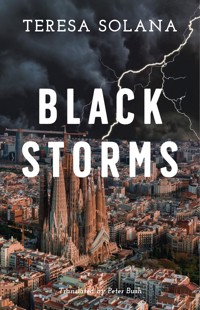

Black Storms

Teresa Solana

Translated by Peter Bush

Corylus Books

Copyright © 2024 Corylus Books Ltd

Black Storms is first published in English the United Kingdom in 2024 by Corylus Books Ltd, and was originally published in Catalan as Negres tempestes in 2010 by La Magrana.Copyright © Teresa Solana, 2010Translation copyright © Peter Bush, 2024Teresea Solana has asserted her moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.All characters and events portrayed in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or not, is purely coincidental.The publication of this work has been supported with a grant from the Institute Ramon Llull

For Clàudia, Ruth and Tom

Give sorrow words. The grief that does not speakWhispers the o’erfraught heart and bids it break. William Shakespeare, Macbeth, Act 4 Scene 3.Black storms shake the airDark clouds blind usA las barricadasAnarchist anthem from the Spanish Civil War, based on the Polish La Warszawianka, the Varsovian.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

Epilogue

Acknowledgement

About The Author

1

The man who was about to commit murder left home at six-thirty, after telling his girlfriend Mary he’d business to see to and checking his car keys were in his pocket. He’d not driven his third-hand Seat Ibiza for days. Its shabby appearance was protection against petty thieves even in a street like theirs where he usually parked it. Nonetheless, when he saw the thick layer of dust and the obscenities a finger had scrawled on the bonnet, sides and windows, he decided a filthy car would attract attention and it might be worth his while to shell out on a wash. The queue he found at the garage started to wear his patience thin. However, he cooled down after taking a glance at his watch: the professor had given him an appointment for eight forty-five and there was no point being early. He had more than enough time. No need to worry.

He drove his gleaming Seat up the Gran Via towards the Plaça d’Espanya, and then turned down Entença on his way to Roma. As soon as he reached the Plaça dels Països Catalans, he left the car in a parking lot and went into Sants station, all set on melting into the crowd. He was sure nobody would notice him in that chaotic, crowded spot—that’s why he’d chosen it—and hurried into the lavatories gripping his black backpack. It contained all he needed to carry out his plan of action: a disguise, latex gloves so he didn’t leave fingerprints, and a length of plastic-covered clothesline. It was an old, light backpack, nothing too flashy to attract thieves on the lookout for easy pickings from commuters and tourists.

He found an empty stall in the gents, checked the catch was working and rather nervously shut himself inside. He took a wrap from his pocket, prepared a line of coke and racked his brain wondering how he’d eke out his meagre supplies until Mary brought a fresh consignment. The cocaine revitalised him, and with the drug still buzzing in his brain, he took off his shirt and jacket and donned the disguise he’d crammed into his backpack. All he needed from now on was inside a corduroy bag he slung over his shoulder that radically transformed his appearance when it was combined with the jeans, the shirt with the Mao collar that was a couple of sizes too big, and a Palestinian scarf he’d bought at the same hippy stall where he’d found the shirt. Just in case, a khaki cap and fake Ray-Bans hid his eyes, hair and part of his face. When he emerged from the lavatories and glanced at the queue at the ticket counter, he could only smile. Nobody would ever recognize him in that jazzy disguise.

He went to the left-luggage office and deposited the backpack in a locker before catching the Line 3 metro. Twenty minutes later the man who was about to commit murder was walking along La Rambla on his way to the history department. While he progressed steadily, trying to dodge the bustling pedestrians and bedazzled tourists in his way, he felt altogether pleased with himself and his brainwave pseudonym and doctoral-student status. Had the professor smelled a rat, he might have caught him out and told someone, even informed the police, but his ploy had worked a treat. The professor had swallowed the lot and agreed to see him in his office in the evening, after classes, when the corridors of the department would have shed their daytime throng of students and professors, and he could avoid dozens of potential witnesses eyeing his every move. If everything went to plan, terminating the professor’s life would be simple enough. So far, the man about to commit murder had calculated right. But only so far.

When he had rung him mid-morning the previous day, he was surprised by how accommodating the professor proved to be. Something he hadn’t anticipated. He’d expected to hear a self-satisfied, smug academic at the other end of the line, but quite against all odds the latter immediately agreed to see him at an untimely hour the following evening and asked for no further explanations. Before phoning he’d prepared a little spiel, convinced he’d have to produce good reasons to insist on that urgent, late appointment with the professor outside teaching hours. As a last resort, he’d invented a sad tale about a car accident or a mother in hospital, but finally he hadn’t needed to invoke any such tearjerker. The professor had been very pleasant from the start and agreed straightaway; it never struck him that the time or urgency to meet was at all out of the ordinary. He’d kindly told him where his office was and apologised for only being able to offer him a half-hour slot at the very most.

‘It’s All Saints Eve and I must be home by nine-thirty because we have invited people over,’ he’d said on the other end of the line.

The professor had returned to the department only three weeks ago and was feeling rather happy. He’d not crossed the university threshold for six months, and now sensed that his ability to re-engage with the tediously placid pace of academic life was a sign that everything was indeed returning to normal. His long convalescence had sorely tested his mental stamina, particularly at the beginning when he’d been forced to give up reading because the medication meant his eyes kept wandering and he lost his thread. The setbacks occasioned by cancer were compounded by the dismal threat of retirement that preyed on his every moment like an unjust life sentence he’d soon have to accept as inevitable. In a couple of years when he reached seventy, the university would organise an emotional homage, pat him on the back and declare him unfit to teach. It would dispatch him coldly back to his home and he, the dedicated professor, would be forced to bid farewell to his students, because that was the will of an administration that ignored intellectual ability, merit or personal factors. Although he’d grasped the nettle, trying to acquiesce benignly to the idea of the changes he’d face when the moment came to give up his chair to his successor, the ageing professor struggled to imagine a life far from the halls of knowledge, the routine of classes, the invigorating banter of students and never-ending disputes in departmental meetings. He’d surely have more time to write when he retired, his wife and children piously argued. Despite that welcome prospect, the professor was clear-sighted enough to realise that retirement amounted to concluding another chapter in his life at a time when there were few pages left to turn.

His illness had involved giving up sex, and incipient diabetes had long since banished fat, sugar and alcohol from his diet. Gone were the days when he could head all alone to the countryside at the weekend on the pretext that he was going to pick mushrooms because mobiles couldn’t reach the places where he liked to go, even though it meant making his wife and children suffer. As he wasn’t as strong or agile as he used to be, he could no longer swim out to the open sea in the summer or clamber over rocks with his grandchildren to collect mussels when they went to the beach. However, as he’d never been that excited by sex or desired to excel at sport, growing old and abandoning those activities had always been a secondary preoccupation: that wasn’t what he found depressing. He’d become resigned to ageing. Conversely, the prospect of being forced to stay cooped up at home like a redundant item of furniture, as if the mere fact of hitting seventy meant one had to wind down like a clockwork toy, was intolerable. True enough his body was failing him, but his grey matter had matured like vintage wine and that was something to be proud of. He could still boast a prodigious memory that was the envy of his younger colleagues, and the very same years that had wasted his flesh had transformed the erudition he’d patiently accumulated into a solid store of wisdom. Cancer had made life difficult over the last year and a half, but his inopportune sickness had at least left the good health of his neurones intact. Stoic in outlook, the professor was happy to harbour a lucid mind in a shipwreck of a body.

His wife had started grumbling the second he informed her at lunchtime that he’d agreed to see a doctoral student at the end of the day. To avoid a row, he’d promised to take a taxi as soon as he left the department rather than meandering leisurely back, as he preferred. He’d be home by half past nine at the latest. In the give and take over dessert, she’d persuaded him to take his mackintosh and scarf, arguing that the television weatherman had predicted a cooler night. As he sat in his office and watched the black clouds now gathering and threatening to release a deluge, the professor was pleased he’d listened to her. Even though October had been extremely hot and the citizens of Barcelona were still in short sleeves, his wife was right. The weather was changing and, when he left the university in the evening, autumn would very likely make its presence felt with a display of gusting wind and rain. He was still convalescing, and it was better to err on the side of caution than risk catching a dangerous chill.

‘Professor Parellada?’

The man who was about to commit murder knew the academic was in his office, and he opened and closed the door quietly behind him without waiting for his reply. He was relieved to find a frail little man who looked older than he’d expected and thought this was going to make his task much easier. The professor’s jacket and shirt hung on him as if he’d shrunk, and he glimpsed the highly respected scholar’s atrophied muscles under his dark, conventional suit, the fruit of half a century of deskbound existence, peering at books and shuffling papers. At a glance, the man who was about to commit murder calculated that slight body could barely weigh in at sixty kilos, and, when he saw the professor’s sluggish movements and emaciated, pallid face, he deduced he must have fallen foul of an illness that was implacably wasting his body. He grinned as he realised that would also facilitate his task. Luck seemed to be on his side.

The professor got up from his chair, and slowly walked towards him, smiling broadly and holding out a hand. It all happened very quickly. The stranger simply had to wait for the tiny man, sapped by his last round of chemotherapy, to trustingly turn his back and he would slip the cord around his neck and stifle any cry he might try to utter. He’d seen it done in a film and felt it was a simple, effective, and above all clean procedure. He couldn’t risk blood splattering his clothes, as happened the previous time; nor could he take any chances on the professor screaming and being heard, even though the department was almost deserted on the eve of a holiday. The best option, he’d calculated, was to strangle him from behind, taking the professor by surprise before he realised what was happening. After all, he was experienced now and murder wasn’t the big deal he’d initially thought it would be.

The old man barely offered any resistance and his frail body stopped convulsing after a few seconds, eight, maybe ten. As a precaution, he tightened the cord for longer than was necessary and counted silently and unhurriedly to sixty, determined to carry out his plan to the letter. He might as well do it properly. After that minute, one of the longest he’d ever lived, he gradually let go and the professor collapsed like a puppet, all limp in that old-fashioned, oversized suit. It had been a silent, quick and extremely clean operation. Not a speck of blood anywhere.

He immediately found the packet he’d come for on the desk. It was a brown business envelope he stuffed inside the corduroy bag along with the piece of cord he’d used to strangle the professor. After listening to make sure nobody was in the corridor, he switched out the light, put his cap back on and stood in the dark holding his breath. He had to be careful, because a few students were still lingering in the building with folders of notes tucked under their arms, and the cleaners had started work and were opening and shutting doors, emptying wastepaper baskets and vacuuming. If he didn’t want to be caught, he shouldn’t waste time. He should get out of the building fast.

He was about to open the office door when he noted an unpleasant smell in the air, one he didn’t remember being there when he walked in. It was an acrid stench he immediately identified, one that transported him to the sordid nursing home where he’d parked his mother for the last ten years. The professor had pissed himself and his urine stank of old age and the medicines he had been taking to fight the disease that had been exacting such a toll. As he glanced at the body on the ground, a pathetic scrap of flesh, supine in its own secretions, the man who had just committed a murder thought he had perhaps done him a favour.

He nudged the door open, took the gloves off and left the office. He walked past some students in the lobby but, since he was sure nobody would recognize him with his fake Ray-Bans and young leftist garb, he strode by them unfazed by the curious looks coming his way. However messy this business became, he reflected, who would ever dream of connecting him with the murder of an old professor?

‘Hey, ’scuse me! You got a light?’

He’d just stepped out into the street and lit a cigarette with hands that were still shaking when two twenty-year-olds, their cleavages hidden behind folders emblazoned with the university logo, suddenly stopped and blocked his path. His heart missed a beat, because the man who had just committed a murder hadn’t anticipated that two brazen students might accost him with unlit cigarettes. As he swerved to avoid them, he unintentionally knocked into one. He continued walking as if nothing had happened, didn’t even turn round to apologise, and the girl he’d accidentally shoved out of his way screamed a ‘Fucking bastard’ after him that echoed down the street. The man who had just committed murder hurried in the direction of La Rambla in his search for urban anonymity. When he’d finally disappeared into the stream of people bustling there, he took a deep breath and told himself it was a totally trivial incident. However messy things got, as soon as he got rid of his disguise and recovered his usual look, no one would ever recognise him, let alone identify him. His plan had worked to perfection. He shouldn’t give it another thought.

The professor’s wife had been right: it had cooled down and an icy, cutting wind was gusting down the streets making everyone rush along. He regretted he hadn’t chosen thicker clothes. Luckily it hadn’t started to rain, even though the clouds scudding over the tops of buildings were soot-black and the air smelled as if a storm might break any minute. The man who had just committed murder went into the Plaça de Catalunya metro and down to the platform. When the train came, he sat in the corner of a compartment and looked at the floor. At that time of night, apart from a few youths going out on the town, sporting their respective urban tribal uniforms or imported Halloween garb, disguised in wigs and scary masks on their way to a disco, the rest of the passengers were too exhausted to notice a dozing student gripping a bag in which he was no doubt carrying his lecture notes. But he wasn’t asleep. A tiny voice was echoing around his head in a deathly cadence of litanies and spells: everything had worked out just fine.

2

Norma had been looking at her watch for some time while trying to join in the conversation and prove she wasn’t nervous. She didn’t want to make a drama out of something she knew was no such thing, and above all wanted to avoid her family spending supper consoling her or, worst of all, making her feel even more agitated with their pessimistic speculation and impractical advice. As they were familiar with Norma and her moods, they’d been keeping calm and biting their lips for over an hour, but she’d only have to give them the slightest excuse to start lamenting for that festive occasion to turn into a psychodrama where everyone would stick their oar in. Norma worried about her daughter, of course she did, but she preferred not to show it in front of her family. Her husband Octavi was in complete agreement.

Her colleagues had assured her that it was a matter of time, a few months, a couple of years at the most. ‘These blasted young people and their idealism!’ Chief Superintendent Nebot had commented sympathetically when he heard the news. He had even concurred that it wasn’t such a big deal and tried to soft-pedal the subject. He’d had teenage children and knew from experience that this kind of rebelliousness was an adolescent thing. Naturally, his children had never gone so far, the chief inspector had added, with a smile of relief on his lips, but in any case, they’d be on the alert. They’d keep a watchful eye on the girl and keep Norma informed. Open confrontation, he’d declared in that half-authoritarian, half-affable tone he used towards his subordinates, would only make matters worse. Norma should be extremely patient and let time take its course.

Octavi had said almost as much. Octavi kept his anxieties to himself, and the calm way he approached those tensions helped ensure Norma didn’t go overboard. Violeta’s decision had taken everyone by surprise, although perhaps not that dramatically, because Violeta was a girl who was used to speaking her mind and everyone at home knew her strong opinions on certain subjects. But to do what she had done! Sure enough Guillem, Violeta’s biological father, had handled his daughter’s unexpected turn with equanimity, but, as he was Guillem, Norma reckoned, any consolation her ex might offer was of little use because he was always so accepting of his daughter’s ways. Octavi was rational and even-handed, but Guillem, in Norma’s view, was a dreamer and she could have no confidence in his judgements.

Norma had always thought, when it came to character, that her daughter and her biological father had little in common, but now she wasn’t so sure. Up to that point, Norma had always relied on clichés and put Guillem’s impulsive manner down to his homosexuality, making her ex’s rather outlandish ways a feature of the whole gay community. Clearly, perhaps his being gay was irrelevant, Norma now reflected when she thought about the adventure Violeta had embarked upon, but Guillem’s tendency to dream was a trait her daughter had inherited. After all, he was her father and they were bound to be similar in some respect, considering that physically she wasn’t like him at all. Violeta resembled her mother, everyone said so, and the pair of them, as Great-grandmother Senta was continually reminding them, were cut from the same cloth as Great-grandfather Jack.

As they owed her leave from time immemorial and they had no urgent cases on their hands, Norma had taken, most unusually, a whole day off. She’d got up early, cleaned and tidied the house, gone to the market, and done the cooking. You can’t improvise supper for ten people in half an hour, particularly when it’s a festive celebration. Norma hated cooking, but she defended the idea (an antiquated one, according to her girlfriends) that hospitality means making an effort to prepare a good meal when you have guests. Not that it happened very often, because with Octavi’s and her professions it was difficult to plan ahead, but maybe that was why Norma thought it was in bad taste to invite someone to dinner and offer them a pitiful pre-cooked meal or the usual pa amb tomàquet, as if tasty food wasn’t important. That All Saints Eve they were celebrating her birthday, and, before gorging on chestnuts, sweet potatoes, and the traditional panellets, Norma had decided her family would enjoy home-made mushroom soup and fresh sea bass cooked in the oven.

All Saints Eve is a peculiar time to come into the world. Deputy Inspector Norma Forester had done so thirty-eight years ago, around midnight, in a surprisingly short labour for a woman who was giving birth for the first time. Mimí, Norma’s mother, would recount how the following day the room in the clinic where she’d had Norma saw a toing and froing of bunches of chrysanthemums and people dressed in black. As All Saints Day is a holiday, everybody decided to take the opportunity to drop by the clinic on their way to the traditional visit to the cemetery, so that the cheerful baskets of flowers they brought Mimí were accompanied by mourning dress and other sadder bouquets for the deceased. Norma’s mother also recalled the blank expressions on the faces of relatives who couldn’t decide whether to fuss over the baby or console her, as they were unable to accept that Mimí had decided to bring that child into the world all alone, without a husband by her side. It was the year 1971, and, according to Mimí, despite the Bocaccio nightclub, the cosmopolitan veneer of the Gauche Divine and trips to Perpignan to see banned films, being a single mother was still considered shocking in a schizophrenic Barcelona suffering the final throes of Franco’s dictatorship. When she told that story all smiles, but with the hint of sadness in her voice of someone who’d long left behind her the best years of her life, Senta looked at her and nodded silently.

‘Maybe we should start. I don’t think she’s going to come…’ said Norma, looking at her watch and getting up from the sofa. ‘It’s gone half past ten.’

‘We’re in no rush, love. We can wait a while longer.’ In her way Mimí also felt anxious about her only granddaughter. ‘You could ring her, perhaps she’s on her way.’

‘Norma’s right.’ Octavi cut short any possible family wrangle over whether they should or shouldn’t wait for their daughter. ‘Let’s start on supper.’

He said it gently, but everyone stood up without arguing and took their places at table, while Norma and he headed off to the kitchen. Octavi never raised his voice, but, as is often the case with doctors, his voice possessed an imperious tone and natural authority that was difficult to challenge. Octavi wasn’t angry with his daughter, but he was much more worried than he seemed. After all, Violeta was only eighteen and, even though he’d never said as much to Norma as a matter of prudence, he too was worried by the reckless genes of that English great-grandfather that ran through his daughter’s DNA. Octavi was convinced that externalising his anxiety would change nothing, or would rather complicate matters, so he said nothing. He knew Violeta and trusted in her judgement, but most of all he trusted in the eighteen years of patient instruction during which he and Norma had made every effort to inculcate in that girl the only three things they considered vital in life: generosity of mind, a sense of justice and common sense. You had to expect at her age that she wouldn’t always keep her feet on the ground, thought Octavi. Violeta was an only child. As were Mimí and Norma.

Every year, on All Saints Day Eve, Norma organised that small family dinner party to celebrate her birthday. Together with the big party they organised for Violeta, whose birthday fell in May, and Christmas Day (Octavi’s birthday wasn’t a good date, because it fell in the middle of August), these were the only occasions when she and Octavi gathered their respective families around a table for dinner. Norma’s work didn’t respect timetables or holidays as they were always eager to point out, and they were quite right, because, more than once, with a fridge full of delicious food, Norma had been forced to call everyone at the last minute and postpone a lunch or dinner that had been planned weeks before. However, that evening, Norma had everything under control, or at least so she thought. As she’d officially not seen her daughter for a couple of months (in fact, she’d gone more than once to spy on her in the streets of Gràcia and see for herself that she was all right), Norma had succeeded in forcing her boss to promise that, whatever happened, they would forget her phone number that night and let her eat supper in peace with her family. Inspector Bernat Roca was Norma’s superior in the murder squad and Norma was convinced that something horrendous would have to happen for a man like the inspector to go back on his word.

For the first time since she’d been organising those suppers, Norma had decided to invite Guillem and his partner Robert to the party. This was the lure she’d thought of to ensure her daughter turned up at her traditional birthday supper, to which she’d also invited Octavi’s parents and Aunt Margarida who, being a nun in an enclosed order, had to contrive an excuse every thirty-first of October to leave her convent.

Norma’s mother and Great-grandmother Senta had lived with Norma and Octavi ever since Mimí had been widowed, and Norma was conscious that the absence of her stepfather had turned a birthday party into a rather melancholy celebration. That it fell on All Saints didn’t help, and even less so that Great-grandmother Senta spent her time lighting candles and distributing small bunches of flowers throughout the house in front of the yellowing photos of deceased relatives. Senta, despite her tiny stature and absent looks, was still sharp-witted at ninety plus, and Mimí, ever loyal to the hippy aesthetics of her youth, still wore her hair long and dyed orange, although she was sixty-nine.

As well as being Norma’s ex-boyfriend and Violeta’s biological father, Guillem was Octavi’s little brother, and that initially uncomfortable coincidence had in the end helped cement a closeness they had never enjoyed as boys because of the age gap. There were ten years between Octavi and Guillem and they weren’t at all alike, or, as Mimí liked to say, they were as alike as an egg and a chestnut. It was as if in each of the pregnancies the features of the two progenitors had remained separate in the womb without ever mingling, the outcome being that physically Guillem resembled his mother, and Octavi, his father. Guillem had inherited Isabel’s dark, curly hair and olive-toned, round-featured face, whereas Octavi had inherited his father’s athletic complexion, prematurely grey hair and his lively, short-sighted eyes. Anyone observing his angular face would be unable to deduce that Guillem and he were brothers, and any interaction with them only confirmed that impression: where Octavi used cold reason and logic, Guillem applied enthusiasm and intuition. Octavi was a man of science, disciplined, sensible and methodical, whilst Guillem, who from childhood had revealed an artistic bent that never blossomed, was more bohemian in attitude and a dilettante who quickly got bored with everything.

Guillem’s partners never lasted, though he’d been living with Robert for almost a year and Norma was sure it was working this time. Robert, who knew Violeta and Norma but not the rest of the family, couldn’t stop feeling on edge. He’d had other partners in his life and several times had experienced the unpleasantness of reticent fathers- and brothers-in-law, but it was the first time he’d had to dine with a forensic doctor and a female officer, and he really didn’t know how to approach it. He wasn’t overjoyed by the idea that Norma was a cop, and, being a sensitive soul, felt sick at the thought of Octavi carrying out autopsies. When he discovered his future brother-in-law worked at the Hospital Clinic de Barcelona and that he was head of the forensic pathology department, he immediately assumed he would be dealing with a sinister character out of one of those Gothic novels he collected in bibliophile editions, and took fright. What kind of person decided to devote his life to slicing up corpses, and earning his living from the nasty realities of death? A psychopath? A doctor unable to cope with the suffering of the living? Robert was horrified by the dead and couldn’t understand how someone would opt to spend their life dissecting corpses in a gloomy basement. Out of respect he’d said nothing to Guillem, but deep down he was certain there must be something sadistic or perverse in the character of individuals who, like Octavi, embraced such a grim profession. A susceptible fellow like him began having nightmares the moment he discovered he’d have to meet him and shake his icy hand. To make matters worse, they’d invited him round on a particularly lugubrious date like All Saints Eve, and, as he was polite and hadn’t dared turn down the invitation, he’d now have to sit down for dinner with that outlandish family and all the souls in limbo of the unfortunate folk Octavi had opened down the middle. Robert was at once highly impressionable and extremely superstitious, and he reckoned this was altogether a joke in bad taste.

However, the truth is that he felt rather annoyed when, after a few minutes of conversation, he was forced to admit that Dr Octavi Claramunt was not only not at all sinister but sensitive and attractive enough to arouse the interest of both sexes irrespective of his profession. Perhaps he did have the distant air of a learned professor, but Robert immediately realised that, as well as possessing a dangerously seductive myopic glance, his future brother-in-law was pleasantly extrovert with a wry sense of humour. Reluctantly, because all that macabre paraphernalia in his fantasies had come with a delicious thrill of Victorian decadence, Robert had to accept that his fear and loathing were completely unfounded.

Distant thunderclaps stirred the cat Hamlet from his nap, and he raised an ear and gave a huge yawn before dozing off again curled up on the sofa. Norma’s father-in-law, Maurici, began to speculate on the imminence of the storm, and the conversation immediately focused on the weather and the power of Senta as an oracle, as she had forecast rain hours before. Of late, Senta had taken to predicting the weather, thinking that this was a skill she’d magically acquired with old age. Since she mostly got it wrong, nobody took any notice of her except for Mimí. Nevertheless, the icy wind blowing that evening seemed to confirm her prediction, and now and then Senta looked at her family, nodding and smirking like an inspired seer. The long summer had finally decided to beat a retreat, taking with it the heat of a sun that was beginning to fade, and the smell of autumn, rough seas and dry leaves was in the air. Octavi had to quickly stand up and close a window after the wind blew it wide open and scattered sheets of paper around.

‘Are you alright?’ Guillem whispered anxiously to Robert. ‘You don’t look too good…’

‘No, I’m fine. I slept badly last night,’ Robert lied. ‘It must be the weather.’

Everybody could see that Robert was looking pale, but no one said anything. That evening before setting out, without saying a word to Guillem, Robert had taken a tranquiliser to help him survive the grotesque dinner party he’d been expecting, and now, after that pill and a couple of glasses of excellent Ribera del Duero had hit his empty stomach, his head was beginning to spin. Norma started ladling out the soup and Octavi was opening another bottle while Robert nibbled on a piece of bread hoping to bring himself round. He wasn’t feeling so on edge now, but his eyelids felt heavy and he was sleepy.

‘This soup smells divine,’ said Maurici, who had a soft spot for the young woman. ‘Norma, when you make your mind up, you’re a dab hand…’

‘Octavi helped me clean the mushrooms. Today we must share the praise!’ Norma replied, smiling and winking at her husband.

Robert tried the homemade soup with freshly picked penny buns, chanterelles and trumpets of death and was in awe, so he joined in Maurici’s praise. Rather shamefacedly, he reflected that before setting foot in that house he’d imagined his dandyish sophistication would lead to titters, that they’d make him drink cheap wine that would provoke acidity in his stomach and that he’d have to listen to jokes about poofters from the lips of a foul-mouthed female officer and pretend he found them amusing. But he’d got it totally wrong, because that supper wasn’t at all the surreal soirée he’d imagined. Norma and Octavi seemed quite civilised despite their professions, and even Isabel and Maurici, Guillem’s parents were polite enough to just smile and exchange knowing looks.

‘It can’t be at all easy to get used to handling the dead. I suppose you must see all kinds of things…’ Robert suddenly said, unable to restrain himself any longer.

Everybody sighed, and Norma, who in the fifteen years she’d been with Octavi had heard similar comments thousands of times, couldn’t stop smiling. Like the rest of the family, she was used to it. In fact, Robert had promised he’d not be so banal as to ask his brother-in-law anything about his profession, but the tranquilliser, glasses of wine and convivial atmosphere had led him to relax and his troubled subconscious to voice his thoughts out loud. He immediately regretted having done so and turned bright red. He stammered an apology.

‘I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have brought the subject up. It’s inexcusable. I mean…’

Octavi smiled and quietly rested his spoon on the rim of his soup dish. He drank a mouthful of water, straightened his glasses and adopted a professorial air. Everyone went quiet, very aware of what was coming next.

‘Please, not at the dinner-table,’ Mimí protested half-heartedly.

‘The transformations undergone by the body from the time of death are part of a completely natural process, the stages of which are extremely well-defined …’ Octavi began solemnly, ready to respond to Robert’s curiosity.

But the noise of keys opening the door interrupted the keynote lecture Dr Octavi Claramunt was about to impart for the benefit of his guest.

3

Antoni Falgueres was the man who had killed Professor Francesc Parellada; he was forty-nine and a lawyer. His was a third-rate legal mind, to the extent that the only clients he represented came from a prestigious practice that often had recourse to his services to ensure their name did not circulate in the courts in connection to certain subjects. For the last eight years Antoni Falgueres had only signed claims and statements written by others and acted as a frontman in complex operations designed to defraud the tax authorities via fake invoices, shell companies and tax havens. In exchange for lending his signature and administering a handful of companies created expressly to hide income and avoid taxes, the lawyers in the practice religiously paid him a wage on the side that was no great shakes but that allowed him to pay the rent on his tiny office on the Ronda de Sant Antoni, keep up appearances and make it to the end of the month. As there were thousands of failed lawyers like himself in Barcelona ready to sell their soul for a dish of lentils, he was in no position to negotiate. Antoni Falgueres had to accept the miserly crumbs they offered, paltry amounts given that he was such a key player. Now and then, depending on the degree of dodginess of the deals that required his signature, they’d give him a small bonus that he and Mary soon spent on paying off debts owed to local drug dealers and new ones they soon acquired.

However, the job that had led him to murder Professor Parellada had nothing to do with the swanky lawyers he worked for, and even Mary knew nothing about it. He wasn’t a professional killer, not even one of those thugs he sometimes had to hire to intimidate a witness or beat up someone, and he couldn’t stop feeling nervous. Up to that point, and apart from the unfortunate episode with the two students, he was sure everything had gone smoothly, but even so he was worried his inexperience might let him down and they’d end up catching him. He could get twenty years, he reflected, with a bit of luck that might be reduced to ten or fifteen, but that, at his age, with the damage inflicted by coke and alcohol, was the most he could expect before he kicked the bucket. He had wasted most of his life, and time was catching up on him. He couldn’t allow himself to make a mistake.

As soon as he arrived at Sants station, he went to the left-luggage office and retrieved his backpack. He went to the station lavatories, removed his disguise and recovered his anodyne appearance as a respectable citizen that served him so well to pass unnoticed. After that, he sniffed the remains of the coke still left in its wrap and, his confidence restored by the drug, he took scissors from the bag and cut the gloves and cord he’d used to strangle the professor into small pieces which he patiently flushed down the pan. He had to pull the chain ten times to avoid blocking it, and, once he was sure those compromising items were definitively lost in the city’s sewers, he left the station pretending not to be in a hurry and went to the parking lot to pick up his car.

He drove from Sants to Hospitalet to get rid of his disguise. When he reached La Florida market, he double-parked his car and took out of his backpack the three crumpled supermarket plastic bags he’d remembered to take when he left home. He put the scarf, cap and glasses inside, and, trying not to attract any attention, threw the bags into three different containers knowing that sooner or later they’d fall into the hands of the poor guys who spent their time looking for treasure among the rubbish. He still had to get rid of the shirt, but he’d had a rethink and decided to do that at home following the same procedure via which he’d dispatched the gloves and cord in the station lavatories. The corduroy bag, that now contained the envelope he’d taken from the professor’s desk, wasn’t a problem because he’d decided to wrap it in fancy paper and give it to his niece for her birthday, and, as far as his jeans and trainers went, they weren’t a worry, because they were part of his normal wardrobe and there were thousands like them in Barcelona. The cheap brand of trainers were ones he wore when he went out for a ride with Mary at the weekends before she started work, and the black jeans he wore were on the tight side and hardly his favourites, a present from Mary, and they could return to oblivion at the back of the wardrobe. Everything was under control.

When he was going back to his car, he saw it was about to rain and decided to hurry. His old Ibiza didn’t have a GPS, and the last thing he wanted was for the first storm of the season to catch him driving around a district and streets that were totally unfamiliar. Once inside the car, when the first drops started to fall, he switched on the radio and took some deep breaths. The days of poverty and making ends meet, of drinking the last drop in every bottle and suffering because local dealers wouldn’t give them more wraps of coke, were now a thing of the past.