Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

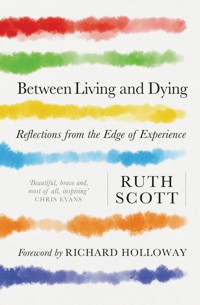

Busy and deeply absorbed in all the complexity of life, Ruth Scott's packed diary suddenly had to be cleared when she was diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer. She said, 'Discovering that life might be shorter than expected or hoped for concentrates the mind wonderfully. Whatever life is left to me, I do not want to waste it.' In the final months of her life, in the shadows between living and dying, she learned to live with the extremes of treatments that were as aggressive as the disease - and with daily ups and downs that created constant uncertainty. Throughout it all, Ruth creatively explored - through insight, literature, poetry and song - what life is about and how it should be lived. This book is the result. Here, she cuts through all the things in life that we waste our energies on. She explores the depth of life in ways that allow for doubt, absence and uncertainty while also making room for mystery and understanding beyond rational limitations. As she reflects on how we relate (or not) to each other, to the environment and to the 'more-than-me-ness' of life, she offers real inspiration for us all.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 278

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BETWEENLIVINGAND DYING

First published in 2019 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © the Estate of Ruth Scott 2019

Foreword copyright © Richard Holloway 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78885 224 1

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Gutenberg Press, Malta

For Mairéadwith gratitude beyond words

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

1 Living with uncertainty

2 Making space

3 Losing control

4 Facing our fears

5 Who am I?

6 Separate and shared storylines

7 To be or not to be . . .

8 Hitting the depths

9 Now what?

10 ‘See, you are well! . . . possibly

Epilogue

Two additional poems

Afterword

Notes

Copyright acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

I owe my heartfelt thanks to a number of the teams at Southampton General Hospital, but particularly the lymphoma team under the leadership of Prof. Peter Johnson, Prof. Andy Davies and Dr Rob Lown. They, their registrars, junior doctors and specialist nurses have cared for me throughout the whole process of writing this book. They may not share the views expressed in these pages but their expertise and compassion enabled me to progress through treatment in the best possible state of mind and body and, as a result, to write about the experience and the reflections it provoked. Much of the book was written while I was an inpatient on D3, the Oncology ward. I was there for many months and felt utterly safe in the care of the nurses, health-care assistants, cleaners and caterers who became like family. Thanks, too, to Dr Andrew Jenks, who has kept me sufficiently pain-free to keep writing when the going got tough.

Mairéad, my specialist nurse, has been my constant guide. She has pulled me through. Without the trust I felt in her, I would not have had the energy to start writing in the first place. No one could have done more than she has.

My beloved Chris has been my strength and stay. Freya and Tian have continually inspired me. My wonderful friends have produced the images, poems, books, and constant affirmations of love that have given shape to this book. I’m especially grateful to Richard and Alison who provided words of comfort in the dark watches, and to Richard for believing I was writing a publishable book. Thank you for having faith in me and opening doors.

I’m grateful to Sue for correcting the grammar and punctuation of the first draft, and making helpful suggestions.

Thank you to Ann Crawford and all the team at Birlinn, especially for going above and beyond the call of duty when illness meant I could not fulfil all my responsibilities in seeking permissions. Your patience and kindness has meant a great deal.

Lastly, I thank all those women, alive and dead, named and unnamed, whose cancer treatment coincided with my own. Thank you for your song lines. They gave me strength and courage.

Foreword

When apprentice radio presenters are nervously trying to learn the craft of broadcasting, they will sometimes be counselled by veteran producers about how to do it. They are told there are two lessons they have to learn. The first is, get out of your own way, forget yourself, don’t watch yourself doing this. And next, talk to the ear not to the audience. You are not addressing a multitude. You are speaking to an individual. It’s all between you and another human being. Good radio broadcasters know how to keep it close and personal.

While some of this can be learned, I suspect that the best broadcasters have an instinct for it. It’s what has been described as ‘an original endowment of the self’. A gift. In Greek, a charism. That was certainly how it was with Ruth Scott during the twenty-three years she did Pause for Thought on BBC Radio 2, first with Terry Wogan, then with Chris Evans when he took over. Ruth was a charismatic broadcaster. Listeners felt she was beside them, speaking from heart to heart. And it wasn’t a trick she had learned; a practised intimacy; an act. It was who she was. Ruth had the gift of presence, of being there for others.

A magnificent example of this was her final broadcast, when Chris Evans interviewed her in Southampton General Hospital only weeks before her death. It was no surprise that a podcast of the interview went viral. It was a not-quite-last gift to the countless people who had been nourished by her wisdom over the years. She spoke calmly of what it felt like to know that death was on its way to take her from a life that had been filled with love and achievement; a life she was sorry to leave so early; a life she was grateful for having lived.

It was characteristic of her that, not content to die well, enfolded in the love of family and friends, she wanted to observe and interrogate her own dying to find out what it might teach her and others. That’s why she told Chris that during the first year of her chemotherapy she decided to write about her experiences. And this beautiful book – her last gift to us – is the result.

This is how she described what she was doing: ‘As I write this book, I’m receiving intensive chemotherapy for a rare and aggressive cancer, an enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, and, further down the line, the plan is for a stem cell transplant. The aim is cure, but it’s not guaranteed. If all goes according to plan, it will be a year between the start of my illness and the time I may be well enough to return to work: a gap year in the shadow of death’. Sadly, there was to be no cure, no return to work. Ruth died on 20 February 2019.

Ruth was many things in her life: loving wife and mother, friend, priest, athlete, broadcaster, conflict resolver, writer. But above all, she was a nurturer, a healer. She had come to London aged eighteen to train as a nurse, and that background shows in the professional attention she brought to the treatment she received in hospital, as well as in her warmth towards the doctors and nurses who ministered to her. That’s why this book is not for the faint-hearted. In these pages you will read vivid descriptions of her treatment and its consequences – and the humour that often attended both. It is a wrenching read, but it is also funny and affectionate. And it is a magnificent tribute to Britain’s National Health Service and the people who make it work, often against incredible odds.

But it is much more than that. That’s because Ruth Scott was a teacher as well as a healer. And she wanted to learn from what was happening to her. She said she wanted her book to be ‘a meditation on life, not death, offering observations and asking questions that have occurred to me through this gap year’.

The first lesson she learned was personal: to let go of control. Then the philosopher kicked in, and she began to wonder if her cancer wasn’t a metaphor for what is happening in the human community today. She informs us that cancer cells are ‘ordinary cells that go into division overdrive, producing more and more of themselves, becoming distorted in the process and destructive to the body to which they belong’. A perfect metaphor for the human condition. It was this tragic divisiveness in the world that had prompted Ruth to become a mediator and facilitator in the field of conflict resolution, a role that took her into many dangerous and violent places.

The mediator is at work in this book too. She advises us in situations of conflict to articulate our concerns and grievances. Well, most of us are good at that. We fill the land with our noisy protestations. Much more difficult is listening to the other side. Here she invites us to prepare arguments ‘supporting the view with which we most strongly disagree’. Reading that challenged me to interrogate my own compulsions. When I hear someone expounding a point of view with which I vehemently disagree, I am rarely listening: I am preparing my counter-blast, ramming shells into my biggest guns. Thank you, Ruth, for disarming me.

But there’s more. She tells us that what most people find difficult is not change as such, but loss. Another gift. This book is full of them. Sip it slowly.

As well as her own wise teaching, another richness of this book is the wealth of quotations from poets and other writers Ruth uses to illuminate her reflections. One of them is from Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient:

We die containing a richness of lovers and tribes, tastes we have swallowed, bodies we have plunged into and swum up as if rivers of wisdom, characters we have climbed into as if trees, fears we have hidden in as if caves. I wish for all this to be marked on my body when I am dead. I believe in such cartography . . .

Ruth Scott is gone, but she has left us a map to guide us through our own lives.

Richard Holloway

July 2019

Edinburgh

Introduction

Apart from a short lull in the early morning, there are always ambulances coming and going beneath my window. All life is there: babies barely visible under the plethora of intensive care tubes and monitors; elderly men and women swathed in blankets; anxious relatives trailing behind the trolleys. The walking wounded of all ages and, of course, those made stupid with drink shouting out their fury against the ambulance personnel seeking to help them and the police called in to constrain them. All have been brought here for treatment that will diagnose, cure or contain their illnesses and injuries, or take them down the road to end-of-life care. A few days ago I was one of them, transferred from the emergency treatment I needed in my local casualty department to the Oncology ward in the teaching hospital where I’ve been receiving ongoing care.

As I write this book I’m receiving intensive chemotherapy for a rare and aggressive cancer, an enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, and, further down the line, the plan is for a stem cell transplant. The aim is cure, but it’s not guaranteed. If all goes according to plan, it will be a year between the start of my illness and the time I may be well enough to return to work: a gap year in the shadow of death.

In the middle of the night, when the ambulances’ reversing alarms shatter the silence, it is not death which preoccupies my mind but life, and what I do or don’t make of it. Have I been awake or sleepwalking through it, thoughtlessly going through the motions, or relentlessly impelled on by internal drives I think I understand but never quite manage to harness more creatively? The valley of the shadow of death is a thought-provoking place in which to consider human experience, my own and others’. Sitting by my window overlooking the ambulances while my chemotherapy drugs drip through the intravenous line, I have time to reflect on what has been, what is and, should I live to tell the tale, what might be. So-called normal life looks very different from the perspective of this vale.

I wonder at times if my cancer is a metaphor for what’s happening in our present culture: put simply, cancer cells are ordinary cells that go into division overdrive, reproducing more and more of themselves, becoming distorted in the process and destructive to the body to which they belong. It seems my immune responses have lost their capacity to recognise and deal with cancer cells. This micro-dynamic appears replicated in relation to how we function on a wider scale. All around me I see people whose lives are distorted by profound stress as they struggle to address the destructive fallout of a pace of life over which they feel they have little control. It’s not a new phenomenon. In every age there are those who fall by the wayside in the struggle to survive. What is unique to our present experience is the speed and impact of scientific and technical change. Even positive developments require periods of adjustment. We have access to more information than we can process, and the lack of time and opportunity for careful reflection as we rush headlong into the future stirs up a whirlwind of conditions and consequences that are creating divisive conflict, as well as unjust and unsustainable expectations of humankind and the earth which has nurtured us thus far.

That’s why this book is a meditation on life, not death, offering observations and asking questions that have occurred to me through this gap year away from the ‘everyday’, and sharing the insights of those who have inspired me along the way. Right from the start of this journey I decided to read any books, essays, papers, poems or quotations that friends gave or recommended to me. I have included some but not all of the poems that have been meaningful to me through this time. At the end of the book, I have added notes on three poems that touched me but could not be included. It was a delight to find, so often, that the poetry and prose that came my way during treatment was relevant to chapters I was writing at the time.

This is not a systematic, academic treatise, although I hope it is intelligent in expression. Life is messy and complicated and I have never found my thinking neatly ordered. In this book I explore different aspects of human experience that have arisen during treatment. In that process I have become aware of an over-arching theme of separation, the disconnection we experience within ourselves, from others and from the wider environment. As I’ve gone along I’ve raised questions about what we accept as normal life and wondered about the need to do things differently.

When I was first diagnosed, as a means of feeling I had some control in the situation, I was keen to see treatment as a pilgrimage, something from which I would learn much. The first lesson, as it turned out, was an essential learning to let go of control, of not having to make something good out of something bad, of not trying to grasp the reins steering this crazy horse of cancer. Unexpectedly I had an ‘Ah yes!’ moment when my friend, Melanie, sent me a verse from St Paul’s letter to the Romans. I am not a fan of people quoting scripture at me. Too often such quotes are taken wildly out of context and have been used more as bullets to destroy perceived heresy, rather than to build bridges of understanding, but that’s not Melanie, and her choice of verse was spot on:

Likewise the Spirit helps us in our weakness; for we do not know how to pray as we ought; but that very Spirit intercedes with sighs too deep for words.1

I felt in those words my degree of unwellness was recognised, as was the depth of its impact upon me. Most importantly, they left me feeling speech wasn’t necessary and I hadn’t got to resolve it all, but simply live through it. Others would hold it for me. It was a call to stop trying, to simply ‘be’, and to not feel so responsible. This is hard to articulate because it was not about being irresponsible, or not playing my part. It was more about relinquishing the sense of being driven and the toll that it has taken on who I am. What a relief! In the early weeks after the diagnosis I was able to let go of the pressure I’ve always placed upon myself, consciously or unconsciously, to achieve. Paradoxically, the thoughts that gradually began to emerge as I gave up on the need to ‘make something of all this’ came unforced into my mind and naturally began to form themselves into the words you’re now reading. At that point, whether or not they became a book wasn’t my priority. It was just a helpful way to pass the time in my hospital side-room when I had the capacity to concentrate. For this reason I had no structure in mind when I started writing, and much of it is written in the present tense.

I became ill at Christmas 2016, wrote most of this book during my hospital admissions in 2017, added the epilogue after complications arising in 2018, and completed editing just before Christmas 2018. The first draft ended up in a mix of present and past tenses, depending on whether I was writing up what was happening at the time or reflecting back on it. This was sometimes confusing for my initial readers. In response, apart from in this introduction, I have put most of my hospital narrative into the past tense. While the book begins and ends with the personal experiences that began and ended the time covered by the book, other illustrations from my treatment with which I open the intervening chapters are not always in chronological order. This is because, in the editing, it made more sense to make the order of themes explored the priority.

In the same way that cancer enabled me to relinquish the pressure I placed on myself to achieve, it also released me from what might be considered more overtly religious responses to my situation. I became ill not long after we moved to a new home in a new place, so I was not familiar with the priests and people at the cathedral, nor the lovely folk at the Quaker meeting I started attending. All were immensely generous in their offering of support, but I knew the people I wanted around me at this time were family, close friends and the lymphoma team. Formal church liturgies in their length and wordiness became an irrelevant endurance test I was unwilling to undergo.

To make the cancer diagnosis it was necessary to operate on my small intestine to gain biopsies of the lymphoma tissue. While recovering from this surgery I discovered the hospital chapel. It was a wonderful place to sit contemplatively alone by its water feature and greenery. I attended one Sunday service but didn’t want to repeat that experience because it felt meaningless. The Baptist chaplain came by, early on in my long hospital stays. I enjoyed seeing him and was moved that when he offered to pray at the end of his first visit and I declined, saying I felt more comfortable with silence, he was willing to be silent with me. I felt no need for overt religious practice. I guess that was part of the letting-go and seeing what, if anything, emerged. I wasn’t interested in the platitudes and simplistic understanding of suffering that some people of faith offered me.

I was grateful for all the people, known and unknown to me, that I knew were praying for me, and uplifted by the positive energy I think prayer creates, but I cannot accept an image of a God who heals me because people pray for that, while leaving millions of others to suffer. When someone offers to pray for me I want to know what they think they are doing.

Living with cancer makes me understand more of ‘prayer’ as the spontaneous utterances, inspirations and moments of awareness that well up within us and between us, and give shape to our deepest being. Prayer may arise in anguished or ecstatic souls, and often looks nothing like the formulaic recitations that tend to bear its name. I know many friends who find comfort and strength in the daily discipline of saying Morning and Evening Prayer, but it is not how I choose to pray. There are so many words, many of the sentiments of which I have ceased to believe. For the most part I have come to see prayer primarily as lived experience, not set words. Carol Ann Duffy captures this beautifully in her poem ‘Prayer’:

Some days, although we cannot pray, a prayer

utters itself. So, a woman will lift

her head from the sieve of her hands and stare

at the minims sung by a tree, a sudden gift.

Some nights, although we are faithless, the truth

enters our hearts, that small familiar pain;

then a man will stand stock-still, hearing his youth

in the distant Latin chanting of a train.

Pray for us now. Grade 1 piano scales

console the lodger looking out across

a Midlands town. Then dusk, and someone calls

a child’s name as though they name their loss.

Darkness outside. Inside, the radio’s prayer –

Rockall. Malin. Dogger. Finisterre.2

Ah, the shipping forecast! Who would have seen that as a mantra? Yet to my friend Paulie, who had loved listening to the shipping forecast for as long as he could remember, it was a source of comfort as he lay dying of an inoperable cancer.

From Scotland, my dear friend Alison sent me the photo of a tile with fishing boats and their home ports named upon it and, as I savoured the names of the boats in my hospital bed, I was transported to harbours and high seas and a sense of wildness and strength and freedom. The boats were:

The Rose of Appledore

The Welcome of Freckleton

The Flying Foam of Bridgwater

The Gleaner of Runcorn

The First Fruits of Bridport

Another friend, Rachel, always brought images of the Isle of Iona, one of my favourite settings, so I could take myself there for a while in my imagination, and feel the healing power of that place. Other friends sent photos of beautiful objects, places or paintings. They were surprise gifts bringing light into the darker times when the side-effects of treatment were tough. That’s why letting go of control and how I live normally has been so important for me, because wisdom often turns out to be where I don’t expect it, prayer emerges when I don’t try to make it, and life reveals so much more when I don’t think I’ve got it all sewn up, particularly, it seems, in the valley of the shadow of death.

1

Living with uncertainty

In Greek mythology the River Styx is the boundary between the living world and the land of the dead, Hades. Few people cross it and return. None of those who do come back are unchanged by what is often a bruising experience. In all the great myths of the major world faith traditions, rivers, like mountains, deserts and seas, are liminal spaces marking the change from one way of being to another, sometimes with the reality of personal mortality needing to be faced so that it is no longer feared.

In the months after my diagnosis, I did not literally go into the land of the dead, just the valley of the shadow of death, though many of the new friends with cancer with whom I shared the journey died: Mary, Rosie, Ann, Grace, Sylvia, Sonya, Carol . . . the list of women who touched me with their quiet courage and unobtrusive kindness and compassion goes on. We sat quietly with one another through nights when the pain was crippling, acted as gofers when one or other of us was less mobile, provided shoulders to cry on and provoked laughter in one another at the undignified moments, moments when enemas were more explosive than expected, or the shower room became an assault course of all our bedpans of wee waiting to be measured and tested by staff rushed off their feet and too stretched to collect them.

My own personal version of the Styx is a corridor in my local hospital. On one side is the doctors’ consulting room, and on the other, the dayroom of the Medical Assessment ward. It was in the doctors’ room one afternoon at the end of March 2017 that a young house doctor told me that the CT scan I’d had a couple of hours earlier showed changes in my small intestine consistent with lymphoma. It was the first time that concrete evidence existed for the diagnosis I had suspected for some months. I was strangely relieved.

The doctor wanted to move swiftly to get biopsies, and so she asked if I would stay to be admitted to the Medical Assessment ward. As an inpatient, there was a higher chance that I could get on to the endoscopy list for the next day, and have biopsies taken. It meant sitting in the corridor for a couple of hours until a bed became available. No problem, I said. Chris, my husband, stayed for an hour, but, eventually, I suggested that he went home. I was fine, and there was no point in two of us waiting. I became less fine as two hours turned to four, then six, then eight. A draughty corridor was not the place to sit alone as the reality of a life-threatening diagnosis sank in, but, finally, nine hours later, I made it into the ward dayroom, and an hour after that, at midnight, a bed was ready for me.

That corridor marked the transition for me between normal life and the valley of the shadow of death. Some people describe the change between the time when everything in their lives is fine and the sudden experience of trauma or tragedy as taking them into a parallel universe where nothing is familiar. In the early days of being in this unfamiliar territory, an image used by Teilhard de Chardin, the French philosopher and Jesuit priest, captured for me this profound sense of dislocation. He wrote of those moments when we ‘lose all foothold within ourselves’.1 For him this is a state to be actively sought so that we become the space into which God may come but, in my experience, deep trauma may also impose upon us this loss of self. Since it is unlooked-for, there is no guarantee that anything we might describe as divine will infuse the emptiness. A friend whose son was killed in a tragic accident identified profoundly with a dead fox she found one day by the side of the road, snuffed out in an instant by a passing car. Like the fox, with the cars hurtling past its lifeless body, she felt dead inside while life continued as usual around her. She was no longer part of it. Human existence looks different for people who suddenly find themselves confronted by their own mortality or that of the people they love. It’s not that this isn’t life just as much as so-called normal life may be, but it is qualitatively different.

Later in my treatment, my friend Marion sent me two postcards, both self-portraits by Rembrandt. One was a sketchy black and white etching; the other a full-blown oil painting. Marion thought the sketchy image was like my life in the shadow of death and the oil painting was like my normal life. I wasn’t so sure. It’s true that, with life-threatening illness, the illusion of security with which many of us live disappears and existence suddenly appears very fragile and ‘sketchy’. But, although living with cancer seemingly narrowed my life considerably, it also brought an unexpected richness and depth of insight. My priorities changed. I came to see things differently and was glad of the experience.

During a rare few days out of hospital in the middle of treatment, I sat in the Quaker Meeting for Worship where I’m a member and became completely absorbed in the windows. I was struck by how, where the sunlight hit the glass, they were impossible to see through because of the smearing being illuminated – but where the wisteria leaves cast their shadow on the panes I could see clearly through the glass. The image seemed to connect with my experience: in the shadow of death, vision becomes clearer. The abnormalities of normal life are thrown into sharp relief. The extra-ordinary landscape of life-threatening human experiences – in my case, this rare and aggressive cancer requiring surgery, intensive chemotherapy and stem cell transplant – became the ordinary everyday for the duration, while to those looking on from normal life it remained shocking and difficult to accept.

The hard part was moving between normal life and the valley of shadow. I noticed that on the days when I was in good shape for the state I was in, perhaps having enjoyed an ordinary activity like walking into town and feeling very much in the land of the living, I was utterly thrown by catching sight of my bald head and the permanent IV line in my arm reflected in a shop window. I needed those occasional days of normal life, but they were unsettling as well when the reality of being seriously ill intruded into them. I’ll say more about this later in the chapter.

A number of friends said how unfair it was that I had cancer, but I’ve never felt that. Life happens. We are the product of all the generations that have gone before us, the genetic inheritances, the times and places in which we live, the experiences of joy and grief we have. Why not me? I certainly don’t believe in a God who would give me this suffering. I simply see it as life evolving in all its creative and destructive complexity as it has from the time of the Big Bang. Through treatment, my infinitesimally small part in that story concerned how I chose to respond to the unexpected development of cancer. My international working life, lived at high speed, shrank to playing my part as positively as I was able in getting me well, if that was possible. My achievements, if such they were, changed. Before my diagnosis I had worked with the casualties of violent conflict around the world in trauma care or peace-building; I had talked to millions on the radio; run retreats and workshops around the country. Now, I was rejoicing, as on one particular day after abdominal surgery, at being able simply to pass wind! Such things require a radical shift in thinking, often a change in how we understand ourselves and our worth as human beings.

When I first became ill, in December 2016, I was coughing and struggling to breathe, waking with night sweats and spiking temperatures. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, then pulmonary embolism and pleurisy all came up as potential diagnoses. Blood tests confirmed something wasn’t right, but working out what it was took longer. In January, I looked up my symptoms on the internet. Lymphoma emerged as a possibility, but the evidence needed to confirm that diagnosis didn’t come easily. A gastroscopy and colonoscopy showed nothing (because neither endoscopy could reach the bit of intestine where my cancer had produced lesions). I was thrown by the results. I should have been glad no problem was revealed, but I knew how ill I was becoming, and the spectre of childhood experience – when I’d been unwell but not believed – rattled my equilibrium. What if the doctors didn’t believe me now? Reality indicated that they knew well enough that something was not right and that my fear of not being taken seriously was irrational. It’s not uncommon for the vulnerability of illness to highlight the raw points in our psyches as well as plugging into our strengths.

For three months, I visited my GP surgery more times than I had done in my whole life before. I was always referred on to the local hospital. I lost a lot of weight. I carried on working while recognising that I was becoming more and more unwell. One evening, after a couple of days co-facilitating a difficult conversation for a group in London, I set off for home. As I packed the car and drove away, abdominal pain kicked in, making it hard to breathe normally. I felt really cold and couldn’t get the car warm enough. The motorway I needed was closed and traffic had backed up for miles. Eventually I took a diversionary route, set the SatNav, but missed a vital turning. A two-hour journey took four hours. Ten miles from home, on a B road in the middle of goodness-knows-where, pins and needles started in my hands. I pulled off the road and began to get out of the car but that made me dizzy and I fell back inside. The pins and needles spread to my legs. I wondered if I was having a stroke. I lay there calming myself until the symptoms passed. Eventually, I was able to get out and walk around a little before setting off again. By the time I got home, I was shivering uncontrollably. My temperature was very high and I felt wretched. The next day, I woke up feeling fine and carried on. Eventually, however, the symptoms began to affect my concentration at work and the need for further investigations, including diagnostic surgery, was apparent. At the end of March, after the diagnosis, I realised I could no longer keep going as I was. Reluctantly, I cleared my diary.