop you off at home, so you can rest for a while, collect yourself?’ Daníel asked.

But Áróra shook her head. ‘No,’ she replied, and strode off. ‘I’m going to The Gym to lift a hundred kilos.’

6

Ísafold gasped for breath on her way up the stairs, and felt her heart pounding in her chest. It wasn’t due to the physical effort of walking up one floor but because the fear she felt had sent her entire body into a panic. She’d bedded down in the bathroom that night, rolling up a towel for a pillow and spreading her bathrobe over her. This had enabled her to drop off at intervals, when the pain didn’t waken her, or some rustling sound startle her. Björn, on the other hand, seemed to have gone out like a light, and she hadn’t heard him stir all night. So, at about eight in the morning, she had cautiously unlocked the bathroom door, and crept out without making a sound. Hearing Björn’s snores coming from the front room, she counted her blessings, as it meant she could sneak into the bedroom to fetch some clothes. Turtleneck tops had become an essential item of clothing, and she had bought several in different colours with necks high enough to conceal finger marks or love bites. Depending on the circumstances.

She’d managed to slip out without waking Björn, and as work had been busy that day, she’d had plenty of other things to occupy her – a good many customers as well as a delivery that needed to be unloaded, inventoried and the clothes put on display. But now, as she forced herself to mount the stairs, one by one, panting like a pack animal, she was gripped with fear. If Björn was still drinking and seemed irritable, the best thing would be for her to turn around and try to leave straight away. Maybe she could stay with Björn’s brother, Ebbi, or find a cheap hotel for the night. When Björn was like this, his bad mood usually lasted until he stopped drinking, then as the alcohol wore off his anger subsided.

She turned the key in the lock and walked calmly inside.

The radio was on in the kitchen and she could hear the clatter of pans.15

‘Hi, sweetheart,’ Björn called as he peered out, a cheerful look on his face, as if yesterday evening had simply been a bad nightmare that had only taken place in her head.

‘Hi?’ She heard the questioning tone in her own greeting, as if she was testing his mood with her tentative hi. To see whether it was safe for her to be there.

‘I’m cooking lasagne,’ he called out, and she heaved a sigh. It seemed everything would be all right. Björn was no doubt hungover, and while that state lasted, he was often affectionate. It was safe for her to go in. She slipped off her parka and placed it on a hanger, then hooked her handbag round the neck of the hanger, which she always did, so she could grab what she needed in the event she had to flee. She walked slowly into the kitchen and was relieved to see Björn sipping a can of Coke while he cooked. ‘I was thinking maybe we could rent a movie and eat our dinner in front of the TV,’ he said, and for an instant Ísafold doubted whether yesterday evening had been as bad as she remembered. Had she blown what happened out of all proportion in her mind? Had Björn really tried to strangle her?

‘Don’t we need to talk first?’ she asked softly, and he sighed.

‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘Of course. I promise, no more booze in the near future.’

‘It’s not just that, Björn,’ she said. ‘You were so awful yesterday. I was terrified of you.’ She felt her pulse quicken. There, she’d said it now, and she hardly dared breathe for fear of how he might react. But he didn’t go crazy, nor did he laugh. He simply stared at her, with a look that suggested she’d said something hurtful. Then he walked up to her, and she recoiled instinctively, even though he seemed on the brink of tears. He stretched out his hand and drew her to him.

‘Sweetheart,’ he whispered, placing his arms about her.

It took Ísafold a while to relax in his embrace, to allow him to clasp her body against his, pull down the neck of her top and kiss her throat.16

‘Forgive me,’ he whispered. ‘I don’t know what the hell’s wrong with me. I love you so much.’ His voice was quaking, his breath ragged, as if he were sobbing.

He sounded sincere, and Ísafold felt her defences melt away. Maybe yesterday had been bad enough to bring him to his senses? Maybe everything would be okay?

7

Áróra had almost reached The Gym when she decided to turn around and drive up to Kópavogur instead. Her heart was pounding so fast that the curious notion occurred to her that somehow it was beating for both her and Ísafold, and if she put too much strain on it, it would simply burst.

She felt she needed a foothold, some solid foundation to stand on, because earlier at the police station it was as if the rug had been pulled out from under her feet. As if everything she’d so far concluded about Ísafold’s disappearance and death had been wrong, and something quite different had happened from what both she and the police had believed.

The block on Engihjalli towered above Áróra as she crossed the car park on her way to the entrance. The cluster of blocks perched on the crest of the hill like lighthouses, offering splendid views to residents whose apartments faced the right way. Björn and Ísafold’s apartment didn’t. It overlooked an industrial estate, with the blue sign of a builder’s merchant in the foreground. Ísafold had always maintained she was living her dream life, which Áróra found strange, because for her the good life had a completely different meaning. But Ísafold insisted her dream had always been to live in Iceland, speak the language again, as well as she had when she was a kid, and adopt the Icelandic way of life. Áróra had never experienced this powerful need to feel connected to Iceland. Not until her sister disappeared.

The tower block seemed to trap the wind and funnel it downward, so Áróra found herself standing in a cold draught. She shivered, pulled her coat about her and pressed Olga’s buzzer. Olga was a fellow resident in the block who had been kind to Ísafold, and was apparently one of the few of her and Björn’s 18neighbours who still lived there. Áróra pressed the buzzer again, but no one replied. She was probably still at work. As she pressed the buzzer a third time, she heard a noise in the stairwell and saw through the glass that someone was coming down.

The door opened slowly and Áróra found herself face to face with Grímur, the other neighbour of Ísafold’s she knew. Apparently, he’d come down to fetch his post and was surprised to see Áróra there.

‘You’re so like her,’ was the first thing he said, and Áróra smiled. She’d always found Grímur strange. Felt a bit sorry for him. He seemed to suffer from some skin disease, as he was completely bald with no eyebrows, and his skin was red and puffy. More than once, however, when Björn went berserk, he’d helped Ísafold, and Ísafold had always referred to Grímur as her friend.

‘How are you?’ Áróra asked, and Grímur opened his mouth, hesitated then stammered:

‘Not so bad.’

He didn’t ask her anything in return, simply stood and looked searchingly at Áróra until she explained she’d been trying Olga’s buzzer.

‘Olga’s not here at the moment, she’s on holiday in Canada,’ he said.

‘Canada?’ she repeated, and for an instant it was as if her thoughts came to a halt when confronted with this fact, and became stuck in some rut that wouldn’t let her advance.

‘Is there a particular reason why you wanted to see her?’ Grímur asked, jolting Áróra’s thoughts back into motion.

‘No,’ she replied. ‘Nothing special. Just to have a chat with her, ask her if she remembered anything else about Ísafold.’ Gutti had insisted she keep quiet about new information relating to the case. She mustn’t tell a soul about this thing with the heart. So, she prevaricated. ‘Now the investigation is back on track, I felt I had to do something. Be connected with the case in some way.’ 19

‘They’ve resumed the investigation?’ Grímur seemed surprised.

‘Yes. You know they found my sister’s body?’ she said. ‘Both their bodies.’

‘Indeed. Altogether very strange,’ he said. ‘Putting them in suitcases like that.’

Áróra nodded, and, not wishing to think about suitcases, about bodies stuffed into suitcases, she added: ‘Well, then,’ and made as if to leave. But then she remembered something else. ‘Do you know who’s living there now – in their old apartment?’ She indicated the slot next to the buzzer, from which the card with her sister’s and Björn’s names had been removed.

‘It’s empty, has been ever since,’ Grímur said.

‘Really?’ Áróra found this odd.

‘Yes,’ said Grímur. ‘Björn’s family only just cleared the apartment. They plan to put it up for sale. I gather it’s a lengthy process to have a missing person pronounced dead. And for a long time Björn’s mother believed her son would come back, so she held on to the place.’

‘I see.’ For the first time Áróra’s felt sympathy for Björn’s mother. In reality, she’d been in the same position as Áróra and her mother – suspended in uncertainty. Áróra had long condemned her for not having helped Ísafold. For refusing to acknowledge her son’s violent character.

‘I have the key if you want,’ Grímur said then. ‘Ísafold gave it to me once, and I kept it. So, if you want to go inside and take a look around, this could be your last chance before someone moves in.’

Áróra followed Grímur back up the stairs to his apartment where he slipped through the half-open door, indicating that he wanted her to remain outside while he fetched the key. Then she followed him up to the floor above and waited while he struggled to insert the key into the lock, his hand trembling. He 20stepped aside to let her go in first then entered the empty apartment behind her. They both came to a halt in the living room and stood silently for a while. For an instant, Áróra felt as if she had some connection with Ísafold, as if this room that had remained closed to the outside world for so long retained in its dusty walls some clue to her sister’s final days.

The sensation quickly evaporated, and Áróra walked over to the window and looked out at the timber yard of the builder’s merchant. Then, for some reason, she recalled what had made her thoughts stall just now. Canada.

8

Daníel frowned and rubbed his forehead. A drowsy feeling crept over him as he sat facing Ari Benz Liu, chief superintendent at the International Department of the Police Commissioner’s Office, listening to him ramble on, the way he always did when he couldn’t, or wouldn’t, be straight with someone.

‘This is a collaborative project,’ Ari said. ‘So, obviously, when Europol asks us for information, we comply.’

Daníel nodded glumly. ‘Yet when it comes to explaining why they want the information they aren’t forthcoming,’ he retorted.

Ari grinned. ‘No. They’re the big chiefs. What I can tell you, off the record, is that I think it’s linked to a big international money-laundering operation.’

Daníel heaved a sigh. He doubted he could wriggle out of this one, but he’d give it his best shot.

‘You know how much financial crime bores me,’ he muttered, and Ari laughed out loud, as if to make light of the whole matter.

‘You can’t have a murder every day,’ he said with a smile. ‘Besides, your boss tells me you’re available. And, of course, your partner being an expert on financial crime makes you the perfect candidate. Come on, Daníel. We’re talking two or three days here. By the weekend you’ll probably have some brand-new violent crime to investigate. But until then, please do me this one favour!’ Ari pouted and made puppy eyes at Daníel, who burst out laughing.