Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

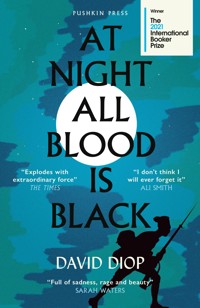

FINALIST FOR THE 2023 NATIONAL BOOK AWARD FOR TRANSLATED FICTION 'Stunningly realized... A spellbinding novel' MAAZA MENGISTE, Booker Prize-shortlisted author of The Shadow King'Diop has opened a new way of thinking about the eighteenth century and its hideous cruelties' ABDULRAZAK GURNAH, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature'A compelling romantic adventure... Through an act of remembrance, Diop seeks to build a repository of lives and histories lost to the slave trade' FINANCIAL TIMES __________ The captivating new novel from David Diop, winner of the International Booker Prize Paris, 1806. Michel Adanson is dying. The last word to escape his lips is a woman's name: Maram. Who was she? Why, in the course of his long life, has he never spoken of her before? As Adanson's daughter sorts through his things, she discovers a notebook. It reveals a secret history both fantastical and terrible, of his time as a young botanist travelling in Senegal. How Adanson first heard of the 'revenant': a young woman of noble birth, abducted and sold into slavery across the seas, who then did the impossible-she came back, to live in hiding. How he became obsessed with finding her, embarking on an odyssey that would lead to danger and destruction. How a man who longed to solve the mysteries of nature instead found himself faced with the uncontrollable impulses of the human heart. Tragic and tender, alive with feeling, this is a story of adventure, revenge and impossible desires, one which subverts our every expectation about who we are and who we love.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 323

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

praise for

Winner of the International Booker Prize

Winner of the LA Times Book Prize for fiction (USA)

Winner of the Prix Goncourt des Lycéens (France)

Winner of the Premio Strega Europeo (Italy)

Winner of the Europese Literatuurpijs (Netherlands)

Winner of the Prix Ahmadou-Kourouma (Switzerland)

“So incantatory and visceral I don’t think I’ll ever forget it”

ali smith

“Extraordinary… Full of sadness, rage and beauty”

sarah waters

“A great new African writer”

chigozie obioma

“A stunning book for our times”

philippe sands

BEYOND THE DOOR OF NO RETURN

DAVID DIOP

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY SAM TAYLOR

PUSHKIN PRESS

To my wife: I weave these words for you and your silky laughter.

To my beloved children, and to their dreams.

To my parents, messengers of wisdom.

Eurydice—Mais, par ta main ma main n’est plus pressée!

Quoi, tu fuis ces regards que tu chérissais tant!

Eurydice—But my hand by yours is no longer held tight!

Why do you flee my eyes which you once loved so?

—Gluck, Orpheus and Eurydice (Libretto translated from German to French by Pierre-Louis Moline for the premiere on August 2, 1774, at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal in Paris)

CONTENTS

BEYOND THE DOOR OF NO RETURN

I

Michel Adanson watched himself die under his daughter’s gaze. He was wasting away, racked by thirst. His joints were like fossilized shells of bone, calcified and immobile. Twisted like the shoots of vines, they tormented him in silence. He thought he could hear his organs failing one after another. The crackling noise in his head, heralding his end, reminded him of the first faint noises made by the bushfire he’d lit one evening more than fifty years before on a bank of the Senegal River. He’d had to quickly take refuge in a dugout canoe, from where—accompanied by the laptots, his guides to the river—he’d watched an entire forest go up in flames.

The sump trees—desert date palms—were split by flames surrounded by yellow, red, and iridescent blue sparks that whirled around them like infernal flies. The African fan palms, crowned by smoldering fire, collapsed in on themselves, shackled to the earth by their massive roots. Beside the river, water-filled mangrove trees boiled before exploding in shreds of whistling flesh. Farther off toward the horizon, the fire hissed as it consumed the sap from acacias, cashew trees, ebony and eucalyptus trees while the creatures of the forest fled, wailing in terror. Muskrats, hares, gazelles, lizards, big cats, snakes of all sizes slid into the river’s dark flow, preferring the risk of drowning to the certainty of being burned alive. Their splashes distorted the reflection of the flames in the water. Ripples, little waves, then stillness.

Michel Adanson did not believe he’d heard the forest moan that night. But as he was consumed by an internal conflagration just as violent as the one that had illuminated his dugout on the river, he started to suspect that the burning trees must have screamed curses in a secret plant language, inaudible to men. He would have cried out, but no sound could escape his locked jaw.

The old man brooded. He wasn’t afraid of dying, but he regretted that his death would be of no use to science. In a final show of loyalty to his mind, his body, retreating before the great enemy, counted off its successive surrenders almost imperceptibly. Methodical even unto death, Michel Adanson lamented his powerlessness to describe in his notebooks the defeats of this final battle. Had he been able to speak, Aglaé could have acted as his secretary during his final agony. But it was too late to dictate the story of his own death.

He hoped desperately that Aglaé would discover his notebooks. Why hadn’t he simply left them to her in his will? He had no reason to fear his daughter’s judgment as though she were God. When you pass through the door to the next world, you cannot take your modesty with you.

On one of his last lucid days, he had understood that his research in botany, his herbaria, his collections of shells, his drawings would all disappear in his wake from the surface of the earth. Amid the eternal churn of generations of human beings crashing over one another like waves would come a man, or—why not?—a woman, another botanist who would unceremoniously bury him under the sands of his ancient science. So the essential thing was to figure in the memory of Aglaé as himself and not merely as some immaterial, ghostly scholar. This revelation had struck him on January 26, 1806: precisely six months, seven days, and nine hours before the beginning of his death.

That day, an hour before noon, he’d felt his femur break under the thick flesh of his thigh. A muffled crack, with no apparent cause, and he almost fell headfirst into the fireplace. Had it not been for Mr. and Mrs. Henry, who had caught him by the sleeve of his bathrobe, he might well have ended up with more bruises and perhaps some burns on his face. They laid him out on his bed and went to get help. And while the Henrys ran through the streets of Paris, he tried to press the heel of his left foot hard against the top of his right foot to extend his injured leg and allow the fractured bones in his femur to snap back into place. He fainted from the pain. When he woke, just before the arrival of the surgeon, Aglaé was on his mind.

He did not deserve his daughter’s admiration. Until then, his only goal in life had been that his “Universal Orb,” his masterpiece, should elevate him to the summit of the botanical world. The pursuit of glory, the jealous recognition of his peers, the respect of scientists all over Europe … all of this was mere vanity. He had used up his days and nights meticulously describing close to one hundred thousand “existences”—plants, shellfish, animals of all species—to the detriment of his own. Now, though, he was forced to admit that nothing on earth existed without human intelligence to give it meaning. He would give meaning to his own life by writing it down for Aglaé.

After the unwitting blow dealt to his soul nine months earlier by his friend Claude-François Le Joyand, regrets had begun to torment him. Until then, they had been no more than little sighs of remorse rising up like air bubbles from the bottom of a muddy pond, bursting here and there on the surface without warning, despite the traps his mind had set to contain them. But during his convalescence he had finally managed to master them, to fix them in words. As though divinely ordained, his memories had poured out in order onto the pages of his notebooks, strung together like the beads of a rosary.

Writing had brought him to tears—tears that Mr. and Mrs. Henry attributed to his thighbone. He had let them believe this, let them procure for him all the wine they could get their hands on, replacing the sugar water that he usually drank with a pint and a half of Chablis every day. But drunkenness was not enough to dim the pain of remembering, through the words he wrote in his notebooks, the intensity of his love for a young woman whose features he could barely recall. The contours of her face seemed to have been burned away in the hell of his forgetfulness. How could he translate into simple words the exaltation he had felt when he first saw her fifty years before? In writing about her, he had struggled to restore her to wholeness. And that had been his first battle against death. He had thought it a victory until death caught up with him again. By then, thankfully, he had finished writing his memoirs of Africa. Ripples, little waves of melancholy, and finally resurrection.

II

Aglaé watched her father die. By the light of a candle placed on his nightstand, a low cabinet with false drawers, he was withering before her eyes. There, in the middle of his deathbed, it seemed to her that only the tiniest fragment of her father remained. He was as thin and dried-up as kindling. In the frenzy of his death throes, his bony limbs gradually lifted up the surface of the sheets that held them down, as if each had its own independent life. Only his enormous head, reclining on a sweat-soaked pillow, emerged from the fabric in which his meager body seemed to be drowning.

This man who had once had long auburn hair, which he would tie in a ponytail with a black velvet ribbon whenever he dressed up to take her out of the convent and drive her to the Jardin du Roi on warm spring days, was now bald. The white down that glistened in the flickering dance of candlelight could not hide the thick blue veins that ran below the surface of the thin skin covering his skull.

Barely visible beneath his bushy gray brows, his blue eyes, sunk deep in their sockets, were glazing over. The fire in those eyes was going out, and, of all the markers of his decline, Aglaé found this the most unbearable. Her father’s eyes were his life. He had used them to examine the tiniest details of thousands of plants and animals, to tease out the secrets hidden within their sinuous veins, whether filled with sap or blood.

That power to penetrate the mysteries of life, which his eyes had gained from entire days spent scrutinizing specimens, was still palpable when their gaze was turned on Aglaé. His eyes probed her to her very depths, and her thoughts—even the most secret, the most microscopic of them—were seen. In such moments she was not merely one of God’s creations among many others, but became one of the essential links in the great universal chain. Used to scrutinizing the infinitesimal, his eyes suspended her against the boundless background of infinity as if she were a star fallen from the sky, put back in its precise place alongside billions of others, having thought itself lost forever.

Now drawn inward by suffering, her father’s gaze no longer had anything to tell her.

Indifferent to the acrid stench of his sweat, Aglaé leaned close to him as she would have done to an unexpectedly wilting flower. He tried to say something. From very close, she watched his lips move, deformed by the passage of a series of stammered syllables. He pursed his lips, then let a sort of wheeze escape from between them. At first she thought he was saying “Maman,” but in fact it was something like “Ma Aram” or “Maram.” He kept repeating it, over and over, until the end. Maram.

III

If there was one man Aglaé hated as much as she could have loved him, it was Claude-François Le Joyand. Three weeks after the death of Michel Adanson, he had published an obituary that was little more than a tissue of lies. How could this man, who claimed to be her father’s friend, have written that Adanson’s servants, the Henrys, had been the only people at his side during the final six months of his life?

As soon as the Henrys had told her that her father was dying, she had rushed to him from her estate in Bourbonnais. As for Claude-François Le Joyand, she had not seen him appear once during her father’s long decline. Nor had she seen him at his funeral. And yet this man had presumed to narrate Michel Adanson’s last days as if he himself had witnessed them. At first she wondered if the Henrys had been Le Joyand’s malicious informers. But then, remembering their silent tears, the sobs they had stifled so as not to disturb her in her grief, Aglaé had reproached herself for suspecting them of such vileness.

She had read the obituary only once, devouring its several pages, eager to find a graciousness that never appeared, drinking it down to its dregs. No, never could Le Joyand have found her father shivering with cold on a winter evening, crouched in front of the meager fire in his hearth, sitting on the floor and writing by the light of a few embers. No, she had not left her father in such penury that he would have been reduced to consuming nothing but milky coffee. No, Michel Adanson had not been alone when he faced death, as that man pretended: he had been with his daughter.

The purpose of that article, though she could not fathom the reason behind it, seemed to have been to burden her with public shame on top of her grief. It was impossible to refute the insinuations of a supposed friend of her father’s. She would probably never have an opportunity to hold him accountable for his spitefulness. Perhaps it was better that way.

Her father’s last words on his deathbed had really been “Ma Aram” or “Maram,” and not that ludicrous little cliché that Le Joyand had put in his mouth with his abominable obituary: “Farewell—immortality is not of this world.”

IV

As a little girl, Aglaé had been almost perfectly happy on those days, once a month, when her father would drive her in a carriage to the Jardin du Roi. There, he would show her the life of plants. He had counted fifty-eight families of flowers, but, when seen through a microscope, none of them resembled their own family members. His predilection for the oddities of nature, so prone to infringing its own laws beneath an apparent uniformity, had gotten the better of him. Often, early in the morning, the two of them would walk the paths inside the giant greenhouses, pocket watch in hand, marveling at the unvarying hour when the hibiscus flowers, irrespective of their variety, would open their corollas to the light of day. Since then, thanks to him, she had learned the art of bending over a flower for days on end, studying its mysteries.

The intimacy that had blossomed between them at the end of his life made Aglaé regret even more bitterly that she had never truly known Michel Adanson. When she came to visit him, on rue de la Victoire, before his broken femur, before his fall, she had invariably found him squatting, knees touching his chin, fingers in the black earth of a greenhouse he’d had built at the bottom of his small garden. He welcomed her always with the same words, as if trying to transform them into a legend: the reason he squatted like that rather than sit in a chair was that he had gotten used to the position during the five years of his trip to Senegal. She ought to try this resting position, he would tell her, even if it might not appear very elegant. And he would repeat this in the way of very elderly people who cling to their oldest memories, no doubt amused to see flickering in her eyes the same imaginings she had had as a little girl, on the rare occasions when he had told her bits and pieces about his voyage to Africa.

Aglaé was always surprised by the way the images conjured by her father’s words seemed to shift shape in her mind. Sometimes she imagined him as a younger man, lying in a cradle of warm sand, surrounded by Africans resting, like him, in the shade of the tall kapok trees. Other times she saw him encircled by the same people in multicolored costumes, taking refuge with them inside the immense trunk of a baobab, sheltering from the African heat.

This flux of imagined memories, summoned by words like “sand,” “kapok tree,” “Senegal River,” and “baobab,” had for a moment brought them closer. But for Aglaé, that had not been enough to make up for the time they had wasted avoiding each other—he, because he did not have a minute to spare for his daughter; she, in retaliation for what she had perceived as a lack of love.

When, aged sixteen, she had gone with her mother to stay in England, Michel Adanson had not written her a single letter. He had not had time; like so many others in the age of encyclopedias and philosophes, he had chained himself to his work. But while Diderot and d’Alembert—and, later, Panckoucke—had each been supported by a hundred or so collaborators, her father had not allowed a single other person to write any of the thousands of articles in his magnum opus. And he had started to forget the time when he still believed it possible to untangle the threads, hidden in the vast skein of the world, which supposedly linked all beings through secret networks of kinship.

The year he got married, he had begun to calculate the head-spinning amount of time it would take to complete his universal encyclopedia. If he assumed, optimistically, that he would die at seventy-five, that gave him thirty-three years. Working an average of fifteen hours a day, that made 180,675 hours of useful time remaining. From that moment on, he had lived as if each minute of attention granted to his wife and his daughter was tearing him away from a labor of love that they were preventing from reaching fruition.

So Aglaé had sought out another father—and found him in Girard de Busson, her mother’s lover. If nature had been able to fuse Girard de Busson and Michel Adanson into a single man, this human graft would, in her eyes, have come close to perfection.

No doubt her mother had thought the same thing. It was she, Jeanne Bénard, far younger than Michel Adanson, who had wished to separate from him, despite still being in love. Her husband had willingly acknowledged, before a notary, that it was impossible for him to devote time to his family. Those sincere, if cruel, words had caused Jeanne such pain that she had reported them to her nine-year-old daughter. And when, while still a young girl, Aglaé had discovered that one of her father’s books was entitled Familiesof Plants, she had remarked to herself that those plants were in truth his only family.

Where Michel Adanson was short and thin, Antoine Girard de Busson was tall and strong. Where the former could suddenly become taciturn and disagreeable in company, the latter—whom Aglaé called “Monsieur” in the privacy of the mansion to which he welcomed them, she and her mother, after her parents’ divorce—was cheerful and sociable.

A connoisseur of the human soul, Girard de Busson had made no attempt to supplant the girl’s father in her affections. In fact, he had even continued to help Michel Adanson in his mythical publishing project, ignoring the misanthropic scientist’s often rather rude rejections.

Unlike Michel Adanson, who never seemed to care much about Aglaé’s eventual marriages or his own grandchildren, Girard de Busson did everything he could to make her happy. He it was who provided her with the dowry she brought to her two unfortunate husbands, and, most significantly of all, it was he who bought for her the Château de Balaine in 1798. But, as though confusing her resentment for her father with her feelings toward him, she sometimes treated him harshly. For his part, Girard de Busson, who had no children of his own, patiently tolerated her abuse, even appearing happy that she should treat him so badly, as if seeing in her fits of rage the evidence of filial love.

Attempting to use her daughter’s marriage to expunge the dishonor brought down on her by her divorce, Aglaé’s mother had insisted that she marry, at the tender age of seventeen, a conventional military man named Joseph de Lespinasse, who, on their wedding night, unwisely decided to attack her virginity manumilitari. When the two of them were alone together in their bedchamber, this man dared to do the unforgivable. Assuming she was gripped by the same desire, he whispered to her, in a voice made hoarse by lust, that he wanted to possess her more ferarum, like a wild animal. This crude intimation in Church Latin had sickened her less than the brutal way he had attempted to give rein to his passion. In the end, she defended her body at the expense of his. Joseph de Lespinasse, a notorious carouser, had not been able to leave the house for a week afterward due to the purplish bruise that ornamented the periphery of his right eye. Barely a month later, she had obtained a divorce from him without difficulty.

Aglaé had been no more happy with Jean-Baptiste Doumet, a sublieutenant in a cavalry regiment who became a merchant in Sète. Her second husband’s only merit was to have given her two sons while strictly respecting the rules of procreativity without passion. If he had any peculiar tastes when it came to the bedroom, he did not practice them on her. Perhaps he reserved them for the women of those one-night stands, which, not long after their wedding, he made no attempt to conceal from her.

She feared she would never be happy. The idea that happiness in love existed only in books saddened her. And, even though she had experienced enough of life to put such sentimental illusions behind her, she could not help hoping, even after two failed marriages, that one day she would find the love of her life at first sight. Her faith in Love made her angry with herself. She was like one of those atheists who fear they will succumb to the temptation to believe in God on the day of their death. She cursed Eros without ever being able to renounce him completely.

So when Girard de Busson, seeing her in this melancholic state, told her he had bought the Château de Balaine and that she could visit it a month later, she felt herself come back to life. Before even seeing it, she decided that the château would be her refuge. People, plants, and animals—all would live there together in harmony. Balaine would be her private masterpiece, a work known only to Aglaé herself. She alone would be able to tabulate, once the project had come to fruition, everything that it had cost her. At Balaine, she would cherish even her disappointments.

V

Located not far from the town of Moulins, in the Marches du Bourbonnais, the Château de Balaine adjoined the small village of Villeneuve-sur-Allier, with its population of just under seven hundred souls. The first time Girard de Busson took her there, it was just the two of them. Jean-Baptiste, her second husband, had been thrilled to find himself alone in Paris and had not wished to accompany her, while Émile, their elder son, was still too young for such a journey and had been left in the care of his grandmother Jeanne.

Ensconced inside Girard de Busson’s luxurious carriage, drawn by four horses driven, as always, by Jacques, the family coachman, they left the house at dawn on June 17, 1798. Girard de Busson’s mansion was on rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré, close to the Folie Beaujon. They crossed the Seine by the Pont de la Concorde, but, after passing through Saint-Germain, Jacques chose to head south and then east, riding alongside the old city wall, from gate to gate. He wished to avoid the popular quarters of Saint-Michel, Saint-Jacques, and, above all, Saint-Marcel, from where they could also have reached the Barrière d’Italie via rue Mouffetard. Girard de Busson’s carriage was a clear sign of his wealth. And, this being the era of the Directoire, the working classes, still nostalgic for the glory days of the Revolution, were easily enraged.

Beyond the Barrière d’Italie lay the king’s road, renamed in the time of Napoleon the “Imperial Road no. 8,” which connected Paris to Lyon. Aglaé had rarely left Paris by the Route du Bourbonnais. Farther on, they stopped in Nemours, where fashionable Parisians liked to spend warm spring Sundays parading in open-top carriages.

Her eyes were half-closed as they began the long journey toward the Château de Balaine, her thoughts turned inward. She sat with her back to the direction of travel—facing Girard de Busson, who silently respected her feigned drowsiness—and paid no attention to the landscape moving slowly past the windows, letting herself be soothed by the gentle swaying. Little by little, in the half light of dawn, she began to imagine that the carriage’s creaking springs, mingled with the muffled clop-clop of the horses’ hooves, were the creak of the rigging and the whistle of wind in the sails of a ship anchored at the distant edges of the Atlantic. Then, suddenly, the brightness that had filled the interior of the carriage through the eastern window disappeared, as if, reversing the usual passage of time, night had followed dawn. A wave of murky light fell over them, swallowing her in a half sleep conducive to waking dreams. They had just passed the Carrefour de l’Obélisque and were now sinking softly into the Forêt de Fontainebleau.

She was standing on the bridge of a ship winged with white sails. Beneath her feet, the wooden boards radiated heat. Above her stretched a dusk of blue, orange, and green clouds, melting into a vaporous golden sky. Clouds of flying fish pursued by invisible predators splashed the boat’s hull. Their fins could not propel them fast enough to escape the danger menacing them under the water’s surface. Soaring toward the sky, they fled the wide-open pink mouths that surged upward from the ocean’s depths. But they were also being hunted from above by white birds: cormorants or seagulls, perhaps. And those silver-flashing arrows—half fish, half bird—were snatched by sharp beaks and crushed by powerful jaws amid bouquets of foam.

With her eyes still closed, feeling as desperate as those strange fish that were at home neither in water nor in air, she fought back her tears.

Later, this was all that Aglaé would remember of that first journey to the Château de Balaine in June 1798: her sad half-conscious dream, from which she thought she could wake whenever she wished. But the dream had pursued her all the way to their destination. It was only during the many, often solitary journeys that she undertook during the years prior to September 4, 1804—when she moved into a farmhouse near to the Château de Balaine while it was refurbished—that she began to associate her memories with the small towns and villages they passed through between Paris and Villeneuve-sur-Allier.

Montargis in the rain. The black waters of the Canal de Briare. Cosne-Cours-sur-Loire, where she stopped more than once to buy Sancerre wine for her stepfather and her father. Maltaverne, where a surprise storm kept her prisoner in its gloomy inn, the misleadingly named Au Paradis. Chancing to leave La Charité-sur-Loire one morning, she was given the most beautiful view of the river she had ever seen: drowning in mist, the Loire reminded her of the ghostly Thames, which she had looked out on during the year she had spent in London, before her first marriage. In Nevers she bought most of the château’s blue and white earthenware crockery. Of the other places she had passed, she recalled nothing.

Girard de Busson had timed their first arrival in Villeneuvesur-Allier to coincide with the festival of John the Baptist. Just before their entrance into the town, he explained to her that in almost all the villages of Bourbonnais, from dawn on that feast day, they would find—perched on makeshift stages in the middle of markets—peasant men and women hoping to be hired as farmhands or as servants in the houses of the local bourgeoisie. Dressed in their Sunday best, a bouquet of wildflowers tied to their waists, they would sell their labor to the highest bidder for a period of one year. After fierce negotiations over their salary, their new boss would give them a five-franc coin, the “denierdeDieu,” in exchange for their bouquet. Any peasant not wearing flowers was no longer for sale. Around noon, while the market gardeners and the farmers folded up their stalls following the end of this strange trade in flowers and labor, there would be a huge commotion as the local young people danced wildly in the streets. It was at this point that Aglaé and Girard de Busson’s carriage arrived in the village square.

Like gods appearing suddenly from the heavens, they had been the recipients of most of the bouquets that had changed hands that morning, and which a few laughing villagers threw onto the roof of their carriage. And so, pursued for a while by a small band of happy locals, and sowing wildflowers in their wake as the carriage shook its way down the winding path, they discovered the Château de Balaine at the end of a driveway lined with mulberry trees.

Aglaé did not immediately rush into the arms of her new home. She was content to observe it all, detached enough to collect impressions of the château that she would later associate with positive or negative feelings. She did not fully enter into the experience of her first encounter with Balaine, because she wanted to be able to relive it more easily later, alone with herself. The château had corner turrets on each side of a courtyard in the shape of a capital U: once wide-open to visitors, it was now overgrown with weeds. The windows of the turrets were surrounded by red and white stones, although their colors were now indistinguishable, covered with a tangle of ivy and moss. The façade was rendered ugly by an oversized passageway that ran from one side to the other.

Girard de Busson reeled off the names of some of Balaine’s owners since the fourteenth century. The first ones, the Pierreponts, had built it as a fortified castle, then passed it down from generation to generation for almost four hundred years. After 1700, when the Pierrepont lineage ended, there had been a succession of owners until a certain knight from Chabre, who had undertaken a complete reconstruction of the château in 1783 under the direction of Évezard, an architect from Moulins. Intimidated by the sheer scale of the work, the knight had changed his mind and sold it again.

Girard de Busson tried in vain to open the château’s front door. A smell of damp plaster and rotting wood escaped through a small crack. They did not manage to get into the entrance hall, but the shutters of the large windows at the back of the building had come loose and they could see beams of sunlight staining the blackish wooden floorboards, covered with a thick layer of dust.

“I’ve rented a farm close by where you could stay to oversee the renovation work,” her stepfather told her, nodding. “We’ll spend the night there tonight. But let’s walk around the house first.”

When they turned around, the few villagers who had followed them there had disappeared. Jacques was busy decorating the horses’ harnesses with the bouquets of flowers that had not fallen from the roof while they were driving. To the left of the building, Aglaé and her stepfather walked around a muddy pond, presumably replenished by a small stream nearby. The back of the building was even more overgrown and dilapidated than the façade.

It was then, in that moment, that she was finally aware of a feeling of deep joy rising within her. Thanks to a gift for optimism inherited from her mother, she was able to see beyond the apparent ugliness of an object, or a place, to its potential for beauty. If the faintest hint of vanished splendor had been visible at the back of the building, calling out to her to resurrect its long-lost luster, Aglaé would have ignored it. What she wanted was to be a pioneer, to remake the château according to her own idea of beauty rather than re-create past glories. She could easily imagine the last, debt-ridden Pierrepont, a hundred years earlier, petrified into inaction by the idea of committing the sacrilege of adding even the smallest of modern touches to this old château. Never would she put her descendants in the position of that last Pierrepont, a slave to stone ruins.

No, she would bequeath to her children a place whose living center would be not the château but its grounds, the beauty and rarity of its plants, its flowers, and all the trees that she would plant there. When buildings collapse after four centuries because the men who built them and their descendants’ descendants have all died out, it is the trees they planted that survive the onslaught of time. Nature never goes out of fashion, she thought with a smile.

Girard de Busson was secretly watching her, and he rejoiced at the sight of that smile. It was a new way of thanking him, more convincing perhaps than the words of gratitude she had repeated to him but which failed to fully describe for him the fullness of her joy and appreciation.

All the way back to Paris, she told Girard de Busson about her vision for the château’s grounds. At the time, they were restricted to a thin strip of land that would have to be enlarged through the purchase of neighboring properties. She would plant American sequoias there, maple trees, southern magnolias. She would construct a greenhouse to cultivate exotic flowers, shoeblack plants with their five large petals. Her father, Michel Adanson, would use his botanical connections to help her bring plants there from all over the world. And Girard de Busson said yes to all of this, in spite of the expense.

That evening, enthused by her first visit to Balaine, Aglaé deluded herself into believing she could interest Jean-Baptiste in her dream by giving herself to him. She wished she could find the words to evoke the eternal happiness that awaited them there, which would win him over as if by magic. But what she ended up saying to him left her disgusted with herself:

“You know where it comes from, the name Balaine? … You can’t guess? … Well, it’s because the people of the village have always gone there, to the land around the château, to collect bulrushes to make brooms—balais.”

“Hence the château’s pretty name!” Jean-Baptiste instantly replied. “At least it should be clean then … with two crossed brooms for a coat of arms!”

Aglaé was mortified less by Jean-Baptiste’s mockery than by the burst of naïve confidence that had led her to forget that her husband was not her friend. But, as if a part of her absolutely had to enter into communion with someone, as if the upheaval in her life was simply bound to touch the person who shared that life, she gave herself to him anyway. Powerless to stop herself seeking out his complicity, she was forced to watch, as if from outside her own body, as she deployed all her charms to mimic a tenderness she never would have believed herself capable of with him.

So, it was probably that very night, after visiting the Château de Balaine for the first time, that she conceived her second son, Anacharsis—and, in the same instant, her plan to divorce Jean-Baptiste Doumet.

VI

There had not been a day, since her first encounter with the Château de Balaine, when she did not dream about her property as if it were a lover. In a sketchbook she traced driveways, detailed flower beds, and designed forests in thick pencil strokes. She told her father about her plans, and Michel Adanson wrote to inform her that he was going to give up his research work for a half day every week so that she could visit him. And so she went to his house on rue de la Victoire almost every Friday, for a “postprandial get-together,” as he wrote to her on the invitation in his somewhat old-fashioned French.

Michel Adanson was not the man his fellow Académie members described after his death. It was the great and self-important Lamarck who fostered her father’s reputation as a truculent misanthrope. Aglaé imagined that men like her father, who placed honesty and justice above all other considerations and were incapable of compromising their principles even for the sake of their friends, were not well liked. Charm and politeness were not Michel Adanson’s strong points: he simply liked someone or he didn’t; there was no middle ground. He rarely tried to hide the disgust he felt in the presence of a colleague he did not respect. But over time, and thanks to the wisdom gleaned from Montaigne, whom he advised his daughter to read as well, he learned not to brood for weeks on end whenever someone uttered a word against him.

Her father had welcomed into his greenhouse three green frogs, which he would observe from the corner of his eye while repotting exotic trees for his daughter and the park she was creating at the Château de Balaine. The three of them were almost tame: they would let him approach without fear, and he even called them his “civilized gentlemen.” Aglaé did not understand this odd expression until she heard her father address one of those three amphibians with the words: “Monsieur Guettard, behave yourself!” Guettard had been one of Michel Adanson’s worst enemies during his final years at the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris. Seeing her smile, he said with a sparkle of mischief in his eyes that she had never noticed before: “That one isn’t venomous like his cousins from the Amazon in French Guiana, but I can assure you that the man whose name he bears did everything he possibly could to poison my life.”